Abstract

The prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States are analyzed using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database covering the period 1988–2002. Mean body mass index was 26.1±0.1 kg/m2 in 1988–1991 and 27.9±0.2 kg/m2 in 2001–2002 (p<0.001). In the same period, the prevalence of diabetes mellitus increased from 5.0% to 6.5% (p=0.03). Diastolic blood pressure was 73.3±0.2 mm Hg in 1988–1991 and 71.6±0.4 mm Hg in 2001–2002 (p<0.001). Among the 18–39 years and 60 years and older age groups, the prevalence of hypertension increased significantly since 1988–1991. Multiple regression shows age, body mass index, and being non‐Hispanic black were significantly associated with hypertension. In the period 1988–2002, the percentage receiving treatment and the percentage with blood pressure controlled increased significantly. In 2001–2002, significantly more people with hypertension and diabetes reached a blood pressure target of <130/85 mm Hg. Overall, the control rates were low, especially among middle‐aged Mexican‐American men (8%).

Almost one in three adults has hypertension in the United States. 1 Hypertension, a major risk factor for myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, and renal failure, affects at least 65 million adult Americans. 1 Treatment of hypertension is remarkably effective; a small reduction in blood pressure (BP) results in a large reduction in the risk of stroke and myocardial infarction. 2 Given the high prevalence of hypertension in the community, the detection of hypertension and its control and long‐term follow‐up are very important. In that regard, there is tremendous room for improvement. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 3 , 4 , 5 have shown in successive studies that the hypertension control rates have improved very little over decades. In 1999–2000, 68.9% of the NHANES participants who were hypertensive were aware of their hypertension, and 58.4% received treatment, but only 31% had good BP control. 5 Data from the NHANES study conducted in 2001–2002 have recently become available. 6 Here, we report the latest trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control in the United States.

METHODS

NHANES 6 is a large health and nutritional survey of the civilian noninstitutionalized population of the United States. Its methodology has been described in previous publications and also on its Web site. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 Since 1999, it has become a continuous survey program. The 2001–2002 NHANES results are available online. 10 All participants gave informed consent and the study received approval from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Institutional Review Board.

Data extracted from the database included age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), BP, and history of hypertension and diabetes mellitus. BP was measured manually by a trained operator according to a standard protocol. In 2001–2002, a small proportion of participants (n=401) were interviewed but not examined. They were not included in the analysis.

Hypertension was defined as an average systolic BP (SBP) of ≥140 mm Hg or an average diastolic BP (DBP) of ≥90 mm Hg, or if the participant was already taking antihypertensive medications. The same BP criteria were used for diabetic participants. Participants were asked “Have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you had hypertension, also called high blood pressure?” A positive answer was taken to mean that they were aware of their hypertension. Participants were considered to be treated if they answered “yes” to the question “Because of your high BP/hypertension, are you now taking prescribed medicine?” Hypertension was considered to be controlled in those taking medications if the average SBP was <140 mm Hg and the average DBP was <90 mm Hg. Participants were considered diabetic if previously diagnosed by a doctor or if they were using insulin or oral antidiabetes medications. For people with diabetes, hypertension was considered to be controlled if the average SBP was <130 mm Hg and the average DBP was <85 mm Hg.

Data were analyzed using SAS (version 8, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) or, after conversion of files, SPSS (SPSS for Windows, version 11.5, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). In NHANES, African Americans, Mexican Americans, and people aged 60 years or older were oversampled to provide better estimates of these groups. To adjust for oversampling and nonresponse bias, sampling weights were used in the calculation of means and in regression analysis. 11 For analyzing differences over time, the 2001–2002 data were compared with the 1988–1989 data and the 1999–2000 data using the t test. A conservative approach was adopted for statistical significance (α=0.01) to help account for multiple comparisons. Estimates with a coefficient of variation >0.3 or a sample size smaller than the recommended size for the design effect or the estimated proportion were considered unreliable. Multiple regression analysis was performed with hypertension as the dependent variable, and age, sex, race/ethnicity, and BMI as predictor variables.

RESULTS

Table I shows the number of participants in the four phases of NHANES (1988–1991,1991–1994, 1999–2000,2001–2002) by sex, race/ethnicity, and age group. The numbers of black and Mexican‐American participants and participants aged 60 years and over reflect the effect of oversampling of these groups in the study design.

Table I.

Number of Participants by Sex, Race/Ethnicity, and Age in Four NHANES Phases

| 1988–1991 (n=9901) | 1991–1994 (n=9717) | 1999–2000 (n=5448) | 2001–2002 (n=5993) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity, Age (yr) | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women |

| Total | 4781 | 4812 | 4083 | 5187 | 2337 | 2618 | 2653 | 2905 |

| Non‐Hispanic white | 2244 | 2260 | 1585 | 2283 | 1131 | 1222 | 1441 | 1613 |

| 18–39 | 628 | 656 | 417 | 670 | 368 | 465 | 448 | 600 |

| 40–59 | 564 | 513 | 382 | 562 | 289 | 278 | 434 | 405 |

| ≥60 | 1052 | 1091 | 783 | 1051 | 474 | 479 | 559 | 608 |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 1190 | 1270 | 1246 | 1632 | 485 | 564 | 575 | 628 |

| 18–39 | 558 | 601 | 635 | 870 | 205 | 247 | 255 | 293 |

| 40–59 | 323 | 318 | 322 | 458 | 138 | 151 | 171 | 169 |

| ≥60 | 309 | 358 | 289 | 304 | 142 | 166 | 149 | 166 |

| Mexican American | 1347 | 1282 | 1252 | 1272 | 721 | 832 | 637 | 664 |

| 18–39 | 733 | 686 | 664 | 703 | 329 | 407 | 335 | 361 |

| 40–59 | 302 | 311 | 291 | 285 | 168 | 203 | 165 | 149 |

| ≥60 | 312 | 285 | 297 | 284 | 224 | 222 | 137 | 154 |

| NHANES=National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey | ||||||||

Table II shows the age, race/ethnicity, BMI, BP, and diabetic status of the US population estimated from NHANES. Since 1988–1991, there was a trend toward fewer participants missing a physical examination, so that in 2001–2002, only 6.7% did not have an examination. The mean BMI was 26.1±0.1 kg/m2 in 1988–1991 and 27.9±0.2 kg/m2 in 2001–2002 (p<0.001). In the same period, the prevalence of diabetes mellitus increased from 5.0% to 6.5% (p=0.03). The DBP, however, was 73.3±0.2 mm Hg in 1988–1991 but 71.6±0.4 mm Hg in 2001–2002 (p<0.001).

Table II.

Characteristics of Participants in Four NHANES Phases*

| Characteristics | 1988–1991(n=9901) | 1991–1994 (n=9717) | 1999–2000 (n=5448) | 2001–2002 (n=5993) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interviewed but not examined (n [%]) | 1076 (11) | 790 (8) | 472 (9) | 401 (6.7) |

| Age (mean [SE]) (yr) | 43.4 (0.4) | 44.1 (0.6) | 44.0 (0.3) | 44.4 (0.5) |

| Age group (%) (yr) | ||||

| 18–39 | 40 | 43 | 42 | 42.0 |

| 40–59 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 27 |

| ≥60 | 35 | 32 | 34 | 31 |

| Women (%) | 52 | 52 | 52 | 52 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | ||||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 77 | 75 | 70 | 71.5 |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11.2 |

| Mexican American | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7.3 |

| Other | 7 | 9 | 12 | 9.9 |

| Body mass index (mean [SE]) (kg/m2) | 26.1 (0.1)** | 26.7 (0.1) | 27.8 (0.1) | 27.9 (0.2)** |

| Never had BP checked (%) | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| BP (mean [SE]) (mm Hg) | ||||

| Systolic | 122.0 (0.5) | 122.1 (0.4) | 122.9 (0.4) | 122.0 (0.5) |

| Diastolic | 73.3 (0.2)** | 74.4 (0.3) | 72.1 (0.2) | 71.6 (0.4)** |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 5 | 5 | 7 | 6.5 |

| NHANES=National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; SE=standard error; *data are weighted to the US population; **p<0.05 for differences between 1988–1991 and 2001–2002 | ||||

Table III shows the prevalence of hypertension in the United States, estimated from the NHANES databases. Among the 18–39 years and 60 years and older age groups, the prevalence of hypertension increased significantly, from 5.1% and 57.9%, respectively, in 1988–1991, to 7.1% and 66.0%, respectively, in 2001–2002.

Table III.

Prevalence of Hypertension by Age Group in the US Population, 1988–2002*

| Prevalence (% [SE]) | Change, 1988–2002 | Change, 1999–2002 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 1988–1991 | 1991–1994 | 1999–2000 | 2001–2002 | (% [95% CI]) | p | (% [95% CI]) | p |

| 18–39 | 5.1 (0.6) | 6.1 (0.6) | 7.2 (1.1) | 7.1 (0.5) | 2.0 (0.5–3.5) | 0.01 | −0.1 (−2.5 to 2.3) | 0.93 |

| 40–59 | 27.0 (1.4) | 24.3 (2.2) | 30.1 (1.8) | 28.1 (1.9) | 1.1 (−3.5 to 5.7) | 0.64 | −2.0 (−7.1 to 3.1) | 0.44 |

| ≥60 | 57.9 (2.0) | 60.1 (1.1) | 65.4 (1.6) | 66.0 (1.5) | 8.1 (3.2–13.0) | 0.001 | 0.6 (−3.7 to 4.9) | 0.78 |

| SE=standard error; CI=confidence interval; *data are weighted to the US population | ||||||||

Table IV shows the results of multiple regression with hypertension as the dependent variable. Age, BMI, and being non‐Hispanic black were significantly associated with hypertension, whereas sex was not.

Table IV.

Multiple Regression Analysis of the Association Between Hypertension Prevalence and Demographic Factors and Body Mass Index (BMI)

| Regression Coefficient (SE) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | 1998–1991 | 1991–1994 | 1999–2000 | 2001–2002 |

| Age (per 1‐yr increase) | 1.2 (0.04)* | 1.2 (0.03)* | 1.3 (0.04)* | 1.3 (0.03)* |

| Sex (referent: women) | 3.5 (1.3) | 0.03 (0.7) | 1.4 (1.5) | −1.8 (1.0) |

| Race/ethnicity (referent: Mexican American) | ||||

| Non‐Hispanic white | −1.1 (0.9) | −0.2 (1) | 0.6 (1.4) | 0.7 (1.1) |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 7.0 (1.4)* | 10 (0.1)* | 8.2 (1.7)* | 13.3 (1.4)* |

| BMI (per kg/m2 of increase) | 1.3 (0.07)* | 1.3 (0.1)* | 1.2 (0.1)* | 0.9 (0.1)* |

| R 2 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.28 |

| SE=standard error; *p<0.001 for the independent association between hypertension prevalence and each factor after adjusting for the remaining factors | ||||

Table V shows the rate of awareness, treatment, and BP control in the United States, estimated from the NHANES databases. In the period 1988–2002, the awareness of hypertension has not changed significantly, but the percentage receiving treatment and the percentage with BP controlled had increased significantly, from 52.4% to 61.2%, and from 24.6% to 34.3%, respectively. There were no substantial changes in the awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension between the periods 1999–2000 and 2001–2002, except that significantly more people with both hypertension and diabetes reached the BP target of <130/85 mm Hg (28.5% to 35.9%).

Table V.

Awareness, Treatment, and Control Among Participants With Hypertension in the US Population, 1988–2002*

| Prevalence (% [SE]) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1988–1991 | 1991–1994 | 1999–2000 | 2001–2002 | Change, 1988–2002 | Change, 1999–2002 | |||

| (n=3045) | (n=3017) | (n=1565) | (n=1696) | (% [95% CI]) | p | (% [95% CI]) | p | |

| Awareness | 69.2 (1.3) | 67.8 (1.8) | 68.9 (1.5) | 71.2 (1.5) | 2.0 (−1.9 to 5.9) | 0.31 | 2.3 (−1.9 to 6.5) | 0.28 |

| Treatment | 52.4 (1.4) | 52.0 (1.0) | 58.4 (2.0) | 61.2 (1.5) | 8.8 (4.8–12.8) | <0.001 | 2.8 (−2.1 to 7.7) | 0.26 |

| Control | ||||||||

| All treated | 46.9 (2.2) | 43.6 (1.7) | 53.1 (2.4) | 56.1 (1.2) | 9.2 (4.3–14.1) | <0.001 | 3.0 (−2.3 to 8.3) | 0.26 |

| All with hypertension | 24.6 (1.4) | 22.7 (1.1) | 31.0 (2.0) | 34.3 (1.4) | 9.7 (5.8–13.6) | <0.001 | 3.3 (−1.5 to 8.1) | 0.18 |

| Hypertensive diabetics treated to <140/90 mm Hg | 53.1 (4.5) | 41.6 (5.8)** | 46.9 (4.7) | 56.5 (3.2) | 3.4 (−7.4 to 14.2) | 0.54 | 9.6 (−1.5 to 20.7) | 0.09 |

| Hypertensive diabetics treated to <130/85 mm Hg | 28.5 (4.2) | 17.2 (4.2)** | 25.4 (4.0) | 35.9 (3.3) | 7.4 (−3.1 to 17.9) | 0.17 | 10.5 (0.3–20.7) | 0.04 |

| SE=standard error; CI=confidence interval; *data are weighted to the US population; **estimates are unreliable because of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey minimum sample size criteria or coefficient of variation of at least 0.30 | ||||||||

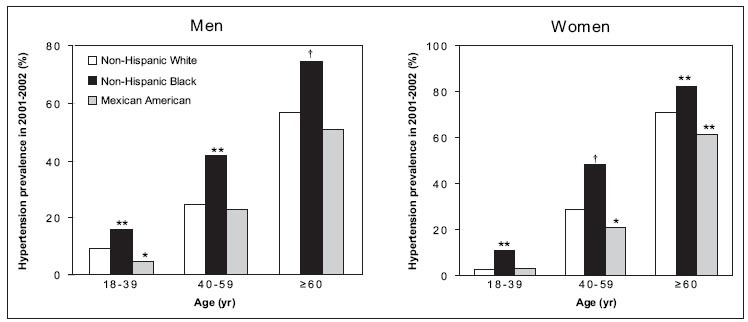

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of hypertension in non‐Hispanic whites, non‐Hispanic blacks, and Mexican Americans in the 18–39 years, 40–59 years, and 60 years and older age groups. It shows the marked increase in the prevalence of hypertension with age, and the significantly higher prevalence of hypertension in non‐Hispanic blacks. In the 60 years and older age group, hypertension is present in 75% of non‐Hispanic black men and 82% of non‐Hispanic black women, compared with 57% and 71% of non‐Hispanic white men and women, and 51% and 61% of Mexican‐American men and women, respectively.

Figure 1.

Hypertension prevalence in 2001–2002 by age and race/ethnicity in men and women. Data are weighted to the US population; non‐Hispanic whites are the referent for race/ethnicity comparisons. *p<0.05 for the difference within the same age group; **p<0.01 for the difference within the same age group; †p<0.001 for the difference within the same age group

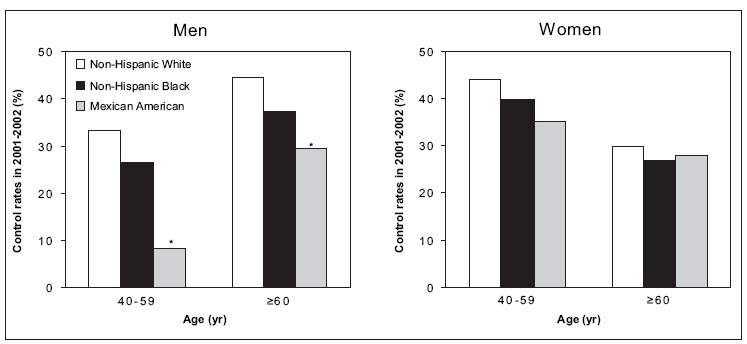

Figure 2 shows the rate of BP control in the different race/ethnic groups and age groups. Overall, the control rates were low, especially among middle‐aged Mexican‐American men (8%), whereas in non‐Hispanic white and non‐Hispanic black men, the rates were 33% and 27% respectively.

Figure 2.

Overall hypertension control rates in 2001–2002 by age and race/ethnicity in men and women. Data are weighted to the US population. *p<0.001 for the difference within the same age group (non‐Hispanic whites are the referent for race/ethnicity)

DISCUSSION

The prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the NHANES study population have been reported previously. 3 , 4 , 5 The present report confirms previous observations and extends previous conclusions. In the 2001–2002 database there is evidence of improvement in BP control, particularly in people with diabetes. This suggests that clinicians are putting into practice the recommendations of hypertension guidelines, 12 which are, in turn, influenced by recent clinical trial evidence showing the benefit of tight BP control, especially in people with diabetes. 13 The latest guidelines emphasize the prevention of hypertension in those with prehypertension and the importance of BP control in those with hypertension. 14 BP targets for people with diabetes, moreover, have been revised to 130/80 mm Hg. Hopefully, the trend toward lower BP and better control of BP will continue. Not only is good BP control of critical importance in people with diabetes, 15 but the Valsartan Antihypertensive Long‐term Use Evaluation (VALUE) trial and other trials have reported that small differences in BP translate into clinical events. 15 , 16

The oversampling of non‐Hispanic blacks, Mexican Americans, and people aged 60 years and older allows more accurate characterization of these subgroups. The NHANES database highlights the high prevalence of hypertension among black Americans; in all age groups and in either sex, the prevalence of hypertension in non‐Hispanic black Americans is higher than in non‐Hispanic whites and Mexican Americans. The control of hypertension among black Americans is also marginally lower. The explanation for poorer hypertension control is not fully known but may include genetic, cultural, and social factors, including insurance and access to care and medications. 17 Physician inertia or nonadherence to guidelines may also be an important factor. Guidelines on the management of hypertension in African Americans highlight their specific problems and offer practical guidance. 18

Mexican Americans have the lowest prevalence of hypertension among the three groups. BP control, however, tends to be inferior. Indeed, the rate of control was only 8% in middle‐aged Mexican‐American men. This particular problem of the Mexican‐American community 19 suggests that more work is needed to increase awareness of hypertension, access to a regular source of health care, and promotion of a healthy lifestyle, as well as more attention to appropriate use of antihypertensive agents. 20

The prevalence of hypertension in the elderly has been on the rise since 1988, 21 notwithstanding the change in definition of an elevated SBP from 160 mm Hg to 140 mm Hg. There are likely to be multiple reasons for the increase. The increase in obesity and treatment of hypertension to prevent premature death may be contributing factors.

There has also been a marked increase in the prevalence of hypertension in younger adults aged 18–39 years. This may be partly related to the increase in obesity. 22

In the decade between 1988 and 2000, the proportion of hypertensives receiving treatment and the rate of BP control have increased significantly. Encouragingly, the 2001–2002 data showed further improvements, although not reaching statistical significance except in people with diabetes. The rate of BP control is still low, although it is considerably higher in the US than in other industrialized countries. 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 Ways to improve this may involve the use of a combination of antihypertensive drugs with different mechanisms of action, the use of combination formulations and once‐daily medications to improve compliance, and switching agents to find the most efficacious and best‐tolerated regimen for the individual patient. 14 Diet and exercise would enhance the effects of antihypertensive treatment and BP control. 27 , 28 , 29

CONCLUSIONS

We found that in the period 1998–2002, BMI and the prevalence of diabetes mellitus have increased in the United States. The mean DBP, however, has decreased, and control of BP in people with hypertension and diabetes has improved. Hypertension is more common among non‐Hispanic blacks, but BP control in Mexican Americans remains low.

References

- 1. Fields LE, Burt VL, Cutler JA, et al. The burden of adult hypertension in the United States 1999 to 2000: a rising tide. Hypertension. 2004;44: 398–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Staessen JA, Wang JG, Thijs L. Cardiovascular prevention and blood pressure reduction: a quantitative overview updated until 1st March 2003. J Hypertens. 2003;21: 1055–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Burt VL, Cutler JA, Higgins M, et al. Trends in the prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the adult US population: data from the Health Examination Surveys, 1960–1991. Hypertension. 1995;26: 60–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burt VL, Whelton P, Roccella EJ, et al. Prevalence of hypertension in the US adult population: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey,. 1988–1991. Hypertension. 1995;25: 305–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States,. 1988–2000. JAMA. 2003;290: 199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Available at: http:www. cdc.govnchsnhanes.htm. Accessed June 24, 2005.

- 7. National Center for Health Statistic .. Plan and Operation of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1988–1994. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1994. Vital Health Stat 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Center for Health Statistic .. Sample Design: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1992. Vital Health Stat 2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Center for Health Statistic .. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2000 data files. Available at: http:www.cdc.govnchsaboutmajornhanesNHANES9900.htm. Accessed June 24, 2005.

- 10. >National Center for Health Statistics . The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). 2000–2001 data files. Available at: http:www.cdc.govnchsaboutmajornhanesNHANES01‐02.htm. Accessed June 24, 2005.

- 11. Berglund PA. Analysis of complex sample survey data using the SURVEYMEANS and SURVEYREG procedures and macro coding. In: SAS Institute, Inc. Proceedings of the Twenty‐Seventh Annual SAS Users Group International Conference.Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sixth report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure [published correction appears in Arch Intern Med. 1998;158: 573]. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2413–2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering and low‐dose aspirin in patients with hypertension. Lancet. 1998;351: 1755–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289: 2560–2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group . Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ. 1998;317: 703–713. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Julius S, Kjelsen SE, Weber M, et al., For the VALUE Trial Group. Outcomes in hypertensive patients at high cardiovascular risk treated with regimens based on valsartan or amlodipine: the VALUE randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363: 2022–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rehman SU, Hutchison FN, Hendrix K, et al. Ethnic differences in blood pressure control among men at Veterans Affairs clinics and other health care sites. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165: 1041–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Douglas JG, Bakris GL, Epstein M, et al. Management of high blood pressure in African Americans: consensus statement of the Hypertension in African Americans Working Group of the International Society on Hypertension in Blacks. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163: 525–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lorenzo C, Serrano‐Rios M, Martinez‐Larrad MT, et al. Prevalence of hypertension in Hispanic and non‐Hispanic white populations. Hypertension. 2002;39: 203–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. He J, Muntner P, Chen J, et al. Factors associated with hypertension control in the general population of the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162: 1051–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Barker WH, Mullooly JP, Linton KL. Trends in hypertension prevalence, treatment, and control in a well‐defined older population. Hypertension. 1998;31(1 pt 2):552–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA. 2002;288: 1723–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Berlowitz DR, Ash AS, Hickey EC, et al. Inadequate management of blood pressure in a hypertensive population. N Engl J Med. 1998;339: 1957–1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kotchen JM, Shakoor‐Abdullah B, Walker WE, et al. Hypertension control and access to medical care in the inner city. Am J Public Health. 1998;88: 1696–1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hyman DJ, Pavlik VN. Characteristics of patients with uncontrolled hypertension in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2001;345: 479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lloyd‐Jones DM, Evans JC, Larson MG, et al. Treatment and control of hypertension in the community. Hypertension. 2002;40: 640–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Whelton PK, Appel LJ, Espeland MA, et al. Sodium reduction and weight loss in the treatment of hypertension in older persons: a randomized controlled trial of nonpharmacologic interventions in the elderly (TONE). TONE Collaborative Research Group. JAMA. 1998;279: 839–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miller ER Jr, Erlinger TP, Young DR, et al. Results of the Diet, Exercise, and Weight Loss Intervention Trial (DEWIT). Hypertension. 2002;40: 612–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Appel LJ, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, et al. Writing Group of the PREMIER Collaborative Research Group. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA. 2003;289: 2083–2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]