Abstract

Hypertension is a major cardiovascular (CV) risk factor, but several other common conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), osteoporosis, and peripheral arterial disease (PAD), have been shown to independently increase the risk of CV events and death. The physiological basis for an increased CV risk in those conditions probably lies in the augmentations of oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, systemic inflammation, and arterial stiffness, which all are also hallmarks of hypertension. β‐Blockers have been used for the treatment of hypertension for more than 40 years, but a number of meta‐analyses have demonstrated that treatment with these agents may be associated with an increased risk of CV events and mortality. However, the majority of primary prevention β‐blocker trials employed atenolol, an earlier‐generation β1‐selective blocker whose mechanism of action is based on a reduction of cardiac output. Available evidence suggests that vasodilatory β‐blockers may be free of the deleterious effects of atenolol. The purpose of this review is to summarize pathophysiologic mechanisms thought to be responsible for the increased CV risk associated with COPD, osteoporosis, and PAD, and examine the possible benefits of vasodilatory β‐blockade in those conditions. Our examination focused on nebivolol, a β1‐selective agent with vasodilatory effects most likely mediated via β3 activation.

For many years, diabetes was considered to be an endocrine disease; however, recognition of diabetes as a vascular disease improved understanding and therapeutic intervention, resulting in significant decreases in morbidity and mortality. 1 , 2 Recently, a number of other common conditions have been shown to be associated with significant increases in cardiovascular (CV) risk. These include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), 3 osteoporosis, 4 peripheral arterial disease (PAD), 5 and rheumatoid arthritis. 6

β‐Blockers have been used for more than 40 years for the treatment of hypertension and, more recently, heart failure (HF), 7 for which they are still recommended as first‐line therapy. 8 Available meta‐analyses, however, involving patients with essential hypertension—with one recent exception 9 —have suggested that β‐blockers may not be associated with long‐term benefits, compared with placebo, 10 , 11 or that they even may be associated with an increased risk of CV events and all‐cause mortality in individuals without a history of myocardial infarction and HF. 12 However, the majority of the trials included in those analyses employed atenolol, an earlier‐generation β‐blocker whose mechanism of action is based on a reduction of cardiac output. 7 , 10 Vasodilatory β‐blockers may be free of the potentially deleterious effects of atenolol. 13 Two of three vasodilatory β‐blockers in clinical use, carvedilol and labetalol, are thought to exert their relaxation effects via α1‐adrenergic blockade; 13 the third agent, nebivolol, is a β1‐selective (ie, cardioselective) adrenergic receptor antagonist (at doses up to 10 mg/d), with vasodilatory effects mediated by nitric oxide (NO) release, 14 a mechanism possibly triggered by activation of β3‐receptors. 15

The purpose of this review is to summarize pathophysiologic mechanisms thought to be responsible for the increased CV risk associated with COPD, osteoporosis, and PAD, and examine the possible benefits of vasodilatory β‐blockade in these conditions. Our examination focused on nebivolol, due to its purported β‐receptor–mediated mechanism of vasodilation. 15

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

COPD is a heterogeneous chronic condition characterized by a progressive airflow limitation that is not fully reversible by current therapies. 16 The worldwide prevalence of COPD has been estimated at 7.6% to 26.1%, with age and smoking history being the most significant risk factors. 17 , 18 It also has been estimated that COPD will be the third leading cause of death worldwide by 2020. 19 COPD is associated with a number of comorbidities, which include hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, HF, and CV disease (CVD) in general. 20

Since cigarette smoking is the major risk factor for the development of COPD and a major risk factor for the development of CVD, 20 it is tempting to attribute the entire augmentation of CV risk in patients with COPD to smoking; however, a 2005 review article by Sin and Man 3 summarized the growing body of epidemiologic evidence (4 studies with a total of 26,265 participants 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ) that suggested a strong, smoking‐independent association between compromised lung function and increased CVD risk. 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 The Sin and Man review 3 also covered the studies that examined the association of CV risk and the rate of decline in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), including a report based on the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (N=883), which demonstrated a 5‐ to 10‐fold increase in CV mortality in lifetime nonsmokers who experienced a rapid decline in FEV1. 25 Finally, results of a large 2009 US cohort study that included 18,342 participants (40 years and older) of the 2002 National Health Interview Survey suggest a strong positive correlation between COPD and CV risk, even after simultaneous adjustment for comorbidities, sociodemographic factors, and lifestyle parameters, including smoking. A case‐control analysis within that same study also found a smoking‐independent effect of COPD on CVD morbidity. 26 The underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms that are responsible for the increased CV risk in COPD remain unclear, but may include arterial stiffness, 27 inflammation, 28 and endothelial dysfunction. 29

COPD and Arterial Stiffness

In recent years, a number of population‐based studies have identified increased arterial stiffness as a major independent risk factor for CVD, 30 a finding that has also been confirmed in a recent meta‐analysis. 31 For example, a study conducted by Sabit and colleagues 27 demonstrated that the aortic pulse wave velocity (aPWV) and the augmentation index (AIx) (both measures of arterial stiffness) were significantly greater in patients with COPD (n=75) than in age‐matched controls (n=42). In addition, patients with COPD and osteoporosis had a significantly higher aPWV than those without osteoporosis. aPWV was also significantly associated with age, interleukin (IL) 6 levels, and the inverse value of the FEV1. 27 These findings are consistent with the results of the Caerphilly Prospective Study, which recruited a cohort of men only (N=827) and demonstrated a significant correlation between mid‐life levels of lung function (FEV1, forced vital capacity [FVC]) with later‐in‐life levels of arterial stiffness (as measured using aPWV). 32 Further support for an association between arterial stiffness and lung function came from an analysis of data accumulated within the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III, 1988–1994; N=13,090), which revealed a significant correlation between decreased lung function (assessed by means of FEV1) and increased pulse pressure, 33 a surrogate measure of arterial stiffness, in individuals older than 40 years. Prospective longitudinal studies will be required to assess the predictive value of aPWV for CV events in patients with COPD. 34

A further link between COPD and adverse CV outcomes may be diastolic HF, which is a common finding in patients with COPD. 35 Indeed, increased arterial stiffness is associated with diastolic HF, 36 and a recent study has shown that increased aPWV is strongly associated with left ventricular function in patients with COPD. 37 In addition to diastolic HF, COPD has been shown to coexist with systolic HF, at least in the elderly. 38

COPD and Inflammation

It has been suggested that chronic extrapulmonary systemic inflammation may mediate the link between COPD, arterial stiffness, and increased CV risk. 39 Plasma levels of C‐reactive protein (CRP), a marker of systemic inflammation, have been demonstrated to increase the risk of developing hypertension, 40 with CRP concentration being related to 24‐hour levels of systolic and pulse pressure, but not diastolic pressure. 41 In addition, blood pressure (BP) and CRP levels have been shown to be independent determinants of CV risk, with an additive predictive value. 42

The abovementioned study by Sabit and associates demonstrated increased levels of inflammatory markers, such as IL‐6 and the soluble receptors for the tumor necrosis factor α (TNF‐α), in patients with COPD, which correlated with lung function and arterial stiffness. 27 Other studies have also demonstrated correlations between the severity of airflow obstruction and markers of systemic inflammation, both molecular (fibrinogen and CRP) 39 , 43 and cellular (leukocytes and platelets). 39 Finally, the association between COPD and systemic inflammation is supported by a systemic review and meta‐analysis of 14 studies, which demonstrated reduced lung function to be significantly associated with increased levels of CRP, TNF‐α, and fibrinogen, and with an increased number of circulating leukocytes. 28

In patients with COPD, increased inflammatory markers have also been associated with increased pulmonary artery pressure, 44 CV risk, 39 and all‐cause, CV, and cancer‐specific mortality. 45 In an epidemiologic study that did not restrict its participants to those with COPD (Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease [BOLD] study), hypertension, body mass index (BMI), and systemic inflammation were found to affect lung function independently of each other. In addition, significant correlations between hypertension and lower‐than‐predicted values of FEV1 and FVC were maintained even after adjusting for age, BMI, CRP levels, and smoking status. 46 The accumulating evidence linking COPD with hypertension and other chronic conditions (eg, diabetes, metabolic syndrome) prompted Fabbri and Rabe 47 to propose the addition of the term “chronic systemic inflammation syndrome” to the diagnosis of COPD, and to single out CRP as a possible “sentinel biomarker for all chronic diseases.” Consistent with these observations, a recent trial that employed positron emission tomography (PET) demonstrated excessive inflammation of the aorta in patients with COPD, 48 which, may, in part, explain the increased aPWV demonstrated in patients with COPD. 49

Based on the observations that hypertension is common in patients with COPD, 50 that both conditions have been associated with arterial stiffness, 27 and that COPD, hypertension, and arterial stiffness have all been associated with increased levels of inflammation markers, 28 , 40 it has been suggested that low‐grade systemic inflammation in patients with COPD may lead to increases in arterial stiffness, which may increase CV risk directly via adverse hemodynamic effects or indirectly via promoting isolated systolic hypertension. 51

COPD and Endothelial Dysfunction

Since arterial stiffness is regulated in part by endothelium‐derived NO, 52 impaired endothelial function may be a potential mechanism mediating increased arterial stiffness and CV risk in patients with COPD. Studies involving individuals with and without CV comorbidities demonstrated that both endothelium‐dependent and endothelium‐independent vasodilation were significantly impaired in COPD, with the degree of impairment being proportional to the severity of airflow obstruction. 29 , 53 , 54

β‐Blockers in Patients With Hypertension and COPD

Initially, β‐blockers were considered contraindicated in patients with COPD, since β2‐antagonism would be expected to increase bronchoconstriction and thus exacerbate COPD symptoms. 55 However, a 2005 Cochrane Collaboration meta‐analysis summarized the results of 20 randomized trials of β1‐selective (ie, cardioselective) blockers (acetobutolol, atenolol, bisoprolol, celiprolol, metoprolol, and practolol; N=680), and concluded that those agents—regardless if used once, or repeatedly, over the period of 2–84 days—did not induce changes in FEV1 or respiratory symptoms, compared with placebo, nor did they affect FEV1 response to β2‐agonists. 56

Based on the evidence that the increased CV risk associated with COPD may be mediated by increased arterial stiffness, inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and the probable interrelationship between these parameters, it has been suggested that a β‐blocker with anti‐inflammatory effects that also increases NO production could decrease arterial stiffness in COPD and hence improve CV outcomes. 57 Indeed, there is already indirect evidence that anti‐inflammatory agents such as steroids may decrease the likelihood of CV events in patients with COPD. 58 Furthermore, results of a case‐control retrospective study suggest that therapeutic interventions that may decrease arterial stiffness and improve endothelial function, such as statins, 59 angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, 60 and angiotensin II receptor blockers, 60 are also associated with fewer CV events in individuals with COPD, even when those receiving steroid therapy are included. 61

In addition to its cardioselectivity and NO‐mediated vasodilatory effects, 62 nebivolol has been demonstrated to have anti‐inflammatory effects, 63 to improve endothelial function, 64 , 65 and to decrease arterial stiffness, 66 suggesting that nebivolol therapy in COPD may be associated with clinical benefits beyond BP reduction (Table). 67

Table TABLE.

Effects of Some Hypertension‐Associated Diseases and the Related Effects of Nebivolol

| Effect | Hypertension‐Associated Diseases | Antihypertensive Treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COPD | Osteoporosis | PAD | Nebivolol | |

| Clinical | ||||

| CV risk | ↑ 20 | ↑ 81 | ↑ 5 | ↓a |

| Arterial stiffness | ↑ 27 | ↑ 83 | ↑ 118 | ↓ 14 , 66 |

| Blood pressure | ↑ 20 | ↑ 80 | ↑ 5 | ↓ 62 |

| Heart failure | ↑ 130 | ↑ 132 | ↑ 133 | Benefits in seniors 134 |

| Bone fractures | ↑ 97 | ↑ 78 | ↑ 127 | Benefits plausible 108 , 109 , 110 |

| Biological | ||||

| SNS activity | ↑ 135 | ↑ 102 , 103 | N/A | ↓ 62 |

| Systemic inflammation | ↑ 28 | ↑ 87 | ↑ 121 | ↓ 63 |

| Endothelial dysfunction | ↑ 54 | ↑ 98 | ↑ 120 | Improvements observed in vitro 104 and in vivo 65 |

| Oxidative stress | ↑ 136 | ↑ 137 | ↑ 122 | ↓ 64 |

aData available for elderly patients with heart failure only (SENIORS trial). 134 The symbol “↑” indicates positive correlation, greater risk, or increase; “↓” indicates negative correlation, lower risk, or reduction. Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CV, cardiovascular; N/A, evidence is limited or not available; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; SNS, sympathetic nervous system.

So far, only short‐term, smaller studies of nebivolol in patients with respiratory problems have been conducted. 68 , 69 , 70 Thus, in a single‐blind, crossover, 2‐week trial involving individuals with COPD (N=20), nebivolol treatment was associated with a statistically significant, but perhaps not clinically relevant, mean reduction of 9.4% in FEV1 (or −0.109 L, with 95% confidence interval ranging from −0.043 L to −0.175 L). 68 In addition, a 1‐month open‐label trial of 30 patients with stage 1 chronic obstructive bronchitis showed that nebivolol did not cause worsening of spirometric parameters, 68 and in a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, crossover study of patients with bronchial hyper‐reactivity due to COPD, asthma, or an unknown cause (N=24), nebivolol did not have significant effects on airflow obstruction. 70

It is worth noting that carvedilol, a nonselective β‐blocker with vasodilatory activity mediated via α1‐adrenergic blockade, 13 has been studied in patients with coexisting chronic HF (CHF) and COPD, and the effects on lung function remain inconclusive. One study found that the addition of carvedilol to the treatment regimen of patients with CHF and COPD did not result in significant airflow limitation, 71 whereas another study showed that switching from a β1‐selective blocker (metoprolol) to carvedilol resulted in a demonstrable reduction in lung function. 72

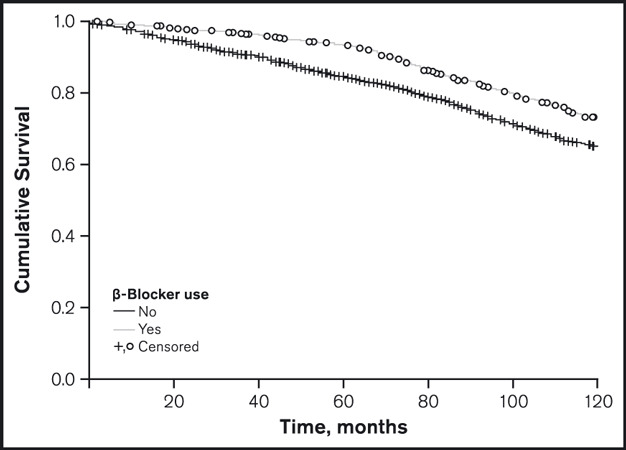

Interestingly, one cohort study published in 2004 (N=1966) demonstrated a nonsignificant reduction in all‐cause mortality among patients with COPD and hypertension treated with β‐blockers, 73 and a recent observational cohort study of patients with COPD (N=2230) demonstrated that users of β‐blockers (cardioselective or nonselective) had a significantly higher survival rate than nonusers (Figure 1). 74 In addition, that study showed that the use of cardioselective β‐blockers in patients both with and without overt CV comorbidities was associated with significantly lower odds of all‐cause mortality and COPD exacerbations, even after adjustment for presence of CVDs and hypertension, and that the effect on COPD exacerbations remained significant even in users of nonselective β‐blockers. 74 In addition, a recent cohort study based on Scottish morbidity records (N=5977) suggests that β‐blocker use in patients with COPD, when added to established inhaled therapy (including long‐lasting β‐agonists), results in a significant reduction in all‐cause, cardiac, and respiratory mortality; emergency oral steroid prescriptions; and hospital admissions due to COPD. 75 The benefits appeared independent of overt CVD and use of other CV drugs and were not associated with adverse effects on pulmonary function. 75 The fact that a similar risk reduction was observed for both cardiac and respiratory outcomes suggests that β‐blocker benefits in COPD may indeed occur beyond their effects on BP. 75

Figure 1.

The use of β‐blockers in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is associated with a higher survival rate than non‐use. The symbols “+” and “o” denote time points at which individuals who were (“o”) and were not (“+”) taking β‐blockers either died or dropped out of the study (ie, were “censored”). Adapted with permission from Rutten and colleagues. 74

Although the hypothesis that nebivolol use in patients with COPD would be safe and possibly even associated with benefits on “hard” outcomes (eg, survival rate) is supported by the outcomes of 3 small randomized trials, 68 , 69 , 70 a meta‐analysis of trials involving other cardioselective β‐blockers, 56 and 3 large cohort studies of β‐blocker use in COPD, 73 , 74 , 75 it is important to stress that at this point such a notion is just conjecture, based on indirect evidence. For example, therapies targeted for COPD due to their anti‐inflammatory potential have been shown both to succeed 76 and fail 77 in clinical studies. Prospective randomized trials would be required to provide a satisfactory answer to the question of risks and benefits associated with nebivolol use in patients with this disease.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is characterized by decreased bone mineral density (BMD), which results in increased bone fragility and fracture risk. 78 It is estimated that approximately 50% of women and 25% of men aged 50 or older will experience an osteoporosis‐related fracture in their lifetime. 78 Due to an aging population (both in developed and developing countries), it is possible that the number of osteoporosis‐related fractures may double over the next few decades. 78 Since the prevalence rates of osteoporosis, hypertension, CVD, and COPD all increase with age, it is likely that these conditions will coexist more frequently in modern aging societies. However, epidemiologic evidence suggests that osteoporosis and hypertension 80 and osteoporosis and CVD 81 also co‐occur independently of age or estrogen levels. In addition, significant correlations have been found between osteoporosis and CV mortality, independent of common CV risk factors, 4 and studies involving patients with osteoporosis have demonstrated inverse relationships between BMD and atherosclerosis, 82 arterial calcification, 83 and arterial stiffness. 84 Furthermore, aortic calcification has been associated with carotid 85 and aortic stiffness (together with isolated systolic hypertension). 86 A recent study involving apolipoprotein E–deficient (ApoE−/−) mice demonstrated that the calcification of arteries and the aortic valve correlated with a loss in BMD, and that calcification and osteoporosis both correlated with an increase in inflammatory markers. 87

It should be pointed out that the correlations between a decrease in BMD and changes in vasculature do not necessarily occur between sites that are in immediate proximity of each other. For example, calcification of the aorta has been found to independently contribute to the osteoporosis in the proximal femur, 88 and osteoporotic vertebral fractures were associated with an increased risk of atherosclerotic carotid plaques. 89 This relationship of distal phenomena points to a simultaneous response to blood‐borne factors at the two sites, or even to a cross‐talk between them.

Indeed, cells that show calcifying potential have been isolated from bovine aortic media, 90 the expression of bone morhpogenic protein (BMP) has been demonstrated in calcified human atherosclerotic lesions, 91 and different sets of constitutive and regulatory proteins of the bone (matrix Gla protein, osteocalcin, bone sialoprotein, BMP‐2, BMP‐4, osteopontin, osteonectin, osteoprotegerin, and osteoprotegerin ligand) have been found in atherosclerotic lesions and undiseased human aortas, with the expression profile consistent with the degree of calcification. 92 Furthermore, molecular mediators of inflammation associated with atherosclerosis, which also play a role in vascular calcification (eg, CRP, IL‐6, and TNF‐ α), 93 , 94 have also been shown to predict changes in BMD. 95 In addition to providing a functional link between osteoporosis and atherosclerosis (and thereby, between osteoporosis and arterial stiffness, hypertension, and CVD), low‐grade systemic inflammation 96 may explain the high prevalence of osteoporosis in patients with COPD. 97

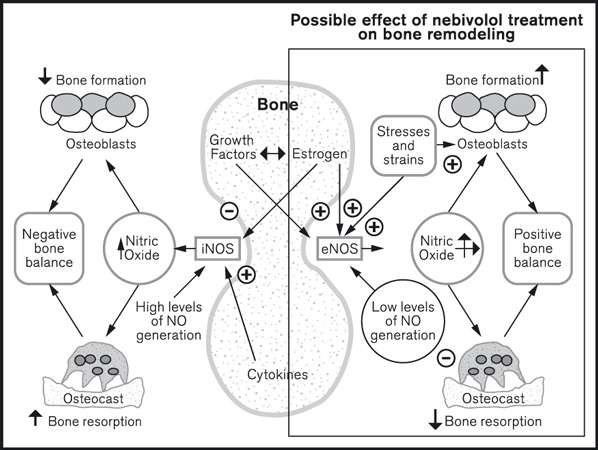

In addition to inflammatory cytokines, preclinical data indicate that NO also plays an essential role in bone remodeling, and most likely in a concentration‐dependent manner. A constant production of NO in small quantities has been associated with bone formation, whereas high or frequent spikes in NO levels have been shown to induce bone resorption. 98 , 99 Data obtained from clinical trials and epidemiologic studies provide some support for the view that treatment with NO donors (eg, nitroglycerine) may be effective for prevention of bone loss, but conclusive evidence is still lacking. 100

In addition, data obtained within the last decade provided evidence that bone remodeling is, in part, regulated by the sympathetic nervous system. For example, intracerebroventricular infusion of the appetite‐regulating peptide leptin in both leptin‐deficient and wild‐type mice has been shown to decrease bone mass, 101 an effect that was mediated by β2‐adrenergic receptors on the osteoblasts: stimulation and blockade of β2‐adrenergic receptors resulted in bone resorption and formation, respectively. 102 , 103

Observations that bone formation is stimulated by a steady increase in NO levels and the blockade of β2‐receptors support a possibility that nebivolol, a β‐blocker that induces NO release and loses its β1‐receptor selectivity for doses >10 mg/d, 62 could provide benefits for patients with osteoporosis (Figure 2). A study performed using human umbilical vein cells suggested that nebivolol‐induced activation of endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) occurs via activation of β3‐adrenergic receptors and estrogen receptors, 104 and eNOS has been suggested to play a role in estrogen‐ and NO‐mediated bone formation. 100 , 105 On the other hand, available evidence suggests that carvedilol, contrary to nebivolol, was not shown to increase eNOS immunoreactivity in the rat corpus cavernosum, 106 although a positive effect on eNOS expression and NO levels was observed in aortic tissue of diabetic rats. 107

Figure 2.

Steady low‐level rise in nitric oxide (NO) concentration induced by nebivolol treatment may facilitate bone formation. The symbols (+) and (−) denote positive and negative modulation, respectively: “↑” and “↓” indicate increase and decrease, respectively; eNOS, endothelial NO synthase; iNOS, inducible NO synthase. Adapted with permission from Wimalawansa. 100

Results of prospective randomized trials that evaluated the effects of β‐blocker treatment on BMD or fracture risk are not available, but a large case‐control analysis (N=30,601) found that β‐blocker use is associated with a significantly lower risk of fractures, even after adjustment for BMI, smoking status, and the use of other classes of antihypertensives. 108 Results of a meta‐analysis of such observational studies, comprising 7 studies of β‐blockers, were consistent with those findings. 109 The most recent published data, obtained within the Australian Dubbo Osteoporosis Epidemiology Study (DOES; N=3488), also demonstrated a significantly lower risk of fractures associated with β‐blocker use (and not with other classes of antihypertensives), in a manner independent of BMI, BMD, age, and other covariates. 110 Interestingly, the β‐blocker “effect” seems to be driven by cardioselective (ie, β1‐selective) agents, 110 which does not support the putative role of β2‐receptor blockade in bone formation, postulated above. 102 , 103 It is worth noting that the authors of the DOES analysis employed a propensity score approach, a relatively new statistical tool designed to create treatment and control groups with similar characteristics, in an attempt to emulate the baseline conditions of a randomized clinical trial. 111 , 112

In summary, osteoporosis is associated with systolic hypertension 80 and increased CV risk, 81 a phenomenon that may be driven by inflammation, 87 vascular calcification, 83 and the resulting increase in arterial stiffness. 84 Since sympathetic activation may cause a decrease in BMD, 102 , 103 a β‐blocker that could decrease inflammation and induce NO release may have benefits beyond BP reduction in hypertensive individuals with osteoporosis (Table). However, it also needs to be pointed out that all the evidence in support of nebivolol benefits for patients with osteoporosis is indirect, and that randomized prospective studies are needed to provide a definitive answer.

Peripheral Arterial Disease

PAD occurs when blood flow to the extremities is reduced, often by narrowed or blocked arteries; it has been estimated to affect 8 million people in the United States alone. 5 The prevalence of PAD increases with age, and diabetes and smoking status are prominent risk factors. 5 The classic symptom of PAD is intermittent claudication (exertional leg pain relieved by rest), although approximately 40% of patients affected do not complain of leg pain, and 50% have leg symptoms that are different from classic claudication. 5 PAD is indicative of widespread atherosclerosis; increases the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and death; and often reduces functional capacity required for normal activities of daily living. 5 , 113 Nevertheless, it remains underdiagnosed and undertreated, with only about 20% to 30% of patients receiving recommended therapy of antiplatelet and/or lipid‐lowering agents. 5 , 114

PAD has been associated with elevated arterial stiffness, 115 , 116 a phenomenon that may be partly caused by stiffening of the large central arteries (aortic, carotid), both via hemodynamic and structural mechanisms. 117 , 118 At the molecular and cellular level, markers that have been associated with PAD including those of vascular inflammation (CRP, IL‐6), thrombosis (fibrinogen), endothelial dysfunction (FMAD reduction), oxidative stress, metabolism (glucose), and angiogenesis. 119 , 120 , 121 , 122 Changes in these parameters have also been associated with other CVD, and may be common features that unite CV disorders along a continuum. 2

In addition, available literature suggests that PAD may coexist with COPD and osteoporosis. In a French cohort of patients hospitalized with PAD in lower extremities (N=940), approximately 27% experienced intermittent claudication and 17% of those had COPD, 123 and a small Polish study of patients with severe PAD (N=64) identified 25 individuals (39%) who also had COPD. 124 In a Spanish cohort of patients with COPD (N=572), PAD was detected in 17% of all individuals, 125 and in a French study involving 151 patients with COPD, 81% were also diagnosed with PAD. 126 In addition, a study involving 345 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis and 360 age‐matched controls with normal BMD, PAD was detected in 18.2% and 3.8% of individuals, respectively (P<.001). 127

In spite of PAD being a risk factor for hypertension 128 and vice versa, 129 trials that examined the effects of β‐blockers on symptoms of PAD were scarce: a 2009 Cochrane Collaboration meta‐analysis identified 6 randomized controlled trials of atenolol, pindolol, propranolol, and metoprolol, with a total of 119 patients, and found no evidence that β‐blockers adversely affected walking distance in patients with intermittent claudication. 132 Similar to COPD and osteoporosis, it is reasonable to speculate that vasodilatory effects of β‐blockers such as nebivolol and carvedilol 13 would provide clinical benefits beyond BP reduction in patients with PAD (Table), but that hypothesis still needs to be verified in prospective randomized trials.

Conclusions

A majority of available meta‐analyses, mostly based on atenolol trials, have suggested that β‐blockers, unlike other antihypertensive agents, either do not influence or may even augment the risk of CV events. However, available data indicate that vasodilatory β‐blockers such as nebivolol may be devoid of some of the deleterious effects of atenolol. Until recently, β‐adrenergic blockade has been contraindicated for hypertensive patients with impaired lung function and COPD, but a large body of evidence now suggests that the use of β‐blockers—and cardioselective β‐blockers in particular—would be safe in individuals with COPD, and that it actually may decrease the risk of all‐cause and CV mortality. Although β‐adrenergic blockade has not been contraindicated in hypertensive patients with osteoporosis, the accumulating evidence suggests that β‐blockers may reduce the risk of fractures in such patients, ie, provide benefits beyond BP lowering. In terms of receptor affinity, individuals with COPD and osteoporosis may benefit from different types of β‐blockade (β1‐selective and ‐nonselective, respectively), and they all would likely benefit from an agent with anti‐inflammatory activity that also enhances NO production and endothelial function. Such agents may also be beneficial for other conditions associated with hypertension, such as peripheral arterial disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Although atenolol probably no longer should be used to treat hypertension, nebivolol may not be associated with the same risks: its cardioselective, vasodilatory, anti‐inflammatory, and endothelium‐sparing effects should not only make it a suitable alternative for the treatment of hypertension, but may also provide additional benefits in patients with associated conditions, such as COPD and osteoporosis. A definitive answer to the existence of those benefits would have to come from prospective randomized controlled trials.

Acknowledgements and disclosures: The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of Liz Artwick, Morgan Hill, PhD, Merrilee Johnstone, PhD, Autumn Kelly, MA, Vojislav Pejović, PhD, and Regina Switzer, PhD, employees of the Prescott Group, who assisted with research and formatting, provided editorial assistance, and formatted the manuscript for submission. John Cockcroft has received honoraria for advisory board meetings and research funding from Forest Pharmaceuticals. Michala E. Pedersen has no conflict of interest to declare. This work was sponsored by Forest Laboratories, Inc, who paid for the services provided by Prescott Medical Communications Group (Chicago, IL), but did not suggest the topic nor did they participate in the development of arguments presented in this paper.

References

- 1. Dzau VJ, Antman EM, Black HR, et al. The cardiovascular disease continuum validated: clinical evidence of improved patient outcomes: part II: clinical trial evidence (acute coronary syndromes through renal disease) and future directions. Circulation. 2006;114:2871–2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dzau VJ, Antman EM, Black HR, et al. The cardiovascular disease continuum validated: clinical evidence of improved patient outcomes: part I: pathophysiology and clinical trial evidence (risk factors through stable coronary artery disease). Circulation. 2006;114:2850–2870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sin DD, Man SF. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:8–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kado DM, Browner WS, Blackwell T, et al. Rate of bone loss is associated with mortality in older women: a prospective study. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:1974–1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lloyd‐Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:e46–e215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gabriel SE. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med. 2008;121(suppl 1):S9–S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Frishman WH. Β‐Adrenergic blockers: a 50‐year historical perspective. Am J Ther. 2008;15:565–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta‐analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. BMJ. 2009;338:b1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lindholm LH, Carlberg B, Samuelsson O. Should β blockers remain first choice in the treatment of primary hypertension? A meta‐analysis. Lancet. 2005;366:1545–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wiysonge CS, Bradley H, Mayosi BM, et al. Β‐blockers for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;1:CD002003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bangalore S, Sawhney S, Messerli FH. Relation of β‐blocker‐induced heart rate lowering and cardioprotection in hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1482–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pedersen ME, Cockcroft JR. The vasodilatory β‐blockers. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2007;9:269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cockcroft JR, Chowienczyk PJ, Brett SE, et al. Nebivolol vasodilates human forearm vasculature: evidence for an L‐arginine/NO‐dependent mechanism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;274:1067–1071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dessy C, Saliez J, Ghisdal P, et al. Endothelial β3‐adrenoreceptors mediate nitric oxide‐dependent vasorelaxation of coronary microvessels in response to the third‐generation beta‐blocker nebivolol. Circulation. 2005;112:1198–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mannino DM. COPD: epidemiology, prevalence, morbidity and mortality, and disease heterogeneity. Chest. 2002;121(suppl 5):121S–126S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, et al. International variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): a population‐based prevalence study. Lancet. 2007;370:741–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Halbert RJ, Natoli JL, Gano A, et al. Global burden of COPD: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:523–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, et al. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006;367:1747–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fabbri LM, Luppi F, Beghe B, Rabe KF. Complex chronic comorbidities of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:204–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hole DJ, Watt GC, Davey‐Smith G, et al. Impaired lung function and mortality risk in men and women: findings from the Renfrew and Paisley prospective population study. BMJ. 1996;313:711–715; discussion 715–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hospers JJ, Postma DS, Rijcken B, et al. Histamine airway hyper‐responsiveness and mortality from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cohort study. Lancet. 2000;356:1313–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schunemann HJ, Dorn J, Grant BJ, et al. Pulmonary function is a long‐term predictor of mortality in the general population: 29‐year follow‐up of the Buffalo Health Study. Chest. 2000;118:656–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Speizer FE, Fay ME, Dockery DW, Ferris BG Jr. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease mortality in six U.S. cities. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;2:S49–S55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tockman MS, Pearson JD, Fleg JL, Fleg JL Rapid decline in FEV1. A new risk factor for coronary heart disease mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;1:390–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Finkelstein J, Cha E, Scharf SM. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2009;4:337–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sabit R, Bolton CE, Edwards PH, et al. Arterial stiffness and osteoporosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:1259–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gan WQ, Man SF, Senthilselvan A, et al. Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and systemic inflammation: a systematic review and a meta‐analysis. Thorax. 2004;59:574–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barr RG, Mesia‐Vela S, Austin JH, et al. Impaired flow‐mediated dilation is associated with low pulmonary function and emphysema in ex‐smokers: the Emphysema and Cancer Action Project (EMCAP) Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:1200–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Laurent S, Cockcroft J, Van Bortel L, et al. Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2588–2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Stefanadis C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all‐cause mortality with arterial stiffness: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1318–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bolton CE, Cockcroft JR, Sabit R, et al. Lung function in mid‐life compared with later life is a stronger predictor of arterial stiffness in men: the Caerphilly Prospective Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:867–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jankowich MD, Taveira T, Wu WC. Decreased lung function is associated with increased arterial stiffness as measured by peripheral pulse pressure: data from NHANES III. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:614–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bolton CE, Cockcroft JR. Lung function and cardiovascular risk: a stiff challenge? Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rutten FH, Cramer MJ, Grobbee DE, et al. Unrecognized heart failure in elderly patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1887–1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cheriyan J, Wilkinson IB. Role of increased aortic stiffness in the pathogenesis of heart failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2007;4:121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sabit R, Bolton CE, Fraser AG, et al. Sub‐clinical left and right ventricular dysfunction in patients with COPD. Respir Med. 2010;104:1171–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Padeletti M, Jelic S, LeJemtel TH. Coexistent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure in the elderly. Int J Cardiol. 2008;125:209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sin DD, Man SF. Why are patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at increased risk of cardiovascular diseases? The potential role of systemic inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Circulation. 2003;107:1514–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sesso HD, Buring JE, Rifai N, et al. C‐reactive protein and the risk of developing hypertension. JAMA. 2003;290:2945–2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schillaci G, Pirro M, Gemelli F, et al. Increased C‐reactive protein concentrations in never‐treated hypertension: the role of systolic and pulse pressures. J Hypertens. 2003;21:1841–1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Blake GJ, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. Blood pressure, C‐reactive protein, and risk of future cardiovascular events. Circulation. 2003;108:2993–2999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Thorleifsson SJ, Margretardottir OB, Gudmundsson G, et al. Chronic airflow obstruction and markers of systemic inflammation: results from the BOLD study in Iceland. Respir Med. 2009;103:1548–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Joppa P, Petrasova D, Stancak B, Tkacova R. Systemic inflammation in patients with COPD and pulmonary hypertension. Chest 2006;130:326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Man SF, Connett JE, Anthonisen NR, et al. C‐reactive protein and mortality in mild to moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2006;61:849–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Margretardottir OB, Thorleifsson SJ, Gudmundsson G, et al. Hypertension, systemic inflammation and body weight in relation to lung function impairment‐an epidemiological study. COPD. 2009;6:250–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fabbri LM, Rabe KF. From COPD to chronic systemic inflammatory syndrome? Lancet. 2007;370:797–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Coulson JM, Rudd JH, Duckers JM, et al. Excessive aortic inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an 18F‐FDG PET pilot study. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1357–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sabit R, Shale DJ. Vascular structure and function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a chicken and egg issue? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:1175–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mannino DM, Thorn D, Swensen A, Holguin F. Prevalence and outcomes of diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:962–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mills NL, Miller JJ, Anand A, et al. Increased arterial stiffness in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a mechanism for increased cardiovascular risk. Thorax. 2008;63:306–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cockcroft JR. Exploring vascular benefits of endothelium‐derived nitric oxide. Am J Hypertens. 2005;2:177S–183S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Eickhoff P, Valipour A, Kiss D, et al. Determinants of systemic vascular function in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:1211–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Moro L, Pedone C, Scarlata S, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Angiology. 2008;59:357–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ashrafian H, Violaris AG. Β‐blocker therapy of cardiovascular diseases in patients with bronchial asthma or COPD: the pro viewpoint. Prim Care Respir J. 2005;14:236–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Salpeter S, Ormiston T, Salpeter E. Cardioselective β‐blockers for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4):CD003566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mason RP, Cockcroft JR. Targeting nitric oxide with drug therapy. J Clin Hypertens. 2006;8(suppl 12):40–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lee TA, Pickard AS, Au DH, et al. Risk for death associated with medications for recently diagnosed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:380–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rizos EC, Agouridis AP, Elisaf MS. The effect of statin therapy on arterial stiffness by measuring pulse wave velocity: a systematic review. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2010;8:638–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Takami T, Shigemasa M. Efficacy of various antihypertensive agents as evaluated by indices of vascular stiffness in elderly hypertensive patients. Hypertens Res. 2003;26:609–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mancini GB, Etminan M, Zhang B, et al. Reduction of morbidity and mortality by statins, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2554–2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Münzel T, Gori T. Nebivolol: the somewhat‐different β‐adrenergic receptor blocker. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1491–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wolf SC, Sauter G, Preyer M, et al. Influence of nebivolol and metoprolol on inflammatory mediators in human coronary endothelial or smooth muscle cells. Effects on neointima formation after balloon denudation in carotid arteries of rats treated with nebivolol. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2007;4:129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mason RP, Kalinowski L, Jacob RF, et al. Nebivolol reduces nitroxidative stress and restores nitric oxide bioavailability in endothelium of black Americans. Circulation. 2005;112:3795–3801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tzemos N, Lim PO, MacDonald TM. Nebivolol reverses endothelial dysfunction in essential hypertension: a randomized, double‐blind, crossover study. Circulation. 2001;104:511–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. McEniery CM, Schmitt M, Qasem A, et al. Nebivolol increases arterial distensibility in vivo. Hypertension. 2004;44:305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Dal Negro R. Pulmonary effects of nebivolol. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;3:329–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Cazzola M, Matera MG, Ruggeri P, et al. Comparative effects of a two‐week treatment with nebivolol and nifedipine in hypertensive patients suffering from COPD. Respiration. 2004;71:159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Iakushin SS, Okorokov VG, Liferov RA, et al. [Assessment of safety and antihypertensive efficacy of a cardioselective β‐blocker nebivolol in patients with hypertension and concomitant chronic obstructive bronchitis]. Kardiologiia. 2002;42:36–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Matthys H, Giebelhaus V, Von Fallois J. [Nebivolol (nebilet) a β blocker of the third generation – also for patients with obstructive lung diseases?]. Z Kardiol. 2001;90:760–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kotlyar E, Keogh AM, Macdonald PS, et al. Tolerability of carvedilol in patients with heart failure and concomitant chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2002;21:1290–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Jabbour A, Macdonald PS, Keogh AM, et al. Differences between β‐blockers in patients with chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized crossover trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1780–1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Au DH, Bryson CL, Fan VS, et al. Β‐blockers as single‐agent therapy for hypertension and the risk of mortality among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 2004;117:925–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Rutten FH, Zuithoff NP, Hak E, et al. Β‐blockers may reduce mortality and risk of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:880–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Short PM, Lipworth SI, Elder DH, et al. Effect of β blockers in treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2011;342:d2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Rabe KF. Update on roflumilast, a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163:53–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Rennard SI, Fogarty C, Kelsen S, et al. The safety and efficacy of infliximab in moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:926–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases . Osteoporosis Review. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Compston J. Osteoporosis: social and economic impact. Radiol Clin North Am. 2010;48:477–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Cappuccio FP, Meilahn E, Zmuda JM, Cauley JA. High blood pressure and bone‐mineral loss in elderly white women: a prospective study. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Lancet. 1999;354:971–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Farhat GN, Newman AB, Sutton‐Tyrrell K, et al. The association of bone mineral density measures with incident cardiovascular disease in older adults. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:999–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Tanko LB, Bagger YZ, Christiansen C. Low bone mineral density in the hip as a marker of advanced atherosclerosis in elderly women. Calcif Tissue Int. 2003;73:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Choi SH, An JH, Lim S, et al. Lower bone mineral density is associated with higher coronary calcification and coronary plaque burdens by multidetector row coronary computed tomography in pre‐ and postmenopausal women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2009;71:644–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Mikumo M, Okano H, Yoshikata R, et al. Association between lumbar bone mineral density and vascular stiffness as assessed by pulse wave velocity in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Metab. 2009;27:89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Blaha MJ, Budoff MJ, Rivera JJ, et al. Relationship of carotid distensibility and thoracic aorta calcification: multi‐ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Hypertension. 2009;54:1408–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. McEniery CM, McDonnell BJ, So A, et al. Aortic calcification is associated with aortic stiffness and isolated systolic hypertension in healthy individuals. Hypertension. 2009;53:524–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Hjortnaes J, Butcher J, Figueiredo JL, et al. Arterial and aortic valve calcification inversely correlates with osteoporotic bone remodelling: a role for inflammation. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1975–1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Bagger YZ, Tanko LB, Alexandersen P, et al. Radiographic measure of aorta calcification is a site‐specific predictor of bone loss and fracture risk at the hip. J Intern Med. 2006;259:598–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Kim SH, Kim YM, Cho MA, et al. Echogenic carotid artery plaques are associated with vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with low bone mass. Calcif Tissue Int. 2008;82:411–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Watson KE, Bostrom K, Ravindranath R, et al. TGF‐β 1 and 25‐hydroxycholesterol stimulate osteoblast‐like vascular cells to calcify. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:2106–2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Parhami F, Bostrom K, Watson K, Demer LL. Role of molecular regulation in vascular calcification. J Atheroscler Thromb. 1996;3:90–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Dhore CR, Cleutjens JP, Lutgens E, et al. Differential expression of bone matrix regulatory proteins in human atherosclerotic plaques. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1998–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;420:868–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Tintut Y, Patel J, Territo M, et al. Monocyte/macrophage regulation of vascular calcification in vitro. Circulation. 2002;105:650–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Ding C, Parameswaran V, Udayan R, et al. Circulating levels of inflammatory markers predict change in bone mineral density and resorption in older adults: a longitudinal study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1952–1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Lacativa PG, Farias ML. Osteoporosis and inflammation. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2010;54:123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Ferguson GT, Calverley PM, Anderson JA, et al. Prevalence and progression of osteoporosis in patients with COPD: results from the TOwards a Revolution in COPD Health study. Chest. 2009;136:1456–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Evans DM, Ralston SH. Nitric oxide and bone. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11:300–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Wimalawansa S, Chapa T, Fang L, et al. Frequency‐dependent effect of nitric oxide donor nitroglycerin on bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:1119–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Wimalawansa SJ. Nitric oxide and bone. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1192:391–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Ducy P, Amling M, Takeda S, et al. Leptin inhibits bone formation through a hypothalamic relay: a central control of bone mass. Cell. 2000;100:197–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Elefteriou F, Ahn JD, Takeda S, et al. Leptin regulation of bone resorption by the sympathetic nervous system and CART. Nature. 2005;434:514–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Takeda S, Elefteriou F, Levasseur R, et al. Leptin regulates bone formation via the sympathetic nervous system. Cell. 2002;111:305–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Ladage D, Brixius K, Hoyer H, et al. Mechanisms underlying nebivolol‐induced endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;33:720–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Samuels A, Perry MJ, Gibson RL, et al. Role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in estrogen‐induced osteogenesis. Bone. 2001;29:24–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Dogru MT, Aydos TR, Aktuna Z, et al. The effects of β‐blockers on endothelial nitric oxide synthase immunoreactivity in the rat corpus cavernosum. Urology. 2010;75:589–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Fu GS, Huang H, Chen F, et al. Carvedilol ameliorates endothelial dysfunction in streptozotocin‐induced diabetic rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;567:223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Schlienger RG, Kraenzlin ME, Jick SS, Meier CR. Use of β‐blockers and risk of fractures. JAMA. 2004;292:1326–1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Wiens M, Etminan M, Gill SS, et al. Effects of antihypertensive drug treatments on fracture outcomes: a meta‐analysis of observational studies. J Intern Med. 2006;260:350–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Yang S, Nguyen ND, Center JR, et al. Association between β‐blocker use and fracture risk: the Dubbo Osteoporosis Epidemiology Study. Bone. 2011;48:451–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Cepeda MS. The use of propensity scores in pharmacoepidemiologic research. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2000;9:103–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Joffe MM, Rosenbaum PR. Invited commentary: propensity scores. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:327–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Amoh‐Tonto CA, Malik AR, Kondragunta V, et al. Brachial‐ankle pulse wave velocity is associated with walking distance in patients referred for peripheral arterial disease evaluation. Atherosclerosis. 2009;206:173–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Hirsch AT, Criqui MH, Treat‐Jacobson D, et al. Peripheral arterial disease detection, awareness, and treatment in primary care. JAMA. 2001;286:1317–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Cheng KS, Tiwari A, Baker CR, et al. Impaired carotid and femoral viscoelastic properties and elevated intima‐media thickness in peripheral vascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 2002;164:113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Tai NR, Giudiceandrea A, Salacinski HJ, et al. In vivo femoropopliteal arterial wall compliance in subjects with and without lower limb vascular disease. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30:936–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Mitchell GF, Vita JA, Larson MG, et al. Cross‐sectional relations of peripheral microvascular function, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and aortic stiffness: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2005;112:3722–3728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Safar ME. Arterial stiffness and peripheral arterial disease. Adv Cardiol. 2007;44:199–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Cooke JP, Wilson AM. Biomarkers of peripheral arterial disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2117–2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. De Haro J, Acin F, Lopez‐Quintana A, et al. Direct association between C‐reactive protein serum levels and endothelial dysfunction in patients with claudication. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35:480–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. De Haro J, Acin F, Medina FJ, et al. Relationship between the plasma concentration of C‐reactive protein and severity of peripheral arterial disease. Clin Med Cardiol. 2009;3:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Khawaja FJ, Kullo IJ. Novel markers of peripheral arterial disease. Vasc Med. 2009;14:381–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Cambou JP, Aboyans V, Constans J, et al. Characteristics and outcome of patients hospitalised for lower extremity peripheral artery disease in France: the COPART Registry. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;39:577–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Sleszycka J, Wozniak K, Banaszek M, et al. [Prevalence and difficulties in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease diagnosis in patients suffering from severe peripheral arterial disease]. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2009;27:92–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. De Lucas‐Ramos P, Izquierdo‐Alonso JL, Rodriguez‐Gonzalez Moro JM, et al. [Cardiovascular risk factors in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results of the ARCE study]. Arch Bronconeumol. 2008;44:233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Castagna O, Boussuges A, Nussbaum E, et al. Peripheral arterial disease: an underestimated aetiology of exercise intolerance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2008;15:270–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Mangiafico RA, Russo E, Riccobene S, et al. Increased prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in osteoporotic postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Metab. 2006;24:125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Safar ME, Priollet P, Luizy F, et al. Peripheral arterial disease and isolated systolic hypertension: the ATTEST study. J Hum Hypertens. 2009;23:182–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Ostchega Y, Paulose‐Ram R, Dillon CF, et al. Prevalence of peripheral arterial disease and risk factors in persons aged 60 and older: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2004. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:583–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Paravastu SC, Mendonca D, Da Silva A. Β blockers for peripheral arterial disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD005508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Cazzola M, Bettoncelli G, Sessa E, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration. 2010;80:112–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Carbone L, Buzkova P, Fink HA, et al. Hip fractures and heart failure: findings from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Winkel TA, Hoeks SE, Schouten O, et al. Prognosis of atrial fibrillation in patients with symptomatic peripheral arterial disease: data from the REduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health (REACH) Registry. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;40:9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Flather MD, Shibata MC, Coats AJ, et al. Randomized trial to determine the effect of nebivolol on mortality and cardiovascular hospital admission in elderly patients with heart failure (SENIORS). Eur Heart J. 2005;26:215–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Ashley C, Burton D, Sverrisdottir YB, et al. Firing probability and mean firing rates of human muscle vasoconstrictor neurones are elevated during chronic asphyxia. J Physiol. 2010;588:701–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Rahman I, Adcock IM. Oxidative stress and redox regulation of lung inflammation in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:219–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Basu S, Michaelsson K, Olofsson H, et al. Association between oxidative stress and bone mineral density. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;288:275–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]