Abstract

Much debate surrounds the question of the optimal therapeutic choices for medication to control blood pressure and reduce cardiovascular events. Experimental evidence suggests that drugs that block the renin‐angiotensin system retard vascular disease through their direct ability to antagonize the effects of angiotensin II, which has vasoconstrictive, vascular proliferative, and atherosclerotic effects. It is not known how to separate the potential vascular protective effects of the drugs from their antihypertensive benefits. Clinical trial evidence indicates that achieved lower blood pressure goals almost always confer cardiovascular risk reduction advantages. There is also evidence, however, that successful antihypertensive regimens incorporating a renin‐angiotensin system blocker, such as an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker, provide more cardiovascular risk reduction benefit compared with regimens that do not incorporate a renin‐angiotensin blocker. This includes composite or specific end points involving reduction of stroke, myocardial infarction, or development of end‐stage renal disease.

In addition to the current debate as to the optimal blood pressure (BP) for preventing cardiovascular (CV) events, another important debate is whether certain antihypertensive medications confer a CV or renal disease risk reduction advantage compared with other drugs, independent of BP effects.

The Framingham Heart Study 1 provides important evidence that for patients over the age of 50 years, controlling systolic BP to below 140 mm Hg should be an important focus. For many patients—particularly those who have some evidence of renal insufficiency, with an estimated glomerular filtration rate below 60 mL/min, or diabetes—current guidelines recommend systolic BP goals below 130 mm Hg. 2 These lower recommended systolic BP goals for many patients may be difficult to achieve because of the effects of obesity and some resistance to the effects of antihypertensive medication. Consequently, most patients need two or more medications to achieve BP goals. Thus, the current debate should be focused on identifying the optimal antihypertensive regimens for achieving safe and effective long‐term BP control that also may provide optimal reduction of CV events.

The renin‐angiotensin system (RAS) blockers, both angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), may provide more than just the benefit of BP reduction. 3 , 4 Experimental evidence indicates that there may be a therapeutic advantage to antagonizing the effects of angiotensin II on CV tissues throughout the body. 3 , 4 Not only is angiotensin II a potent vasoconstrictor and a hormone that enhances renal sodium and water retention, but it also has vascular proliferative actions and causes oxidative stress, inhibits endothelial function, and stimulates soluble mediators of scarring and fibrosis that may lead to changes in blood vessels and target organs. These changes can affect BP and lead to progressive target organ dysfunction.

The relationship between the RAS and vascular disease is an intriguing one. On the one hand, the system has evolved as one of the more important systems in regulating BP homeostasis through its neurohormonal effects. On the other hand, it is pivotally involved in the regulation of vascular injury and repair responses. 4 Higher levels of arterial pressure create more mechanical stretch and strain in the circulation and result in localized areas of turbulence. These injuries, if recurrent, result in a progressive remodeling and restructuring disease process which leads to conformational changes in the blood vessels. From a theoretic standpoint, it would make sense to facilitate both better BP reduction and targeting the RAS as a means of limiting vascular and consequent target organ injury. The separation of the antiproliferative effects of blocking angiotensin II with RAS blockers from the BP‐lowering benefits is not possible. One can, however, review the evidence of the benefits of BP reduction with different forms of antihypertensive drug therapy from clinical trials in people with heart and kidney disease to gain an appropriate perspective. This report will focus on the key message from these trials: lower BP and block the RAS!

WHAT IS TARGET ORGAN PROTECTION?

The definition of target organ protection varies substantially among clinical trials. Some studies focus specifically on CV risk reduction measures, whereas others may look directly at preventing the progression of kidney disease or the development of end‐stage renal disease. Still others address issues related to reduction in the incidence of stroke. The ultimate measure, irrefutable and easy to define, is death, or a composite of lethal events linked to CV disease. Many of the studies are designed to show a statistical difference among therapies. Most trials, however, are of 4–5 years' duration. One may question whether there is sufficient time in these short‐term studies to develop sufficient end points to distinguish among therapeutic approaches and BP goals. A 4–5‐year clinical trial is a short window of exposure.

Often, surrogate measures of therapeutic success are considered when the differences in definitive CV end points or primary end points are not always discernible. Some trials measure reduction of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) or albuminuria; others include diminished likelihood of developing congestive heart failure or diabetes mellitus during the 5‐year follow‐up. It is important to note that these are intriguing measures, yet they have never been substantiated in prospective clinical trials as measures of successful prevention of either CV or renal end points. Despite the lack of evidence based on prospective clinical trials, there is consistent evidence from post hoc analyses of many large studies that indicates that regression of LVH, 5 reduction of albuminuria, 6 , 7 , 8 and reduction in the incidence of diabetes or heart failure may be associated with fewer CV end points. 9 Admittedly, this evidence is not as solid as primary evidence from blinded, randomized, prospective trials.

In evaluating both definitive end points and surrogate measures in the various trials, it should be noted that the reduction of BP remains consistently the most important measure of better target organ protection. 10 , 11 The consistency of this observation need not be debated. The real question, then, is does blocking the RAS provide an incremental advantage in addition to achieving an appropriate BP goal?

CV END POINT TRIALS

Five of the most recent antihypertensive studies utilized multiple drug regimens to control BP, with at least one treatment regimen incorporating an RAS blocker, compared with a regimen not containing an RAS blocker.

The Heart Outcomes Protection Evaluation (HOPE) 12 examined the 4–5‐year outcomes of more than 9000 66‐year‐old patients with extensive CV disease (80% with coronary disease, 38% with diabetes, 11% with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack). These patients were randomized to receive either an ACE inhibitor (ramipril 10 mg) or a placebo in addition to their existing medical regimen, which often included two or three other medications. The primary outcome of the trial was a composite of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, or death from CV causes. Most of the patients in the study were on antihypertensive medications before randomization. These included calcium channel blockers (CCBs) (46%–48%), β blockers (39%–40%), and diuretics (approximately 15%). Mean BP at the time of randomization was 139/79 mm Hg. The patients receiving the ACE inhibitor experienced a 3–10 mm Hg reduction in systolic BP during the course of follow‐up, depending on whether casual BP measurement or ambulatory BP monitoring was used. 13 The study reported that patients in the RAS‐blocking arm, who also had lower BP, experienced a statistically significant reduction in the risk of the composite end point of MI, stroke, or CV death (Table I). Whether this was related to greater BP reduction or RAS inhibition, or both, cannot be answered. The results of this study suggest that it would be optimal to do both. There were, moreover, important surrogate measures of advantage in the ACE inhibitor treatment arm, with less progression of albuminuria, less new‐onset diabetes, and less congestive heart failure.

Table I.

Heart Outcomes Protection Evaluation: Risk Reductions for Patients on ACEI + Other Medications vs. No ACEI

| Outcomes | Risk Reduction (%) |

|---|---|

| Myocardial infarction, stroke, cardiovascular death | 22 |

| Cardiovascular death | 25 |

| Myocardial infarction | 20 |

| Stroke | 31 |

| Revascularization procedures* | 16 |

| New‐onset diabetes | 32 |

| ACEI=angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; *revascularization procedures included percutaneous coronary angioplasty, coronary artery bypass grafting, or peripheral angioplasty. Adapted from N Engl J Med. 2000;342:145–153. 12 | |

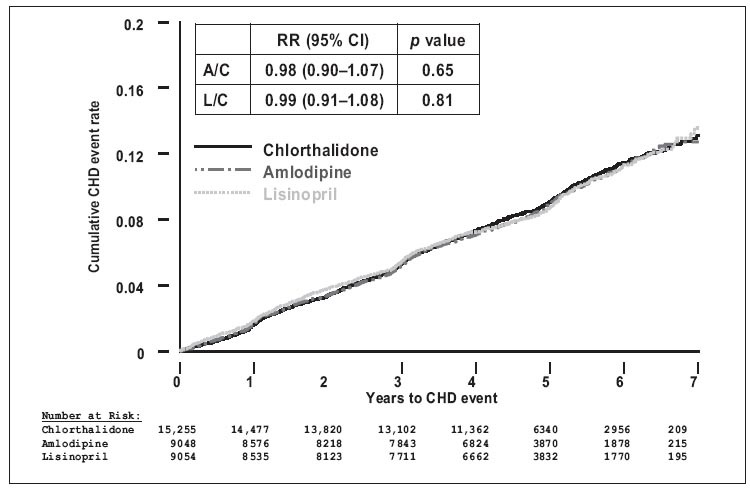

In the Antihypertensive and Lipid Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT), 14 over 35,000 patients were randomized into a three‐arm trial (after the doxazosin arm was terminated) to evaluate the efficacy of various antihypertensive medications in lowering BP and preventing CV events. 14 The majority of the patients were treated hypertensives who, when taking their medication, had a BP of approximately 145/83 mm Hg. They were then randomized to receive chlorthalidone, amlodipine, or lisinopril, each of which could be titrated to an appropriate dose, plus other medications to achieve a BP <140/90 mm Hg. The primary measure of outcome over the course of 5 years was fatal or nonfatal MI. Participants in the ALLHAT trial were virtually the same age (67 years) as the participants in the HOPE study (66 years). ALLHAT had more ethnic minority representation, whereas there were very few minorities in the HOPE study. Approximately 36% of the patients had diabetes (nearly the same as HOPE), but far fewer had a history of CV disease (25%). The mean number of drugs used to control BP in the ALLHAT participants was two. Unlike the HOPE study, where the RAS‐blocking regimen had a 3–10 mm Hg systolic BP advantage, in the ALLHAT trial the ACE inhibitor (lisinopril) arm had a 2–3 mm Hg systolic BP disadvantage compared with the diuretic group during the course of follow‐up. Despite this difference, the cumulative event rates for the primary outcome were not different (Figure 1). There were fewer strokes in the chlorthalidone‐treated patients compared with the ACE inhibitor patients, but the ACE inhibitor arm had a BP disadvantage. With regard to surrogate measures, there was less heart failure with the diuretic, compared with the CCB‐ and ACE inhibitor‐based regimens, but less new‐onset diabetes in the ACE inhibitor arm compared with the other two. Thus, this study suggests that the use of a diuretic‐based regimen results in a favorable outcome but an ACE inhibitor‐based regimen may have some advantages, such as less new‐onset diabetes, if BP lowering can be achieved—usually with two or more medications.

Figure 1.

Results of the Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT): no difference in primary outcome among the three regimens. RR=relative risk; Cl=confidence interval; A=amlodipine; C=chlorthalidone; L=lisinopril; CHD=coronary heart disease. Adapted with permission from JAMA. 2002;288:2981–2997. 14

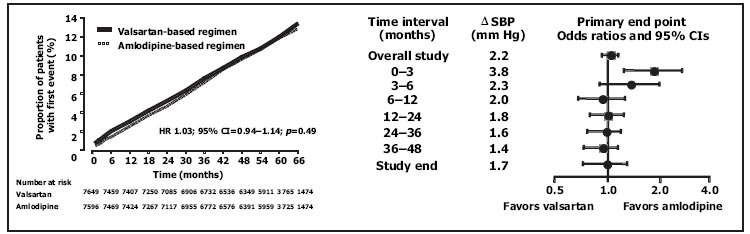

The Valsartan Antihypertensive Long‐term Use Evaluation (VALUE) 15 evaluated an ARB (valsartan)‐based regimen compared with a CCB (amlodipine)‐based regimen over the course of 5 years in more than 15,000 hypertensives. 15 All patients received thiazide diuretics or other add‐on medications as needed to control BP to <140/90 mm Hg. The mean age of the participants, as in HOPE and ALLHAT, was 67 years. Approximately 33% had diabetes and 45%–46% had coronary artery disease. During the course of follow‐up, the RAS‐blocking regimen with valsartan (2–4 mm Hg difference) was less effective in lowering BP than the CCB‐based regimen with amlodipine. Despite this, there was no difference in the primary composite cardiac end point (Figure 2). There was, however, evidence that early control of BP with the CCB‐based regimen provided an important CV risk reduction advantage for the first 3–6 months. When comparing surrogate measures of outcome, there were fewer patients in the valsartan regimen who developed heart failure or death from heart failure (p=0.12), compared with the amlodipine regimen. There was also a 23% reduction in the risk of new diabetes in the ARB arm compared with the CCB arm. The results of this study, like the ALLHAT study, suggest that the majority of hypertensive patients need two or more therapies. There may be a good reason to include a medication that blocks the RAS in the treatment regimen.

Figure 2.

Results of the Valsartan Antihypertensive Long‐term Use Evaluation (VALUE): fewer events within the first year or so in amlodipine groups with lower blood pressures (Bps); no overall difference at end of study. HR=hazard ratio; CI=confidence interval; ΔSBP=difference in systolic BP between groups. Reproduced with permission from Lancet. 2004;363:2022–2031. 15

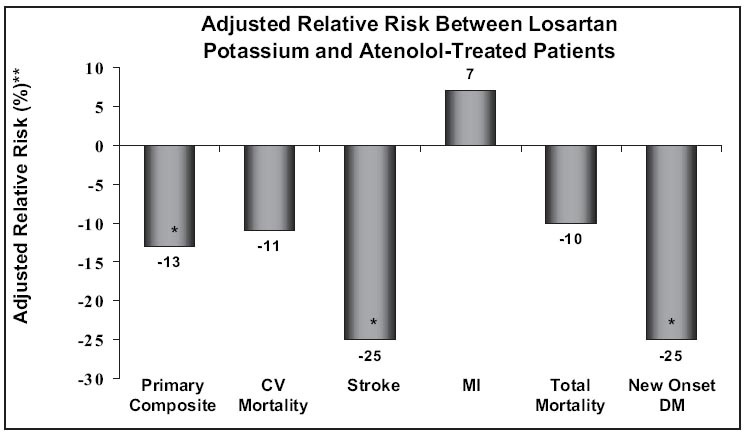

The Losartan Intervention for End Point Reduction in Hypertension (LIFE) study 5 evaluated the effects of two different antihypertensive regimens in more than 9000 people between the ages of 55 and 80 years who had hypertension and LVH. Patients were randomized to receive either an ARB‐based regimen (losartan) or a β‐blocker‐based regimen (atenolol). The primary end point was CV morbidity/mortality. During the course of follow‐up, despite a nearly identical reduction of BP, there was a 13% reduction in the risk of the primary CV composite end point in the losartan regimen (Figure 3). Most of this advantage, however, was related to a 25% reduction in the risk of stroke. Surrogate measures of CV benefits were also more consistently noted in the RAS‐blocking arm, with more reduction of LVH and a 25% reduction in the incidence of new‐onset diabetes. Patients who experienced a reduction of albuminuria (more common in the losartan arm) experienced fewer CV events. For patients with hypertension and LVH, this study suggests that there may be a benefit to blocking the RAS—in this case, with an ARB.

Figure 3.

The Losartan Intervention for End Point Reduction in Hypertension (LIFE) study. New‐onset diabetes and stroke were significantly lower in angiotensin receptor blocker‐treated compared with β‐blocker‐treated patients; primary composite was also lower, primarily due to stroke difference. CV=cardiovascular; MI=myocardial infarction; DM=diabetes mellitus; *p<0.05; **values adjusted for difference in achieved blood pressure and left ventricular hypertrophy. Adapted with permission from Lancet. 2002;359:995–1003. 5

In March 2005, the results of a large, northern European study were reported to the American College of Cardiology. The Anglo‐Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial (ASCOT) 16 randomized more than 19,000 people with high BP to receive two different therapeutic regimens incorporating either atenolol, 50–100 mg, with bendroflumethiazide, 1.25–2.5 mg, or amlodipine, 5–10 mg, plus perindopril, 4–8 mg, for a period of 5 years. There was also a lipid‐lowering arm. 16 All patients had to have three or more additional CV risk factors in addition to their high BP. The primary end point was nonfatal MI and fatal coronary heart disease. There was no difference in primary outcome between the two groups. The trial was terminated 2 years early, however, due to significant overall CV benefits in the amlodipine/perindopril arm. This regimen also had a mean BP advantage of 2.9/1.8 mm Hg for the first few years of the study. Not surprisingly, there was an associated reduction of 25% in CV mortality, and a 30% reduction in the incidence of new diabetes. This study has been criticized for use of a β blocker as the comparator and the low doses of the diuretic as a second‐stage drug in the β‐blocker/diuretic group.

As summarized in II, III, when comparing RAS‐blocking regimens with non‐RAS‐blocking regimens on CV end points or surrogate measures, it is evident that combining an RAS blocker plus another agent such as a diuretic results in a consistent end point advantage and surrogate measures benefit. These data substantiate the idea that RAS blockade provides an incremental advantage for end‐organ protection in conjunction with BP reduction.

Table II.

Effects of Renin‐Angiotensin System (RAS)‐Blocking Regimens vs. Non‐RAS‐Blocking Regimens on CV End Points

| HOPE 12 | ALLHAT 14 | LIFE 5 | VALUE 15 | ASCOT 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 9297 | 33,357 | 9193 | 15,245 | 19,342 |

| Age (yr) | 66 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 63 |

| CAD (%) | 80 | 25 | 16 | 45 | 17 |

| Diabetes (%) | 39 | 36 | 13 | 33 | 22 |

| BP advantage (regimen) | RAS | Non‐RAS | RAS | Non‐RAS | RAS |

| SBP difference (mm Hg) | ABPM, −10; office, −3 | −2 to −3 | −1.3 | −2 to −4 | −2.9 |

| CV end points difference (%) | −22 | ND | −13 | ND | −24 |

| Trial acronyms are expanded in text. CV=cardiovascular; CAD=coronary artery disease; BP=blood pressure; SBP=systolic BP; ABPM=ambulatory BP monitoring; ND=no difference | |||||

Table III.

Effects of Renin‐Angiotensin System (RAS)‐Blocking Regimens vs. Non‐RAS‐Blocking Regimens on Surrogate Measures of Cardiovascular Outcome

| Regression/Reduction in: | HOPE 12 (N=9297) | ALLHAT 14 (N=33,357) | LIFE 5 (N=9193) | VALUE 15 (N=15,245) | ASCOT 16 (N=19,342) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left ventricular hypertrophy | NR | NR | Yes | NR | NR |

| Microalbuminuria | Yes | NR | Yes | NR | NR |

| New diabetes mellitus (%) | −32 | −43 | −25 | −23 | −32 |

| Congestive heart failure | Yes | Yes* | No | Yes | NR |

| Trial acronyms are expanded in text. NR=not reported; *diuretic group also reduced congestive heart failure | |||||

One could argue that β blockers also block the RAS and should be listed accordingly. Beta blockers were used in approximately 50% of the patients in HOPE, ALLHAT, and VALUE in the various arms of these studies. In view of that, differentiation is not possible. In LIFE, a losartan regimen was compared with an atenolol regimen and was superior in reducing a composite CV end point despite minimal BP differences. Most of these studies utilized atenolol as the β blocker. These data suggest that there may be a problem with atenolol; possibly, ARBs or ACE inhibitors are better RAS‐blocking drugs than β blockers like atenolol. In ASCOT, there were significant BP differences in favor of the RAS‐blocking regimen with the ACE inhibitor compared with the β‐blocking regimen, which may have obscured possible differences in outcomes between these RAS‐blocking regimens.

RENAL MEASURES OF OUTCOME

The advantage of RAS‐blocking regimens in preventing the doubling of serum creatinine, end stage renal disease, or death has been demonstrated with nondiabetic or diabetic kidney disease.

Jafar et al., 17 in an individual patient meta‐analysis of 11 different clinical trials involving 1860 patients with nondiabetic kidney disease, demonstrated that an ACE inhibitor as part of a BP‐lowering regimen consistently provided an incremental benefit in preventing doubling of serum creatinine or reaching end‐stage renal disease, compared with a non‐ACE inhibitor regimen. This was true for every level of BP achieved throughout the course of the study. The benefit of ACE inhibition was particularly prominent in patients with proteinuria. These results clearly illustrate the advantage of blocking the RAS.

The Collaborative Study Group 18 published clinical trial evidence in 1993 in patients with diabetic kidney disease demonstrating that in type 1 diabetics, incorporating the ACE inhibitor captopril into the BP‐lowering regimen provided a statistically significant advantage in reducing the risk of doubling of serum creatinine, dialysis, transplantation, or death. Similar information was provided by the Irbesartan Diabetic Nephropathy Trial (IDNT) 19 and the Reduction of Endpoints in NIDDM with Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan (RENAAL) trial 20 in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. Both of these studies demonstrated a delay in doubling of serum creatinine, end‐stage renal disease, or death with an ARB‐based regimen (losartan in RENAAL, and irbesartan in IDNT) compared with either a traditional (non‐ACE inhibitor) regimen with a diuretic, β blocker, vasodilator, and so on, or a CCB‐based regimen. In these studies, the BP reduction during follow‐up was nearly identical between the ARB regimens and the non‐ARB regimens, demonstrating the incremental advantage of blocking the RAS. Interestingly, these studies also demonstrated that reduction of proteinuria during the course of follow‐up with the RAS‐blocking regimens predicted success in reducing both CV and renal end points. Thus, in patients with diabetic or nondiabetic kidney disease, the combination of lower BP and blocking the RAS provides unequivocal end‐organ protection.

PERSPECTIVE

As presented herein, the dual actions of lowering BP and blocking the RAS with an ACE inhibitor or an ARB (usually in combination with other agents) confers an advantage with regard to end‐organ protection. Not all trials provide the same evidence, but for the most part this is due to different achieved BP during follow‐up. In addition, there may be other confounding variables that are unique to the demographics of the patients or the clinical trial design. The key perspective is that lower BP is always important, but there may be incremental value to blocking the RAS.

Future trials such as the Avoiding Cardiovascular Events Through Combination Therapy in Patients Living With Systolic Hypertension (ACCOMPLISH) study 21 will evaluate whether a diuretic‐based RAS‐blocking regimen or a CCB‐based RAS‐blocking regimen provides greater CV event reduction. 21 In addition, in the future, more effort may be placed on prospective evaluation of surrogate measures as a means of predicting success with therapeutic regimens. For example, will the prevention or delay of new‐onset diabetes prove to be an important measure of therapeutic benefit? Will regression of LVH, prevention of new heart failure, or reduction of albuminuria prove to be a means by which we can access the therapeutic success of BP‐lowering regimens?

In summary, most patients need more than one medication. The dual actions of lowering BP and blocking the RAS with either an ACE inhibitor or an ARB provide an opportunity to provide end‐organ protection and reduce CV events.

Acknowledgments: I wish to acknowledge the expert secretarial assistance of Maureen Sullivan and the editorial help of Marvin Moser, MD. This paper summarizes a discussion that was part of a debate at the American Society of Hypertension Annual Meeting in San Francisco, CA, on May 17, 2005.

References

- 1. Franklin SS, Larson MG, Khan SA, et al. Does the relation of blood pressure to coronary heart disease risk change with aging? The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2001;103: 1245–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289: 2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weir MR, Dzau VJ. The renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system: a specific target for hypertension management. Am J Hypertens. 1999;12: 205S–213S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weir MR, Henrich WL. Theoretical basis and clinical evidence for differential effects of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor subtype 1 blockers. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2000;9: 403–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dahlof B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention for End Point Reduction in Hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet. 2002;359: 995–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Zeeuw D, Remuzzi G, Parving HH, et al. Albuminuria, a therapeutic target for cardiovascular protection in type 2 diabetic patients with nephropathy. Circulation. 2004;110: 921–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ibsen H, Olsen MH, Wachtell K, et al. Reduction in albuminuria translates to reduction in cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients: Losartan Intervention for End Point Reduction in Hypertension Study. Hypertension. 2005;45: 198–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jafar TH, Stark PC, Schmid CH, et al. Proteinuria as a modifiable risk factor for the progression of non‐diabetic renal disease. Kidney Int. 2001;60: 1131–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Verdecchia P, Reboldi G, Angeli F, et al. Adverse prognostic significance of new diabetes in treated hypertensive subjects. Hypertension. 2004;43: 963–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, et al. Age‐specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta‐analysis of individual data for one million adults in. prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360: 1903–1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Turnbull F. Effects of different blood‐pressure‐lowering regimens on major cardiovascular events: results of prospectively‐designed overviews of randomised trials. Lancet. 2003;362: 1527–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, et al. Effects of an angiotensin‐converting‐enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high‐risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000;342: 145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Svensson P, de Faire U, Sleight P, et al. Comparative effects of ramipril on ambulatory and office blood pressures: a HOPE substudy. Hypertension. 2001;38: E28–E32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group . Major outcomes in highrisk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensinconverting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288: 2981–2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, Weber M, et al. Outcomes in hypertensive patients at high cardiovascular risk treated with regimens based on valsartan or amlodipine: the VALUE randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363: 2022–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dahlof B, Sever PS, Poulter NR, et al. Prevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol adding bendroflumethiazide as required, in the Anglo‐Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial‐Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT‐BPLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366: 895–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jafar TH, Stark PC, Schmid CH, et al. Progression of chronic kidney disease: the role of blood pressure control, proteinuria, and angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibition: a patient‐level meta‐analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139: 244–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Bain RP, et al. The effect of angiotensin‐converting‐enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy. The Collaborative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;329: 1456–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, et al. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin‐receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345: 851–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, et al. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345: 861–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jamerson KA, Bakris GL, Wun CC, et al. Rationale and design of the Avoiding Cardiovascular Events Through Combination Therapy in Patients Living with Systolic Hypertension (ACCOMPLISH) trial: the first randomized controlled trial to compare the clinical outcome effects of first‐line combination therapies in hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17: 793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]