Abstract

AIM:

We conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the efficacy and safety of gefapixant, a novel P2X3 receptor antagonist, in patients with chronic cough.

METHODS:

We searched four databases for randomized controlled trials (RCTs). We assessed the cough frequency, severity, total Leicester cough questionnaire (LCQ) score, and adverse events. We analyzed the data using Open Meta-Analyst and Review Manager Software.

RESULTS:

We included four unique studies (comprising five stand-alone RCTs) with 439 patients. Compared to placebo, gefapixant had positive anti-tussive effects by improving awake cough frequency (mean difference [MD] = −5.27, 95% confidence interval [CI] [−6.12, −4.42], P < 0.00001), night cough frequency (MD = −3.71, 95% CI [−6.57, −0.85], P = 0. 01), 24 h cough frequency (MD = −4.18, 95% CI [−5.01, −3.36], P < 0.00001), cough severity using the Visual Analog Scale (MD = −13.36, 95% CI [−17.80, −8.92], P < 0.00001), cough severity diary (MD = −0.88, 95% CI [−1.25, −0.51], P < 0.00001), and total LCQ score (MD = 2.00, 95% CI [1.15, 2.86], P = 0. 00001). Meta-regression analyses showed a positive correlation between the gefapixant dose and the incidence of any adverse event (relative risk [RR] = 0.239, 95% CI [0.093, 1.839], P = 0.001) and incidence of adverse event related to treatment (RR = 0.520, 95% CI [0.117, 0.922], P = 0.011).

CONCLUSIONS:

In patient with chronic cough, gefapixant exhibits favorable anti-tussive outcomes by improving the cough frequency, severity, and quality of life. While gefapixant is largely tolerable, its side effects (notably taste alteration) are dose dependent.

Keywords: AF-219, chronic cough, gefapixant, MK-7264, P2X3 antagonist

Cough is considered the most frequent symptom which seeks clinical advice in the United States.[1] According to epidemiological studies, it is estimated that 4%–10% of adults worldwide suffer from cough.[2] Despite extensive research endeavors, an available, effective, and approved therapy for cough has not been discovered yet.[2,3] It is approximated that 12% of adult patients with cough progress to the stage of chronic cough that lasts 8 weeks or longer.[4]

Gastroesophageal reflux disease, asthma, and nasal/sinus illnesses constitute the most common sources of chronic cough in patients with normal chest radiological results. Furthermore, patients with chronic cough are characteristically liable to many disorders, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease, pulmonary fibrosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and bronchiectasis.[5] Several environmental factors may induce chronic cough, such as temperature changes, fragrances, and smokes.[6] Other factors, such as citric acid,[7] mannitol,[8] capsaicin,[9] and other inhaled tussive agents, may also lead to an increased occurrence of cough.

Chronic refractory cough is described as a persistent cough continuing for more than 8 weeks in spite of evaluation and treatment according to the most contemporary guidelines.[10] The rough incidence of chronic refractory cough can reach up to 50% in patients with chronic cough, despite extensive investigation and treatment trials.[11,12] Cough hypersensitivity syndrome, a cough instigated by stimuli that do not often trigger cough, can be related to chronic refractory cough and ascribed to disorders in sensory neuronal functions.[13] Few therapeutic choices are in place for patients with chronic refractory cough caused by neuronal functional disorders, such as gabapentin, morphine, amitriptyline, and behavioral therapies.[14,15]

The cough reflex is induced by afferent fibers to the vagus nerve. These fibers include Aδ and C fibers, which are sensitive to mechanical and chemical stimulation, respectively.[16] Purinergic receptors, such as P2X3 receptors, are adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-gated ion channels that are found in the afferent neurons ascending from the cranial and dorsal root ganglia.[17,18] Preclinical evidence suggests that P2X3 receptors are conveyed in vagal C fibers which innervate the airways in guinea pigs and affected by ATP.[19,20] During ATP and histamine exposure, the cough reflex is enhanced due to the stimulation of P2X3 receptors.[21,22]

Gefapixant (also known as AF-219 and MK-7264), an antagonist of P2X3 receptor, has recently shown notable efficacy as a treatment for chronic cough through controlling the afferent sensitivity of upper and lower respiratory airways.[23] The first trial of gefapixant revealed a 75% decline in daytime cough with improvement in patient-reported outcomes. However, after the administration of a high dose of gefapixant, the taste sensation was altered due to its effect on gustatory afferents.[24] Other studies measured the outcomes at different doses.[25,26,27] We carried out this meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to gauge the clinical efficacy and safety of gefapixant in patients with chronic cough.

Methods

Protocol

We used the guidelines stated in the Cochrane's handbook of systematic reviews of intervention[28] and followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement[29] in conducting this research.

Literature search

We executed a search of four electronic databases, namely PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science. We used the following keywords: “MK-7264,” “AF-219,” “Gefapixant,” and “cough” to identify studies that met our eligibility criteria.

Eligibility criteria

We selected all phase II-III RCTs that gathered the following criteria for our PICO evidence-based research question: (1) Patients: individuals with chronic cough irrespective of age, (2) Intervention: gefapixant, (3) Comparator: placebo, and (4) Outcomes: safety and efficacy. We excluded studies reporting animal trials, abstracts only, and any study designs other than RCTs. The comparator placebo was selected, because it is the most commonly used one. In addition, no studies were available to compare gefapixant versus any other active comparator.

Screening of results

After retrieving the results from the literature search stage, we screened these results in two steps. The first step included title and abstract screening. The second step included full-text screening. Moreover, we screened the references of the included research studies.

Data extraction

We extracted four major categories from the included studies, namely (1) baseline characteristics of patients, (2) outcome measures, (3) general features of included papers, and (4) data for Cochrane risk of bias tool domains. Information about baseline characteristics of patients included age, gender, race, body mass index, cough duration, the ratio of the forced expiratory volume in the first 1 s to the forced vital capacity of the lungs, and the baseline of measured outcomes. Information about the outcomes measures for the analysis included efficacy and safety outcomes. Efficacy outcomes included awake cough frequency expressed as number of coughs per hour (c/h), night cough frequency (c/h), 24 h cough frequency (c/h), cough severity by 100-mm Visual Analog Scale (VAS) (a score of 0 reflects no pain at all, and as score of 100 reflects worst pain imaginable), cough severity diary, and total Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ) score for the assessment of quality of life. Safety outcomes included any adverse event, discontinuation due to adverse event, serious adverse event, adverse event related to treatment, renal or urological event, dysgeusia, hypogeusia, ageusia, headache, upper respiratory tract infection, oral paraesthesia, oral hypoesthesia, cough, nausea, and urinary tract infection. Information about the general features of included studies included ClinicalTrials.gov identifier (NCT number), design, doses, and conclusions. When we extracted the data, we found two trials with the same first author and year of publication. One of these trials included two studies,[25] and we reported them as two stand-alone studies, as follows: S1 and S2. The third study was named S3.[26]

Quality assessment

We evaluated the quality of included studies according to the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool (explained in Chapter 8.5 of the Cochrane handbook of systematic reviews of interventions 5.1.0). The risk of bias tool assessed randomization, blinding, outcomes, and other possible sources of bias. We judged each category as low, high, or unclear risk of bias.

Data synthesis

The efficacy outcomes were continuous data, and we analyzed them as mean difference (MD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) in a fixed-effect model using the inverse-variance method. The safety outcomes were dichotomous data, and we pooled them as relative risk (RR) and 95% CI in a random-effect model using the DerSimonian and Laird method. The analysis of continuous and dichotomous was conducted using the Review Manager Software version 5.3 and the Open Meta-Analyst Software, respectively. Significant heterogeneity was considered when I-square test (I2) >50% and Chi-square P < 0.1.

Results

Search results and summary of included studies

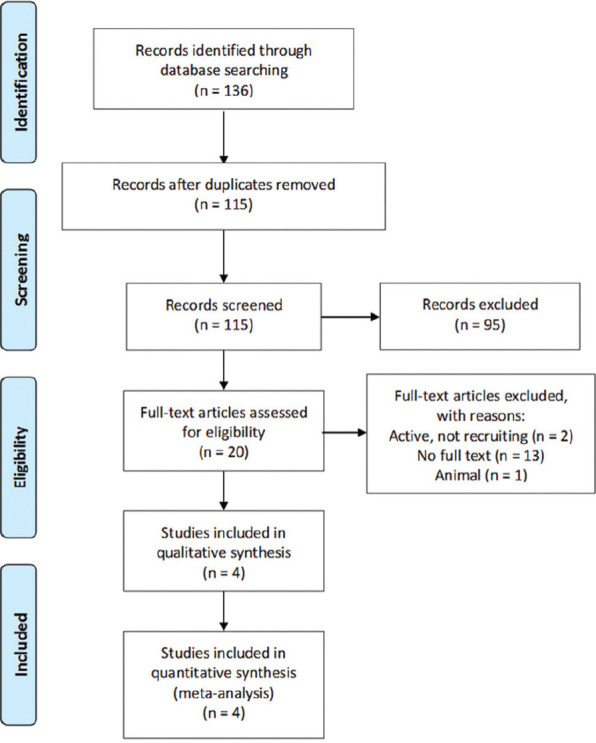

Our literature search retrieved 136 records, 21 of them were duplicate records, and 115 records progressed to title and abstract screening. Out of 20 records extracted for full-text screening, 16 citations were excluded, and finally, four citations (reporting five stand-alone studies) were included in our meta-analysis.[24,25,26,27] A detailed summary of the study selection process is shown in Figure 1 Our meta-analysis included a total of 439 patients; 276 of them treated with gefapixant, and the rest (n = 163) received placebo. The mean age of the study participants was 49.03 years. Smith et al. S1 and S2 were presented in one study,[25] and we reported them as two separate studies. Smith et al. S3 was an independent study.[26] Baseline characteristics, baseline outcomes, and summary of included studies are shown in Tables 1-3, respectively.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram for our literature search

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients included in the studies

| ID | Number | Age in years | Female/male | White/other | BMI | Cough duration in days | FEV1/FVC ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smith S1 2020 | 29 | 63.2±7.35 | 25/4 | 28/1 | 26.6±4.82 | 15.4±13.47 | 77±8.75 |

| Smith S2 2020 | 30 | 60.2±11.06 | 24/6 | 28/2 | 26.5±4.82 | 13.2±10.22 | 82±10.5 |

| Smith S3 2020 | 253 | 60.2±9.9 | 193/60 | 234/19 | 27.7±4.7 | 14.5±11.7 | 81.7±12.2 |

| Morice 2019 | 24 | 61.1±8.69 | 21/3 | - | - | 14.6±9.89 | - |

| Abdulqawi 2015 | 24 | 49.5±36.25 | 18/6 | 24/0 | 26.96±11.82 | 12.3±17.3 | 78.36±16.07 |

Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation. BMI=Body mass index, FEV1/FVC ratio=The ratio of the forced expiratory volume in the first 1 s to the forced vital capacity of the lungs

Table 3.

Baseline summary of the included studies

| ID | NCT | Design | Doses | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smith S1 2020 Smith S2 2020 |

NCT02349425 | RCT Phase 2 |

50, 100, 150, 200 mg 7.5, 15, 30, 50 mg |

Gefapixant doses ≥30 mg produced maximal improvements in cough frequency and cough severity measures improved at similar doses. Taste disturbance exhibited a different relationship with dose, apparently maximal at doses ≥150 mg |

| Smith S3 2020 | NCT02612610 | RCT Phase 2 |

7.5, 20, 50 mg | Gefapixant at a dose of 50 mg twice daily significantly reduced cough frequency in patients with chronic refractory cough or unexplained chronic cough after 12 weeks of treatment |

| Morice 2019 | NCT02476890 | RCT Phase 2 |

100 mg | The ATP-evoked cough was significantly inhibited by gefapixant 100 mg demonstrating peripheral target engagement. Cough count and severity were reduced in patients with chronic cough |

| Abdulqawi 2015 | NCT01432730 | RCT Phase 2 |

600 mg | P2X3 receptors seem to have a critical role in mediation of cough neuronal hypersensitivity. Antagonists of P2X3 receptors such as AF-219 are a promising new group of antitussives |

RCT=Randomized controlled trial, ATP=Adenosine triphosphate

Table 2.

Baseline outcomes of patients in the included studies

| ID | Arm | Total | Awake cough frequency (c/h) | Night cough frequency (c/h) | 24 h cough frequency (c/h) | Cough severity VAS (mm) | Cough severity diary | Total LCQ score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smith S1 2020 | Drug | 28 | 54.5±41.1 | 8.3±9.3 | 39.7±28.4 | 58.4±18.7 | 4.2±1.9 | 12.3±3.1 |

| Placebo | 28 | 52.8±40.4 | 8.3±9.3 | 37.9±27.5 | 52.2±19.2 | 3.7±1.6 | 13.1±3.4 | |

| Smith S2 2020 | Drug | 30 | 49.6±44.0 | 10.1±26.8 | 36.3±32.3 | 54.5±24.3 | 4.5±2.0 | 12.6±4.0 |

| Placebo | 29 | 46.1±39.8 | 5.6±7.6 | 32.2±28.0 | 57.2±23.7 | 4.5±1.9 | 13.3±3.8 | |

| Smith S3 2020 | 7.5 mg | 59 | 27.4±2.7 | - | 20.0±2.7 | 56.7±20.7 | 4.1±1.7 | 12.1±2.7 |

| 20 mg | 59 | 24.1±3.0 | - | 17.6±3.0 | 58.3±25.1 | 4.2±2.1 | 12.0±3.3 | |

| 50 mg | 57 | 28.8±2.2 | - | 21.9±2.2 | 57.9±19.7 | 4.3±1.8 | 11.4±2.8 | |

| Placebo | 61 | 27.6±2.3 | - | 20.5±2.2 | 57.4±23.1 | 4.1±1.8 | 12.2±2.8 | |

| Morice 2019 | 100 mg | 24 | - | - | - | 68.6±17.45 | - | - |

| Placebo | 24 | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Abdulqawi 2015 | 600 mg | 19 | 37.09±32.23 | 4.34±7.79 | 26.63±22.63 | - | - | - |

| Placebo | 21 | 65.45±163.36 | 7.78±23.80 | 44.70±105.16 | - | - | - |

Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation. c/h=Cough per hour, LCQ=Leicester Cough Questionnaire, VAS=Visual Analog Scale

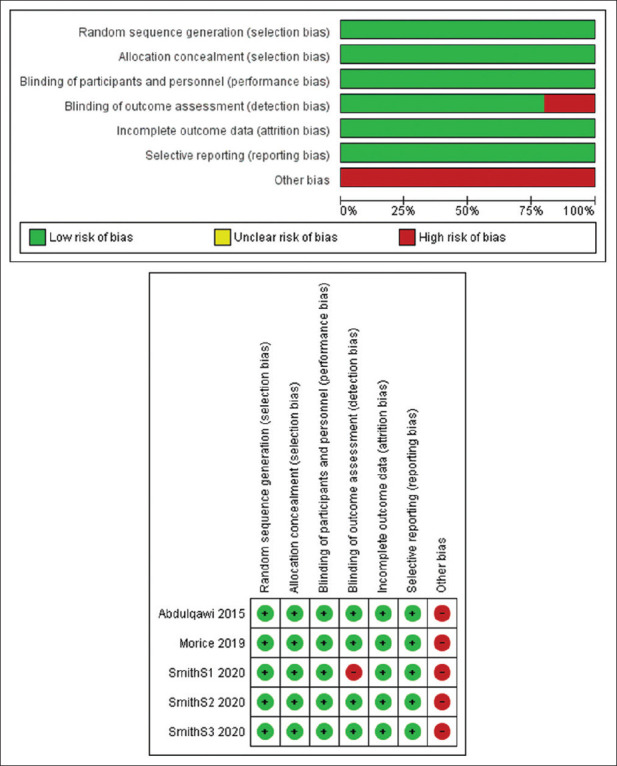

Quality assessment of the included studies

We found an overall low risk of bias in the selection, attrition, reporting, and detection bias domains. Only Smith et al. S1[25] was judged as a high risk regarding the detection bias domain. All studies were funded by a pharmaceutical industry; therefore, we scored the other bias (funding bias) as high risk. Risk of bias was assessed by two independent authors and disagreements, if any, were resolved by a third independent author. The risk of bias summary and graph is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary and graph

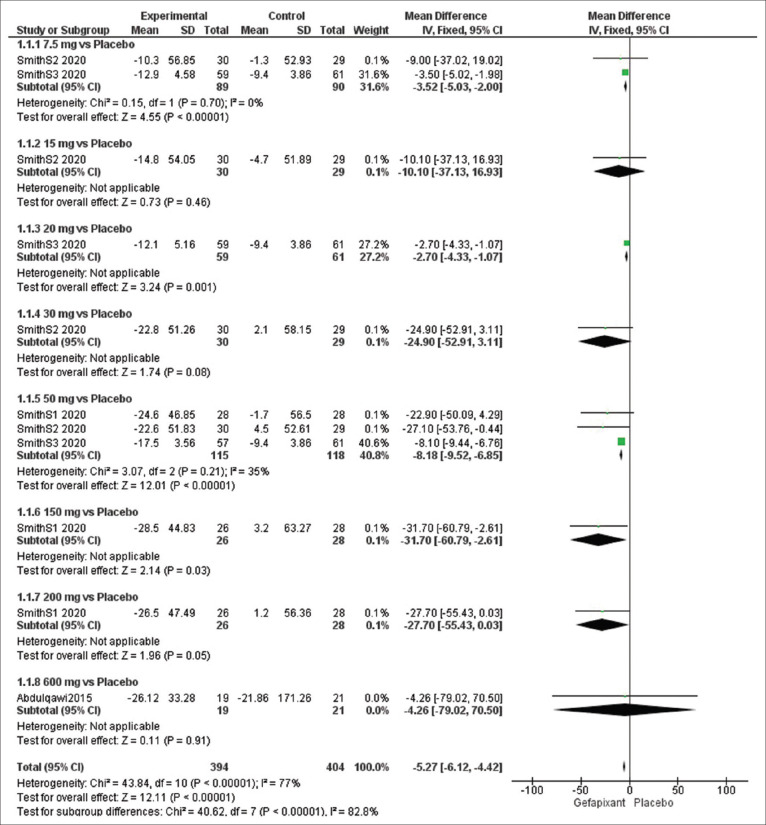

Efficacy outcome: awake cough frequency (c/h)

The overall effect estimates of awake cough frequency exhibited a significant difference between the gefapixant and placebo groups (MD = −5.27, 95% CI [−6.12, −4.42], P < 0 0.00001) and we detected heterogeneity (P < 0.00001, I2 = 77%).

To solve this heterogeneity, we did a sub-group analysis according to the dose of gefapixant and the results were as follows: at dose of 7.5 mg (MD = −3.52, 95% CI [−5.03, −2.00], P < 0.00001) and 50 mg (MD = −8.18, 95% CI [−9.52, −6.85], P < 0.00001). No heterogeneity was detected at 7.5 mg (P = 0.70, I2 = 0%) and 50 mg (P = 0.21, I2 =35%) [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Forest plots for the analysis of awake cough frequency

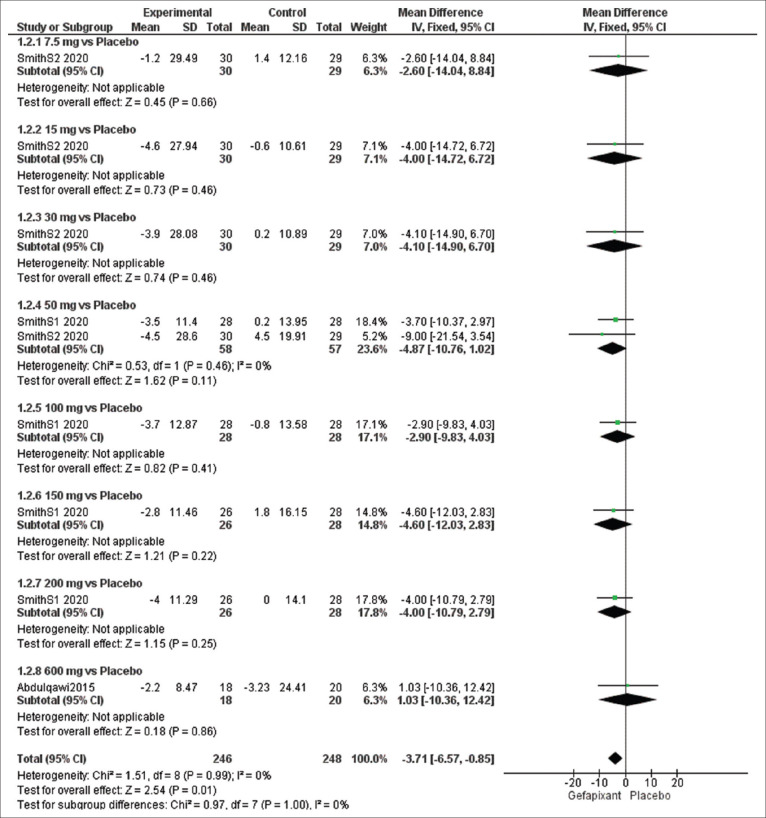

Efficacy outcome: night cough frequency (c/h)

The overall effect estimates of night cough frequency showed a significant change between the gefapixant and placebo groups (MD = −3.71, 95% CI [−6.57, −0.85], P = 0.01), and the results were homogeneous (P = 0.99, I2 = 0%). No significant difference was detected at dose of 50 mg (MD = −4.87, 95% CI [−10.76, 1.02], P = 0.11). The pooled results were homogeneous (P = 0.46, I2 = 0%) [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Forest plots for the analysis of night cough frequency

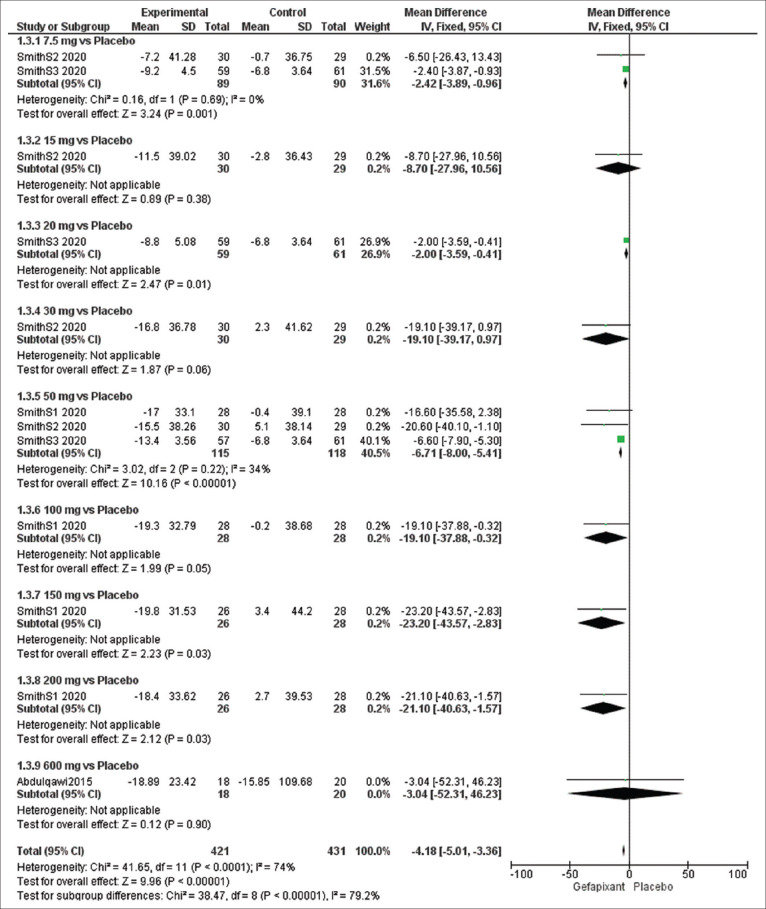

Efficacy outcome: 24-h cough frequency (c/h)

The overall effect estimates of 24-h cough frequency showed a significant difference between the gefapixant and placebo groups (MD = −4.18, 95% CI [−5.01, −3.36], P < 0.00001), and the results were heterogeneous (P < 0.0001, I2 = 74%).

The results were homogeneous at a sub-group analysis of 7.5 mg (P = 0.69, I2 = 0%) and 50 mg (P = 0.22, I2 = 34%) and significantly favored the treatment group at dose of 7.5 mg (MD = −2.42, 95% CI [−3.89, −0.96], P = 0.001) and 50 mg (MD = −6.71, 95% CI [−8.00, −5.41], P < 0.00001) [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Forest plots for the analysis of 24-h cough frequency

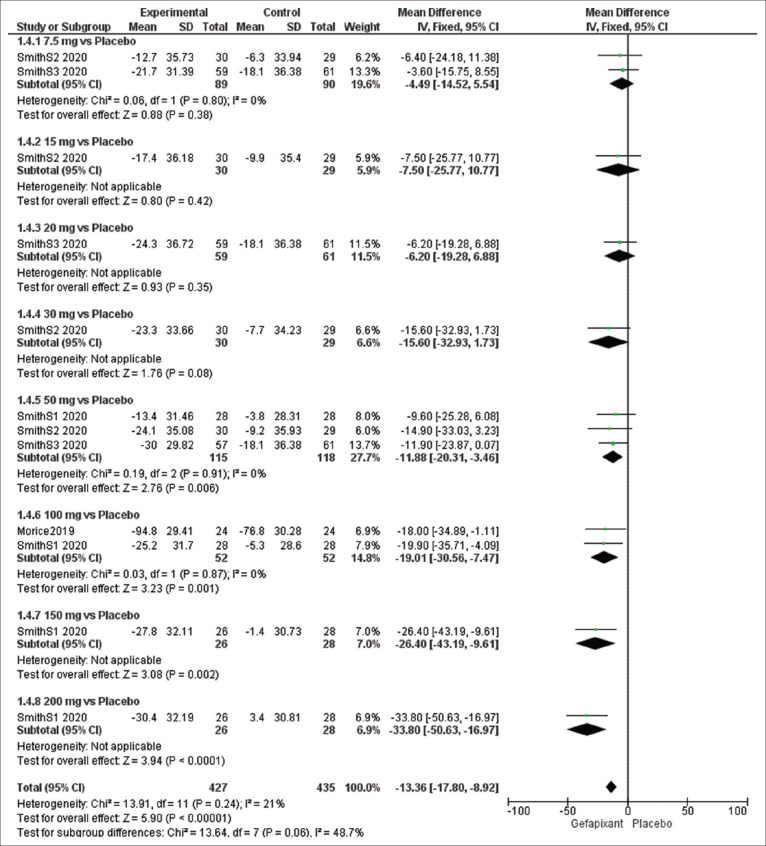

Efficacy outcome: cough severity using Visual Analog Scale (mm)

The overall pooled results of cough severity using VAS significantly favored the gefapixant group over the placebo group (MD = −13.36, 95% CI [−17.80, −8.92], P < 0.00001), and the results were homogeneous (P = 0.24, I2 = 21%).

The results of subgroup analysis were significant at dose of 50 mg (MD = −11.88, 95% CI [−20.31, −3.46], P = 0.006) and 100 mg (MD = −19.01, 95% CI [−30.56, −7.47], P = 0.001) while the results were insignificant at dose of 7.5 mg (MD = −4.49, 95% CI [−14.52, 5.54], P = 0.38). No heterogeneity was detected in the sub-group analysis of 7.5 mg (P = 0.80, I2 = 0%), 50 mg (P = 0.91, I2 = 0%), and 100 mg (P = 0.87, I2 = 0%) [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Forest plots for the analysis of cough severity using visual analogue scale

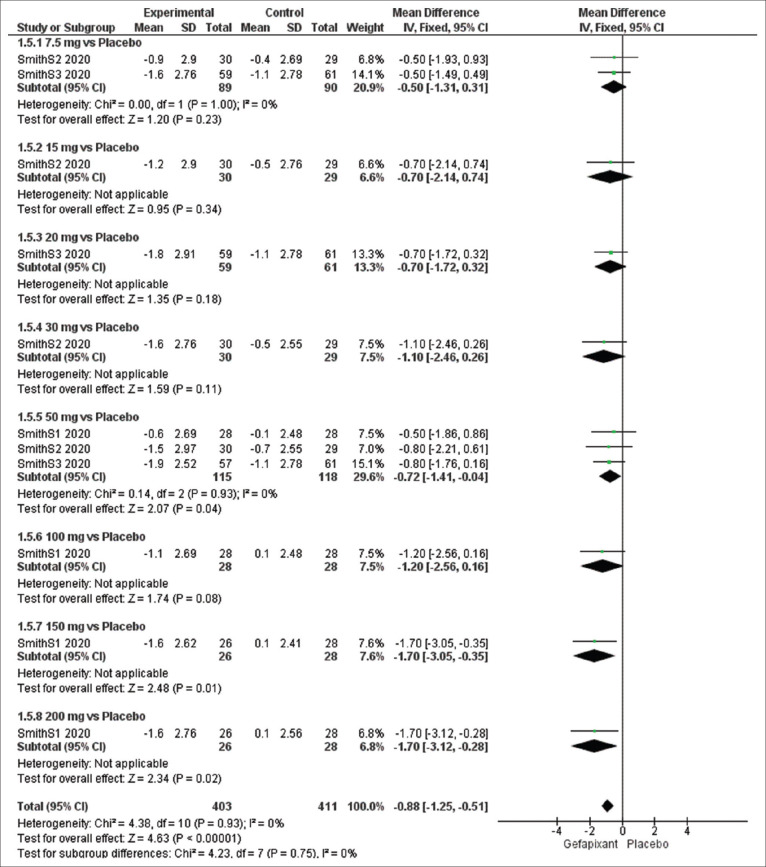

Efficacy outcome: cough severity diary

The overall pooled results of cough severity diary significantly favored the gefapixant group over the placebo group (MD = −0.88, 95% CI [−1.25, −0.51], P < 0.00001), and the results were homogeneous (P = 0.93, I2 =21%).

The pooled results were significant at dose of 50 mg (MD = −0.72, 95% CI [−1.41, −0.04], P = 0.04) and insignificant at 7.5 mg (MD = −0.50, 95% CI [−1.31, 0.31], P = 0.23). No heterogeneity was detected in subgroup of 7.5 mg (P = 1.00, I2 =0%) and 50 mg (P = 0.93, I2 = 0%) [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

Forest plots for the analysis of cough severity diary

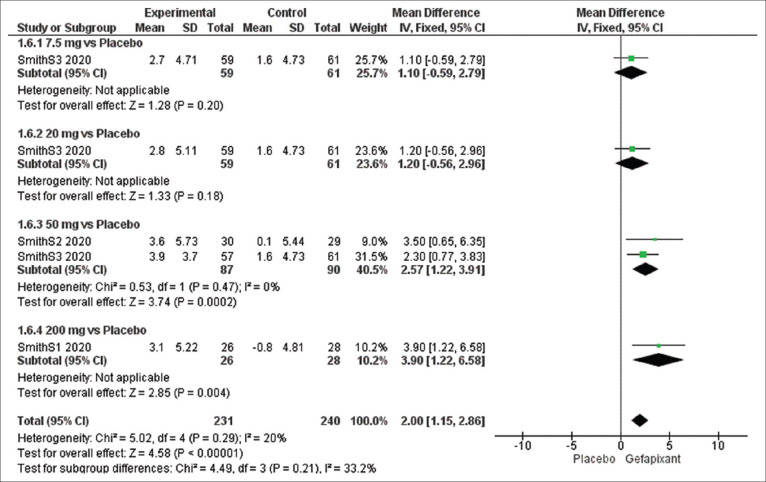

Efficacy outcome: total Leicester cough questionnaire score

The overall effect estimates of total LCQ score showed a significant variance among the two groups favoring gefapixant group (MD = 2.00, 95% CI [1.15, 2.86], P = 0. 00001), and the results were homogeneous (P = 0.29, I2 = 20%).

The effect estimates were significant at dose of 50 mg (MD = 2.57, 95% CI [1.22, 3.91], P = 0.0002), and the pooled results were homogeneous (P = 0.47, I2 = 0%) [Figure 8].

Figure 8.

Forest plots for the analysis of total Leicester Cough Questionnaire score

Safety outcomes

The overall effect estimate showed a significant change between the gefapixant and placebo groups regarding any adverse event (RR = 1.567, 95% CI [1.335, 1.839], P < 0.001), pooled results were heterogeneous (P = 0.025, I2 = 50%). Meta-regression analysis showed a positive correlation between the gefapixant dose and the incidence of any adverse events (RR = 0.239, 95% CI [0.093, 1.839], P = 0.001).

The overall effect estimate depicted a substantial change between the gefapixant and placebo groups regarding adverse events related to treatment (RR = 3.301, 95% CI [2.099, 5.190], P < 0.001), pooled results were heterogeneous (P < 0.001, I2 = 74%). Meta-regression analysis showed a positive correlation between the gefapixant dose and the incidence of adverse events related to treatment (RR = 0.520, 95% CI [0.117, 0.922], P = 0.011).

The overall effect estimates presented a significant variance between the two groups regarding discontinuation due to adverse events (RR = 2.135, 95% CI [1.092, 0.385], P = 0.027) and an insignificant variance regarding serious adverse events (RR = 1.102, 95% CI [0.437, 2.780], P = 0.837). The pooled results were homogeneous (P = 0.975, I2 = 0% and P = 1.00, I2 = 0%, respectively).

The overall effect estimates of adverse events revealed a significant difference between the gefapixant and placebo groups regarding dysgeusia (RR = 9.974, 95% CI [6.006, 16.565], P < 0.001), hypogeusia (RR = 8.538, 95% CI [3.429, 21.260], P < 0.001), ageusia (RR = 3.594, 95% CI [1.542, 8.375], P = 0.003), headache (RR = 2.316, 95% CI [1.193, 4.494], P = 0.013), upper respiratory tract infection (RR = 3.029, 95% CI [1.363, 6.732], P = 0.007), cough (RR = 2.270, 95% CI [1.038, 4.961], P = 0.040), nausea (RR = 7.253, 95% CI [1.909, 27.555], P = 0.004), and urinary tract infection (RR = 1.644, 95% CI [0.600, 4.506], P = 0.334). Conversely, the overall effect estimates of adverse events revealed an insignificant difference between the gefapixant and placebo groups regarding renal or urological events (RR = 0.839, 95% CI [0.445, 1.580], P = 0.586), oral paraesthesia (RR = 1.489, 95% CI [0.849, 2.612], P = 0.165), and oral hypoesthesia (RR = 2.042, 95% CI [0.987, 4.226], P = 0.054). All the pooled results were homogeneous. Figures of the safety outcomes are presented in Supplementary File 1.

Discussion

This study is the first meta-analysis that holistically scrutinized the effect of gefapixant as a novel treatment in patients with chronic cough. Our findings showed that gefapixant exhibits favorable efficacy in patients with chronic cough by improving the frequency of cough (awake, night, and 24 h), severity of cough (VAS and diary), and quality of life (LCQ score). On the other hand, gefapixant was associated with some side effects. In a descending sequence, the top five side effects comprised dysgeusia, hypogeusia, ageusia, nausea, and upper respiratory tract infection. We observed that the gefapixant dose positively correlated with the incidence of any adverse event (when compared to placebo) and adverse events related to treatment (within gefapixant groups). Most importantly, the increased doses of gefapixant were not substantially associated with significant serious adverse events.

Chronic refractory cough is described as a persistent cough continuing for more than 8 weeks in spite of evaluation and treatment according to the most contemporary guidelines.[30,31,32] Cough reflex hypersensitivity is a distinct facet of chronic refractory cough which involves both central and peripheral sensitization of the cough reflex.[33,34] Mechanistically, in patients with chronic cough, long-lasting inflammation taking place in the esophagus and lungs increases the afferent nerve excitation that results in a referred perception of throat scratchiness as well as a diminished cough threshold.[35] The diminished cough threshold in chronic refractory cough is correlated with a high expression of TRPV1 receptors on airway nerves.[36] The dynamic reforms in the expression of TRPA1, TRPV1, and P2X3 receptors, and the development of central and peripheral cough reflex sensitization is assumed to transform cough into a cough hypersensitivity syndrome rather than a defensive reflex.[37]

Ryan et al.[11] and Song and Chung[38] reviewed several centrally and peripherally acting drugs employed in the treatment of chronic cough. The authors reported anti-tussive effects of some neuromodulators, such as opiates, amitriptyline, gabapentin, and pregabalin. These trials of neuromodulators were conducted due to the resemblance between the functional mechanism of cough and neuropathic pain; not based on the neurobiological knowledge of cough. Overall, the results of these neuromodulators demonstrated unfavorable outcomes in terms of safety and efficacy in patients with chronic cough. The peripherally acting drugs, especially P2X3 receptor antagonists, displayed the most encouraging anti-tussive impact on chronic cough.[37,38]

Garceau and Chauret[39] reported that BLU-5937 is currently undergoing clinical phase I testing for the management of chronic cough. BLU-5937 was chosen as a potential therapeutic for the management of chronic cough owing to its high-binding affinity and potency for P2X3 receptors, robust anti-tussive actions, outstanding tolerability, and expected pharmacokinetic actions in humans. Recently, Obrecht et al.[40] identified aurintricarboxylic acid as a robust allosteric antagonist of P2X3 and P2X1 receptors. However, its utility in the treatment of chronic cough has not been examined yet.

Cough can be an incapacitating symptom in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Gefapixant has been shown to exhibit decreased anti-tussive effects in patients with IPF and chronic cough.[41] In contrast, PA101 has been displayed to yield encouraging anti-tussive outcomes in patients with IPF and chronic cough, but not in patients with idiopathic chronic cough.[42] These findings suggest that the cough mechanism in patients with IPF is disease-specific, and the anti-tussive efficacy of gefapixant and PA101 varies substantially depending on the underlying etiology of chronic cough.

At the present time, global, large-scale, and phase III trials are in progress to investigate the effect of gefapixant (15 mg and 45 mg b. i. d.) in more than 2000 patients with chronic cough.[43] Table 4 displays a list of registered but not published clinical trials about gefapixant in the management of patients with chronic cough. Furthermore, other extremely selective P2X3 antagonists (BLU-5937, BAY1817080, and S-600918) are also under investigation for pharmacokientics, pharmacodynamics, safety, and efficacy in early phase clinical trials [Table 5].

Table 4.

A list of registered but not published clinical trials (clinicaltrials.gov) about gefapixant in the management of patients with chronic cough

| NCT ClinicalTrials.gov | Study phase | Study title | Current status |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04193176 | Phase 3 | A Phase 3b Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo Controlled, Multicenter Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Gefapixant in Women with Chronic Cough and Stress Urinary Incontinence | Recruiting |

| NCT04193202 | Phase 3 | A Phase 3b Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo Controlled, Multicenter Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Gefapixant in Adult Participants with Recent Onset Chronic Cough | Recruiting |

| NCT03696108 | Phase 3 | A Phase 3, Randomized, Double-blind Clinical Study to Evaluate the Long-term Safety and Efficacy of MK-7264 in Japanese Adult Participants with Refractory or Unexplained Chronic Cough | Active, not recruiting |

| NCT03482713 | Phase 2 | Phase II Study, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled 4-Week Clinical Study, to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of MK-7264 in Adult Japanese Participants with Unexplained or Refractory Chronic Cough | Completed, has results |

| NCT02397460 | Phase 2 | A Study to Assess the Effect of AF-219 on Cough Reflex Sensitivity in Both Healthy and Chronic Cough Subjects | Completed |

| NCT03449147 | Phase 3 | A Phase 3, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, 12-Month Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of MK-7264 in Adult Participants with Chronic Cough (PN030) | Active, not recruiting |

| NCT03449134 | Phase 3 | A Phase 3, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, 12-Month Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of MK-7264 in Adult Participants with Chronic Cough (PN027) | Active, not recruiting |

| NCT02612623 | Phase 2 | A Randomized, Parallel, Double-Blind Study to Assess the Efficacy and Tolerability of AF-219 in Subjects with Refractory Chronic Cough | Completed, has results |

NCT=National Clinical Trial

Table 5.

A list of registered clinical trials (clinicaltrials.gov) about selective P2X3 antagonists (BLU-5937, BAY1817080 and S-600918) which are under development and testing in healthy individuals and patients with chronic cough

| NCT ClinicalTrials.gov | Study phase | Study title | Current status |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCT03979638 | Phase 2 | A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover, dose escalation study of BLU-5937 in subjects with unexplained or Refractory Chronic Cough (RELIEF) | Terminated, due to the impact of the COVID-19 on trial activities |

| NCT03638180 | Phase 1 | A double-blind, placebo controlled, randomized, adaptive, first-in-human study to assess, safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and food effect of single and multiple doses of BLU-5937 administered orally in healthy male and female | Completed |

| NCT04471337 | Phase 1 | An open-label study to evaluate the Pharmacokinetics and Safety of BAY 1817080 in participants with impaired renal function in comparison to matched controls with normal renal function | Recruiting |

| NCT04487431 | Phase 1 | Single-center, Open-label, Nonplacebo-controlled, Single-dose Study in Healthy Male Participants to Determine the Pharmacokinetics of BAY 1817080 Oral Solution (Part A) and to Investigate the Pharmacokinetics, Metabolic Disposition and Mass Balance of [14C] BAY 1817080 Oral Solution (Part B) | Recruiting |

| NCT04265781 | Phase 1 | Phase 1 Dose escalation study to investigate safety, tolerability and harmacokinetics of single and multiple doses of BAY 1817080 in Japanese Healthy Adult Male Participants in a single-center, randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled design | Recruiting |

| NCT04454424 | Phase 1 | An open-label study to evaluate the pharmacokinetics, safety and tolerability of BAY 1817080 in participants with Impaired Hepatic Function (Classified as Child-Pugh A, B or C) in comparison to matched controls with normal hepatic function | Recruiting |

| NCT03773068 | Phase 1 | Open label, partially randomized, cross-over study to determine the absolute bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of BAY1817080 using a Simultaneous Anticipated Therapeutic Oral Dose Along with an i.v. [13C715N]-Labeled Microtracer and to investigate the relative bioavailability of two formulations given under different diets at 2 dose levels in healthy volunteers | Completed |

| NCT04423744 | Phase 1 | Randomized, single-blind, double-dummy, 4-fold Cross-over, Placebo- and active-controlled study to investigate the influence of BAY 1817080 on the QTc Interval in healthy male and female participants (TQT Study) | Recruiting |

| NCT04252300 | Phase 1 | Open label, fixed sequences, one-way cross-over study to determine the effects of multiple doses BAY 1817080 (150 mg) on the Pharmacokinetics of a 5 mg Dose Rosuvastatin in healthy participants | Active, not recruiting |

| NCT02817100 | Phase 1 | Randomized, Placebo-controlled, Double-blind, Parallel Group Study to Investigate the Safety, Tolerability and Pharmacokinetics of Increasing Single Oral Doses (10-1500 mg, tablets) of BAY 1817080 Including the Effect of Food and Itraconazole on the Relative Bioavailability of BAY1817080 in Healthy Men | Completed |

| NCT03310645 | Phase 1 | Two-part, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, parallel-group Study: (Part 1) in healthy male volunteers to assess safety and tolerability of ascending repeated oral doses of BAY1817080, Followed by (Part 2), Two-way crossover administration of four different doses in patients with refractory chronic cough to assess safety, tolerability, and efficacy for Proof of Concept | Completed |

| NCT04110054 | Phase 2 | A Phase 2b, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, Parallel-group, Dose-selection Study of S-600918 in Patients with Refractory Chronic Cough | Recruiting |

NCT=National Clinical Trial

Our study has several strengths. Most importantly, this is the first meta-analysis that pooled the therapeutic efficacy and safety of gefapixant in the treatment of chronic cough. Moreover, we estimated all potential reported outcomes, solved the heterogeneity, performed sub-group analyses, and used more than one software for statistical computations. Nevertheless, our study is not without limitations. The major limitation of this study is the relatively small number of included trials with two of them from the same study and their respective small sample size. In addition, the included studies varied significantly with regard to the drug doses. The standard range for medication dosing is yet to be determined. This might have negatively impacted the heterogeneity in our study and influenced the study outcomes in terms of drug efficacy and side effects. To elaborate, Smith et al. S1[25] reported gefapixant outcomes at doses of 50 mg, 100 mg, 150 mg, and 200 mg. Smith et al. S2[25] reported gefapixant outcomes at doses of 7.5 mg, 15 mg, 30 mg, and 50 mg. Smith et al. S3[26] reported gefapixant outcomes at doses of 7.5 mg, 20 mg, and 50 mg. Morice et al.[27] reported gefapixant outcomes at a single dose of 100 mg. Finally, Abdulqawi et al.[24] reported gefapixant outcomes at a single dose of 600 mg. We pooled outcomes at sub-group analyses at doses of 7.5 mg, 50 mg, and 100 mg only. This is because these doses were reported in more than one trial.

Conclusions

Based on our systematic review and meta-analysis, we conclude that gefapixant is a novel promising therapy in the management of patients with chronic cough. Specifically, gefapixant exhibits favorable anti-tussive outcomes by improving the cough frequency, severity, and quality of life. While gefapixant is largely tolerable, its side effects (notably taste alteration) are dose dependent. Well-established RCTs with large sample sizes are highly recommended to further consolidate the reported safety and efficacy outcomes of gefapixant in patients with chronic cough.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary File 1

Forest plot (a) and meta-regression analysis (b) demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding any adverse event

Forest plot (a) and meta-regression analysis (b) demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding adverse events related to treatment

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding discontinuation due to adverse events

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding serious adverse events

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding dysgeusia

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding hypogeusia

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding ageusia

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding headache

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding upper respiratory tract infection

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding cough

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding nausea

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding urinary tract infection

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding renal or urological events

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding oral paraesthesia

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding oral hypoesthesia

References

- 1.Finley CR, Chan DS, Garrison S, Korownyk C, Kolber MR, Campbell S, et al. What are the most common conditions in primary care? Systematic review. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64:832–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Çolak Y, Nordestgaard BG, Laursen LC, Afzal S, Lange P, Dahl M. Risk factors for chronic cough among 14,669 individuals from the general population. Chest. 2017;152:563–73. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song WJ, Chang YS, Faruqi S, Kim JY, Kang MG, Kim S, et al. The global epidemiology of chronic cough in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:1479–81. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00218714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford AC, Forman D, Moayyedi P, Morice AH. Cough in the community: A cross sectional survey and the relationship to gastrointestinal symptoms. Thorax. 2006;61:975–9. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.060087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung KF, Pavord ID. Prevalence, pathogenesis, and causes of chronic cough. Lancet. 2008;371:1364–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGarvey L, McKeagney P, Polley L, MacMahon J, Costello RW. Are there clinical features of a sensitized cough reflex. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2009;22:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young EC, Brammer C, Owen E, Brown N, Lowe J, Johnson C, et al. The effect of mindfulness meditation on cough reflex sensitivity. Thorax. 2009;64:993–8. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.116723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singapuri A, McKenna S, Brightling CE. The utility of the mannitol challenge in the assessment of chronic cough: A pilot study. Cough. 2008;4:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hilton EC, Baverel PG, Woodcock A, van Der Graaf PH, Smith JA. Pharmacodynamic modeling of cough responses to capsaicin inhalation calls into question the utility of the C5 end point. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:847–550. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.04.042. e1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibson PG, Vertigan AE. Management of chronic refractory cough. BMJ. 2015;351:h5590. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h5590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryan NM, Vertigan AE, Birring SS. An update and systematic review on drug therapies for the treatment of refractory chronic cough. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2018;19:687–711. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2018.1462795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irwin RS, Baumann MH, Bolser DC, Boulet LP, Braman SS, Brightling CE, et al. Diagnosis and management of cough executive summary: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129:1S–23. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.1S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morice AH, Millqvist E, Belvisi MG, Bieksiene K, Birring SS, Chung KF, et al. Expert opinion on the cough hypersensitivity syndrome in respiratory medicine. Eur Respir J. 2014;44:1132–48. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00218613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morice AH, Menon MS, Mulrennan SA, Everett CF, Wright C, Jackson J, et al. Opiate therapy in chronic cough. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:312–5. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-892OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeyakumar A, Brickman TM, Haben M. Effectiveness of amitriptyline versus cough suppressants in the treatment of chronic cough resulting from postviral vagal neuropathy. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:2108–12. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000244377.60334.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canning BJ, Chou YL. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg; 2009. Cough sensors. I. Physiological and pharmacological properties of the afferent nerves regulating cough InPharmacology and Therapeutics of Cough; pp. 23–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vulchanova L, Riedl MS, Shuster SJ, Buell G, Surprenant A, North RA, et al. Immunohistochemical study of the P2X2 and P2X3 receptor subunits in rat and monkey sensory neurons and their central terminals. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1229–42. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burnstock G, Brouns I, Adriaensen D, Timmermans JP. Purinergic signaling in the airways. Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64:834–68. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.005389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weigand LA, Ford AP, Undem BJ. A role for ATP in bronchoconstriction-induced activation of guinea pig vagal intrapulmonary C-fibres. J Physiol. 2012;590:4109–20. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.233460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwong K, Kollarik M, Nassenstein C, Ru F, Undem BJ. P2X2 receptors differentiate placodal vs. neural crest C-fiber phenotypes innervating guinea pig lungs and esophagus. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L858–65. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90360.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamei J, Takahashi Y, Yoshikawa Y, Saitoh A. Involvement of P2X receptor subtypes in ATP-induced enhancement of the cough reflex sensitivity. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;528:158–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamei J, Takahashi Y. Involvement of ionotropic purinergic receptors in the histamine-induced enhancement of the cough reflex sensitivity in guinea pigs. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;547:160–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khakh BS, North RA. P2X receptors as cell-surface ATP sensors in health and disease. Nature. 2006;442:527–32. doi: 10.1038/nature04886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdulqawi R, Dockry R, Holt K, Layton G, McCarthy BG, Ford AP, et al. P2X3 receptor antagonist (AF-219) in refractory chronic cough: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet. 2015;385:1198–205. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith JA, Kitt MM, Butera P, Smith SA, Li Y, Xu ZJ, et al. Gefapixant in two randomised dose-escalation studies in chronic cough. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:1901615. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01615-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith JA, Kitt MM, Morice AH, Birring SS, McGarvey LP, Sher MR, et al. Gefapixant, a P2X3 receptor antagonist, for the treatment of refractory or unexplained chronic cough: A randomised, double-blind, controlled, parallel-group, phase 2b trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;2600:1–11. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30471-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morice AH, Kitt MM, Ford AP, Tershakovec AM, Wu WC, Brindle K, et al. The effect of gefapixant, a P2X3 antagonist, on cough reflex sensitivity: A randomised placebo-controlled study. Eur Respir J. 2019;54:1900439. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00439-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins JP, Green S. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2008. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;349:1–25. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haque RA, Usmani OS, Barnes PJ. Chronic idiopathic cough: A discrete clinical entity. Chest. 2005;127:1710–3. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gibson P, Wang G, McGarvey L, Vertigan AE, Altman KW, Birring SS, et al. Treatment of unexplained chronic cough: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2016;149:27–44. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Irwin RS, Boulet LP, Cloutier MM, Fuller R, Gold PM, Hoffstein V, et al. Managing cough as a defense mechanism and as a symptom. A consensus panel report of the American College of Chest Physicians. Chest. 1998;114:133S–181. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.2_supplement.133s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryan NM, Gibson PG. Characterization of laryngeal dysfunction in chronic persistent cough. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:640–5. doi: 10.1002/lary.20114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chung KF. Approach to chronic cough: The neuropathic basis for cough hypersensitivity syndrome. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6:S699–707. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.08.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Canning BJ, Chang AB, Bolser DC, Smith JA, Mazzone SB, McGarvey L, et al. Anatomy and neurophysiology of cough: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel report. Chest. 2014;146:1633–48. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Groneberg DA, Niimi A, Dinh QT, Cosio B, Hew M, Fischer A, et al. Increased expression of transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 in airway nerves of chronic cough. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:1276–80. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-174OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chung KF. Advances in mechanisms and management of chronic cough: The Ninth London International Cough Symposium 2016. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2017;47:2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Song WJ, Chung KF. Pharmacotherapeutic options for chronic refractory cough. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2020;21:1–14. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2020.1751816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garceau D, Chauret N. BLU-5937: A selective P2X3 antagonist with potent anti-tussive effect and no taste alteration. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2019;56:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Obrecht AS, Urban N, Schaefer M, Röse A, Kless A, Meents JE, et al. Identification of aurintricarboxylic acid as a potent allosteric antagonist of P2X1 and P2X3 receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2019;158:107749. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.107749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martinez FJ, Afzal A, Kitt MM, Ford A, Li JJ, Li Y-P, et al. The treatment of chronic cough in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients with gefapixant, a P2×3 receptor antagonist. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:A2638. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Birring SS, Wijsenbeek MS, Agrawal S, van den Berg JW, Stone H, Maher TM, et al. A novel formulation of inhaled sodium cromoglicate (PA101) in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and chronic cough: A randomised, double-blind, proof-of-concept, phase 2 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5:806–15. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30310-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muccino D, Green S. Update on the clinical development of gefapixant, a P2X3 receptor antagonist for the treatment of refractory chronic cough. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2019;56:75–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2019.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Forest plot (a) and meta-regression analysis (b) demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding any adverse event

Forest plot (a) and meta-regression analysis (b) demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding adverse events related to treatment

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding discontinuation due to adverse events

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding serious adverse events

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding dysgeusia

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding hypogeusia

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding ageusia

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding headache

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding upper respiratory tract infection

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding cough

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding nausea

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding urinary tract infection

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding renal or urological events

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding oral paraesthesia

Forest plot demonstrating the overall effect estimate between gefapixant and placebo groups regarding oral hypoesthesia