Abstract

J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2012;14:144–148. ©2012 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is a subclinical marker of coronary artery disease and identifies asymptomatic individuals at high risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) events. The metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a constellation of clinical factors that increases the risk of developing diabetes and CVD. The authors’ objectives were to estimate the prevalence of MetS in patients with PAD and to determine the prevalence of PAD in the population of asymptomatic US adults 40 years and older with MetS. The authors analyzed data from 3 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES, 1999–2004). Prevalence of MetS as defined by the Third Report of the Adult Treatment Panel criteria and prevalence of associated cardiac risk factors were determined in 5376 asymptomatic participants 40 years and older. Presence of PAD was defined as ankle‐brachial index <0.9. Estimates were weighted with the sample weights accounting for the unequal selection probability of complex NHANES sampling and over sampling of selected population subgroups. Prevalence of PAD in asymptomatic US adults 40 years and older was 4.2%. PAD prevalence in persons with MetS was 7.0% compared with 3.3% in persons without MetS. A total of 38% of the population with PAD also had MetS. High rates of abdominal obesity, hypertension, hyperglycemia, and low high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol are significant contributors to both MetS and PAD. Persons with MetS have twice the risk of having PAD. Of persons with PAD, almost 40% have MetS. The presence of either PAD or MetS should warrant screening for both conditions so that risk stratification and management of risk factors may be performed.

The ankle‐brachial pressure index (ABI), the ratio of ankle to brachial systolic blood pressure (BP), is a simple noninvasive test that is used in the assessment of lower extremity arterial obstruction and for screening of patients with suspected peripheral arterial disease (PAD). An ABI <0.9 is diagnostic of PAD and is associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease, stroke and transient ischemic attack, and all‐cause mortality in both men and women. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 For these reasons, even asymptomatic patients with PAD should be treated with aggressive risk factor reduction. 6

The metabolic syndrome (MetS) is defined by the clustering of at least 3 of the following 5 interrelated metabolic factors: abdominal obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, low levels of high‐density lipoprotein (HDL), hyperglycemia, and hypertension. Patients with MetS have a 2‐ to 3‐fold increased risk of having an adverse cardiovascular event. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10

Because PAD and MetS are independently associated with a high incidence of future cardiovascular disease (CVD) events, identifying the respective prevalence of PAD in those patients with MetS and vice versa could identify a group of patients at especially high risk for further cardiovascular events. To this end, the purpose of this present study was to determine the prevalence of: (1) MetS in patients with PAD and (2) PAD in the population of asymptomatic US adults 40 years and older with MetS.

Methods

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is a nationally representative survey of the US civilian noninstitutionalized population conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Since 1999, NHANES has conducted continuous interviews and physical examinations. This study is based on 6 years of the continuous NHANES survey data (1999–2004).

NHANES participants are interviewed in their homes to obtain information on health history, health behaviors, and risk factors. Those participants then undergo a physical examination at a mobile examination center. The procedures followed to select the representative sample and conduct the interview and examinations are carefully outlined in the National Center for Health Statistics Analytic Guidelines (2006) and informed consent is obtained from all participants. All data, including that used in this study, are available online through the NHANES Web site.

NHANES participants 40 years and older were asked to participate in the ABI section of the lower extremity disease examination. Persons were excluded from the examination if they had a bilateral amputation or weighed more than 400 pounds (due to equipment limitations). Some participants who were eligible for the assessment might not have received the examination due to multiple reasons (eg, casts, ulcers, dressings, or other conditions that interfered with testing, equipment failure, participant refusal). The lower extremity disease examination was performed by trained health technicians in a specially equipped room in the mobile examination center and following a prescribed protocol.

The NHANES ABI is automatically calculated by their computer system and verified by the National Center for Health Statistics before data release. The right ABI was determined by dividing the mean systolic BP in the right ankle by the mean systolic BP in the brachial artery of the arm. The left ABI was computed in the same way using only measurements from the left extremities. The mean BP value for the arm and ankles are computed based on the first and second readings at each site. Since the second reading for all persons older than 60 were missing, the mean values are in fact the first recorded BP readings at a site. The presence of PAD was defined as an ankle‐brachial index <0.9.

MetS, as defined by the National Cholesterol Education Program (NECP) Third Report of the Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III), is present when any 3 of the following 5 traits exist in the same individual: abdominal obesity (waist circumference >102 cm [40 in] in men and >88 cm [35 in] in women); serum triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL; HDL cholesterol <40 mg/dL in men and <50 mg/dL in women; BP ≥130/85 mm Hg; and a fasting blood glucose ≥110 mg/dL.

Demographic variables including age and race/ethnicity were assessed in this study using data from the NHANES demographic questionnaire. Race/ethnicity was classified as non‐Hispanic white, non‐Hispanic black, and Hispanic. Individuals were classified as asymptomatic if they answered “no” to all of the following: Has a doctor told you that you have had a myocardial infarction? Has a doctor told you that you have had a stroke? Has a doctor told you that you have coronary heart disease? Has a doctor told you that you have had angina?

All estimates were weighted, with the sample weights accounting for the unequal selection probability of the complex NHANES sampling and the oversampling of selected population subgroups. Weights are created in NHANES to account for the complex survey design (including oversampling), survey nonresponse, and post‐stratification. When a sample is weighted in NHANES II it is representative of the US Census civilian noninstitutionalized population. A sample weight is assigned to each sample person. It is a measure of the number of people in the population represented by that sample person.

Results

MetS Prevalence in Persons With PAD

The prevalence of MetS in asymptomatic US adults 40 years and older during the 3 NHANES survey periods was 22.8%, while the prevalence of MetS in individuals with and without PAD was 38.4% and 22.2%, respectively (Table I).

Table I.

Prevalence of MetS in Asymptomatic US Adults 40 Years and Older With and Without PAD

| MetS(+) and PAD(−) (N=43,720,682) | MetS(+) and PAD(+) (N=3,287,736) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHANES | 1999–2000 | 2001–2002 | 2003–2004 | Total | 1999–2000 | 2001–2002 | 2003–2004 | Total |

| MetS, % | 22.9 | 20.8 | 23.3 | 22.2 | 38.3 | 36.5 | 41.4 | 38.4 |

Abbreviations: MetS, metabolic syndrome; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; PAD, peripheral arterial disease.

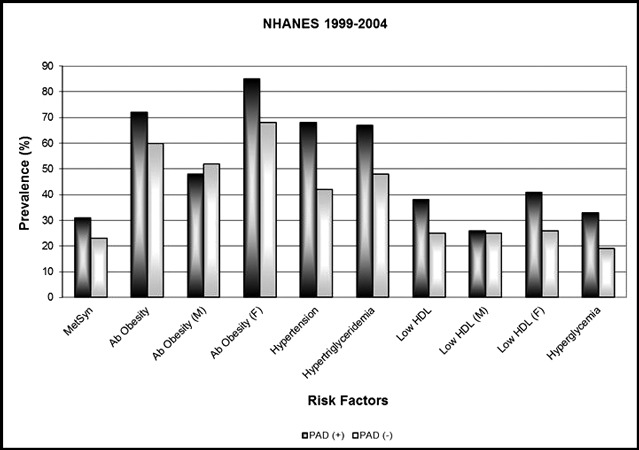

Women with PAD had a higher prevalence of MetS than do men. Non‐Hispanic black patients with PAD had a lower incidence of MetS than either non‐Hispanic white or Mexican American/other Hispanic individuals (Table II). Women with MetS also had a higher prevalence of abdominal obesity and had a generally higher prevalence of low HDL cholesterol in each of the 3 NHANES surveys (Figure).

Table II.

Prevalence of the MetS in Asymptomatic US Adults 40 Years and Older With a Prior Diagnosis of PAD: Sex, Race/Ethnicity, and MetS Components

| NHANES | MetS(+)/PAD(+) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999–2000, % | 2001–2002, % | 2003–2004, % | Total, % | |

| Women | 48.8 | 37.3 | 48.6 | 43.9 |

| Men | 24.0 | 35.0 | 24.3 | 28.6 |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 40.4 | 17.5 | 17.3 | 24.5 |

| Non‐Hispanic white | 37.2 | 39.0 | 50.0 | 41.5 |

| Mexican American/other Hispanic | 40.9 | 46.1 | 27.0 | 38.9 |

| aAbdominal obesity | 54.8 | 51.6 | 56.0 | 53.8 |

| Men | 41.9 | 58.2 | 40.7 | 50.2 |

| Women | 58.6 | 48.55 | 59.7 | 55.1 |

| Triglycerides >150 mg/dL | 87.8 | 74.2 | 76.5 | 78.8 |

| HDL cholesterol | 79.1 | 68.5 | 77.8 | 74.7 |

| <40 mg/dL (men) | 66.4 | 58.9 | 57.9 | 61.2 |

| <50 mg/dL (women) | 84.8 | 76.1 | 83.0 | 81.5 |

| bHypertension | 45.7 | 47.1 | 47.0 | 46.7 |

| cFasting glucose | 81.3 | 74.2 | 74.1 | 76.2 |

Abbreviations: HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; MetS, metabolic syndrome; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; PAD, peripheral arterial disease. aAbdominal obesity: waist circumference ≥102 cm (men) or ≥88 cm (women). bHypertension: blood pressure ≥130/85 mm Hg or treatment for hypertension. cFasting plasma glucose >110 mg/dL.

Figure FIGURE.

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) factors in individuals by peripheral arterial disease (PAD) diagnosis.

PAD Prevalence in Persons With MetS

The prevalence of PAD in asymptomatic US adults 40 years and older during the 3 NHANES survey periods was 4.2%. Overall, the prevalence of PAD in individuals with the MetS was 7.0% (Table III). In persons with MetS, women had a higher prevalence of PAD than men. Non‐Hispanic black individuals with MetS had a higher prevalence of PAD than did non‐Hispanic white or Mexican American/other Hispanics (Table IV).

Table III.

Prevalence of PAD in Asymptomatic US Adults 40 Years and Older With and Without MetS

| PAD(+) and MetS(−) (N=5,263,043) | PAD(+) and MetS(+) (N=3,287,7360) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHANES | 1999–2000 | 2001–2002 | 2003–2004 | Total | 1999–2000 | 2001–2002 | 2003–2004 | Total |

| PAD, % | 3.0 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 6.0 | 7.2 | 8.0 | 7.0 |

Abbreviations: MetS, metabolic syndrome; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; PAD, peripheral arterial disease.

Table IV.

Prevalence of PAD in Asymptomatic US Adults 40 Years and Older With a Prior Diagnosis of MetS: Sex, Race/Ethnicity, and MetS Components

| NHANES | PAD(+)/MetS(+) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999–2000, % | 2001–2002, % | 2003–2004, % | Total, % | |

| Women | 7.6 | 9.3 | 11.8 | 9.4 |

| Men | 3.8 | 5.0 | 3.1 | 4.1 |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 17.0 | 6.8 | 13.2 | 12.0 |

| Non‐Hispanic white | 5.6 | 7.8 | 8.0 | 7.2 |

| Mexican American/other Hispanic | 17.0 | 6.8 | 4.8 | 4.6 |

| aAbdominal obesity | 4.9 | 7.1 | 8.0 | 6.6 |

| Men | 2.2 | 5.6 | 2.7 | 3.7 |

| Women | 6.7 | 8.4 | 11.9 | 8.8 |

| Triglycerides >150 mg/dL | 6.4 | 6.0 | 8.1 | 6.7 |

| HDL cholesterol | 6.8 | 6.4 | 8.0 | 6.9 |

| <40 mg/dL (for men) | 4.4 | 5.2 | 3.0 | 4.4 |

| <50 mg/dL (for women) | 8.5 | 7.4 | 11.5 | 8.9 |

| bHypertension | 5.8 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 7.6 |

| cFasting glucose | 8.0 | 7.3 | 7.6 | 7.6 |

Abbreviations: HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; MetS, metabolic syndrome; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; PAD, peripheral arterial disease. aAbdominal obesity: waist circumference ≥102 cm (men) or ≥88 cm (women). bHypertension: blood pressure ≥130/85 mm Hg or treatment for hypertension. cFasting plasma glucose >110 mg/dL.

Prevalence of MetS Clinical Factors

Individuals with PAD had a significantly higher prevalence of MetS and its associated clinical factors (Figure). In the total population studied, all MetS clinical factors were more prevalent in persons with PAD compared with persons without PAD. When stratifying the prevalence of MetS clinical factors by sex, the prevalence of abdominal obesity and low HDL was higher in women with PAD than those without, but was similar in men with and without PAD.

Discussion

In this observational study of asymptomatic US adults 40 years and older, we found that (1) individuals with PAD had a significantly higher prevalence of MetS than did those without PAD and (2) individuals with MetS have a higher prevalence of PAD.

In the literature, estimates of the prevalence of MetS have differed depending on the definition (NCEP/ATP III, World Health Organization, International Diabetes Federation, European Group for the Study of Insulin Resistance) used to categorize individuals, study population, and measurement methods. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 Prevalence estimates have increased over time across 2 NHANES cohorts from approximately 24.1% (1988–1994 cohort) to 27% (1999–2000 cohort). The cause of this increase is thought to be due to differences in the compositions of the cohorts. 15 Our estimate of MetS prevalence is nearly identical to that from NHANES III, which reported an age‐adjusted MetS prevalence of 24% among US adults. 16

In the present study, we found that MetS was present in a higher number of individuals with PAD as compared with those without PAD. These results are consistent with the findings of Gorter and colleagues 17 who found that in PAD, MetS is highly prevalent. Other cross‐sectional studies have reported an even higher prevalence of MetS in patients with PAD (57%–60%). 18 , 19 The highest prevalence of 97% was reported by Qadan and associates, 20 but their investigation included patients with clinically advanced PAD. These different estimates of PAD prevalence are likely due to differences in study size and population.

It is interesting to note that the Edinburgh Artery Study did not find a significant association between MetS and incident PAD (hazard ratio, 0.89; 95% confidence interval, 0.57–1.38). 21 This lack of association between MetS and PAD may be due to differences in the study population. The Edinburgh cohort was older (mean age, 65 years), had a high prevalence of baseline smoking status (25.3%), and represented a cohort of patients with symptomatic PAD. Moreover, components of MetS were measured differently relative to our study. The Edinburg Artery Study did not use waist circumference measurement for evaluating body mass index. Instead, it used a proxy measure of body mass index. 21

In the current study, we also found that the prevalence of MetS in a person with PAD varied between women and men, with a higher prevalence of MetS in women with PAD than in men. Other researchers have reported similar findings, observing a higher prevalence of MetS in women with PAD than men. 17 , 22 We also found that women with MetS have a higher prevalence of asymptomatic PAD than do men. This finding adds to the existing data of Conen and colleagues 23 who found that MetS was associated with a higher risk of developing future symptomatic PAD in women. The researchers in that study suggested that the risk appears to be largely mediated by the effect of inflammation and endothelial activation especially since women with MetS in that study had a higher level of C‐reactive protein than did those without MetS. Other researchers have described an association between inflammation and PAD. 22 , 23 Our data put into context the public health significance of this association within a representative sample of the total US population.

Abdominal obesity was the most prevalent component of the MetS in our PAD population. When stratified by sex, the prevalence of abdominal obesity was higher in women with PAD, but was similar in men with and without PAD. Hypertension was the second most prevalent MetS component in our study. In the Secondary Manifestation of ARTerial disease (SMART) study and the work of Brevetti and colleagues, 17 , 22 hypertension was the MetS component observed most commonly in patients with PAD. This difference in MetS component prevalence is likely due to the fact that those were smaller studies (1117 patients and 154 patients, respectively) and represented an older cohort. This difference in prevalence of risk factors for MetS may be important because abdominal obesity plays an important role in insulin resistance, which is regarded as the primary etiologic process of MetS. 24 Epidemiologic and pathophysiologic data indicate that visceral obesity is a main factor in the occurrence of the MetS. 25 , 26 We also found that all of the MetS clinical components were more prevalent in the PAD population compared with the population without PAD.

In terms of race and ethnicity, we found that non‐Hispanic black individuals with MetS had a higher prevalence of PAD than did non‐Hispanic whites or Mexican Americans/other Hispanics. We also found that non‐Hispanic whites with PAD have a higher incidence of MetS than either non‐Hispanic blacks or Mexican Americans/other Hispanic individuals. Our data represent the first assessment of race and ethnicity as a stratifying factor for examining the relationship between PAD and MetS prevalence.

Limitations

The present study should be interpreted in the context of several potential limitations. First, our study did not include data on markers of subclinical inflammation such as high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein or markers of endothelial injury or activation. Second, data regarding cigarette smoking were not collected. Third, our study assessed the prevalence of MetS in a population of patients with PAD and vice versa, but did not evaluate a causal relationship between the presence of MetS and PAD. Fourth, our data do not evaluate the effect of MetS and PAD on clinical outcomes.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate a high prevalence of PAD in asymptomatic US adults 40 years and older with MetS and also a high prevalence of MetS in the population of asymptomatic persons with PAD. These findings support screening patients with PAD for MetS, and vice versa, so as to identify a group of patients at potentially high cardiovascular risk.

Disclosures: None of the manuscript authors have any commercial associations that might create a conflict of interest associated with this submission.

References

- 1. Wild SH, Byrne CD, Smith FB, et al. Low ankle‐brachial pressure index predicts increased risk of cardiovascular disease independent of the metabolic syndrome and conventional cardiovascular risk factors in the Edinburgh Artery Study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:637–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Feringa HH, Karagiannis SE, Schouten O, et al. Prognostic significance of declining ankle‐brachial index values in patients with suspected or known peripheral arterial disease. Eur J Vas Endovasc Surg. 2007;34:206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sutton‐Tyrrell K, Venkitachalam L, Kanaya AM, et al. The Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. Stroke. 2008;39:863–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Leng GC, Fowkes FGR, Lee AJ, et al. Use of ankle brachial pressure index to predict cardiovascular events and death: a cohort study. BMJ. 1996;313:1440–1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Makowsky MJ, McAlister FA, Galbraith PD, et al. Lower extremity peripheral arterial disease in individuals with coronary artery disease: prognostic importance care gaps, and impact of therapy. Am Heart J. 2008;155:348–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Diehm C, Allenberg JR, Pittrow D, et al. Mortality and vascular morbidity in older adults with asymptomatic versus symptomatic peripheral artery disease. Circulation. 2009;21:2053–2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Isomaa B, Almgren P, Tuomi T, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:683–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lakka HM, Laaksonen DE, Lakka TA, et al. The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle‐aged men. JAMA. 2002;288:2709–2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Isomaa B, Henricsson M, Almgren P, et al. The metabolic syndrome influences the risk of chronic complications in patients with type II diabetes. Diabetologia. 2001;44:1148–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alexander CM, Landsman PB, Teutsch SM, Haffner SM. NCEP defined metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and prevalence of coronary heart disease among NHANES III participants age 50 years and older. Diabetes. 2003;52:1210–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Conen D, Rexrode KM, Creager MA, et al. Metabolic syndrome, inflammation, and risk of symptomatic peripheral artery disease in women: a prospective study. Circulation. 2009;120(12):1041–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schmidt MI, Watson RL, Duncan BB, et al. Clustering of dyslipidemia, hyperuricemia, diabetes, and hypertension and its association with fasting insulin and central and overall obesity in a general population. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study Investigators. Metabolism. 1996;45(6):699–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Després JP. Is visceral obesity the cause of the metabolic syndrome? Ann Med. 2006;38(1):52–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shuldiner AR, Yang R, Gong DW. Resistin, obesity and insulin resistance. The emerging role of the adipocyte as an endocrine organ. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1345–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) . Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15:539–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. Metabolic syndrome – a new world‐wide definition. A Consensus Statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet Med. 2006;23:469–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 2002;287:356–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Qadan LR, Ahmed AA, Safar HA, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with clinically advanced peripheral vascular disease. Angiology. 2008;59:198–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gorter PM, Olijhoek JK, van der Graaf Y, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral arterial disease or abdominal aortic aneurysm. Atherosclerosis. 2004;173:363–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brevetti G, Schiano V, Sirico G, et al. Metabolic syndrome in peripheral arterial disease: relationship with severity of peripheral circulatory insufficiency, inflammatory status, and cardiovascular morbidity. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:101–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maksimovic M, Vlajinac H, Radak D, et al. Relationship between peripheral arterial disease and metabolic syndrome. Angiology. 2009;60(5):546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Olijhoek JK, van der Graaf Y, Banga JD, et al. The metabolic syndrome is associated with advanced vascular damage in patients with coronary heart disease, stroke, peripheral arterial disease or abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:342–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wild SH, Byrne CD, Tzoulaki I, et al. Metabolic syndrome, haemostatic and inflammatory markers, cerebrovascular and peripheral arterial disease: The Edinburgh Artery Study. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203(2):604–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Balkau B, Charles MA. Comment on the provisional report from the WHO consultation. European Group for the Study of Insulin Resistance (EGIR). Diabet Med. 1999;16:442–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cornier MA, Dabelea D, Hernandez TL, et al. The metabolic syndrome. Endocr Rev. 2008;29(7):777–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]