Abstract

The prevalence of hypertension increases with advancing age, due primarily to increases in systolic blood pressure. Systolic hypertension is the most common form of hypertension in individuals over 50 years of age and reflects pathologic decreases in arterial compliance. Systolic blood pressure elevation is a more important risk factor for cardiovascular disease than is diastolic blood pressure elevation. Stage 2 hypertension, defined as blood pressure ≥160/100 mm Hg, is often found in older persons, who are at highest risk for cardiovascular events. In this clinical review, hypertension experts utilize a case study to provide a paradigm for treating older patients with stage 2 hypertension.

Hypertension, or high blood pressure (BP), affects at least 65 million Americans—31% of all adults—and is a major independent risk factor for cardiovascular (CV) morbidity and mortality. 1 A disproportionate number of individuals with high BP are older adults; approximately 81 % of adults with high BP are 45 years of age and older, although this same age group represents about 46% of the population. 1 Increasing age is associated with changing patterns of BP such that in patients with hypertension, systolic BP (SBP) continues to rise progressively in both men and women throughout adult life, while diastolic BP (DBP) tends to increase until approximately age 55 years, level off over the next decade, and either remain the same or decline somewhat thereafter. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 By age 75 years, almost all hypertensive patients have systolic hypertension. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2 has shown that many of these individuals have SBP of ≥160 mm Hg, a level that triples the risk of CV events. The Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) 4 defines stage 2 hypertension as BP ≥160/100 mm Hg. Unfortunately, BP control is particularly poor among older hypertensive patients, who are at highest risk for CV events. 5

Controlling systolic hypertension is now recognized as the more important factor for CV and renal event risk reduction. This is due in part to the greater difficulty in achieving SBP control and the understanding that the majority of patients older than age 50 will reach DBP goal once SBP goal is achieved. 4

Starting at about age 50, SBP is the strongest predictor of CV disease (CVD) and premature death. 3 , 6 A meta‐analysis of randomized, controlled clinical trials including more than one million individuals aged 40–69 years revealed that the absolute risk of CVD mortality doubled with each 20 mm Hg increase in SBP above 115 mm Hg. 7 Nevertheless, a random survey of 2500 patients enrolled in a large health maintenance organization revealed that most hypertensive individuals continue to perceive DBP, rather than SBP, as a more important risk factor for CVD. 8

The relationship between increasing levels of BP and all CV events is strong, continuous, and independent of other risk factors, including age and the presence of other CVDs. 4 Data from numerous randomized, controlled trials have proven that BP‐lowering therapy is associated with substantial reductions in stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), renal failure, and heart failure. 4 Yet, despite the clear benefits, BP control is far from adequate. According to data from the most recent NHANES, 5 only about half of the individuals in the United States taking medication for hypertension have BP levels <140/90 mm Hg. The primary reason for inadequate BP control is the use of less than optimal treatment regimens. Results from large placebo‐controlled trials have shown that two or more antihypertensive agents are typically required to achieve target BP goals. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16

When treating a patient with stage 2 hypertension, the clinician must determine the appropriate BP goal, select the initial antihypertensive regimen, and modify that regimen, as necessary, to achieve goal BP. The clinician should also consider the impact of the treatment regimen on both the patient's compliance with therapy and long‐term risk for CVD. A case study is used to illustrate the decision‐making process.

CASE STUDY

Clinical History

The patient is a 66‐year‐old man who arrives for a physical examination because he is “not feeling so great.” He was last seen for a routine visit 12 months previously. Prior to the diagnosis of both hypertension and hyperlipidemia about 7 years ago, he considered his health to be “excellent.” He is compliant with his current medications, which are hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) 25 mg/d, aspirin 81 mg/d, and atorvastatin 10 mg/d. He has no other significant medical or surgical history. His father died of an MI at age 59, and his mother, who is 89 years old, has hypertension and type 2 diabetes and recently had a stroke.

The patient, a retired physical education teacher, is married and has three grown children and four grandchildren. He is physically active; he plays golf and tennis and coaches his grandson's baseball team. He is concerned because he has noticed increasing fatigue and some shortness of breath. A former smoker, he quit more than 20 years ago. He drinks one to two beers daily. A work‐up has not revealed any clues for secondary hypertension. He does not have any symptoms of urinary outflow obstruction, he does not regularly use nonsteroidal analgesics, and he does not use pressor agents, such as nasal sprays.

Physical Examination

The patient is 5'10” tall, weighs 195 pounds, and his body mass index is 28 kg/m2. The balance of his physical examination is as follows:

-

•

BP: sitting BP, 168/80 mm Hg (right arm); standing BP, 164/88 mm Hg. BP is 4 mm Hg higher in the right arm than in the left arm.

-

•

Fundoscopic examination: no papilledema, normal vessels, no exudates

-

•

No gingival hypertrophy; carotids and thyroid normal

-

•

Heart: heart rate, 72 bpm; normal S1 and S2; no murmur; S4 present

-

•

Lungs: no rales or wheezes

-

•

Abdomen: soft, no masses, no tenderness, no hepatomegaly, no bruits; urinary bladder not distended

-

•

Peripheral pulses: present and equal bilaterally; trace pedal edema bilaterally

Laboratory Findings

The results of nonfasting laboratory tests are as follows:

-

•

Complete blood cell count: normal

-

•

Chemistry panel: glucose, 102 mg/dL; blood urea nitrogen, 17 mg/dL; creatinine, 1.1 mg/dL; sodium, 144 mmol/L; potassium, 3.2 mmol/L; chloride, 100 mmol/L; bicarbonate, 34 mmol/L

-

•

Lipids: total cholesterol, 198 mg/dL; low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, 120 mg/dL; high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, 45 mg/dL; triglycerides, 168 mg/dL

-

•

Urinalysis: trace protein; negative for sugar, red blood cells, and white blood cells

-

•

Electrocardiogram (ECG): normal sinus rhythm with evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy

Assessment

This 66‐year‐old patient has a number of important risk factors for CVD. First, his age places him at a three‐ to four‐fold increased risk for CVD. He has signs of left ventricular hypertrophy on ECG. Proteinuria (even trace) represents a major renal and CVD risk factor. His symptoms of fatigue, shortness of breath, and slight pedal edema suggest the possibility of heart failure, which must be evaluated promptly. His family history is notable, with a paternal fatal MI and maternal hypertension, diabetes, and stroke. Although he remains active and is not obese, his body mass index indicates that he is overweight. His electrolytes are within the noncritical range, but the low potassium level cannot be ignored. It is most likely due to diuretic‐related potassium depletion, but may be a clue to secondary hypertension. The presence of edema and hypokalemia suggest that secondary hyperaldosteronism, perhaps due to heart failure, must be ruled out.

Plan for Management

The patient's paramount problem is inadequately treated stage 2 hypertension. He should also be evaluated further for evidence of hypertensive target‐organ damage, including an echocardiogram to assess for evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy and heart failure and a urine albumin‐creatinine ratio to confirm the extent of proteinuria. A fasting lipid profile is recommended at his next visit, followed by pharmacologic therapy should the profile prove abnormal. The patient's hypokalemia also requires follow‐up and treatment.

Management of hypertension should always include both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions. This patient may need significant education about his prognosis and encouragement to follow the treatment plan in order to bring his BP under control quickly and reduce his risk of a cardiac event or stroke in the short term and the development of heart failure and kidney disease in the long term. Nonpharmacologic measures would include a dietary analysis and a plan for gradual weight loss with a low‐sodium diet such as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) and maintenance of weight loss through diet and regular exercise. Individuals with chronically low blood levels of potassium may have an underlying problem with magnesium deficiency. Where this is true, magnesium supplements may help correct the potassium deficiency.

Diuretic monotherapy is considered appropriate for patients with uncomplicated hypertension 4 ; however, even at a higher dose, HCTZ is clearly inadequate to control this patient's BP. In some hypertensive patients, 15 , 17 , 18 high‐dose diuretic therapy has been shown to increase the risk of development of new‐onset diabetes. The patient's antihypertensive regimen should be changed to one that both brings his BP under control and has the greatest potential to reduce target‐organ damage and CVD risk. It is possible that diuretic therapy could cause the patient to develop hypokalemia 19 ; his low potassium level suggests the possibility of diuretic‐related potassium depletion. Because he has stage 2 hypertension (mean SBP, 168 mm Hg), which is >20 mm Hg over his goal of <140 mm Hg, a reasonable option would be to lower the dose of HCTZ from 25 mg/d to 12.5 mg/d and add one or two complementary agents at low doses. His BP should be monitored frequently until it is well controlled. Should the diuretic dosage be reduced, or a calcium channel blocker (CCB) be added to the regimen, then careful monitoring of the patient's edema will be necessary.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND RESEARCH FINDINGS FOR TREATING STAGE 2 HYPERTENSION

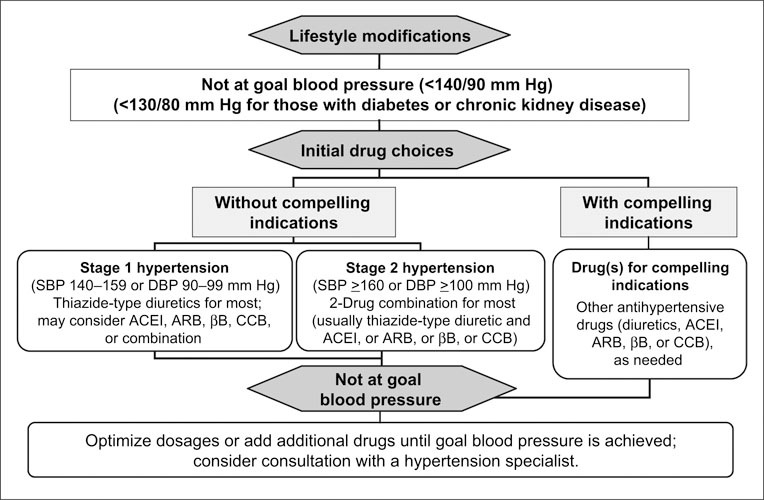

JNC 7 has promulgated the “20/10” rule, which states that in patients whose SBP or DBP is >20/10 mm Hg above goal BP, consideration should be given to initiating therapy with two agents (Figure I). 4 The JNC 7 report advises caution when initiating therapy with more than one agent in patients at risk for orthostatic hypotension, such as patients with diabetes, autonomic dysfunction, and in some older patients. 4

Figure 1.

Algorithm for the treatment of hypertension. SBP=systolic blood pressure; DBP=diastolic blood pressure; ACEl=angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB=angiotensin receptor blocker; βB=β blocker; CCB=calcium channel blocker. Reproduced with permission from Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–1252.4

The use of combination therapy generally produces greater BP reduction at lower doses of the component agents and often results in fewer adverse effects when compared with higher‐dose monotherapy. When complementary classes of antihypertensive agents are combined, their differing mechanisms of action serve to overcome the compensatory physiologic responses that may limit the BP‐lowering effects of a single agent. As a result, patients who do not reach goal BP during therapy with either of two individual agents as monotherapy frequently respond to a combination of lower doses of the two agents. 20 A meta‐analysis of placebo‐controlled trials of thiazide diuretics, β blockers, angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), and CCBs, given singly and in fixed‐dose combinations, found that combination low‐dose drug treatment, compared with monotherapy, increases efficacy and reduces adverse effects. 21

When a patient's SBP is >160 mm Hg, monotherapy will probably be inadequate for BP control. A fixed‐dose combination antihypertensive agent allows many patients with stage 2 hypertension to be treated successfully and conveniently with a single pill taken once daily. Lower doses of two drugs, compared with a higher dose of a single agent, often produce fewer dose‐dependent adverse events, thus potentially enhancing patient compliance.

An agent that blocks the renin‐angiotensin system (RAS) is recommended as a compelling indication in the antihypertensive regimen of high‐risk patients, including those with diabetes, heart failure, or renal disease, or patients who are post‐MI or stroke. 4 Fixed‐dose combination agents generally combine an agent that blocks the RAS with either a thiazide diuretic or a CCB; combinations utilizing a β blocker and a diuretic are also available (Table). Often a third agent is needed in these patients to bring BP under control. Optimal combinations of antihypertensive drugs typically involve the pairing of a sodium‐volume reducer with an RAS blocker, as can be seen in the selection of fixed‐dose, single‐capsule combination agents that have been developed and are available in the United States. 4 Some experts suggest an “AB/CD” rule, in which combination therapy is generally comprised of one drug from the AB category, representing ACE inhibitors, ARBs and β blockers; and one agent from the CD category, which includes CCBs, diuretics, and other sodium‐volume reducers. 22 , 23 Therefore, the most logical agents to be combined with an ACE inhibitor would be a diuretic or a CCB.

ACE inhibitors reduce BP primarily by inhibition of the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, a peptide hormone, which is the main effector of the RAS. Angiotensin II is a powerful vasoconstrictor that promotes sympathetic activation, aldosterone release, and renal salt and water reabsorption, among other effects that raise BP and increase risks for CVD. 24 Largely through blockade of angiotensin II, ACE inhibitors decrease vasoconstriction, sympathetic activation, and aldosterone release, thus lowering total peripheral resistance and decreasing renal sodium and fluid retention. 25 , 26 In addition, ACE inhibitors promote preservation of bradykinin, a potent vasodilator that contributes to the antihypertensive effects of ACE inhibition. 27

Diuretics are believed to lower BP generally by stimulation of diuresis‐natriuresis, resulting in reduction of plasma fluid, extracellular fluid volume, and sodium. 19 , 28 Long‐term diuretic therapy is also associated with a reduction in total peripheral resistance of unclear mechanism, contributing to its antihypertensive effect. 19 , 28

The main physiologic basis for adding a diuretic to an ACE inhibitor is that the sodium depletion induced by the diuretic will trigger counterregulatory activation of the RAS that will make BP more dependent on angiotensin II, and thus potentiate the efficacy of the ACE inhibitor. 29 , 30 The blunting of this counterregulatory response with ACE inhibition, particularly the inhibition of aldosterone release, also enhances the antihypertensive efficacy of the diuretic. 26 , 28 , 29 Furthermore, the mild natriuretic effect of ACE inhibitors adds to the sodium‐ and fluid‐volume reduction of diuretics. 29 , 30 Multiple studies have shown that adding a diuretic to an ACE inhibitor provides significant BP reduction compared to placebo 31 , 32 and adds significantly greater antihypertensive efficacy than component monotherapy, while reducing diuretic‐associated adverse events in elderly, white, and African‐American patients. 29 , 30 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 In addition, ACE inhibitor‐diuretic combination therapy with perindopril and indapamide produced significantly greater reductions in BP, stroke, and total major CV events, compared to perindopril monotherapy. 37

CCBs are potent antihypertensive agents that inhibit the flux of calcium ions into vascular smooth muscle and cardiac muscle, reducing peripheral vascular resistance and thereby lowering BP. The combination of a CCB and an ACE inhibitor has been shown to produce additive BP‐lowering effects as well as to reduce CV events in randomized clinical trials, including the large Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) trial. 9 , 38 , 39 , 40 This combination may have an important role in treating patients at high risk for target‐organ damage and CVD. 41 , 42 Particularly in patients with stage 2 hypertension, the combination of an ACE inhibitor and a CCB, with or without HCTZ, has been shown to produce additive BP‐lowering effects. In a multicenter, doubleblind, randomized trial, 41 the efficacy and safety of fixed‐dose ACE inhibitor—CCB combination therapy vs. CCB monotherapy was evaluated in 364 patients with stage 2 hypertension. The trial's protocol defined treatment success as a reduction in SBP of ≥25 mm Hg (if baseline SBP was ≤180 mm Hg) or a reduction in SBP of ≥32 mm Hg (if baseline SBP was ≥180 mm Hg). After 12 weeks, 74% of patients randomized to combination therapy achieved their BP goal, compared with 54% of those randomized to monotherapy (p<0.0001).

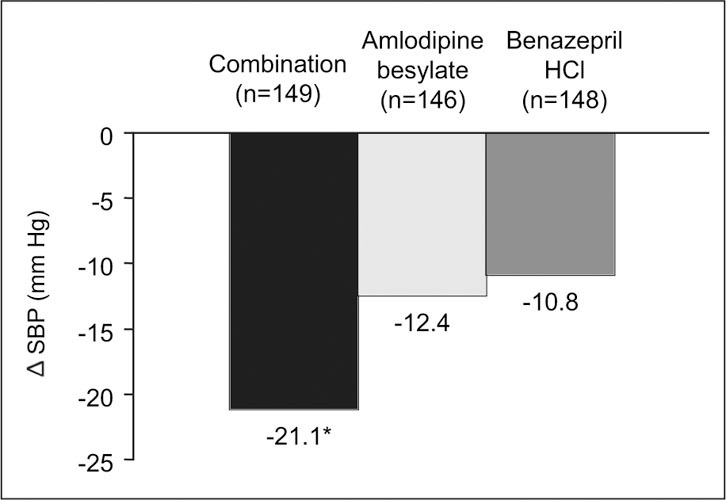

In a separate study, 42 24‐hour ambulatory BP monitoring was utilized to compare the fixed‐dose combination amlodipine besylate‐benazepril HCl with either of its two components (amlodipine besylate or benazepril HCl) in 443 patients aged 55 years and older with stage 2 hypertension (mean baseline sitting BP, 168.9±8.3/87.9±8.2 mm Hg). After 8 weeks of treatment, combination therapy was significantly more effective than either monotherapy treatment in reducing mean 24‐hour SBP (Figure 2), and 65% of patients in the combination group had BP controlled to <140/90 mm Hg, compared with 28% and 34% in the two monotherapy groups, respectively (p<0.0001).

Figure 2.

Reductions in 24‐hour ambulatory systolic blood pressure (SBP) in the intent‐to‐treat population in a comparison of a fixed‐dose combination (amlodipine besylate—benazepril HCl) with either of its two components. δ=change; *p<0.0001 for combination vs. both other treatments

More evidence of the benefits of an ACE inhibitor—CCB combination is anticipated from the results of the large Anglo‐Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial (ASCOT), 43 which was stopped early due to the occurrence of CV benefits in favor of the amlodipine‐perindopril therapy compared with atenolol‐bendroflumethiazide therapy. These benefits include significantly reduced risks of all‐cause mortality, CV mortality, CV events, stroke, and new‐onset diabetes in the patients who received the ACE inhibitor—CCB combination. 43

SUMMARY

Persons with either stage 1 or stage 2 hypertension have the same BP targets: <140/90 mm Hg or, for patients with diabetes or chronic kidney disease, <130/80 mm Hg. The “20/10” rule from the JNC 7 report always applies by definition to patients with stage 2 hypertension; therefore, in these patients, consider giving combination antihypertensive therapy in order to achieve BP control as rapidly as possible.

In this case review, the patient currently being treated with HCTZ 25 mg once daily has a sitting BP of 168/80 mm Hg. A look at his entire clinical picture reveals that he has a number of CVD risk factors, including evidence of target‐organ damage. If the patient adopts recommended lifestyle measures, and his BP is controlled with combination therapy, the risk of a CV or renal event will be substantially decreased. Further investigation and management of the patient's hypokalemia is important, as it may be due to diuretic therapy or to secondary hyperaldosteronism.

In conclusion, providing antihypertensive therapy and advising lifestyle changes are not sufficient interventions—it is necessary to bring the patient to the appropriate BP goal and to monitor BP at regular intervals to maintain BP control. Most patients will require two or more drugs to reach goal BP. Combination therapy plays an important role in bringing hypertensive patients to BP goal quickly. Fixed‐dose combination therapy may reduce adverse events associated with highdose monotherapy. Finally, fixed‐dose combination therapy provides a simpler, more convenient therapeutic regimen, which has the potential to improve medication compliance.

Disclosures: Dr. Materson serves as a consultant and speaker for Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation and other pharmaceutical companies. He has no financial interest such as stock ownership. Dr. Giles serves as a consultant and has received grants/ research support from Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation and other pharmaceutical companies. He has no financial interest such as stock ownership.

References

- 1. Fields LE, Burt VL, Cutler JA, et al. The burden of adult hypertension in the United States 1999 to 2000: a rising tide. Hypertension. 2004; 44:398–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Burt VL, Whelton P, Roccella EJ, et al. Prevalence of hypertension in the US adult population: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1991. Hypertension. 1995; 25:305–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Franklin SS, Larson MG, Khan SA, et al. Does the relation of blood pressure to coronary heart disease risk change with aging? The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2001; 103:1245–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003; 42:1206–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988–2000. JAMA. 2003; 290:199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stamler J, Stamler R, Neaton JD. Blood pressure, systolic and diastolic, and cardiovascular risks. US population data. Arch Intern Med. 1993; 153:598–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, et al., and the Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age‐specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta‐analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002; 360:1903–1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alexander M, Gordon NP, Davis CC, et al. Patient knowledge and awareness of hypertension is suboptimal: results from a large health maintenance organization. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2003; 5:254–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al., for the HOT Study Group. Effects of intensive blood‐pressure lowering and low‐dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. Lancet. 1998; 351:1755–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group . Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ. 1998; 317:703–713. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Estacio RO, Schrier RW. Antihypertensive therapy in type 2 diabetes: implications of the Appropriate Blood Pressure Control in Diabetes (ABCD) trial. Am J Cardiol. 1998; 82:9R–14R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hebert LA, Kusek JW, Greene T, et al., for the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Effects of blood pressure control on progressive renal disease in blacks and whites. Hypertension. 1997; 30:428–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schrier RW, Estacio RO, Esler A, et al. Effects of aggressive blood pressure control in normotensive type 2 diabetic patients on albuminuria, retinopathy and strokes. Kidney Int. 2002; 61:1086–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, et al., for the Collaborative Study Group. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin‐receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345:851–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high‐risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002; 288:2981–2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wright JT Jr, Bakris G, Greene T, et al., for the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension Study Group. Effect of blood pressure lowering and antihypertensive drug class on progression of hypertensive kidney disease: results from the AASK trial. JAMA. 2002; 288:2421–2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brown MJ, Palmer CR, Castaigne A, et al. Morbidity and mortality in patients randomised to double‐blind treatment with a long‐acting calcium‐channel blocker or diuretic in the International Nifedipine GITS study: Intervention as a Goal in Hypertension Treatment (INSIGHT). Lancet. 2000; 356:366–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Verdecchia P, Reboldi G, Angeli F, et al. Adverse prognostic significance of new diabetes in treated hypertensive subjects. Hypertension. 2004; 43:963–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sica DA. Diuretic‐related side effects: development and treatment. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2004; 6:532–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Materson BJ, Reda DJ, Williams D, for the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents. Lessons from combination therapy in Veterans Affairs studies. Am J Hypertens. 1996; 9:187S–191S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Law MR, Wald NJ, Morris JK, et al. Value of low dose combination treatment with blood pressure lowering drugs: analysis of 354 randomised trials. BMJ. 2003; 326:1427–1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brown MJ, Cruickshank JK, Dominiczak AF, et al., for the Executive Committee, British Hypertension Society. Better blood pressure control: how to combine drugs. J Hum Hypertens. 2003; 17:81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dickerson JE, Hingorani AD, Ashby MJ, et al. Optimisation of antihypertensive treatment by crossover rotation of four major classes. Lancet. 1999; 353:2008–2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Givertz MM. Manipulation of the renin‐angiotensin system. Circulation. 2001; 104:e14–e18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Weir MR. Impact of age, race and obesity on hypertensive mechanisms and therapy. Am J Med. 1991; 90:3S–14S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Waeber B. Fixed low‐dose combination therapy for hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2002; 4:298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cruden NL, Witherow FN, Webb DJ, et al. Bradykinin contributes to the systemic hemodynamic effects of chronic angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibition in patients with heart failure. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004; 24:1043–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lant AF. Evolution of diuretics and ACE inhibitors, their renal and antihypertensive actions—parallels and contrasts. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;23(suppl 1):27S–41S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Opie LH, Messerli FH. The choice of first‐line therapy: rationale for low‐dose combinations of an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor and a diuretic. J Hypertens Suppl. 2001; 19:S17–S21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chrysant SG. Fixed low‐dose drug combination for the treatment of hypertension. Arch Fam Med. 1998; 7:370–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chalmers J, Castaigne A, Morgan T, et al. Long‐term efficacy of a new, fixed, very‐low‐dose angiotensin‐converting enzymeinhibitor/diuretic combination as first‐line therapy in elderly hypertensive patients. J Hypertens. 2000; 18:327–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Guthrie R, Reggi DR, Plesher MM, et al., for the Fosinopril/Hydrochlorothiazide Investigators. Efficacy and safety of fosinopril/hydrochlorothiazide combinations on ambulatory blood pressure profiles in hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 1996; 9:306–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vlasses PH, Rotmensch HH, Swanson BN, et al. Comparative antihypertensive effects of enalapril maleate and hydrochlorothiazide, alone and in combination. J Clin Pharmacol. 1983; 23:227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Weinberger MH. Influence of an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor on diuretic‐induced metabolic effects in hypertension. Hypertension. 1983; 5:III132–III138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Weinberger MH. Blood pressure and metabolic responses to hydrochlorothiazide, captopril, and the combination in black and white mild‐to‐moderate hypertensive patients. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1985;7(suppl 1):S52–S55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Scholze J, Zilles P, Compagnone D. for the German Hypertension Study Group. Verapamil and trandolapril combination therapy in hypertension‐a clinical trial of factorial design. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998; 45:491–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. PROGRESS Collaborative Group . Randomised trial of a perindopril‐based blood‐pressure‐lowering regimen among 6,105 individuals with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2001; 358:1033–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sheinfeld GR, Bakris GL. Benefits of combination angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor and calcium antagonist therapy for diabetic patients. Am J Hypertens. 1999;12(suppl 1):80S–85S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tuomilehto J, Rastenyte D, Birkenhäger WH, for the Systolic Hypertension in Europe Trial Investigators. Effects of calcium‐channel blockade in older patients with diabetes and systolic hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1999; 340:677–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Epstein M, Bakris G. Newer approaches to antihypertensive therapy. Use of fixed‐dose combination therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1996; 156:1969–1978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jamerson KA, Nwose O, Jean‐Louis L, et al. Initial angiotensinconverting enzyme inhibitor/calcium channel blocker combination therapy achieves superior blood pressure control compared with calcium channel blocker monotherapy in patients with stage 2 hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2004; 17:495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Neutel JM, Smith DHG, Weber MA, et al. Initial combination therapy in older patients with systolic hypertension: results of the Systolic Evaluation of Lotrel Efficacy and Comparative Therapies (SELECT) study [abstract]. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17(5 pt 2):183A–184A. Abstract P‐409. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Blood pressure treatment could cut risk of strokes and heart attacks. Available at: http:www.ascotstudy.orggetdoc.php?id=88. Accessed March 17, 2005.