Abstract

Background

Lung-MAP (S1400) is a completed Biomarker-Driven Master Protocol designed to address an unmet need for better therapies for squamous non-small cell lung cancer (sqNSCLC). Lung-MAP (S1400) was created to establish an infrastructure for biomarker-screening and rapid regulatory-intent evaluation of targeted therapies and was the first biomarker-driven master protocol initiated with the United States National Cancer Institute (NCI).

Methods

Lung-MAP (S1400) was conducted within the National Clinical Trials Network of the NCI using a public-private partnership. Eligible patients were aged 18 years or older, had stage IV or recurrent sqNSCLC previously-treated with platinum-based chemotherapy and Zubrod(ECOG) performance status 0 to 2. The study included a screening component using the FoundationOne® assay (Foundation Medicine, Inc; Cambridge USA) and a clinical trial component with biomarker-driven “sub-studies” (BMDS) and “non-match sub-studies” (NMS) for BMDS-ineligible patients. Patients were pre-screened and received their sub-study assignment upon progression or screened-at-progression and received their sub-study assignment upon completion of testing. Patients could enroll onto additional sub-studies after progression on a sub-study. The study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02154490, all research is completed.

Findings

From June 16, 2014 – January 28, 2019, 1864 patients enrolled, 1841 (99%) submitted tissue, 1674/1841 (91%) had biomarker results, and 1404/1864 (75%) received a sub-study assignment. Of assigned, 655 (47%) registered to a sub-study. The BDMS evaluated taselisib(PIK3CA), palbociclib (cell cycle gene alterations), AZD4547 (FGFR), rilotumumab/erlotinib (MET), talazoparib (homologous repair deficiency), and telisotuzumab vedotin (MET). The NMS evaluated durvalumab, and nivolumab/ ipilimumab for anti-PD-(L)1 naïve disease, and durvalumab/tremelimumab for anti-PD-(L)1 relapsed disease. Combing data from the sub-studies, the response rate was 7% for targeted therapy (10 responses in 143 patients), 17% for anti-PD-(L)1 therapy (53 of 315) for immune-therapy naive disease, and 5% for docetaxel (3 of 56) in 2nd line. Median OS was 5·9 months (95% CI: 4·8 – 7·8) for the targeted therapy arms, 7·7 months (95% CI: 6·7 – 9·2) for the docetaxel arms, and 10·8 months (95% CI: 9·4 – 12·3) for the anti-PD-(L)1-containing arms.

Interpretation

Lung-MAP (S1400) met its goal to quickly address biomarker-driven therapy questions in sqNSCLC. Early 2019, a new screening protocol was implemented expanding to all histologic types of NSCLC and to add focus on immunotherapy combinations for anti-PD-(L)1 therapy-relapsed disease. With these changes, Lung-MAP remains true to its goal to focus on unmet needs in the treatment of advanced lung cancers.

Background

The Lung Cancer Master Protocol (Lung-MAP), part of the precision medicine initiative of the United States National Cancer Institute (NCI), was created to facilitate the discovery of more effective therapies for previously-treated advanced squamous non-small cell lung cancer (sqNSCLC). To achieve this goal, Lung-MAP established an infrastructure for the conduct of biomarker-screening and rapid evaluation of molecularly-targeted therapies in biomarker-defined subgroups which could lead to regulatory approval.

The premise for Lung-MAP was that progress in sqNSCLC would follow successes in other subtypes of NSCLC by the identification effective molecularly-targeted therapies for oncogene drivers (e.g. EGFR and ALK).1 This rationale was supported by the recent identification of potentially actionable and/or “druggable” molecular alterations in sqNSCLC within sequencing efforts such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) combined with advances in clinically applicable next generation sequencing (NGS) technologies.1–6 Given the lack of progress for decades there was a compulsion to improve the efficiency of therapeutic drug evaluation in sqNSCLC.

Evaluation of molecularly targeted therapies in populations with rare mutations using conventional stand-alone clinical trial designs had proven to be challenging logistically or infeasible. Stand-alone trials in rare populations require screening of large numbers of patients to enroll a small number of patients; thus, requiring multi-center accrual. Single institutions may only enroll at most 1 or 2 patients despite screening many patients, making participation infeasible due to cost or logistical constraints. Additionally, patients may find waiting multiple weeks with a small chance of study participation unacceptable. The overall impact can be that studies in rare populations may either be infeasible or take a long time to completion.

Thus, the concept of Biomarker-driven Master Protocols, in which multiple investigational therapies matched to biomarkers are tested within a single clinical trial infrastructure, emerged as an approach to accelerate drug testing and approval in biomarker-defined subgroups.7–10 Biomarker-driven Master Protocols received immediate and enthusiastic support by the NCI, Food and Drug Administration (FDA), industry, patient advocacy groups, and academic researchers.11 Moreover, a natural efficiency strategy was to use the established infrastructure of the NCI’s National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN) to conduct Biomarker-Driven Master Protocols. Implemented in June 2014, Lung-MAP was the first master protocol for precision medicine launched within the NCTN, as well as the only one to integrate the potential for regulatory approval of new drug candidates.12–20

This paper describes the Lung-MAP (S1400) protocol, including protocol design, patient eligibility, patients screened, results of study conduct, and some of the lessons learned from the conduct of this innovative trial.

Methods

Protocol Design

Lung-MAP (S1400) consisted of a screening component and an investigational study component. The screening component established common eligibility criteria for every sub-study and procedures for specimen submission and analysis. The investigational study component consisted of multiple independently conducted and analyzed sub-studies of two categories: “biomarker-driven” for patients eligible based on detection of a biomarker or a set of biomarkers and “non-match” sub-studies for otherwise eligible patients not meeting the criteria to enroll in a biomarker-driven sub-study. New sub-studies were independently added as new ideas were developed and closed to accrual as they met the criteria for closure. Lung-MAP (S1400) had a single Investigational New Drug application (IND) covering the overarching screening study and individual therapeutic sub-studies.

Partnership Structure, Study Conduct and Accruing Sites

Lung-MAP (S1400) was conducted through a public-private partnership including the Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (CTEP) at the NCI, the adult NCTN Groups (Alliance, ECOG-ACRIN, NRG, and SWOG), the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health, and Friends of Cancer Research. The Lung-MAP (S1400) was reviewed by CTEP and was approved by the institutional review board at each participating site. Sites were responsible for obtaining written informed consent. Trial governance was comprised of representatives from the partners. A Drug Selection Committee evaluated candidate drugs and biomarkers using pre-specified criteria based on scientific and practical considerations (Appendix page [pg.] 5–6). A Trial Oversight Committee provided guidance on study design and conduct. The SWOG Data Safety and Monitoring Committee was responsible for oversight of all sub-studies.

Lung-MAP (S1400) was scientifically and operationally led by SWOG with clinical and translational leadership representation from all NCTN Groups. The Canadian Cancer Trials Group participated between December 18, 2015 and July 12, 2018, closing the study due to challenges with drug distribution across the US-Canadian border. Since inception, the FDA was an active collaborator. Participation in the trial was available across all NCTN sites, including those in the NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP).

Eligibility

Eligibility criteria at inception specified that patients were ≥18 years of age, had pathologically proven Stage IV or recurrent sqNSCLC confirmed by tumor biopsy and/or fine-needle aspiration without mixed histologies, no other prior untreated malignancies, progressive disease in the opinion of the treating physician following one prior treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy, no EGFR mutation or ALK fusion, and sufficient tumor tissue for biomarker analysis. Eleven months after activation eligibility was modified to allow all previously-treated stage IV or recurrent disease (second and greater lines) with at least one line including platinum-based chemotherapy. Also, at this time, the option to be pre-screened during previous treatment for stage IV or recurrent disease was added. Patients with prior systemic therapy for earlier stage (I–III) lung cancer were eligible if progression on platinum-based chemotherapy occurred within one year from the last date that the patient received that therapy. Initially allowing Zubrod (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 0 – 2, 18 months after activation PS 2 was disallowed due to the addition of pre-screening and concerns with toxicities of immune-checkpoint inhibitors (See Figure 1 and Table 2 for additional detail).

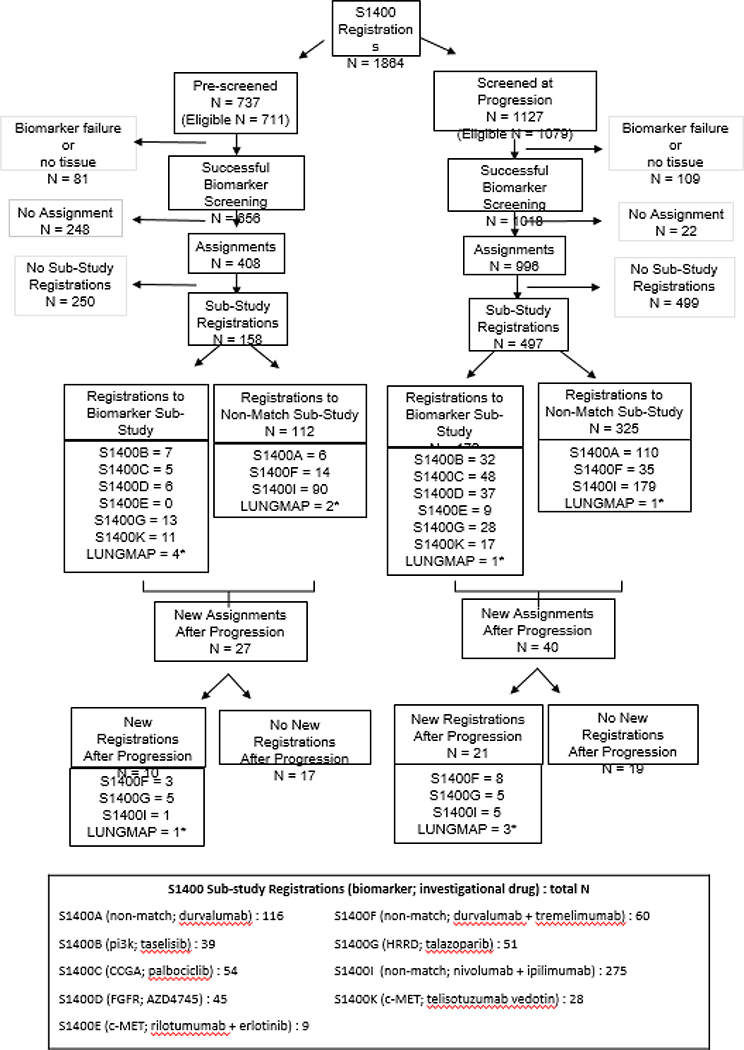

Figure 1. Lung-MAP (S1400) Screening Registrations, Assignments, and Sub-study Registrations Summary.

Footnotes:

# The sub-study assignment process differed for pre-screened patients and screened at progression patients. Only patients who had successful biomarker screening were assigned to sub-studies. Pre-screened patients were assigned to a sub-study upon notification by the site that the patient had progressed on their prior therapy. If the notice was never submitted, the patient would not have received a sub-study assignment. Patients screened at progression received their sub-study assignment as soon as the biomarker results were available.

*See Tables 2 and S7 for sub-study descriptions. S1400A evaluated durvalumab in anti-PD-(L)1-naïve squamous cell carcinoma (SCCA); S1400B evaluated taselisib for PI3KCA-positive SCCA; S1400C evaluated palbociclib in SCCA with cell cycle gene alterations; S1400E evaluated rilotumumab + erlotinib in c-MET positive SCCA; S1400F evaluated durvalumab + tremelimumab in ICI-relapsed/refractory SCCA; S1400G evaluated talazoparib in homologous recombinant repair deficiency positive SCCA; S1400I evaluated nivolumab + ipilimumab versus nivolumab in ICI-naïve SCCA; S1400K evaluated ABBV-399 in c-MET positive SCCA. The S1400 protocol was active between June 16, 2014 and January 28, 2019. Simultaneous with the closure of S1400, a new screening protocol called LUNGMAP was opened. Accrual to sub-studies activated under LUNGMAP as listed under that name.

1a-3b: See Appendix page 1 for reasons.

Table 2.

S1400 Sub-study Design and Implementation Details

| Sub-study ID | Biomarker/Population1 | Therapies | Design | Sample Size Goal (# eligible) | Primary Endpoint | Study Outcome | Dates of activity (open – close), Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1400A | Non-match, anti-PD-(L)1 naïve | Investigational:

Durvalumab SoC: Docatexel |

Original: Phase

II/III Modified: Single arm phase II |

Original: 400 Modified: 100 total, 30 PD-L1 high |

Original: PFS and OS Modified: Response3 |

Administratively closed prior to completion of accrual | 6/16/14–12/18/15 18

months SoC arm closed 5/26/15 |

| S1400B | PI3KCA alteration by FMI | Investigational: Taselisib SoC: Docetaxel |

Original: Phase

II/III Modified: Single arm phase II |

Original: 400 Modified: 59 total 40 in PAP |

Original: PFS and OS Modified: Response3 |

Closed at Interim analysis for futility | 6/16/14–12/12/16, 30

months SoC arm closed 12/18/15 |

| S1400C | Cell Cycle Gene Alterations by FMI | Investigational:

Palbociclib SoC: Docetaxel |

Original: Phase

II/III Modified: Single arm phase II |

Original: 312 Modified: 40 |

Original: PFS and OS Modified: Response3 |

Closed at Interim analysis for futility | 6/16/14–09/01/16, 27

months SoC arm closed 12/18/15 |

| S1400D | FGFR Alteration by FMI | Investigational: AZD4547 SoC: Docetaxel |

Original: Phase

II/III Modified: Single arm Phase II |

Original: 302 Modified: 40 |

Original: PFS and OS Modified: Response2 |

Closed at Interim analysis for futility | 6/16/14–10/31/16, 29

months SoC arm closed 12/18/15 |

| S1400E | c-MET by IHC (Dako MET IHC PharmDx™ Kit) | Investigational: Rilotumumab +

Erlotinib SoC: Erlotinib |

Phase II/III | 326 | PFS and OS | Closed due to discontinuation of development of rilotumumab | 6/16/14–11/25/14 |

| S1400F | Non-match, anti-PD-(L)1 relapsed/refractory | Investigational: Durvalumab +

Tremelimumab SoC: N/A |

Single arm Phase II | 60 per cohort | Response2 | AR: closed at interim analysis for

futility PR: Passed first interim analysis, closed due to changes in SoC treatment and feasibility |

AR: 10/02/17–11/6/19, 25

months PR: 10/02/17– 3/24/20, 30 months |

| S1400G | Homologous recombinant repair deficiency (HRRD) genes by FMI | Investigational:

Talazoparib SoC: N/A |

Single arm Phase II | 60 Total 40 in the PAP | Response2 | Closed at interim analysis for futility2 | 2/7/17–7/23/18, 17 months |

| S1400I | Non-match, anti-PD-(L)1 naïve | Investigational: Nivolumab +

Ipilimumab SoC: Nivolumab |

Phase III | 332 | OS | Closed at interim analysis for futility | 12/18/15–04/23/18, 28 months |

| S1400K | c-MET by IHC (Ventana Rabbit SP44 Antibody c-MET Assay) | Investigational: ABBV-399 SoC: N/A |

Single arm Phase II | 40 | Response2 | Closed at interim analysis for futility. | 2/5/18–12/21/18, 11 months |

Common eligibility criteria for registration to sub-study: measurable disease, no prior systemic therapy within 21 days prior to sub-study registration, and recovery (≤ grade 1) from any side effects of prior therapy. Localized palliative radiation was allowed if completed ≥14 days prior to sub-study registration, all other radiation treatment must have been completed ≥28 days prior to sub-study registration. A baseline diagnostic scan (CT or MRI) was required within 28 days of sub-study registration; and a brain scan (CT or MRI) for evaluation of CNS disease was required within 42 days prior to sub-study registration (no leptomeningeal disease, spinal cord compression, or untreated or uncontrolled brain metastases allowed unless asymptomatic for at least 14 days following treatment, and patient was off corticosteroids for at least 1 day prior to sub-study registration.)

Response: confirmed or unconfirmed, complete or partial response by version RECIST 1.1.

Biomarker Platform and Screening Requirements

On-study NGS screening was required and performed by Foundation Medicine, Inc. (FMI) using Foundation One®6,21, which was the selected platform based on a Request for Proposal process. Mutational analysis was performed on archival formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor specimens in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified and College of American Pathologists (CAP)-accredited laboratory (FMI, Cambridge, MA). Genomic DNA (≥50 ng) was extracted from FFPE specimens and sonicated to ~200bp fragments. Material underwent whole-genome shotgun library construction and hybridization-capture of at least 236 genes and selected introns of 19 genes involved in rearrangements. Using the Illumina® HiSeq 2000, 2500, and 4000 platforms, hybrid-capture-selected libraries were sequenced using 49 × 49bp paired-end reads to high uniform depth. Sequence data were processed using a customized analysis pipeline designed to accurately detect base substitutions, small insertions and deletions, focal copy number amplifications, homozygous gene deletions, and genomic rearrangements. Additionally, screening for c-MET expression by immunohistochemistry was intermittently performed (Table 2). A tumor block or a minimum of 12 unstained slides were required, although up to 20 slides were requested. The treating institution’s local pathologist was required to confirm adequate tissue was available before tissue submission. Adequate tissue was defined as ≥ 20% tumor cells and ≥ 0.2 mm3 tumor volume. If the initial submission was inadequate or failed testing, sites could submit additional tissue for screening. Patients for whom biomarker testing failed were not eligible to register to any of the sub-studies.

Sub-study Assignment Procedures

Sub-study assignments were to be reported within 16 days from tissue submission for patients screened-at-progression and within one day of notification of progression for pre-screened patients. Subsequently, detection of exactly one eligibility biomarker resulted in assignment to the associated biomarker-driven sub-study. Detection of more than one eligibility biomarker resulted in randomized sub-study assignment using a weighted randomization procedure that favored sub-studies with lower prevalence biomarkers. Finally, patients with successful biomarker analysis and not eligible for any of the biomarker-driven sub-studies were assigned to a non-match sub-study. All patients who did not register to a sub-study were followed for survival.

Sub-study Designs

Utilizing a modular design for the initiation, conduct, database build, and completion of sub-studies, each sub-study was independently conducted and analyzed. The statistical designs were selected from a limited set of design templates. The use of design templates allowed for consistency, efficient development, and streamlined the approvals process both at the NCI and FDA. However, using the template design as a guide, provided the flexibility tailor designs to the specific goals of individual drug/biomarker combination.

Initially the sub-studies were designed as randomized phase II/III studies, such that, if successful they could result in regulatory approval of the biomarker/targeted therapy pairs and this design was reviewed and approved of by the FDA. When nivolumab received regulatory approval for the treatment of previously-treated sqNSCLC, replacing docetaxel as the standard of care, the initial sub-studies were modified to be single arm, signal-seeking trials. As Lung-MAP is set up to provide regulatory level data, the new pathway for these sub-studies would be to either pursue regulatory approval based on single arm data, if the response rates were sufficiently high and durable or to initiate a randomized phase III against the current standard of care. As each new sub-study is being developed, the new sub-study protocol is submitted to the FDA as an update to the overarching IND for Lung-MAP. The specific pathway for registration for each sub-study is discussed with the FDA and review meetings are solicited if sub-study is intended to be submitted to the agency.

Sub-studies and Evaluated Investigational Therapies

The following biomarker-driven therapies were evaluated: taselisib, a Pi3-kinase inhibitor in PIK3CA positive disease; palbociclib, a CDK4/6 inhibitor in cell cycle gene alteration positive disease; rilotumumab and erlotinib, a monoclonal antibody directed against MET and erlotinib an EGFR inhibitor in c-MET positive disease; AZD4547, an FGFR inhibitor in FGFR positive disease, talazoparib, a PARP inhibitor for homologous recombinant deficiency positive disease; and ABBV-399, an antibody conjugate against MET, in c-MET positive disease. Non-match sub-studies evaluated durvalumab and nivolumab and ipilimumab randomized against nivolumab for anti-PD-(L)1-naïve disease; and durvalumab and tremelimumab for anti-PD-(L)1-relapsed/refractory disease (see Table 2 and xx). From June 16, 2014 to December 18, 2015 evaluation of taselisib, pablociclib, AZD4547 included randomization against docetaxel. From June 16, 2014 to May 26, 2015 evaluation of durvalumab included randomization against docetaxel.

Each sub-study is published independently, and the sub-study manuscripts include detail on the statistical designs implemented for that specific sub-study. The studies for taselisib, palbociclib, and AZD4547 are published.22–27 The remaining sub-studies will be published soon. Additionally, the study team is planning a separate manuscript that describes the statistical underpinnings of the Lung-MAP studies. This report describes the conduct of the master protocol.

Metrics for the Master Protocol Infrastructure

To evaluate the primary objective of the study which was to establish an infrastructure and efficiently evaluate targeted therapies in biomarker subgroups a series of analyses were performed, most of which are descriptive. The infrastructure was evaluated by the number of patients who successfully proceeded through the steps of Lung-MAP (S1400). Screening types were evaluated by comparing survival between the two types, and overall outcomes of the study evaluated by pooling data from treatment types.

To evaluate if there was a survival difference by screening type, the method of Kaplan-Meier was used to estimate the survival distribution for assigned patients alive at least two weeks after sub-study assignment. The analyses included the subset alive at least two weeks from assignment given that this is the typical window needed to work up a patient for eligibility. Overall survival (OS), defined as the duration from 2 weeks after assignment to death due to any cause or censored at the date of last contact, was compared using a log-rank test and summarized with a hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval using a Cox model. A significance level of 5% was used.

To summarize clinical outcomes, the response rate (complete, partial, confirmed or unconfirmed by RECIST 1.1), progression-free survival (PFS) and OS distributions were evaluated in an exploratory analysis for the targeted therapies, docetaxel, and anti-PD-(L)1 therapies (durvalumab, nivolumab+ipilimumab or nivolumab) for anti-PD-(L)1-naïve disease. For these analyses, PFS was defined as the duration from sub-study registration to progression per RECIST 1.1 or death due to any cause (which ever came first) and OS followed the definition above measured from sub-study registration. This analysis includes the 143 patients meeting the eligibility criteria (see sub-study publications for eligibility information) who received targeted therapy as their first line of therapy within Lung-MAP, 56 eligible patients who received docetaxel within Lung-MAP, and 315 eligible patients who received anti-PD-(L)1 therapy for naïve disease as their first line of therapy within Lung-MAP. Treatments were not statistically compared as these combine data across sub-studies. Statistical analyses were performed with R Studio Version 1.2.5033. The study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02154490.

Role of the Funding Source

The study was funded by the NCI and the Pharmaceutical Collaborators (PCs) for the sub-studies through the Public-Private Partnership. The NCI participated in the study design, data interpretation, and writing of the report. The PCs participated in the sub-study designs and review of the report. The sponsor, SWOG was responsible for study design, data collection, analysis, and writing of the report. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and the corresponding author had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. MWR, KM, JM, JM, and MLL had access to the raw data.

Results

Lung-MAP (S1400) was open to enrollment between June 15, 2014 and January 28, 2019 at over 750 sites across the NCTN; 436 sites enrolled at least one patient. The median number (interquartile range [IQR]) of patients accrued at a site was two (one-six) with a maximum of 45 patients accrued at a site.

As described in Figure 1, 1864 patients with stage IV or recurrent sqNSCLC were enrolled to the screening component. After pre-screening was added, 46% (737/1585) were pre-screening registrations. Of the 1864 registrations, 1841 (99%) had tissue submitted and NGS testing was successful for 1592/1841 (86%) of the initial submissions. Of the 249 specimens which failed initial testing, 98 patients had tissue resubmitted (one or more times) for biomarker profiling and of them, repeated biomarker testing was successful for 82 (84%), for an overall patient level success rate of 1674/1841 (91%). The reasons for failure are detailed in the Supplementary Materials (Appendix pg. 7). Of 81 pre-screened and 109 screened-at-progression patients without biomarker results, 12 (15%) pre-screened and 11 (10%) screened-at-progression did not have tissue submitted and 69 (85%) pre-screened and 98 (90%) had tissue that was either insufficient for biomarker profiling or failed testing. Of the 1941 total tissue submissions (among 1841 patients with tissue), 527 (27%) were fresh tissue biopsy specimens. Biomarker results were reported within 16 days from tissue submission for 1462/1841 (79%) and the median time (IQR) was 14 days (11–16 days).

Of the patients with biomarker results, 1404/1674 (75%) were assigned to a sub-study. For assigned patients, the median (IQR) time from screening registration to sub-study assignment was 0·5 months (0·4 – 0·5 months) for screened-at-progression and 3·3 months (1·4 – 6·7 months) for pre-screened patients. The reasons pre-screened patients lacked a sub-study assignment (N=248) were: death prior to report of progression (N = 162, 65%), progressive disease not reported on current line of treatment (N = 65, 26%), and the patient was not eligible for any actively accruing sub-studies (N = 21, 8%). The reasons screened-at-progression patients lacked a sub-study assignment (N=22) were: the patient was not eligible for any actively accruing sub-studies (N = 15, 68%) and ALK fusions or EGFR mutations were detected on FMI screening (N = 7, 32%) [see Appendix pg 1].

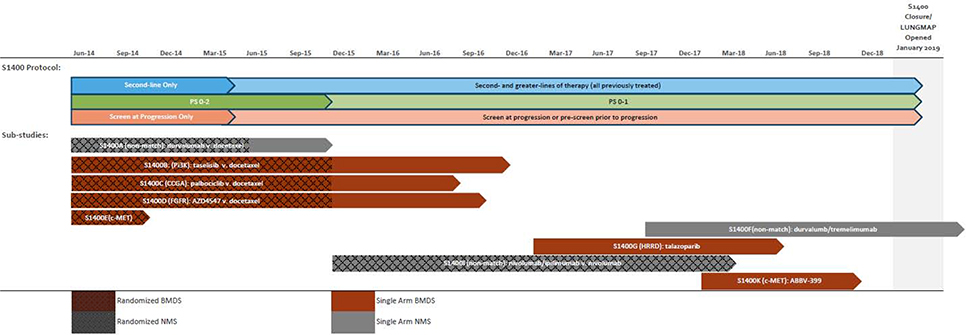

Of the patients assigned to a sub-study, 655/1404 (47%) registered to a sub-study (158/408 (39%) pre-screened and 497/996 (50%) screened-at-progression). For patients registered to a sub-study, the median (IQR) time from screening to sub-study registration was 0·9 months (0·7 – 1·1 months) for screened-at-progression and 3·5 months (2·0 – 6·0 months) for pre-screened patients. Reasons for non-registrations are summarized in the Supplementary Materials (Appendix pg. 1 ). The major reason for lack of participation in a sub-study was a period when there were limited biomarker-driven sub-studies and no non-match sub-studies available for patients previously-treated with an anti-PD-(L)1 therapy (see Figure 2). Forty-two percent of pre-screened (N = 104 of 250) and 47% of screened-at-progression (N=234 of 499) patients did not register to a sub-study because there were no available sub-studies. Less frequent reasons included rapidly progressing disease (symptomatic deterioration or death prior to registration, pre-screened: N (%) = 55 (22%) of 104, screened-at-progression =116 (23%) of 499) and patient refusal or investigator decision (pre-screened: N (%) = 51 (20%) of 104, screened-at-progression =93 (19%) of 499).

Figure 2. Timelines for Sub-studies, Activation, Design and Eligibility Changes for S1400.

Footnotes: v. = versus. CCGA = cell cycle gene alterations; HRRD = homologous recombinant repair deficiency. S1400E therapies were: rilotumumab + erlotinib v. erlotinib. See Tables 2 and S7 for full sub-study descriptions.

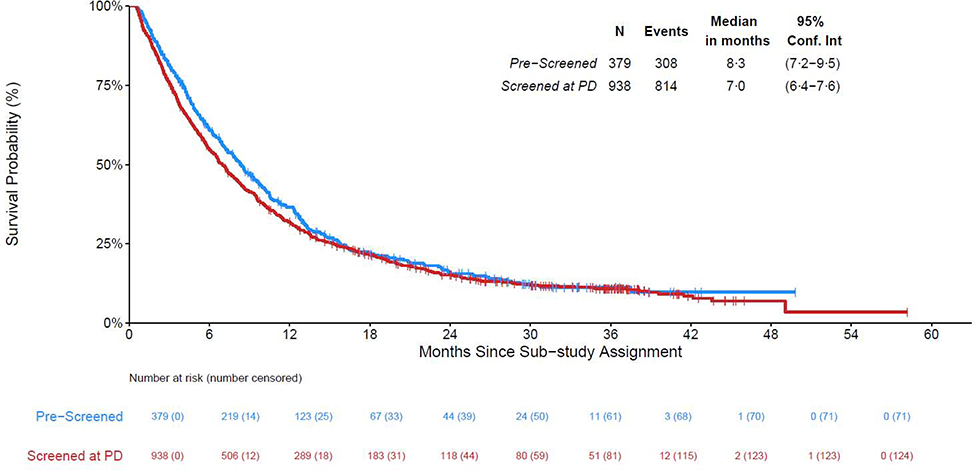

The characteristics of eligible patients enrolled in the screening component are described in Table 1. Of the 1404 patients with sub-study assignments, 1317 were alive at least two weeks from assignment (379 pre-screened, 938 screened at progression); median (IQR) follow-up among the subset alive at last contact (N= 194) is 27 (14–36) months and Figure 3 displays the survival curves by screening type. Of the 379 pre-screened patients, 308 deaths have been reported and median survival was 8·3 months (95% CI: 7·2 –9·5). Of the 938 screened-at-progression patients, 814 deaths have been reported and median survival was 7·0 months (95% CI: 6.4 – 7.6). Screened-at-progression patients did not have statistically shorter survival than pre-screened patients (HR [95% CI]: 1·10 [0·97 – 1·26], p = 0·15).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Eligible Patients Enrolled to be Screened on Lung-MAP (S1400)

| Pre-Screened prior to Progression1 (n=711) | Screened at Progression (n=1079) | Total (n=1790) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age median | 67 | 67 | 67 | |||

| IQR | 61–73 | 60–73 | 61–73 | |||

| Range | 39–90 | 23–92 | 23–92 | |||

| Male Gender | 466 | 66% | 742 | 69% | 1208 | 67% |

| Race, N (%) | ||||||

| White | 598 | 84% | 919 | 85% | 1517 | 85% |

| Black | 74 | 10% | 95 | 9% | 169 | 9% |

| Asian | 15 | 2% | 27 | 3% | 42 | 2% |

| Native American | 5 | 0·7% | 9 | 1% | 14 | 0·8% |

| Pacific Islander | 4 | 0·6% | 3 | 0·3% | 7 | 0·4% |

| Multi-Racial | 0 | 0% | 3 | 0·3% | 3 | 0·2% |

| Unknown | 15 | 2% | 23 | 2% | 38 | 2% |

| Hispanic, N (%) | 16 | 2% | 30 | 3% | 46 | 3% |

| Performance Status, N (%)2 | ||||||

| 0 | 199 | 28% | 275 | 25% | 474 | 26% |

| 1 | 499 | 70% | 743 | 69% | 1242 | 69% |

| 2 | 13 | 2% | 61 | 6% | 74 | 4% |

| Smoking History, N (%) | ||||||

| Current | 243 | 34% | 375 | 35% | 618 | 35% |

| Former | 437 | 61% | 665 | 62% | 1102 | 62% |

| Never | 31 | 4% | 39 | 4% | 70 | 4% |

| Prior Lines of Treatment for Stage IV/Recurrent Disease3 | ||||||

| 0 or 1 | 521 | 73% | 886 | 82% | 1407 | 79% |

| 2 | 132 | 19% | 122 | 11% | 254 | 14% |

| 3 or more | 58 | 8% | 71 | 7% | 129 | 7% |

| Weight Loss in Past 6 Months, N (%) | ||||||

| <5% or Weight Gain | 513 | 72% | 759 | 70% | 1272 | 71% |

| 5 – <10% | 103 | 14% | 195 | 18% | 298 | 17% |

| 10 – <20% | 81 | 11% | 110 | 10% | 191 | 11% |

| ≥20% | 12 | 2% | 10 | 1% | 22 | 1% |

| Unknown | 2 | 0·3% | 5 | 0·5% | 7 | 0·4% |

| NCTN Group, N (%)4 | ||||||

| SWOG | 322 | 45% | 567 | 53% | 889 | 50% |

| ALLIANCE | 167 | 23% | 209 | 19% | 376 | 21% |

| ECOG-ACRIN | 144 | 20% | 170 | 16% | 314 | 18% |

| NRG | 72 | 10% | 121 | 11% | 193 | 11% |

| CCTG | 6 | 0·8% | 12 | 1% | 18 | 1% |

| Type of Site, N (%) | ||||||

| Community (NCORP) | 262 | 37% | 424 | 39% | 686 | 38% |

| Member | 237 | 33% | 367 | 34% | 604 | 34% |

| Lead Academic | 212 | 30% | 288 | 27% | 500 | 28% |

Pre-screening was added to the study May 26, 2015, 11 months after activation.

Prior to December 18, 2015 PS 0–2 was allowed, after then, only PS 0–1 was allowed.

Prior to May 2015, the study was a second-line only trial allowing only 0 or 1 prior lines of therapy for stage IV or recurrent disease to be screened.

The Canadian Cancer Trials Group (CCTG) participated between December 18, 2015 and July 12, 2018, closing the study due to challenges with drug distribution across the US-Canadian border.

Figure 3.

Overall Survival from Time of Sub-study Assignment by Screening Type

Six hundred fifty-five patients registered to a sub-study (218 to biomarker-driven, 437 to non-match) and 31 patients registered to a new sub-study after progression on a prior sub-study (Figure 1). Nine sub-studies (three non-match, six biomarker-driven) were activated and their timelines depicted in Figure 2. Five biomarker-driven sub-studies were closed at their interim analysis for lack of activity (with approximately 20 patients evaluable for response in the primary analysis population in each sub-study), and one biomarker-driven sub-study was closed due to discontinuation of development of the drug (Table 2). Of the non-match sub-studies: durvalumab was closed to accrual to open the nivolumab/ipilimumab study which closed at an interim analysis for futility (at 50% information); the acquired resistance cohort of durvalumab/tremelimumab was closed at the interim for futility (at 20 patients evaluable for response); and the primary resistance cohort was closed early due to feasibility concerns; the study eligibility required single agent checkpoint inhibitor therapy as the most recent line of therapy preceded by platinum-based chemotherapy. In contrast to when the study was conceived of, very few patients receive this sequence of therapies at the time of study closure. A summary of the scientific justification for the sub-studies is included in the Supplementary Materials (Appendix pg. 2–4).

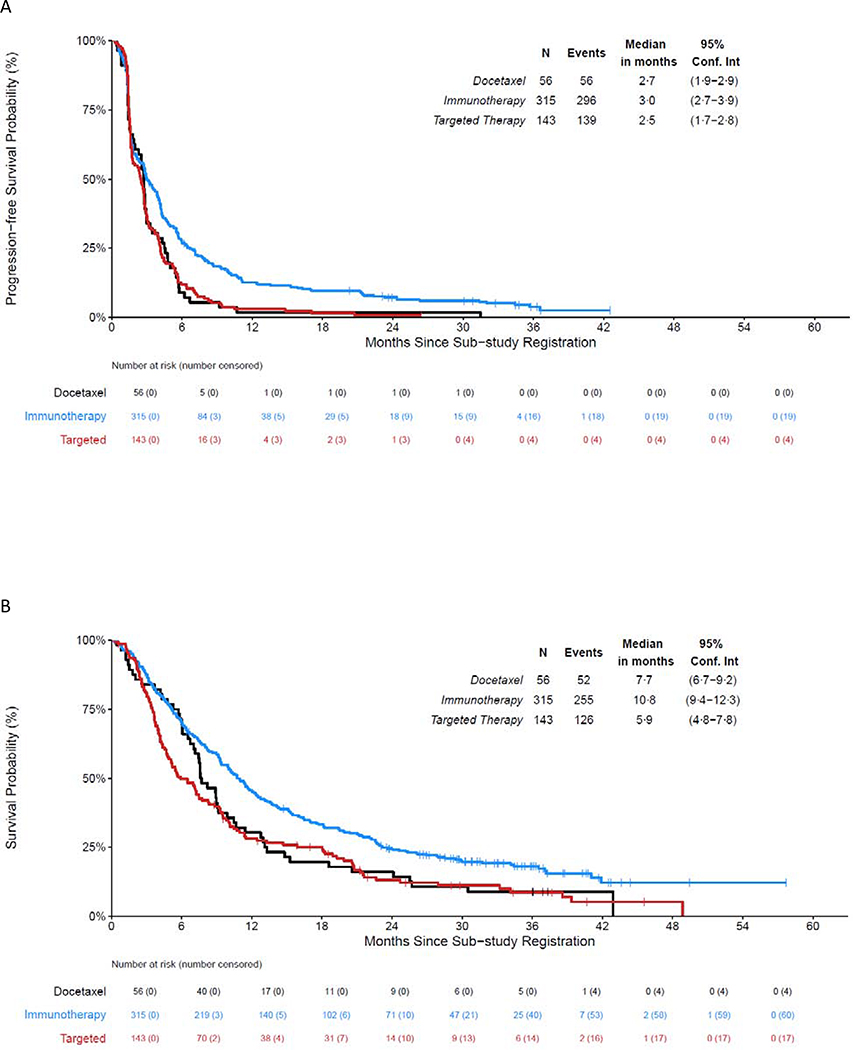

Across the sub-studies, 143 eligible patients were registered to receive a molecularly targeted treatment as their first line of therapy within Lung-MAP, 56 eligible patients were randomized to docetaxel prior to closure of those arms, and 315 anti-PD-(L)1-naïve eligible patients were registered to receive an anti-PD-(L)1 therapy (durvalumab, nivolumab, or nivolumab/ipilimumab) as their first line of therapy within Lung-MAP. There were ten (7%) of 143 patients whose disease responded to molecularly-targeted therapy, three (5%) of 56 responded to docetaxel, and 53 (17%) of 315 responded to anti-PD-(L)1 therapy in the immune checkpoint inhibitor-naïve setting. Figure 4 depicts PFS and OS from sub-study registration by treatment group, with a median (IQR) follow-up among patients still alive (N=81) of 32 (25–37) months. Median PFS was 2·5 months (95% CI: 1·7–2·8) for the targeted therapy arms, 2·7 (95% CI: 1·9–2·9) for the docetaxel arms, and 3·0 months (95% CI: 2·7–3·9) for the anti-PD-(L)1-containing arms. Median OS was 5·9 months (95% CI: 4·8 – 7·8) for the targeted therapy arms, 7·7 months (95% CI: 6·7 – 9·2) for the docetaxel arms, and 10·8 months (95% CI: 9·4 – 12·3) for the anti-PD-(L)1-containing arms.

Figure 4. Overall Survival from Time of Sub-study Registration for Molecular Targeted Therapies, Immunotherapies and Chemotherapy.

A: Progression-free Survival from the Time of Sub-study Registration by Treatment Type

B: Overall Survival from the Time of Sub-study Registration by Treatment Type

Discussion

With Lung-MAP (S1400) we successfully established an infrastructure to evaluate molecularly targeted therapies in genomically-defined subgroups of lung cancer and implemented the first Biomarker-driven Master Protocol within the NCI. We demonstrated that 1) comprehensive, centralized genomic screening using a commercially-available NGS platform is feasible in a diverse patient population, 2) Biomarker-Driven Master Protocols conducted within the NCTN are attractive to industry partners, 3) a series of biomarker-driven studies can be conducted simultaneously, even in uncommon genotypes, to efficiently assess drug activity, 4) the “non-match” option was essential, and 5) this approach is amenable to a drug registration-compliant strategy. Moreover, as part of the precision-medicine initiative within the NCI, the NCTN provided far-reaching patient access with the largest percentage of accrual coming from community sites or the VA system. The public-private partnership which engaged broader experience to conduct a complicated study infrastructure was essential. Most significantly, we addressed research questions that may not have otherwise been answered and included patient populations that may not have otherwise been able to participate in investigational studies of biomarker-driven therapies.

Master protocols present both opportunities and challenges. Conduct of a complex Biomarker-Driven Master Protocol requires adaptability as well as constant and intensive efforts by all partners. A comprehensive communications plan included bi-weekly leadership teleconferences and monthly teleconferences for each of the subcommittees (drug selection; sub-study chairs; site coordinators; accrual enhancement; statistical, data management, information technology, and protocol operations). Additional oversight, staff support, and operational efficiencies were needed to shepherd sub-studies through their entire life cycle. Extensive outreach to investigators, site coordinators, and patients through newsletters, study materials, videos, webinars, presentations at scientific conferences, and NCTN group meetings, established and maintained engagement in the study. A “site coordinators committee” addressed challenges of implementation and informed study conduct. An “accrual enhancement committee” developed and maintained educational and outreach materials.

Inclusion of the pre-screening option was an attractive option to both patients and physicians allowing for a patient and their physician to determine the optimal time for that patient to be screened. Notably, the comparison of survival from sub-study assignment (Figure 3) does not capture all of the benefit. With pre-screening, sites have ample time to locate and evaluate tissue for adequacy or to order a fresh biopsy, as needed. It allows for time to do the necessary tests and procedures to evaluate the patient for eligibility criteria, and it all can be done in a less stressful time when the patient is receiving therapy versus having just learned their prior therapy was no longer effective. In terms of study conduct, this option does have the detraction that fewer pre-screened patients than those screened at progression enrolled to their assigned sub-study which increases the relative costs of screening this population.

While the non-match sub-studies likely would have been more efficiently conducted had they had been run independently, the non-match sub-study option has been essential to Lung-MAP. Importantly, this option makes the biomarker-matched sub-studies feasible. In this aggressive disease setting it was essential that all screened patients had an option for participation in a sub-study even if they did not have one of the matching biomarkers. That said, inclusion of non-match sub-studies in Lung-MAP have value independent of their roll in facilitating the biomarker-driven studies. A benefit to evaluation of non-match therapies within Lung-MAP is that all patients have the full NGS results, allowing for retrospective assessment of potential biomarkers for treatment activity. The goal is to translate all studies in unselected populations into biomarker-selected subgroups.

A potential challenge for the evaluation of therapies within the non-match setting is the definition of the patient population. By definition, the non-match studies include patients who are not eligible for one of the biomarker-driven sub-studies. This population can vary during the conduct of the study based on accruing biomarker-driven sub-studies but is also likely not a natural definition of a population. If there is no clear reason that the excluded biomarker subgroups would benefit differentially from the non-match therapy, an argument could be made for assuming the results apply to these populations. However, regulatory agencies may find it challenging to define the label and conversations are certainly needed upfront to discuss the subtleties and interpretation of the data at the end of study, if being used for regulatory approval.

A major criticism of Lung-MAP (S1400) is that the investigated targeted therapies failed to demonstrate activity. We expected that this squamous lung cancer would be a particularly challenging disease setting given its genomic complexity and tumor mutational burden. 28 Concurrent with evaluation in Lung-MAP (S1400), all evaluated drug targets were under study in many smaller trials. Additionally, all targets with the exception of c-MET received FDA approval for drugs in class, subsequent to evaluation within Lung-MAP (S1400). Lung-MAP (S1400) allowed for a more definitive statement regarding the utility of these drug targets in lung cancer- something that would have been much more challenging without the master protocol. Therefore, while Lung-MAP has not had successes in establishing new treatments, it has also prevented prolonged evaluation of ineffective drug targets in lung cancer.

Lung-MAP does have limitations. The FMI NGS platform may not be the best biomarker for all therapies and bridging studies may be required if a therapy for regulatory approval. As all biomarker studies are within biomarker-selected populations, the studies cannot differentiate between prognostic and predictive biomarkers, necessitating data from outside the trial to support a predictive biomarker interpretation. But, by far the greatest challenge encountered in Lung-MAP was the rapid approval of anti-PD-(L)1 therapies across various indications in SqNSCLC.29 In response and crucial to the success of a Biomarker-Driven Master Protocol, Lung-MAP (S1400) efficiently implemented major revisions which included changes in eligibility, statistical designs, and the addition of an option to pre-screen patients during their first-line treatment. The changes implemented in Lung-MAP (S1400) demonstrated how a biomarker-driven master protocol can be self-sustaining and adaptable to scientific advancements. It follows that the most important lesson learned during the conduct of Lung-MAP was that Biomarker-Driven Master Protocols must be nimble and incorporate new science quickly. To do so requires a continuous stream of collaborations with the pharmaceutical industry and an active and engaged group of academic investigators for the continual development of new sub-studies.

Lung-MAP is not alone in the Master Protocol space though it was among the first. For example, within the NCTN, the ALCHEMIST trial is evaluating adjuvant targeted therapy in biomarker defined subgroups of lung cancer for therapies known to be effective in the advanced setting, the NCI-MATCH trial evaluated targeted therapy/biomarker pairs in a histology agnostic approach. The FOCUS4 trial evaluated molecularly targeted therapies in colorectal cancer, and the National Lung Matrix trial is evaluating targeted therapies for NSCLC. The SHIVA and MOSCATO 01 studies evaluated the strategy of assigning treatment based on molecular alterations. Each of these “master protocols” have a slightly different design and set of objectives.12–20 Relative to other master protocols being conducted in lung cancer, the Lung-MAP trial was created to evaluate signals of activity but also to be a pathway for regulatory approval by the United States FDA of targeted therapy/biomarker pairs. Our approach for designs for regulatory approval has been United States centric; while standard statistical designs were used within Lung-MAP, it is always possible that other regulatory bodies might view these data differently.

While the Lung-MAP (S1400) screening protocol and its associated sub-studies are completed, the Lung-MAP study continues. In early 2019, a new screening protocol (named LUNGMAP) was implemented expanding eligibility to all histologic types of NSCLC. Additionally, the new screening protocol implemented circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) testing for the subset of patients using a fresh tissue biopsy for screening with the goal to evaluate if ctDNA could be used as part of the upfront biomarker screening on Lung-MAP. All new sub-studies include ctDNA at baseline and on-study timepoints. Lung-MAP (S1400) patients may participate in our new studies. With this change, the primary pursuit of Lung-MAP to evaluate molecularly-targeted therapies in biomarker-defined subgroups was augmented to include the pursuit of immunotherapy combinations to overcome resistance to anti-PD-(L)1 therapy. Motivation for these changes was twofold: firstly, an infrastructure to evaluate targeted therapies for rare alterations in previously-treated non-squamous NSCLC was needed, and secondly, a clear unmet need in lung cancer is treatment for patients with anti-PD-(L)1-refractory/relapsed disease. This new protocol goes beyond histology to evaluate targeted and immune-therapies in NSCLC. With multiple sub-studies currently accruing and a robust pipeline of regimens in development, Lung-MAP remains true to its original vision to expeditiously improve treatment options for our patients with lung cancer.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

The Lung Cancer Master Protocol (Lung-MAP) was conceived of to address an unmet need to improve treatment options for patients with previously-treated stage IV or recurrent squamous cell lung cancer. When Lung-MAP was initiated in 2014 the standard of care options for squamous patients were platinum-based chemotherapy for first-line treatment and limited choice chemo-monotherapy for previously-treated patients with no targeted therapy options. In 2012, the Cancer Genome Atlas reported on the characterization of genomic alterations present in squamous cell lung cancers. The natural resulting question was could targeted therapies in biomarker-defined subgroups in squamous cell lung cancer be discovered in this population. However, a major concern existed regarding the feasibility of screening for sets of potentially rare alterations in an efficient way to minimize delays to start of treatment and to efficiently evaluate these targeted therapies. There also was a need to address care delivery disparities and bring these agents to the community and rural sites. Importantly, many of these mutations are rare comprising 5–15% of patients making it essential to develop a master protocol which would provide a screening umbrella to make allow us to answer this important clinical question. The Lung Master Protocol was conceived of to address these needs.

Added value of this study

The Lung-MAP study was the first master protocol launched within the National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN) of the National Cancer Institute. The trial demonstrated that biomarker-driven master protocols are feasible within an aggressive disease setting such as previously-treated advanced squamous lung cancers, that the infrastructure of the NCTN combined with unique public-private partnership enhanced the functioning and feasibility of conduct of the study, and that the infrastructure of a biomarker-driven master protocol could provide efficient answers to the activity of targeted therapies in rare populations. Equally of import, the Lung-MAP trial established a road map as to how to conduct master protocols within public and private settings and the lessons from the study and study conduct will continue to inform other such efforts in a variety of settings, oncology and otherwise.

Implications of all the available evidence

The first chapter of Lung-MAP evaluated therapeutic options for previously-treated advanced squamous lung cancers. It demonstrated that the discovery of targeted therapies is a challenging endeavor however important to pursue. Lung-MAP continues, now evaluating targeted therapies in all histologic types of advanced non-small cell lung cancers. The revised study also includes an additional focus on treatment options for patients with immune-checkpoint inhibitor refractory disease, an area of high unmet need. The Lung-MAP trial will continue to provide an infrastructure to evaluate investigational therapies and to learn more about how best to treat these types of lung cancers.

Acknowledgements:

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health CA180888, CA180819, CA180820, CA180821, CA180868, CA189858, CA189821, CA189830, CA239767, CA189971, CA180826, CA180828, CA180846, CA180858; and by AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Genentech and Pfizer through the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health, in partnership with Friends of Cancer Research.

As with any study, the set of persons listed as authors does not represent the full set of people involved in the successful implementation and conduct of a trial. Lung-MAP is a major endeavor and we would like to acknowledge the efforts of all the investigators who lead the efforts to conduct our sub-studies, the physicians enrolling patients onto the study, the vast members of the statistical and data management center for SWOG Cancer Research Network who participated in the build and running of the study, members of the SWOG operations and Group Chair’s Office who have spent uncountable hours making Lung-MAP a success, but most of all, to the patients who participated in this novel study. Without this full team of people, we could not have achieved what we have with Lung-MAP.

Funding National Institutes of Healthand by AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Genentech and Pfizer through the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health..

Declaration of Interests

MWR reports grants from NIH, grants from SWOG/Hope Foundation, during the conduct of the study; LS reports grants from Merck, personal fees from Boehringer, grants from Pfizer, grants from Roche, personal fees from Regeneron, outside the submitted work; PCM reports personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from Guardant Health, outside the submitted work; FRH reports other support from Merck, other from BMS, other from Daiichi, other from Genentech, other from Lilly/Loxo, other from Novartis, other from OncoCyte, other from Amgen, grants from Biodesix, grants from Mersana, grants from Amgen, grants from Rain Therapeutics, grants from Abbvie, outside the submitted work;DW has no disclosure; MLL reports grants from NIH, grants from SWOG/Hope Foundation, during the conduct of the study; DRG reports grants and other support from Amgen, other from AstraZeneca, other from Boehringer-Ingelheim, other from Guardant Health, other from Inivata, other from IO Biotech, grants and other from Merck, other from OncoCyte, grants and other from Roche-Genentech, other from Ocean Genomics, outside the submitted work; SR reports grants and other from Amgen, other from Abbvie, grants and other from BMS, other from Genentech/Roche, grants and other from Merck, grants and other from Astra Zeneca, grants and other from Takeda, grants from Tesaro, grants from Advaxix, outside the submitted work; VAP reports that she is currently an employee of Pfizer, the work was completed while she was an employee of MD Anderson; JB reports personal fees from astrazeneca, outside the submitted work; CM reports no disclosures; EV reports personal fees from AbbVie, personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Biolumina, personal fees from BMS, personal fees from Celgene, personal fees from Eli Lilly, personal fees from EMD Serono, personal fees from Genentech, personal fees from Merck, personal fees from Regeneron, personal fees from Novartis, outside the submitted work; NL has no disclosures; KM, JM and JM reports grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), during the conduct of the study; LH has no disclosures; VAM reports other support from Foundation Medicine, other from EQRx, other from Revolution Medicines, outside the submitted work; SA and EVS have no disclosures; CS reports other support from Foundation for the National Institutes for Health, during the conduct of the study; SM and BS have no disclosures; KK reports grants and personal fees from AbbVie, personal fees from AstraZeneca, grants and personal fees from Bristol Meyers Squibb, grants and personal fees from Genentech, personal fees from Pfizer, outside the submitted work; CDB reports grants from NCI, grants and other from FNIH, grants from Friends of Cancer Research, during the conduct of the study; RSH reports personal fees from Abbvie Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from ARMO Biosciences, personal fees and other from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Biodesix, personal fees from Bolt Biotherapeutics, personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, personal fees and other from Eli Lilly and Company, personal fees from EMD Serrano, personal fees and other from Genentech/Roche, personal fees from Genmab, personal fees from Halozyme, personal fees from Heat Biologics, personal fees from IMAB Biopharma, personal fees from Immunocore, personal fees from Infinity Pharmaceuticals, other from Junshi Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Loxo Oncology, personal fees and other from Merck and Company, personal fees from Midas Health Analytics, personal fees from Mirati Therapeutics, personal fees from Nektar, personal fees from Neon Therapeutics, personal fees from NextCure, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Sanofi, personal fees from Seattle Genetics, personal fees from Shire PLC, personal fees from Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Symphogen, personal fees from Takeda, personal fees from Tesaro, personal fees from Tocagen, outside the submitted work.

Footnotes

Data Sharing

The Lung-MAP (S1400) master protocol and all of the sub-studies conducted within the master protocol were partially funded by the United States National Cancer Institute and conducted by the SWOG Cancer Research Network, one of the National Clinical Trials Network Groups. The policies and procedures for requesting data is available at https://www.swog.org/sites/default/files/docs/2019-12/Policy43_0.pdf. Study data is/will be available for sharing as soon as the primary publication for each study has been published. Additionally, data from randomized phase III studies are available through the NCI’s data archives.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Herbst RS, Morgensztern D, Boshoff C. The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature 2018; 553: 446–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roskoski R Jr, Properties of FDA-approved small molecule protein kinase inhibitors. Pharmacol Res 2019; 144: 19–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morgensztern D, Waqar S, Subramanian J, Gao F, Govindan R. Improving survival for stage IV non-small cell lung cancer: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results survey from 1990 to 2005. J Thorac Oncol 2009; 4: 1524–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gandara DR, Hammerman PS, Sos ML, Lara PN Jr., Hirsch FR. Squamous cell lung cancer: from tumor genomics to cancer therapeutics. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21: 2236–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive genomic characterization of squamous cell lung cancers. Nature 2012; 489: 519–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frampton GM, Fichtenholtz A, Otto GA, et al. Development and validation of a clinical cancer genomic profiling test based on massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nat Biotechnol 2013; 31: 1023–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herbst RS, Gandara DR, Hirsch FR, et al. Lung Master Protocol (Lung-MAP)-A biomarker-driven protocol for accelerating development of therapies for squamous cell lung cancer: SWOG S1400. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21: 1514–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woodcock J, LaVange LM. Master protocols to study multiple therapies, multiple diseases, or both. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redman MW, Allegra CJ. The master protocol concept. Semin Oncol 2015; 42: 724–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cecchini M, Rubin EH, Blumenthal GM, et al. Challenges with novel clinical trial designs: master protocols. Clin Cancer Res 2019; 25: 2049–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malik SM, Pazdur R, Abrams JS, et al. Consensus report of a joint NCI thoracic malignancies steering committee: FDA workshop on strategies for integrating biomarkers into clinical development of new therapies for lung cancer leading to the inception of “master protocols” in lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2014; 9: 1443–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim ES, Herbst RS, Wistuba II, et al. The BATTLE trial: personalizing therapy for lung cancer. Cancer Discov 2011; 1: 44–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Middleton G, Crack LR, Popat S, et al. The National Lung Matrix Trial: translating the biology of stratification in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2015; 26: 2464–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coyne GO, Takebe N, Chen AP. Defining precision: The precision medicine initiative trials NCI-MPACT and NCI-MATCH. Curr Probl Cancer 2017; 41: 182–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massard C, Michiels S, Ferte C, et al. High-throughput genomics and clinical outcome in hard-to-treat advanced cancers: results of the MOSCATO 01 trial. Cancer Discov 2017; 7: 586–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barker AD, Sigman CC, Kelloff GJ, Hylton NM, Berry DA, Esserman LJ. I-SPY 2: an adaptive breast cancer trial design in the setting of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2009; 86: 97–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen AP, Eljanne M, Harris L, Malik S, Seibel NL. National Cancer Institute basket/umbrella clinical trials: MATCH, Lung-MAP, and beyond. Cancer J 2019; 25: 272–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stockley TL, Oza AM, Berman HK, et al. Molecular profiling of advanced solid tumors and patient outcomes with genotype-matched clinical trials: the Princess Margaret IMPACT/COMPACT trial. Genome Med 2016; 8: article 109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adams R, Brown E, Brown L, et al. Inhibition of EGFR, HER2, and HER3 signalling in patients with colorectal cancer wild-type for BRAF, PIK3CA, KRAS, and NRAS (FOCUS4-D): a phase 2–3 randomised trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;3(3):162–171. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30394-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Tourneau C, Paoletti X, Servant N, et al. Randomised proof-of-concept phase II trial comparing targeted therapy based on tumour molecular profiling vs conventional therapy in patients with refractory cancer: results of the feasibility part of the SHIVA trial. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(1):17–24. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foundation Medicine Inc. Foundation One CDx. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf17/P170019C.pdf, 2017.

- 22.Aggarwal C, Redman MW, Lara PN Jr., et al. SWOG S1400D (NCT02965378), a phase II study of the fibroblast growth factor receptor inhibitor AZD4547 in previously treated patients with fibroblast growth factor pathway-activated stage IV squamous cell lung cancer (Lung-MAP substudy). J Thorac Oncol 2019; 14: 1847–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bazhenova L, Redman MW, Gettinger SN, et al. A phase III randomized study of nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus nivolumab for previously treated patients with stage IV squamous cell lung cancer and no matching biomarker (Lung-MAP Sub-Study S1400I, NCT02785952). J Clin Oncol 2019; 37 (suppl): abstr 9014. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edelman MJ, Redman MW, Albain KS, et al. SWOG S1400C (NCT02154490)-A phase II study of palbociclib for previously treated cell cycle gene alteration-positive patients with Stage IV squamous cell lung cancer (Lung-MAP substudy). J Thorac Oncol 2019; 14: 1853–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langer CJ, Redman MW, Wade JL 3rd, et al. SWOG S1400B (NCT02785913), a phase II study of GDC-0032 (taselisib) for previously treated PI3K-positive patients with stage IV squamous cell lung cancer (Lung-MAP sub-study). J Thorac Oncol 2019; 14: 1839–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Owonikoko TK, Redman MW, Byers LA, et al. A phase II study of talazoparib (BMN 673) in patients with homologous recombination repair deficiency (HRRD) positive stage IV squamous cell lung cancer (Lung-MAP Sub-Study, S1400G). J Clin Oncol 2019; 37 (suppl): abstr 9022. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waqar SN, Redman MW, Arnold SM, et al. Phase II study of ABBV-399 (Process II) in patients with C-MET positive stage IV/recurrent lung squamous cell cancer (SCC): LUNG-MAP sub-study S1400K (NCT03574753). J Clin Oncol 2019; 37 (suppl): abstr 9075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willis C, Fiander M, Tran D, et al. Tumor mutational burden in lung cancer: a systematic literature review. Oncotarget 2019; 10: 6604–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 123–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.