Abstract

The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) recommends a blood pressure (BP) goal of <140/90 mm Hg in patients with hypertension and <130/80 mm Hg in those with diabetes or chronic kidney disease. Achievement of BP goals is associated with significant benefits in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Although evidence suggests these goals are attainable, only about one third of patients are meeting them. There is a significant gap between treatment guideline recommendations and their implementation in clinical practice. Many clinicians appear satisfied with modest BP reductions and do not make the necessary treatment adjustments to achieve BP goals. Patient nonadherence is another important reason for lack of BP control. For the success of clinical trials to be reproduced in clinical practice, clinicians must recognize the importance of treating BP to goal, emphasize to patients the need to adhere to treatments, and provide persistent, goal‐targeted therapy.

Hypertension, defined as a systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 mm Hg or a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mm Hg, is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Hypertension was listed as the primary or contributing cause of cardiovascular death in approximately 261,000 cases in the United States in 2002 1 and is recognized as one of the major treatable conditions contributing to disease burden worldwide. 2

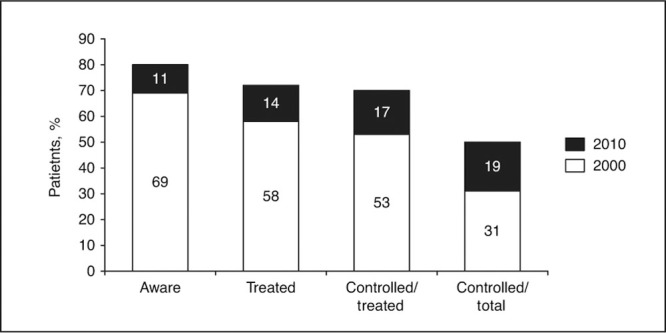

Considering the well established risks of high BP, the recent report that the prevalence of hypertension in the United States has increased by 30%, from 50 million people in the 1988‐1994 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to 65 million people in the 1999‐2000 survey, is a matter of growing concern. 3 This increase is probably associated primarily with increased obesity and the aging of the population. 3 Lowering blood pressure (BP) in hypertensive patients is associated with a 35%–40% reduction in stroke, a 20%–25% reduction in myocardial infarction, and a >50% reduction in heart failure. 4 Despite the proven clinical benefits of lowering BP, only approximately 34% of hypertensives in the United States are achieving the recommended BP goal of <140/90 mm Hg (Table I). 5 , 6 Although hypertension goal attainment rates have increased by 6% since 1988–1991, they remain far from the Healthy People 2010 7 goal of 50%, which was also the failed 2000 goal. To achieve these goals, we must raise our detection rate from 69% to 80% and our treatment rate from 58% to more than 70% (Figure 1). 8

Table I.

Awareness, Treatment, and Control* of Hypertension in the United States Between 1988 and 2000

| Weighted % of Hypertension Population | 1988–1991 | 1991–1994 | 1999–2000 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness | 73 | 68 | 70 |

| Treatment | 55 | 54 | 59 |

| Control* | 29 | 27 | 34 |

| *Blood pressure <140/90 mm Hg. Adapted with permission from the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. | |||

Figure 1.

Proportions of patients with hypertension diagnosis, treatment, and control in 2000 and the incremental increases in these proportions required by 2010 to meet the Healthy People 2010 goal of controlling hypertension in 50% of affected patients.

Despite less‐than‐ideal control rates, cases of malignant or accelerated hypertension have decreased dramatically due to earlier treatment. 9 Cardiovascular event rates have decreased and could decrease even further if more patients were treated and BP goals were achieved.

This paper reviews the importance of treating hypertension effectively and persistently to achieve recommended BP goals. In addition, factors that prevent hypertensive patients from achieving BP goals will be examined, as will the ability to achieve BP goals with currently available antihypertensive medications.

MEASURING ANTIHYPERTENSIVE EFFECTS

The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) 6 states that the main aim of antihypertensive therapy is to reduce morbidity and mortality by maintaining BP at target levels. The BP goal is <140/90 mm Hg for most patients with hypertension, and <130/80 mm Hg for patients with comorbid diabetes or chronic kidney disease. While some patients can achieve these goals with monotherapy, combination therapy will be required for the majority of patients. 10 In patients with stage 2 hypertension (SBP ≥160 mm Hg or DBP ≥100 mm Hg), JNC 7 recommends that treatment be started with at least 2 antihypertensive agents, usually a thiazide‐type diuretic and another agent with a complementary mechanism of action. 6

Until recently, the proportion of patients attaining recommended BP goals was rarely reported in clinical trials. Instead, mean reductions in BP levels were the primary end point of interest. In comparative studies, similar mean reductions in BP do not always translate into similar rates of achievement of goal BP. For example, in a recent study using 24‐hour ambulatory BP monitoring, patients receiving a calcium channel blocker (CCB) or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) achieved a similar mean reduction in BP, but a significantly higher proportion of patients in the ARB group achieved recommended BP goals. 11

Alternatively, responder rates based solely on DBP levels have been commonly used as a measure of treatment success. These do not, however, reflect the percentage of patients achieving both SBP and DBP goals. The importance of lowering SBP was not widely recognized until the publication of the results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) 12 and Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst‐Eur) study. 13 As observational studies have shown that SBP is a better indicator of cardiovascular risk than DBP, especially in patients older than 50 years, controlling SBP is of great importance in light of the aging population in the United States.

THE IMPORTANCE OF BP GOALS IN HYPERTENSION

The Veterans Administration Cooperative Study 14 , 15 conducted in the 1960s was the first to show that large reductions in BP to near the currently recognized BP goal were associated with significant reductions in cardiovascular events. More recently, a study of more than 30,000 subjects followed for 8–12 years confirmed that uncontrolled BP was the major determinant of increased mortality among treated hypertensive patients. 16 These results suggest that we could substantially lower the risk of cardiovascular disease associated with hypertension by achieving BP goals.

The cardiovascular benefits of treating to BP goal were recently demonstrated in the Brisighella Heart Study. 17 Hypertensive patients whose BP was <140/90 mm Hg had a significantly lower risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality compared with those whose BP was ≥140/90 mm Hg after adjustment for major cardiovascular risk factors (age, sex, smoking, diabetes, and cholesterol levels) in men (relative risk, 2.3; P<.001) and women (relative risk, 1.4; P<.05).

In the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS), 18 treating hypertensive diabetic patients to a BP goal of <150/85 mm Hg (mean achieved BP, 144/82 mm Hg) was associated with a 24% reduction in the risk of diabetes‐related end points (P<.005) compared with patients treated to a less stringent goal of <180/105 mm Hg (mean achieved BP, 154/87 mm Hg). This 10/5 mm Hg lower BP was associated with a 32% reduction in mortality (P<.02).

As evidenced by studies like UKPDS, benefits can be achieved even with BP reductions that do not achieve goal; however, it is likely that the greater the reductions in BP, the greater the cardiovascular benefits. 19

BP GOAL ACHIEVEMENT RATES

The 1999–2000 NHANES study demonstrated that although 70% of hypertensive patients in the United States were aware they had hypertension, and 59% were receiving treatment, hypertension was controlled (BP <140/90 mm Hg) in only 34% of all patients, or 53%–58% of treated patients (Table I). 5 Patients with comorbid diabetes have even lower BP goal attainment rates, because of the more stringent BP target of < 130/80 mm Hg, but also because it is more difficult to lower BP in diabetic patients.

In the Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT), 10 diabetics were 14% less likely than nondiabetics (P<.05) to achieve a BP goal <140/90 mm Hg. A retrospective review of 977 hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes treated in clinical practice showed that only 14% of patients achieved the BP goal of <130/80 mm Hg. 20 Although this may reflect in part the investigators' applying a lower BP goal, based on more recent recommendations than were standard during the observation period, it demonstrates the gap between recent control rates and the currently recommended BP goal in this population.

Poor BP goal attainment is not unique to the United States. A survey of BP control rates in Italy, Spain, France, the United Kingdom, and Germany revealed that BP goals were reached in only 37% of treated hypertensive patients. 21 Interestingly, the doctors surveyed believed that target BP was reached in 76% of their patients, and 95% of the patients themselves believed their BP was well controlled.

Despite these findings, clinical trials have shown that, with persistent treatment, usually using a treatment algorithm, the recommended BP goal of <140/90 mm Hg can be achieved in 45%–72% of hypertensive patients (Table II). 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 Within the Veterans Affairs clinics system, BP goal attainment rates rose from 31% in the early 1990s to 46% in 2000 and 67% in 2004, 26 demonstrating that BP goal rates similar to what has been achieved in clinical trials can be achieved within large medical care systems with active patient follow‐up and management.

Table II.

Blood Pressure Goal Rates (<1 40/90 mm Hg)* in Hypertensive Patients Receiving Treatment

| Trial/Antihypertenive† | Follow‐Up,y | Patients at Goal, % |

|---|---|---|

| INVEST 22 | 2 | |

| Verapamil | 72 | |

| Atenolol | 71 | |

| CONVINCE 23 | Median, 3 | |

| Verapamil | 66 | |

| Atenolol | 66 | |

| ALLHAT 24 | 5 | |

| Chlorthalidone | 68 | |

| Amlodipine | 66 | |

| Lisinopril | 61 | |

| LIFE 25 | Mean, 4.8 | |

| Losartan | 48 | |

| Atenolol | 45 | |

| *Goal per the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7). 6 †All trials used multiple medications but therapy was based on the agent listed. INVEST indicates International Verapamil‐Trandolapril Study; CONVINCE, Controlled Onset Verapamil Investigation of Cardiovascular End Points; LIFE, Losartan Intervention For Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension Study; and ALLHAT is expanded in the text. | ||

WHAT IT TAKES

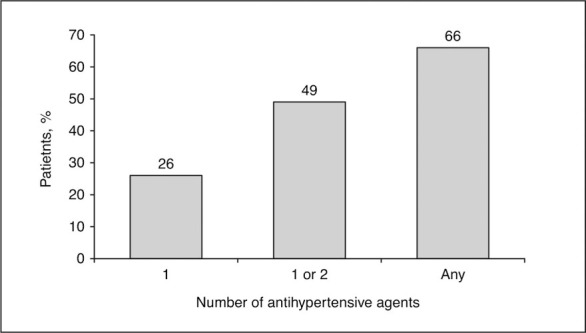

Treatment algorithms are usually required to achieve high BP goal rates. In the ALLHAT trial, 10 only 26% of study participants achieved the BP goal of <140/90 mm Hg with a single antihypertensive agent, and only 49% achieved goal using 1 or 2 agents (Figure 2). Overall in this study, 66% of participants achieved goal on an average of 2 antihypertensive agents, demonstrating that many patients would have required ≥3 drugs to achieve BP goals (Figure 3). 10 , 18 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30

Figure 2.

Cumulative percentage of patients achieving blood pressure goal (<140/90 mm Hg) in relation to the number of antihypertensive agents used in the Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) at 5 years. Derived from Cushman et al. 10

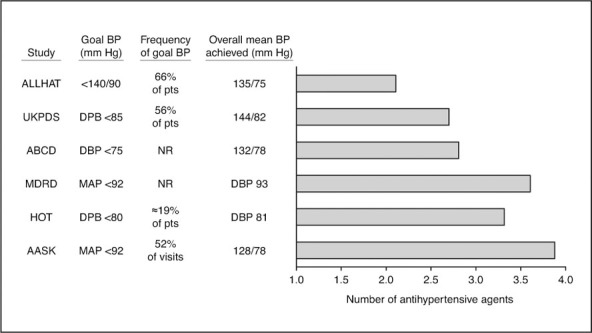

Figure 3.

Mean number of antihypertensive agents required to achieve a range of blood pressure (BP) goals in major trials. 10, 18, 27, 28, 29, 30 ABCD indicates Appropriate Blood Pressure Control in Diabetes 28 ; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease 29 ; AASK, African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension ; pts, patients; DBP, diastolic BP; NR, not reported; and MAP, mean arterial pressure; other trial acronyms are expanded in the text. Adapted from Bakris et al, 31 with permission from Elsevier

JNC 7 guidelines 6 recommend initiating therapy with 2 drugs when BP is more than 20 mm Hg above the systolic goal or 10 mm Hg above the diastolic goal. If lower goals are desired, even more drugs may be required. For example, a mean of 3.3 antihypertensive medications was required for patients to achieve a DBP target of ≤80 mm Hg in the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) trial. 27

Although not evidence‐based, a general “rule of tens” can be a useful guide for clinicians and patients, ie, every 10‐mm Hg reduction in SBP may require 1 antihypertensive agent. It is helpful to communicate that a large number of patients will need at least 2 drugs to control BP.

WHAT IS STOPPING US FROM ACHIEVING BP GOALS?

Elevated SBP is the primary factor contributing to the lack of BP control, and for patients older than 50 years, isolated systolic hypertension represents the most common form of hypertension. 6 , 32 , 33 In the Framingham Heart Study, 33 83% of participants with hypertension were at DBP goal, but only 33% were at SBP goal. SBP is a stronger predictor of cardiovascular disease risk than DBP in older individuals, and control of SBP significantly reduces cardiovascular events. 12 , 13 , 34

Poor control of hypertension is often attributed to a lack of access to health care, nonadherence with treatment, and a disproportionate burden of hypertension among less educated or disadvantaged socioeconomic groups (Table III). 35 , 36 Even for patients with access to health care and medications, however, there is a significant gap between treatment recommendations and clinical practice, despite the availability of appropriate hypertension management guidelines.

Table III.

Reasons for Poor Blood Pressure Control

Inadequate Hypertension Management

An analysis of the characteristics of patients with uncontrolled hypertension 32 showed that most cases occurred in older patients with isolated, mild systolic hypertension, who generally had access to health care and frequent contact with clinicians, suggesting what is known as “clinical (or therapeutic) inertia.” 37

This was first highlighted in a study of 800 male veterans. 38 Over a 2‐year study period in the early 1990s, 39% of patients had a BP of ≥160/90 mm Hg and only 25% achieved a BP of <140/90 mm Hg, despite an average of >6 hypertension‐related clinic visits per year. More intensive treatment (as measured by the number of increases in antihypertensive medication) was associated with better BP control; SBP declined by a mean 6.3 mm Hg among patients receiving the most intensive treatment regimen and increased by a mean 4.8 mm Hg among patients with the least intensive regimen.

Therapeutic inertia has been documented in a number of reports. 32 , 38 , 39 , 40 Most recently, Okonofua and colleagues 39 analyzed data from the 62 practices in North and South Carolina and Georgia participating in the Hypertension Initiative. They found that medications were changed in only 13.1% of visits in which patients had elevated BP. Factors associated with therapeutic inertia were stage 1 hypertension and use of fewer antihypertensive medications, as well as older age, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, congestive heart failure, and cardiovascular disease. According to their estimates, if physicians had pursued medication titration more effectively, mean SBP in this cohort would be 13.8 mm Hg lower and mean DBP 4.8 mm Hg lower, and 77.6% of patients would have achieved BP control. One important component of any optimal care strategy should be to up‐titrate antihypertensive agents in a timely manner in patients not achieving BP goal.

In the Hypertension Initiative study, 39 a 20% improvement in the proportion of visits in which medication was intensified would have increased the BP control rate from 46.2% to 65.9%.

A number of reasons have been proposed for therapeutic inertia in chronic conditions 40 :

-

•

Overestimating how many patients have reached their goal

-

•

Using unsupported reasoning to avoid intensifying the medical regimen (eg, the physician assuming that the patient would not accept more medications)

-

•

Lack of training, education, or organizational practices aimed at achieving goals, including a lack of appreciation for the magnitude of therapeutic benefit to be achieved from lower BP.

Of these, the latter is particularly important, because many physicians accept BP reduction as a surrogate for BP goal attainment. Programs such as the Hypertension Initiative are helping to address therapeutic inertia through a mix of primary care physician training, monitoring, feedback, facilitating development of policies and procedures, and providing clinical hypertension specialists for expert consultation and care. 40 Chart audit and effective feedback to providers have been recognized as important factors for improving BP control. 41 The success achieved by the VA system for BP goal attainment provides a national standard by which other programs can measure their progress toward the Healthy People 2010 goal.

Patient Adherence

There are a number of reasons why patients fail to take their medication, including the long duration of therapy, asymptomatic nature of hypertension, cost of treatment, real or perceived adverse effects, complicated drug regimens, poor rapport and communication with the physician, lack of understanding about the importance of treatment, and a general lack of motivation. 7 , 42

Patient education is important in the successful management of hypertension, because no treatment is effective in noncompliant patients. Very little information is provided to patients in physicians' offices despite its availability. One booklet from the Hypertension Education Foundation (HEF), “High Blood Pressure: What You Should Know About It and How You Can Help Your Doctor Treat It,” can be downloaded from http:www.hypertension‐foundation.org (also available from Le Jacq, Three Enterprise Drive, Shelton, CT 06484).

Adherence in patients receiving antihypertensive treatment is estimated to be between 50% and 70%, 43 and has been recognized by the World Health Organization as an important issue requiring improvement. 44 Engaging patients and their families in the process of achieving the BP goal is a critical factor for treatment success. 45 When caregivers, spouses, and families are involved in consultations and are aware of treatment strategies, there is a greater likelihood of long‐term compliance with treatment.

In a German study, adverse events were the second most common reason for antihypertensive medication changes (after lack of efficacy), accounting for 30.1% of changes. 42 Concerns about adverse effects may also explain why clinicians are reluctant to titrate medications. And yet, in blinded trials, the 5 major classes of antihypertensive agents recommended as preferred treatment in JNC 7 were associated with relatively few adverse effects. 12 , 24 , 25 , 46

A systematic review of 38 studies found that simplification of dosing regimens was a most promising method for increasing patient adherence. 47 This can be achieved with the use of fixed‐dose combinations and once‐daily medications. Also, improving patient understanding of the need to achieve and maintain BP goals is crucial for treatment success.

THE BENEFITS OF EXISTING ANTIHYPERTENSIVE AGENTS

Effects on BP and Cardiovascular Outcomes

There is now substantial evidence to support the efficacy of currently available antihypertensive agents. The BP‐lowering effects of these agents and favorable BP goal attainment rates are well documented (Table II), 10 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 46 as are benefits in target organ protection 30 , 48 , 49 and reductions in cardiovascular events. 12 , 13 , 50 , 51

A drug's expected effect on major cardiovascular outcomes is the most important factor in treatment selection. Thiazide‐type diuretics, CCBs, angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and ARBs have demonstrated the best results in cardiovascular outcomes trials. 51 Among them, thiazides are preferred as initial therapy either alone or in combination with another agent for most patients with hypertension who do not have a compelling reason to begin with another agent. 6 Many trials since the 1960s show consistent cardiovascular benefits with thiazides. In adequately powered and designed trials comparing other agents to a thiazide, such as ALLHAT, 24 other classes were not superior to a thiazide. Most patients will require multidrug therapy, and these 4 classes should be the basis of treatment in most patients.

Tolerability and Adverse Event Management

Antihypertensive agents are associated with both perceived and real adverse effects in some patients. Patients need to be informed of potential adverse events and to be assured that their clinicians will listen to them if they believe they are having an adverse effect and consider changing their anti‐hypertensive medications, if appropriate and possible. Many patients receiving antihypertensive agents assume that any symptom is a result of treatment. Physicians must explain to patients that not all events are treatment‐related, but also reassure them that any such symptom will be monitored appropriately.

Although the overall incidence is relatively low, adverse effects are troublesome for patients and can result in discontinuation of treatment. 46 Diuretics are as well or better tolerated than ACE inhibitors, CCBs, central α‐agonists, and α‐blockers. 23 , 24 , 46 For patients who have experienced adverse effects with other agents, ARBs are a useful alternate because they are well tolerated. 52 , 53

Convenience for Improving Adherence

The availability of fixed‐dose combinations provides an effective and convenient way to start 2‐drug therapy as initial treatment in patients with stage 2 hypertension, as recommended in JNC 7. 6 The use of a single pill once daily makes treatment more convenient for patients and may improve adherence. Studies have also shown that combining diuretics with other antihypertensive agents is more effective than monotherapy with the same agents and than most other combinations 54 and reduces the risk of some adverse effects. 55

The multiple benefits of currently available antihypertensive agents, including BP‐lowering effects; reduction of cardiovascular, diabetic, and renal events; tolerability; and convenience should encourage clinicians to treat hypertension to recommended goals, and also help patients remain compliant with treatment.

SUMMARY

The importance of achieving BP goals in hypertensive patients has been highlighted in clinical guidelines as the most clinically relevant measure of BP control. Unfortunately, guideline recommendations can be successful only when they are implemented effectively. With only about one third of hypertensive patients in the United States achieving BP goals, there is a significant gap between recommendations and what is being achieved.

Currently available antihypertensive agents are effective, convenient, and well tolerated. Several major clinical trials and experience within the Veterans Affairs medical system report that recommended BP goals are achievable with currently available antihypertensive agents, 23 , 24 , 26 , 27 even in difficult‐to‐manage patients, if a forced titration protocol is used in conjunction with monitoring and feedback.

The most important factors leading to less‐than‐ideal results appear to be a lack of patient and clinician awareness and clinical inertia leading to inadequate titration of medications.

RECOMMENDATIONS

For the successful results observed in clinical trials to be translated into clinical practice, clinicians should consider instituting the following policies: (1) educate themselves as to the importance of treating to BP goal; (2) use a consistent therapeutic approach to get patients to goal; (3) attain BP goal in a timely manner; and (4) educate, engage, and motivate patients and their families to maintain adherence once BP targets are achieved. A good clinician‐patient relationship is an essential cornerstone to the achievement of BP goals. As the JNC 7 report states, “[T]he most effective therapy prescribed by the most careful clinician will control hypertension only if the patient is motivated… Motivation improves when patients have positive experiences with, and trust in, their clinicians.” 6 The use of logical combinations of antihypertensive agents and judicious involvement of other health care professionals are also vital for ensuring that patients have the best possible chance of achieving BP goal.

By combining persistent hypertension management with effective, convenient, and well‐tolerated treatment regimens, it may still be possible to achieve a BP control rate of 50% by 2010. 6 Given the benefits of attaining this national goal, a greater integrated effort is warranted.

References

- 1. American Heart Association. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics‐2005 Update. Dallas, TX: American Heart Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Evidence‐based health policy‐lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Science. 1996;274:740–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fields LE, Burt VL, Cutler JA, et al. The burden of adult hypertension in the United States 1999 to 2000: a rising tide. Hypertension. 2004;44:398–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Neal B, MacMahon S, Chapman N. Effects of ACE inhibitors, calcium antagonists, and other blood‐pressure‐lowering drugs: results of prospectively designed overviews of randomised trials. Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists' Collaboration. Lancet. 2000;356:1955–1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988–2000. JAMA. 2003;290:199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. US Dept of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Egan BM, Basile JN. Controlling blood pressure in 50% of all hypertensive patients: an achievable goal in the Healthy People 2010 report? J Investig Med. 2003;51:373–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moser M. Hypertension treatment—a success study. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2006;8:313–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cushman WC, Ford CE, Cutler JA, et al. Success and predictors of blood pressure control in diverse North American settings: the Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2002;4:393–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chrysant SG, Marbury TC, Silfani TN. Use of 24‐hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring to assess blood pressure control: a comparison of olmesartan medoxomil and amlodipine besylate. Blood Press Monit. 2006;11:135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA. 1991;265:3255–3264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Staessen JA, Fagard R, Thijs L, et al. Randomised double‐blind comparison of placebo and active treatment for older patients with isolated systolic hypertension. The Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst‐Eur) Trial Investigators. Lancet. 1997;350:757–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressures averaging 115 through 129 mm Hg. JAMA. 1967;202:1028–1034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. II. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressure averaging 90 through 114 mm Hg. JAMA. 1970;213:1143–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Benetos A, Thomas F, Bean KE, et al. Why cardiovascular mortality is higher in treated hypertensives versus subjects of the same age, in the general population. J Hypertens. 2003;21:1635–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Borghi C, Dormi A, D'Addato S, et al. Trends in blood pressure control and antihypertensive treatment in clinical practice: the Brisighella Heart Study. J Hypertens. 2004;22:1707–1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ. 1998;317:703–713. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, et al. Age‐specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta‐analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903–1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Godley PJ, Maue SK, Farrelly EW, et al. The need for improved medical management of patients with concomitant hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:206–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hosie J, Wiklund I. Managing hypertension in general practice: can we do better? J Hum Hypertens. 1995;9(suppl 2):S15–S18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pepine CJ, Handberg EM, Cooper‐DeHoff RM, et al. A calcium antagonist vs a non‐calcium antagonist hypertension treatment strategy for patients with coronary artery disease. The International Verapamil‐Trandolapril Study (INVEST): a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2805–2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Black HR, Elliott WJ, Grandits G, et al. Principal results of the Controlled Onset Verapamil Investigation of Cardiovascular End Points (CONVINCE) trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2073–2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high‐risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) [published corrections appear in JAMA. 2003;289:178 and JAMA. 2004;291:2196].JAMA. 2002;288:2981–2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dahlof B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a ran domised trial against atenolol. Lancet. 2002;359:995–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Berlowitz DR, Cushman WC, Glassman P. Hypertension in adults across age groups. JAMA. 2005;294:2970–2971 [author reply 2971–2972]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al. Effects of intensive blood‐pressure lowering and low‐dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. HOT Study Group. Lancet. 1998;351:1755–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Estacio RO, Jeffers BW, Gifford N, et al. Effect of blood pressure control on diabetic microvascular complications in patients with hypertension and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(suppl 2):B54–B64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hebert LA, Kusek JW, Greene T, et al. Effects of blood pressure control on progressive renal disease in blacks and whites. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Hypertension. 1997;30(3 pt 1):428–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wright JT Jr, Bakris G, Greene T, et al. Effect of blood pres sure lowering and antihypertensive drug class on progression of hypertensive kidney disease: results from the AASK trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2421–2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bakris GL, Williams M, Dworkin L, et al. Preserving renal function in adults with hypertension and diabetes: a consensus approach. National Kidney Foundation Hypertension and Diabetes Executive Committees Working Group. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36:646–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hyman DJ, Pavlik VN. Characteristics of patients with uncontrolled hypertension in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lloyd‐Jones DM, Evans JC, Larson MG, et al. Differential control of systolic and diastolic blood pressure: factors associated with lack of blood pressure control in the community. Hypertension. 2000;36:594–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stamler J, Stamler R, Neaton JD. Blood pressure, systolic and diastolic, and cardiovascular risks. US population data. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:598–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Munger MA. Critical overview of antihypertensive therapies: what is preventing us from getting there? Am J Manag Care. 2000;6(4 suppl):S211–S221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Weber MA. Strategies for improving blood pressure control. Am J Hypertens. 1998;11:897–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:825–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Berlowitz DR, Ash AS, Hickey EC, et al. Inadequate management of blood pressure in a hypertensive population. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1957–1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Okonofua EC, Simpson KN, Jesri A, et al. Therapeutic inertia is an impediment to achieving the Healthy People 2010 blood pressure control goals. Hypertension. 2006;47:345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Egan BM, Lackland DT, Basile JN. American Society of Hypertension regional chapters: leveraging the impact of the clinical hypertension specialist in the local community. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15(4 pt 1):372–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Towsend RR, Shulkin DJ, Bernard D. Improved outpatient hypertension control with disease management guidelines [abstract]. Am J Hypertens. 1999;12:88. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dusing R, Weisser B, Mengden T, et al. Changes in antihypertensive therapy—the role of adverse effects and compliance. Blood Press. 1998;7:313–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Caro JJ, Speckman JL, Salas M, et al. Effect of initial drug choice on persistence with antihypertensive therapy: the importance of actual practice data. CMAJ. 1999;160:41–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Burkhart PV, Sabate E. Adherence to long‐term therapies: evidence for action. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2003;35:207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Roter DL, Hall JA, Merisca R, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to improve patient compliance: a meta‐analysis. MedCare. 1998;36:1138–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Materson BJ, Reda DJ, Cushman WC, et al. Single‐drug therapy for hypertension in men. A comparison of six antihypertensive agents with placebo. The Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:914–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schroeder K, Fahey T, Ebrahim S. How can we improve adherence to blood pressure‐lowering medication in ambulatory care? Systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:722–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Brenner BM, Cooper ME, De Zeeuw D, et al. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:861–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, et al. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin‐receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:851–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Staessen JA, Thijisq L, Fagard R, et al. Effects of immediate versus delayed antihypertensive therapy on outcome in the Systolic Hypertension in Europe Trial. J Hypertens. 2004;22:847–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Turnbull F, Neal B, Algert C, et al. Effects of different blood pressure‐lowering regimens on major cardiovascular events in individuals with and without diabetes mellitus: results of prospectively designed overviews of randomized trials. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1410–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gillis JC, Markham A. Irbesartan. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in the management of hypertension. Drugs. 1997;54:885–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Markham A, Goa KL. Valsartan. A review of its pharmacology and therapeutic use in essential hypertension. Drugs. 1997;54:299–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Materson BJ, Reda DJ, Cushman WC, et al. Results of combination anti‐hypertensive therapy after failure of each of the components. Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Anti‐hypertensive Agents. J Hum Hypertens. 1995;9:791–796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kuschnir E, Acuna E, Sevilla D, et al. Treatment of patients with essential hypertension: amlodipine 5 mg/benazepril 20 mg compared with amlodipine 5 mg, benazepril 20 mg, and placebo. Clin Ther. 1996;18:1213–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]