Abstract

Human factor XIa (hFXIa) has emerged as an attractive target for development of new anticoagulants that promise higher level of safety. Different strategies have been adopted so far for the design of anti-hFXIa molecules including competitive and non-competitive inhibition. Of these, allosteric dysfunction of hFXIa’s active site is especially promising because of the possibility of controlled reduction in activity that may offer a route to safer anticoagulants. In this work, we assess fragment-based design approach to realize a group of novel allosteric hFXIa inhibitors. Starting with our earlier discovery that sulfated quinazolinone (QAO) bind in the heparin-binding site of hFXIa, we developed a group of two dozen dimeric sulfated QAOs with intervening linkers that displayed a progressive variation in inhibition potency. In direct opposition to the traditional wisdom, increasing linker flexibility led to higher potency, which could be explained by computational studies. Sulfated QAO 19S was identified as the most potent and selective inhibitor of hFXIa. Enzyme inhibition studies revealed that 19S utilizes a non-competitive mechanism of action, which was supported by fluorescence studies showing a classic sigmoidal binding profile. Studies with selected mutants of hFXIa indicated that sulfated QAOs bind in heparin-binding site of the catalytic domain of hFXIa. Overall, the approach of fragment-based design offers considerable promise for designing heparin-binding site-directed allosteric inhibitors of hFXIa.

Keywords: Fragment-based drug design, coagulation factors, anticoagulants, heparins, allosterism

Introduction

Thrombin and factor Xa (FXa), two enzymes belonging to the common pathway of coagulation, are the primary targets of inhibitors used in the clinic today.1,2 Growing evidence points to the feasibility and value of targeting enzymes belonging to the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways of coagulation. One such enzyme that is gaining more enhanced emphasis due to its apparent safety features is factor XIa (FXIa).3–6 Several animal model studies indicate that the inhibition of FXIa reduces thrombosis with minimal increase in bleeding.7–10 Alternatively, selective inhibitors of FXIa impact the pathological consequence (thrombosis) but not the physiological consequence of clot formation (hemostasis). Hence, there is significant interest in identifying novel strategies of discovering inhibitors of FXIa.

Human FXIa (hFXIa) is a 160 kDa disulfide-linked homodimer composed of a catalytic domain and the four apple domains that are linked through a disulfide bond to form the dimer.11,12. The catalytic domain and the A3 domain of FXIa each possess a heparin-binding site (HBS).13–15 Positively charged residues K252, K253 and K255 form the HBS of the A3 domain, whereas K259, R530, R532, K536 and K540 residues form the HBS of the catalytic domain. The former is known to partake in the heparin-mediated antithrombin inhibition of FXIa through the template-based mechanism,14,15 the latter is known to be more important in the allosteric modulation of FXIa functional activity.7,16–19

The most often used approach of targeting hFXIa is orthosteric inhibition. This has led to the design/discovery of several heterocyclic agents and natural products as highly promising inhibitors.20–33 Prominent among these are the tetrahydroisoquinoline- (Figure 1), pyridazine-, pyridazinone-, pyridine-, pyrimidine-and imidazole-based agents that bind in the active site of hFXIa.21,24,25,29 Another scaffold that is highly promising is the 10–12-atom macrocyclic scaffold (Figure 1) that has yielded orally active agents too.20,22,26–28 Early in the discovery phase, a natural product clavatidine was identified as a reasonably potent inhibitor of FXIa.31 Interestingly, a fragment-based strategy was implemented to discover active site inhibitors that have a 5-phenyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide scaffold.23 The class of orthosteric inhibitors display a wide range of potencies, of which a few, e.g., BMS-962212, EP-7041 and ONO-7684, are being studied in clinical trials.

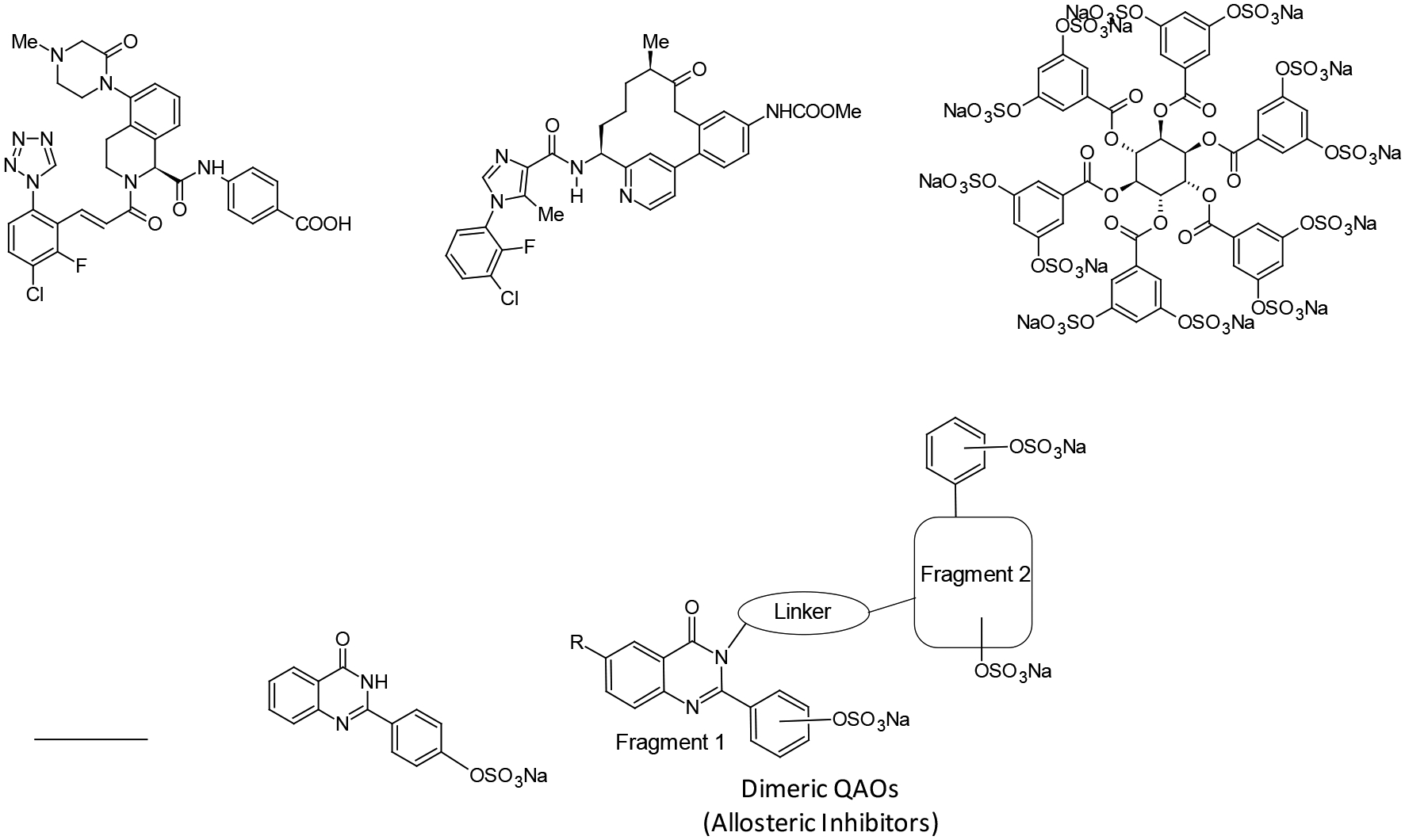

Figure 1.

Examples of factor XIa (FXIa) inhibitors developed so far and sulfated dimeric quinazolinones developed in this work. Several inhibitors, e.g., BMS-962212 and pyridine-based macrocycles, have been developed to bind in the active site of FXIa. Very few allosteric inhibitors have been developed, e.g., SCI. This work relates to the development of a library of molecules starting from monomeric sulfated QAO fragment 2S. Here, four classes of sulfated QAOs with aliphatic, aromatic and triazole linkers were developed and studied.

In direct contrast orthosteric inhibitors, few allosteric inhibitors have been designed/discovered. Whereas orthosteric inhibition affords dose of the inhibitor as the only means of varying enzyme activity, allosteric inhibition offers the promise of controlling FXIa activity by modulating the efficacy of inhibition (ΔY) also. Alternatively, orthosteric inhibitors fully inhibit target enzyme at saturation (ΔY = >90%); in contrast, appropriately designed allosteric inhibitors can regulate target enzyme at saturation (ΔY = 25–75%). Thus, allosterism is the only means of discovering partial inhibitors, which may lead to much higher level of safety for coagulation proteases (FXIa and others), thereby eliminating the high risk of bleeding besetting all clinically used anticoagulants today.34

Unfortunately, there are no obvious routes of discovering allosteric partial inhibitors. We have employed various strategies to discover such agents including the dual element strategy16,19 and the heparin-mimicking strategy.7,17,18 Of these, the latter group has led to the identification of SCI (Figure 1),7 while the former have yielded sulfated quinazolinone (QAO) and sulfated benzofuran scaffolds.16,19 The major advantage of these inhibitors was their hydrophobic scaffold (Figure 1), which was completely different from highly hydrophilic, polysulfated, natural ligand heparin that binds in the HBS of hFXIa. We reasoned that a computational fragment-based approach may help improve potency for sulfated QAO inhibitors, which offer an excellent framework for designing/discovering allosteric regulators of FXIa. This work describes the implementation of this fragment-based approach so as to derive ~40-fold more potent allosteric QAOs. We developed a group of 28 dimeric sulfated QAOs with intervening linkers that displayed a progressive variation in inhibition potency. In fact, we discovered that the traditional wisdom of increasing linker flexibility leading to poor potency does not hold true for this group of molecules inhibiting hFXIa. Interestingly, the inhibition profiles could be explained by computational studies. We also show that certain related linkers, e.g., more rigid, aromatic linkers, are not preferred, which points to the interesting landscape of heparin-binding site of hFXIa. Overall, this work shows that fragment-based approach offers considerable promise for the design of heparin-binding site-directed allosteric inhibitors of hFXIa.

Results

Fragment-based screening using molecular modeling.

Our earlier studies led to identification of three allosteric inhibitors of hFXIa including sulfated QAOs,16 sulfated pentagalloyl glucosides17,18 and sulfated benzofurans.19 These molecules are structurally different and appear to utilize different allosteric sites. Our earlier work indicated that of these different sites, sulfated QAOs induced inhibition through the catalytic domain alone (FXIa-CD) because the A3 domain was not found to be important for activity.16 Hence, we assessed the catalytic domain of hFXIa (PDB ID: 1ZOM) for fragment-based drug design process.

First, the entire surface of FXIa’s catalytic domain was scanned for the plausible sites of binding for sulfated QAO 2S, a prototypic fragment. Binding pockets near several positively charged residues including K62, K107, K127, R147, K175, R185, and K202 were identified as viable candidate sites (Figure 2A). Using these residues as the loci and the length of sulfated QAO as the radius (~14 Å), seven centroids were identified as potential sites of binding (Figure 2A). In combination, this fragment search covered nearly 98% of the surface. Incidentally, the surface remaining unscreened (~2%) did not encompass any positively charged residue, although polar residues were present.

Figure 2.

Fragment-based docking and scoring approach to identify potential sites of binding on hFXIa. A) hFXIa surface was divided into putative binding domains that could accommodate sulfated QAO 2S in the vicinity of Arg/Lys residues. Different colored domains represent different binding domains around a basic residue (shown in spheres, green color by atom). B) Sulfated QAO 2S preferentially occupied two distinct binding sites BS1 and BS2. C) The preferential interaction arose from multiple hydrogen bond (shown as spheres, white color by atom) and non-bonded (shown as sticks, pink color by atom) interactions with residues constituting BS1 and BS2. These residues include basic residues as well as polar residues.

Sulfated QAO 2S was docked onto each of the seven potential sites using a dual filter, genetic algorithm-based docking protocol developed in our laboratory earlier for sulfated molecules.35–37 The electronic steering engineered by the presence of the lone sulfate group of the fragment was found to induce favorable interaction with several sites, however, hydrophobic and steric forces generated differential binding interactions. Two parameters, GOLDscore and RMSD (root mean square deviation), which correspond to the strength of interaction and consistency of binding, respectively, were used to parse the different geometries. The results revealed that the interaction of sulfated QAO was significantly biased towards two sites BS1 and BS2 (Figure 2B). These two sites are approximately 9 – 12 Å away from each other, which offers the possibility of fragment-based design of dimeric sulfated QAO agents.

Interestingly, R173 was one of the residues making a key hydrogen bonding interaction for both binding modes. Previous studies on human thrombin had shown that this residue plays an important role in the recognition of a sulfated benzofuran inhibitor and its replacement (R173→A) led to a defect of ~22-fold.37,38 This implied that the two fragments could perhaps be linked through an appropriate linker to develop novel inhibitors with higher potency. Thus, we embarked on the program of synthesizing dimers of sulfated QAO 4S—21S, 24S—29S and 33S—36S that rely on either aliphatic, aromatic or triazole linkers.

To first assess whether a sulfated QAO monomer binds and inhibits hFXIa, we synthesized 2S in 2 steps following our earlier work employing microwave-based sulfation.39,30 Dose-dependence of hFXIa inhibition using the chromogenic substrate hydrolysis assay led to an IC50 of 375±21 μM (not shown). Likewise, fluorescence-based binding affinity titrations yielded hFXIa affinity of 365±4 μM (see below). Although this potency appears to be low, taking the small size of the fragment into consideration, we reasoned that it bodes well for the further design.

Synthesis of the Library of Diverse Dimeric Sulfated QAOs.

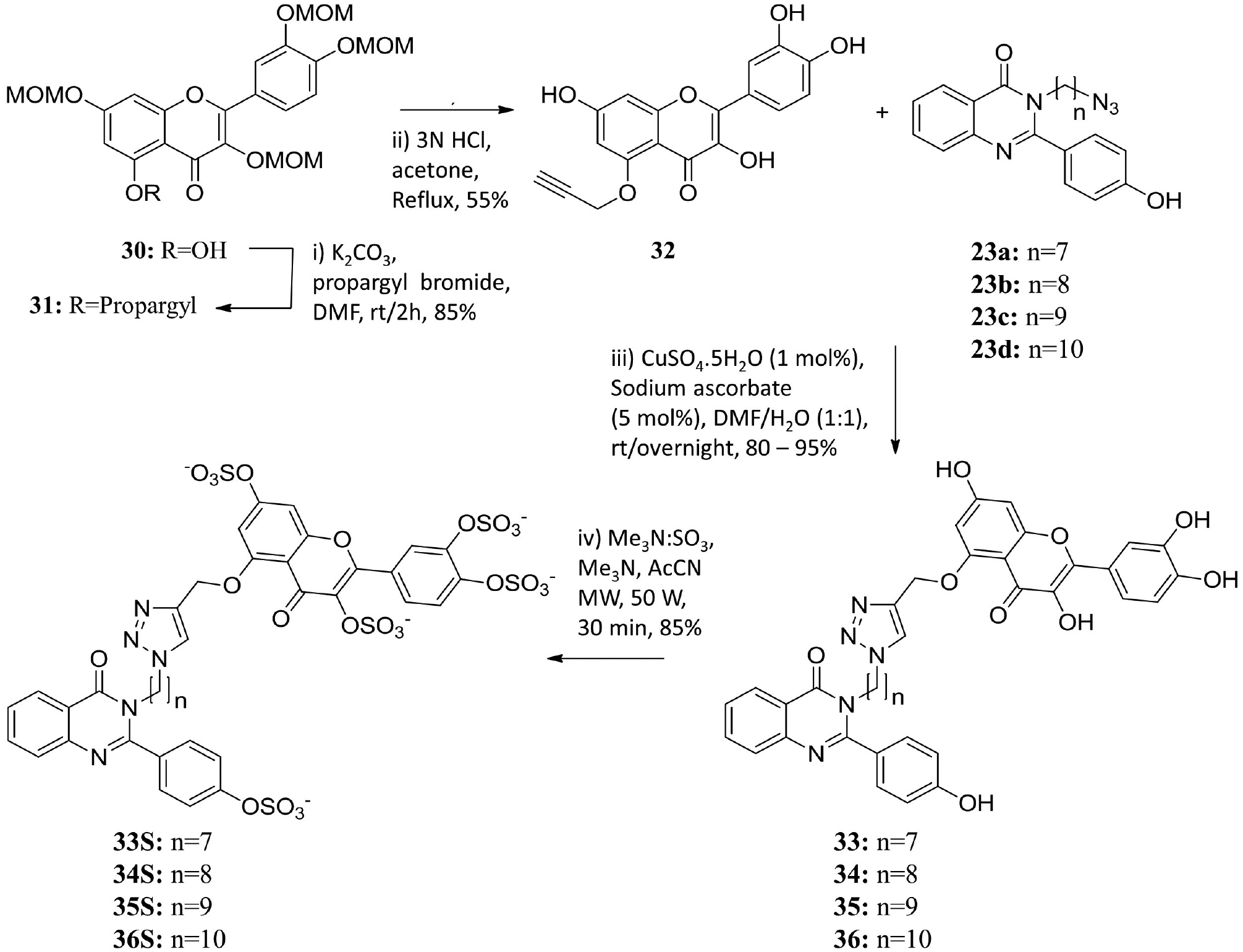

We synthesized a total of 28 sulfated QAO dimers carrying structurally diverse linkers with varying lengths and geometries. The diversity of linkers arises from their aromatic, aliphatic and triazole structures. The aromatic (4S—8S) and aliphatic (9S—21S) linker containing sulfated QAOs were synthesized using a nucleophilic substitution reaction (Scheme 1), whereas the triazole-based sulfated QAOs 24S—29S and 33S—36S were assembled using a copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction (Schemes 2 and 3).16,41 Whereas the majority of synthesized library members are homo-dimeric, 33S—36S could be considered as hetero-dimeric because one of the monomers is a flavonoid scaffold. Likewise, diversity also arises from the length of the different linkers. Whereas some are short (e.g., aromatic and alkenic linkers), others are much longer (e.g., dodecyl linker).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Sulfated QAOs 4S-21S.

aNote: 18S contains a methoxy and a sulfate group each.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of sulfated QAOs 24S – 29S.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of sulfated QAOs 33S – 36S.

For the aromatic and aliphatic linker containing dimers, the QAO core scaffold was synthesized using a condensation reaction between anthranilamide and suitably substituted benzaldehyde to obtain a small group of QAO monomers (Scheme 1), which was followed by phenol protection and substitutive dimerization with target α,ω-dibromo linkers. These dimeric QAOs were then de-protected using lithium hydroxide and sulfated under microwave conditions with sulfur trioxide–amine complex in the presence of an organic base, as reported earlier (Scheme 1).16,39 For the triazole linker containing dimers, the copper-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction was exploited. Appropriate QAO or flavonoid alkynes and azides (Schemes 2 and 3) were synthesized from corresponding monomers using acetylation of phenolic groups and nucleophilic displacement strategy followed by deacetylation. The corresponding alkynes and azides were coupled in the presence of aqueous CuSO4 and sodium ascorbate giving 1,2,3-triazoles 24—29 (Scheme 2) and 33—36 (Scheme 3), which were sulfated under microwave conditions to obtain final sulfated homo- (24S—29S, Scheme 2) or hetero- dimers (33S—36S, Scheme 3). The final sulfated QAOs were obtained in >95% purity as demonstrated by UPLC analysis.

Sulfated QAO Inhibition of hFXIa and Related Proteases.

Sulfated QAOs were studied for inhibition of hFXIa and related enzymes using chromogenic substrate hydrolysis assays under optimal conditions defined for each enzyme (see Methods). The dose-dependence of protease activity was fitted using the logistic equation to calculate the IC50 (Table 1). The o, m and p-xylene linker containing sulfated QAOs, possessing 4, 5 and 6 intervening atoms, respectively, displayed potencies in the range of 57 to 248 μM, which were significantly better than that for the monomeric fragment. Interestingly, the ortho- (7S, 8S) and meta- (5S, 6S) xylene containing inhibitors, which should display bent geometries, displayed better potency than the para- substituted molecule, which represents a linear linker (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inhibition of hFXIa by sulfated QAOs.a

| Inhibitor | LL | IC50 (μM) | ΔY (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4S | 6 | 248±3c | 100±3c |

| 5S | 5 | 60±1 | 92±5 |

| 6S | 5 | 76±1 | 96±6 |

| 7S | 4 | 94±2 | 93±4 |

| 8S | 4 | 57±2 | 87±3 |

| 9S | 4 | 415±10 | 96±7 |

| 10S | 5 | 89±1 | 96±2 |

| 11S | 5 | 49±1 | 92±3 |

| 12S | 5 | 401±22 | 94±16 |

| 13S | 6 | 53±1 | 96±5 |

| 14S | 6 | 34±2 | 87±3 |

| 15S | 6 | 35±1 | 95±3 |

| 16S | 7 | 23±1 | 96±4 |

| 17S | 8 | 20±1 | 81±2 |

| 18S | 9 | 173±1 | 93±4 |

| 19S | 9 | 8.2±0.5 | 101±8 |

| 20S | 10 | 16.6±0.3 | 95±2 |

| 21S | 11 | 14.5±0.8 | 96±6 |

| 24S | 11 | 51±2 | 103±2 |

| 25S | 12 | 39±2 | 100±2 |

| 26S | 13 | 34±2 | 100±4 |

| 27S | 14 | 22±2 | 112±4 |

| 28S | 15 | 30±2 | 98±2 |

| 29S | 16 | 35±2 | 112±4 |

| 33S | 11 | 139±10 | 93±3 |

| 34S | 12 | 133±13 | 92±6 |

| 35S | 13 | 37±4 | 110±8 |

| 36S | 14 | 51±6 | 106±6 |

The IC50 and ΔY values were calculated from nonlinear regression analysis of direct inhibition of hFXIa (see Methods).

LL is linker length, the minimum number of intervening atoms in the linker.

Errors represent ±1 SE.

Considering the above result on the preference of linker with bent geometry, we studied a rigid trans-but-2-ene linker containing sulfated QAO (12S). However, this molecule was no better than the starting fragment. This implied that longer linker length may be important for recognition of both sites of binding. Hence, we synthesized three sulfated QAOs with aliphatic linkers containing 5 intervening atoms. Of the three, the 4-OSO3— substituted QAO (11S) yielded ~7-fold increase in potency as compared to the monomeric fragment, whereas that with the 3-propoxypropane linker (12S) nearly lost all of its potency. This implied that both the position of sulfate group on the two fragments and the linker length are important.

We reasoned that an extended linker would probably serve to place the two QAO fragments better within the two hydrophobic sites. Hence, we synthesized 4-OSO3— substituted sulfated QAOs 13S—21S carrying progressively longer alkylenic linkers. To our surprise, increasing the linker length from 6 to 9 intervening atoms, the IC50 decreased from 34.3 to 8.2 μM, which represent a substantial 10- to 43-fold enhancement in potency over the monomeric fragment (Table 1). Further increase in linker length to 10 and 11 intervening atoms yielded a slight decrease in inhibition potency to 16.6 and 14.5 μM, respectively.

To assess whether introducing hydrogen bonding partners in the linker alter affinity/inhibition properties, we synthesized the library of homodimeric sulfated QAOs 24S—29S containing a triazole linker. This also allowed us to screen extended linker lengths. However, the IC50s did not improve over that measured for 21S. We then synthesized heterodimeric sulfated QAOs 33S—36S, which contain one tetrasulfated flavonoid fragment. Yet, the IC50s of these heterodimeric structures did not yield a better molecule. In fact, the potencies decreased significantly for at least two of these agents (Table 1) suggesting a strong preference for the monosulfated hydrophobic fragments.

To assess the selectivity profile of these compounds, we evaluated inhibition of several serine proteases including thrombin, FVIIa, FIXa, FXa, plasma kallikrein, trypsin and chymotrypsin. Screening was performed using an appropriate chromogenic substrate (see Methods). Briefly, no inhibition of these proteases was observed at concentration as high as 500 μM (>63-fold selectivity, not shown), except for 20S—21S that were found to inhibit FXa and trypsin at >200 μM (>25-fold selectivity, not shown). This implied that the selectivity was maximal when the linker length was 9 atoms. Further increase in linker length led to higher potency against FXa and trypsin, thereby reducing the selectivity. Overall, specific dimeric sulfated QAOs containing defined aliphatic linkers were identified as selective inhibitors of FXIa.

Mechanism of Inhibition of Sulfated QAOs.

Computational studies predicted the site of binding of these inhibitors in the HBS of the catalytic domain of FXIa. This implies an allosteric mode of inhibition. We studied the kinetics of Spectrozyme FXIa hydrolysis by FXIa in the presence of 19S. A characteristic hyperbolic substrate hydrolysis profile was observed (Figure 3), which could be analyzed using the standard Michaelis–Menten to calculate the KM and VMAX. As expected, the KM of Spectrozyme FXIa was found to be invariant as the concentration of 19S was varied from 0 (0.27±0.01 mM) to 120 μM (0.26±0.32 mM), while the VMAX decreased from a high of 36.9±1.5 mAU/min to a low of 9.7±0.37 mAU/min for the same concentration range (Figure 3). This is characteristic of a non-competitive mechanism of inhibition and follows the profiles known for other heparin mimetics reported in the literature to date.16–19,37,38

Figure 3.

Michaelis-Menten kinetics of Spectrozyme FXIa hydrolysis by hFXIa in the presence of sulfated QAO 19S. The initial rate of hydrolysis at various substrate concentrations was measured spectrophotometrically in pH 7.4 buffer at 37°C. Solid lines represent nonlinear regressions using the standard Michaelis equation to yield KM and VMAX.

Sulfated QAO Dimers Induce Allosteric Change in hFXIa.

To further understand whether the non-competitive mechanism results from remote changes induced in the active site of hFXIa, we studied fluorescence properties of active site labeled hFXIa in the presence and absence of sulfated QAOs. Figure 4 shows titrations of sulfated QAO monomer (2S), sulfated QAO dimer (18S) and disulfated QAO dimer (19S) interacting with active site dansylated-hFXIa (EGR-hFXIa). Whereas the monomer displays a hyperbolic interaction profile, the two dimers display a classic sigmoidal interaction profiles alluding to a co-operative phenomenon. Alternatively, this suggests that one of the monomers of a sulfated QAO dimer first binds to hFXIa followed by a conformational change resulting in better binding of the second monomer of the dimer. Because the dansyl group is located in the active site of hFXIa, the conformational change disfavors substrate binding resulting in inhibition.16

Figure 4.

Measurement of affinity of A) sulfated QAO dimers 16S (triangles), 17S (diamonds) and 19S (squares) and B) sulfated QAO monomer 2S (circles) for human plasma factor XIa (FXIa). Titrations were performed using the change in fluorescence of dansyl group present in the active site of FXIa. The emission of dansyl group was measured at 547 nm (λEX = 345nm) in 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 150 mM NaCl and 0.1% PEG8000 at 37°C. Solid lines represent non-linear regressions using either the Hill equation 1 (16S, 17S and 19S) or the standard hyperbolic equation (2S) to obtain the ΔFMAX and KD of binding.

The interaction profiles were analyzed by either the quadratic binding equation (2S) or the three parameter Hill cooperativity equation to calculate the dissociation constant (KD) of binding and the Hill co-operativity coefficient (n). Table 2 lists these parameters. Overall, the KD of the monomer (2S) was ~3.2-fold higher than that for 18S, which in turn was higher by ~18.3-fold than that for 19S. These results further support the concept of bridging monomeric fragments. Additionally, the results highlight the importance of one sulfate group each on two monomers of a dimer.

Table 2.

Binding parameters of sulfated QAOs interacting with hFXIa.a

| Inhibitor | ΔFMAX (%) | n | KD (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2S | −34±1.8b | n/ac | 365±4.2 |

| 18S | 301±1.4 | 4.3±0.5 | 115±6.5 |

| 19S | 265±3.1 | 5.0±0.4 | 19.9±0.5 |

Titrations were performed by adding aliquots of a solution of a sulfated QAO 2S, 18S or 19S to 250 nM FXIa–DEGR in 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 150 mM NaCl and 0.1% PEG8000 at 37 °C and monitoring the change in fluorescence at 547 nm (λEX 345 nm). The maximal fluorescence change (ΔFMAX), Hill coefficient ‘n’, and KD were calculated using nonlinear regressional analysis (see Methods).

Error = ± 1 SE.

not applicable.

Sulfated QAO Dimers Bind in the HBS of the Catalytic Domain.

To identify the site of binding, we utilized three mutants of hFXIa, including a K252A, K253A, K255A mutant and a K529A, R530A, R532A, K535A K539A mutant, which are respectively the HBSs of the A3 and the catalytic domain.13–15 The third chimeric mutant combined these replacements in both HBSs. Figure 5 shows the inhibition profile of sulfated dimer 19S against the three mutants. Whereas the 19S potency against hFXIaA3 (14 μM) and wild type hFXIa (FXIaWT) (20 μM) were very similar, that against hFXIaCD and hFXIaA3-CD decreased nearly 3-fold (Table 3). This indicated that for 19S to bind to hFXIa, the CD is important but A3 domain is not. The ~3-fold loss in potency is not a large change and suggests that other residues that provide binding energy may be involved. These residues could be nearby basic residues as well as hydrophobic or polar residues. Identifying the cohort of residues that contribute binding forces for selective recognition of 19S is important but was not undertaken. Overall, the mutagenesis results support the computational prediction that sulfated QAO fragments would target the HBS of the hFXIa’s CD. The results also support the allosteric mechanism of inhibition deduced through enzyme kinetics.

Figure 5.

Dose-response profiles for 19S inhibition of recombinant wild-type FXIa (FXIaWT) and FXIa proteins carrying alanine replacements of heparin-binding residues in the catalytic domain (FXIaCD), A3 domain (FXIaA3) and both catalytic and A3 domains (FXIaCD&A3) in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% PEG8000 and 0.02% Tween80 at 37 °C. Solid lines represent dose response fits to calculate the potency (IC50) and maximal inhibition efficacy (ΔY).

Table 3.

Inhibition of hFXIa variants by 19S.a

| Mutant | IC50 (μM) | ΔY (%) |

|---|---|---|

| FXIaWT | 20.0±0.8b | 93±3 |

| FXIaA3 | 14.0±0.4 | 99±2 |

| FXIaCD | 34.0±1.5 | 96±3 |

| FXIaCD&A3 | 32.0±1.0 | 105±3 |

The IC50 and ΔY were calculated following nonlinear regression analysis of direct inhibition of hFXIa mutants (see Methods). Inhibition was monitored by spectrophotometric measurements of residual hFXIa activity.

Errors represent ±1 SE.

Do Sulfated QAOs Induce Oligomerization of hFXIa?

Although the results described above clearly demonstrate direct allosterism through the HBS as the reason for inhibition, we reasoned that the unusual structure of sulfated QAOs, especially the long length and aliphatic nature of the linker, could induce oligomerization of hFXIa. Figure 6A shows this mechanism at a theoretical level. Briefly, one monomer of the sulfated QAO dimer could bind to one hFXIa dimer, whereas the other monomer of the sulfated QAO dimer could rope in another hFXIa dimer. Alternatively, sulfated QAO dimers could induce higher order oligomers, e.g., tetramers, hexamers, etc.

Figure 6.

A) Two possible models of sulfated QAO dimer-dependent inhibition of FXIa including allosteric modulation of the FXIa dimer or induction of oligomerization of FXIa dimer. Gradient native PAGE (B) and analytical ultracentrifugation (C) analysis of hFXIa and hFXIa–19S complex. A) Electrophoresis of hFXIa (lane 1), hFXIa–19S complex (lane 2), fFXIa–PMSF (lane 3), FXIa–19S complex–PMSF (lane 4), hFXIa treated with DTT, and hFXIa–19S complex treated with DTT was performed using 4 – 20% gradient gel. B) AUC profiles of hFXIa alone (black) or hFXIa–19S (red) were monitored at A280 and transformed into relative concentrations of each species (CS) at varying sedimentation co-efficient (S). Note: PMSF = phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride.

To test this, we performed native gel electrophoresis. We studied the interaction of 19S with both hFXIa and hFXIa-PMSF, a covalently inhibited enzyme. Figure 6B shows the gel image of hFXIa, FXIa-19S, hFXIa-PMSF and hFXIa-PMSF-19S. Each protein was observed as a single band corresponding to the enzyme’s expected dimeric molecular weight suggesting the absence of higher order oligomers. We also utilized analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC) to assess the oligomerization state of hFXIa and its complex with 19S. hFXIa alone was found to exclusively exist as a dimer (s = 6.6S), which is in line with literature.11,42 More importantly, the hFXIa-19S complex also exhibited dimeric form (s = 6.6S) (Figure 6C). Thus, both native PAGE and AUC experimentation indicate that sulfated QAOs, especially 19S, do not induce dysfunction in hFXIa through induction of higher order oligomers.

Computational Studies Indicate Preference for Aliphatic Linkers of Defined Length.

To assess whether the unique linker length dependence could be computationally explained based on the predicted sites of binding of the monomeric fragment 2S, we studied 18 QAOs with aliphatic linkers and 3 QAOs with the triazole linker. Inhibitors 4S—21S and 24S—26S were modeled and docked onto FXIa’s CD using GOLD.35–38 For each inhibitor, the highest scoring 20 poses were selected and analyzed in detail. Table 4 lists the average GOLDScore of poses. Inhibitor 19S displayed the best score supporting the solution experiments on its FXIa inhibition potential. More importantly, as a group a significant correlation was noted between the GOLDScore and IC50 with a correlation coefficient of ~0.6 (Figure 7A).

Table 4:

Fragment based structural design of sulfated QAO inhibitors for Factor XIa.

| Inhibitor | LBDa (Å) | GOLDScoreb | Hbondsc | Interacting residuesc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4S | 6.4 | 105.3 | 6 | R171, R185, R224 |

| 5S | 6.7 | 106.6 | 6 | R171, H174, R185, R224 |

| 6S | 6.4 | 100.0 | 9 | R173, R224 |

| 7S | 5.8 | 93.7 | 9 | K170, R171, R224 |

| 8S | 5.8 | 105.0 | 9 | R171, R173, R185, R224 |

| 9S | 4.6 | 102.6 | 8 | R171, Q221, R224 |

| 10S | 6.4 | 104.6 | 7 | R171, R173, H174, R224 |

| 11S | 7.1 | 109.1 | 10 | K170, R173, R185, R224 |

| 12S | 5.9 | 103.7 | 7 | R171, R185, R224 |

| 13S | 8.9 | 109.2 | 10 | K170, R171, R173, R185, R224 |

| 14S | 8.4 | 108.3 | 10 | R171, R173, R185, R224 |

| 15S | 8.6 | 107.3 | 10 | R171, R173, R185, R224 |

| 16S | 9.9 | 109.6 | 11 | R171, R173, R185, R224 |

| 17S | 10.9 | 108.6 | 9 | R171, R173, R224 |

| 18S | 11.6 | 94.3 | 4 | R173, R224 |

| 19S | 11.4 | 114.7 | 10 | K170, R171, R173, R185, R224 |

| 20S | 12.9 | 107.1 | 6 | R171, R173, R224 |

| 21S | 12.5 | 108.5 | 8 | R171, R173, Q221, R224 |

| 24S | NAd | 102.3 | NA | NA |

| 25S | NA | 99.0 | NA | NA |

| 26S | NA | 96.1 | NA | NA |

LBD is the average distance between the two nitrogen atoms of each QAO fragment for the top 20 poses.

Average GOLDScore of top 20 poses from 1000 GA runs of each molecule.

The number of consistent hydrogen bonds and interacting residues for top 20 docked poses.

Not applicable because of inconsistency of binding.

Figure 7.

Computational results on sulfated QAOs support biochemical inhibition results. A) The GOLDScores following genetic algorithm docking and scoring studies show significant correlation with log(IC50) (r2 of ~0.6) suggesting a good possibility of inhibition arising from dual mode binding of the sulfated QAO dimers. Note: Sulfated QAOs with IC50 >200 were not included in the analysis. The best binding poses of sulfated QAOs 4S – 12S, 13S – 19S, and 20S – 21S are shown in panels B, C and D, respectively. Each molecule is shown in a different color representation. Inhibitor 19S is orange colored and it is also shown as reference in panel C. Panels E, F and G represent zoomed in versions of panels B, C, and D, respectively. As the linker length increased to 10 atoms and above, there was a noticeable ~60° difference in orientation of binding and interactions became weaker.

The preferred binding pose of each inhibitor was further analyzed to ascertain whether linkers play a biophysical role in interaction. Hydrogen bond interactions and the distance between N atoms of the two QAO were measured. The best sampled pose of each inhibitor is shown in Figures 7B–7G. Inhibitors 4S—12S displayed multiple orientations (Figures 7B and 7E) and tended to primarily occupy BS1 (see Figure 2B). Inhibitors 13S—19S (Figures 7C and 7F) displayed similar binding orientation. More specifically, one sulfated QAO monomer in these dimers displayed strong binding to BS1; however, the second monomer preferred to dock ~3–5 Å away from the BS2 (Figures 7C and 2B). Finally, inhibitors 20S and 21S with slightly longer linkers displayed a ~60° rotated binding orientation and significantly lower consistency (Figures 7D and 7G). These results support the IC50 results that the optimal number of intervening atoms is in the range of 8 to 10 atoms (Table 4).

To further assess the role of linkers, we also studied inhibitors 24S—26S containing triazole linkers. Each of the three inhibitors exhibited lower average GOLDScores in comparison to aliphatic linkers (Table 4). More importantly, the binding poses derived from multiple docking and scoring runs showed large inconsistency of binding. In fact, the RMSD of the top docked poses were greater than 12 Å, whereas the aliphatic linkers tended to display significantly high consistency (RMSD <3 Å). In combination, these results suggest that hFXIa prefers inhibitors with aliphatic linker of defined length.

Discussion

Human factor XIa (hFXIa) has attracted high attention lately because of multiple lines of evidence that indicate a strong possibility of devising a much safer anticoagulation therapy. Several reviews have been published touting the promise of targeting hFXIa.3–6 A 2015 study with a FXI-directed antisense oligonucleotide on 300 patients undergoing elective knee replacement gave sufficient evidence that this promise may hold true.8 This development gave new impetus to the discovery of active site inhibitors of hFXIa.20–30 Many of these studies, especially using animal models of thrombosis, continue to support the promise that targeting hFXIa is likely to yield reduced bleeding complications. In fact, two small molecules labeled EP-7041 and ONO-7684 are currently being studied in phase I clinical trials (NCT02914353 and NCT03919890, respectively; www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Unfortunately, none of the active site inhibitors that are being developed so far offer the possibility of intrinsic regulation such as partial antagonism. Active site inhibitors can either bind or not bind in the active site and induce either full inhibition (100%) or no inhibition (0%). Intermediate efficacies of inhibition, e.g., 30 – 60%, are not available. For this reason, we have pursued allosteric inhibitors of hFXIa to identify partial antagonists, or partial inhibitors, which may potentially lead to much safer anticoagulants. Our search has led to design of several allosteric hFXIa inhibitors including SPGG,17,18 SCI7 and sulfated benzofurans.19 Although some of these molecules, especially SCI, show that excellent inhibition potency and selectivity without much bleeding risk, scaffolds that offer partial antagonism remain to be discovered.

Rational design of partial antagonists is difficult. As of today, no specific principles have been put forward to discover partial antagonists. Majority of partial antagonists, especially of multi-domain cell surface receptors, have been derived from screening of natural products. In fact, partial antagonists of freely soluble enzymes are extremely difficult to find. We recently discovered that a sulfated benzofuran monomer bound in the heparin-binding site of human alpha-thrombin to induce ~50% inhibition.43,44 This molecule is the first partial allosteric inhibitor of a soluble enzyme identified to date and fueled the expectation that partial inhibitors of hFXIa should be possible to discover too.

This work stems from this expectation and employs the strategy of fragment-based design starting from a small molecule that is known to bind in the target binding site. Our earlier work had shown that monomeric sulfated QAO binds in heparin-binding site of hFXIa.16 Here we utilized molecular modeling to assess whether the heparin-binding site of hFXIa can accommodate more than one small sulfated fragments. We found that 2S, the monosulfated QAO fragment, is likely to bind in two unique sub-sites that are separated by ~10 Å, which is particularly amenable for fragment-based drug design. Thus, an optimal inhibitor should be possible to discover by linking the two monosulfated QAO fragments.

To a large extent, this work supports the expectation originating from fragment-based design strategy. Synthesis, enzyme activity assays, enzyme kinetics and biophysical studies of more than two dozen sulfated QAOs show that unique dimeric sulfated QAOs display more than 40-fold increase in potency over the monomeric fragment, bind preferentially with basic residues of the heparin-binding site present in catalytic domain, and induce co-operative disruption of the active site.

An extremely interesting result is the increase in inhibition potency as the length of the linker increases to 9 intervening atoms (i.e., 4 through 11). A priori, common principles of medicinal chemistry state that longer alkyl chains should enhance flexibility of the molecule, which should theoretically reduce affinity for protein targets. Yet, an exactly opposite behavior is observed here. The reason appears to be based on the mode of binding suggested by computational studies (Figure 2). These indicate that the orientation of the two monomeric sulfated QAOs in the two sub-sites is not face-to-face, which necessitates a round-about, flexible linker, thereby requiring 9 intervening atoms. In fact, molecular modeling studies show a preference for this linker length (Figure 7), while not completely ruling out longer linkers. Yet, the potencies of homodimeric sulfated QAOs (i.e., 20S and 21S, Table 1) start to decrease as linker length increases to 10 and 11 atoms. This suggests enhanced flexibility of the linker is likely to be detrimental. The FXIa inhibition potency of the best molecule discovered in this study, i.e., 19S, is reasonable (IC50 ~8 μM). Although not attractive for in-depth animal model studies, it would be worth the effort to study anti-thrombotic as well as bleeding consequences of this scaffold so as to direct future design efforts.

These fundamental results lead to the concept that better agents could be discovered by replacing part of the homodimer with a fragment that binds in a more favorable, direct, face-to-face orientation. A key conclusion here is that alternative fragment(s) of QAOs should be designed/discovered. One such fragment is the sulfated flavonoid scaffold, which could be thought of as a polysulfated version of the monosulfated QAO scaffold. In fact, we had evaluated this scaffold earlier for hFXIa. However, the extent of studies was restricted to linker lengths of 4 – 8 atoms.16

To assess whether the higher sulfated flavonoid fragment coupled with longer linkers may engineer higher potency, we compared homodimers 24S—29S with heterodimers 33S—36S. Unfortunately, none of the agents were found to be better than the aliphatic homodimers. This was a little surprising. Yet, the results convey the value of aliphatic linkers, while also perhaps suggesting that the triazole-based linker introduces unfavorable interactions and/or limited flexibility, thereby reducing potency. Our molecular modeling studies also support these conclusions (Table 4). A key conclusion from these results is that sulfated heterodimers with aliphatic linkers of 8 – 10 intervening atoms may yield agents with IC50s lower than 10 μM.

Finally, the efficacy of each inhibitor studied in this work was >90% (Table 1). Alternatively, no partial allosteric inhibitor was discovered. Yet, the results convincingly support the rationale that fragment-based strategy could rapidly lead to significant enhancement in inhibition potency. As noted earlier by us in the discovery of the sole partial allosteric inhibitor of human alpha-thrombin,43,44 we predict that screening a much larger library of such agents is necessary to identify the first partial inhibitor of hFXIa.

Experimental Methods

Molecular Modeling Studies—

The coordinates for the activated catalytic domain of hfXIa were obtained from the protein data bank (PDB ID: 1ZOM).12 Molecular modeling was performed using Tripos Sybyl-X v2.1 (Tripos Associates, St. Louis, MO), as described in our earlier publications on studies of non-saccharide glycosaminoglycan mimetics.35–37 Inhibitors 2S, 4S—21S and 24S—26S were docked in the catalytic domain of hFXIa using GOLD.35 The first step of fragment-based design utilized a region of 20 Å around each of Lys63, Lys107, Lys127, Arg147, Lys125, Arg185 and Lys202 (chymotrypsinogen numbering system) residues as the site of binding (Figure 2). For each site, 1000 genetic algorithm runs were employed. Each resulting pose was scored and best two poses with highest GOLDScores were retained. Then, triplicate docking runs were employed to assess consistency of binding, which equates to selectivity of recognition. The six docked poses per site were analyzed for RMSD (root mean square deviation) using in-house Sybyl script and the site with lowest RMSD value was selected as the preferred site of binding. To assess the aliphatic dimers with variable linker lengths, a similar docking and scoring strategy was followed except for few differences. The binding site was defined as an area of 28 Å around the BS1 and BS2, two loci obtained from sulfated QAO monomer binding studies. Although the number of genetic algorithm runs for each molecule remained the same, we retained all 1000 poses for analysis of preferred orientation of the linker and two monomer fragments.

Chemicals, Reagents and Analytical Chemistry—

Anhydrous CH2Cl2, THF, CH3CN, DMF, DMA, acetone and other solvents were reagent grade and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI) or Fisher (Pittsburgh, PA). Analytical TLC was performed using UNIPLATE™ silica gel GHLF 250 μm pre-coated plates (ANALTECH, Newark, DE). Column chromatography was performed using silica gel (200–400 mesh, 60 Å) from Sigma-Aldrich. Chemical reactions sensitive to air or moisture were carried out under nitrogen atmosphere in oven-dried glassware. Reagent solutions, unless otherwise noted, were handled under a nitrogen atmosphere using syringe techniques. Flash chromatography was performed using Teledyne ISCO (Lincoln, NE) Combiflash RF system and disposable normal silica cartridges of 30–50 μ particle size, 230–400 mesh size and 60 Å pore size. The flow rate of the mobile phase was in the range of 18 to 35 ml/min and mobile phase gradients of ethyl acetate/hexanes and CH2Cl2/CH3OH were used to elute compounds.

Proteins and Chromogenic Substrates—

Human plasma proteases including thrombin, FXa, FIXa, and FXIa were obtained from Haematologic Technologies (Essex Junction, VT). Active site-labeled hFXIa, i.e., FXIa-DEGR, was also obtained from Haematologic Technologies. Bovine α-chymotrypsin and bovine trypsin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Stock solutions of FXIa, thrombin, trypsin, FXIa-DEGR and chymotrypsin were prepared in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% PEG8000 and 0.02% Tween80. Stock solutions of FXa were prepared in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 100 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 0.1% PEG8000 and 0.02% Tween80. Chromogenic substrates, Spectrozyme TH (H-D-hexahydrotyrosol-Ala-Arg-p-nitroanilide), Spectrozyme FXa (methoxycarbonyl-D-cyclohexylglycyl-Gly-Arg-p-nitroanilide), and Spectrozyme CTY were from American Diagnostica (Greenwich, CT). FXIa chromogenic substrate S-2366 (H-D-Val-Leu-Arg-p-nitroanilide.2HCl) and trypsin substrate S-2222 (benzyl-Ile-Glu(–OH and –OCH3)-Gly-Arg-p-nitroanilide.HCl) were from Diapharma (West Chester, OH). Pooled normal human plasma was from Valley Biomedical (Winchester, VA). Activated partial thromboplastin time reagent containing ellagic acid, thromboplastin-D, and 25 mM CaCl2 were from Fisher Diagnostics (Middletown, VA). Precast gels (4 – 20% gradient) were from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). Recombinant human FXIa proteins, i.e., FXIaWT, FXIaCD, FXIaA3 and FXIaCD&A3, were a gift from Professor David Gailani from the Vanderbilt University.

Chemical Characterization of Compounds—

1H and 13C NMR were recorded using Bruker 400 MHz spectrometer in either CDCl3, CD3OD, acetone-d6, DMSO-D6 or D2O. Signals, in parts per million (ppm), were relative either to the internal standard or the residual peak of the solvent. NMR data are being reported as chemical shift (ppm), multiplicity of signal (s=singlet, d=doublet, t=triplet, q=quartet, dd=doublet of doublet, m=multiplet), coupling constants (Hz), and integration. ESI-MS were recorded using Waters Acquity TQD MS spectrometer in either positive or negative ion mode. Samples were dissolved in methanol and infused at a rate of 20 μL/min.

General procedure for synthesis of acetyl protected QAOs—

The QAO core structure was synthesized using a condensation reaction between anthranilamide and suitably substituted benzaldehyde in presence of sodium hydrogen sulfite and catalytic amounts of p-toluenesulfonic acid, as previously described.16 The free hydroxyl group(s) were acetylated in dichloromethane in the presence of N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) (2.0 equiv per hydroxyl group) and acetic anhydride (1.0 equiv per hydroxyl group), as described earlier.16

General procedure for dimerization of QAO monomers—

K2CO3 (2.5 eqv.) was added to solution of 1 – 3 in DMF under stirring (Scheme 1), which was followed by addition and agitation of an appropriate aryl/alkyl dibromide (0.5 eqv.) for 12 h. Following completion of reaction, confirmed by TLC, the mixture was acidified with water and extracted with ethyl acetate. The products were purified using flash chromatography on silica gel (10 – 50% ethyl acetate in hexanes) in 70 – 80% yield.

General procedure for deprotection of acetylated QAO dimers—

Acetylated dimers were first solubilized in THF and exposed to LiOH.H2O (4 eqv.) under vigorous stirring at room temperature for 4 – 6 h. The reaction mixture was extracted using ethyl acetate and product purified using flash chromatography on silica gel (20 – 70% ethyl acetate in hexanes) to give the deacetylated QAO dimers 7—21 in 70 – 80% yields.

General procedure for synthesis of sulfated QAOs—

Sulfation of phenolic precursors was achieved using microwave assisted chemical sulfation, as described earlier.16,39,40 Briefly, to a stirred solution of the appropriate polyphenol in an. CH3CN (1–5 mL) at room temperature, Et3N (10 eqv. per –OH group) and Me3N:SO3 complex (6 eqv. per –OH group) was added. The reaction vessel was sealed and micro-waved at 50 W (CEM Discover, Cary, NC) for 30 min at 90 °C. The reaction mixture was cooled and transferred to a round bottom flask, volume reduced as much as possible, and then directly loaded on to a flash chromatography column for purification using dichloromethane and methanol solvent system (5–20%) to obtain the quaternary amine conjugated sulfated QAOs. Flash chromatography when performed in this manner helps remove inorganics and aids purification. For sodium exchange, the samples were loaded onto a SP Sephadex C-25 column and lyophilized to obtain a white powder. Spectral characteristics of all the sulfated compounds 2S, 4S—21S, 24S—29S and 33S—36S are as follows.

(2S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 12.44 (s, 1H, NH), 8.15–8.13 (m, 3H, ArH), 7.85 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.74 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.52–7.48 (m, 1H, ArH), 7.33 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H, ArH). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): 156.4, 152.2, 134.4, 128.7, 127.3, 126.9, 126.1, 125.8, 120.7, 119.6. MS (ESI) calculated for C36H24N4Na2O10S2 [(M–Na)]−, m/z 317.02, found [(M–Na)]−, m/z 317.48.

(4S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): 8.37 (s, 2H, ArH), 8.3 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H, ArH), 8.22 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H, ArH), 8.01–7.94 (m, 4H, ArH), 7.7 (s, 4H, ArH), 7.67–7.63 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.51–7.4 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.37–7.36 (m, 2H, ArH), 5.83 (s, 4H, PhCH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): 165.9, 158.9, 157.6, 151.3, 138.7, 136.4, 134.3, 129.5, 128.3, 127.6, 127.2, 123.3, 119.1, 117.9, 114.6, 67.7. MS (ESI) calculated for C36H24N4Na2O10S2 [M]−, m/z 782.07, found [(M–2Na)]2-, m/z 367.89.

(5S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): 8.38 (s, 2H, ArH), 8.29 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, ArH), 8.18 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H, ArH), 8.02–7.95 (m, 5H, ArH), 7.68–7.60 (m, 4H, ArH), 7.53–7.44 (m, 3H, ArH), 7.37 (d, J = 7.56 Hz, 2H, ArH), 5.87 (s, 4H, PhCH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): 166.0, 158.7, 153.9, 151.2, 138.3, 136.7, 134.3, 128.9, 128.8, 127.7, 127.2, 123.3, 123.0, 120.4, 114.6, 67.9. MS (ESI) calculated for C36H24N4Na2O10S2 [M]−, m/z 782.07, found [(M–2Na)]2-, m/z 367.93.

(6S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): 8.5 (d, J = 8.65 Hz, 4H, ArH), 8.14 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.97–7.90 (m, 5H, ArH), 7.66–7.61 (m, 5H, ArH), 7.36 (d, J = 8.64, 4H, ArH), 5.87 (s, 4H, PhCH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): 165.9, 158.8, 156.1, 136.9, 134.2, 131.8, 129.0, 128.8, 127.8, 127.5, 127.3, 126.9, 123.2, 119.8, 114.3, 67.8. MS (ESI) calculated for C36H24N4Na2O10S2 [M]−, m/z 782.07, found [(M–2Na)]2-, m/z 367.93.

(7S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): 8.34 (s, 2H, ArH), 8.17 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 2H, ArH), 8.0–7.8 (m, 8H), 8.0–7.9 (m, 8H, ArH), 7.8–7.4 (m, 8H, ArH), 6.08 (s, 4H, PhCH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): 165.8, 158.6, 153.8, 151.1, 138.2, 135.2, 134.1, 130.4, 128.7, 127.5, 127.0, 123.2, 123.0, 120.4, 114.4, 66.6. MS (ESI) calculated for C36H24N4Na2O10S2 [M]−, m/z 782.07, found [(M–2Na)]2-, m/z 367.96.

(8S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): 8.3 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H, ArH), 7.93 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.8–7.7 (m, 6H, ArH), 7.43–7.41 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.32–7.27 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.21 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H, ArH), 5.98 (s, 4H, PhCH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): 165.7, 158.7, 156.0, 151.3, 135.2, 134.1, 131.7, 130.1, 128.9, 128.6, 127.4, 126.6, 122.9, 119.7, 114.1, 66.6. MS (ESI) calculated for C36H24N4Na2O10S2 [M]−, m/z 782.07, found [(M–2Na)]2-, m/z 367.89.

(9S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): 8.35–8.20 (m, 6H, ArH), 7.9 (s, 4H, ArH), 7.64 (s, 2H, ArH), 7.43 (m, 4H, ArH), 6.5 (s, 2H, C=CH), 5.4 (s, 4H, PhCH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): 165.8, 153.9, 151.2, 138.3, 134.3, 128.8, 127.6, 127.2, 123.2, 123.0, 120.4, 114.5, 66.3, 52.8. MS (ESI) calculated for C32H22N4Na2O10S2 [M]−, m/z 732.06, found [(M–2Na)]2-, m/z 342.91.

(10S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): 8.24 (s, 2H, ArH), 8.17 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H, ArH), 8.06 (d, J = 7.64 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.91–7.84 (m, 4H, ArH), 7.53–7.52 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.38–7.28 (m, 4H, ArH), 4.72 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 4H, NCH2), 2.04–1.97 (m, 4H, CH2), 1.8–1.73 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): 166.3, 158.8, 153.9, 151.1, 138.4, 134.1, 128.8, 127.6, 127.0, 123.2, 120.4, 114.6, 66.7, 27.9, 22.3. MS (ESI) calculated for C33H26N4Na2O10S2 [M]−, m/z 748.09, found [(M–2Na)]2-, m/z 350.94.

(11S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): 8.38 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H, ArH), 8.04 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.88 (m, 4H, ArH), 7.51–7.47 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.27 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H, ArH), 4.71 (s, 4H, NCH2), 2.01–1.97 (m, 4H, CH2), 1.77–1.74 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): 166.2, 158.9, 156.1, 151.3, 138.2, 134.0, 131.9, 128.9, 127.4, 126.6, 123.1, 119.8, 66.6, 27.9, 22.3. MS (ESI) calculated for C33H26N4Na2O10S2 [M]−, m/z 748.09, found [(M–2Na)]2-, m/z 351.00.

(12S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): 8.4 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 4H, ArH), 8.02 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.92–7.85 (m, 4H, ArH), 7.47 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.33 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 4H, ArH), 4.89 (s, 4H, OCH2), 4.12 (s, 4H, NCH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): 165.8, 153.9, 151.2, 138.3, 134.3, 128.8, 128.5, 127.6, 127.2, 123.2, 120.4, 114.5, 66.3, 52.8. MS (ESI) calculated for C32H24N4Na2O11S2 [M]−, m/z 750.07, found [(M–2Na)]2-, m/z 351.86.

(13S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): 8.3 (s, 2H, ArH), 8.25 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H, ArH), 8.14 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.98–7.93 (m, 4H, ArH), 7.58–7.37 (m, 6H, ArH), 4.76 (s, 4H, NCH2), 2.0 (s, 4H, CH2), 1.7 (s, 4H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): 166.3, 158.8, 153.9, 151.1, 138.4, 134.1, 128.8, 127.6, 127.0, 123.2, 120.4, 114.6, 66.8, 28.1, 25.4. MS (ESI) calculated for C34H28N4Na2O10S2 [M]−, m/z 762.10, found [(M–2Na)]2-, m/z 357.91.

(14S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): 8.4 (d, J = 8.8, 4H, ArH), 8.1 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.93–7.89 (m, 4H, ArH), 7.56–7.52 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.34 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H, ArH), 4.74 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 4H, NCH2), 2.0 (s, 4H, CH2), 1.7 (s, 4H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): 166.3, 158.8, 153.9, 151.1, 138.4, 134.1, 128.8, 127.6, 127.0, 123.2, 120.4, 114.6, 66.8, 28.1, 25.4. MS (ESI) calculated for C34H28N4Na2O10S2 [M]−, m/z 762.10, found [(M–2Na)]2-, m/z 357.94.

(15S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): 8.40 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 4H, ArH), 7.8 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.51–7.48 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.33–7.31 (m, 6H, ArH), 4.73 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 4H, NCH2), 3.8 (s, 6H, CH2), 2.0 (s, 4H, NCH2), 1.7 (s, 4H, NCH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): 165.3, 157.3, 156.9, 155.7, 146.8, 132.3, 129.3, 128.5, 125.4, 119.8, 114.9, 101.4, 66.6, 55.5, 28.1, 25.3. MS (ESI) calculated for C36H32N4Na2O10S2 [M]−, m/z 822.13, found [(M–2Na)]2-, m/z 387.96.

(16S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): 8.4 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 4H, ArH), 8.06 (d, J = 8.16 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.85–7.81 (m, 4H, ArH), 7.53–7.50 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.3 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 4H, ArH), 4.65 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 4H, NCH2), 3.0 (s, 4H, CH2), 1.16–0.97 (m, 6H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): 166.2, 158.9, 156.1, 151.3, 134.0, 131.9, 128.9, 127.4, 126.7, 123.2, 119.8, 114.4, 66.7, 52.78, 28.6, 28.2, 25.6. MS (ESI) calculated for C35H30N4Na2O10S2 [M]−, m/z 776.12, found [(M–2Na)]2-, m/z 364.98.

(17S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): 8.4 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H, ArH), 8.13 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.94–7.88 (m, 4H, ArH), 7.61–7.54 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.34 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H, ArH), 4.71 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 4H, NCH2), 2.09–1.89 (m, 4H, CH2), 1.56–1.47 (m, 4H, CH2), 1.08 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 4H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): 166.12, 158.9, 156.1, 151.2, 134.0, 131.9, 128.9, 127.4, 126.6, 123.1, 119.8, 114.3, 66.7, 28.6, 28.1, 25.5. MS (ESI) calculated for C36H32N4Na2O10S2 [(M–Na)]−, m/z 790.14, found [(M–2Na)]2-, m/z 371.96.

(18S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): 8.47–8.42 (m, 4H, ArH), 8.11 (d, J = 8.08 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.94–7.89 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.60–7.57 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.34 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.08 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H, ArH), 4.691 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 4H, NCH2), 3.84 (s, 3H, OCH3), 1.9–1.87 (m, 4H, CH2) 1.53–1.39 (m, 10H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): 166.1, 161.5, 158.8, 156.0, 151.2, 134.0, 131.9, 129.9, 129.6, 128.9, 127.4, 127.3, 126.6, 126.5, 123.1, 119.8, 114.3, 114.3, 113.8, 66.6, 66.6, 55.2, 28.7, 28.6, 28.1, 25.4. MS (ESI) calculated for C38H37N4NaO7S [M]−, m/z 716.23, found [(M–Na)]−, m/z 693.92.

(19S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): 8.4 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H, ArH), 8.13 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.95–7.89 (m, 4H, ArH), 7.62–7.58 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.34 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H, ArH), 4.71 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 4H, NCH2), 2.1–1.87 (m, 4H, CH2), 1.54 (s, 4H, CH2), 1.4 (s, 6H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): 166.2, 158.8, 156.1, 151.1, 134.0, 131.8, 129.9, 128.9, 127.3, 126.6, 123.1, 119.8, 115.3, 114.3, 66.7, 28.8, 28.7, 28.1, 25.5. MS (ESI) calculated for C37H34N4Na2O10S2 [M]−, m/z 804.15, found [(M–2Na)]2-, m/z 379.03.

(20S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): 8.4 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H, ArH), 8.14 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.96–7.90 (m, 4H, ArH), 7.63–7.60 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.4 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H, ArH), 4.71 (t, 6.5 Hz, 4H, NCH2), 1.93–1.86 (m, 4H, CH2), 1.54–1.49 (m, 4H, CH2), 1.4–1.34 (m, 8H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): 166.2, 159.1, 154.3, 134.1, 130.0, 128.9, 126.7, 126.5, 123.2, 119.8, 115.3, 114.1, 66.8, 28.7, 28.6, 28.1, 25.4. MS (ESI) calculated for C38H36N4Na2O10S2 [(M–Na)]−, m/z 818.17, found [(M–2Na)]2-, m/z 386.04.

(21S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): 8.4 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H, ArH), 8.13 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.94–7.88 (m, 4H, ArH), 7.6 (t, J = 1.6, 2H, ArH), 7.34 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H, ArH), 4.7 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 4H, NCH2), 1.93–1.87 (m, 4H, CH2), 1.53–1.48 (m, 4H, CH2), 1.38–1.31 (m, 10H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): 166.1, 158.8, 156.0, 151.2, 134.0, 131.9, 128.9, 127.4, 126.6, 123.1, 119.7, 114.3, 66.7, 28.8, 28.7, 28.1, 25.5. MS (ESI) calculated for C39H38N4Na2O10S2 [(M–Na)]−, m/z 832.18, found [(M–2Na)]2-, m/z 392.98.

(24S). 1H NMR (D2O, 400 MHz): 7.93 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.67–7.73 (m, 3H), 7.25–7.12 (m, 9H), 6.95 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 6.75–6.69 (m, 2H), 5.19 (s, 2H), 4.15 (bs, 2H), 3.58 (bs, 2H), 1.47 (s, 2H), 0.98 (s, 2H), 0.71–0.67 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): 165.7, 165.2, 158.7, 158.5, 153.6, 153.6, 150.1, 149.7, 142.8, 133.9, 133.7, 129.7, 129.6, 126.4, 125.8, 124.4, 121.1, 120.9, 113.6, 113.5, 66.7, 59.6, 50.3, 38.6, 29.3, 28.0, 27.6, 25.6, 25.1. MS (ESI) calculated for C38H33N7Na2O10S2 [M]−, m/z 857.15, found [(M-2Na)]2-, m/z 405.85

(25S). 1H NMR (D2O, 400 MHz): 7.94 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.78–7.73 (m, 3H), 7.25–7.01 (m, 9H), 7.02 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 6.78–6.74 (m, 2H), 5.22 (s, 2H), 4.12 (bs, 2H), 3.62 (bs, 2H), 1.44 (bs, 2H), 1.02 (s, 2H), 0.71–0.60 (m, 8H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): 165.8, 165.4, 158.7, 153.8, 153.7, 153.4, 150.1, 149.5, 142.9, 134.1, 133.7, 129.8, 129.7, 126.1, 125.5, 122.6, 121.2, 120.9, 113.7, 113.3, 66.8, 59.8, 50.3, 38.6, 29.4, 28.5, 28.2, 27.9, 25.8, 25.3. MS (ESI) calculated for C39H35N7Na2O10S2 [M]−, m/z 871.17, found [(M-2Na)]2-, m/z 412.47

(26S). 1H NMR (D2O, 400 MHz): 7.96 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.82–7.75 (m, 3H), 7.25–7.19 (m, 9H), 7.07 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 6.80–6.79 (m, 2H), 5.25 (s, 2H), 4.19 (bs, 2H), 3.70 (bs, 2H), 1.44 (bs, 2H), 1.1 (s, 2H), 0.70–0.56 (m, 10H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): 165.8, 165.4, 158.6, 154.0, 153.9, 153.8, 151.0, 149.8, 143.0, 134.8, 133.8, 129.6, 129.3, 126.8, 125.7, 123.7, 121.8, 120.9, 113.6, 113.3, 66.9, 60.0, 50.9, 38.6, 30.0, 28.5, 28.3, 27.8, 26.3, 25.5, 25.1. MS (ESI) calculated for C40H37N7Na2O10S2 [M]−, m/z 885.18, found [(M-2Na)]2-, m/z 419.96

(27S). 1H NMR (D2O, 400 MHz): 7.97 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 7.86–7.78 (m, 3H), 7.29–7.19 (m, 9H), 7.12 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.83–6.80 (m, 2H), 5.28 (s, 2H), 4.12 (bs, 2H), 3.73 (bs, 2H), 1.45 (bs, 2H), 1.12 (s, 2H), 0.74–0.53 (m, 12 H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): 165.8, 165.4, 158.6, 154.0, 153.9, 153.0, 150.1, 149.0, 142.8, 134.9, 133.9, 129.8, 129.3, 126.0, 125.0, 123.7, 121.1, 120.9, 113.8, 113.3, 66.9, 60.1, 50.2, 42.5, 29.6, 28.9, 28.5, 25.9, 25.6, 25.1, 24.7. MS (ESI) calculated for C41H39N7Na2O10S2 [M]−, m/z 899.20, found [(M-2Na)]2-, m/z 426.94

(28S). 1H NMR (D2O, 400 MHz): 7.98 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 7.85–7.77 (m, 3H), 7.31–7.23 (m, 9H), 7.15 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.78–6.72 (m, 2H), 5.39 (s, 2H), 4.18 (bs, 2H), 3.81 (bs, 2H), 1.48 (bs, 2H), 1.14 (s, 2H), 0.89–0.68 (m, 14H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): 165.8, 165.3, 158.7, 155.0, 154.1, 153.6, 150.1, 149.0, 143.7, 135.1, 134.0, 129.8, 129.1, 126.6, 125.3, 123.7, 121.0, 120.1, 113.8, 113.1, 66.7, 60.0, 50.2, 42.9, 29.8, 28.6, 28.3, 25.2, 25.1, 25.1, 24.8, 24.6. MS (ESI) calculated for C42H41N7Na2O10S2 [M]−, m/z 913.22, found [(M-2Na)]2-, m/z 433.53

(29S). 1H NMR (D2O, 400 MHz): 7.96 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.89–7.81 (m, 3H), 7.43–7.19 (m, 9H), 7.03 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.83–6.75 (m, 2H), 5.25 (s, 2H), 4.13 (bs, 2H), 3.84 (bs, 2H), 1.48 (bs, 2H), 1.25 (s, 2H), 0.88–0.65 (m, 16H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): 165.8, 165.3, 158.7, 155.0, 154.1, 153.7, 150.1, 149.0, 143.7, 135.1, 134.0, 129.7, 129.1, 126.6, 125.4, 123.7, 121.0, 120.1, 113.9, 113.1, 66.7, 60.0, 50.2, 42.9, 29.8, 28.6, 28.3, 25.2, 25.1, 25.1, 24.9, 24.6. MS (ESI) calculated for C43H43N7Na2O10S2 [M]−, m/z 927.23, found [(M-2Na)]2-, m/z 440.55

(33S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): 8.42 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 8.31–8.28 (m, 1H), 8.15–8.11 (m, 3H), 7.93–7.9 (m, 2H), 7.65–7.62 (m, 2H), 7.34 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.13–7.07 (m, 1H), 6.85–6.81 (m, 1H), 5.24 (s, 2H), 4.71 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 4.37 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 1.93–1.85 (m, 4H) 1.55–1.24 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): 169.0, 160.3, 157.9, 155.8, 154.1, 148.6, 143.7, 135.1, 132.0, 129.8, 128.8, 127.3, 124.3, 123.1, 119.0, 115.1, 114.1, 114.0, 113.9, 66.7, 52.8, 49.4, 29.2, 28.6, 28.3, 25.2, 25.1. MS (ESI) calculated for C39H30N5Na5O24S5 [(M-Na)]−, m/z 1203.94, found [(M-2Na)]2-, m/z 590.38

(34S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): 8.44 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 8.32–8.27 (m, 1H), 8.15–8.12 (m, 3H), 7.94–7.92 (m, 2H), 7.64–7.61 (m, 2H), 7.34 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.13–7.07 (m, 1H), 6.86–6.82 (m, 1H), 5.23 (s, 2 H), 4.71 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 4.38 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 1.93–1.85 (m, 4H) 1.54–1.23 (m, 8H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): 169.0, 160.2, 158.8, 156.0, 151.0, 148.5, 142.2, 134.1, 131.8, 129.9, 128.9, 127.3, 126.7, 124.3, 123.2, 119.8, 115.3, 114.3, 114.1, 66.8, 52.8, 49.4, 29.7, 28.5, 28.2, 28.1, 25.8, 25.4. MS (ESI) calculated for C40H32N5Na5O24S5 [(M-Na)]−, m/z 1217.96, found [(M-2Na)]2-, m/z 597.39

(35S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): 8.45 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 8.30–8.27 (m, 1H), 8.16–8.13 (m, 3H), 7.94–7.92 (m, 2H), 7.63–7.61 (m, 2H), 7.34 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.13–7.07 (m, 1H), 6.84 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 5.23 (s, 2H), 4.71 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 4.37 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 1.93–1.84 (m, 4H) 1.54–1.28 (m, 10H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): 169.2, 158.8, 156.1, 155.0, 154.1, 153.3, 150.1, 148.5, 143.7, 134.1, 134.3, 129.9, 128.9, 127.3, 124.2, 123.2, 119.8, 115.3, 114.3, 66.0, 52.7, 49.3, 29.7, 28.7, 28.2, 28.1, 25.8, 25.46, 25.1, 24.3, 24.8.MS (ESI) calculated for C41H34N5Na2O24S5 [(M-Na)]−, m/z 1231.98, found [(M-Na)]−, m/z 604.38

(36S). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): 8.44 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 8.30–8.27 (m, 1H), 8.17–8.13 (m, H), 7.93–7.91 (m, 2H), 7.62–7.6 (m, 2H), 7.32 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.13–7.07 (m, 1H), 6.85 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 5.23 (s, 2H), 4.72 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 4.38 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 1.94–1.84 (m, 4H) 1.54–1.28 (m, 12H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): 169.2, 160.1, 158.2, 156.0, 151.0, 148.5, 142.2, 134.1, 131.7, 129.8, 128.6, 127.3, 126.7, 124.0, 123.2, 119.8, 115.2, 114.3, 114.1, 66.7, 52.1, 49.3, 29.7, 28.2, 28.3, 28.2, 25.1, 25.4, 24.1. MS (ESI) calculated for C42H36N5Na2O24S5 [(M-Na)]−, m/z 1246.00, found [(M-2Na)]2-, m/z 612.43

Direct inhibition of hFXIa by Sulfated QAOs—

A microplate reader-based chromogenic substrate hydrolysis assay was used to measure direct inhibition of hFXIa, as described earlier.16–19 Briefly, each well of a 96-well microplate carrying 85 μL of pH 7.4 buffer (50 mM Tris.HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% PEG8000 and 0.02% Tween80), 5 μL of a potential inhibitor (or reference solution), and 5 μL of hFXIa (0.765 nM final concentration in the well) was incubated at 37 °C for 10 min, after which S2366 (5 μL, 345 μM final concentration in the well) was added and the residual hFXIa activity was measured from the initial rate of increase A405. The relative residual hFXIa activity was calculated from the initial rates in the presence and absence of the inhibitor. The dose–dependence of residual activity was analyzed using the standard logistic equation to obtain the potency (IC50) and efficacy (ΔY) of inhibition.

Direct inhibition of related serine proteases—

The inhibition of thrombin, FIXa, FXa, kallikrein, trypsin and chymotrypsin by sulfated QAOs was measured using appropriate chromogenic substrates, as reported in the literature.16–19 These assays were performed at 37 °C and pH 7.4, except for thrombin, which was performed at 25 °C and pH 7.4. The concentrations of enzymes and substrates in the wells were respectively, 6 nM and 50 μM (thrombin); 1.09 nM and 125 μM (hFXa); 20 nM and 200 μM (plasma kallikrein); 2.5 ng/ml and 80 μM (trypsin); 500 ng/ml and 240 μM (chymotrypsin); and 89 nM and 425 μM (hFIXa). The ratio of the proteolytic activity in the presence of sulfated QAO to that in its absence was used to calculate percent inhibition (%).

Michaelis–Menten Kinetics of Substrate Hydrolysis—

The initial rate of S2366 hydrolysis by hFXIa was obtained from the linear increase in A405 corresponding to less than 10% consumption of the substrate. The initial rate was measured at S2366 concentrations between 0.03 and 2 mM in the presence of fixed concentration of 19S in 50 mM Tris.HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% PEG8000 and 0.02% Tween80 at 37 °C. The data were analyzed using the standard hyperbolic Michaelis–Menten equation (VI = VMAX×[S]/(KM + [S])) to calculate KM and VMAX.

Affinity (KD) of sulfated QAOs binding to hFXIa—

Fluorescence experiments were performed using a QM4 spectrofluorometer (Photon Technology International, Birmingham, NJ) in 50 mM Tris.HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 150 mM NaCl and 0.1% PEG8000 at 37 °C. The KD of hFXIa–inhibitor complex was measured using the change in the fluorescence of the active site dansyl group as a function of inhibitor concentration. Titrations were performed by adding aliquots of sulfated QAOs to a fixed concentration of hFXIa–DEGR (250 nM) and monitoring the change in emission at 547 nm (λEX = 345 nm). The slit widths on the excitation and emission side were 1 mm each. The fluorescence change was fitted using the Hill equation 1 for ligand binding to obtain the dissociation constant (KD). In this equation, ΔF represents the change in fluorescence following addition of sulfated QAO (i.e., [I]) from the initial fluorescence (F0), while ΔFMAX represents the maximal change in fluorescence. Hill coefficient ‘n’ is a measure of the cooperativity of binding.

| (1) |

Analytical ultracentrifugation studies—

hFXIa was diluted to 0.2 mg/mL in 50 mM Tris.HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 150 mM NaCl and 0.1% PEG8000 at 20 °C. Samples (420 μL) of hFXIa alone and hFXIa-19S complex (100 μM), were run at 25,000 rpm overnight at 20 °C in a Beckman Coulter XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge. Absorbance (λ = 280 nm) and interference scans were recorded until the boundary moved to the bottom of the cell. The continuous distribution C(s) distribution analysis was performed using SEDFIT (https://sedfitsedphat.nibib.nih.gov).

Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

hFXIa and hFXIa in the presence of 19S (100 μM) were analyzed by native PAGE (4–20%) using Mini-PROTEAN® TGX™ from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). Laemmli sample buffer (10 μL, 2X concentration, Bio-Rad) was mixed with 10 μL of hFXIa or hFXIa-19S samples and directly loaded onto the gel without boiling. The gel was run at a constant 65 V and stained using 30% methanol, 10% acetic acid, 0.1% brilliant blue R solution for 20 min at room temperature. Following de-staining with 30% methanol and 10% acetic acid, an image of the gel was captured.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor David Gailani of Vanderbilt University for the gift of recombinant FXIa proteins (wild-type and heparin-binding site mutants). We also thank the computational resources made available to us through a grant from the National Center for Research Resources (S10 RR027411) to VCU. This work was supported in part by grants from the NIH including HL107152, HL090586 and HL128639 (URD).

Abbreviations

- AUC

analytical ultracentrifugation

- BS1

binding site 1

- BS2

binding site 2

- DEGR-FXIa

Dansyl EGR-labeled FXIa

- GAG

glycosaminoglycan

- HBS

Heparin-binding site

- PMSF

Phenyl methylsulfonyl fluoride

- QAO

quinazolinone

- SPGG

sulfated pentagalloyl glucoside

- UFH

unfractionated heparin

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Mulloy B, Hogwood J, Gray E, Lever R, Page CP, Pharmacology of heparin and related drugs. Pharmacol. Rev 68 (2016) 76–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy JH, Douketis J, Weitz JI, Reversal agents for non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants. Nat. Rev. Cardiol 15 (2018) 273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan NC, Weitz JI, Antithrombotic agents: new directions in antithrombotic therapy. Circ. Res 124 (2019) 426–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gailani D, Gruber A, Factor XI as a therapeutic target. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 36 (2016) 1316–1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quan ML, Pinto DJP, Smallheer JM, Ewing WR, Rossi KA, Luettgen JM, Seiffert DA, Wexler RR, Factor XIa inhibitors as new anticoagulants. J. Med. Chem 61 (2018) 7425–7447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Horani RA, Afosah DK, Recent advances in the discovery and development of factor XI/XIa inhibitors. Med. Res. Rev 38 (2018) 1974–2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Horani RA, Abdelfadiel EI, Afosah DK, Morla S, Sistla JC, Mohammed B, Martin EJ, Sakagami M, Brophy DF, Desai UR, A synthetic heparin mimetic that allosterically inhibits factor XIa and reduces thrombosis in vivo without enhanced risk of bleeding. J. Thromb. Haemost 17 (2019) 2110–2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bueller HR, Bethune C, Bhanot S, Gailani D, Monia BP, Raskob GE, Segers A, Verhamme P, Weitz JI, Factor XI antisense oligonucleotide for prevention of venous thrombosis. N. Eng. J. Med 372 (2015) 232–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crosby JR, Marzec U, Revenko AS, Zhao CG, Gao DC, Matafonov A, Gailani D, MacLeod AR, Tucker EI, Gruber A, Hanson SR, Monia BP, Antithrombotic effect of antisense factor XI oligonucleotide treatment in primates. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 33 (2013) 1670–1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schumacher WA, Seiler SE, Steinbacher TE, Stewart AB, Bostwick JS, Hartl KS, Liu EC, Ogletree ML, Antithrombotic and hemostatic effects of a small molecule factor XIa inhibitor in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol 570 (2007) 167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gailani D, Smith SB, Structural and functional features of factor XI. J. Thromb. Haemost 7 Suppl 1 (2009) 75–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papagrigoriou E, McEwan PA, Walsh PN, Emsley J, Crystal structure of the factor XI zymogen reveals a pathway for transactivation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 13 (2006) 557–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geng Y, Verhamme IM, Smith SA, Cheng Q, Sun M, Sheehan JP, Morrissey JH, Gailani D, Factor XI anion-binding sites are required for productive interactions with polyphosphate. J. Thromb. Haemost 11 (2013) 2020–2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho DH, Badellino K, Baglia FA, Walsh PN, A binding site for heparin in the apple 3 domain of factor XI. J. Biol. Chem 273 (1998) 16382–16390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao M, Abdel-Razek T, Sun MF, Gailani D, Characterization of a heparin binding site on the heavy chain of factor XI. J. Biol. Chem 273 (1998) 31153–31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karuturi R, Al-Horani RA, Mehta SC, Gailani D, Desai UR, Discovery of allosteric modulators of factor XIa by targeting hydrophobic domains adjacent to its heparin-binding site. J. Med. Chem 56 (2013) 2415–2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Horani RA, Ponnusamy P, Mehta AY, Gailani D, Desai UR, Sulfated pentagalloylglucoside is a potent, allosteric, and selective inhibitor of factor XIa. J. Med. Chem 56 (2013) 867–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Horani RA, Desai UR, Designing allosteric inhibitors of factor XIa. Lessons from the interactions of sulfated pentagalloylglucopyranosides. J. Med. Chem 57 (2014) 4805–4818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Argade MD, Mehta AY, Sarkar A, Desai UR, Allosteric inhibition of human factor XIa: discovery of monosulfated benzofurans as a class of promising inhibitors. J. Med. Chem 57 (2014) 3559–3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fang TN, Corte JR, Gilligan PJ, Jeon Y, Osuna H, Rossi KA, Myers JE, Sheriff S, Lou Z, Zheng JJ, Orally bioavailable amine-linked macrocyclic inhibitors of factor XIa. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 30 (2020) in press. DOI: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.126949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corte JR, Pinto DJP, Fang TA, Osuna H, Yang W, Wang YF, Lai A, Clark CG, Sun JH, Rampulla R, Mathur A, Kaspady M, Neithnadka PR, Li YXC, Rossi KA, Myers JE, Sheriff S, Lou Z, Harper TW, Huang C, Zheng JJ, Bozarth JM, Wu YM, Wong PC, Crain EJ, Seiffert DA, Luettgen JM, Lam PYS, Wexler RR, Ewing WR, Potent, orally bioavailable, and efficacious macrocyclic inhibitors of factor XIa. Discovery of pyridine-based macrocycles possessing phenylazole carboxamide P1 groups. J. Med. Chem 63 (2020) 784–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clark CG, Rossi KA, Corte JR, Fang TA, Smallheer JM, De Lucca I, Nirschl DS, Orwat MJ, Pinto DJP, Hu ZL, Wang YF, Yang W, Jeon Y, Ewing WR, Myers JE, Sheriff S, Lou Z, Bozarth JM, Wu YM, Rendina A, Harper T, Zheng J, Xin BM, Xiang Q, Luettgen JM, Seiffert DA, Wexler RR, Lam PYS, Structure based design of macrocyclic factor XIa inhibitors: Discovery of cyclic P1 linker moieties with improved oral bioavailability. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 29 (2019) DOI: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei QC; Zheng ZC; Zhang SJ; Zheng XM; Meng FC; Yuan J; Xu YN; Huang CJ Fragment-based lead generation of 5-phenyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide derivatives as leads for potent factor XIa inhibitors. Molecules. (2018) 23, DOI 10.3390/molecules23082002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu Z, Wang C, Han W, Rossi KA, Bozarth JM, Wu Y, Sheriff S, Myers JE Jr., Luettgen JM, Seiffert DA, Wexler RR, Quan ML, Pyridazine and pyridazinone derivatives as potent and selective factor XIa inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 28 (2018) 987–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinto DJP, Orwat MJ, Smith LM, Quan ML, Lam PYZ, Rossi KA, Apedo A, Bozarth JM, Wu YM, Zheng JJ, Xin BM, Toussaint N, Stetsko P, Gudmundsson O, Maxwell B, Crain EJ, Wong PC, Lou Z, Harper TW, Chacko SA, Myers JE, Sheriff S, Zhang HP, Hou XP, Mathur A, Seiffert DA, Wexler RR, Luettgen JM, Ewing WR, Discovery of a parenteral small molecule coagulation factor Xla inhibitor clinical candidate (BMS-962212). J. Med. Chem 60 (2017) 9703–9723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang CL, Corte JR, Rossi KA, Bozarth JM, Wu YM, Sheriff S, Myers JE, Luettgen JM, Seiffert DA, R Wexler R, Quan ML, Macrocyclic factor XIa inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 27 (2017) 4056–4060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corte JR, Yang W, Fang TA, Wang YF, Osuna H, Lai A, Ewing WR, Rossi KA, Myers JE, Sheriff S, Lou Z, Zheng JJ, Harper TW, Bozarth JM, Wu YM, Luettgen JM, Seiffert DA, Quan ML, Wexler RR, Lam PYS, Macrocyclic inhibitors of Factor XIa: Discovery of alkyl-substituted macrocyclic amide linkers with improved potency. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 27 (2017) 3833–3839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corte JR, Fang TA, Osuna H, Pinto DJP, Rossi KA, Myers JE, Sheriff S, Lou Z, Zheng JJ, Harper TW, Bozarth JM, Wu YM, Luettgen JM, Seiffert DA, Decicco CP, Wexler RR, Quan MML, Structure-based design of macrocyclic factor XIa inhibitors: Discovery of the macrocyclic amide linker. J. Med. Chem 60 (2017) 1060–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corte JR, Fang T, Pinto DJP, Orwat MJ, Rendina AR, Luettgen JM, Rossi KA, Wei AZ, Ramamurthy V, Myers JE, Sheriff S, Narayanan R, Harper TW, Zheng JJ, Li YX, Seiffert DA, Wexler RR, Quan MML, Orally bioavailable pyridine and pyrimidine-based Factor XIa inhibitors: Discovery of the methyl N-phenyl carbamate P2 prime group. Bioorg. Med. Chem 24 (2016) 2257–2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith II LM, Orwat MJ, Hu Z, Han W, Wang C, Rossi KA, Gilligan PJ, Pabbisetty KB, Osuna H, Corte JR, Rendina AR, Luettgen JM, Wong PC, Narayanan R, Harper TW, Bozarth JM, Crain EJ, Wei A, Ramamurthy V, Morin PE, Xin B, Zheng J, Seiffert DA, Quan ML, Lam PYS, Wexler RR, Pinto DJP, Novel phenylalanine derived diamides as Factor XIa inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 26 (2016) 472–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buchanan MS, Carroll AR, Wessling D, Jobling M, Avery VM, Davis RA, Feng YJ, Xue YF, Oster L, Fex T, Deinum J, Hooper JNA, Quinn RJ, Clavatadine A, a natural product with selective recognition and irreversible inhibition of factor XIa. J. Med. Chem 51 (2008) 3583–3587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Horani RA , Factor XI(a) inhibitors for thrombosis: an updated patent review (2016-present). Exp. Opin. Ther. Patents 30 (2020) 39–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-Horani RA, Desai UR, Factor XIa inhibitors: A review of the patent literature. Exp. Opin. Ther. Patents 26 (2016) 323–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mehta AY, Mohammed BM, Martin EJ, Brophy DF, Gailani D, Desai UR, Allosterism-based simultaneous, dual anticoagulant and antiplatelet action: allosteric inhibitor targeting the glycoprotein Ibα-binding and heparin-binding site of thrombin. J Thromb Haemost. 14 (2016) 828–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Afosah DK, Al-Horani RA, NV. Sankaranarayanan, U.R. Desai, Potent, selective, allosteric inhibition of human plasmin by sulfated non-saccharide glycosaminoglycan mimetics. J. Med. Chem 60 (2017) 641–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.NV Sankaranarayanan UR Desai. Toward a robust computational screening strategy for identifying glycosaminoglycan sequences that display high specificity for target proteins. Glycobiology 24 (2014) 1323–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sidhu PS, Abdel Aziz MH, Sarkar A, Mehta AY, Zhou Q, Desai UR, Designing allosteric regulators of thrombin. Exosite 2 features multiple subsites that can be targeted by sulfated small molecules for inducing inhibition. J. Med. Chem 56 (2013) 5059–5070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abdel Aziz MH, Sidhu PS, Liang A, Kim JY, Mosier PD, Zhou Q, Farrell DH, Desai UR, Designing allosteric regulators of thrombin. Monosulfated benzofuran dimers selectively interact with Arg173 of exosite 2 to induce inhibition. J. Med. Chem 55 (2012) 6888–6897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Horani RA, Desai UR, Chemical sulfation of small molecules - advances and challenges. Tetrahedron 66 (2010) 2907–2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.A Raghuraman M Riaz, M. Hindle, U.R. Desai, Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted synthesis of highly sulfated organic scaffolds. Tetrahedron Lett. 48 (2007) 6754–6758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaushik CP, Sangwan J, Luxmi R, Kumar K, Pahwa A, Synthetic routes for 1,4-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazoles: A review. Curr. Org. Chem 23 (2019) 860–900. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gailani D, Geng Y, Verhamme I, Sun MF, Bajaj SP, Messer A, Emsley J, The mechanism underlying activation of factor IX by factor XIa. Thromb. Res 133 (2014) S48–S51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Afosah DK, Verespy S 3rd, Al-Horani RA, Boothello RS, Karuturi R, Desai UR, A small group of sulfated benzofurans induces steady-state submaximal inhibition of thrombin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 28 (2018) 1101–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verespy S 3rd, Mehta AY, Afosah D, Al-Horani RA, Desai UR, Allosteric partial inhibition of monomeric proteases. Sulfated coumarins induce regulation, not just inhibition, of thrombin. Sci. Rep 6 (2016) 24043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.