Abstract

The prevalence of heart failure is increasing in modern societies. Hypertension is a major contributor to the development of heart failure, whether through the development of left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction or by promoting atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction, which eventually leads to systolic dysfunction and left ventricular dysfunction. Effective therapy for hypertension can prevent more than 50% of heart failure events. Most studies done in the last three decades have used β blockers with diuretics as the modality of therapy. These agents have been shown to effectively prevent the development of heart failure. More recent comparative studies have shown that use of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers are also effective in preventing heart failure. Calcium channel blockers, however, seem to be less effective in preventing development of heart failure in patients with hypertension. It needs to be emphasized that the most important variable in preventing heart failure is the appropriate treatment of hypertension.

Heart failure (HF) is a dominant illness in developed societies and the most common cause of hospital admissions for patients over the age of 65 years. It is also the single most important consumer of health care dollars. The prevalence of HF increases with age, and as the population ages the prevalence of HF increases exponentially. HF can be caused by systolic or diastolic dysfunction of the left ventricle, but commonly the two coexist.

Hypertension is the most common cause of HF, and most patients who have developed HF have a history of hypertension. In a study by Perera, 1 before the availability of effective antihypertensive drug therapy, out of 500 patients with uncontrolled hypertension followed for over 20 years, 50% died of HF (Figure 1). Data from the Framingham Heart Study 2 indicate that even mild forms of hypertension over a long period of time (16‐year follow‐up) double the risk of HF. The risk is greater in individuals over the age of 60 years; HF is more common in men than in women.

Figure 1.

Cardiovascular complications of untreated hypertensions (N=500). Enceph=encephalopathy; MI=myocardial infarction; CHF=congestive heart failure. Adapted from J Chron Dis. 1955;1:33–42. 1

Hypertension can lead to HF by one of two pathways: Either by causing left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and diastolic dysfunction that can lead to HF, or by promoting and speeding up the process of atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction (MI), with resultant ischemic heart disease and HF (Figure 2). 3 In clinical terms, diastolic dysfunction is presumed present in patients with symptoms and findings consistent with HF, but with a normal ejection fraction (>45–50). It is associated with stiffness of the myocardium, increased filling pressures with delayed diastolic filling, and pulmonary congestion. Systolic dysfunction is associated with myocardial damage, either global or regional, usually secondary to MI. An echocardiogram is usually required to distinguish between systolic and diastolic dysfunction, although the two forms commonly coexist.

Figure 2.

Progression from hypertension to heart failure. LVH=left ventricular hypertrophy; MI=myocardial infarction; CHF=congestive heart failure; LV=left ventricular; HF=heart failure. Adapted from Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1789–1796. 3

LVH has been clearly identified as an independent predictor of cardiovascular (CV) disease and HF. Although it is most commonly associated with diastolic dysfunction, it is also associated with increased risk for MI and eventually HF through reduced contractility and a decreased ejection fraction.

Numerous studies have shown that drug therapy of hypertension results in regression of left ventricular (LV) mass and improvement in surrogate end points of LV function. Several recent studies have also demonstrated a reduction of risk from CV complications as a result of LVH regression. Koren and coworkers 4 have shown that patients who demonstrate LVH regression over a 10‐year period have much better prognosis than patients who continue to have LVH or demonstrate increase in LV mass. Similarly, Vendecchia et al. 5 showed that patients who normalize or maintain normal LV mass over a 3‐year period had a much lower incidence of CV events than those who increased their LV mass.

The most important study that addressed patients with LVH and reduction of CV complications, including HF, was the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction (LIFE) in Hypertension study. 6 This trial is important because it was randomized, prospective, double‐blind, and included a population large enough to power the study to demonstrate differences between study groups. LIFE included 9193 patients with hypertension and ECG LVH. Patients were randomized to a losartan‐based or atenolol‐based treatment regimen. The objective was to reduce blood pressure (BP) to the same level to assess specific drug effects on prevention of CV complications. Approximately 10% of the patients in the LIFE study participated in the echocardiographic substudy. 7 , 8 These patients had echocardiograms at baseline and at yearly intervals thereafter. The echocardiographic substudy provided information on changes in LV mass and functional parameters of the left ventricle.

After approximately 4.5 years of follow‐up, results from the main LIFE study indicated that patients treated with losartan‐based therapy had 25% fewer strokes than patients treated with the atenolol regimen. 9 This effect was present despite the fact that both therapies reduced BP to the same level. Total mortality, MIs, hospitalizations for HF, and need for revascularization were similar between the two groups (with similar BP outcome), indicating a similar degree of protection for these complications.

The echocardiographic substudy demonstrated that LV mass was reduced substantially with most of the effect realized in the first year of therapy, and with a lesser effect thereafter. 7 , 8 Patients who demonstrated regression of LVH compared with those who maintained increased LV mass had a 66% lower CV mortality, 52% fewer MIs, and 22% fewer strokes. LV mass was reduced significantly with both atenolol‐and losartan‐based strategies, but the reduction was greater with losartan. At every data point, the reduction of LV mass was greater with the angiotensin receptor blocker compared with the β blocker. This finding is consistent with data from other smaller studies. 10

In a meta‐analysis of 75 well‐designed small studies, Klingbiel and colleagues, 11 reported that LV mass was reduced more effectively with ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers, than with other medical therapies. However, most antihypertensive therapies will result in a reduction of LV mass, except for the direct vasodilators. It is important to state that there are no data indicating that angiotensin receptor blocker therapy prevents HF through improvement of diastolic dysfunction or regression of LVH.

The second pathway that leads to HF is through atherosclerosis, MI, and systolic dysfunction. Numerous studies have shown that hypertension is a strong risk factor for the development of coronary disease. Recently, a large meta‐regression analysis of close to one million patients showed a close‐graded and continuous relation of systolic and diastolic BP with the risk for MI and stroke. 12 This relationship was present for all ages and existed from pressures as low as 115 mm Hg systolic or 70 mm Hg diastolic. 12 Furthermore, several studies have shown that treatment of hypertension can substantially reduce that risk and prevent more than 50% of HF events.

In a meta‐analysis by Moser and Hebert, 13 of 13,837 patients included in clinical trials, it was noted that drug therapy mostly β blockers/diuretics can reduce the risk of HF by 55%, compared with placebo. In this analysis, the placebo‐treated patients had 240 cases of HF and the actively treated patients experienced only 112 cases of HF.

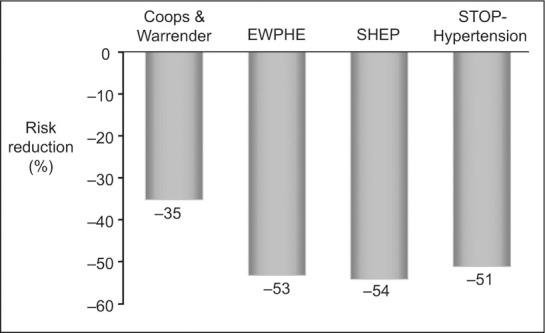

Since the prevalence of HF is much higher in the elderly, prevention is paramount. In four studies of older patients, antihypertensive drug therapy consistently prevented HF by ≈50% (Figure 4). 2 The Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) study 14 is the largest and best known of these trials and included elderly patients with isolated systolic hypertension (Figure 5). In this study, overall HF was reduced by 50% with the use of diuretics and β blockers, when needed, compared with placebo. In patients with coronary disease or post‐MI, the occurrence of HF was reduced by 80%.

Figure 4.

Risk reduction of heart failure in elderly hypertensives. EWPHE=European Working Party on High Blood Pressure; SHEP=Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program; STOP=Swedish Trial in Old Patients With Hypertension. Adapted from JAMA. 1996;275:1557–1562. 2

Figure 5.

Fatal and nonfatal hospitalized heart failure. Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program study by age group. Adapted from JAMA. 1997;278:212–216. 14

There is no doubt that treatment of hypertension can prevent more than half of HF events. The question that has been debated over the last decade or so is whether newer agents such as the angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or calcium channel blockers are more effective than the older ones, diuretics and β blockers. 13 Several studies have addressed this question with varying results.

The Controlled Onset Verapamil Investigation of Cardiovascular End Points (CONVINCE) study 15 compared verapamil to standard therapy (diuretics or β blocker therapies) in over 16,000 patients. Overall, there was no difference between verapamil and standard therapy for most CV end points, but there were 23% more HF events with verapamil compared with diuretics/β blockers.

The Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) 16 addressed the same question using a representative agent from each class of antihypertensive medications: amlodipine (calcium channel blocker), chlorthalidone (diuretic), doxazosin (α blocker) and lisinopril (angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor). The primary outcome in ALLHAT was fatal MI or coronary death. The primary end point was not significantly different among the groups, but there was a great difference in the prevention of HF. Compared with chlorthalidone, HF events were 104% higher with doxazosin, 38% higher with amlodipine, and 20% higher with lisinopril. A recent meta‐analysis of all published trials confirmed the above observations. These indicated that HF is prevented best with diuretics and β blockers, and not as well with calcium antagonists. 17

In summary, hypertension can lead to HF, effective therapy can prevent it, and diuretics seem to be as good as any of the other agents in preventing HF, as long as they normalize BP. Calcium channel blockers seem not to be as effective in preventing HF as angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors. Blockers of the renin‐angiotensin system seem to be as effective as diuretics/β blockers. It is important to treat BP to goal. Most of the benefit is obtained when a systolic pressure <140 mm Hg and a diastolic <90 mm Hg are reached, although special populations may benefit from lower BPs.

References

- 1. Perera GA. Hypertensive vascular dsease: description and natural history. J Chron Dis. 1955;1:33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Levy D, Larson MG, Vasan RS, et al. The progression from hypertension to congestive heart failure. JAMA. 1996;275:1557–1562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vasan RS, Levy D. The role of hypertension in the pathogenesis of heart failure. A clinical mechanistic overview. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1789–1796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Koren MJ, Ulin RJ, Koren AT, et al. Left ventricular mass change during treatment and outcome in patients with essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15:1021–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Verdecchia P, Schillaci G, Borgioni C, et al. Prognostic significance of serial changes in left ventricular mass in essential hypertension. Circulation. 1998;97:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dahlof B, Devereux RB, de Faire U, et al. The Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction (LIFE) in Hypertension study: rationale, design, and methods. The LIFE Study Group. Am J Hypertens. 1997;7:705–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Devereux RB, Palmieri V, Liu JE, et al. Progressive hypertrophy regression with sustained pressure reduction in hypertension: the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint Reduction study. J Hypertens. 2002;20:1445–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Devereux RB, Dahlof B, Gerdts E, et al. Regression of hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy by losartan vs. atenolol: the LIFE Trial. Circulation. 2004. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dahlof B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet. 2002;359:995–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schulman SP, Weiss JL, Becker LC, et al. The effects of antihypertensive therapy on left ventricular mass in elderly patients. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1350–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Klingbeil AU, Schneider M, Martus P, et al. A meta‐analysis of the effects of treatment on left ventricular mass in essential hypertension Am J Med. 2003;115:41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, et al. Age‐specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta‐analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903–1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moser M, Hebert PR. Prevention of disease progression, left ventricular hypertrophy and congestive heart failure in hypertension treatment trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:1214–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kostis JB, Davis BR, Cutler J, et al. Prevention of heart failure by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. SHEP Cooperative Research Group. JAMA. 1997;278:212–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Black HR, Elliott WJ, Grandits G, et al. Principal results of the Controlled Onset Verapamil Investigation of Cardiovascular End Points (CONVINCE) trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2073–2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Major cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients randomized to doxazosin vs. chlorthalidone: the antihypertensive and lipid‐lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial (ALLHAT). ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group . JAMA. 2000;283:1967–1975. Erratum in: JAMA. 2002;288:2976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Turnbull F. Effects of different blood‐pressure‐lowering regimens on major cardiovascular events: results of prospectively‐designed overviews of randomised trials. Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists' Collaboration. Lancet. 2003;362:1527–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]