A previously healthy 50‐year‐old Vietnamese female presented May 4, 2004 with vaginal bleeding and new‐onset hypertension. She was gravida 5, para 3 with her last menstrual period April 13, 2004. Vaginal bleeding and cramping had been occurring daily for 3 weeks. A May 4, 2004 blood pressure (BP) was 190/90 with a heart rate of 76; 2+/4 peripheral edema was noted and lower extremity reflexes were absent. There was no tremor or skin warmth. Her thyroid was not enlarged or tender. A May 4, 2004 uterine ultrasound revealed a 17‐week uterus having grown from 13 weeks since April 15, 2004, representing a 4‐week growth in a 2.5‐week span. Laboratory showed 2+/4 proteinuria, alanine aminotransferase 88 (normal 5‐35 U/L), alkaline phosphatase 177 (normal 42‐121 U/L), bilirubin 0.7, platelet count 178,000 and thyroid stimulating hormone was 0.1 (normal 0.35‐6.0 international U/mL) with free T 4 2.56 (normal 0.62‐1.76 ng/dL).

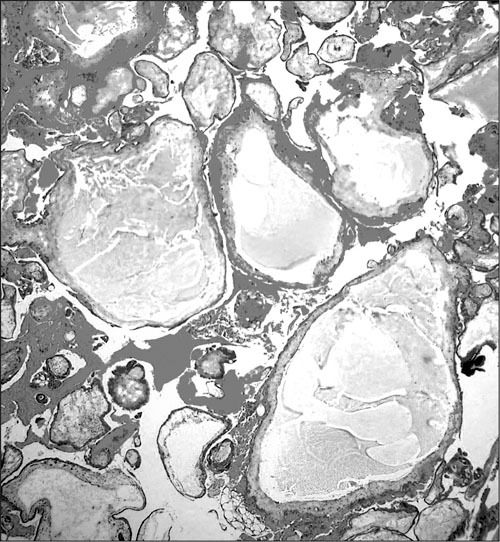

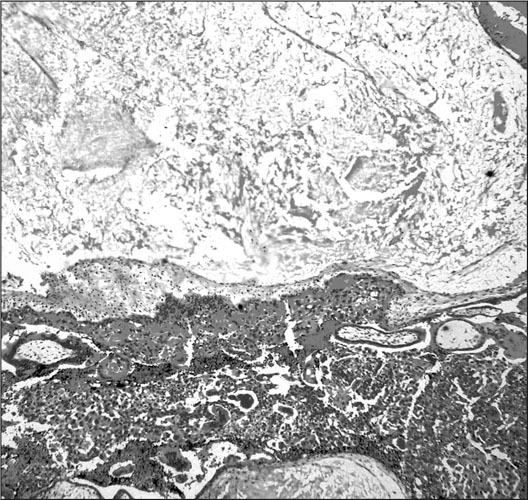

Propanolol 100 mg t.i.d. was started on May 4, 2004, before dilation and curettage that same day. Pathology demonstrated a complete hydatidiform mole with grape‐like chorionic villi distended with cistern formation in most of the villi, along with moderate trophoblastic proliferation (Figures 1, 2). An echocardiogram showed a minimal pericardial effusion with normal left ventricular size and function. She received a 24‐hour perioperative magnesium infusion with a 4‐g loading dose and a 2‐g/hour drip. BP, which had decreased to 130/60 mm Hg on IV magnesium, rose again to 174/84 mm Hg.

Figure 1.

Photomicrograph demonstrating placental tissue with markedly edematous chorionic villi involving cistern formation; hematoxylin and eosin staining

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph showing marked villous edema in a chorionic villus with cistern formation and subjacent trophoblastic proliferation; hematoxylin and eosin staining

The patient was discharged 2 days later; (May 6, 2004), on propylthiouracil 100 mg t.i.d., lisinopril 10 mg q.d., and clonidine 0.1 mg b.i.d.

On May 8, 2004 her physician‐husband brought her to the emergency department because of a BP of 200/95 mm Hg (no symptoms were present). Lisinopril was advanced to 10 mg b.i.d. and clonidine to 0.2 mg b.i.d., maintaining propylthiouracil at 100 mg t.i.d. On May 9, 2004, her husband brought her back to the emergency department because of elevated BPs. The patient did not have any complaints and specifically denied any pulmonary symptomatology. She appeared comfortable with BPs of 203/81,201/76, and 215/81, and a heart rate of 46. Her peripheral edema had spontaneously improved to 1+/4, and she still lacked lower extremity reflexes or tremor. Platelet count was 193,000 with normal hepatic transaminases. A β‐subunit human chorionic gonadotropin (β‐hCG) from May 4, 2004 of 448,300 mIU/mL (normal <5 mIU/mL) became known on May 9,2004. Abdominal, pelvic, chest, and brain computed tomography imaging were normal with the exception of 12 bilateral pulmonary modules, the largest measuring 1 cm in the right lower lobe consistent with metastatic disease, along with small bilateral pleural effusions. A total body thyroid scan showed no abnormal uptake but was performed following the iodinated contrast dye accompanying her computed tomography scan. Her antihypertensive medication was changed to hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg q.d., lisinopril 20 mg q.d., metoprolol 50 mg b.i.d., and nifedipine extended release 30 mg q.d., while continuing propylthiouracil 100 mg t.i.d.

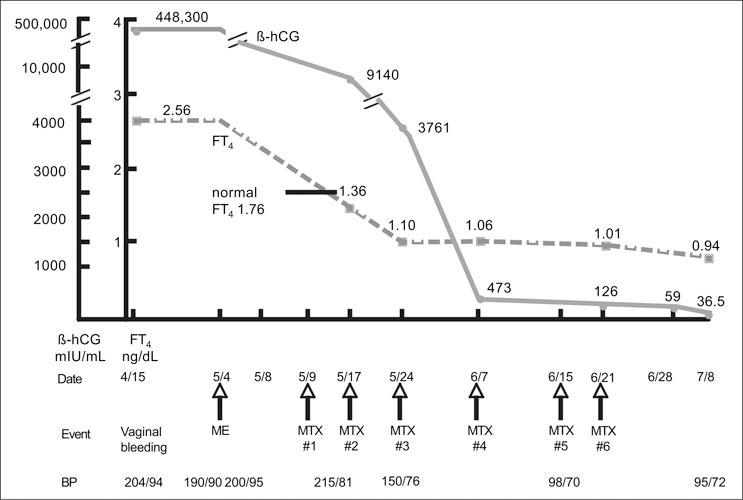

Methotrexate 50 mg IM weekly was initiated on May 9, 2004. BP on May 10, 2004 was 203/80 with a heart rate of 46. Figure 3 depicts the course of β‐hCG, FT4 and BP related to molar evacuation by dilatation and curettage followed by methotrexate administration. On clinic visit follow‐up June 15, 2004, following 6 weekly methotrexate dosages, her BP was 98/70. At that time, she was taking only hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg q.d. and metoprolol 50 mg b.i.d. Both of these medications were discontinued with maintenance of normotensive BP levels without treatment. Chest radiography revealed complete resolution of prior abnormalities.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of β‐hCG, FT4, related to date, events, and BP for case patient with metastatic trophoblastic disease. β‐hCG=β‐subunit human chorionic gonadotropin; FT4=free T4; ME=molar evacuation; BP=blood pressure; MTX=methotrexate

DISCUSSION

Hydatidiform moles are observed in approximately one in 600 therapeutic abortions and one in 1500 pregnancies in the United States. 1 Gestational trophoblastic disease includes complete and partial hydatidiform mole, choriocarcinoma, and placental‐site trophoblastic tumor; a spectrum of histologically distinct tumors of placental origin that share an exquisite sensitivity to chemotherapy and a high cure rate. These tumors are rare, making up <1% of all gynecological malignancies; they secrete β‐hCG as a tumor marker. 2 Vaginal bleeding is the most common presenting symptom, presenting in 93.8% (105/112) in one series of mole pregnancies, where hyperemesis gravidarum, expulsion of mole, and acute abdomen were rare alternative presentations. 2 , Table I exhibits the presenting signs and symptoms of complete molar pregnancy in a larger patient series where vaginal bleeding was a presenting symptom in 97%. 3 Vaginal bleeding and rapid increase in uterine dimension suggested a mole pregnancy in the patient under discussion. While excessive uterine enlargement relative to gestational age is one of the classic signs of complete mole, it is present in only half of these patients. 3 Clinical hyperthyroidism may accompany hydatidiform mole in about 7% of cases.

Table I.

Presenting Symptoms and Signs in Patients With Complete Molar Pregnancy*

| Sign | Complete Mole (%) (n=307) |

|---|---|

| Vaginal bleeding | 97 |

| Excessive uterine size | 51 |

| Prominent ovarian theca lutein cysts | 50 |

| Toxemia | 27 |

| Hyperemesis | 26 |

| Hyperthyroidism | 7 |

| Trophoblastic emboli | 2 |

| *Reproduced with permission from Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. In: Berek JA, Hacker JA, eds. Practical Gynecologic Oncology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Williams & Wilkins; 2000:617. | |

Complete and partial hydatidiform mole pregnancies are distinguished on the basis of gross morphology and histopathology. Identifiable embryonic or fetal tissues are lacking in complete moles and generalized hydatidiform swelling and diffuse trophoblastic hyperplasia are noted in the absence of embryonic or fetal tissue. 4 Cytogenetic studies demonstrate that the molar chromosomes in complete mole are entirely of paternal origin. 5 In contrast with complete moles, partial moles often contain fetal tissue.

Initial differential diagnosis for this patient included a moderate, but increasing, probability of hydatidiform mole pregnancy associated with preeclampsia and thyrotoxicosis. The extremely elevated β‐hCG led to the detection of asymptomatic pulmonary metastases following dilation and curettage and established a diagnosis of metastatic gestational trophoblastic disease associated with biochemical hyperthyroidism. The sole clinical manifestation of her hyperthyroid condition was hypertension.

Twenty‐five percent of women with complete hydatidiform mole present with hypertension, hyperreflexia, and proteinuria consistent with preeclampsia. 6 , 7 However, the wide pulse pressure and persistence of hypertension following dilatation and curettage seen in this patient would be quite unusual for preeclampsia. At least 24 hours of prophylactic magnesium infusion is recommended following uterine evacuation to prevent eclamptic seizures under these circumstances. 8 The patient received this therapy. She had proteinuria and edema, but despite hyperthyroidism and probable preeclampsia, had absent deep tendon reflexes. Fewer than10% of patients with complete mole have symptoms of tremor and tachycardia in association with a more severe elevation of thyroid hormone levels; a larger subset have lesser degrees of thyroid hormone elevation in the absence of any clinical symptomatology. 6 A possible explanation for the frequent discrepancy between biochemical and clinical thyroid disease may be due to the short duration of the biochemical abnormality. 9

Hydatidiform mole tissue may secrete glycosylated hCG molecules with enough thyroid stimulating hormone receptor crossover specificity to induce thyroid overactivity. 10 , 13 Both free T 4 and free T 3 may be expressed by the tumor in sufficient quantities to suppress thyroid stimulating hormone. 9 High levels of circulating hCG may be associated with goiter and clinical sequelae of hyperthyroidism. 14 Antitumor therapy and reduced hCG levels may then lead to resolution of biochemical disease and symptoms, 15 but not in all cases. 16 A separate chorionic thyrotropin has been postulated as an etiologic mechanism of thyrotoxicosis in mole pregnancy, but remains to be discovered. When thyrotoxicosis is a complication of mole pregnancy, periprocedure β‐blockade therapy is recommended to prevent thyroid storm complicating surgery and/or anesthesia. 8 This was administered to this patient in preparation for her uterine curettage. Thyroid storm manifestations may include hyperthermia, delirium, seizures, atrial fibrillation, and cardiovascular collapse.

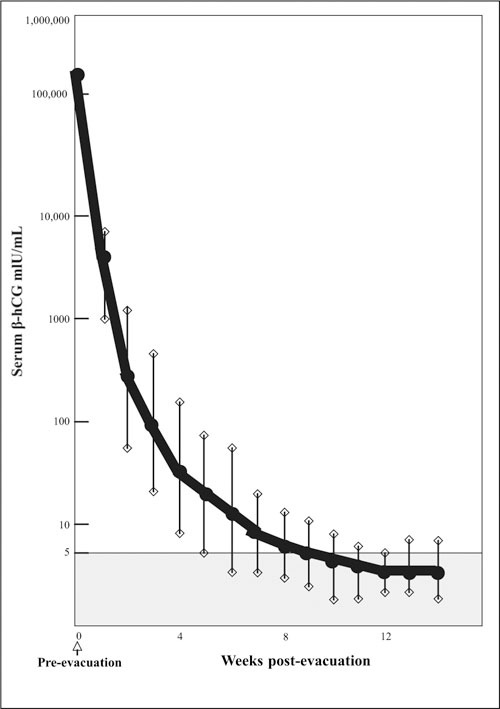

Following molar evacuation, the natural history for the majority of patients is normal involution, but 15% develop local uterine invasion and metastases develop in 4%. 17 Four percent of 858 patients had one of three signs of marked trophoblastic proliferation, any one of which increased the risk of metastasis more than 10‐fold, 8.8% vs. 0.6%. The three risk factors are: 1) hCG>100,000 mIU/mL; 2) excessive uterine enlargement; or 3) theca lutein cysts >6.0 cm. 17 The present case, therefore, was at a higher risk for metastatic disease with a β‐hCG level of 448,300 mIU/mL. Figure 4 illustrates the normal regression curve of β‐hCG following molar evacuation showing a rapid decrease. 18 A rapid return of previously elevated thyroid function tests to the normal range also occurs. 19

Figure 4.

Normal regression curve of β‐hCG after molar evacuation. Reproduced with permission from Morrow CP, Kletzky OA, Townsend DE, et al. Clinical and laboratory correlates of molar pregnancy and trophoblastic disease. In: Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1977;128:424‐430. 18

Once the severe β‐hCG elevation in the present case became known, a search for metastatic disease led to the discovery of multiple pulmonary metastases on the chest radiograph and chest computed tomography scanning. Of the 4% of metastatic cases which occur following uterine curettage of complete mole, 80% are pulmonary 14 and may be associated with chest pain, cough, hemoptysis, or present without any symptoms, as in this patient. The four principle radiographic patterns are: 1) an alveolar or “snowstorm” pattern; 2) discrete rounded densities; 3) pleural effusion and; 4) an embolic pattern caused by pulmonary arterial occlusion resulting in pulmonary hypertension. 15 The relative incidence of common metastatic sites is presented in Table II. 14 Symptoms at metastatic sites may be related to bleeding because these tumors are highly vascular. 15

Table II.

Relative Incidence of Common Metastatic Sites From Gestational Trophoblastic Disease (%)*

| Lungs | 80 |

| Vagina | 30 |

| Pelvis | 20 |

| Brain | 10 |

| Liver | 10 |

| Bowel, kidney, spleen | <5 |

| Other | <5 |

| Undetermined | <5 |

| *Reproduced with permission from Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. In: Berek JA, Hacker JA, eds. Practical Gynecologic Oncology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Williams & Wilkins; 2000:624. | |

As early as 1948, Hertz 20 showed that fetal tissues required large amounts of folic acid to support trophoblastic growth in experimental animals and that this growth could be inhibited by the folic acid antagonist, methotrexate. Investigators at the National Cancer Institute 21 demonstrated the efficacy of chemotherapy in the treatment of metastatic gestational trophoblastic disease in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Classification and treatment schemes have been developed and validated, distinguishing: 1) nonmetastatic; 2) metastatic low‐risk; and 3) metastatic high‐risk gestational trophoblastic disease. High‐risk metastatic disease is distinguished by liver and/or brain dissemination. The most commonly utilized anatomic staging system adopted by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), 22 and the World Health Organization (WHO) scoring system 23 are shown in Tables III and IV.

Table III.

Staging of Gestational Trophoblastic Neoplasia, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO)*

| Stage I | Confined to uterine corpus |

| Stage II | Metastases to pelvis and vagina |

| Stage III | Metastases to lung |

| Stage IV | Distant metastases |

| *Reproduced with permission from Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. In: Berek JA, Hacker JA, eds. Practical Gynecologic Oncology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Williams & Wilkins; 2000:625. | |

In the absence of brain or liver lesions, this patient with bilateral rounded pulmonary densities and pleural effusions fell in the low‐risk metastatic category and rapidly achieved complete remission with single‐agent methotrexate without a hysterectomy. At the New England Trophoblastic Disease Center 15 134/135 (99%) patients with stage III FIGO anatomic disease (pulmonary metastases) experienced a complete remission. Success with low‐risk metastatic disease and single‐agent treatment was attained in 80.9% with the remainder responding to combination chemotherapy and/or local pulmonary resection. Two methotrexate administration options are: 1) methotrexate 0.4 mg/Kg IV or IM daily for 5 days; and 2) pulse methotrexate 40 mg/m 2 IM weekly. 14 Pulse treatment without folinic acid rescue was elected for this patient.

A normal pregnancy can be anticipated 12 months following successful chemotherapeutic treatment of complete molar gestation without increased risk of obstetric complications. 24 In the New England Trophoblastic Disease Center registry 24 of 1234 subsequent pregnancies following molar gestation, the risk for repeat mole was approximately one in 100. There is a small increased risk for secondary tumors following chemotherapy for gestational trophoblastic tumor. 25

The current patient presentation with vaginal bleeding and refractory stage 2 hypertension represents an atypical manifestation of low‐risk metastatic gestational trophoblastic disease. As noted, β‐hCG may sometimes act as a weak thyroid stimulator, and this patient's level of 448,300 mIU/mL probably accounted for her biochemical hyperthyroidism. Moreover, although BPs as high as 215/81 mm Hg exhibited the wide pulse pressure characteristic of hyperthyroidism, the lack of pretreatment tachycardia or response to two, three, and four drug antihypertensive regimes was unusual. Asymptomatic hypertension was the solitary clinical manifestation of her hyperthyroid condition. This was probably due to the acute and transitory nature of this disturbance, but its persistence and refractoriness to what should have been an effective antihypertensive drug regimen before methotrexate administration was quite disturbing to her physician‐husband. If preeclampsia was contributing to her hypertension, more rapid alleviation might have been expected after the uterine evacuation. Instead, her stage 2 hypertension, β‐hCG levels, biochemical hyperthyroidism, and pulmonary metastases all melted away within a month following initiation of pulsed single‐agent methotrexate. Her prognosis for a future pregnancy would be excellent, but probably an undesired circumstance, given her age.

References

- 1. ACOG Practice Bulleting #53 . Diagnosis and treatment of gestational trophoblastic disease. Committee on Practice Bulletins‐Gynecology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologist. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:1365–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moodley M, Tunky K, Moodley J. Gestational trophoblastic syndrome: an audit of 112 patients. A South African experience. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003;13:234–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP. Pathogenesis of gestational trophoblastic neoplasms. Pathobiol Annu. 1981;11:391–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berek JS, Hacker NF. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasi. In: Berek JA, Hacker JA, eds. Practical Gynecologic Oncology. 3rd ed. New York , NY : Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2000:615–638. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kajii T, Ohama K. Androgenetic origin of hydatidiform mole. Nature. 1977;268:633–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP, DuBeshter B, et al. Management of complete molar pregnancy. J Reprod Med. 1987;32:634–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goldstein DP, Berkowitz RS. Current management of complete and partial molar pregnancy. J Reprod Med. 1994;39:139–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hoskins WJ, Perez CA, Young RC. Principles and Practice of Gynecologic Oncology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia , PA : Lippincott‐Raven; 1997:1048. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Davies TF, Larsen PR. Thyrotoxicosis. In: Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, Melmed S, et al. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 10th ed. New York , NY : WB Saunders; 2002: 410–411. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pekonen F, Alfthan H, Stenman UH, et al. Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and thyroid function in early human pregnancy: circadian variation and evidence for intrinsic thyrotropic activity of HCG. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;66:853–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davies TF, Platzer M. hCG‐induced TSH receptor activation and growth acceleration in FRTL‐5 thyroid cells. Endocrinology. 1986;118:2149–2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tomer Y, Huber GK, Davies TF. Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) interacts directly with recombinant human TSH receptors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;74:1477–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hershman JM. Human chorionic gonadotropin and the thyroid: hyperemesis gravidarum and trophoblastic tumors. Thyroid. 1999;9:653–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Silverberg J, O'Donnell J, Sugenoya A, et al. Effect of human chorionic gonadotropin on human thyroid tissue in vitro. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1978;46:420–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vaitukaitis JL. Ectopic hormonal secretion and reproductive dysfunction. In: Yen SSC, Jaffe RB, eds. Reproductive Endocrinology, Physiology, Pathophysiology and Clinical Management. 3rd ed. Philadelphia , PA : WB Saunders Co; 1991:795–806. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Amir SM, Osathanondh R, Berkowitz RS, et al. Human chorionic gonadotropin and thyroid function in patients with hydatidiform mole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;150:723–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP. Presentation and Management of Molar Pregnanc. In: Hancock BW, Newlands ES, Berkowitz RS, eds. Gestational Trophoblastic Disease. London , England : Chapman and Hall; 1997:127–142. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morrow CP, Kletzky OA, Disaia PJ, et al. Clinical and laboratory correlates of molar pregnancy and trophoblastic disease. Am J Obstet Gyencol. 1977;128:424–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Galton VA, Inggar SH, Jimenez‐Fonseca J, et al. Alterations in thyroid hormone economy in patients with hydatidiform mole. J Clin Invest. 1971;50:1345–1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hertz R. Interference with estrogen‐induced tissue growth in the chick genital tract by a folic acid antagonist. Science. 1948;107:300–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lurain JR. Pharmacotherapy of gestational trophoblastic disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2003;4:2005–2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Newlands ES, Paradinas FJ, Fisher RA. Recent advances in gestational trophoblastic disease. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1999;13:225–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gestational trophoblastic disease . Report of a WHO Scientific Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1983;692:7–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Berkowitz RS, Im SS, Bernstein MR, et al. Gestational trophoblastic disease. Subsequent pregnancy outcome, including repeat molar pregnancy. J Reprod Med. 1998;43:81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rustin GJ, Newlands ES, Lutz JM, et al. Combination but not single agent methotrexate chemotherapy for gestational trophoblastic tumors increases the incidence of second tumors. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2769–2773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]