Abstract

Palpable dense and mobile subareolar tissue in the male breast defines the presence of gynecomastia. For the hypertension specialist, breast enlargement in men provides a clue to a secondary cause of hypertension or an adverse antihypertensive drug reaction. Hyperthyroidism, chronic renal failure, adrenal hyperplasia or tumors, amphetamine, cyclosporine, and anabolic steroids are secondary causes of hypertension associated with gynecomastia. Reserpine, methyldopa, and spironolactone are older drugs associated with gynecomastia; however, calcium antagonists (more commonly), angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, and α1 blockers may also be associated with this finding. Treatment is directed to removal of the underlying cause.

Gynecomastia is a physical finding that hypertensionologists need to assess in the routine evaluation of patients (Figure). Its presence may be indicative of a secondary cause of hypertension; antihypertensive medications are one of the most common causes of gynecomastia. 1 , 2 , 3

Figure 1.

A 53‐year‐old black male complains of left breast enlargement and tenderness. His blood pressure is 126/78 mm Hg and his creatinine is 2.0 mg/dL. His medications include amlodipine 10 mg q.d., doxazosin 8 mg q.d., and spironolactone/hydrochlorothiazide 25/25 mg q.d. Which of his medications potentially could contribute to symptoms and physical findings?

DEFINITION AND PREVALENCE

Gynecomastia is due to the proliferation of the glandular component of the male breast. Involvement may be unilateral or bilateral. Pain also may be present. How frequently it occurs depends on the definition used to define the presence of gynecomastia. 1 Using at least two centimeters of mobile, dense (but not hard) subareolar tissue, the prevalence is 36%‐65%. Among 306 American military personnel aged 17–58 years, the prevalence was 36%; whereas, among 214 American veterans aged 27–92 years, the prevalence was 65%. Clearly, obesity increases the difficulty of diagnosing gynecomastia.

CAUSES OF GYNECOMASTIA

Gynecomastia is considered to be due to alterations in the free androgen/estrogen ratio, where estrogen stimulates and androgen inhibits breast tissue development. Free estrogens levels may increase due to direct testicular or adrenal secretion, enhanced androgen aromatization, estrogen displacement from sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), decreased metabolism of estrogen, or direct exposure to estrogens or estrogen‐like compounds. Free androgen levels may decrease as a result of impaired secretion or synthesis, increased metabolism, or increased SHBG binding. Decreased androgen action may result from androgen displacement from receptor or impaired androgen receptor function. Gynecomastia occurs in neonates due to maternal estrogens and during puberty due to the dramatic increases in estrogen and androgen production. The prevalence is highest after age 50 years due to declining androgen levels and is associated with increased adipose tissue, which is an important site of aromatization of androgen to estrogen. Persistent gynecomastia of puberty, drugs, adrenal tumors, thyroid disease, renal disease, cirrhosis, malnutrition, primary and secondary hypogonadism, and testicular tumors are well known causes. 1

SECONDARY CAUSES OF HYPERTENSION

Hyperthyroidism increases systolic blood pressure predominantly due to a decrease in the total peripheral resistance and increase in cardiac output. Hyperthyroidism increases androgen conversion to estrogen through enhanced aromatization, resulting in gynecomastia. 1 Decreased free‐testosterone levels are present in thyrotoxicosis due to increased SHBG. 4

Gynecomastia occurring with renal failure is not a new concept. 5 , 6 A decline in androgen levels shifts estrogen/androgen ratio in favor of estrogen. 7 A recent study of 78 men on chronic hemodialysis reported elevated levels of follicle‐stimulating hormone, leuteinizing hormone, prolactin, and parathyroid hormones and low testosterone levels. 8 In this study, 18% of the patients had gynecomastia.

There are several case reports of adrenal hyperplasia, adenoma, or cancer associated with Cushing's syndrome, gynecomastia, and hypertension. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 Often, estrogen levels are increased through the peripheral aromatization of the increased secretion of adrenal androgens or excessive estrogen production. Chronic, excess alcohol use, amphetamines, cyclosporine, and anabolic steroids are associated with an increase in blood pressure and gynecomastia. 1 , 14 Anabolic steroid use is recognized as a drug associated with hypertension. An interview of 97 young men who used anabolic steroids reported a high prevalence of gynecomastia (52%), hypertension (36%), and testicular atrophy (56%). 15

GYNECOMASTIA AND ANTIHYPERTENSIVE DRUGS

Amlodipine, 16 , 17 captopril, 18 clonidine, diltiazem, 19 , 20 doxazosin, enalapril, felodipine, 21 methyldopa, nifedipine, 19 , 21 prazosin, reserpine, spironolactone, 22 and verapamil 19 , 21 have been reported to cause gynecomastia. 1 , 2 , 3 Many of the incriminated drug cases are based on case reports of temporal association without a re‐challenge of the suspected drug after resolution of gynecomastia or consideration of concomitant disease or drugs. 2

The mechanism of gynecomastia with calcium antagonists is unclear. 19 Verapamil has been reported to increase prolactin levels, but this was not elevated in one case with diltiazem. 20 , 21 Captopril‐reported gynecomastia was not associated with alteration in prolactin or steroid hormone levels. 18

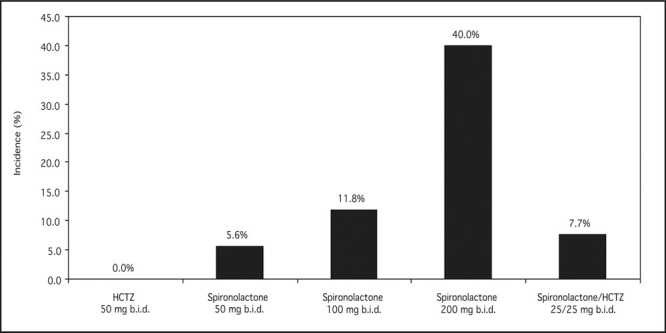

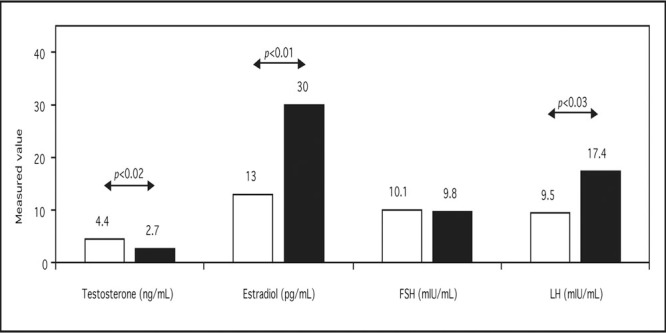

Gynecomastia is a well known side effect of spironolactone. The Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program reported a 1.2% prevalence of gynecomastia among 164 hospitalized patients (20.8%) experiencing adverse events (out of 788) treated with spironolactone. 22 In a prospective, double‐blind study, 79 men with essential hypertension were treated with one of five regimens for 12 weeks after a 4‐week placebo washout period (Figure). 23 Systolic blood pressure reduction was equally effective with the high dose of spironolactone compared with the combination of spironolactone and hydrochlorothiazide; however, gynecomastia was more common with spironolactone monotherapy. A French study of 182 patients reported an incidence of gynecomastia of 7.0%, 16.7%, and 52.2% of spironolactone dosed at 25–50 mg, 75–100 mg, and 150–300 mg daily, respectively. 24 , 25 Spironolactone‐induced gynecomastia is related to displacement of androgen from the androgen receptor, from SHBG, and increased metabolic clearance of testosterone and higher estradiol production, 26 possibly through enhanced aromatization. The net effect on circulating hormones is shown in Figure.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of gynecomastia in double‐blind study of 79 adult men. HCTZ=hydrochlorothiazide. Derived with permission from J Med. 1977;8:367‐377. 23

Figure 2.

Mechanism of spironolactone‐induced gynecomastia. FSH=follicle‐stimulating hormone; LH=leuteinizing hormone. Derived with permission from Ann Intern Med. 1977;87:398‐403. 26

CONCLUSIONS

For the hypertension specialist, nonphysiologic breast enlargement in men provides a clue to a secondary cause of hypertension or to an adverse antihypertensive drug reaction. Treatment is directed at the underlying cause of gynecomastia.

References

- 1. Braunstein GD. Gynecomastia. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:490–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thompson DF, Carter JR. Drug‐induced gynecomastia. Pharmacotherapy. 1993;13:37–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mosenkis A, Townsend RR. Gynecomastia and antihypertensive therapy. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2004; 6:469–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carlson HE. Gynecomastia. In: Morley JE, Korenman SG, eds. Endocrinology and Metabolism in the Elderly. Boston , MA : Blackwell Scientific Publications Inc.; 1992:294–307. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lindsay RM, Briggs JD, Luke RG, et al. Gynaecomastia in chronic renal failure. BMJ. 1967; 4:779–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schmitt GW, Shehadeh I, Sawin CT. Transient gynecomastia in chronic renal failure during chronic intermittent hemodialysis. Ann Intern Med. 1968;69:73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baumann G, Reza P, Chatterton R, et al. Plasma estrogens, androgens, and von Willebrand factor in men on chronic hemodialysis. Int J Artif Organs. 1988;11:449–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zamd M, Farh M, Hbid O, et al. Sexual dysfunction among 78 Moroccan male hemodialysis patients: clinical and endocrine study [in French]. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2004;65:194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Malchoff CD, Rosa J, DeBold CR, et al. Adrenocorticotropinindependent bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia: an unusual cause of Cushing's syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1989;68:855–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ghazi AA, Mofid D, Rahimi F, et al. Oestrogen and cortisol producing adrenal tumour. Arch Dis Child. 1994;71:358–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Paja M, Diez S, Lucas T, et al. Dexamethasone‐suppressible feminizing adrenal adenoma. Postgrad Med J. 1994;70:584–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rapetti S, Francia G, Iacono C, et al. An unusual case of Cushing's syndrome due to ACTH‐independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia. Chir Ital. 2003;55:235–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zayed A, Stock JL, Liepman MK, et al. Feminization as a result of both peripheral conversion of androgens and direct estrogen production from an adrenocortical carcinoma. J Endocrinol Invest. 1994;17:275–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Korkia P, Stimson GV. Indications of prevalence, practice and effects of anabolic steroid use in Great Britain. Int J Sports Med. 1997;18:557–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cornes PG, Hole AC. Amlodipine gynaecomastia. Breast. 2001;10:544–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zochling J, Large G, Fassett R. Gynaecomastia and amlodipine. Med J Aust. 1994;160:807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Markusse HM, Meyboom RH. Gynaecomastia associated with captopril. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1988;296:1262–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tanner LA, Bosco LA. Gynecomastia associated with calcium channel blocker therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:379–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Otto C, Richter WO. Unilateral gynecomastia induced by treatment with diltiazem. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boyd IW. Adverse Drug Reactions Advisory Committee. Gynaecomastia in association with calcium antagonists. Med J Aust. 1994;161:328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Greenblatt DJ, Koch‐Weser J. Adverse reactions to spironolactone. A report from the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program. JAMA. 1973;225:40–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nash DT. Antihypertensive effect and serum potassium homeostasis: comparison of hydrochlorothiazide and spironolactone alone and in combination. J Med. 1977;8:367–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jeunemaitre X, Chatellier G, Kreft‐Jais C, et al. Efficacy and tolerance of spironolactone in essential hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 1987;60:820–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jeunemaitre X, Kreft‐Jais C, Chatellier G, et al. Long‐term experience of spironolactone in essential hypertension. Kidney Int Suppl. 1988;26:S14–S17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rose LI, Underwood RH, Newmark SR, et al. Pathophysiology of spironolactone‐induced gynecomastia. Ann Intern Med. 1977;87:398–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]