Abstract

There is overwhelming evidence that pharmacologic treatment of isolated systolic hypertension (ISH) (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg) reduces cardiovascular events and extends longevity in the elderly; in the very old (80 years or older), the evidence supports decreased incident stroke and heart failure, but is less convincing in terms of longevity. Thus, the inherent increased risk for ISH vascular events highlights the importance of its control. Importantly, ISH in the elderly, primarily related to large artery stiffness, remains more difficult to control than diastolic hypertension in the young, which is primarily related to increased peripheral vascular resistance. Appropriate lifestyle and pharmacologic intervention is indicated in individuals with systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg in general and ≥130 mm Hg in persons with diabetes or chronic kidney disease. Lifestyle intervention may reduce the need for extensive antihypertensive therapy and minimize associated cardiovascular risk factors. To date, only a small percentage of older ISH patients are being treated to goal. Reaching target systolic blood pressure levels most often requires the use of polypharmacy that includes a diuretic and perhaps specific agents that target arterial stiffness and early wave reflection.

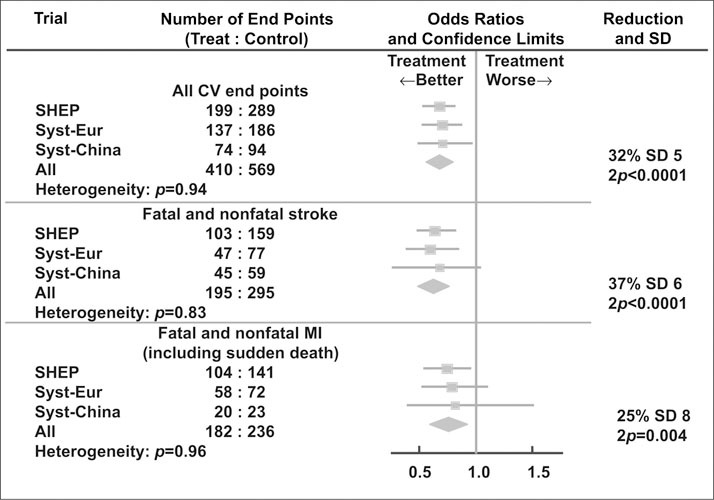

During the past few decades, the therapeutic approach in older hypertensive patients has changed markedly. In the early 1970s, prevailing wisdom questioned the benefit of antihypertensive agents in patients older than 65 years. Beginning in the early 1990s, the publication of three major placebo‐controlled studies that specifically addressed the treatment of isolated systolic hypertension (ISH) in older patients changed the perception of the significance of systolic blood pressure (SBP) control. In 1991, the landmark Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) study first established that older patients with ISH benefited from treatment. The Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst‐Eur) and the China (Syst‐China) trials corroborated these findings. In a meta‐analysis of the 11,825 patients aged 60 years or older who participated in these three major trials (Figure), antihypertensive treatment significantly reduced fatal and nonfatal coronary events by 25%, fatal and nonfatal strokes by 37%, all cardiovascular events by 32%, cardiovascular mortality by 25%, and total mortality by 17%. Additionally, a highly significant 49% reduction in fatal and nonfatal heart failure was reported from the SHEP study. Evidence of treatment benefit from this meta‐analysis was strong for older patients with SBP ≥160 mm Hg (stage 2 ISH); treatment benefit is weaker for SBP 140–159 mm Hg (stage 1 ISH) in the absence of other risk factors, target organ damage, or prior cardiovascular events. These studies negate prior assumptions that age‐related changes in blood pressure (BP) are benign and reinforce the emerging paradigm that treatment will benefit patients with elevated SBP, even when they have normal or low diastolic BP (DBP). Furthermore, the benefit‐to‐risk ratio of antihypertensive therapy is higher in the elderly than in younger or middle‐aged patients.

Figure.

Effect of antihypertensive drug treatment on fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular (CV) end points in three outcome trials in older patients with isolated systolic hypertension. SHEP=Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program; Syst‐Eur=Systolic Hypertension Europe; Syst‐China=Systolic Hypertension China; MI=myocardial infarction. Reproduced with permission from Staessen JA, Wang JG, Thijs L, et al. J Hum Hypertens. 1999;13:859–863.

What evidence do we have that treating ISH in the very old is beneficial? A meta‐analysis of six major trials that included 1670 patients aged 80 years or older suggested that even the very old may benefit from antihypertensive treatment. In these patients, active treatment produced a 34% reduction in stroke (p=0.014), a 39% reduction in heart failure (p=0.01), and a 22% reduction in major cardiovascular events (p=0.01). The reduction in coronary events was not statistically significant, and a nonsignificant 6% increase in mortality was observed. Indeed, there is disagreement as to whether nonsustained systolic hypertension is innocuous compared with true normotension in the elderly patient. The Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET), a more definitive intervention trial of the very old (age 80 or older) utilizing a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled protocol in 2100 subjects with ISH, is in progress. Until the results of this study are known, it would be inappropriate to withhold antihypertensive treatment in this age group. Even though we may not extend the lives of octogenarians, effective treatment of ISH may enhance the quality of their remaining years through prevention of strokes, heart failure, and major cardiovascular complications.

THERAPEUTIC TARGET GOALS FOR ISH

There are specific directives for treatment of hypertension, such as the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) and World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for the optimal reduction of BP to achieve maximum benefit from antihypertensive therapy. These guidelines, based on observational studies as well as on outcome trials, suggest that low‐risk patients with ISH be treated to a target goal of SBP <140 mm Hg. For high‐risk subjects with diabetes, renal impairment, or heart failure, the therapeutic target goal is SBP <130 mm Hg and DBP <80 mm Hg.

LIFESTYLE INTERVENTION IN ISH

A variety of lifestyle interventions have been shown to lower BP, with the most effective being successful weight reduction in obese hypertensives. Reducing weight is of special importance if the elderly hypertensive has diabetes. Even a reduction of 10–15 lb can have a significant effect in lowering BP. Unfortunately, most patients are refractory to successful weight reduction and, even when partially successful, tend to have a high percentage of recidivism by 6–12 months. The older hypertensive patients are usually more salt‐sensitive than the young, but successful salt restriction is difficult because almost 80% of dietary salt is contained in commercially processed foods. The more recent use of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, rich in fruits, vegetables, and high‐calcium but low‐animal‐fat foods, has been successful in reducing BP in older hypertensives even when consuming average salt intakes. Heavy alcohol intake can precipitate or worsen hypertension in older patients and is frequently refractory to usual drug therapy.

Except for the unusual patient, lifestyle intervention is generally unsuccessful in fully correcting ISH. In addition to partial reduction in BP, however, lifestyle intervention may reduce the need for extensive antihypertensive therapy and minimize associated cardiovascular risk factors. Finally, the greatest chance of success with lifestyle intervention is primary prevention, i.e., preventing high‐normal BP from progressing to stage 1 ISH or systolic‐diastolic hypertension.

ANTIHYPERTENSIVE DRUG THERAPY FOR OLDER PERSONS

The Blood Pressure Treatment Trialists' Collaboration, a meta‐analysis of 29 trials involving 162,341 persons with a mean age of 65 years, concluded that all classes of commonly used antihypertensive agents were equally successful in reducing the risk of coronary heart disease and stroke events. Moreover, the reduction in risk was directly proportional to the reduction in SBP. An updated Trialists' Collaboration study, involving 27 randomized trials that included 33,395 individuals with diabetes, also concluded that all BP‐lowering regimens studied were comparable for patients with and without diabetes. These conclusions were supported by the Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT), an outcome trial of 33,357 high‐risk subjects with a mean age of 67 years. ALLHAT showed that a thiazide‐type diuretic (chlorthalidone) was equally effective in reducing the primary end points of nonfatal myocardial infarction and coronary heart disease deaths when compared with the calcium channel blocker (CCB) amlodipine or the angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) lisinopril.

Optimal treatment of ISH should not only reduce peripheral resistance, but also reduce large artery stiffness and the early wave reflection generated by that stiffness. Most conventional antihypertensive drugs, however, fall short of optimally reducing age‐related increases in pulse pressure. Therapeutic benefit may result from at least five different mechanisms (Table I). First, reduction of peripheral resistance downstream will decrease large artery stiffness upstream by a reduction in distending pressure that decreases the stretch on elastic arteries; a variety of antihypertensive agents that dilate arterials work in this manner. Second, long‐term reduction in cardiac afterload will eventually result in regression of left ventricular hypertrophy, regression of vascular smooth muscle hypertrophy, and remodeling of small blood vessels toward a normal wall‐to‐lumen ratio. Indeed, the ability of ACEIs and angiotensin receptor blockers to promote regression of left ventricular hypertrophy and arterial remodeling may have important long‐term benefits in reducing arterial stiffness. Third, vasodilatation of small arteries will shorten the artery reflection sites, decrease early wave reflection, decrease aortic late SBP peaking, and hence decrease cardiac afterload without a structural change in arterial stiffness. Nitrates, in doses that do not affect peripheral vascular resistance, have been shown to decrease early wave reflection, decrease central pulse pressure, and hence lower left ventricular afterload—all without a significant change in arterial stiffness. Fourth, therapy that blocks excessive aldosterone at the tissue level may, over time, result in regression of fibrosis in the heart, renal mesangium, and large blood vessels. Indeed, spironolactone and eplerenone may prove to be of value in reversing the stiffness of arteries in persons with ISH. Fifth, miscellaneous approaches may decrease arterial stiffness by poorly understood mechanisms. Diuretics that achieve negative salt balance, and low‐salt diets, can reduce arterial stiffness. Other possible destiffening strategies include aerobic exercise, 3‐hydroxy‐methyglutaryl‐coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins), and effective control of blood glucose in diabetic patients.

Table I.

Therapeutic Approaches to Decrease Arterial Stiffness

| General reduction in arterial stiffness |

| Reduction of peripheral vascular resistance (most agents) |

| Regression of left ventricular hypertrophy and arterial remodeling (angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers) |

| General reduction in early wave reflection |

| Vasodilation of small arteries (nitrates) |

| Specific reduction in arterial stiffness |

| Reduce cardiac and renal fibrosis (aldosterone inhibitors) |

| Miscellaneous mechanisms to reduce arterial stiffness |

| Diuretics and reduced dietary NaCl intake |

| Aerobic exercise, lipid control, glucose control |

The optimal strategy in treating ISH is to maximize SBP reduction while minimizing the reduction in DBP: the higher the pulse pressure (in part, age‐related), the greater will be the fall in SBP as compared with the fall in DBP with conventional antihypertensive agents. Therefore, antihypertensive therapy will maximize the decrease in pulse pressure and minimize the further reduction in DBP, in direct proportion to the age of the patient and the extent of large artery stiffness.

The question of which drug class is best suited to start first in patients with ISH may be a moot point. Although diuretics and CCBs have been shown to be most effective in decreasing BP and reducing cardiovascular events in the major geriatric hypertension intervention trials of ISH, it should be remembered that reaching goal therapy is generally more difficult in geriatric ISH than in younger persons with systolic‐diastolic hypertension. In practice, a combination of two or more drug classes will be necessary for BP control in the majority of patients with ISH. The use of combination therapy generally increases BP reduction at lower doses of the component agents and often reduces adverse events when compared with higher‐dose monotherapy. Elevations in SBP by ≥20 mm Hg and DBP by ≥10 mm Hg above goal (the “20/10” rule) will often require combination therapy from the start in order to achieve goal therapy within a relatively short time and thereby minimize cardiovascular events. Low‐dose diuretics should almost always be part of combination therapy because of their efficacy in BP reduction, minimal adverse events, and low cost.

There is always potential for adverse events in reducing BP in the elderly, but the available evidence would suggest that these are no more frequent in the elderly than in younger hypertensive subjects. It may be appropriate, however, to start with lower doses of medication in the elderly, especially in the presence of some element of postural orthostasis, and then titrate against response and symptoms. Finally, BP should be monitored in the upright as well as sitting positions to prevent overtreatment and the development of orthostatic hypotension.

UNSATISFACTORY CONTROL RATES FOR ISH

The Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC VI) and the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) have reported on the poor levels of awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States. Indeed, only one in five elderly patients with uncomplicated hypertension and one in 10 patients with hypertension complicated by diabetes or renal disease are being treated to goal therapy. In general, the older the person, the more difficult it becomes to reach SBP goal. Many factors may contribute to the inadequate treatment of hypertension (Table II). Of primary importance is the accurate measurement of BP in the office/clinic and in the home environment. Both physician bias toward focusing primarily on DBP rather than on SBP goal, and physician fear of excessive lowering of DBP, have contributed to poor SBP control. This fear of excessive therapeutic lowering of DBP—the so‐called J‐curve phenomenon—has been exaggerated. If there is any significant risk of precipitating an ischemic cardiac event with therapy‐induced low BP, it would occur only with DBP reduction to <60 mm Hg, as indicated in a post hoc analysis of the SHEP study. Other reasons why ISH patients are poorly controlled include: 1) failure to use proper doses of medication; 2) failure to use polypharmacy; 3) failure to use a diuretic as part of polypharmacy; 4) failure to use effective drug combinations; 5) failure to titrate doses upward; and 6) failure to detect patient poor compliance or noncompliance with therapy.

Table II.

Barriers to Optimal Control of Hypertension

| Inaccurate measurement of blood pressure (BP) |

| Focusing on diastolic BP rather than systolic BP goal |

| Failure to consider absolute global risk |

| Failure to advocate lifestyle modifications |

| Failure to use polypharmacy |

| Failure to use a diuretic as part of polypharmacy |

| Failure to use effective drug combinations |

| Failure to titrate doses upward |

| Fear of reaching excessively low diastolic BP |

| The patient with truly resistant hypertension |

| Behavioral barriers |

Suggested Reading

- •. Nichols WW, O'Rourke ME McDonald's Blood Flow in Arteries. 5th ed. London, England: Hodder Arnold; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- •. Safar ME, Levy BI, Struijker‐Boudier H. Current perspectives on arterial stiffness and pulse pressure in hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. Circulation. 2003;107:2864–2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •. Kass DA. Ventricular arterial stiffening. Hypertension. 2005;46:185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •. Franklin SS, Jacobs MJ, Wong ND, et al. Predominance of isolated systolic hypertension among middle‐aged and elderly US Hypertensives—analysis based on NHANES III. Hypertension. 2001;37:869–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •. Franklin SS, Gustin W 4th, Wong ND, et al. Hemodynamic patterns of age‐related changes in blood pressure. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1997;96:308–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •. Franklin SS, Khan SA, Wong ND, et al. Is pulse pressure useful in predicting risk for coronary heart disease? The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1999;100:354–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •. Franklin SS, Pio JR, Wong ND, et al. Predictors of new‐onset diastolic and systolic hypertension. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2005;111:1121–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •. Staessen JA, Fagard R, Thijs L, et al. Subgroup and per‐protocol analysis of randomized European Trial on Isolated Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1681–1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •. Gueyffier F, Bulpitt C, Boissel JP, et al. Antihypertensive drugs in very old people: a subgroup meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Lancet. 1999;353:793–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •. Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists' Collaboration . Effects of different blood‐pressure‐lowering regimens on major cardiovascular events: results of prospectively‐designed overviews of randomized trials. Lancet. 2003;362:1527–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •. The ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group . Major outcomes in high‐risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blockers vs diuretic. The Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288:2981–2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]