Abstract

This public mental health study highlights the interactions among social determinants and resilience on mental health, PTSD and acculturation among Iraqi refugees in Sweden 2012-2013.

Objectives: The study aims to understand participants' health, resilience and acculturation, paying specific attention to gender differences.

Design: The study, using a convenience sampling survey design (N = 4010, 53.2% men), included measures on social determinants, general health, coping, CD-RISC, selected questions from the EMIC, PC-PTSD, and acculturation.

Results: Gender differences and reported differences between life experiences in Iraq and Sweden were strong. In Sweden, religious activity was more widespread among women, whereas activity reflecting religion and spirituality as a coping mechanism decreased significantly among men. A sense of belonging both to a Swedish and an Iraqi ethnic identity was frequent. Positive self-evaluation in personal and social areas and goals in life was strong. The strongest perceived source of social support was from parents and siblings, while support from authorities generally was perceived as low. Self-rated health was high and the incidence of PTSD was low. A clear majority identified multiple social determinants contributing to mental health problems. Social or situational and emotional or developmental explanations were the most common. In general, resilience (as measured with CD-RISC) was low, with women's scores lower than that of men.

Conclusions: Vulnerability manifested itself in unemployment after a long period in Sweden, weak social networks outside the family, unsupportive authorities, gender differences in acculturation, and women showing more mental health problems. Though low socially determined personal scores of resilience were found, we also identified a strong level of resilience, when using a culture-sensitive approach and appraising resilience as expressed in coping, meaning, and goals in life. Clinicians need to be aware of the risks of poorer mental health among refugees in general and women in particular, although mental health problems should not be presumed in the individual patient. Instead clinicians need to find ways of exploring the cultural and social worlds and needs of refugee patients. Authorities need to address the described post-migration problems and unmet needs of social support, together comprising the well-established area of the social determinants of health.

Keywords: Iraqi, refugees, acculturation, mental health, trauma, social support, perceptions of illness, resilience

Introduction

In the Roadmap for Mental Health in Europe (ROAMER) article, on behalf of the ROAMER consortium funded by the European Commission, under the Seventh Framework Programme (Forsman et al., 2015), the following three priorities are particularly relevant (Forsman et al., 2015, p. 251–252):

Positive mental health and well-being and protective factors should be increasingly addressed in public mental health research.

Public mental health research should build on interdisciplinary perspectives in order to understand the complexity of mental health.

Studies should strengthen the understanding of the cultural factors (i.e., ethnicity, religion and value systems, and nationality) relevant for public mental health.

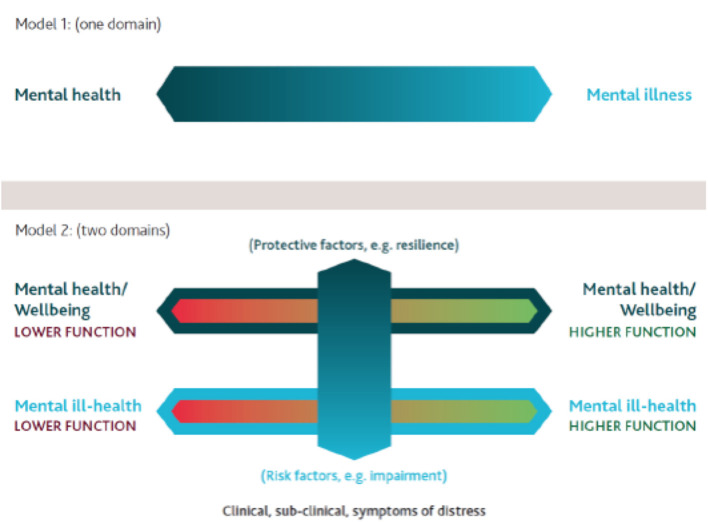

Following these recommendations, we in this study explore aspects of the migration process of Iraqi refugees who arrived in Sweden between 2010 and 2013. In accord with the ROAMER priorities, our aim was to elucidate enabling factors (social and cultural, and other resilience factors) as well as conceivable barriers to mental health and acculturation in this cohort. The study's theoretical foundation therefore rests on a two-domain model of mental health where mental ill-health and subjective well-being are distinct constructs (Patalay and Fitzsimons, 2016).

The two-domain model as depicted in Figure 1 permits a more complete understanding of the different domains of mental health (domain 1—mental health/mental illness, and domain 2—mental health/well-being) and focuses on the numerous interacting factors between them that can affect actual daily function. The model is fluid, and reflects the growing evidence of interaction between the two domains (Kalra et al., 2012; Patalay and Fitzsimons, 2016; DeMarinis and Boyd-MacMillan, 2019; Boyd-MacMillan and DeMarinis, 2020). Addressing the important critique that Betancourt and Khan (2008) raise that the focus on trauma alone has resulted in inadequate attention to factors associated with resilient mental health outcomes, our application of the two-domain model acknowledges the negative mental health consequences of war-related and other forms of violence and loss as well as other determinants, and allows for reflecting on multiple theoretical areas needed to investigate mental health.

Figure 1.

Two-domain-model of mental health. Modified from (Boyd-MacMillan and DeMarinis, 2020).

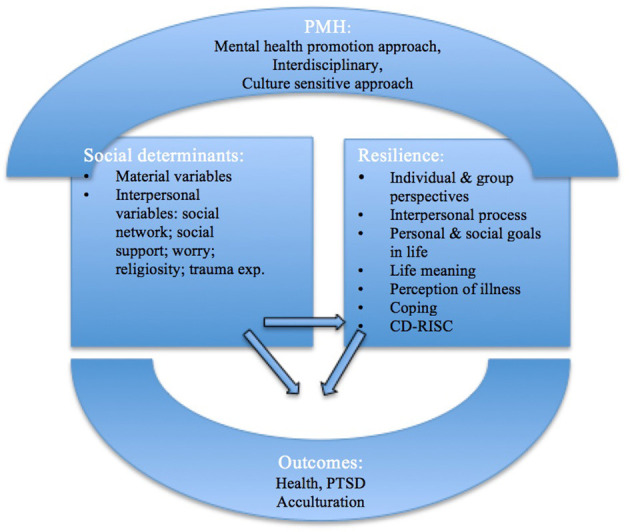

In Figure 2 we describe the theoretical framework used and the relationships between the theoretical perspectives included in this framework.

Figure 2.

Theoretical overview with a public mental health approach to social determinants, resilience and outcomes. Original figure developed by authors. PMH, Public Mental Health; CD-RISC, Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale; PTSD, Post-traumatic stress disorder.

Social Determinants of Health

Adverse social conditions, including poverty, unemployment, housing problems, gender-based discrimination, social stratification and unfairness, and lack of social support may lead to health inequity and hinder people from having “the freedom to lead flourishing lives” (Marmot, 2007). Thinking about the social realities of refugees, it is relevant to take into account stages of their resettlement: premigration, during migration, and post-migration. As seen in Figure 2, social determinants can be characterized as either material variables (a physically safe environment, housing, healthcare, education, economy, and policies) or interpersonal ones (e.g., a sense of cultural, ethnic, or religious belonging, social network and support, trauma experiences, discrimination, and social status) (Hynie, 2018; Cetrez et al., 2020b).

Material Variables

For decades, segments of the Iraqi population suffered from financial restraints, unemployment, internal displacement, conscriptions for war, lack of food and medicine, and destruction of healthcare infrastructure (Jamil et al., 2010; Warda et al., 2018).

Between 2000 and 2016 Sweden received a total of 90,217 Iraqi asylum seekers, 20,858 of whom arrived in 2015 (Migration Agency [Migrationsverket], 2017). A report on Swedish integration policies, practices, and experiences (Cetrez et al., 2020a) emphasizes recent drastic changes of legislative measures, including a shift of focus from integration to individual establishment. While newcomers are welcome to participate in different educational programs, segregation in housing has become a major challenge. In general, access to health care services is relatively unproblematic.

Interpersonal Variables

Earlier studies have found that the weakening of social networks and lack of social support affect the mental health and quality of life of refugees (Gorst-Unsworth and Goldenberg, 1998; Laban et al., 2005; Gerritsen et al., 2006; Sundvall et al., 2020). In a review of studies on resettled war refugees, the impact of low social support was especially noticeable in association with depression (Bogic et al., 2015). Tinghög et al. (2016) demonstrated a strong association between low social support and symptoms of anxiety and depression as well as low levels of well-being among refugees from Eritrea, Somalia, and Syria living in Sweden.

Refugees often report high levels of traumatic experiences in the premigration period. In a study on Iraqi male migrants to the UK 1990-93, Gorst-Unsworth and Goldenberg (1998) reported that 65% of these refugees had experienced torture during periods of detention. In a recent study of refugees in the USA, those from Iraq had often reported either having experienced torture, violence, or imprisonment themselves, or witnessed the torture or violence (Schlaudt et al., 2020).

Resilience

A public mental health promotion approach focuses on protective and salutogenic factors that contribute to resilience (DeMarinis, 2014). These social determinants operate in both pre- and post-migration contexts (Mawani, 2014). Resilience denotes the personal qualities that enable an individual to thrive in the face of adversity (Connor and Davidson, 2003); it is associated with improvements in both physical and mental health (Connor et al., 1999). Resilience may also be viewed as a measure of successful coping with stress (Connor and Davidson, 2003). Coping can be defined as a process through which individuals attempt to understand and deal with important demands in their lives (Ganzevoort, 1998), or as a search for meaning in difficult times (Pargament, 1997). Meaning-making is a general human characteristic, and existential meaning refers to an individual's or a group's most essential meaning-making activity (DeMarinis, 2014). A concept related to resilience, ‘hardiness’ has been used as an index of mental health (Ramaniah et al., 1999). Both hardiness and resilience have been shown to protect against developing chronic post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after traumatic experiences (Waysman et al., 2001).

A person's resilience is, however, not only an individual process but also an interpersonal one, that is, a human resource that develops and thrives in a culturally defined group- and community context (Kirmayer et al., 2011). Ungar's (2008) definition of resilience includes the processes of social navigation and negotiation:

In the context of exposure to significant adversity, whether psychological, environmental, or both, resilience is both the capacity of individuals to navigate their way to health-sustaining resources, including opportunities to experience feelings of well-being, and a condition of the individual's family, community and culture to provide these health resources and experiences in culturally meaningful ways (p. 225).

Further, Mawani (2014) showed an association between religious/spiritual support and positive health outcomes, indicating that refugees prefer finding support within their own group for reasons of language, connection, and trust. According to Walsh (2006), both family and community provide supportive belief systems, organizational patterns, and communication processes; your own culture is at the same time a source of social support and of social pressure. Additionally, Panter-Brick and Eggerman (2012) underscored that an ecological approach to resilience indicates “a sense of meaning-making that orders the world and gives coherence to the past, present, and the future” (p. 385).

Kirmayer et al. (2011) objected to resilience research merely focusing on the inverse of risk factors and favored an approach to resilience as a dynamic process of adaptation and transformation. Taking this point to heart, we include a focus on the refugee's perception of illness and help-seeking behavior.

Following a society's value system adds to a person's social resilience in that societal context. In contemporary Sweden, gender equality, secular-rational worldviews, and a high esteem of self-expression are predominant values (Welzel, 2013; DeMarinis, 2014). If a minority group or individuals in such groups espouse and practice a value system at odds with the larger societal system, then drops in both individual and social resilience levels can occur.

Outcomes

Health

A study of self-perceived health among newly arrived Iraqis to Sweden 2007–2008 showed that 55% rated their general health as good or very good, with no significant difference between genders, age groups, or individuals with different levels of education (Sundell Lecerof, 2010). However, 16% of the studied migrants reported poor or very poor general health and 37% reported reduced mental well-being, both rates twice as high as that in the general Swedish population; 29% responded that they often felt stressed in everyday life. In a study on Iraqi male refugees in the UK by Gorst-Unsworth and Goldenberg (1998), 10.7% of the participants evinced PTSD. Taylor et al. (2014) reported chronic health conditions, emotional stress, and depression among half of an Iraqi refugee sample residing in the U.S. (N = 366) 2007–2010. In a mental health screening of 8,149 refugees of different nationalities in Kentucky, 22.13% screened positively for emotional distress on Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15), predicting depression, anxiety, and PTSD. Almost half of the Iraqi participants had positive scores; higher age and females predicted positive scores. A systematic literature review by Bogic et al. (2015) showed that higher exposure to traumatic experiences and post-migration stress were the most common factors consistently associated with higher rates of mental disorders in war-refugees.

In a meta-analysis of 20 studies, Fazel et al. (2005) found that about 10% of adult refugees in Western countries suffer from PTSD. The prevalence of PTSD specifically among Iraqi refugees in different countries, however, varies strongly, between 14% (Kira et al., 2009), 28% (Jamil et al., 2005), 31% (Taylor et al., 2014), 37% (Söndergaard et al., 2004), 43% (Craig et al., 2006), and 83% (Daud et al., 2008). Kira et al. (2009) found that PTSD was more prevalent in women than in men and in individuals who were married, divorced, widowed, or adolescents than in those who were single or temporarily separated. The same study showed a high prevalence of PTSD among the elderly (70+) and people aged 41–50 as well as an association between PTSD and length of stay in the new country, and with low education.

Several studies demonstrate an association between post-migration experiences, for example, a long period as an asylum seeker (Laban et al., 2004) or being in detention during the asylum process (Steel et al., 2006) and high scores of PTSD and other mental disorders. In a study on Iraqi-Mandaean refugees in Australia by Nickerson et al. (2009), a reversed sequence of determination was noted: PTSD predicted a subsequent fear of cultural extinction.

Acculturation

Acculturation refers to the acquisition of a second culture and the process of perceiving new practices and behaviors in the encounter between two cultural groups (Rudmin, 2009), with outcomes such as integration, separation, assimilation and marginalization (Berry, 2006). Acculturation includes coping with social and psychological conflicts (intrapsychic or interpersonal), e.g., when cultural norms clash, or when gender roles and relationships are renegotiated and women take novel positions of power in their family (Suarez-Orozco, 2000; Nelson et al., 2016). Rudmin (2009) documented two critical social determinants of acculturation: the migrant's socioeconomic situation and his or her perception of discrimination in society.

An important field of acculturation research relates education and language skills to measures of health, e.g., experienced stress and depression (Wrobel et al., 2009; Hahn and Truman, 2015). Van Tubergen (2010) elucidated the links between post-migration language acquisition and pre-migration factors such as schooling, age at the time of migration, geographic mobility, time spent in refugee reception facilities, completion of integration courses and other education, intention to remain in the host country, and complex health problems. Other research has demonstrated that negative health outcomes are linked to refugee- or temporary resident status (Steel et al., 2006), pre-migration traumatic events and continuous high levels of stress (Rian and Hodge, 2010), psychopathology, and post-migration living problems (Laban et al., 2005), abuse (Padela and Heisler, 2010), and experiences of discrimination, detention, dispersal, destitution, delayed decisions on asylum, denial of the right to work, or denial to healthcare—the seven D's (McKenzie et al., 2014).

Studies on identity and acculturation, including that of Iraqi minority subgroups (Cetrez, 2005, 2011, 2015) cautions against a simplistic understanding of belonging as an either-or identification with a given culture. Allegiance to multiple groups is promoted by what Collie et al. (2010) describe as a mindful, strategic, and contextual identity negotiation, as is the co-existence within one person of different ethnic identities (Sirina et al., 2008).

Aim

The aim of this study was to explore the social and psychological determinants of health, especially mental health, and resilience and acculturation outcomes in a population of resettled Iraqi refugees who arrived in Sweden in the years 2000-2013. We also wished to investigate gender differences and situate our findings in the Swedish societal context.

Method

Sample

The studied group of refugees was a convenience sample, recruited through written information material, key persons in community networks, associations, organizations, schools, and workplaces. Our inclusion criteria were being Iraqi, having moved to Sweden between 2000 and 2013, and residing in the cities of Stockholm, Uppsala or Södertälje. Table 1 presents the sample, 410 individuals of whom 218 were men (53.2%) and 192 women (46.8%). The women (M = 34.27, SD = 14.27) were significantly younger than the men (M = 39.98, SD = 16.14) (p < 0.001). Equal fractions of the respondents (33–34%) resided in each of the three cities.

Table 1.

Frequency and percentage for age, residence, and arrival, by gender.

| Men (%) | Women (%) | Total (%) | Missing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall sample | 218 (53.2) | 192 (46.8) | 410 | |

| Age group*** | 0 | |||

| 18–24 | 45 (20.6) | 66 (34.4) | 111 (27.1) | |

| 25–34 | 54 (24.8) | 53 (27.6) | 107 (26.1) | |

| 35–47 | 51 (23.4) | 36 (18.8) | 87 (21.2) | |

| 48+ | 68 (31.2) | 37 (19.3) | 105 (25.6) | |

| Current city of residence | 0 | |||

| Södertälje | 79 (36.2) | 59 (30.7) | 138 (33.7) | |

| Uppsala | 66 (30.3) | 71 (37) | 137 (33.4) | |

| Stockholm | 73 (33.5) | 62 (32.3) | 135 (32.9) | |

| Median year of arrival in Sweden | 2006 | 2006 | 2006 | 0 |

Chi-square tests for gender differences,

p < 0.01.

Instruments

The survey comprised items linked to the outlined theoretical themes. To explore the material social determinants, we included items on education, employment, economy, and physical safety. For the interpersonal variables, we included items on Swedish language proficiency, aspects of religion, and social support (emotional, concrete, informational, or spiritual) (Tracy and Whittaker, 1990; Balboni et al., 2007), and trauma experience. There were also items on everyday worries, both in Iraq and in Sweden. To document individual and cultural dimensions of resilience we included items linked to meaning of life, life goals, coping, and perceptions of illness (the latter from the Explanatory Model Interview Catalog, EMIC, Weiss, 1997). Resilience was also gauged with items from The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC 2) (Davidson, 2018, Vaishnavi et al., 2007). To evaluate mental-health, we included items on self-perceived health from the PC-PTSD screen (Prins et al., 2003). Acculturation was explored through items on identity (Cetrez, 2005), in addition to questions about living conditions in Iraq, compared to Sweden (see Appendix for the full questionnaire).

Procedure

The questionnaire was pretested (focusing on concepts, scales, language, and sensitivity, and refined/shortened accordingly) with different subgroups of respondents: two female and two male representatives from each of the three main religious denominations—Christian, Muslim, and Mandaean (in total 12 persons). Surveys were conducted in Arabic, English or Swedish, depending on the preference of the participants. It took on the average 30–40 min to complete the survey, but longer, up to 90 min, for individuals who needed help in reading and writing. Although designed as a self-administered questionnaire, most of the surveys were filled out in the presence of an Arabic-speaking research assistant (who provided language support). The setting for filling in the questionnaire was at the choice of the study person, for example, at school, work, cafés, and similar.

Data Analyses

The survey study data were analyzed with SPSS (version 27), limited to descriptive analyses using gender and country as independent variables.

Ethical Considerations

Participants were informed of the availability, through our auspices, of a psychiatric consultant, if needed. An interpreter would also be available as needed. Ethical approval was granted by the Uppsala Regional Ethical Review Board (reg. no. Dnr 2011/394).

Results

Social Determinants

As shown in Table 2, the respondents were mostly married or in a partnered relationship (59.6%), with two-fifths having children who lived at home. A majority (55.4% of the total sample) had a university degree. In this subgroup two-thirds had completed their education in Iraq, a third had done so in Sweden. The majority of the total sample (75.9%) had an occupation of some sort (including unpaid work). The rate of unemployment was significantly higher among men than women (see Table 2). Of those who were unemployed, two-thirds received support from municipal social services, and a tenth received government benefits. During the last 12 months, two-fifths of the unemployed had had difficulties in making ends meet: paying bills for food, rent, etc. A majority of the respondents reported their competency in Swedish as strong. Although most of them did not speak Swedish at home, they spoke and wrote Swedish at work, on the internet, and with friends.

Table 2.

Social determinants, by gender (N = 410).

| Men | Women | Total | Missing | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Relationship status: in a relationship* | 138 | 63.6 | 105 | 45 | 243 | 59.6 | 2 |

| Children at home* | 96 | 44.04 | 74 | 38.54 | 170 | 41.46 | 0 |

| Education: University | 118 | 54.38 | 108 | 56.54 | 226 | 55.39 | 2 |

| Unemployed** | 60 | 28.4 | 36 | 19.3 | 96 | 24.1 | 12 |

| Economic difficulty** | 101 | 46.3 | 69 | 36.1 | 170 | 41.6 | 1 |

| Strong Swedish proficiency | 138 | 63.9 | 129 | 67.9 | 267 | 65.8 | 4 |

| Use Swedish at home | 34 | 15.96 | 37 | 20 | 71 | 17.84 | 12 |

| Use Swedish at work | 139 | 88.54 | 128 | 90.14 | 267 | 89.3 | 111 |

| Use Swedish in free time (friends, Internet, other free time) | 157 | 76.96 | 150 | 81.52 | 307 | 79.12 | 22 |

Chi-square tests for gender differences,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.1.

Table 3 covers life meaning, coping, and worries, both in Iraq and Sweden. Most respondents reported that worrying about family, friends and safety was the worst and that they were relieved when these concerns subsided. This experience of positive change was significant both for men and women. Yet, worries about work and studies significantly increased over time for both men and women. Overall, significant gender differences were present in connection with worrying about family: men tended to worry more than women (in Iraq: p = 0.042, in Sweden: p = 0.065). A majority of the total sample (app. 91%) felt either “very” (69%) or “somewhat” (22%) safe at home as well in their neighborhood (86%).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics for life meaning, coping and worries, by gender and by country.

| Men | Women | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iraq | Sweden | Iraq | Sweden | |||||||||||

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | M diff | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | M diff. | |

| How much did/does … help you to make sense/give your life meaning during your most stable period in Iraq or now in Sweden? | ||||||||||||||

| Family | 206 | 9.10 | 2.00 | 194 | 9.11 | 1.48 | −0.01 | 182 | 9.40 | 1.43 | 179 | 9.21 | 1.57 | 0.19*** |

| Friends | 174 | 7.49 | 2.46 | 170 | 7.27 | 2.47 | 0.22 | 147 | 7.22 | 2.62 | 161 | 7.66 | 2.48 | −0.44 |

| Religion & spirituality | 168 | 7.31 | 3.06 | 159 | 7.22 | 3.13 | 0.09 | 151 | 8.02 | 2.56 | 151 | 8.07 | 2.63 | −0.05 |

| Work & school | 163 | 7.67 | 2.53 | 161 | 7.54 | 2.59 | 0.13 | 151 | 8.15 | 2.32 | 157 | 8.10 | 2.51 | 0.05 |

| To what extent did/does … help you in coping with any difficult situation you are facing during your most stable period in Iraq or now in Sweden? | ||||||||||||||

| Family | 191 | 9.47 | 1.26 | 190 | 9.07 | 1.94 | 0.40** | 172 | 9.41 | 1.42 | 176 | 9.30 | 1.44 | 0.11 |

| Friends | 161 | 7.71 | 2.23 | 166 | 7.43 | 2.56 | 0.28 | 134 | 7.13 | 2.77 | 152 | 7.49 | 2.57 | −0.37 |

| Religion & spirituality | 150 | 7.66 | 2.77 | 153 | 7.22 | 3.02 | 0.44* | 137 | 8.01 | 2.67 | 146 | 8.16 | 2.62 | −0.16 |

| Work & school | 147 | 7.31 | 2.57 | 152 | 6.97 | 2.66 | 0.34 | 130 | 7.06 | 2.69 | 146 | 7.45 | 2.68 | −0.38* |

| Being out in nature | 127 | 6.51 | 3.09 | 152 | 8.01 | 2.30 | −1.49*** | 118 | 6.00 | 3.32 | 153 | 8.18 | 2.35 | −2.18*** |

| What worried/worries you most, during your most difficult time in Iraq and now in Sweden | ||||||||||||||

| Family | 139 | 8.73 | 2.46 | 155 | 7.61 | 3.12 | 1.12*** | 125 | 8.02 | 3.17 | 130 | 6.86 | 3.66 | 1.15*** |

| Friends | 124 | 6.43 | 2.72 | 127 | 5.89 | 3.02 | 0.54*** | 104 | 6.11 | 2.95 | 115 | 5.34 | 3.30 | 0.77* |

| Work & school | 115 | 6.77 | 3.00 | 153 | 7.67 | 2.84 | −0.91** | 110 | 6.65 | 3.07 | 149 | 7.50 | 2.99 | −0.85* |

| Safety | 183 | 8.95 | 2.40 | 106 | 5.13 | 3.40 | 3.82** | 161 | 8.89 | 2.30 | 115 | 4.89 | 3.45 | 4.01*** |

Chi–square tests for country differences,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.1.

Scale from 1 (Not at all) to 10 (Very much).

Table 4 presents social support, with the responses categorized according to type of support: emotional, concrete, informational, and spiritual. Parents and siblings were the most important sources of support. This was particularly true for women. Men relied significantly more often than women on sources outside the family for concrete support (18.4%, from Iraqis living in Sweden, for men vs. 10.9% for women) and informational support (7.7%, from members of associations and churches, for men, vs. 1.6% for women).

Table 4.

Frequency and percentage for social support, by gender, in Sweden.

| Male | Female | Total | Missing | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Help from … | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Emotional support | 20 | ||||||

| Partner/children | 112 | 54.1 | 86 | 47 | 198 | 50.8 | |

| Parents/siblings*** | 102 | 49.3 | 123 | 67.2 | 225 | 57.7 | |

| Other relatives | 29 | 14 | 26 | 14.2 | 55 | 14.1 | |

| God | 59 | 28.5 | 61 | 33.3 | 120 | 30.8 | |

| No one | 17 | 8.2 | 7 | 3.8 | 24 | 6.2 | |

| Concrete support | 19 | ||||||

| Partner/children | 83 | 40.1 | 69 | 37.5 | 152 | 38.9 | |

| Parents/siblings *** | 99 | 47.8 | 112 | 60.9 | 211 | 54 | |

| Other relatives | 53 | 25.6 | 49 | 26.6 | 102 | 26.1 | |

| God | 9 | 4.3 | 4 | 2.2 | 13 | 3.3 | |

| People from Iraq in Sweden** | 38 | 18.4 | 20 | 10.9 | 58 | 14.8 | |

| No one** | 36 | 17.4 | 19 | 10.3 | 55 | 14.1 | |

| Informational support | 19 | ||||||

| Partner/children | 92 | 44.4 | 83 | 45.1 | 175 | 44.8 | |

| Parents/siblings** | 109 | 52.7 | 115 | 62.5 | 224 | 57.3 | |

| Other relatives | 35 | 16.9 | 32 | 17.4 | 67 | 17.1 | |

| God | 21 | 10.1 | 12 | 6.5 | 33 | 8.4 | |

| People from associations, churches*** | 16 | 7.7 | 3 | 1.6 | 19 | 4.9 | |

| No one | 34 | 16.4 | 30 | 16.3 | 64 | 16.4 | |

| Spiritual and religious support | 26 | ||||||

| Partner/children | 66 | 32.5 | 56 | 30.9 | 122 | 31.8 | |

| Parents/siblings*** | 70 | 34.5 | 93 | 51.4 | 163 | 42.4 | |

| Other relatives | 11 | 5.4 | 13 | 7.2 | 24 | 6.3 | |

| God | 48 | 23.6 | 36 | 19.9 | 84 | 21.9 | |

| No one | 20 | 9.9 | 13 | 7.2 | 33 | 8.6 | |

Chi–square tests for gender differences,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05.

Reporting those answers with responses of higher than 20% (0.2).

As to reported lack of support, 16.4% of the participants reported no support at all and an additional 14.1% no concrete support (Table 4). In the latter subgroup the gender difference was significant (17.4% for men, 10.3% for women). The level of perceived support from authorities (not in table) was even lower, ranging from 1.5% for emotional support to 6.1% for informational support.

In open responses, the respondents described the educational opportunities in Sweden as very positive, whereas work life was often regarded as discriminating and difficult. They generally appreciated the stability, equality, and justice they encountered in their new country. Concerning safety, one person said: “I feel much safer here than in Iraq. I have not been humiliated based on my Christian religion.” Another person was more ambivalent: “I feel safe, but sometimes I experience things that make me feel depressed, when I compare myself to a Sweden.” Some women reported facing discrimination for wearing a veil. Despite their perception of the situation in Sweden as better than in Iraq, and their attesting to feeling safe, some respondents were markedly concerned about physical security and criminality in society, which negatively affected their total sense of security.

Table 5 covers religiosity among participants. The results show significant gender differences, women responding that they were “very” religious more often than men (74% vs. 60.1%). As to religious activities such as fasting, a majority answered “sometimes” (26.1%) or “often” (33.3%), again with a significant difference between women and men. Another item, “how often do you pray?,” similarly showed a significant overrepresentation for women. A large majority, 341 persons (85.5%), of whom 181 were men and 160 women, responded that they belonged to a religion or religious denomination: Muslim (39.7%), 59 men and 76 women; Christian (33.2%), 62 men and 51 women; and Mandaean (26.8%), 57 men and 34 women. Asked about their image of God, a majority believed in a personal God (94.9%)−197 (52.8%) men and 176 (47.2%) women—whereas only 1,8% indicated adherence to what might be called an atheist orientation, explicitly excluding any belief in a personal God.

Table 5.

Frequency and percentage for religiosity, meaning, safety, and gender equality, by gender (N = 410).

| Men | Women | Total | Missing | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Belonging to a religion or religious denomination | 181 | 53.1 | 160 | 46.9 | 341 | 85.5 | 11 |

| How religious are you? Somewhat/a lot *** | 122 | 60.1 | 134 | 74 | 256 | 66.7 | 26 |

| Religious denomination**: Christian | 62 | 54.9 | 51 | 45.1 | 113 | 33.2 | 70 |

| Muslim | 59 | 43.7 | 76 | 56.3 | 135 | 39.7 | |

| Mandean | 57 | 62.6 | 34 | 37.4 | 91 | 26.8 | |

| I believe in personal god (opposite to belief in a spirit, or no belief at all) | 197 | 52.8 | 176 | 47.2 | 373 | 94.5 | 17 |

| Apart from weddings and funerals, about how often do you attend religious services/prayer services these days? Sometimes/often | 131 | 62.4 | 133 | 71.5 | 264 | 66.7 | 14 |

| How often do you fast? Sometimes/often *** | 102 | 48.6 | 135 | 71.4 | 237 | 59.4 | 11 |

| How often do you pray privately? Sometimes/often *** | 119 | 56.7 | 143 | 75.7 | 262 | 65.7 | 11 |

| How often, if at all, do you think about the meaning and purpose of life? Sometimes/often ** | 168 | 80 | 160 | 87.9 | 328 | 83.7 | 18 |

| Do you feel safe and secure at home? Pretty/very much | 197 | 90.8 | 175 | 92.1 | 372 | 91.4 | 3 |

| Do you feel safe and secure in your neighborhood? Pretty/very much | 182 | 85 | 166 | 87.8 | 348 | 86.4 | 7 |

| On the whole, men make better political leaders than women do. Disagree/strongly disagree | 137 | 63.4 | 133 | 69.9 | 270 | 66.3 | 3 |

| A university education is more important for a boy than for a girl. Disagree/strongly disagree | 189 | 87.9 | 178 | 92.7 | 367 | 90.2 | 3 |

Chi-square tests for gender differences,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05.

Table 6 presents traumatic experiences among the participants. There were significant differences between men and women, 63 (31.7%) vs. 41 (23.8%), respectively. While men more often responded that they had experienced traumatic situations, women reported having had more problems caused by the effects of traumas. The open-ended questions revealed that almost all trauma experiences (direct or indirect) were war-related, for example, explosions, public executions, kidnappings, threats, bombings, prison, assault, and torture. Other traumatic experiences related to traffic accidents, in- or outside of a war setting.

Table 6.

Frequency and percentage for general health, trauma and resilience, by gender.

| Men | Women | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Health | ||||||

| Excellent | 35 | 17.07 | 22 | 12.09 | 57 | 14.73 |

| Very good | 50 | 24.39 | 36 | 19.78 | 86 | 22.22 |

| Good | 76 | 37.07 | 70 | 38.46 | 146 | 37.73 |

| Fair | 37 | 18.05 | 47 | 25.82 | 84 | 21.71 |

| Poor | 7 | 3.41 | 7 | 3.85 | 14 | 3.62 |

| Trauma | ||||||

| Difficult situation* | 63 | 31.7 | 41 | 23.8 | 104 | 28 |

| PTSD | 21 | 10.2 | 22 | 12 | 43 | 11.1 |

| Resilience | ||||||

| CD-RISC 5+ | 106 | 53.8 | 78 | 45.6 | 184 | 50 |

| CD-RISC 6+* | 54 | 28.1 | 35 | 20.5 | 89 | 24.5 |

Chi-square tests for gender differences,

p < 0.1.

CD-RISC has cut-off levels at both 5+ and 6+.

Resilience

Table 7 presents self-assessment in personal and social areas and goals in life, both in Iraq and in Sweden. The ability to maintain a helpful social network deteriorated significantly after migration. The means and standard deviations for “socialization” and “network” in Iraq were M = 0.74, SD = 0.44 and M = 0.75, SD = 0.43, respectively, and in Sweden, M = 0.59, SD = 0.49 and M = 0.57, SD = 0.49, respectively. An overall significant ability to adapt to new situations was found nonetheless (Table 7). This effect was driven by a marked change among women as compared to men (p = 0.025). The women evaluated themselves as working more in Sweden than in Iraq, they worked both at home and were employed or pursued an education.

Table 7.

Frequency and percentage for self-assessment in personal and social areas and goals in life, by gender and by country (N = 410).

| Male | Female | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iraq | Sweden | Iraq-Swe Difference | Iraq | Sweden | Iraq-Swe Difference | |

| I (could) make friends | 91 | 91 | 85 | 84 | ||

| 71.7% | 63.6% | −8.0% | 65.4% | 59.6% | −5.8% | |

| I could socialize with others/It is easy to socialize with others | 101 | 89 | 108 | 77 | ||

| 76.5% | 62.2% | −14.3%** | 77.1% | 57.5% | −19.7%*** | |

| I was/am confident in handling challenges in life | 80 | 99 | 75 | 88 | ||

| 64.5% | 71.7% | 7.2% | 63.0% | 74.6% | 11.6% | |

| I was/am a hardworking person | 109 | 95 | 79 | 104 | ||

| 70.3% | 78.5% | 8.2% | 62.7% | 80.6% | 17.9%* | |

| I was/am goal–oriented | 81 | 93 | 79 | 92 | ||

| 69.8% | 75.0% | 5.2% | 65.3% | 74.8% | 9.5% | |

| I was/am a happy person | 82 | 90 | 79 | 75 | ||

| 59.0% | 70.3% | 11.3% | 62.2% | 65.8% | 3.6% | |

| I could/can adapt to new situations | 72 | 100 | 61 | 92 | ||

| 62.6% | 70.9% | 8.3% | 54.0% | 73.6% | 19.6%** | |

| I was/am a successful person | 105 | 72 | 82 | 73 | ||

| 77.2% | 69.2% | −8.0% | 72.6% | 68.9% | −3.7% | |

| I had/have a large and helpful network of people around me | 117 | 64 | 94 | 64 | ||

| 80.7% | 55.7% | −25.0%*** | 73.4% | 57.7% | −15.8%** | |

Chi-square tests for country differences.

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.1.

The respondents reported that the influence of family, relatives, friends, and neighbors both in Iraq and Sweden was “positive” or “very positive.” The largest negative differences in this regard between Iraq and Sweden concerned the change in the rates of “positive” and “very positive” influence of neighbors (reported in 84.3% cases in Iraq and 73.8% in Sweden). The smallest change was observed for the influence of family (from 97.4% in Iraq to 96.7% in Sweden).

Differences between men and women in experienced social support before and after migration were stark. For men there were no significant differences between living in Iraq or Sweden, neither in any of the items referring to family, friends, religion, and spirituality, nor in items about work and school in stable times (Table 3). There was, however, a significant decrease in the importance of family for females. Gender differences were also significant with regard to the impact of religion and spirituality (p = 0.026): women more often than men tended to rely on religion in making sense of life—in Iraq as well as in Sweden.

Many respondents described problems with health (42% of the total sample, of which almost two-thirds were men), finances (48%, of which more than half were men), and discrimination (31%, of which more than half were men) as barriers to achieving their goals in life. Men more often emphasized health issues than did women (p = 0.047).

Table 8 presents perceptions of illness. The personal explanations are categorized as social-situational, emotional-developmental, medical-biological, or religious-spiritual (cf. Estroff et al., 1991). Only 11.1% of the respondents identified explanations for mental health problems belonging to a single category.

Table 8.

Frequency and percentage for types of illness explanations for mental health problems, by gender.

| Men | Women | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Medical/clinical | 141 | 67.8 | 123 | 65.8 | 264 | 66.8 |

| Emotional/developmental | 177 | 85.1 | 165 | 88.2 | 342 | 86.6 |

| Social/situational | 184 | 88.5 | 165 | 88.2 | 349 | 88.4 |

| Religious/spiritual ** | 33 | 15.9 | 45 | 24.2 | 78 | 19.7 |

| Other cause | 10 | 4.8 | 5 | 2.7 | 15 | 3.8 |

Chi-square tests for gender differences,

p < 0.05.

Missing: 15.

Social and situational problems (in total 88.4%), foremost financial difficulties and unemployment (68.4%), were the most commonly given explanations of mental ill health (Table 8). Difficulties directly related to being a refugee were less common: 29.6% explained mental health problems by having been exposed to violence or threats, 24.1% by having had to flee from their country of origin, and 13.9% for persecution because of political or religious convictions.

Emotional and developmental explanations (86.6%) were almost as common as social explanations. Problems in close relationships, failures in life, and the death of or separation from a significant other were frequently mentioned. Death or separation was the most common explanations for women (52.4%), who significantly differed from the men in this respect (p = 0.002).

Medical or biological explanations of psychological problems or mental health issues were indicated by 66.8% of the respondents. Significantly more women than men believed that biochemical changes in the body caused mental health problems (p = 0.01). Religious or spiritual explanations were given by 19.8% of the respondents. Significantly more women than men explained mental health problems as caused by religious and spiritual forces.

Overall, particularly for women, religion was a significant supportive factor of coping with challenges of everyday life (see Table 3). Even though the support from the family had decreased after the migration to Sweden, the help from friends and religion increased. The most salient, though not statistically significant, positive change for women's social adaptation in the new country was, however, their utilization of support in school and in the workplace. Nature or being outdoors helped coping with difficult situations for both genders. There was a highly significant change in this respect, for both men and women, between Iraq and Sweden.

Table 6 presents results on self-perceived resilience as reflected on the CD-RISC scale. The median for the overall resilience score was 5.5, which is at the lower level of the scale. The number who met the criterion for resilience when using the cut-off 6+, was 54 (28.1%) for men, and 35 (20.5%) for women. A similar pattern was found using the cut-off 5+.

Health and Acculturation Outcomes

Almost 75% of the respondents evaluated their health as either “good,” “very good,” or “excellent” (Table 6). As is common for self-rated health, women (M = 2.9, SD = 1.04, where “excellent” was coded as 1 and “poor” as 5) evaluate their health slightly worse than men, though these differences are not significant (M = 2.66, SD = 1.07, p = 0.31). Additionally, 36.3% (71 men and 66 women) reported having experienced moderate to extreme pain that interfered with their work during the past 4 weeks. Problems with work or other regular daily activities caused by emotional problems (such as feeling depressed or anxious) were reported by 31.8% (61 men and 59 women) or to not carrying out work or other activities as diligently as usual by 27.5% (47 men and 52 women). Forty-three participants (11.1%, 21 men and 22 women) met the criteria for PTSD.

The ethnic labels used by the respondents were very diverse, frequently employing combinations of national and ethnic or religious subcategories, such as Iraqi- Arab-, or Suriani- (indicating Assyrian-Christian), Chaldean, and Kurdish. The majority of the respondents (both men and women, 68 and 63%, respectively) felt that they belonged both to their culture of origin as well as to Swedish culture and society; about 50% clarified that this double sense of self was an integrated (relatively conflict-free) experience. Yet at least half of the respondents (50.5%) reported having been treated unfairly based on their ethnic background or lack of language skills.

Acculturation outcomes were observed by asking about gender values, education, and family roles. A third of the sample responded that men make better political leaders than women (Table 5). As to the statement that a university education is more important for a boy than for a girl, about 10% agreed (checking either “strongly agree” or “agree,” with women showing stronger disagreement than men).

Finally, both men and women perceived that their role in the family had changed “somewhat” in Sweden compared to how it was in Iraq.

Discussion

Our study results with this group of Iraqi individuals, who had lived longer in their new country than subjects in comparable studies, illuminated the role played by social and psychological determinants of mental health, both pre- and post-migration, as well as the association of self-evaluated health, resilience, and benign acculturation processes among them. The widespread, dynamic bicultural, to varying degrees, sense of identity in our sample as in other immigrants should be acknowledged in integration policies by providing space for the realization and interaction of both the original and the new host culture. Similarly our finding that women showed greater adaptability and acculturation, yet at the same time lower mental health, which highlights the stress of the refugee's acculturation, deserves being taken to heart in integration policies. The family remained the most important source of social support in the new country, while support from other sources deteriorated.

A Lack of Social Support

A substantial proportion of the respondents did not receive either informational or emotional support from anyone. Combined with the fact that support from the authorities was generally perceived as very low, this finding indicates an unmet basic need and a challenge for Swedish society.

In earlier studies, other scales than those that we applied were used to rate social support, which makes comparisons difficult. We note, however, that in two studies social support was found to be low for both asylum seekers and refugees in general, with lower figures for asylum seekers (Gerritsen et al., 2006; Tinghög et al., 2016). The relatively high levels of perceived social support by the respondents in our study may, we contend, be explained by their relatively long time of residence in Sweden.

Aspects of Resilience

Measuring the level of resilience with the instrument CD-RISC, we found that the median resilience level among the Iraqi refugees was low, 5.5. Women scored lower than men, regardless of cut-off level, notwithstanding that they showed higher levels of self-efficacy and adaptation. There was an apparent discrepancy between the relatively low level of resilience measured by the two CD-RISC items and the high level of resilience grounded on measures of coping, meaning, and goals in life. This difference may reflect that the CD-RISC items reflect individual, intrapsychic qualities of resilience and low scores are coupled to mental ill-health concerns, whereas the coping-, meaning-, and life-goal items are grounded on interpersonal and social dimensions. Recognizing the interconnectedness of meaning and resilience (Panter-Brick and Eggerman, 2012), we like Ungar (2008) and Kirmayer et al. (2011), combined the two perspectives.

The low level of resilience measured with CD-RISC may nonetheless depend not only on psychological and individual network resources, but also on societal factors. Our results show well-known post-migration problems on that level, for example, unemployment, financial problems, reduced social networks, and discrimination. These findings point to the importance of addressing the socio-economic realities of refugees in order to strengthen their collective and individual resilience.

Cultural aspects of resilience were addressed by questions on perception of illness. That almost 90 % of the participants presented more than one “cause” of mental illness agrees with the findings of other research that show that personal explanations are not as fixed as might expected, but vary with context and cultural norms on how to communicate personal suffering (Lewis-Fernández et al., 2014). The majority of the respondents in or study gave social and situational explanations of mental illness. The finding that few respondents presented refugee-related explanations, such as traumatic experiences, concurs with the observation by Shannon et al. (2012) that a reason that their research subjects, refugee patients in primary care in the Midwest USA, avoided talking to general practitioners about trauma was that they didn't link trauma and ill-health. In all, our findings may also reflect the greater impact of general socioeconomic stressors. The results point to the need for clinicians to beware of stereotyping their patients' cultural perceptions and instead be prepared to explore them together with the patient.

Self-Perceived Health

The level of perceived health in this study is higher than in a comparable study in Sweden (Sundell Lecerof, 2010) as well as in a study on the Mandaean population in Australia (Nickerson et al., 2009). Our results also showed relatively low levels of PTSD (cf. Fazel et al., 2005). Most likely, PTSD in a population of migrants reflects its stratification in terms of subgroups such as war veterans and refugees of different ages, cultural backgrounds, and diagnoses.

Cultural differences within our sample and the fact that it was a convenience sample may constitute a threat to the validity of our findings. There may, for example, have been an unrecognized underlying reluctance among the participants to admit psychological symptoms or talk openly about traumatic experiences. These circumstances invite questions about host-country-specific factors, which would need to be investigated further.

Gender Differences in Acculturation

The women in our sample were significantly better adapted and evaluated themselves as more hard-working in Sweden than in Iraq. The burden of work responsibilities at home as well as in a workplace was experienced as positive by some but not all of the women. Different circumstances and concerns appeared to influence how the shift of family roles was perceived. The high degree of adaptability and self-efficacy of many women in our study may be understood against the backdrop of a pre-migration renegotiation of gender roles and the economic expansion in Iraq during the 1970s, during which period women were economically productive (Nelson et al., 2016). These observations on gender-specific patterns of adaptation are important for integration policies and programs, which need to be sensitive to differences in the acculturation process between women and men.

Similar to Miller and Hoffmann (1995) we found a significantly stronger religious commitment and activity among the studied women compared to the men. Other studies of immigrants have found different patterns: while religious affiliation is often higher among females, religious activity in terms of weekly attendance at religious services tends to be equally stable among men and women or show a higher rate among men (Finke and Stark, 1992; Van Tubergen, 2006). Men's attendance at religious activities or meetings is often attributed to the specific religious group they belong to, for example, Islam (Van Tubergen, 2006). In our study the local religious community appeared to be a welcoming context that positively affected the religious activity of newcomers, mainly Christian worshippers, both men and women.

Theoretical Reflection

Use of the two-domain mental health model orientation was important for tracking dimensions of both mental ill-health as well as well-being in the study population. This orientation allowed for a more complex and multi-dimensional understanding of resilience to be explored, as well as gender differences in exploring different social determinants of health and mental health. Mental ill-health concerns and well-being resources often co-exist and can dynamically influence each other (Kirmayer et al., 2011; Kalra et al., 2012; DeMarinis, 2014; Forsman et al., 2015; DeMarinis and Boyd-MacMillan, 2019; Boyd-MacMillan and DeMarinis, 2020). Mapping both areas and their interaction is important for clinicians' diagnosing and treatment planning processes.

Methodological Reflections: Strengths and Limitations

For this study we were able to recruit a fairly large and diverse number of participants, despite initial difficulties in reaching out to refugees or newly arrived immigrants. Working through community networks or key-persons increased the level of trust, and facilitated the distribution of the survey. We found that trust usually could be established by respecting the participants' opinions, maintaining a neutral political and religious position, and demonstrating knowledge and competence in the participants' culture. We were also able to reach non-Muslim minority groups from Iraq as well as women and younger age groups, groups that are sometimes underrepresented in research. Collaborating with an Arabic-speaking research assistant with cultural knowledge of the field facilitated recruitment—notwithstanding the suspiciousness and lack of trust that sometimes came with the current political, social, and sectarian conflicts and fault lines of the Arabic-speaking region (the Middle East and North Africa).

There are some limitations to our study. The use of convenience sampling limits the representativity of our sample and the generalizability of our results: the observed high rates of self-perceived health, the low levels of PTSD as well as of aspects of resilience, compared to what was reported in studies of other refugee samples, may reflect a selection bias. But there are also arguments in favor of convenience sampling as appropriate for exploratory research in which new theoretical ideas and hypotheses may be generated (Bryman, 2015). Our aim has not been to present the mental health of Iraqi refugees at large, but to give a rich description of a time-specific period in Sweden and a not so small, diverse population of Iraqi refugees (N = 410) from a wide range of aspects. We did not aspire to cover the larger population of Iraqi refugees, who migrated at different time periods during the late 20th and early 21st centuries, but focused on a delimited population of Iraqis, who arrived soon after the year 2000. We hope the results might be useful in other contexts, as new refugee populations from other conflicted regions continue to face similar issues.

Another limitation was technical. The survey involved many questions and some complicated instruments, which may have resulted in lower reliability. An example of a disruptive constellation of questions was when we asked the respondents to select only one alternative response to one type of question and this was followed by questions with several response alternatives. There were indications in the material that this approach led to misunderstandings.

Conclusions

The group of Iraqi individuals in this study, who had lived longer in their new country than subjects of comparable studies, showed relatively low levels of general mental health problems, including PTSD. Nevertheless, they remained vulnerable in some respects, notably with regard to individual and long-term psychological resilience.

Unemployment was high among the participants, even after a long period of living in Sweden. Social networks outside the family were weak, and authorities were not perceived as supportive. Authorities therefore need to address the challenge of answering the unmet needs of informational and concrete support.

Women evinced poor mental health in spite of signs of strong adaptation in other respects. Clinicians need to be aware of the risks and variations of psychosocial maladaptation and ill-health in refugees in general and women in particular.

The post-migration situation and the refugee's ways of managing need to be better understood in order to avoid too schematic views of the acculturation process. Variations in illness perception point to the importance for clinicians to avoid stereotyping in the encounter with refugee patients. The exploration of the individual's social world and subjective perceptions is crucial. The cultural formulation interview in the DSM-5 is a supportive tool in that exploration (Lewis-Fernández et al., 2014).

The gender differences found in our study should be viewed within a context of acculturation, where several determining single factors and patterns of interacting social and individual strengths and vulnerabilities play a central role. In a highly secularized society such as that in Sweden, with a strong individual goal-orientation and focus on self-reliance and gender equality, Iraqi women's comparatively strong ability to adapt to new situations and to evaluate themselves as hard-working members of Swedish society, may reflect—or have provided a basis for—a positive acculturation process. The same societal context may have been a greater challenge for the men. This difference may impact family acculturation processes in subsequent generations too.

Key Policy Messages

-It is important to provide women and men with practical resources and frameworks for self-fulfillment in education and work, at the same time as they are supported in using cultural coping mechanisms, such as religion and nature.

-In the framework of social integration in work and education, caregivers need to be aware of the high prevalence of negative psychosocial and mental ill-health among women and of the differing needs for support in women and men.

-Culturally and locally adapted social information and support by authorities, together with support to maintain links with and to form new social networks is important for integration of newcomers in society.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because by the time of the data collection, participants were not informed about the possibility of making data available to outside researchers. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Önver Cetrez, cetrez@teol.uu.se.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Swedish Ethical Review Authority. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

ÖÇ, VD, MS, and MG contributed conception and design of the study. ÖÇ organized the database and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. LB performed the statistical analysis. VD, MS, DT, and LB wrote sections of the manuscript. ÖÇ, VD, MS, DT, and LB contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We want to direct our gratitude to all the Iraqi participants, key persons from the different associations, and stakeholders in different municipalities, as well as Shakra et al. (2018), research assistant, for his valuable cultural knowledge and linguistic competency. For three of the researchers this work was supported by The Swedish Research Council under Grant 2009-2179.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsoc.2021.551105/full#supplementary-material

References

- Balboni T., Vanderwerker L. C., Block S. D., Paulk M. E., Lathan C. S., Peteer J. R., et al. (2007). Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life-treatment preferences and quality of life. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 555–560. 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry J. W. (2006). Stress perspectives on acculturation, in The Cambridge Handbook of Acculturation Psychology, eds Sam D. L., Berry J. W. (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; ), 43–57. 10.1017/CBO9780511489891.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt T. S., Khan K. T. (2008). The mental health of children affected by armed conflict: protective processes and pathways to resilience. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 20, 317–328. 10.1080/09540260802090363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogic M., Njoku A., Priebe S. (2015). Long-term mental health of war-refugees: a systematic literature review. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights. 15:29. 10.1186/s12914-015-0064-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-MacMillan E., DeMarinis V. (2020). Learning Passport: Curriculum Framework (IC-ADAPT SEL High Level Programme Design). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press & Cambridge Assessment. Available online at: https://www.cambridge.org/files/6615/8465/3401/The_IC-ADAPT_for_SEL_Programme_Design.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bryman A. (2015). Social Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cetrez ö. (2005). Meaning-making variations in acculturation and ritualization: a multi-generational study of Suroyo migrants in Sweden (Ph.D. diss). Uppsala University, Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, Psychologia et Sociologia Religionum 17, Uppsala. [Google Scholar]

- Cetrez Ö. (2011). The Next Generation Assyrians in Sweden: Religiosity as a functioning system of meaning within the process of acculturation. Mental Health Relig. Cult. 14, 473–487. 10.1080/13674676.2010.484061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cetrez Ö. (2015). ‘I feel Swedish, but my parents are from there …’: Crossing of identity borders among Assyrian youth in a multicultural context. Transactions 22, 161–174. [Google Scholar]

- Cetrez Ö., Ahmadi F., Erbil P. A. (2020a). Comparative survey study on meaning-making coping among cancer patients in Turkey. Religions 11:284. 10.3390/rel11060284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetrez Ö., DeMarinis V., Pettersson J., Shakra M. (2020b). Integration: Policies, Practices, and Experiences, Sweden Country Report. Working papers Global Migration: Consequences and Responses. Uppsala: Uppsala University. 10.5281/zenodo.3951714 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collie P., Kindon S., Liu J., Podsiadlowski A. (2010). Mindful identity negotiations: the acculturation of young Assyrian women in New Zealand. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 34, 208–220. 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.08.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connor K. M., Davidson J. R. T. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 18, 76–82. 10.1002/da.10113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor K. M., Sutherland S. M., Tupler L. A., Malik M. L., Davidson J. R. T. (1999). Fluoxetine in post-traumatic stress disorder: randomised, double-blind study. Br. J. Psychiatry. 175, 17–22. 10.1192/bjp.175.1.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig T. K. J., Jajua P., Warfa N. (2006). Mental health care needs of refugees. Psychiatry 5, 405–408. 10.1053/j.mppsy.2006.08.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daud A., af Klinteberg B., Rydelius P-A. (2008). Trauma, PTSD and personality: the relationship between prolonged traumatization and personality impairments. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 22, 331–340. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00532.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson J. R. T. (2018). CD-RISC. (2018). Manual. www.cd-risc.com (accessed July 10, 2019).

- DeMarinis V. (2014). Public mental health promotion, meaning-making and existential meaning: Challenges for person-centered care of refugees in a secular, pluralistic context, in Nordic Work with Traumatised Refugees: Do We Really Care, Eds G. Overland, eds Guribye E., Lie B. (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars; ), 316–324. [Google Scholar]

- DeMarinis V., Boyd-MacMillan E. (2019). A Mental Health Approach to Understanding Violent Extremism [EU Radical Awareness Network (RAN) Policy & Practice Report]. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/networks/radicalisation_awareness_network/about-ran/ran-h-and-sc/docs/ran_hsc_prac_mental_health_03062019_en.pdf (accessed January 21, 2021).

- Estroff S. E., Lachicotte S. W., Illingworth L. C., Johnston A. (1991). Everybody's got a little mental illness: accounts of illness and self among people with severe, persistent mental illnesses. Med. Anthropol. Q. 5, 331–369. 10.1525/maq.1991.5.4.02a00030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel M., Wheeler J., Danesh J. (2005). Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: a systematic review. Lancet. 365, 1309–1314. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61027-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finke R., Stark R. (1992). The Churching of America, 1776-1990. Winners and Losers in Our Religious Economy. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Forsman A. K., Wahlbeck K., Aarø L. E., Alonso J., Barry M. M., Brunn M., et al. (2015). Research priorities for public mental health in Europe: recommendations of the ROAMER project. Eur. J. Public Health. 25, 249–254. 10.1093/eurpub/cku232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganzevoort R. R. (1998). Religious coping reconsidered (part two): A narrative reformulation. J. Psychol. Theol. 26, 276–286. 10.1177/009164719802600305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen A. A., Bramsen I., Devillé W., van Willigen L. H., Hovens J. E., van der Ploeg H. M. (2006). Physical and mental health of Afghan, Iranian and Somali asylum seekers and refugees living in the Netherlands. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiol. 41, 18–26. 10.1007/s00127-005-0003-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorst-Unsworth C., Goldenberg E. (1998). Psychological sequelae of torture and organised violence suffered by refugees from Iraq: trauma-related factors compared with social factors in exile. Br. J. Psychiatry 172, 90–94. 10.1192/bjp.172.1.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn R. A., Truman B. I. (2015). Education improves public health and promotes health equity. Int. J. Health Serv. 45, 657–678. 10.1177/0020731415585986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynie M. (2018). The social determinants of refugee mental health in the post-migration context: a critical review. Can. J. Psychiatry 63, 297–303. 10.1177/0706743717746666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamil H., Hakim-Larson J., Farrag M., Kafaji T., Jamil L. H., Hammad A. (2005). Medical complaints among iraqi american refugees with mental disorders. J. Immigr. Health. 7:3. 10.1007/s10903-005-3671-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamil H., Nassar-McMillan S., Lambert R., Wang Y., Ager J., Arnetz B. (2010). Pre- and post-displacement stressors and time of migration as related to self-rated health among Iraqi immigrants and refugees in Southeast Michigan. Med. Confl. Surv. 26, 207–222. 10.1080/13623699.2010.513655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra G., Christodoulou G., Jenkins R., Tsipas V., Christodoulou N., Lecic-Tosevski D., et al. (2012). European psychiatry association. mental health promotion: guidance and strategies. Eur. Psychiatry. 27, 81–86. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kira I. A., Lewandowski L. A., Templin T. N., Ramaswamy V., Ozkan B., Mohanesh J. (2009). The effects of post-retribution inter-group forgiveness: the case of Iraqi refugees. Peace Conflict J. Peace Psychol. 15, 385–413. 10.1080/10781910903158669 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer L. J., Dandeneau S., Marshall E., Phillips M. K., Williamson K. J. (2011). Rethinking resilience from indigenous perspectives. Canad. J. Psychiatry 56, 84–91. 10.1177/070674371105600203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laban C. J., Gernaat H., Komproe I. H., van der Tweel I., De Jong J. T. V. (2005). Postmigration living problems and common psychiatric disorders in Iraqi asylum seekers in the Netherlands. J. Nerv. Mental Dis. 193, 825–832. 10.1097/01.nmd.0000188977.44657.1d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laban C. J., Gernaat H. B., Komproe I. H., Schreuders B. A., De Jong J. T. (2004). Impact of a long asylum procedure on the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Iraqi asylum seekers in The Netherlands. J. Nervou. Mental Dis. 192, 843–851. 10.1097/01.nmd.0000146739.26187.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Fernández R., Aggarwal N. K., Bäärnhielm S., Rohlof H., Kirmayer L. J., Weiss M. G., et al. (2014). Culture and psychiatric evaluation: operationalizing cultural formulation for DSM-5. Psychiatry 77, 130–154. 10.1521/psyc.2014.77.2.130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. (2007). Achieving health equity: from root causes to fair outcomes. Lancet 370, 1153–1163. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61385-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawani F. N. (2014). Social determinants of refugee mental health. in Refuge and Resilience: Promoting Resilience and Mental Health among Resettled Refugees and Forced Migrants, eds Simich L., Andermann L. (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; ), 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie K. J., Tuck A., Agic B. (2014). Mental Healthcare Policy for Refugees in Canada, in Refuge and Resilience: Promoting Resilience and Mental Health among Resettled Refugees and Forced Migrants, eds Simich L., Andermann L. (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; ), 181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Migration Agency [Migrationsverket]. (2017). Asylsökande Till Sverige 2000–2016. [Asylum Seekers in Sweden 2000–2016]. Available online at: https://www.migrationsverket.se/Om-Migrationsverket/Statistik.html (accessed April 22, 2017).

- Miller A. S., Hoffmann J. P. (1995). Risk and religion: an explanation of gender differences in religiosity. J. Sci. Study Rel. 34, 63–75. 10.2307/1386523 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson M., Meredith Hess J., Isakson B., Goodkind J. (2016). ‘Seeing the life’: redefining self-worth and family roles among Iraqi refugee families resettled in the United States. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 17, 707–722. 10.1007/s12134-015-0441-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson A., Bryant R. A., Brooks B., Steel Z., Silove D. (2009). Fear of cultural extinction and psychopathology among mandaean refugees: an exploratory path analysis. CNS Neurosci. Therap. 15, 227–236. 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2009.00094.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padela A. I., Heisler M. (2010). The association of perceived abuse and discrimination after september 11, 2001, with psychological distress, level of happiness, and health status among Arab Americans. Am. J. Public Health 100, 284–291. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.164954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panter-Brick C., Eggerman M. (2012). Understanding culture, resilience, and mental health: the production of hope, in The Social Ecology of Resilience. A Handbook of Theory and Practice, ed Ungar M. (London: Springer; ), 369–386. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament K. I. (1997). The Psychology of Religion and Coping: Theory, Research, Practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Patalay P., Fitzsimons E. (2016). Correlates of mental illness and wellbeing in children: are they the same? results from the UK millennium cohort study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 55, 771–783. 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins A., Ouimette P., Kimerling R., Cameron R. P., Hugelshofer D. S., Shaw-Hegwer J., et al. (2003). The Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychiatry 9, 9–14. 10.1185/135525703125002360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaniah N. V., Sharpe J. P., Byravan A. (1999). Hardiness and major personality factors. Psychol. Rep. 84, 497–500. 10.2466/pr0.1999.84.2.497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rian E., Hodge D. R. (2010). Developing cultural competency with Mandaean clients: synchronizing practice with the light world. Int. Soc. Work 53:542. 10.1177/0020872809360351 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rudmin F. (2009). Constructs, measurements, and models of acculturation and acculturative stress. Int. J. Int. Relations. 33, 106–123. 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2008.12.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaudt V. A., Bosson R., Williams M. T., German B., Hooper L. M., Frazier V., et al. (2020). Traumatic experiences and mental health risk for refugees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17:1943. 10.3390/ijerph17061943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakra M., Wirman J., Szalanska J., Cetrez Ö. (2018). Sweden—Country Report, Legal and Policy Framework of Migration Governance. Working Papers Global Migration, RESPOND, D1.2.

- Shannon P., O'Dougherty M., Mehta E. (2012). Refugees' perspectives on barriers to communication about trauma histories in primary care. Ment. Health Fam. Med. 9, 47–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirina S. R., Bikmenb N., Mira M., Finec M., Zaalc M., Katsiaficas D. (2008). Exploring dual identification among Muslim-American emerging adults: a mixed methods study. J. Adolesc. 31, 259–279. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söndergaard H. P., Hansson L. O., Theorell T. (2004). The inflammatory markers C-creative protein and serum amyloid A in refugees with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinica Chimica Acta. 342, 93–98. 10.1016/j.cccn.2003.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel Z., Silove D., Brooks R., Momartin S., Alzuhairi B., Susljik I. (2006). Impact of immigration detention and temporary protection on the mental health of refugees. Br. J. Psychiatry 188, 58–64. 10.1192/bjp.bp.104.007864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Orozco C. (2000). Identities under siege: immigration stress and social mirroring among the children of immigrants. in Cultures Under Siege: Social Violence and Trauma eds Robben A., Suraez-Orozco M. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ), 194–226. [Google Scholar]

- Sundell Lecerof S. (2010). Olika villkor - olika hälsa: Hälsan bland irakier i åtta av Sveriges län 2008. [Different Conditions - Different Health: Health Among Iraqi Immigrants in Eight Swedish Counties 2008] A Report by Malmö University, Malmö. Within the Research Project IMHAd (Impact of Multicultural Health Advisors).

- Sundvall M., Titelman D., DeMarinis V., Borisova L., Çetrez Ö. (2020). Safe but isolated—an interview study with Iraqi refugees in Sweden about social networks, social support, and mental health. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 10.1177/0020764020954257 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor E. M., Yanni E. A., Pezzi C., Guterbock M, Rothney E., Harton E., et al. (2014). Physical and mental health status of Iraqi refugees resettled in the United States. J. Immigrant. Minorirty Health 16, 1130–1137. 10.1007/s10903-013-9893-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinghög P., Arwidson C., Sigvardsdotter E., Malm A., Saboonchi F. (2016). Nyanlända och asylsökande i Sverige: En studie av psykisk ohälsa, trauma och levnadsvillkor. [Newly Arrived and Asylum Seekers in Sweden: A Study on Mental Ill-health, Trauma and Living Conditions.] Röda Korsets Högskolas rapportserie. Stockholm: Röda Korset. 2016:1. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy E. M., Whittaker J. K. (1990). The social network map: assessing social support in clinical practice. families in society: J. Contemp. Hum. Serv. 71, 461–470. 10.1177/104438949007100802 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar M. (2008). Resilience across cultures. Br. J. Soc. Work 38, 218–235. 10.1093/bjsw/bcl343 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vaishnavi S., Connor K., Davidson J. T. (2007). An abbreviated version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), the CD-RISC2: Psychometric properties and applications in psychopharmacological trials. Psychiatry Res. 152, 293–297. 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Tubergen F. (2006). Religious affiliation and attendance among immigrants in eight western countries: individual and contextual effects. J. Sci. Study Relig. 45, 1–22. 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2006.00002.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Tubergen F. (2010). Determinants of second language proficiency among refugees in The Netherlands. Soc. Forces. 89, 515–534. 10.1353/sof.2010.0092 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh F. (2006). Strengthening Family Resilience. New York, NY: Guildford. [Google Scholar]

- Warda W. K., al-Maffraji H. S. A., Youhanna T., Arif N., Samoeel A. C. (2018). Iraq-Country Report: Legal and Policy Framework of Migration Governance, in Working Papers Global Migration, RESPOND, D1.2. 10.5281/zenodo.1418575 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waysman M., Schwarzwald J., Solomon Z. (2001). Hardiness: an examination of its relationship with positive and negative long term changes following trauma. J. Trauma. Stress. 14, 531–548. 10.1023/A:1011112723704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss M. (1997). Explanatory Model Interview Catalogue (EMIC): framework for comparative study of illness. Transcult. Psychiatry 34, 235–263. 10.1177/136346159703400204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Welzel C. (2013). Freedom Rising: Human Empowerment and the Quest for Emancipation. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wrobel N. H., Farrag M. F., Hymes R. W. (2009). Acculturative stress and depression in an elderly arabic sample. J. Cross-Cultural Gerontol. 24, 273–290. 10.1007/s10823-009-9096-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because by the time of the data collection, participants were not informed about the possibility of making data available to outside researchers. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Önver Cetrez, cetrez@teol.uu.se.