A 56‐year‐old man with a history of endoscopically confirmed gastroesophageal reflux disease came to his primary care physician complaining of nonexertional substernal and upper midepigastric discomfort somewhat different from his usual reflux symptomatology. Blood pressure (BP), which 3 months previously had been 124/64 mm Hg, was 186/112 mm Hg. His only medication was over‐the‐counter cimetidine, and he had never been hospitalized. He had smoked one pack of cigarettes daily for almost 40 years. Atenolol was initiated and a follow‐up dual isotope cardiac scan with exercise showed no evidence of ischemia. His discomfort subsided with omeprazole; it was attributed to acid reflux. Clinic follow‐up revealed persistent hypertension and BPs on atenolol and captopril were 162–166 mm Hg/100‐102 mm Hg. Laboratory data revealed a hemoglobin of 15 g/dL (14–18 g/dL), blood urea nitrogen 20 mg/dL (<19 mg/dL), creatinine 0.7 mg/dL (0.7–1.3 mg/dL), potassium 4.1 mEquation (3.5–5.0 mEq), total cholesterol 194 mg/dL (<200 mg/dL), calcium 9.4 mg % (8.5–10.7 mg %), and 3+ protein on spot urinalysis without any white or red blood cells.

To further evaluate the proteinuria, a renal ultrasound was performed. This study revealed a hypoechoic left renal mass measuring 9.4 cm in greatest dimension along with a 6.9 cm right renal cyst. Corresponding to the hypoechoic left renal mass, a computed tomography scan showed an oval well‐circumscribed 6.0 cm × 8.0 cm cortically based mass involving the anterolateral cortex of the left renal mid zone (Figure). The mass was solid and demonstrated heterogeneous enhancement. It was felt to be compatible with a renal cell carcinoma. A left radical nephrectomy was performed and the gross pathology showed the mass to extend up to, but not through, the renal capsule. Microscopic pathology (Figure) demonstrated a low nuclear‐grade, clear cell‐type renal cell carcinoma with maximum tumor dimensions of 5.6 × 6.3 × 5.8 cm. The surgical margins were clear of carcinoma and there was no involvement of the left renal vein, perinephric adipose tissue, or surrounding lymph nodes. The patient made a good postoperative recovery and follow‐up BPs for 6 months were 120–136 mm Hg/80–86 mm Hg off all antihypertensive medication.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography revealing a circumscribed solid heterogeneous 6×8 cm anterolateral midleft kidney mass adjoining normal kidney

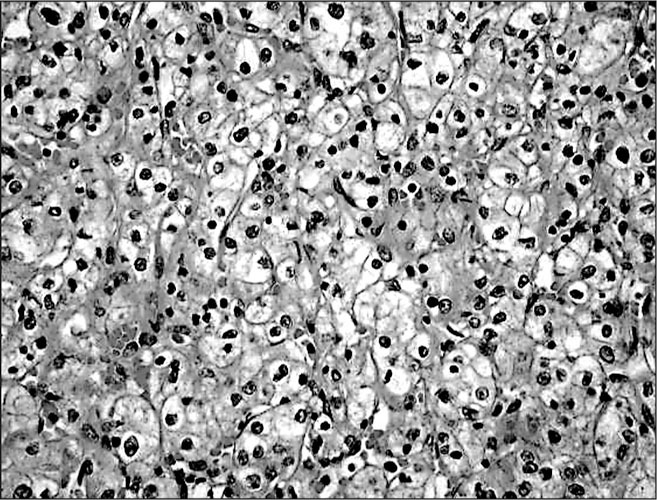

Figure 2.

High‐power view showing a low nuclear‐grade clear cell‐type renal cell carcinoma

DISCUSSION

The spectrum of association of hypertension with renal cell carcinoma includes essential hypertension as a risk factor for renal cell carcinoma and secondary hypertension as a paraneoplastic phenomenon. Essential hypertension, as well as obesity and cigarette smoking, are well defined, independent risk factors for renal cell carcinoma. 1 In a survey of 363,992 Swedish male construction workers followed in a nationwide cancer registry from 1971 to 1992, 759 were found to have renal cell carcinoma. 1 Chow et al. were able to show a significant renal cell cancer relationship according to the severity of both systolic (p=0.007) and diastolic (p<0.001) hypertension. 1 The risk of renal cell carcinoma was proportionate to the average systolic or diastolic BP preceding the discovery of cancer.

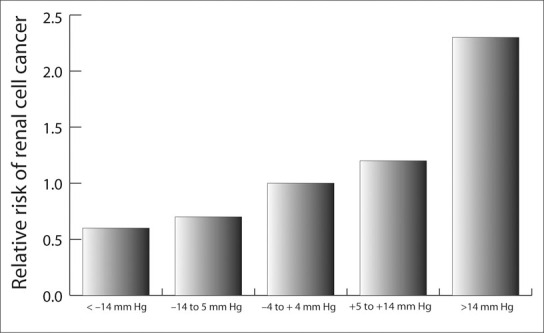

Interestingly, over 6 years of follow‐up past the baseline physical examination in this Swedish study, BP reductions in response to treatment were associated with a reduced cancer risk (Figure). Renal cell carcinoma risk more than doubled in men whose diastolic pressure rose by more than 14 mm Hg, compared with construction workers whose diastolic pressure was unchanged; however, a reduction in diastolic pressure by 14 mm Hg reduced the risk by 40%. Therefore, the authors suggested that treatment of hypertension might help to prevent renal cell carcinoma. Whereas the possible association of diuretic therapy with renal cell cancer has been raised, 2 other epidemiological studies have shown that it is not possible to distinguish this risk from that of essential hypertension alone. 1 , 3

Figure 3.

Relative risk of renal cell cancer related to diastolic blood pressure change in the first 6 years of follow‐up. Trend (p<0.0010); number of men=110,255; person‐years of follow‐up=l,451,488. Adapted with permission from Chow WH, et al. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1305–1311. 1

Renal cell carcinoma may also be associated with a range of paraneoplastic manifestations of which hypertension may be a particularly common entity, occurring in 20%–40% of all cases 4 ; however, the prevalence of essential hypertension is such that many of these cases may be confounded by a simple association rather than causality. 5 The association of hypertension and renal tumors was first described in 1938 for nephroblastoma (Wilm's tumor) and in 1940 for renal cell carcinoma. 6 , 7 Renal cell carcinoma, Wilm's tumors, juxtaglomerular cell tumors, and benign renal hemangiopericytomas, which usually occur in younger people, constitute a group of renin‐secreting renal tumors causing reversible hypertension. 5 A variety of pathophysiologic mechanisms have been suggested including enhanced renin production, vasculitis, polycythemia induced by excess erythropoietin, hypercalcemia possibly associated with ectopic prostaglandin, renal arteriovenous fistula, ureteral obstruction, ectopic production of noradrenaline, and Cushing's syndrome with ectopic glucocorticoid production. 4 , 5 von Hippel‐Lindau syndrome is a defect of chromosome 3 causing cerebellar and retinal hemangioblastomas, and the constellation of this syndrome may include renal cell carcinoma in two thirds of patients 5 together with pheochromocytoma. More recent research has demonstrated that most renal cell carcinomas are caused by biallelic loss of the von Hippel‐Lindau gene, which causes up‐regulation of endothelial growth factor. Renal cell carcinoma‐associated endothelial growth factor is a potent angiogenesis agent which has been used as a target for monoclonal antibody therapy for patients with metastatic disease in exploratory studies. 8 Neoplastic and paraneoplastic mechanisms and associations with renal cell carcinoma and hypertension are listed in the Table.

As a paraneoplastic manifestation, it appears that very high BP elevations and malignant hypertension are more likely to occur. 9 , 10 In a Birmingham, England hospital study, 192 consecutive patients with renal cell carcinoma were matched with 254 patients with malignant hypertension recorded in hospital records over 21 years. 10 Though only 81% of the patients with malignant hypertension underwent renal imaging, three of 254 individuals with malignant hypertension had renal carcinoma. This prevalence of 1.2% exceeded the age‐related prevalence of renal cell carcinoma in England and Wales, which was estimated at 0.01%. On the basis of these observations, renal imaging for patients hospitalized with malignant hypertension is recommended.

The patient under discussion had long‐term cigarette smoking and obesity as risk factors for renal cell carcinoma, but his hypertension appeared to be of relatively acute onset and responded to nephrectomy. Though renal structural abnormalities were ruled out by imaging studies and laboratory tests also removed the possible etiologies of erythrocytosis and hypercalcemia, a work‐up to assess the possibilities of excess renin secretion or ectopic noradrenaline was not undertaken. Nonetheless, the probability of hypertension as a paraneoplastic presentation was considered likely.

References

- 1. Chow WH, Gridley G, Fraumeni JF, et al. Obesity, hypertension, and the risk of kidney cancer in men. N Engl J Med. 2000; 343: 1305–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Messerli FH. Diuretic therapy and renal cell carcinomaanother controversy? Eur Heart J. 1999; 20: 1441–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yuan JM, Castelao JE, Gago‐Dominguez M, et al. Hypertension, obesity, and their medications in relation to renal cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 1998; 77: 1508–1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thomas MC, Walker RJ, Kankatsu Y. cc. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998; 13: 1811–1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cronin RE, Kaehny WD, Miller PD, et al. Renal cell carcinoma: unusual systemic manifestations. Medicine. (Baltimore). 1976; 55: 291–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bradley JE, Pincoffs MC. The association of adeno‐myosarcoma of the kidney (Wilms tumor) with arterial hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 1938; 11: 1613–1628. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Horton BT. The relationship of hypertension to renal neoplasm. Proc Mayo Clin. 1940; 15: 472–474. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang JC. Bevacizumab for patients with metastatic renal cancer: an update. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(18 pt 2):6367S–6370S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moein MR, Dehghani VO. Hypertension: a rare presentation of renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2000;164:2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wong PSC, Lip GYH, Gearty JC, et al. Renal cell carcinoma and malignant phase hypertension. Blood Press. 2001; 10: 16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]