Abstract

In the past 2 decades, calcium channel blockers have emerged as important and useful agents for treating hypertension. The safety of this drug class has been vigorously debated for some time, and it has only been in the past few years that such debate has been quieted by favorable outcomes data with these compounds. Calcium channel blockers are a heterogeneous group of compounds as alike as they are dissimilar. Calcium channel blockers can be separated into dihydropyridine and nondihydropyridine subclasses, with representatives of the latter being verapamil and diltiazem. A lengthy treatment experience exists for verapamil, a compound that has progressed from an immediate‐release to a sustained‐release and, more recently, a delayed/sustained‐release formulation designated for administration at bedtime. This latter formulation synchronizes drug delivery with the early morning rise in blood pressure, which is a particularly attractive feature when viewed in the context of the distinctive pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic features of verapamil.

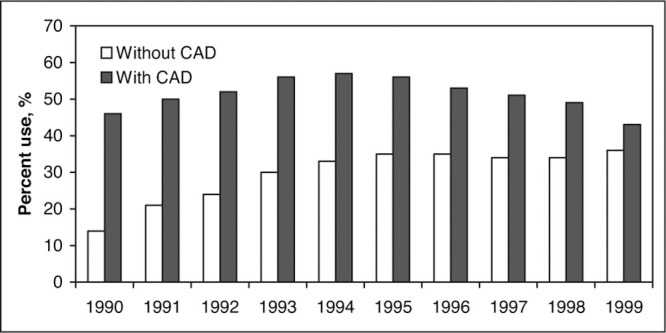

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) are accepted antihypertensive drugs among health care providers. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 The Cardiovascular Health Study 4 surveyed 5775 participants 65 years or older and found that overall CCB use had increased from 14% to 36% during a 10‐year period from 1990 to 1999 notwithstanding a decline (from a peak of 57% in 1994 to 43% in 1999) in their use among patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) (Figure 1). 4

Figure 1.

Percentage use of calcium antagonist therapy from 1990 to 1999 in the Cardiovascular Health Study (N=5775). CAD indicates coronary artery disease (myocardial infarction, angina, or coronary revascularization). Data reproduced with permission from Psaty et al. 4

This steady rise in the use of CCBs was somewhat surprising for 2 reasons: first, there were scant outcomes data to support such widespread use; and second, there existed some academic controversy regarding CCB use being accompanied by an excess of cardiovascular events, an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, and development of cancer. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 These factors, which arguably should have negatively impacted prescriptions for CCBs, were effectively offset by aggressive marketing fueled by the observation that CCBs were capable of significantly reducing blood pressure (BP) in most hypertensive patients. 12 , 13

BASIC PHARMACOLOGY OF CCBs

CCBs are a heterogeneous group of compounds with distinctive structures and pharmacologic actions. There are 3 subclasses of CCBs; this explains many of the differences observed with these agents. These subclasses are the phenylalkylamines (eg, verapamil), the benzothiazepines (eg, diltiazem), and the dihydropyridines (eg, nifedipine, amlodipine, isradipine). The within‐group differences among the CCBs, however, are abundant—with various class members having distinguishing structures and differing pharmacologic actions. All available CCBs are vasodilators, and therein lies their ability to reduce BP. The relative potency of an individual CCB as a vasodilator varies, with dihydropyridine‐type compounds such as nifedipine regarded as the most potent subclass, and verapamil and diltiazem being comparably less potent. 14

In vitro, several calcium antagonists (eg, nifedipine, nisoldipine, isradipine) bind with some selectivity to the L‐type calcium channel present in blood vessels, whereas verapamil binds equally well to cardiac and vascular L‐type calcium channels. 15 , 16 The applicability of these in vitro findings to treatment response in humans remains ill‐defined. In vitro, all CCB subclasses both depress sinus node activity and slow atrioventricular (AV) conduction. Only verapamil and diltiazem delay AV conduction or cause sinus node depression at doses in common use clinically. 14 In this regard, diltiazem (and less so verapamil) are used intravenously (IV) and orally for acute and chronic rate control, respectively, in patients with atrial fibrillation and normal left ventricular function. 17 , 18

Similarly, all CCB subclasses exhibit a concentration dependent negative inotropic effect in vitro, but only verapamil and diltiazem do so in vivo. The disparities between the in vitro and in vivo effects may relate, in part, to the sympathetic activation triggered by dihydropyridine‐induced vasodilation, which blunts any direct negative chronotropic and inotropic effects; there is active debate as to the degree to which dihydropyridine CCBs activate the sympathetic nervous system. 19

PHARMACODYNAMICS OF CCBs

In addition to the smooth muscle relaxation that occurs with CCBs, there are additional effects with these compounds that can potentially modify BP, including: (1) a natriuretic ability, 20 (2) inhibition of both aldosterone release and growth and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle and fibroblasts, 21 , 22 and (3) interference with α2‐ and angiotensin‐mediated vasoconstriction. 23 Also, CCBs have well‐documented antiatherogenic effects in animal models. These latter findings have not been duplicated in human studies. 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 Finally, dihydropyridine CCBs increase or fail to reduce intraglomerular pressure, abolish renal autoregulatory ability, and increase proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis trends.

Verapamil exhibits the aforementioned pharmacodynamic actions unique to CCBs with some exceptions: first, unlike dihydropyridine CCBs, verapamil does not increase proteinuria and/or glomerulosclerosis in experimental models of renal failure. 28 Similarly, this compound is antiproteinuric in humans whether given alone or in conjunction with an angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor. 29 Second, the interference with α2‐mediated vasoconstriction may be less with verapamil than is the case for a dihydropyridine CCB such as nicardipine. 30 Finally, verapamil has been found to be more effective than the diuretic chlorthalidone in promoting regression of thicker carotid lesions, although cardiovascular outcomes did not differ. 27

PHARMACOKINETICS OF CCBs

There are differences in the time‐to‐peak concentration and the elimination half‐life among the various CCBs (Table I). All except amlodipine, lacidipine, and lercanidipine are short‐acting unless novel drug delivery systems are used to prolong their delivery time and duration of action. 31 The short plasma half‐life of lercanidipine is somewhat misleading given its long duration of action. 32 The explanation for this pharmacologic discrepancy lies in the fact that lercanidipine rapidly affixes to the effect compartment, which is the vascular wall. Nimodipine is a CCB approved for short‐term use in patients who have sustained a recent subarachnoid hemorrhage. Diltiazem, nicardipine, and verapamil are the only CCBs presently available in IV formulations. Several CCBs (Covera‐HS [Pfizer Inc, New York, NY], Verelan PM [Elan Corporation, plc, Gainesville, GA], and Cardizem LA [Biovail Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Bridgewater, NJ]) have been designed as chronotherapeutic formulations. 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 Cardiovascular events are more apt to occur in the early morning hours; thus chronotherapeutic delivery systems were created to synchronize drug delivery with the time of peak cardiovascular events. 34 , 35

Table I.

Comparative Pharmacokinetics of Calcium Channel Blockers

| Drug | Absorption, % | Bioavailability, % | Protein Binding, % | Time to Peak, h | Elimination Half‐life, h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amlodipine | >90 | 60–65 | 95 | 6–12 | 35–45 |

| Diltiazem CD | 95 | 40 | 70–80 | 10–14 | 5–8 |

| Felodipine ER | >99 | 20 | 99 | 2.5–5 | 10–17 |

| Isradipine CR | 90–95 | 15–24 | 95 | 7–18 | 8 |

| Lercanidipine | 44 | 10–12 | 98 | 2–3 | 8–10 |

| Nicardipine SR | >90 | 35 | >90 | 1–4 | 8.6 |

| Nifedipine CC | >90 | 84–89 | 92–98 | 2.5–12 | 7 |

| Nisoldipine CC | >80 | 5 | >99 | 6–12 | 7–12 |

| Verapamil SR | >90 | 20–35 | >90 | 5.2–7.7 | 4.5–12 |

| CD indicates controlled delivery; ER, extended release; CR, controlled release; SR, sustained release; and CC, coat‐core. Adapted with permission from Prisant. 41 | |||||

After oral dosing, all 3 subclasses of CCBs undergo extensive first‐pass metabolism at the level of the enterocyte as well as within the liver. 37 The absolute bioavailability for CCBs ranges from 20% for verapamil to over 90% for amlodipine. 38 All CCBs are metabolized by the 3A4 isozyme of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system. Verapamil and diltiazem are both substrates for and act to suppress CYP3A4 activity, whereas other CCBs do not suppress CYP3A4 activity. CCBs are minimally renally cleared and do not require dose adjustment in renal failure on a pharmacokinetic basis. 39

Verapamil is administered as a racemic mixture. It is almost completely absorbed (90%) from the gastrointestinal tract following oral administration and undergoes extensive first‐pass metabolism. The metabolism of verapamil is stereoisomer‐specific and, in kind, dependent on the route of administration and the rate and extent of release from the dosage form in use. With immediate‐release verapamil, the systemic bioavailability ranges from 33% to 65% for the R‐enantiomer and from 13% to 34% for the S‐enantiomer. 40 The absolute bioavailability of this medication increases with repetitive dosing. During long‐term oral administration, nonlinear drug accumulation also occurs in relationship to a reduction in systemic clearance, and thereby a prolongation of its half‐life. This process lends itself to the possibility of immediate release forms of verapamil being administered twice (rather than 3 times) daily (Table II). 41 , 42

Table II.

Pharmacokinetics of Verapamil

| Absorption, % | >90 |

| Bioavailability, % | 10–20 |

| Protein binding, % | |

| R‐isomer | 94 |

| S‐isomer | 88 |

| Volume of distribution, L/kg | 3.8 |

| Elimination half‐life, h | |

| Acute | 2–6 |

| Chronic | 8–12 |

| Clearance, L/h/kg | 0.51–1 |

| Active metabolite | Norverapamil |

| Therapeutic plasma concentrations, ng/mL | 80–300 |

| Adapted from Weir and Zachariah. 42 | |

N‐dealkylation and O‐demethylation are the primary metabolic pathways for verapamil. There are several metabolites of verapamil. The metabolism of verapamil is heavily dependent on hepatic blood flow, and its clearance decreases with aging. Verapamil is a substrate for cytochrome CYP3A4 and P‐glycoprotein; clearance is decreased in women—presumably because of a lesser amount of CYP3A4 present in women. 43 Clearance is not significantly decreased per se in renal failure.

DRUG DELIVERY SYSTEMS

Drug delivery systems for CCBs are designed to prolong the duration of the drug, to reduce dosing frequency, and to diminish side effects (Table III). Sustained‐release delivery systems do, however, have certain disadvantages, including: (1) a lag phase in achieving the desired pharmacodynamic effect when therapy is started, (2) the potential for sustained toxicity/side effects, (3) decreased drug availability for absorption with rapid gut motility, and (4) adverse reactions directly attributable to the structural nature of the delivery system. One should be mindful of differing time courses of absorption and therefore effect when switching from one delivery system (same drug or different compound) to another.

Table III.

Novel Drug Delivery Systems for Calcium Antagonists

| Generic Name | Brand Name | Dosing Interval | Delivery System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diltiazem | Cardizem SR* | bid | Coated beads (multiple) |

| Cardizem CD* | qd | Coated beads (2 populations) | |

| Cardizem LA* | qd hs | Coated beads (multiple) | |

| Tiazac* | qd | Coated beads (multiple) | |

| Dilacor† | qd | Geomatrix | |

| Felodipine | Plendil‡ | qd | Coat core |

| Isradipine | DynaCirc CR§ | qd | Osmotic pump |

| Nicardipine | Cardene SR|| | bid | Coated beads and powder |

| Nifedipine | Procardia XL¶ | qd | Osmotic pump |

| Adalat CC# | qd | Coat core | |

| Nisoldipine | Sular** | qd | Coat core |

| Verapamil | Calan SR¶ | qd‐bid | Sodium alginate matrix |

| Isoptin SR†† | qd‐bid | Sodium alginate matrix | |

| Verelan‡‡ | qd | Coated beads (multiple) | |

| Covera‐HS¶ | qd hs | Osmotic pump with delay coat | |

| Verelan PM‡‡ | qd hs | Multiple beads with delay coat | |

| SR indicates sustained release; CD, controlled delivery; and CR, controlled release. *Biovail Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Bridgewater, NJ. †Watson Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Corona, CA. ‡AstraZeneca LP, Wilmington, DE. §Reliant Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Liberty Corner, NJ. ||Roche Laboratories Inc, Nutley, NJ. ¶Pfizer Inc, New York, NY. #Bayer Pharmaceuticals Corporation, West Haven, CT. **First Horizon Pharmaceutical Corporation, Alpharetta, GA. ††Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL. ‡‡ Elan Corporation, plc, Gainesville, GA. Adapted with permission from Prisant. 41 | |||

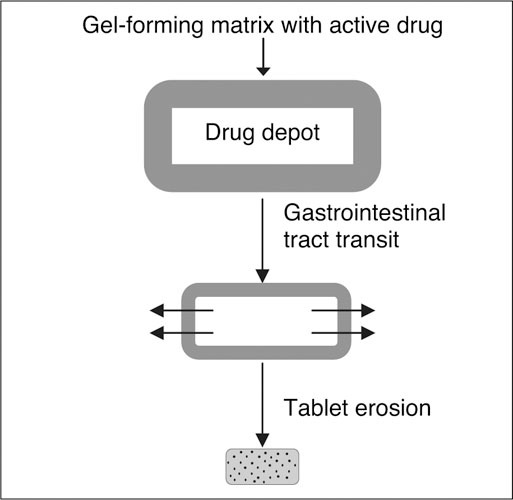

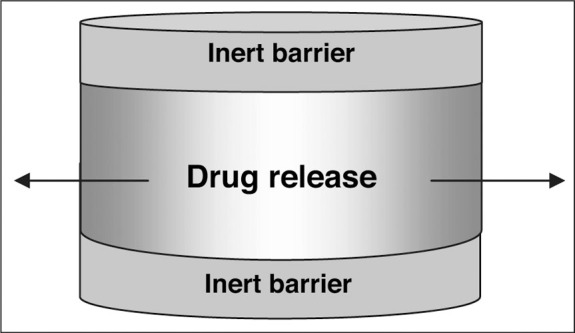

Plendil (AstraZeneca LP, Wilmington, DE), Adalat CC (Bayer Pharmaceuticals Corporation, West Haven, CT), and Sular (First Horizon Pharmaceutical Corporation, Alpharetta, GA) all use the coat‐core system, which is a hydrophilic gel surrounding active drug (Figure 2). 41 The drug diffuses across the hydrophilic gel matrix coat as it passages through the gastrointestinal tract and the matrix/drug depot eventually erodes. Crushing or dividing the tablet changes the delivery characteristics of the system such that it becomes an immediate‐release preparation. As such, there is a greater likelihood of rapid increases in plasma concentrations and associated side effects: flushing, hypotension, and tachycardia. 44

Figure 2.

Coat‐core system. This delivery system is used with nifedipine, nisoldipine, and felodipine. Reproduced with permission from Prisant. 41

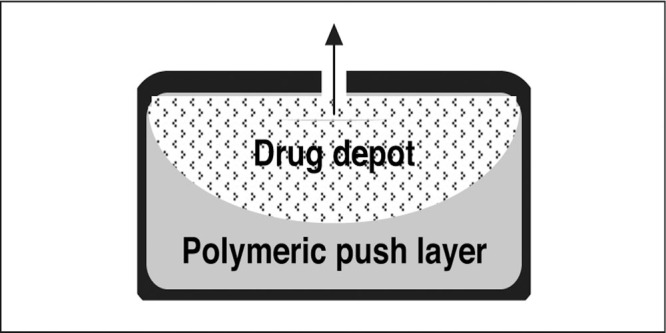

The osmotic pump or gastrointestinal therapeutic system provides a form of zero‐order drug delivery and is used with Procardia XL (Pfizer Inc), DynaCirc CR (Reliant Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Liberty Corner, NJ), and Covera‐HS (Figure 3).41, 45, 46 The osmotic pump contains 2 compartments: a polymeric push compartment and an osmotic drug core; the entire tablet is surrounded by a cellulosic membrane that is water‐ but not drug‐ or excipient‐permeable. 47 There is a laser‐drilled opening on the drug side of the tablet to permit delivery of the drug as the polymeric push compartment expands. The osmotic pump is hard, which increases the possibility of chipping teeth if inadvertently chewed, obstructing the gastrointestinal tract if lodging occurs at the site of a stricture, and/or possibly eroding through diverticula. 48

Figure 3.

Osmotic pump delivery system. This delivery system is used with nifedipine, isradipine, and verapamil. Reproduced with permission from Prisant. 41

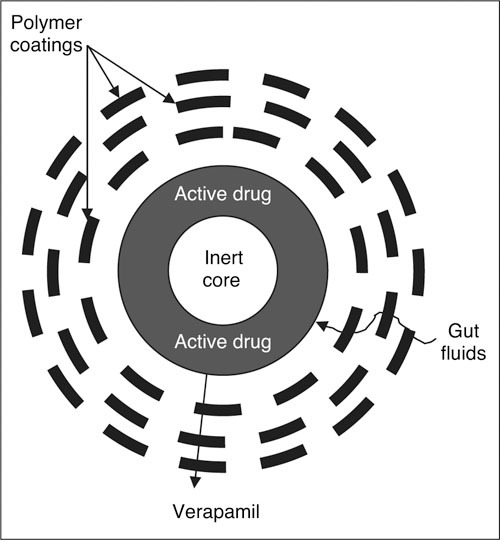

Cardizem SR, Cardizem CD, Cardizem LA, Tiazac (Biovail Pharmaceuticals, Inc), Verelan, Verelan PM, and Cardene SR (Roche Laboratories Inc, Nutley, NJ) all use an encapsulated bead delivery system (Figure 4). 41 , 44 Cardene SR is a mixture of 25% immediate‐release powder and 75% slow‐release beads. Cardizem CD consists of 2 types of beads, each having a different polymer coat thickness (40% with a thin and 60% with a thicker polymer coat). 49 In these preparations, the thickness of the polymer coat determines the time course of drug delivery. Tiazac consists of coated beads with a monolayer microporous semi‐permeable polymer that controls the rate of drug diffusion into the gastrointestinal tract. Cardizem LA differs from Tiazac in the amount of coating applied to the individual beads. If taken at bedtime, Cardizem LA attains peak plasma levels between 6 AM and noon. 44

Figure 4.

Spheroidal oral drug absorption system. Bead delivery systems are used with verapamil, diltiazem, and nicardipine. Reproduced with permission from Prisant. 41

Dilacor XR (Watson Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Corona, CA) uses the completely biodegradable Geomatrix (SkyePharma plc, London, England) tablets, which consist of 2 slow‐hydrating barriers sandwiching a hydrophilic matrix core (Figure 5). 41 , 44 Diltiazem diffuses at a constant rate across the unprotected sides of the active layer as the volume of the dry tablet increases from 0.19 cc to 2.21 cc with complete hydration. Each tablet contains 60 mg of diltiazem; thus 3 tablets are encapsulated to make up the 180‐mg dose. 44

Figure 5.

Geomatrix (SkyePharma plc, London, England) delivery system. This delivery system is used with diltiazem. Reproduced with permission from Prisant. 41

Covera‐HS has 2 laser‐drilled holes that facilitate drug release and a special delay coat to time the release of verapamil in the hours before awakening when it is taken at bedtime. Verelan and Verelan PM use encapsulated beads. 44 Verelan is a multiparticulate bead or spheroidal oral drug absorption system (SODAS, Elan Corporation plc) that consists of 1‐mm inert beads surrounded by rate‐controlling polymers that allow the release of verapamil irrespective of pH (Figure 4). Similar to Verelan, Verelan PM uses water‐soluble and ‐insoluble polymers to delay initial drug release of verapamil for 4 to 5 hours. 50 Isoptin SR (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) and Calan SR (Pfizer Inc) consist of a mixture of verapamil combined with polysaccharide sodium alginate, which absorbs water and assumes a gelatinous quality in the gastrointestinal tract. Diffusion through the matrix and surface erosion of the tablet release the drug. Unlike Verelan, this formulation must be taken with food to avoid what can be substantially higher plasma levels in the fasting state.

NUTRIENT INTERACTIONS

Drug‐drug interactions are commonly recognized in the hypertensive population. Drug‐nutrient interactions are not as well appreciated, but the grapefruit juice‐CCB interaction has been known since 1989. The basis for this interaction has been thoroughly explored and appears to relate to both flavanoid and nonflavanoid components of grapefruit juice‐suppressing enterocyte CYP3A4 activity; presystemic clearance of susceptible (or drugs with a limited absorption) compounds decreases and bioavailability increases. 51

A number of the CCBs are prone to this interaction, with the most prominent interaction occurring with felodipine. Grapefruit juice has the greatest effect on those CCBs with the lowest oral bioavailability. One glass of grapefruit juice more than doubles the bioavailability of standard and extended release felodipine, with considerable interindividual variability. 52 Many studies have shown a greater reduction in BP, a rise in heart rate, and an increase in vasodilatory effects when felodipine is taken together with grapefruit juice. Other dihydropyridines prone to this interaction are nisoldipine and nicardipine. A lesser but still significant interaction has been observed with nimodipine and nitrendipine, which have shown a 50% and 100% increase in bioavailability, respectively, when given with grapefruit juice. Amlodipine and nifedipine are inherently more bioavailable and hence are less affected by grapefruit juice. 51

Although metabolized in vivo by CYP3A4, the nondihydropyridine CCBs diltiazem and verapamil do not have their bioavailability meaningfully altered with the coadministration of grapefruit juice. 53 , 54

DRUG INTERACTIONS

Most CCB drug‐drug interactions are pharmacodynamic in nature, 14 , 55 such as added effects on the AV or sinus nodes (verapamil or diltiazem plus β‐blockers, excess digitalis, or amiodarone), or on systemic vascular resistance (eg, nifedipine plus β‐blockers causing excess hypotension). It is now recognized, however, that verapamil and diltiazem (but probably not nifedipine) inhibit the hepatic oxidation of some drugs, resulting in an increase in blood levels. Such drugs include cyclosporine; the antiepileptic carbamazepine; prazosin; lovastatin, atorvastatin, and simvastatin; theophylline; some human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors; and quinidine. In addition, nifedipine and verapamil increase hepatic blood flow, potentially enhancing first‐pass metabolism of a number of agents, resulting in a decline in steady‐state blood levels. 56

Verapamil and β‐blockers given together carry the risk of added hypotension or nodal inhibition. 55 Verapamil also interacts pharmacokinetically with hepatically metabolized β‐blockers to raise blood levels. 56 Despite such pharmacokinetic interactions (eg, verapamil with propranolol) in normal subjects, pharmacodynamic changes remain a more important consideration for these 2 compounds. 57 The combination of verapamil and β‐blockade improves myocardial function during exercise more so than either agent alone 58 and may also prove additive in the treatment of hypertension. This combination, however, carries a small risk of inhibition of sinus rate, AV conduction, and left ventricular function. 59

Verapamil and other CCBs such as nifedipine, diltiazem, and nicardipine can increase blood digoxin levels by over 50% 60 ; thus, dose reduction of a similar magnitude is warranted. There is an apparent reduction in both the volume of distribution and total body clearance of digoxin that occurs in a dose‐dependent manner with these CCBs. In the setting of digitalis toxicity, rapid IV administration of verapamil is contraindicated because the additive AV nodal inhibitory effects of these 2 agents can prove fatal. Oral verapamil and digitalis can, however, be combined in the absence of digitalis toxicity or AV block, because their pharmacologic sites of action differ; nevertheless, digoxin levels must be carefully monitored. The combination of the 2 medications is one of several options available for the management of supraventricular tachycardias.

The concurrent use of verapamil and the αblocker prazosin results in a significantly greater decrease in BP than when either drug is used alone. The prazosin plasma area under the curve and the peak plasma prazosin level is 50% to 80% higher during concurrent verapamil treatment, 61 which may relate to an increased bioavailability of prazosin in this setting.

Verapamil and quinidine may interact to cause excess hypotension, either by combined inhibition of peripheral α‐receptors or by an increase in quinidine levels owing to a hepatic interaction between these 2 drugs. 62 , 63

SIDE EFFECTS

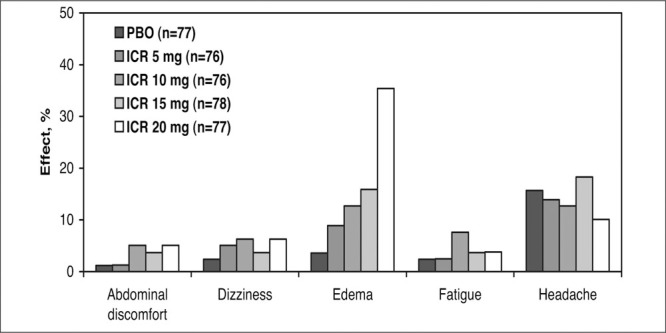

All short‐acting CCBs (and in particular dihydropyridine compounds) cause dose‐dependent flushing, tachycardia, dizziness, and headache due to vasodilatation. Long‐acting or sustained‐release formulations of CCBs are less commonly associated with these side effects; the sustained‐release formulations of CCBs are, however, more likely to be associated with dose‐dependent peripheral edema (Figure 6). 46 CCB‐related peripheral edema is the consequence of greater arteriolar than venular dilation. This mismatch of dilation favors fluid extravasation as capillary pressures rise. 64 , 65 This side effect occurs less commonly with the non‐dihydropyridine CCBs. The peripheral edema associated with CCB use is not associated with weight gain and is not responsive to diuretic therapy.

Figure 6.

Side effects with isradipine controlled‐release (ICR) compared with placebo (PBO). This was a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, multicenter, 9‐week study. The only side effect that was dose‐related was edema. Adapted with permission from Chrysant and Cohen. 46

There appears to be less peripheral edema with the newer dihydropyridine CCBs. In a multicenter, double‐blind, parallel trial of 828 elderly hypertensive patients treated with lacidipine 2 to 4 mg/d, lercanidipine 10 to 20 mg/d, or amlodipine 5 to 10 mg/d, the peripheral edema rates were 4.3%,9.3%, and 19% (P<.0001), respectively. 66

The prevalence of peripheral edema is reduced when an ACE inhibitor is given together with a CCB. In an 8‐week, double‐blind, parallel‐group trial of 563 hypertensive patients, the rate of peripheral edema was 4.9% for amlodipine 5 mg; 23.6% for amlodipine 10 mg; and 2.2% and 1.5%, respectively, for amlodipine 5 mg/benazepril 10 mg, and amlodipine 5 mg/benazepril 20 mg (P<.001). 67 This edema‐attenuating effect of an ACE inhibitor likely relates to the venodilating actions of this drug class and is discussed further below.

Gingival overgrowth occurs with CCBs, cyclosporine, and phenytoin. 68 The prevalence is higher with nifedipine (38%) than diltiazem (21%), verapamil (19%), or controls (4%). 69 Attention to plaque control is important in these patients. Although in most patients this side effect remits with discontinuation of a CCB, on occasion gingivectomy is necessary. 70

CCB use may be accompanied by a worsening of gastroesophageal reflux relating to a reduction in lower esophageal pressures. 71

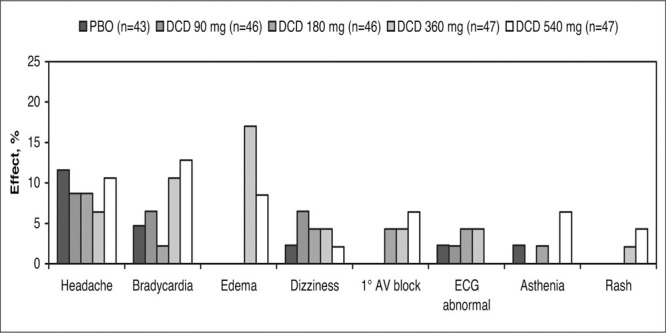

Verapamil and diltiazem are both associated with the general side effects seen with other CCBs, in addition to drug‐specific side effects. Sinus bradycardia and peripheral edema are common with higher doses of diltiazem, and occasionally headache, dizziness, asthenia, fatigue, rash, and first‐degree AV block have been reported (Figure 7). 72

Figure 7.

Side effects of diltiazem controlled‐delivery (DCD). This was a multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo (PBO)‐controlled, parallel‐design trial with a 4‐ to 6‐week PBO baseline and 4‐week treatment period. Sinus bradycardia and edema were treatment‐related adverse events. Derived from data of Felicetta et al. 72

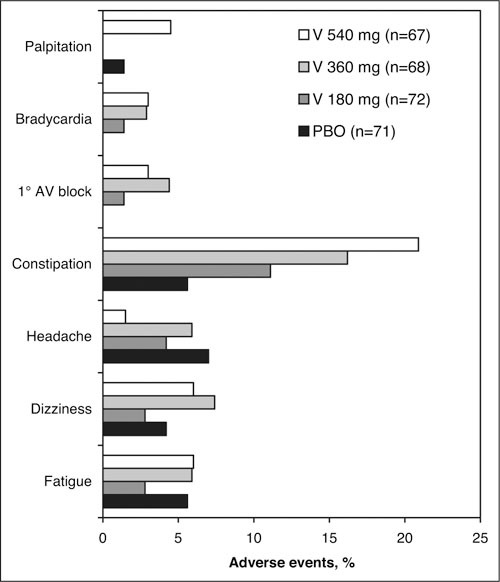

Constipation occurs as a dose‐dependent side effect of verapamil (Figure 8). 73 In that regard, pooled data from 1042 patients on the safety of controlled‐onset, extended‐release verapamil up to 540 mg daily compared with placebo or an active comparator drug found an overall incidence of 13% for constipation, which was slightly higher among patients older than 65. In these studies, placebo constipation rates were surprisingly low—1% to 2%.74

Figure 8.

Side effects with verapamil chronotherapeutic extended‐release (V). This was a double‐blind, placebo (PBO)‐controlled, parallel‐group trial with fixed‐dose treatment for 4 weeks. Constipation is a V–dose‐related adverse event. Derived from data of Cutler et al. 73

Rarely, transaminase values increase with verapamil and complete heart block or skin eruptions can occur with this compound. Both diltiazem and verapamil should be avoided in the presence of systolic heart failure; however, all CCBs should be used cautiously in the heart failure patient (if at all), because use of this drug class can be associated with heart failure exacerbations. 75 , 76

CLINICAL INDICATIONS AND EFFICACY

Table IV lists the CCBs currently marketed in the United States and their labeled indications. Not listed are nimodipine, which is used for subarachnoid hemorrhage, and bepridil, an antianginal drug that is seldom used.

Table IV.

Indications for Calcium Channel Blockers

| Subclass/Generic Name | Brand Name | Stable Angina | Vasospastic Angina | Hypertension | SVT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzothiazepine | |||||

| Diltiazem | Cardizem | X | X | X | |

| Diltiazem | Cardizem SR | X | |||

| Diltiazem | Cardizem CD | X | X | X | |

| Diltiazem | Cardizem LA* | X | X | ||

| Diltiazem | Dilacor XR | X | X | ||

| Diltiazem | Tiazac | X | |||

| Dihydropyridine | |||||

| Amlodipine | Norvasc | X | X | X | |

| Felodipine | Plendil | X | |||

| Isradipine | DynaCirc | X | X | ||

| Isradipine | DynaCirc CR | X | |||

| Nicardipine | Cardene | X | X | ||

| Nicardipine | Cardene SR | X | |||

| Nifedipine | Adalat/Procardia | X | X | ||

| Nifedipine | Adalat CC | X | |||

| Nifedipine | Procardia XL | X | X | X | |

| Nisoldipine | Sular | X | |||

| Phenylalkylamine | |||||

| Verapamil | Calan/Isoptin | X | X | X | X |

| Verapamil | Calan SR | X | |||

| Verapamil | Covera‐HS* | X | X | ||

| Verapamil | Isoptin SR | X | |||

| Verapamil | Verelan | X | |||

| Verapamil | Verelan PM* | X | |||

| SVT indicates supraventricular tachycardia. *Chronotherapeutic delivery system. Brand name owners are identified in Table III. Adapted with permission from Prisant. 41 | |||||

In addition to these labeled indications there are a number of other possible uses for CCBs. In most cases these uses are not supported by definitive clinical trial evidence (Table V).

Table V.

Possible Uses of Calcium Channel Blockers in Vascular Diseases

| Angina pectoris |

| Effort and rest angina |

| Prinzmetal's variant |

| Arrhythmia treatment and prophylaxis (acute and chronic) |

| Verapamil or diltiazem |

| Hypertension |

| Hypertensive emergencies: nicardipine |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: verapamil |

| Primary pulmonary hypertension |

| Peripheral vascular disease |

| Intermittent claudication |

| Raynaud phenomenon |

| Cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage: nimodipine |

| Mesenteric insufficiency |

| Migraine headache prophylaxis |

Antianginal. The antianginal mechanisms of CCBs are complex. These drugs exert vasodilator effects on the coronary and peripheral vessels as well as depressant effects on cardiac contractility, heart rate, and conduction; all of these actions may be important in mediating the antianginal effects of these drugs. 77 These drugs are not only mild dilators of epicardial vessels not in spasm but may markedly attenuate sympathetically mediated coronary vasoconstriction; these actions provide a rational basis for the effectiveness of these drugs in vasospastic forms of angina. In patients with exertional forms of angina, the peripheral vasodilator actions of diltiazem and verapamil and the inhibitory effects on the sinus node attenuate the increases in double product that normally accompany and serve to restrict exercise. 78

The second Danish Infarction Trial (DAVIT‐II) 79 demonstrated the ability of verapamil to reduce reinfarction rate after myocardial infarction. This medication has a well‐documented history as an effective antianginal treatment when directly compared with β‐blockade. 80 The Angina Prognosis Study in Stockholm (APSIS) 81 compared the effects of sustained‐release metoprolol (200 mg) with sustained‐release verapamil (240 mg twice daily) in 809 patients with stable angina pectoris. In this study there was no significant difference between the β‐blocker metoprolol and verapamil in the effect on mortality and/or cardiovascular end points. Withdrawals due to side effects occurred in 11.1% and 14.6% of the metoprolol‐and verapamil‐treated subjects, respectively, suggesting similar tolerability.

Long‐acting CCBs and long‐acting nitrates may be substituted for β‐blockers in angina management if β‐blocker therapy gives rise to unacceptable side effects. β‐Blockers and long‐acting CCBs, unless contraindicated, are also options for use during nitrate‐free intervals in therapy. 82 Several forms of verapamil have indications for the treatment of angina, including immediate‐release Calan, nocturnally administered Covera‐HS, and immediate‐release Isoptin (Table IV). 83 Nocturnally administered verapamil is particularly effective (compared with amlodipine) in decreasing ambulatory myocardial ischemia, especially during the hours of 6 AM to noon. 84

Antiarrhythmics. Among the CCBs, verapamil and diltiazem are preferred therapies in the management of supraventricular arrhythmias, with both drugs being available for IV administration (Table VI). 85 Both of these agents slow cardiac conduction and reduce heart rate. Verapamil has a more prominent effect on the AV node than the sinoatrial node; thus the PR interval and the heart rate should be determined before commencing therapy. Oral verapamil is an alternative to slow ventricular response in either atrial flutter or atrial fibrillation with preserved ventricular function and a maintained BP. This is not used very often. Patients with Wolff‐Parkinson‐White syndrome (preexcitation syndrome) with atrial fibrillation, however, should not receive verapamil. In this syndrome, ante‐grade conduction over the accessory pathway may increase with verapamil, with an ensuing increase in ventricular response rate, occasionally deteriorating into ventricular fibrillation. 83

Table VI.

Effects of Diltiazem and Verapamil in the Treatment of Common Arrhythmias

| Effective |

| Sinus tachycardia |

| Supraventricular tachycardia |

| AV nodal reentrant PSVT |

| Accessory pathway reentrant PSVT |

| SA nodal reentrant PSVT |

| Atrial reentrant PSVT |

| Atrial flutter (ventricular rate decreases but the arrhythmia only occasionally converts) |

| Atrial fibrillation (ventricular rate decreases but the arrhythmia only occasionally converts) |

| Ineffective |

| Nonparoxysmal automatic atrial tachycardia |

| Atrial fibrillation and flutter in WPW syndrome (ventricular rate may not decrease) |

| Ventricular tachyarrhythmias* |

| AV indicates atrioventricular; PSVT, paroxysmal supra‐ventricular tachycardia; SA, sinoatrial; and WPW, Wolff‐Parkinson‐White syndrome. *There is limited experience in this area. Adapted from Frishman and Sica. 85 |

Hypertension. CCBs are effective in the treatment of systemic hypertension and hypertensive emergencies. They can be considered possible initial therapy for treatment in many patients with chronic hypertension 86 , 87 and are as effective (if not more so) as other antihypertensive agents in reducing BP. 13 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 The question of whether CCBs precipitate cardiovascular events has been largely settled by trials such as the Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT), 13 the International Verapamil Slow‐Release/Trandolapril Study (INVEST), 92 and the Controlled Onset Verapamil Investigation of Cardiovascular End Points (CONVINCE) study, 93 in which no such association was found.

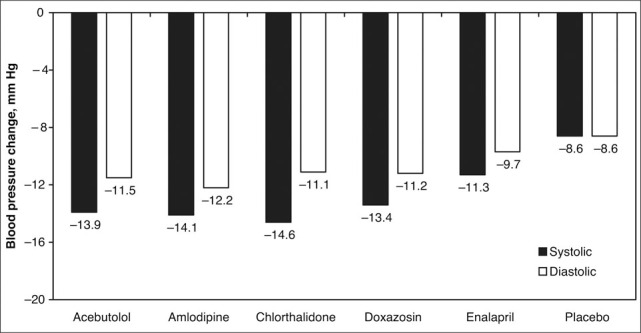

Two studies in particular have directly compared multiple classes of antihypertensive medications with a CCB in terms of efficacy and side effects: the Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study (TOMHS) 90 and the Veterans Administration Cooperative Study. 91 TOMHS was a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial of 902 men and women aged 45 to 69 years with a diastolic BP less than 100 mm Hg randomized to placebo, chlorthalidone 15 mg/d, acebutolol 400 mg/d, doxazosin 2 mg/d, amlodipine 5 mg/d, or enalapril 5 mg/d. As shown in Figure 9, amlodipine was as effective as other antihypertensive agents (and more effective than the ACE inhibitor enalapril) at the dose used. In further findings in TOMHS, the average decrease in low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol was greater with doxazosin than amlodipine (−11.3 mg/dL vs −5.1 mg/dL; P<.01), and the decline in triglycerides was greater with amlodipine than acebutolol (−18.4 mg/dL vs −6.4 mg/dL; P<.01). Amlodipine did not change glucose, potassium, uric acid, or creatinine. The starting dose of amlodipine (81.6%) and acebutolol (77.0%) was more likely to be maintained than placebo (54.6%; P<.01). 90

Figure 9.

Average blood pressure change from baseline at 48 months in the Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study (TOMHS). For systolic or diastolic blood pressure, acebutolol, amlodipine, chlorthalidone, and doxazosin lowered blood pressure more than placebo (P<.01). Data derived from Neaton et al. 90

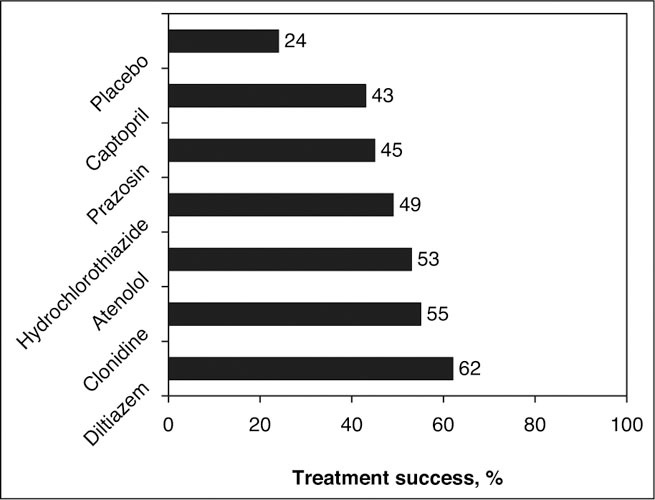

The only other trial that similarly compared multiple classes of antihypertensive drugs with placebo was the Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study, 91 a randomized, double‐blind study. This study included 1292 men with untreated diastolic BP between 95 mm Hg and 109 mm Hg treated in a titrated manner with 1 of 6 drug classes: hydrochlorothiazide (12.5 → 50 mg/d), atenolol (25 → 100 mg/d), clonidine (0.1 → 0.3 mg bid), captopril (12.5 → 50 mg bid), prazosin (2 → 10 mg bid), diltiazem sustained‐release (60 → 180 mg bid), or placebo. Treatment was deemed successful if the diastolic BP dropped below 90 mm Hg after the titration period and remained there at 1 year of treatment (Figure 10). Diltiazem was significantly better than captopril, prazosin, or placebo (P<.05). 91 Among younger and older African Americans, diltiazem achieved the highest treatment success rate after 1 year.

Figure 10.

Comparison of 6 antihypertensive drugs in the Veterans Administration Cooperative Study. Treatment success is determined by a diastolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg after 1 year of treatment. Diltiazem was significantly better than captopril, prazosin, or placebo (P<.05). Adapted with permission from Materson et al. 91

EFFICACY OF CCBs AS MONOTHERAPY

All patient groups with hypertension are to some degree responsive to CCB monotherapy. There are, however, no reliable predictors of the magnitude of the BP reduction to a CCB in particular subsets of patients. Low‐renin, salt‐sensitive, volume‐expanded diabetic and black hypertensive patients are more often responsive to a CCB or a diuretic than to an ACE inhibitor or a β‐blocker. As an example of this, in a double‐blind, positively controlled, forced‐dose titration study comparing atenolol, captopril, and sustained‐release verapamil as single agents in the treatment of 394 black patients with a diastolic blood pressure 95 mm Hg to 114 mm Hg, verapamil was the most effective agent in controlling BP. 94 Of note, there have been occasional reports of differences in CCB metabolism based on ethnicity. One such study showed a slower clearance for nifedipine in black subjects (8.9±0.7 mL/min/kg) compared with white subjects (11.6±0.8 mL/min/kg; P=.00004). 95 The significance of ethnicity‐related difference in CCB metabolism, however, remains unclear.

Age can prove a determinant of the BP response to a CCB as well as to some other antihypertensive agents. Elderly patients are more sensitive to CCBs as a function of age‐related alterations in pharmacokinetics, which may explain, in part, the effectiveness of drugs in this class for the treatment of isolated systolic hypertension. 96 CCBs differ from ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) in that their BP‐lowering effect is not enhanced with dietary Na+ restriction. Although sex has not been viewed as an important factor in the response to antihypertensive agents, oral verapamil is cleared more slowly in women; thus, at comparable doses, plasma concentrations are higher and the effect greater than in men. 97

First‐step CCB therapy becomes a stronger consideration when conditions such as CAD with angina, intermittent claudication, migraine, and/or Raynaud's phenomenon coexist with hypertension. 85 , 98 If a CCB is required in the setting of heart failure marked by a reduced ejection fraction, a dihydropyridine CCB is preferable, although in these situations, an ACE inhibitor, ARB, diuretic, and/or a β‐blocker may be the medication of choice. Diltiazem and verapamil both have negative inotropic effects and can potentially worsen heart failure. 99 Heart rate‐lowering CCBs such as verapamil or diltiazem are preferred if left ventricular hypertrophy, diastolic dysfunction, or supraventricular tachyarrhythmias are present. Dihydropyridine CCBs should not be used as monotherapy in hypertensive patients with chronic kidney disease and proteinuria. 100 Verapamil or diltiazem in combination with other agents are useful therapies in the proteinuric chronic kidney disease patient. 101

EFFICACY OF CCBs WITH OTHER MEDICATIONS

Since most patients demonstrate some response to CCB monotherapy, the question often arises when a CCB is used as initial therapy, how high to titrate the dose before adding a second antihypertensive drug. The response to increasing the dose of a CCB is generally that of additional BP reduction; however, such dose titration occurs with a greater frequency of side effects. CCB‐related side effects often result in drug discontinuation, dosage reduction, and/or addition of a second medication. Split dosing of a CCB does not necessarily ensure a better overall response or less prominent side effects than full‐dose, once‐daily administration of the same compound.

CCBs complement the BP‐lowering effectiveness of all drug classes and work in salt‐sensitive as well as salt‐resistant forms of hypertension. For example, adding a β‐blocker, a peripheral α‐antagonist, an aldosterone receptor antagonist, a thiazide‐type diuretic, and/or an ACE inhibitor (or ARB) to a CCB further reduces BP. Also, the combination of 2 different CCB subclasses may additively reduce BP. 102

β‐Blockers and the dihydropyridine CCBs work by complementary hemodynamic mechanisms, with the CCB lessening any α‐adrenergic reflex vasoconstriction unmasked by β‐blockers and the β‐blocker tempering hemodynamic and neurohumoral changes arising from the dihydropyridine CCB. In a randomized, double‐blind trial, 234 hypertensive patients were randomized to nicardipine 30 mg, propranolol 40 mg, or the combination, each given 3 times daily. 103 The change in average supine BP after 6 weeks was −15.9/−13.8 mm Hg, −15.6/−12.6 mm Hg, and −19.8/−15.7 mm Hg for nicardipine, propranolol, and the combination, respectively. Although the combination was less than additive, there were fewer vasodilatory side effects with the combination therapy (5%) and propranolol mono‐therapy (3%) compared with nicardipine mono‐therapy (14%; p≥05). Combinations of these 2 drug classes generally have not employed nondihydropyridine CCBs out of concern for an excessive effect on sinus and AV nodal function.

Combining an α1‐blocker with a dihydropyridine CCB may prove significantly additive. In a randomized, double‐blind, crossover study, each of 75 patients received amlodipine 10 mg, doxazosin 4 mg, and the combination of amlodipine 5 mg and doxazosin 2 mg daily for 6 weeks after a 2‐ week washout period. 104 The change from baseline was −29/−10 mm Hg for amlodipine monotherapy, −28/−8 mm Hg for doxazosin monotherapy, and −41/−15 mm Hg for the half‐strength combination. One study observed an increase in bioavailability of the α‐blocker terazosin when added to the nondihydropyridine verapamil, suggesting a pharmacokinetic as well as a pharmacodynamic interaction between these 2 drug classes. 105

It had been suggested that thiazide‐type diuretics additively reduce BP with all drug classes other than CCBs. It was originally believed that the natriuretic effect of a CCB effectively substituted for that of a thiazide‐type diuretic; thus, if both drug classes were combined the effects would not be additive. This has not proven to be the case, and factorial design trials have now shown that thiazide‐type diuretics complement the antihypertensive effect of both dihydropyridine and nondihydropyridine CCBs. 106 In the assessment of thiazide‐type diuretic and CCB additivity, a sequence effect may be found. When a CCB is added to a diuretic the antihypertensive effect is clearly greater; conversely, when the order of administration is reversed the potentiating effect is less so. 107

The addition of a dihydropyridine to a nondihydropyridine CCB results in an additive BP‐lowering response. 108 , 109 , 110 Saseen et al 110 reported a decrease in BP when either diltiazem or verapamil was added to nifedipine (all compounds were sustained‐release). Diltiazem, however, more effectively lowered BP than did verapamil in this set of studies—a phenomenon that may have had a pharmacokinetic basis. Of note, mean nifedipine area under the curve values were higher with diltiazem (1430 ng • h/mL) than with verapamil (1134 ng • h/mL; P=.026) (baseline nifedipine levels, 957 ng • h/mL). The combination of verapamil and nifedipine was associated with somewhat increased side effects than was the case for diltiazem and nifedipine. 110

A CCB and ACE‐inhibitor combination (fixed‐dose or otherwise) is more effective at controlling hypertension than either component as mono‐therapy. Several fixed‐dose antihypertensive combinations, which contain an ACE inhibitor and a CCB, are available worldwide. Of the 3 products available in the United States, 2 contain a dihydropyridine CCB (amlodipine/benazepril; felodipine/enalapril) and the other a nondihydropyridine CCB (verapamil/trandolapril). There have been limited head‐to‐head comparisons of these combination medications.

Typically, the CCB component of such fixed‐dose combinations is more long‐acting and dictates the duration of effect. CCBs are intrinsically natriuretic and will induce a state of negative Na+ balance, which can further enhance the antihypertensive effect of an ACE inhibitor. The CCB being combined with an ACE inhibitor may be relevant to the mechanistic basis for additivity. When a dihydropyridine CCB is given together with an ACE inhibitor the latter may attenuate the dose‐dependent sympathetic activation that occurs with a dihydropyridine CCB—a process that does not occur with nondihydropyridine CCBs.

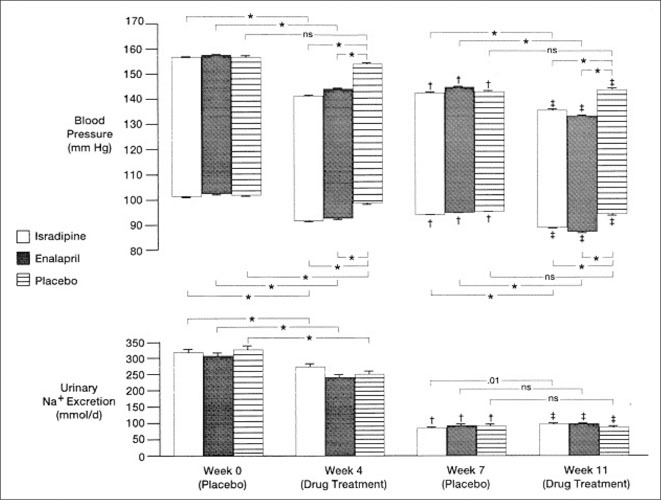

SODIUM INTAKE AND CCB EFFICACY

The BP‐lowering effect of ACE inhibitors (and several other antihypertensive drug classes) is clearly augmented by sodium restriction; this is not the case, however, with CCBs. In a small study, the change in BP before and after verapamil 120 mg 3 times daily on a low‐sodium (9 mEq/d) diet was −18/−11 mm Hg, and on a high‐sodium diet (212 mEq/d) was −19/−14 mm Hg. 111 Another double‐blind study randomized 397 salt‐sensitive hypertensive patients to a dihydropyridine CCB, isradipine (2.5–20 mg twice daily), enalapril (2.5–20 mg twice daily), or placebo to evaluate their response to a low‐ (50–80 mEq sodium/d) and high‐sodium (200–250 mEq sodium/d) diet. 112 This study observed that the decline in BP was greater for isradipine on the high‐ vs low‐sodium diet (14.9±1.5 vs 7.6±1.3 mm Hg for systolic and 10.1±0.6 vs 4.8±0.9 mm Hg for diastolic, respectively [P<.001]) (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Systolic and diastolic blood pressures (Bps) and urinary sodium excretions for patients treated with isradipine, enalapril, and placebo at the beginning (week 0) and end (week 4) of the high‐salt (200–250 mmol Na+/d) and beginning (week 7) and end (week 11) of the low‐salt (50–80 mmol Na+/d) drug treatment phases. Upper end of the bar is systolic and lower end of the bar diastolic BP. SE indicated by horizontal lines. Bracketed symbols or numbers indicate significance between treatment groups. NS indicates not significant.*P≤0001. †P≤0001 vs week 0. ‡P≤0001 vs week 4. There were no significant differences in urinary Na+ excretion between isradipine‐ or enalapril‐treated vs placebo‐treated hypertensive patients at weeks 0, 4, 7, or 11. Reproduced with permission from Chrysant et al. 112

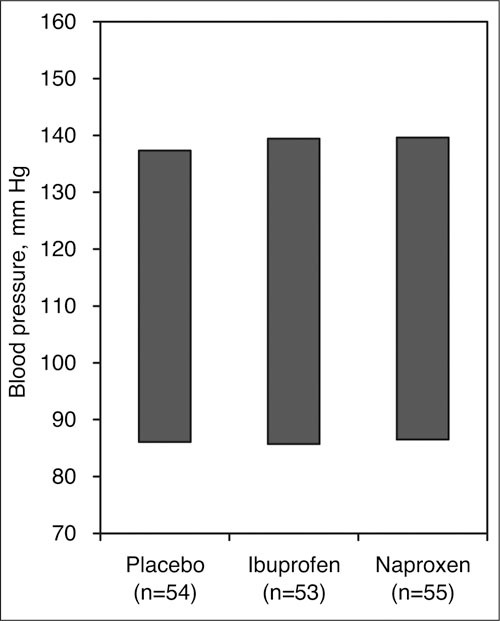

THE EFFECT OF NONSTEROIDAL ANTI‐INFLAMMATORY DRUGS ON CCB EFFICACY

Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may attenuate the antihypertensive effect of BP‐lowering drugs probably due to inhibition of renal prostaglandin production. 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 This negative drug‐drug interaction is not seen with CCBs, however. In a randomized, double‐blind, placebo controlled study of 162 hypertensive patients treated with sustained‐release verapamil 240 to 480 mg/d, patients received ibuprofen, naproxen, or placebo for 3 weeks. 117 There were no significant differences in sitting, standing, or supine BP with naproxen 500 mg dosed twice daily or ibuprofen 400 mg dosed 3 times daily compared with placebo, despite an increase in body weight with both NSAID drug therapies (Figure 12). In another study, 100 patients were treated with nicardipine 30 mg 3 times daily and then randomized to 375 mg of naproxen twice daily or placebo as add‐on therapy for 4 weeks. Although body weight increased about 0.7 kg in the naproxen‐treated subjects, there was no increase in BP. 118 In another double‐blind, crossover study, indomethacin 50 mg twice daily increased BP in patients treated with enalapril, but not in patients treated with amlodipine. 119 The cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitors celecoxib and rofecoxib did not increase systolic BP over 6 weeks in a randomized, double‐blind controlled trial of elderly hypertensive patients concomitantly receiving several different CCBs. 120 The absence of a negative BP interaction between NSAIDs, cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitors, and CCBs is a useful feature of this antihypertensive drug class.

Figure 12.

Effect of nonsteroidal drug treatment on sitting blood pressure response with verapamil. These 2 nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs did not attentuate the antihypertensive effect of verapamil after 3 weeks of treatment. Adapted with permission from Houston et al. 117

CHRONOPHARMACOLOGY

BP varies according to activity levels, especially between wakefulness and sleep, in both normotensive and hypertensive individuals. BP and heart rate are at their highest levels during the period when a hypertensive patient is awake and active (eg, work) and at their lowest levels during sleep. In most patients with essential hypertension, the BP generally declines from afternoon onward and reaches its nadir between midnight and 3 AM. This 24‐hour cycle of pressure then repeats itself and is typically reproducible in an individual as long as the activity levels for consecutive days are similar. 121 In most hypertensive patients, there is a rise in BP upon awakening that is called the morning or AM surge. 122 , 123 At this time, the rate of rise of systolic BP is approximately 3 mm Hg/h for the first 4 to 6 hours after awakening, while the rate of rise of diastolic BP is approximately 2 mm Hg/h. 123 Heart rate typically follows the same pattern as the BP; thus the rate‐pressure double product, a correlate of myocardial oxygen consumption, is increased at this time of day.

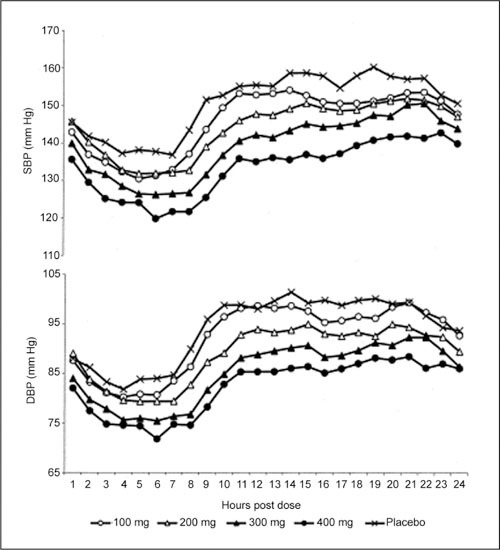

Chronotherapeutics, or delivery of a medication in concentrations that vary according to the specific physiologic need at different times during the dosing period, is a comparatively new practice in clinical medicine. Epidemiologic studies clearly document that the incidence of many cardiovascular diseases, including myocardial infarction and stroke, vary predictably in time over 24 hours (the circadian period). Diagnostic technologies using ambulatory monitoring of BP and electrocardiography have further demonstrated that there is considerable diurnal variability in the level of BP in hypertensive patients and the degree of myocardial ischemia in patients with CAD. These diagnostic techniques are also sufficiently sensitive to allow the study of the effects of varying the timing of dosing or delivery of a concentration of a drug on end points such as changes in BP, heart rate, or frequency/intensity of angina (Figure 13). 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 50 , 124 , 125

Figure 13.

Ambulatory systolic blood pressure (BP) (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) profiles produced by bedtime dosing with different doses of verapamil delivered via a spheroidal oral drug absorption system. The 200‐, 300‐, and 400‐mg doses were all effective in lowering DBP compared with placebo at all points of interest during the dosing interval. Note the minimal BP effect in the sleep hours and the significant BP reduction between 6 AM and noon (peak effect). Reproduced with permission from Smith et al. 50

The concept of chronopharmacology for BP control in the early morning hours was one with some degree of attractiveness. As the field of chronopharmacology matured, the question that continuously arose was whether a delayed‐ and sustained‐release CCB taken at bedtime would favorably impact early‐morning event rate; thus, the CONVINCE trial. 93 This study tested whether a chronotherapeutic medication timed to deliver medication from 6 AM to noon could reduce cardiovascular events. A total of 16,602 high‐risk subjects 55 years or older with stage 1 to 3 hypertension were randomized to a chronotherapeutic preparation of verapamil or traditional antihypertensive drugs (diuretic or β‐blocker). Additional drugs could be added to achieve BP control, including diuretics and ACE inhibitors. At study's end there was no difference in the combined end point of fatal and nonfatal myocardial infarction and stroke; however, the sponsor terminated this trial prematurely, which prevented a definitive answer from being reached on the issue of event‐rate reduction with nighttime verapamil administration. 93

A final consideration with nocturnally administered verapamil (or for that matter potentially any compound with chronopharmacologic delivery characteristics) is how such technology—and for that matter verapamil—is best utilized clinically. The decision to use verapamil is often based on other concomitant problems and medications. 40 In that regard, verapamil remains an effective therapy in the hypertensive patient with or without diabetes (ie, metabolic neutrality), 126 , 127 the renal failure patient (an antiproteinuric effect), 28 , 29 and the patient with left ventricular hypertrophy and/or diastolic dysfunction (ability to regress left ventricular mass and improve diastolic function). 128 , 129

The flexibility in how verapamil can be administered further extends the utility of this compound, particularly as relates to its chronopharmacologic delivery. 130 Nocturnally administered verapamil can effectively lower BP in a not insignificant number of hypertensive individuals, which shows this type delivery system to require only once‐daily administration; however, as for most antihypertensive drug classes, single‐drug therapy, even when maximally titrated, is at best only modestly effective in normalizing BP in stage I or II hypertension, which represents the majority of the hypertensive population.

The options for multidrug therapy are quite simple: either fixed‐dose combination therapy or drugs added sequentially one after another to then arrive at an effective multidrug regimen. 131 The need to retain dosing flexibility is a reason why fixed‐dose combination antihypertensive therapy is not a solution for the treatment of all hypertensive patients. For example, providing antihypertensive medication at different times (morning and night) offers an additional option on how best to control BP (and potentially end‐organ manifestations of hypertension) for a full 24 hours. 132 , 133 , 134 If this approach is taken then it is quite logical to consider antihypertensive compounds with chronopharmacologic features. 135

CLINICAL PROBLEMS WITH CCB THERAPY

Gastroesophageal Reflux. Whereas CCBs can be used for the treatment of esophageal spasm, they can also be associated with gastroesophageal reflux. 136 Gastroesophageal reflux with CCB therapy results from the decrease in lower esophageal sphincter tone with these agents. The exact incidence of gastroesophageal reflux with CCB therapy is not known, in part, since this disease can often be asymptomatic. CCB‐treated patients should be questioned periodically about new‐onset or worsening reflux symptoms. A positive response to such questioning requires that a decision be made as to the advisability of continuing CCB therapy. If therapy is continued, a dosage reduction of the CCB may result in a decrease in symptoms. On a practical basis, such patients should not receive CCBs at bedtime, which is the time when patients are more likely to experience reflux due to the supine position usual at night and the circadian pattern of increased acid production. Finally, if therapy with an H2‐receptor antagonist is considered, then cimetidine should not be used. Cimetidine, in particular among H2‐receptor antagonists, can cause serum level elevations (and potentially greater effect) for most available CCBs; this is a result of either increased bioavailability and/or decreased metabolism. 137 , 138

Polyuria. Many CCBs are reported to induce polyuria, which may also manifest as nocturia or nocturnal enuresis. 139 , 140 The polyuria seen with CCBs is to be distinguished from the natriuretic response to these compounds. 141 These urinary effects are uncommon (fewer than 1%, according to most manufacturer data), and although discomfiting, are only occasionally severe enough to warrant drug withdrawal. Cessation of the CCB is typically followed by disappearance of the polyuria/nocturia. 140 If CCB therapy is a necessary component of a treatment regimen in a patient with polyuria, then a change from a dihydropyridine to nondihydropyridine, or vice versa, and/or avoidance of nocturnal dosing can be considered.

CCB Overdose. Overdoses of CCBs are becoming more frequent and reflect an extension of the known pharmacodynamic profile of these agents, with the greatest number of cases occurring with verapamil. 142 , 143 , 144 , 145 Typical features include confusion or lethargy, hypotension, sinus node depression, and cardiac conduction defects. Symptoms may be delayed in their onset and particularly persistent if a sustained‐release preparation has been ingested. 145 Management of CCB overdose includes gut decontamination with lavage and activated charcoal, pacing if indicated, as well as IV calcium, glucagon, or other vasopressors. 146 , 147 Because of extensive protein binding, large volumes of distribution, and high endogenous clearance, neither hemodialysis nor hemoperfusion would be expected to meaningfully accelerate the removal of CCBs from patients with an overdose. The fact that hemodialysis or plasmapheresis is ineffective in removing verapamil, and hemoperfusion in removing diltiazem and desacetyl diltiazem, has been demonstrated in overdose situations. 146 , 147 , 148

Gingival Enlargement. Gingival enlargement is one of the side effects associated with the administration of several drugs. These drugs can be divided into 3 categories: anticonvulsants, CCBs, and the immunosuppressant cyclosporin. 149 The most common CCB associated with the development of gingival enlargement is nifedipine; however, this has also occurred with the administration of verapamil, felodipine, nitrendipine, diltiazem, and amlodipine. 150 , 151 , 152 The clinician should be particularly concerned with cases where there is evidence of gingival enlargement in patients taking 1 or more of these drugs, because this poses a plaque‐control problem and may affect mastication, tooth eruption, and speech, and may also present aesthetic concerns.

For patients on nifedipine, where the prevalence of gingival enlargement has been reported to be as high as 44%, other CCBs such as diltiazem and verapamil may be feasible alternatives; the prevalence of gingival enlargement associated with those drugs is less (diltiazem [20%] and verapamil [4%]). 150 , 151 , 152 Also, consideration may be given to alternative non‐CCB antihypertensive therapy, such as a diuretic, in elderly or black patients. When gingival enlargement is recognized in a CCB‐treated patient and the patient requires a CCB for continued good results (severity of hypertension or intolerance to other medications) then plaque control should be emphasized as a first step. Although the exact role played by bacterial plaque in drug‐induced gingival enlargement is unclear, there is some evidence that good oral hygiene and frequent professional removal of plaque decreases the degree of gingival enlargement and improves overall gingival health. 150

Herbal Therapies. St John's wort is known to reduce the bioavailability of verapamil in healthy subjects. The coadministration of St John's wort with verapamil significantly reduced the maximal plasma concentrations for R‐ and S‐verapamil (by 76% and 78%, respectively) and area under the concentration‐time curve (decreasing Rand S‐verapamil by 78% and 80%, respectively). Neither time‐to‐peak concentrations nor plasma half‐lives of verapamil and its active metabolite norverapamil were changed by exposure to St John's wort. 153 The probable mechanism with this drug‐drug interaction is an induction of CYP3A4‐mediated verapamil metabolism. Although other CCBs have not been similarly studied with St John's wort, there is a strong likelihood that a similar interaction would occur, since all CCBs undergo CYP3A4‐mediated elimination.

CYP3A4 Inhibition. Heterogeneity exists among the CCBs in their ability to suppress CYP3A4 activity. Verapamil and diltiazem clearly suppress activity of this P450 isozyme. This can have important and practical clinical implications. For instance, the administration of verapamil or diltiazem together with erythromycin is associated with a 5‐fold higher rate (2‐fold higher rate with erythromycin alone) of sudden cardiac death. 154 The most likely basis for this drug‐drug interaction is that verapamil or diltiazem inhibits CYP3A4 activity and erythromycin levels rise—a circumstance that can be associated with QT prolongation and, potentially, torsades de pointes.

CYP3A4 inhibition with verapamil and diltiazem can also curtail the metabolism of CYP3A4‐metabolized drugs such as eplerenone, cyclosporine, and a number of the statins (lovastatin, simvastatin, atorvastatin). 155 , 156 , 157 On the one hand, the ensuing rise in the blood levels of each of these compounds offers an economic benefit in that less drug is needed. For example, in one study, 19 patients who received simvastatin and diltiazem experienced a 33.3% decrease in cholesterol levels, compared with 116 patients not receiving diltiazem who had a 24.75% reduction in cholesterol with simvastatin. 156 In a separate study examining the pharmacokinetic interaction with diltiazem (120 mg bid for 2 weeks) and simvastatin (20 mg), the increase in the area under the curve for simvastatin was 4.8±1.7‐fold, the increase in maximum concentration was 4.1±1.8‐fold, and the increase in half‐life was 2.4±1.7‐fold. 157

Alternatively, if the interaction is not anticipated and reduction in drug dose does not occur, then drug concentration‐dependent side effects may ensue—such as hyperkalemia with eplerenone, nephrotoxicity with cyclosporine, and rhabdomyolysis with statin therapy. This interaction is one that to a degree is dose‐independent; therefore, it should be considered a possibility even with what might be considered low‐end therapeutic doses of verapamil or diltiazem.

Renovascular Disease. Soon after their release, a syndrome of functional renal insufficiency was recognized as a class effect with ACE inhibitors. This phenomenon was initially reported in patients with renal artery stenosis and a solitary kidney or in the presence of bilateral tight renal artery steno‐sis. Predisposing conditions to this process include dehydration, heart failure, NSAID use, and/or either macrovascular or microvascular renal disease. The mechanistic prompt in each of these conditions (in the untreated state) is a decrease in afferent arteriolar flow, an ensuing increase in angiotensin‐II‐mediated efferent arteriolar vasoconstriction, and, with an ACE inhibitor (treated state), a sudden dilation of the postglomerular circulation and a rapid decrease in the glomerular filtration rate.

This type of functional renal insufficiency is best treated by discontinuation of the responsible agent, careful volume expansion (if intravascular volume contraction is a contributing factor), and, if warranted on clinical grounds, evaluation for the presence of renal artery stenosis. An additional option in certain instances (where the glomerular filtration rate decrease is not excessive) is to consider CCB therapy together with an ACE inhibitor (or ARB). Preliminary data have shown that among elderly patients receiving ACE inhibitors, the use of CCBs is associated with a reduced risk of worsening renal function—presumably because of CCB‐related afferent arteriolar vasodilation. 158 The chronic use of CCBs has also been shown to be a cause of bilateral symmetric false‐positive cap‐topril renography in patients with established renal artery stenosis. 159

Peripheral Edema. Among the several dihydropyridine CCBs, there have been inconsistent findings when switching from one dihydropyridine CCB to another or when converting to different formulations of the same drug to lessen or resolve the peripheral edema. 160 , 161 , 162 Resolution of peripheral edema by drug switching (at least with the older CCBs) is unlikely to reflect fundamental biologic differences between drugs. 162 If there is a relevant difference in the biology of these compounds, it would have to be ascribed to differences in vascular permeability and/or differing effects on precapillary and postcapillary vascular resistance. There are 2 exceptions, however, to this issue of drug switching: (1) edema will diminish upon conversion from a dihydropyridine CCB to a nondihydropyridine CCB, such as verapamil or diltiazem; and (2) the newer dihydropyridine CCBs, such as lacidipine, 66 manidipine 163 , 164 and lercanidipine, 66 , 165 are reported to cause less peripheral edema. There is also some suggestion that nocturnally administered CCBs carry a reduced risk of edema development. 33 , 166

Diuretic therapy has been offered as a mode of treatment for CCB‐related peripheral edema despite the fact that this form of peripheral edema has not been shown to be related to volume overload per se. Some change in limb volume, a more precise marker of CCB‐related vasodilation effect than edema, can be demonstrated with thiazide‐type diuretics; however, the manner by which diuretic therapy may improve CCB‐related peripheral edema has not been elucidated. It is ill‐advised to routinely diurese patients with CCB‐related peripheral edema for the sole purpose of correcting the edema.

Another strategy useful for the resolution of CCB‐related edema is that of providing a venodilator drug to reduce the venous hypertension that characterizes this phenomenon. 67 , 167 Several drug classes have relevant venodilating potential and, in addition, may further reduce BP, including ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and nitrates. 168 ACE inhibitors have been the best studied of this group and have been shown in several trials to improve edema rate and severity when administered to patients with edema from a CCB. 67 , 167 Certain questions remain, however: (1) What is the optimal venodilating dose of an ACE inhibitor for a specific CCB? and (2) Do intraclass differences exist among the several ACE inhibitors currently available? Until such information becomes available, ACE inhibitors should be empirically dosed according to BP considerations and any venodilating effect accepted as a secondary benefit. It should also be appreciated that the addition of an ACE inhibitor to a CCB further reduces BP and may permit reduction in the dose of the CCB; this will also aid in resolution of peripheral edema.

ARBs should behave as ACE inhibitors in the potential for venodilation; however, limited information is available in the published literature that might allow substantiation of this hypothesis. Finally, nitrates offer some venodilating potential but require a stop/start regimen to forestall nitrate tolerance; thus, the dosing regimen becomes fairly cumbersome if their use is contemplated as a means of modifying peripheral edema.

CONCLUSIONS

A number of large, prospective, randomized, clinical outcomes trials have demonstrated that CCBs are effective and safe antihypertensive drugs and reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in treated patients. When compared with conventional antihypertensive drugs, they have demonstrated similar BP‐lowering effects and comparable reductions in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, with the exception of a higher incidence of heart failure in some studies, when compared with ACEI‐ and diuretic‐based regimens. Considering all available evidence, these drugs should be considered safe compounds for the treatment of the uncomplicated hypertensive patient. 169 , 170 , 171 CCBs are particularly effective in elderly patients and should be considered as a preferred initial medication (along with diuretics) in this large segment of the hypertensive population.

There are 2 particularly important features of CCBs: the heterogeneity of drugs in this class and its multiple delivery systems, and the potency of these compounds. There is considerable class heterogeneity, with major distinguishing features separating verapamil and diltiazem (nondihydropyridines) from drugs such as amlodipine, nifedipine, and felodipine (dihydropyridines). In addition, there are distinctions to be made as to the delivery system technology applied to patient management, with a novel nocturnal delivery system available for verapamil. Nocturnally administered antihypertensives provide significant morning coverage for the morning BP surge, which may be of particular relevance to high‐risk individuals such as the patient with hypertension, diabetes, and/or renal failure.

CCBs reduce BP in a more predictable manner than many other antihypertensive agents; however, multidrug therapy is still required for many CCB‐treated patients to reach goal. Either an ACE inhibitor or an ARB is widely viewed as the complementary second drug to be combined with a CCB—or, conversely, CCBs are excellent therapeutic additions to an ACE inhibitor and/or an ARB. Less well recognized and similarly effective are combinations of a CCB and either a diuretic or a peripheral α‐antagonist or the administration of 2 CCBs of different classes. Multidrug therapy in the management of hypertension is necessary to achieve goal BP in a high percentage of patients, and CCBs are often an important component of many multidrug regimens.

References

- 1. Nelson CR, Knapp DA. Trends in antihypertensive drug therapy of ambulatory patients by US office‐based physicians. Hypertension. 2000;36:600–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siegel D, Lopez J. Trends in antihypertensive drug use in the United States: do the JNC V recommendations affect prescribing? Fifth Joint National Commission on the Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. JAMA. 1997;278:1745–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Manolio TA, Cutler JA, Furberg CD, et al. Trends in pharmacologic management of hypertension in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:829–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Psaty BM, Manolio TA, Smith NL, et al. Time trends in high blood pressure control and the use of antihypertensive medications in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2325–2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Held PH, Yusuf S, Furberg CD. Calcium channel blockers in acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina: an overview. BMJ. 1989;299:1187–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yusuf S, Held P, Furberg C. Update of effects of calcium antagonists in myocardial infarction or angina in light of the second Danish Verapamil Infarction Trial (DAVIT‐II) and other recent studies. Am J Cardiol. 1991;67:1295–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Furberg CD, Psaty BM, Meyer JV. Nifedipine. Dose‐related increase in mortality in patients with coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1995;92:1326–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Byington RP, Craven TE, Furberg CD, et al. Isradipine, raised glycosylated haemoglobin, and risk of cardiovascular events. Lancet. 1997;350:1075–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wagenknecht LE, Furberg CD, Hammon JW, et al. Surgical bleeding: unexpected effect of a calcium antagonist. BMJ. 1995;310:776–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pahor M, Guralnik JM, Furberg CD, et al. Risk of gastrointestinal haemorrhage with calcium antagonists in hypertensive persons over 67 years old. Lancet. 1996;347:1061–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pahor M, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, et al. Calcium‐channel blockade and incidence of cancer in aged populations. Lancet. 1996;348:493–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang TJ, Ausiello JC, Stafford RS. Trends in anti‐hypertensive drug advertising, 1985–1996. Circulation. 1999;99:2055–2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group . The Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial. Major outcomes in high‐risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) [published corrections appear in JAMA. 2003;289:178 and JAMA. 2004;291:2196]. JAMA. 2002;288:2981–2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Abernethy DR, Schwartz JB. Calcium‐antagonist drugs. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1447–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Morel N, Buryi V, Feron O, et al. The action of calcium channel blockers on recombinant L‐type calcium channel alpha1‐subunits. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;125:1005–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Soldatov NM, Bouron A, Reuter H. Different voltage‐dependent inhibition by dihydropyridines of human Ca2+ channel splice variants. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10540–10543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ellenbogen KA, Dias VC, Cardello FP, et al. Safety and efficacy of intravenous diltiazem in atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:45–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McNamara RL, Tamariz LJ, Segal JB, et al. Management of atrial fibrillation: review of the evidence for the role of pharmacologic therapy, electrical cardioversion, and echocardiography. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:1018–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leenen FH, Ruzicka M, Huang BS. Central sympathoinhibitory effects of calcium channel blockers. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2001;3:314–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Krusell LR, Christensen CK, Lederballe Pedersen O. Acute natriuretic effect of nifedipine in hypertensive patients and normotensive controls–a proximal tubular effect? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;32:121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Terzoli L, Leonetti G, Pedretti R, et al. Nifedipine does not blunt the aldosterone and cardiovascular response to angiotensin II and potassium infusion in hypertensive patients. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1988;11:317–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang Z, Noll G, Luscher TF. Calcium antagonists differently inhibit proliferation of human coronary smooth muscle cells in response to pulsatile stretch and platelet‐derived growth factor. Circulation. 1993;88:832–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van Zwieten PA, van Meel JC, Timmermans PB. Pharmacology of calcium entry blockers: interaction with vascular alpha‐adrenoceptors. Hypertension. 1983;5:II8–II17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weinstein DB, Heider JG. Antiatherogenic properties of calcium antagonists. State of the art. Am J Med. 1989;86:27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nayler WG. Vascular injury: mechanisms and manifestations. Am J Med. 1991;90:8S–13S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Borhani NO, Mercuri M, Borhani PA, et al. Final outcome results of the Multicenter Isradipine Diuretic Atherosclerosis Study (MIDAS). A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;276:785–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zanchetti A, Rosei EA, Dal Palu C, et al. The Verapamil in Hypertension and Atherosclerosis Study (VHAS): results of long‐term randomized treatment with either verapamil or chlorthalidone on carotid intima‐media thickness. J Hypertens. 1998;16:1667–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Griffin KA, Picken MM, Bakris GL, et al. Class differences in the effects of calcium channel blockers in the rat remnant kidney model. Kidney Int. 1999;55:1849–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bakris GL, Weir MR, DeQuattro V, et al. Effects of an ACE inhibitor/calcium antagonist combination on proteinuria in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 1998;54:1283–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pedrinelli R, Salvetti A. Heterogeneous interference of nicardipine, verapamil, and diltiazem with forearm arteriolar responsiveness to adrenergic stimulation in hypertensive patients. Am Heart J. 1991;122:342–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Elliott WJ, Prisant LM. Controlled‐release formulations of calcium antagonist. In: Epstein M, ed. Calcium Antagonists in Clinical Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Hanley & Belfus Inc; 2002:139–150. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Herbette LG, Vecchiarelli M, Sartani A, et al. Lercanidipine: short plasma half‐life, long duration of action and high cholesterol tolerance. Updated molecular model to rationalize its pharmacokinetic properties. Blood Press Suppl. 1998;2:10–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Neutel JM, Alderman M, Anders RJ, et al. Novel delivery system for verapamil designed to achieve maximal blood pressure control during the early morning. Am Heart J. 1996;132:1202–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. White WB, Anders RJ, MacIntyre JM, et al. Nocturnal dosing of a novel delivery system of verapamil for systemic hypertension. Verapamil Study Group. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76:375–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Prisant LM, Devane JG, Butler J. A steady‐state evaluation of the bioavailability of chronotherapeutic oral drug absorption system verapamil PM after nighttime dosing versus immediate‐acting verapamil dosed every eight hours. Am J Ther. 2000;7:345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sista S, Lai JC, Eradiri O, et al. Pharmacokinetics of a novel diltiazem HCl extended‐release tablet formulation for evening administration. J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;43:1149–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McAllister RG Jr, Schloemer GL, Hamann SR. Kinetics and dynamics of calcium entry antagonists in systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 1986;57:16D–21D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Murdoch D, Heel RC. Amlodipine. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic use in cardiovascular disease. Drugs. 1991;41:478–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sica DA, Gehr TWB. Calcium channel blockers and end‐stage renal disease: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2003;12:123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McTavish D, Sorkin EM. Verapamil. An updated review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic use in hypertension. Drugs. 1989;38:19–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Prisant LM. Calcium antagonists. In: Hypertension: A Companion to Brenner and Rector's The Kidney. Oparil S, Weber M, eds. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2005:683–704. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Weir MR, Zachariah P. Verapamil. In: Messerli F, ed. Cardiovascular Drug Therapy. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1996;915–930. [Google Scholar]