Abstract

In order to survive, organisms must effectively respond to the challenge of maintaining their physiological integrity in the face of an ever-changing environment. Preserving this homeostasis critically relies on adaptive behavior. In this review, we consider recent frameworks that extend classical homeostatic control via reflex arcs to include more flexible forms of adaptive behavior and that take interoceptive context, experiences and expectations into account. Specifically, we define a landscape for computational models of interoception, body regulation and forecasting, address these models’ unique challenges in relation to translational research efforts, and discuss what they can teach us about cognition as well as physical and mental health.

Keywords: Homeostasis, Allostasis, Active Inference, Predictive Coding, Reinforcement Learning, Computational Psychiatry

From reflexes to flexible, adaptive control

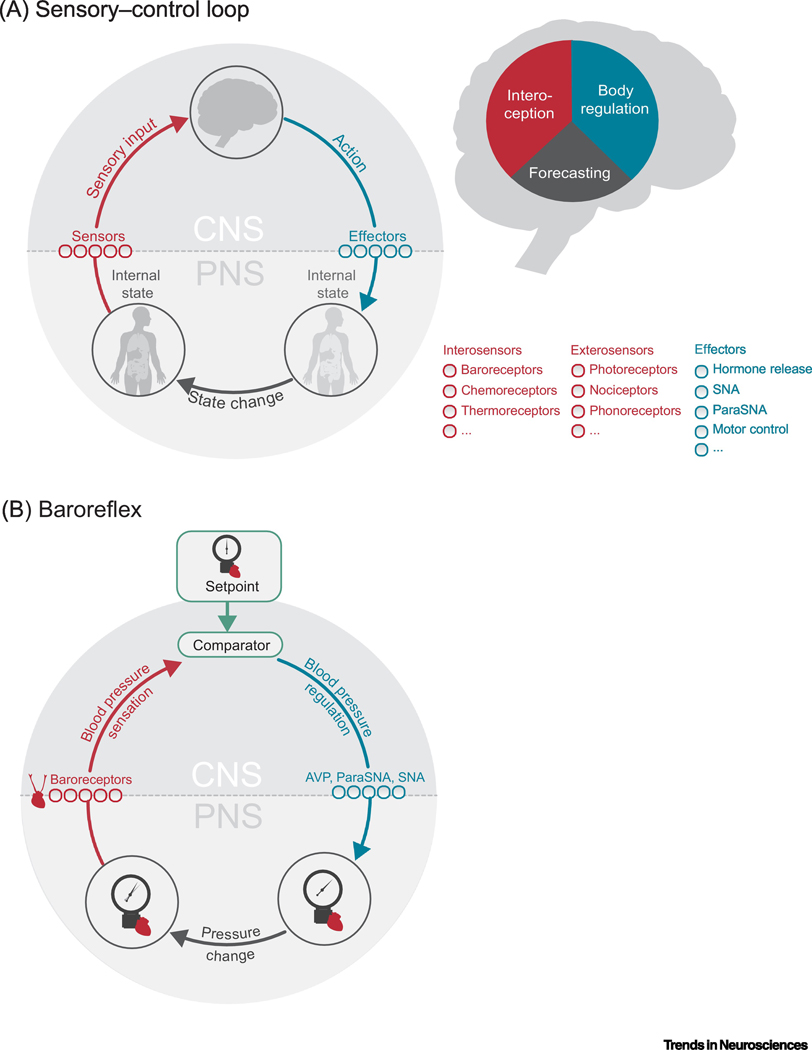

Organisms are constantly confronted with the challenge of maintaining their physiological integrity in the face of an ever-changing environment [1,2]. Behaviors aimed at preserving this homeostasis (see Glossary) and, therefore, survival critically need to be adaptive. To act adaptively, an organism has to translate information about the past and current environment acquired via its sensors into appropriately adjusted actions. Importantly, these actions will affect the environment and, thereby, future sensory inputs. Adaptive behavior thus forms a closed loop between the environment, the sensors, and the effectors – the sensory-control loop (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Schematic of the homeostatic sensory-control loop.

A. Left: An organism translates incoming information about an internal state (red arrow) from its sensors into appropriately adjusted actions, executed by its effectors (blue arrow). Internal states can thereby be informed by both intero-sensors and extero-sensors. These actions, in turn, alter the internal state (state change, grey arrow) and, therefore, the future sensory inputs, resulting in a circular relationship between states, sensations and actions. Right: It is assumed that the CNS forms internal models of the sensory-control loop or specific parts of it. Here, we cover three types of internal models: (i) Models of interoception that describe how internal states can be inferred from sensory signals, (ii) models of body regulation that describe how appropriate actions are selected based on internal states and (iii) models of forecasting that describe how actions lead to changes in the internal states. B. Example of a sensory-control loop: The reflex arc of blood pressure control via the baroreflex: Sensory signals from arterial and cardiopulmonary stretch receptors, baroreceptors, trigger responses in the CNS that result in short-term down-regulation of blood pressure via barosensitive autonomic efferents in the hypothalamus, brainstem, and spinal cord [3,4]. For example, excitatory efferents from the NTS (i) activate inhibitory efferents in the dorsal motor vagal nucleus leading to peripheral parasympathetic activation and (ii) stimulate medullary projections to hypothalamus which inhibit AVP release, collectively reducing blood pressure and heart rate. Abbreviations: CNS: central nervous system; PNS: peripheral nervous system; ParaSNA: Parasympathetic Nervous System Activation; SNA: Sympathetic Nervous System Activation; AVP: arginine vasopressin.

The simplest form of homeostatic sensory-control loop is the classical reflex arc. In reflexes, deviations between sensory inputs and internal setpoints trigger predefined ‘hard-wired’ (re)actions. A classic example is the baroreflex. Here, a detected increase in blood pressure, signaled via baroreceptors, triggers a reaction in the central nervous system (CNS) that results in a short-term down-regulation of blood pressure via barosensitive autonomic efferents [3,4] (Figure 1B)1.

Control via the simple reflex arc is adaptive but limited. This becomes a disadvantage when the environment is dynamic, and under specific contexts the default reaction is no longer beneficial. Accordingly, control mechanisms have been proposed that make reflexes more flexible by allowing an organism to temporarily move away from its setpoint (predictive homeostasis) or by changing the setpoints themselves (allostasis), e.g., in anticipation of a future perturbation[5]. This can be seen for instance when animals increase their body temperature in anticipation of a cold sensation [6]. In fact, there is substantial evidence that homeostatic control in humans and many animal species is more flexible than originally assumed, adjusting to the context [7–10], expected future events [6] or even abstract beliefs [11].

One of the key open questions is how the CNS achieves flexible homeostatic control. Specifically, what type of information needs to represented and what computations does the CNS perform? Several recent computational frameworks have begun to address these questions.

In this review, we use the sensory-control loop as a guiding principle to relate computational frameworks to one another and discuss what aspect of sensory-control they address. This will lead us from models that describe the perception of internal states based on sensory data (models of interoception), to models that describe the process of selecting the right action in different contexts (models of body regulation), to models that aim to predict the future consequences of these actions on the body (models of forecasting). Once these frameworks are outlined, we will then address key aspects of interoception and body regulation that we believe need to be addressed in current formulations. Finally, we ask what these computational models can teach us about cognition, mental health, and disease.

Computational models of interoception and body regulation

Internal states

Before describing the computational modeling landscape, let us first define the concept of an internal state. In the sensory-control loop outlined in Figure 1A, internal states produce sensory signals that lead to actions that, in turn, change internal states. This framework is very similar to how scientists have long thought about motor control [12]. Except that, in motor control, states are typically external, such as the position of a flying ball, while here states are internal. They represent physiological conditions, such as body temperature, pain, itch, blood pressure, micturition, intestinal tension, heart rate, osmotic balance, or hormonal concentration, that evolve over time [3,13]. These conditions can thus be either directly observable from sensory data or more hidden or abstract, requiring the inference and integration of multiple sensory channels. The sensors signaling these internal states are also predominantly internal, including chemoreceptors, mechanoreceptors, baroreceptors, thermoreceptors, and many other molecularly-specified sensory afferents [14]. However, they may also include external sensory channels (vision, audition, touch, taste, smell, proprioceptors) if these carry relevant information about the internal state (e.g., see [15]). Similarly, actions typically represent internal control mechanisms, like hormone release, adjustments of sympathetic or parasympathetic activity, or the activation or inhibition of specific homeostatic reflex arcs. Importantly, actions can also include motor commands, if those affect the relevant internal state. For instance, getting up to close the window when feeling cold can be considered an elaborate form of thermoregulation. We refer to the overall process of selecting and executing actions that affect the internal state as body regulation.

The anatomy of computational models

The sensory-control loop can be divided into three stages (Figure 1A): (1) internal states cause sensory signals; (2) a regulatory action aimed towards maintaining or regaining homeostasis is selected and executed; (3) the action changes the internal state. While this is a representation of the ‘real world’, it is typically thought that the central nervous system (CNS) forms an implicit or explicit representation of this cycle or mappings between its different parts. We call this an internal model, because it refers to what the CNS computes and represents, not the contingencies in the real word. The idea that the CNS forms internal models has a long history [12] and relates to a central theme in Cybernetics suggesting that ‘every good regulator of a system must be a model of that system’ [16].

A number of recent models can be roughly assigned to the three parts of the sensory-control loop: Specifically, we cover models that describe how an internal state could be inferred from the sensory information (models of interoception), how appropriate actions could be selected to regulate the body (models of body regulation) and how internal states evolve as a consequence of the chosen actions and as a function of their own internal dynamics (models of forecasting) (Figure 1A).

Although it may seem obvious, it is worth underscoring that these processes are highly interdependent; furthermore, certain models may cover more than one stage of the sensory-control loop. However, emphasizing this separation provides a helpful guide through the forest of different modeling approaches. It also offers insight into the processing of ascending information and the signaling of downstream action signals in the anatomically distinct afferent and efferent neural pathways [14].

Computational models of interoception

Sensory information is noisy and often ambiguous. This means that the exact internal state that causes the sensory signals may not be known (it cannot be directly observed). The CNS could address this problem by inferring the internal state based on all available information (different sensory modalities, context, prior experiences). Formally, this means it is inferring the internal states most likely to have caused its sensations, which is why this type of internal model is also called an inverse model (reverse arrow in Figure 2A) or generative model, because it guesses how the observed sensory data were generated [17–19]. The inferred internal state, which is really only an estimate of the real internal state, is what is typically called the percept (or in the case of internal states, the interocept). Interoception and exteroception can thus be distinguished based on the type of state that is being inferred – internal or external – rather than the specific sensory channels that contributed to the inference.

Figure 2. Schematic of computational models of interoception.

A. Top left: Computational models of interoception are inverse models, as indicated by the black dotted arrow. Large circle: Schematic illustration of interoception: New incoming sensory information, which depends on the current internal state, the likelihood function, is combined with a-priori expectations about the internal state, the prior, to form a percept, the posterior. The prior thereby results from an internal model of the state of the body in the world – in short, a model of the body. B: Schematic representation of Bayes’ Theorem. The posterior can be computed in a statistically optimal manner by calculating the product of the likelihood and the prior, here illustrated with the example of Gaussian distributions. Importantly, Bayes’ Theorem takes the uncertainty of information into account. Information with high prior precision (left) will be weighted more than information with low prior precision (right). C: Schematic representation of Predictive Coding: Brain areas at higher levels of the hierarchy send predictions about the expected input to lower levels. Every mismatch between predicted and actual input at lower levels will be processed as a prediction error that is propagated up the hierarchy. Predictive Coding requires a minimum of two classes of neurons: Representation neurons signaling predictions (green circles) and prediction error neurons (black triangle). At the lowest level of the hierarchy the input is the actual sensory data. Predictive Coding is hypothesized to be a general feature of many living organisms, and therefore, it could be interrogated across the spectrum of animal species.

Another important aspect to consider is that the internal generative model is thought to include an organism’s general (explicit and implicit) knowledge about the structure and dynamics of the world and the body within. In a specific context, this knowledge expresses (although often in an unconscious way) prior expectations. For instance, human observers have implicit assumptions that light is coming from above, which shapes the way they interpret shadows [20]. In the context of interoception, these priors replace set points in that they define which internal states are likely to be occupied by an organism, e.g., which body temperature ranges are likely to be observed. Naturally, these likely states tend to coincide with the ones that promote an organism’s survival. The extent to which organisms are born with ‘hard-wired’ biological priors about basic bodily states such as temperature or osmolarity [21], and which priors are learned through experience remains an intriguing open question that might be resolved by developmental studies [22].

Interoceptive Bayesian inference

Interoceptive Bayesian inference addresses the question of how the CNS could compute its estimate of an internal state (Marr’s computational level [23]). Specifically, Bayes’ Theorem is a rule in statistics that describes how different types of noisy information could be combined in an optimal manner. In the context of perception it proposes how the CNS could combine the current sensory data, called likelihood, with a prior expectations, to arrive at an estimate of the internal state, called posterior [24] (Figure 2A). Importantly, it takes the uncertainty of each information source into account (Figure 2B). If sensory information is noisy, the prior will be assigned greater importance, and vice versa.

Bayes’ Theorem thus describes what an ‘ideal’ agent would do, which is why this is sometimes called an ideal observer model. As such, it has been used as a benchmark to which real behavior can be compared. There is significant evidence that in many situations humans behave close to what would be expected from an ideal observer, e.g., when combining different sensory information [25–27], integrating past experiences [28–30], or even abstract beliefs [20,31].

Interoceptive Predictive Coding

Bayesian inference does not come with a prescription of how the computations discussed in the previous section are implemented. Suggestions abound of how the CNS could approximate Bayesian inference with neuronal algorithms [18,32–34]. One of the most prominent ones is (Bayesian) Predictive Coding [35–38].

Interoceptive Predictive Coding assumes the existence of specific neuronal populations, called prediction error units, which compute the difference between the a-priori expected, that is, the predicted, and the actual (sensory) inputs at multiple connected hierarchical layers [18,19] (Figure 2C). This prediction error is then propagated up the hierarchy and serves to update the original prediction of that level [35,37,39]. Prediction error units are thus similar to the comparator in a classical reflex arc, where deviations between inputs and setpoints trigger actions (except that here, the setpoint is a prediction) [35–37]. Furthermore, while prediction errors can trigger actions (see Active Inference), in Predictive Coding they are used as a learning signal to improve future predictions [35–37].

The hierarchical structure of Predictive Coding allows representation at various levels of abstraction: Low-level predictions are about the exact form of the sensory input, higher-level predictions are more abstract, integrating information across multiple sensory domains or information about the context. Predictive coding thus poses the hypothesis that the internal model is not represented in a single brain area, but in the connectivity of hierarchical populations of neurons from early sensory areas to higher level viscero-motor cortices, where each area processes a hierarchically distinct aspect of the internal state. To date, the full interoceptive brain network underlying this implementation has not been identified.

Computational models of homeostatic and allostatic body regulation

One of the most challenging tasks the CNS has to perform is selecting the right action under any given circumstance. Internal models of this kind are called forward models because they describe the process of moving from sensation to action. Here we focus on frameworks that extend classical feedback control [40], as in reflex arcs, by providing the means to adjust actions to the context or expected future events to subserve a specific goal. One of the primary goals for an organism (formally, its objective function) should be to keep its body alive (i.e., survival). In a concrete situation, this can be specified as reaching or maintaining desired internal states [41,42] (Figure 3A). A number of concrete formulations describe how organisms could learn to transition from their current internal state to the desired state, e.g., by minimizing the overall cost [43,44], maximizing long-term expected rewards [42,45–48] or minimizing surprise about sensory inputs [39,49–51]. Here, we will focus on two concrete frameworks to highlight their differences and commonalities: homeostatic reinforcement learning (HRL) and interoceptive active inference (IAI).

Figure 3. Schematic of computational models of body regulation.

A. Example of Homeostatic Reinforcement Learning (HRL) in the sensory-control loop. In HRL, actions that reduce the difference between current internal states and desired internal states (drives) are processed as being rewarding. By comparing the estimated reward value to the actual experienced reward, a reward prediction error (RPE) can be computed which is used to update future value estimates and inform action selection. Agents can thus learn to maximize rewards by minimizing drive to maintain homeostasis. See [21,42] for a detailed discussion. B. Example of Interoceptive Active Inference (IAI) in the sensory-control loop. IAI extends Predictive Coding to include action selection. Specifically, actions signaled by descending predictions are thought to represent desired internal states. Actions are then selected to fulfill predictions which bring the actual internal state closer to the desired one.

Homeostatic reinforcement learning

HRL proposes a way how actions that reduce the distance between the current and desired internal state – the drive – can be reinforced. Here, the concept of reward in classical reinforcement learning is redefined in a homeostatic manner, namely as a reduction in drive. This means that actions that are predicted to bring the internal state closer to the desired state are perceived as being rewarding [42,52]. Homeostatic action selection can then be conceptualized as the maximization of long-term expected rewards as in classical reinforcement learning schemes, except that here these actions will lead an organism towards a desired internal state (Figure 3A) (see [42] for a detailed formulation).

Interoceptive Active Inference

IAI makes an alternative proposal in which agents minimize surprise to maintain homeostasis (based on the Free Energy Principle [53]). This is better understood in the context of the Interoceptive Predictive Coding scheme, introduced earlier. During interoception the prediction errors between predicted and actual sensory inputs are used to update an internal model of the body (learning) and infer the internal state. IAI extends Predictive Coding by suggesting that the predictions themselves represent a desired future internal state. Instead of updating the prediction, an organism can thus select actions that fulfill the predictions to bring the internal state closer to the desired state. (This corresponds to reversing the inverse model, turning it into a forward model again.) Both strategies, learning and action selection, thus reduce the prediction error and therefore minimize ‘the surprise’.

An important rationale behind IAI is that prior predictions are thought to represent internal states an organism is likely going to occupy and that are therefore congruent with survival, such as maintaining certain body temperatures or being hydrated. Choosing actions that fulfill these genetic and experience-dependent priors thus naturally provide a means to maintain homeostasis and allostasis. In other words, ‘Under active inference, agents stay alive by predicting the states that keep them alive, and act to fulfill those predictions.’[54] (Figure 3B) (see [39,49,55] for a detailed discussion).

Comparison and implementation

These frameworks can seem conceptually different. However, at a computational level they are quite similar, since the drive in HRL can be formally re-expressed as surprise in IAI [21,42]. Consequently, both frameworks are capable of explaining a range of control mechanisms that extend simple reflex arcs, such as adjusting reflexes in response to a learned context or in anticipation of predicted changes, incorporating Pavlovian, habitual and goal-directed homeostatic responses [42,49].

Nevertheless, there are important differences when considering the algorithmic and neuroanatomical implementation of these models. Predictive Coding and IAI assume that predictions and prediction errors are explicitly represented in neuronal populations (but see [56]), where the highest level of the hierarchy is represented in viscero-motor regions in the subgenual cortex, anterior/mid cingulate cortices, insular cortex and orbitofrontal cortex. Those areas project to subcortical control areas, such as the hypothalamus, the periaqueductal grey or the parabrachial nucleus [37,57]. Here, the descending predictions influence internal setpoints directly. This can result in an activation or suppression of low-level reflex arcs via prediction error units that detect a discrepancy between the predictions and the sensory inputs (Figure 3B). In line with this, cortical neurons in the rostral insula, medial prefrontal cortex and the primary motor cortex were recently found to influence parasympathetic and sympathetic output to the stomach [58]. In contrast, reinforcement learning could also be performed in the absence of an explicit representation of internal states, e.g., via direct connections between sensors signaling internal states and areas involved in the computation of reward such as dopaminergic midbrain neurons. For instance, orexin neurons that project from the lateral hypothalamus to the ventral tegmental area (VTA) [59] and receptors for ghrelin, leptin or insulin in the VTA could provide interfaces for a direct influence of internal states on reward computations [60], while the expected drive reduction effects could be signaled via the opioid system [42]. Notably, this assumes that internal states can be signaled directly and do not need to be inferred, raising the possibility that this type of control could be performed in the absence of an interocept. More complex (goal-directed) forms of HRL, e.g. when the framework is extended to emotions, will, however, likely require the inference and explicit representation of internal states. While different controllers (Reflexes, Pavlovian, Instrumental) thus compete or collaborate to achieve homeostatic control in an HRL framework, IAI proposes the integration of these control mechanisms in different hierarchical layers (for a more detailed comparison see [21,54]). While it has been difficult to arbitrate between competing models of homeostatic regulation at a computational level, these implementational differences may serve as the basis for future research programs aiming to delineate the most useful models of body regulation on the basis of experimental evidence.

Computational models of forecasting

The CNS predicts not only how internal states change as a consequence of actions, but also as a function of their own internal dynamics (forecasting). Certain forms of anticipatory processing indicate that many species engage in forecasting, for instance, when drinking is terminated minutes before any appreciable change in blood osmolarity [61]. One way to formalize forecasting is by suggesting that an agent is running an internal model of the body forward in time (e.g., from action to outcome), which corresponds to simulating the future sensory consequences of actions, but also the internal dynamics of the body. Another way of formulating forecasting would be to run the model backward (from outcome to action). This would involve assuming a future desired state and then simulating all the possible actions that would lead to that state to select the most promising one. The later makes forecasting part of an action selection process. Indeed, many models of body regulation implicitly assume that certain organisms are capable of forecasting, including HRL [42] and IAI [49]. Yet, there are few frameworks that have formalized forecasting [62,63], especially in the internal domain [64].

Building accurate models of interoception and body regulation

While the computational models discussed here are largely inspired by existing descriptions of exteroception, learning and motor control, there are a number of peculiarities of internal states that models of interoception and body regulation will need to address.

Receiver characteristics and multisensory integration

Internal organs are sparsely innervated relative to exteroceptive organs [65]. In addition, the nervous system is constantly fielding, sorting, classifying, and responding to signals from dozens of sensory sources that need to be integrated. Cardiovascular information, for instance, is spread across various sensors that separately encode the occurrence of a cardiac pulsation, the strength of pulsation, associated blood pressures, and neurovascular afferents that carry mechanical and chemical information ensuing from the pulsation [66,67]. Heartbeats are thus transduced in a distributed manner quite distinct from vision or audition. Moreover, multisensory signaling also occurs across different internal and external domains, e.g., cardiac and respiratory signals are highly intertwined during sympathoexcitation. Adequate computational models thus need to be able to incorporate both the integration of multiple sensory signals and their possibly distributed representation.

Time scales and speeds

Internal signaling unfolds across a wide range of timescales and speeds [68,69]. Cardiac and respiratory processes occur at fast timescales (e.g. heart rate decelerations due to vagal input (seconds), accelerations due to adrenaline release (seconds to minutes), tachypnea due to sympathoexcitation (seconds)), whereas gastrointestinal processes occur over minutes to hours (e.g. blood glucose concentration modulation after food ingestion, blood osmolarity changes after fluid intake). Immunological processes are typically even slower, spanning minutes to weeks (delayed hypersensitivity reactions, chronic immune activation) but they can also occur within seconds (e.g. anaphylactic reactions). The interaction of signals across timescales poses a complex challenge to computational models, which often assume rapid stimulus-response associative learning over short timescales [62] (but see [42,70,71]).

Oscillations and neuro-vascular coupling:

Several internal processes are controlled by their own intrinsic pacemakers that result in an oscillatory electrical activity which is signaled to the brain (e.g., heart: ~1Hz, breathing ~0.2Hz, gastrointestinal tract: ~0.05Hz) [72]. Recent work suggests that these regular sensory inputs directly influence brain dynamics and higher-order cognition [67]. At the local blood flow level, neuro-vascular regulation is typically thought of as being orchestrated by neuronal activity mediated largely via astrocytes [73]. However, predictions that hemodynamic influences can reciprocally alter the gain (and sensory discriminability) of cortical circuits [74] are supported by empirical evidence of neuronally-specific cardiovascular oscillations [75]. These alternative signaling pathways are typically not considered, although they could be integrated as gating signals at various computational stages [76].

Conscious perception and metacognition

Internal states and their regulation are largely unconscious. Still, they affect a wide variety of appraisal processes. For instance, the change in interoceptive signals (e.g. heart rate acceleration) and their conscious perception (e.g. interoceptive awareness) can combine to guide cognition [77]. Moreover, metacognitive beliefs about the efficacy of one’s own body regulation may influence both cognitive processes as well as the development of certain physiological symptoms [78], suggesting that modeling an individual’s response to internal states and their appraisal may be as important as modeling the signals themselves.

Addressing the potential and challenges of computational frameworks

What can be learned from these computational models? We believe that among their biggest contributions is their potential for informing comparative analyses and translational research: (1) across homologous systems in distinct species, (2) across different levels of description from cellular to systems levels, (3) in describing bidirectional influences of internal states on cognition and (4) in describing how maladaptive computations may result in disease. Each of these comparative and translational aspects poses unique challenges for the type of data and methodologies required in interoception research.

Comparative analyses across species

To date, there is a chasm between animal and human studies on interoception and body regulation. This is partly due to previous arguments that interoception in humans is very different from interoception in simpler animals [79], and partly because human interoception studies have relied heavily on verbal self-reports, which cannot be obtained in animals.

Specifically, the revolution in molecular circuit-mapping tools and the development of opto-and chemo-genetic tools to selectively manipulate specific cell-types has powered systems neuroscience preferentially in one model system, the C57BL/6J laboratory mouse. This affords the identification of many of the cellular and molecular mechanisms of interoception [66,80,81]. However, it is difficult to assess, for example, interoceptive awareness or mindful processing of respiratory sensation in a mouse. At the same time, common human neuroscience methods, such as electroencephalography, or functional magnetic resonance imaging do not allow access to the cellular and circuit levels ultimately necessary to understanding the computations carried out by specific neural populations. Computational models could help identify and evaluate processes that can be quantified via discrete parameter estimates (e.g. precision, learning rate or bias), across animal models and humans [82].

This type of research requires coordinated multidisciplinary efforts, including closely related manipulations across species, while remaining cognizant of their anatomical differences. For instance, there are direct connections from the parabrachial nucleus to the insula and ventromedial prefrontal cortex in rats [83], but not in monkeys [67,84]. It will therefore be necessary to include animal models that are more closely related to humans than mus musculus, e.g. macaque and marmoset non-human primates, and to compare them to humans experiencing similar experimental manipulations.

Linking levels of description

Computational frameworks can be used to describe processes across levels of granularity, from molecules to neural systems and behavior [82,85,86]. While no model currently links all levels of analysis, there are a few promising examples that have connected the activity of neuronal populations to behavior and symptoms leading to advances in the field of psychiatry [87] and neurology [88,89]. Little work exists, however, that aims at integrating the peripheral nervous system (PNS) into these frameworks. One key hurdle is a limited understanding of how physiological processes at the anatomical and cellular-levels can be validated using computational models, which makes it particularly hard to validate computational models with experimental evidence. In addition, while there are increasingly large-scale endeavors, like the cell census effort of the BRAIN initiative (www.biccn.org), to map and specify cell types in the various brain regions across species [90], there are currently no parallel endeavors for a functional map of the PNS. Such a cell-type based atlasing effort where all cells of the PNS—and their associated axons—are visualized throughout the body in situ within a whole-body common coordinate framework, including their connectivity to the CNS and their associated transcriptional cell types, will be imperative to build biophysically informed descriptions of body-brain interactions. This endeavor stands and falls with the development of more advanced recording- and manipulation-techniques of the PNS using either optical or electrical strategies (e.g., multi-photon, Neuropixels) and targeted perturbations (e.g., vagus nerve stimulation, thermostimulation, cardiac perturbations) [68,91]

Linking internal states to cognition

Lately, there has been a wealth of empirical studies that showed a much broader influence of internal signals on cognition than typically assumed [77], including effects on visual detection [92], the valuation of internal and external rewards [93,94], decision-making, attention [95,96] or the sense of selfhood [97,98]. Not surprisingly, computational models have begun to permeate these areas. Predictive Coding, IAI, and HRL have been used to formulate theories of emotions [35,99,100], a sense of self and embodiment [35,101] and value-based decision-making [52,102].

From health to disease: Clinical implications of models of interoception and body control

The application of computational models to understanding disease processes has given rise to the emerging field of Computational Psychiatry [82,103–105]. From a conceptual viewpoint, it seems plausible that failures to accurately represent one’s internal environment or choose appropriate actions may be linked to the expression of specific psychiatric conditions, including depression [78], schizophrenia [106,107], anxiety [50,68], or symptom expression across disorders [108] (See [109] for a detailed discussion). The pervasiveness of bodily symptom expression across the spectrum of psychiatric disorders has helped to motivate the extension of tools from Computational Psychiatry to address interoception and body regulation, via an approach termed Computational Psychosomatics [41]. Predictive coding, IAI, or HRL have been used to provide conceptual frameworks for understanding, for instance, anxiety and depression [50], somatic symptom disorders [110], chronic pain, fibromyalgia, as well as functional psychiatric [111], addictive [52,112,113] and neurological disorders [114].

One of the promises of the field is that computational models will yield individual and quantifiable markers of basic neural computations (e.g., in the form of parameter estimates) that are linked to illness pathophysiology. Akin to a blood test, the idea is that these ‘computational biomarkers’ may point toward an individual maladaptive function useful for diagnosis, prognosis or treatment [115].

While the potential of computational models is considerable, at present there is little empirical work testing such models’ predictions [31,95,116]. To become clinically relevant, computational models of interoception will need to be rigorously translated through a development pipeline not unlike that employed during novel drug identification [117–119]. That is, effective computational biomarkers must demonstrate their utility in improving the diagnosis, monitoring, prediction, prognosis, risk susceptibility or treatment, ideally, in individual patients.

Concluding remarks

We have charted a landscape of computational models of interoception, body regulation, and forecasting via the sensory-control loop. Doing so facilitates the combination of empirical tools with theoretical models to better understand how information about the world and the body optimally integrates to inform action selection and maintain health and survival. Nevertheless, this effort faces several challenges due to the unique structure and control of interoceptive signals. Future progress may depend on how well these existing methods improve our understanding of physical and mental health when combined with novel measurement and manipulation techniques (see Outstanding Questions).

Outstanding Questions.

What aspects of body regulation are predetermined by evolutionary constraints and which ones are learned from experience?

To what extent does body regulation require explicit representations of internal states?

How do bodily signals affect neural computations in the peripheral and central nervous systems?

What types of computational models are suitable to translate between animal and human studies?

How can computational markers of interoception inform and improve physical and mental health?

Highlights.

The sensory-control loop can be used as a guiding principle to align different computational models of interoception and body regulation.

Recent computational frameworks focus on formulating body regulation via flexible, adaptive control mechanisms that extend classical reflex arcs.

The perception and regulation of interoceptive signals poses tangible and unique challenges for computational modeling.

Concrete computational frameworks of brain-body interactions hold great potential for translational research.

Modeling approaches could be applied to develop testable ‘computational biomarkers’ to support diagnostic, prognostic or treatment efforts, particularly in individuals with symptoms originating from maladaptive brain-body interactions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants of the NIH blueprint for Neuroscience Research workshop on “The Science of Interoception and Its Roles in Nervous System” that took place in Bethesda, Maryland on April 16–17, 2019. We furthermore thank Lilian Weber and Klaas Enno Stephan for valuable discussions that inspired this paper. SSK is supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grant K23MH112949. SSK and MPP are supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) Center grant 1P20GM121312, and The William K. Warren Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Glossary

- Allostasis

The process of achieving stability, or homeostasis, by dynamically adjusting homeostatic setpoints through neural, physiological, or behavioral change. Allostasis is often associated with prospective control, where preemptive actions are taken e.g., by shifting the setpoints themselves, to adjust prior to an anticipated homeostatic perturbation and to avoid dyshomeostatic future states.

- Body regulation

The overarching process of selecting and executing actions that affect the internal state (physiological condition) of the body. Body regulation includes internal control mechanisms, like hormone release, but can also include motor commands, if those affect the relevant internal state.

- Central nervous system

the part of the nervous system consisting mainly of populations of nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord.

- Exteroception

The process whereby the nervous system senses, interprets and integrates signals from the external world to form an estimate about continuously-evolving external states of the environment across conscious and unconscious levels (see also perception).

- Forecasting

The process of predicting future internal and external states, by taking into account how states change as a consequence of actions and due to their own intrinsic dynamics.

- Generative model

In the context of perception, a generative model is an internal model that specifies how sensory data are generated from hidden states by incorporating prior knowledge about the structure of the environment and the body. Sometimes also referred to as model of the body in the world.

- Homeostasis

The active processes by which a living organism maintains physiological states within a range conducive to survival in the face of environmental perturbations. Classical Homeostasis was original associated with reactive control in response to external perturbation. More recent descriptions suggest that homeostasis can also be predictive by selecting actions that shift the state of an organism away from the setpoint in anticipation of a predicted future deviation.

- Internal/physiological state

A specific physiological condition of the body, such as temperature, blood pressure, or hormonal concentration, that continuously evolves over time. States can represent the condition of a single sensory modality, or the integrated result of multiple sensory signals. In many cases internal states may not be directly observable, which requires an organism to infer the state based on the available information (see definition of perception).

- Interoception

The overall process of how the nervous system senses, interprets, and integrates signals about the body, providing a moment-by-moment mapping of the body’s internal landscape (internal states) across conscious and unconscious levels (see definition of perception).

- Motor control

The processes concerned with the relationship between sensory signals and motor commands, including the transformation from motor commands to their sensory consequences and the transformation from sensory signals to motor commands.

- Perception

The process of how the nervous system senses, interprets and integrates signals about the outside world and inside the body, providing a moment-by-moment representation of the state of an organism within its surrounding environment. Perception can be regarded as an (unconscious and conscious) inference process whereby an organism is inferring the state of the body and the world based on sensory data and its internal generative model of the body in the world. Exteroception and interoception can represent subareas of perception with a focus on either internal or external states, respectively.

- Peripheral nervous system

the part of the nervous system consisting mainly of populations of neurons outside of the brain and spinal cord. It contains both the autonomic and somatic nervous systems.

- Sensory signals

Signals related to an external or internal state after transduction by a sensory receptor (such as chemoreceptors, baroreceptors, photoreceptors etc).

Footnotes

This represents a simplification; the baroreflex is not as straightforward as one might think [120].

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cannon WB (1939) The wisdom of the body, Norton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramsay DS and Woods SC (2014) Clarifying the Roles of Homeostasis and Allostasis in Physiological Regulation. Psychol Rev 121, 225–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robertson D. et al. (2012) Primer on the Autonomic Nervous System, Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guyenet PG (2006) The sympathetic control of blood pressure. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 7, 335–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McEwen BS (2017) Allostasis and the Epigenetics of Brain and Body Health Over the Life Course: The Brain on Stress. JAMA Psychiatry 74, 551–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mansfield JG and Cunningham CL (1980) Conditioning and extinction of tolerance to the hypothermic effect of ethanol in rats. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol 94, 962–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies KJA (2016) Adaptive homeostasis. Mol. Aspects Med 49, 1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies KJA (2018) Cardiovascular adaptive homeostasis in exercise. Front. Physiol 9, 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peterson LW and Artis D. (2014) Intestinal epithelial cells: Regulators of barrier function and immune homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol 14, 141–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liston A. and Gray DHD (2014) Homeostatic control of regulatory T cell diversity. Nat. Rev. Immunol 14, 154–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wager TD and Atlas LY (2015) The neuroscience of placebo effects: connecting context, learning and health. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 16, 403–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolpert DM and Ghahramani Z. (2000) Computational principles of movement neuroscience. 3, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Craig AD (2002) How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 3, 655–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berntson et al. , Neural circuits of interoception. Trends Neurosci. same issue, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khalsa SS et al. (2009) The pathways of interoceptive awareness. Nat. Neurosci 12, 1494–1496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conant RC and Ross Ashby W. (1970) Every good regulator of a system must be a model of that system. Int. J. Syst. Sci 1, 89–97 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barlow H. (1961) Possible principles underlying the transformation of sensory messages. In Sensory Communication (W R, ed), pp. 217–234, MIT Press [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao RPN and Ballard DH (1999) Predictive Coding in the visual cortex: a functional interpretation of some extra-classical receptive-field effects. Nat. Neurosci 2, 79–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friston K. and Kiebel S. (2009) Predictive coding under the free-energy principle. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci 364, 1211–1221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams WJ et al. (2004) Experience can change the “light-from-above” prior. Nat. Neurosci 7, 1057–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hulme OJ et al. (2019) Neurocomputational theories of homeostatic control. Phys. Life Rev 31, 214–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berkes P. (2011) Spontaneous Cortical Activity Reveals Hallmarks of an Optimal Internal Model of the Environment. Science 331, 83–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marr D. (1982) Vision, Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knill DC and Richards W. (1996) Perception as Bayesian inference, Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alais D. and Burr D. (2004) Ventriloquist Effect Results from Near-Optimal Bimodal Integration. Curr. Biol 14, 257–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ernst MO and Banks MS (2002) Humans integrate visual and haptic information in a statistically optimal fashion. Nature 415, 429–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ernst MO and Bülthoff HH (2004) Merging the senses into a robust percept. Trends Cogn. Sci 8, 162–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petzschner FH et al. (2015) A Bayesian perspective on magnitude estimation. Trends Cogn. Sci 19, 285–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petzschner FH and Glasauer S. (2011) Iterative Bayesian estimation as an explanation for range and regression effects: A study on human path integration. J. Neurosci 31, 17220–17229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Lange FP et al. (2018) How Do Expectations Shape Perception? Perceptual Consequences of Expectation. Trends Cogn. Sci 22, 764–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grahl A. et al. (2018) The periaqueductal gray and Bayesian integration in placebo analgesia. Elife 7, 1–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pouget A. et al. (2013) Probabilistic brains: knowns and unknowns. Nat. Neurosci 16, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma WJ et al. (2006) Bayesian inference with probabilistic population codes. Nat. Neurosci 9, 1432–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olshausen BA and Field DJ (1996) Emergence of simple-cell receptive field properties by learning a sparse code for natural Images. Nature 381, 607–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seth AK (2013) Interoceptive inference, emotion, and the embodied self. Trends Cogn. Sci 17, 565–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seth AK et al. (2012) An interoceptive predictive coding model of conscious presence. Front. Psychol 3, 1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barrett LF and Simmons WK (2015) Interoceptive predictions in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 16, 419–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aitchison L. and Lengyel M. (2017) With or without you: predictive coding and Bayesian inference in the brain. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol 46, 219–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seth AK and Friston KJ (2016) Active interoceptive inference and the emotional brain. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci 371, 2016007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ashby WR (1961) An introduction to cybernetics, Chapman and Hall Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petzschner FH et al. (2017) Computational Psychosomatics and Computational Psychiatry: Toward a Joint Framework for Differential Diagnosis. Biol. Psychiatry 82, 421–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keramati M. and Gutkin B. (2014) Homeostatic reinforcement learning for integrating reward collection and physiological stability. Elife 3, 1–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Todorov E. and Jordan MI (2002) Optimal feedback control as a theory of motor coordination. Nat. Neurosci 5, 1226–1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Todorov E. (2004) Optimality principles in sensorimotor control. Nat. Neurosci 7, 907–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Busemeyer J. et al. (2002) Motivational underpinnings of utility in decision making: decision field theory analysis of deprivation and satiation. In Emotional cognition: from brain to behaviour (Moore S and Oaksford M, eds), pp. 197–218, John Benjamins [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singh S. et al. (2010) Intrinsically motivated reinforcement learning: an evolutionary perspective. IEEE Trans. Auton. Ment. Dev 2, 70–82 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dranias M. et al. Dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic value systems in conditioning and outcome-specific revaluation. Brain Res. 1238, 239–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berridge K. (2012) From prediction error to incentive salience: mesolimbic computation of reward motivation. Eur. J. Neurosci 35, 1124–1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pezzulo G. et al. (2015) Active Inference, homeostatic regulation and adaptive behavioural control. Prog. Neurobiol 134, 17–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paulus MP et al. (2019) An Active Inference Approach to Interoceptive Psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol 15, 97–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Allen M. et al. (2019) In the Body’s Eye: The Computational Anatomy of Interoceptive Inference. bioRxiv DOI: 10.1101/603928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keramati M. et al. (2017) Cocaine Addiction as a Homeostatic Reinforcement Learning Disorder. 124, 130–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Friston K. (2010) The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nat. Rev. Neurosci 11, 127–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morville T. et al. (2018) The Homeostatic Logic of Reward. bioRxiv DOI: 10.1101/242974 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Friston K. (2009) The free-energy principle: a rough guide to the brain? Trends Cogn. Sci 13, 293–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brette R. (2020) Is coding a relevant metaphor for the brain ? Behav. Brain Sci 42, 1–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Quadt L. et al. (2018) The neurobiology of interoception in health and disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1428, 112–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Levinthal DJ and Strick PL (2020) Multiple areas of the cerebral cortex influence the stomach. PNAS 117, 13078–13083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Burdakov D. (2019) Neuropharmacology Reactive and predictive homeostasis : Roles of orexin / hypocretin neurons. Neuropharmacology 154, 61–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Palmiter RD (2007) Is dopamine a physiologically relevant mediator of feeding behavior? Trends Neurosci. 30, 375–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zimmerman CA et al. (2016) Thirst neurons anticipate the homeostatic consequences of eating and drinking. Nature 537, 680–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sutton RS and Barto AG (1998) Reinforcement learning: An introduction, MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Botvinick M. and Toussaint M. (2012) Planning as inference. Trends Cogn. Sci 16, 485–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Penny W. and Stephan K. (2014), A dynamic Bayesian Model of Homeostatic Control., in 3rd International Conference on Adaptive and Intelligent System (ICAIS), pp. 60–69 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jänig W. (2006) The Integrative Action of the Autonomic Nervous System. In Neurobiology of Homeostasis Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zeng W-Z et al. (2018) PIEZOs Mediate Neuronal Sensing of Blood Pressure and the Baroreceptor Reflex. Science 362, 464–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Azzalini D. et al. (2019) Visceral Signals Shape Brain Dynamics and Cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci 23, 488–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Khalsa SS et al. (2018) Interoception and Mental Health: A Roadmap. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 3, 501–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Quigley et al. , Functions of Interoception: From Energy Regulation to Experience of the Self. Trends Neurosci. same issue, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schedlowski M. and Pacheco-López G. (2010) The learned immune response: Pavlov and beyond. Brain. Behav. Immun 24, 176–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fernandes AB et al. (2020) Postingestive Modulation of Food Seeking Depends on Vagus-Mediated Dopamine Neuron Activity. Neuron 106, 778–788.e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Furness JB (2012) The enteric nervous system and neurogastroenterology. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol 9, 286–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Iadecola C. (2017) The neurovascular unit coming: a journey through neurovascular coupling in health and disease. Neuron 96, 17–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moore CI and Cao R. (2008) The Hemo-Neural Hypothesis: On The Role of Blood Flow in Information Processing. J Neurophysiol. 99, 2035–2047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mosher CP et al. (2020) Cellular Classes in the Human Brain Revealed In Vivo by Heartbeat-Related Modulation of the Extracellular Action Potential Waveform. Cell Rep. 30, 3536–3551.e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Philips RT et al. (2016) Vascular dynamics aid a coupled neurovascular network learn sparse independent features: A computational model. Front. Neural Circuits 10, 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Critchley HS and Garfinkel SN (2018) The influence of physiological signals on cognition. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci 19, 13–18 [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stephan KE et al. (2016) Allostatic Self-efficacy: A Metacognitive Theory of Dyshomeostasis-Induced Fatigue and Depression. Front. Hum. Neurosci 10, 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Craig AD (2009) How do you feel — now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 10, 59–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Williams EK et al. (2016) Sensory neurons that detect stretch and nutrients in the digestive system. Cell 166, 209–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zimmerman CA et al. (2019) A gut-to-brain signal of fluid osmolarity controls thirst satiation. Nature 568, 98–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Huys QJM et al. (2016) Computational psychiatry as a bridge from neuroscience to clinical applications. Nat. Neurosci 19, 404–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shipley MT and Sanders MS (1982) Special senses are really special: evidence for a reciprocal, bilateral pathway between insular cortex and nucleus parabrachialis. Brain Res. Bull 8, 493–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pritchard TC et al. (2000) Projections of the parabrachial nucleus in the Old World monkey. Exp. Neurol 165, 101–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Roberts JA et al. (2017) Clinical Applications of Stochastic Dynamic Models of the Brain, Part I: A Primer. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2, 216–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Moran RJ et al. (2011) An in vivo assay of synaptic function mediating human cognition. Curr. Biol 21, 1320–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Maia TV and Frank MJ (2011) From reinforcement learning models to psychiatric and neurological disorders. Nat. Neurosci 14, 154–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Frank MJ et al. (2004) By carrot or by stick: cognitive reinforcement learning in parkinsonism. Science 306, 1940–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Frank MJ (2005) Dynamic dopamine modulation in the basal ganglia: a neurocomputational account of cognitive deficits in medicated and nonmedicated Parkinsonism. J. Cogn. Neurosci 17, 51–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hodge RD et al. (2019) Conserved cell types with divergent features in human versus mouse cortex. Nature 573, 61–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Weng et al. , Interventions and manipulations of interoception. Trends Neurosci. same issue, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Park H-D et al. (2014) Spontaneous fluctuations in neural responses to heartbeats predict visual detection. Nat. Neurosci 17, 612–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cabanac M. (1971) Physiological role of pleasure. Science (80-. ) 173, 1103–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Azzalini D. et al. (2019) Fluctuations in the homeostatic neural circuitry influence consistency in choices between cultural goods. bioRxiv DOI: 10.1101/776047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Petzschner FH et al. (2019) Focus of attention modulates the heartbeat evoked potential. Neuroimage 186, 595–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Piech RM et al. (2010) All I saw was the cake. Hunger effects on attentional capture by visual food cues. Appetite 54, 579–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Babo-Rebelo M. et al. (2016) Neural Responses to Heartbeats in the Default Network Encode the Self in Spontaneous Thoughts. J. Neurosci 36, 7829–7840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tallon-Baudry C. et al. (2018) The neural monitoring of visceral inputs, rather than attention, accounts for first- person perspective in conscious vision. Cortex 102, 139–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Feldman Barrett L. (2017) The theory of constructed emotion: an active inference account of interoception and categorization. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci 12, 1–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Seth AK and Friston KJ (2016) Active interoceptive inference and the emotional brain. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 371, 20160007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Allen M. and Friston KJ (2018) From cognitivism to autopoiesis: towards a computational framework for the embodied mind. Synthese 195, 2459–2482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Juechems K. and Summerfield C. (2019) Where does value come from? Trends Cogn. Sci 23, 836–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Read Montague P. et al. (2012) Computational psychiatry. Trends Cogn. Sci 16, 72–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Friston KJ et al. (2017) Computational Nosology and Precision Psychiatry. Comput. Psychiatry 1, 2–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Redish AD and Gordon JA (2016) Computational Psychiatry: New Perspectives on Mental Illness, [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jardri R. and Denève S. (2013) Circular inferences in schizophrenia. Brain 136, 3227–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Adams RA et al. (2016) Computational Psychiatry: Towards a mathematically informed understanding of mental illness. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 87, 53–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Smith R. et al. (2020) An active inference model reveals dysfunctional interoceptive precision in psychopathology. medRxiv DOI: 10.1101/2020.06.03.20121343 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bonaz et al. , Diseases, disorders, and comorbidities of interoception. Trends Neurosci. same issue, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Dimsdale J. et al. (2013) Somatic symptom disorder: an important change in DSM. J Psychosom Res. 75, 223–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Edwards MJ et al. (2012) A Bayesian account of “hysteria.” Brain 135, 3495–3512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Koob GF (2013) Negative reinforcement in drug addiction: The darkness within. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol 23, 559–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ahmed SH and Koob GF (2005) Transition to drug addiction: A negative reinforcement model based on an allostatic decrease in reward function. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 180, 473–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Espay AJ et al. (2018) Current Concepts in Diagnosis and Treatment of Functional Neurological Disorders. JAMA Neurol. 75, 1132–1141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Petrella JR et al. (2019) Computational Causal Modeling of the Dynamic Biomarker Cascade in Alzheimer’s Disease. Comput. Math. Methods Med 2019, 1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Van Elk M. et al. (2014) Suppression of the auditory N1-component for heartbeat-related sounds reflects interoceptive predictive coding. Biol. Psychol 99, 172–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Paulus MP et al. (2016) A Roadmap for the Development of Applied Computational Psychiatry. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 1, 386–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Stephan KE et al. (2015) Translational Perspectives for Computational Neuroimaging. Neuron 87, 716–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Browning M. et al. (2020) Realizing the Clinical Potential of Computational Psychiatry: Report From the Banbury Center Meeting, February 2019. Biol. Psychiatry DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Chapleau M. (2011) Baroreceptor reflexes. In Primer on the autonomic nervous system (3rd edn) (Robertson D. et al., eds), pp. 161–165, Academic Press [Google Scholar]