Abstract

The 52‐week Therapeutic Arthritis Research and Gastrointestinal Event Trial (TARGET) investigated the gastrointestinal and cardiovascular safety profile of lumiracoxib 400 mg once daily compared with 2 traditional nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): ibuprofen 800 mg 3 times daily and naproxen 500 mg twice daily. Data from TARGET were analyzed to examine the effect of lumiracoxib compared with ibuprofen and naproxen on blood pressure (BP), incidence of de novo and aggravated hypertension, prespecified edema events, and congestive heart failure. Lumiracoxib resulted in smaller changes in BP as early as week 4. Least‐squares mean change from baseline at week 4 for systolic BP was +0.57 mm Hg with lumiracoxib compared with +3.14 mm Hg with ibuprofen (P<.0001) and +0.43 with lumiracoxib compared with +1.80 mm Hg with naproxen (P<.0001). In conclusion, the use of lumiracoxib and traditional NSAIDs results in differing BP changes; these might be of clinical relevance.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common condition that affects 18% of women and 10% of men worldwide. 1 Lumiracoxib is a structurally distinct, selective cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) inhibitor for the management of OA and acute pain. 2

Concerns have been raised regarding the blood pressure (BP) changes with nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Both COX isoforms contribute to the regulation of normal renal function. 3 , 4 COX‐2 is thought to play a role in salt and water homeostasis, 4 with its inhibition leading to renovascular vasoconstriction, decreased renal blood flow, and salt and water retention. These factors may lead to elevation of BP, aggravation of existing hypertension, and/or edema. It has been hypothesized that effects on BP may contribute to increased cardiovascular risk in NSAID‐treated patients since even small increases in BP can have an impact on cardiovascular events. 5 Mean changes in BP have been reported previously for lumiracoxib 400 mg (4 times the recommended dose in OA) compared with the NSAIDs naproxen 500 mg twice daily and ibuprofen 800 mg 3 times daily over 52 weeks in the Therapeutic Arthritis Research and Gastrointestinal Event Trial (TARGET); these data indicate less effect on BP with lumiracoxib compared with NSAIDs. 6 To investigate these findings further, we examined the effect of lumiracoxib compared with the NSAIDs ibuprofen and naproxen on BP in TARGET after 4 weeks of treatment and at predefined time points. Furthermore, the incidence of de novo and aggravated hypertension, prespecified edema adverse events, congestive heart failure, and weight gain were also evaluated.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The methodology from TARGET has been presented in detail elsewhere 7 and is summarized here.

Study Design

TARGET was a 52‐week, international, multi‐center, randomized study. Lumiracoxib 400 mg daily was compared with ibuprofen 800 mg 3 times a day (ibuprofen substudy) and naproxen 500 mg twice daily (naproxen substudy). The primary end points have been reported previously. 6 , 8 The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committees in participating countries. All participants provided informed consent.

Patients

Men and women aged 50 years or older were recruited. Patients were required to have a clinical diagnosis of OA of the hip, knee, hand, or spine with a baseline pain assessment of at least moderate pain in the affected joint and anticipated need for treatment for at least 52 weeks. Patients at high risk for coronary heart disease or requiring secondary prevention were included in the study only if low‐dose aspirin (75–100 mg) was initiated at least 3 months before screening. Patients with a history of myocardial infarction, stroke, coronary artery bypass graft, invasive coronary revascularization or new‐onset angina were excluded only if one of these events had occurred within the previous 6 months. Patients with electrocardiographic evidence of silent myocardial ischemia; severe congestive heart failure; hepatic, renal, or blood coagulation disorders; or anemia were also excluded from the study.

In line with clinical practice, antihypertensive medication could be initiated or changed at any time during the study.

Monitoring

Investigators were required to report all suspected occurrences of a series of gastrointestinal (GI), cardiovascular, and liver events, which were then independently adjudicated under blinded conditions. 7

Assessments

Patients made routine visits at baseline and after 4, 13, 20, 26, 39, and 52 weeks or until withdrawal, with a follow‐up telephone contact 4 weeks after exit from the study. Efficacy, adverse events, and laboratory data were recorded at each visit. Pain control was assessed by OA pain intensity; the patient's and physician's global assessment of disease activity were measured on 5‐point Likert scales. Office cuff BP measurements were performed at screening, baseline, and weeks 4, 13, 26, 39, and 52. BP was measured once at each visit after 5 minutes of rest, using the same arm, the same device (each investigator's usual office cuff sphygmomanometer), and whenever possible at the same time of day (preferably between 8:00 am and 11:00 am) as on a previous visit. Measurement of BP occurred before dosing at the baseline visit and after dosing at subsequent visits. Changes in systolic and diastolic office cuff BP were calculated for every patient at each study visit compared with baseline values. Changes in BP were then compared between treatment groups.

The following assessments were also used to evaluate the BP changes of lumiracoxib compared with NSAIDs:

-

•

Incidence of the following adverse events: de novo hypertension (defined as investigator‐reported occurrence of hypertension in patients without a history of hypertension at baseline); aggravated hypertension (defined as investigator‐reported increases in hypertension severity in patients with a medical history of hypertension at baseline [ie, further increase in BP in hypertensive patients]). A formal BP definition for hypertension was not specified in the protocol, and investigators diagnosed and reported hypertension in line with their accepted local/national guidelines and standard clinical practice. Systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg is the generally accepted definition of hypertension by international guidelines 9 , 10 and, thus, may have been used by investigators.

-

•

Incidence of edema: prespecified edema adverse events (Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities‐preferred terms: anasarca, face edema, gravitational edema, localized edema, peripheral edema, periorbital edema, pitting edema, or swelling) reported by the treating physician.

-

•

Incidence of congestive heart failure (congestive heart failure data were taken from investigator‐reported adverse events matching to preferred terms of cardiac failure, cardiac failure chronic, and cardiac failure congestive. Congestive heart failure data were not, however, adjudicated, and analyses were completed post hoc).

-

•

Laboratory biochemical tests were used to monitor renal function; these included serum creatinine, calculated creatinine clearance, serum potassium, and urine protein measurements. Major renal events were defined as serum creatinine increase from baseline ≥100% and/or proteinuria ≥3.0 g/L (by urine dipstick). Patients with serum creatinine levels >1.25 times the upper limit of normal were excluded from the study. The Cockcroft‐Gault formula was used to calculate glomerular filtration rate.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses of BP changes from baseline (at different time points) used analysis of covariance models, with baseline values, sex, and age as covariates. Time windows for week 4 and month 12 were defined as study days 2 through 59 and ≥319, respectively. The week 4 time point was selected to reflect the time when most patients were still taking their allocated therapy, whereas the month 12 time point was the end of study. Between‐treatment group differences for de novo and aggravated (more severe) hypertension were assessed with Cox proportional hazards models (with age as a covariate), including estimation of hazard ratios and their associated 95% confidence intervals. Fisher's exact tests were used to compare the incidence of edema and congestive heart failure between treatment groups.

The sample size was based on the study's primary objective, which was to demonstrate a possible significant difference in the time‐to‐event distribution of upper GI complications between lumiracoxib and NSAIDs (naproxen and ibuprofen combined). 6

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and Pain Control

TARGET was completed in 32 countries; 18,244 patients received at least one dose of study medication (safety‐evaluable population), with 9,117 patients receiving lumiracoxib and 9,127 patients receiving NSAIDs. A patient flow diagram has been published previously. 6 , 8 Patient characteristics were similar between treatment groups; the data for the combined substudies are provided in Table I; data for each substudy have been published. 6 Baseline BP values were similar between treatment groups regardless of hypertensive status and/or receiving antihypertensive treatment (Table I). Pain control, as assessed by OA pain intensity, was comparable between treatment groups at week 4 and subsequent visits (Table II).

Table I.

Patient Demographics and Baseline Disease Characteristics

| Lumiracoxib (n=9117) | NSAIDs (n=9127) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 63.5±8.37 | 63.4±8.35 |

| Female | 6963 (76.4) | 6970 (76.4) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.6±5.70 | 29.5±5.64 |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 6892 (75.6) | 6846 (75.0) |

| Hispanic | 1476 (16.2) | 1514 (16.6) |

| African American | 187 (2.1) | 190 (2.1) |

| Other | 562 (6.2) | 577 (6.3) |

| Low‐dose aspirin use | 2167 (23.8) | 2159 (23.7) |

| At high CV riska or with a CCV history | 1141 (12.5) | 1066 (11.7) |

| Dyslipidemia at baseline | 1829 (20.1) | 1834 (20.1) |

| Hyperlipidemia at baseline | 509 (5.6) | 495 (5.4) |

| Diabetes at baseline | 744 (8.2) | 675 (7.4) |

| Normotensive and no hypertensive treatment | ||

| No. (%) | 4434 (48.6) | 4612 (50.5) |

| SBP | 128.0±14.7 | 128.1±14.6 |

| DBP | 78.2±8.5 | 77.9±8.4 |

| Normotensive and hypertensive treatment | ||

| No. (%) | 464 (5.1) | 454 (5.0) |

| SBP | 128.8±14.2 | 130.0±14.5 |

| DBP | 77.5±9.2 | 77.3±8.0 |

| Hypertensive and no hypertensive treatment | ||

| No. (%) | 343 (3.8) | 336 (3.7) |

| SBP | 137.9±15.2 | 138.2±16.4 |

| DBP | 83.6±8.5 | 82.8±9.7 |

| Hypertensive and hypertensive treatment | ||

| No. (%) | 3876 (42.5) | 3725 (40.8) |

| SBP | 137.4±15.3 | 138.1±15.9 |

| DBP | 81.8±8.7 | 82.0±9.1 |

| Concomitant antihypertensive medicationb | ||

| No. (%) | 4340 (47.6) | 4179 (45.8) |

| Monotherapyc | 2154 (23.6) | 2073 (22.7) |

| Combination therapyc | 2134 (23.4) | 2064 (22.6) |

| β‐Blocker, selective | 949 (10.4) | 893 (9.8) |

| β‐Blocker, nonselective | 201 (2.2) | 215 (2.4) |

| ACE inhibitor, plain | 1554 (17.0) | 1469 (16.1) |

| ACE inhibitor and diuretic | 231 (2.5) | 203 (2.2) |

| Angiotensin II receptor blocker, plain | 334 (3.7) | 347 (3.8) |

| Angiotensin II receptor blocker and diuretic | 167 (1.8) | 150 (1.6) |

| Dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker | 741 (8.1) | 712 (7.8) |

| Thiazide diuretic, plain | 459 (5.0) | 427 (4.7) |

| Sulfonamide diuretic, plain | 447 (4.9) | 423 (4.6) |

| Nitrates | 286 (3.1) | 244 (2.7) |

| Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; BMI, body mass index; CCV, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular; CV, cardiovascular; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs; SBP, systolic blood pressure. Values are mean ± SD or No. (%). aAs defined in the US National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Framingham Heart Study risk algorithm. bDrugs taken before randomization (not all antihypertensive classes are listed. The 5 most commonly used antihypertensive classes are listed along with some other classes and combinations of interest). cTreatment codes for antihypertensive treatment that did not make a clear distinction between monotherapy and combination therapy were not included. | ||

Table II.

OA Pain Intensity (Assessed on a 5‐point Likert Scale) by Visit in TARGET

| Lumiracoxib n=9117 | NSAIDs n=9127 | Lumiracoxib n=4741 | Naproxen n=4730 | Lumiracoxib n=4376 | Ibuprofen n=4397 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||||||

| None | 4 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Mild | 40 (0.4) | 39 (0.4) | 20 (0.4) | 23 (0.5) | 20 (0.5) | 16 (0.4) |

| Moderate | 4288 (47.0) | 4269 (46.8) | 2282 (48.1) | 2209 (46.7) | 2006 (45.9) | 2060 (46.9) |

| Severe | 4214 (46.2) | 4247 (46.5) | 2169 (45.7) | 2207 (46.7) | 2045 (46.8) | 2040 (46.4) |

| Extreme | 569 (6.2) | 570 (6.2) | 269 (5.7) | 290 (6.1) | 300 (6.9) | 280 (6.4) |

| Week 4 | ||||||

| None | 25 (3.2) | 39 (3.7) | 8 (2.1) | 22 (4.3) | 17 (4.1) | 17 (3.1) |

| Mild | 131 (16.6) | 176 (16.6) | 66 (17.6) | 95 (18.5) | 65 (15.6) | 81 (14.8) |

| Moderate | 312 (39.4) | 410 (38.6) | 140 (37.4) | 204 (39.7) | 172 (41.2) | 206 (37.7) |

| Severe | 260 (32.9) | 371 (35.0) | 136 (36.4) | 172 (33.5) | 124 (29.7) | 199 (36.4) |

| Extreme | 63 (8.0) | 65 (6.1) | 24 (6.4) | 21 (4.1) | 39 (9.4) | 44 (8.0) |

| Week 13 | ||||||

| None | 614 (7.7) | 553 (7.2) | 313 (7.5) | 277 (6.8) | 301 (7.9) | 276 (7.5) |

| Mild | 2806 (35.1) | 2740 (35.5) | 1478 (35.2) | 1493 (36.9) | 1328 (35.0) | 1247 (34.0) |

| Moderate | 3399 (42.6) | 3288 (42.6) | 1797 (42.8) | 1694 (41.9) | 1602 (42.2) | 1594 (43.5) |

| Severe | 1038 (13.0) | 1009 (13.1) | 562 (13.4) | 532 (13.1) | 476 (12.6) | 477 (13.0) |

| Extreme | 129 (1.6) | 125 (1.6) | 44 (1.0) | 51 (1.3) | 85 (2.2) | 74 (2.0) |

| Week 26 | ||||||

| None | 686 (9.9) | 653 (9.9) | 334 (9.1) | 340 (9.6) | 352 (10.9) | 313 (10.2) |

| Mild | 2604 (37.6) | 2555 (38.7) | 1411 (38.3) | 1428 (40.4) | 1193 (36.8) | 1127 (36.7) |

| Moderate | 2751 (39.7) | 2552 (38.6) | 1463 (39.7) | 1331 (37.6) | 1288 (39.8) | 1221 (39.8) |

| Severe | 794 (11.5) | 762 (11.5) | 433 (11.7) | 395 (11.2) | 361 (11.1) | 367 (12.0) |

| Extreme | 91 (1.3) | 85 (1.3) | 46 (1.2) | 45 (1.3) | 45 (1.4) | 40 (1.3) |

| Week 52 | ||||||

| None | 805 (13.8) | 776 (13.9) | 393 (12.6) | 395 (13.0) | 412 (15.1) | 381 (14.9) |

| Mild | 2390 (40.9) | 2293 (41.0) | 1283 (41.3) | 1257 (41.3) | 1107 (40.5) | 1036 (40.5) |

| Moderate | 2010 (34.4) | 1928 (34.5) | 1090 (35.1) | 1045 (34.4) | 920 (33.7) | 883 (34.6) |

| Severe | 566 (9.7) | 552 (9.9) | 314 (10.1) | 321 (10.6) | 252 (9.2) | 231 (9.0) |

| Extreme | 69 (1.2) | 46 (0.8) | 29 (0.9) | 22 (0.7) | 40 (1.5) | 24 (0.9) |

| Abbreviations: NSAIDs, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs; OA, osteoarthritis; TARGET, Therapeutic Arthritis Research and Gastrointestinal Event Trial. Values are No. (%). | ||||||

Mean Changes in Diastolic and Systolic BP

BP changes were significantly less with lumiracoxib compared with NSAIDs as early as week 4 and at all study visits over the 52‐week treatment period (data not shown) (BP changes from baseline for individual drugs at serial visits are presented in Table III). At week 4, least‐squares mean (LSM) change from baseline for systolic BP was +0.50 mm Hg for lumiracoxib and +2.44 mm Hg for NSAIDs (P<.0001). The respective values at month 12 were +1.28 mm Hg for lumiracoxib and +2.49 mm Hg for NSAIDs (P<.0001). For diastolic BP, LSM change from baseline at week 4 was +0.02 mm Hg for lumiracoxib and 0.72 mm Hg for NSAIDs (P<.0001); at month 12, LSM change from baseline was +0.02 mm Hg and +0.56 mm Hg, respectively (P=.0007).

Table III.

Blood Pressure Change From Baseline in the Ibuprofen and Naproxen Substudies of TARGET

| Visit | Treatment Group | No. | Baseline, Mean | CFB, LSM | Treatment Difference in CFB, LSM (95% CI) | P Value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ibuprofen Substudy | ||||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | ||||||

| Baseline | Lumiracoxib | 4312 | 131.0 | |||

| Ibuprofen | 4331 | 131.1 | ||||

| Week 4 | Lumiracoxib | 4292 | 131.0 | 0.57 | −2.56 (−3.1, −2.0) | <.0001 |

| Ibuprofen | 4302 | 131.1 | 3.14 | |||

| Month 3 | Lumiracoxib | 3787 | 131.0 | 0.68 | −2.47 (−3.1, −1.8) | <.0001 |

| Ibuprofen | 3671 | 130.9 | 3.16 | |||

| Month 6 | Lumiracoxib | 3238 | 131.0 | 0.96 | −2.20 (−2.9, −1.5) | <.0001 |

| Ibuprofen | 3064 | 130.8 | 3.16 | |||

| Month 9 | Lumiracoxib | 2963 | 130.9 | 0.59 | −1.97 (−2.7, −1.2) | <.0001 |

| Ibuprofen | 2780 | 130.8 | 2.55 | |||

| Month 12 | Lumiracoxib | 2733 | 130.9 | 1.40 | −1.31 (−2.1, −0.6) | .0007 |

| Ibuprofen | 2553 | 130.6 | 2.72 | |||

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | ||||||

| Baseline | Lumiracoxib | 4312 | 79.2 | |||

| Ibuprofen | 4331 | 79.0 | ||||

| Week 4 | Lumiracoxib | 4291 | 79.2 | 0.07 | −0.98 (−1.3, −0.6) | <.0001 |

| Ibuprofen | 4302 | 79.0 | 1.05 | |||

| Month 3 | Lumiracoxib | 3787 | 79.3 | 0.29 | −1.03 (−1.4, −0.6) | <.0001 |

| Ibuprofen | 3671 | 79.0 | 1.31 | |||

| Month 6 | Lumiracoxib | 3238 | 79.3 | 0.42 | −0.73 (−1.1, −0.3) | .0005 |

| Ibuprofen | 3064 | 79.0 | 1.15 | |||

| Month 9 | Lumiracoxib | 2962 | 79.3 | 0.23 | −0.53 (−1.0, −0.1) | .0158 |

| Ibuprofen | 2781 | 79.0 | 0.77 | |||

| Month 12 | Lumiracoxib | 2733 | 79.3 | 0.18 | −0.66 (−1.1, −0.2) | .0041 |

| Ibuprofen | 2553 | 78.9 | 0.84 | |||

| Naproxen Substudy | ||||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | ||||||

| Baseline | Lumiracoxib | 4678 | 133.8 | |||

| Naproxen | 4661 | 134.1 | ||||

| Week 4 | Lumiracoxib | 4655 | 133.8 | 0.43 | −1.37 (−1.9, −0.8) | <.0001 |

| Naproxen | 4628 | 134.1 | 1.80 | |||

| Month 3 | Lumiracoxib | 4195 | 133.5 | −0.14 | −1.25 (−1.9, −0.6) | <.0001 |

| Naproxen | 4036 | 134.0 | 1.11 | |||

| Month 6 | Lumiracoxib | 3687 | 133.4 | 0.70 | −1.08 (−1.7, −0.4) | .0015 |

| Naproxen | 3537 | 133.8 | 1.78 | |||

| Month 9 | Lumiracoxib | 3336 | 133.1 | 1.31 | −1.14 (−1.8, −0.5) | .0011 |

| Naproxen | 3251 | 133.8 | 2.45 | |||

| Month 12 | Lumiracoxib | 3111 | 133.0 | 1.20 | −1.09 (−1.8, −0.4) | .0029 |

| Naproxen | 3039 | 133.8 | 2.29 | |||

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | ||||||

| Baseline | Lumiracoxib | 4678 | 80.5 | |||

| Naproxen | 4661 | 80.4 | ||||

| Week 4 | Lumiracoxib | 4655 | 80.5 | −0.02 | −0.44 (−0.8, −0.1) | .0058 |

| Naproxen | 4628 | 80.5 | 0.42 | |||

| Month 3 | Lumiracoxib | 4195 | 80.4 | −0.39 | −0.49 (−0.8, −0.1) | .0064 |

| Naproxen | 4036 | 80.6 | 0.09 | |||

| Month 6 | Lumiracoxib | 3687 | 80.5 | −0.18 | −0.53 (−0.9, −0.1) | .0081 |

| Naproxen | 3537 | 80.7 | 0.35 | |||

| Month 9 | Lumiracoxib | 3336 | 80.3 | 0.07 | −0.72 (−1.1, −0.3) | .0005 |

| Naproxen | 3251 | 80.7 | 0.79 | |||

| Month 12 | Lumiracoxib | 3111 | 80.3 | −0.11 | −0.41 (−0.8, 0.0) | .0566 |

| Naproxen | 3039 | 80.7 | 0.30 | |||

| Abbreviations: CFB, change from baseline; CI, confidence interval; LSM, least‐squares mean; TARGET, Therapeutic Arthritis Research and Gastrointestinal Event Trial. a P value for treatment difference from general linear model (including baseline blood pressure, age [continuous], sex, study and treatment factors). | ||||||

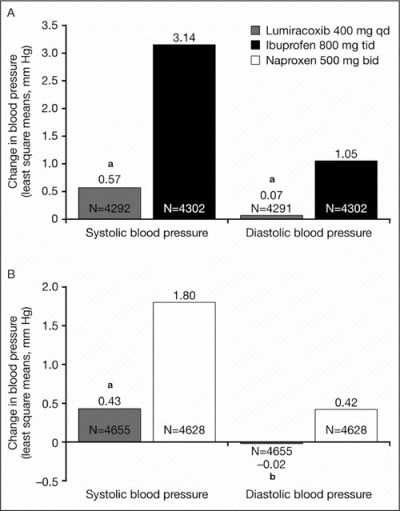

Comparison with Ibuprofen

The pattern of changes in systolic and diastolic BP was similar to that observed for the overall study: changes from baseline were significantly smaller for lumiracoxib compared with ibuprofen after 4 weeks of treatment (Figure 1A, Table III) and at all other study visits over the 52‐week treatment period (Table III). Similarly, at month 12, lumiracoxib had less of an impact on BP compared with ibuprofen (Table III).

Figure 1.

Change from baseline in systolic and diastolic blood pressure at 4 weeks for (A) lumiracoxib and ibuprofen in the overall population and (B) lumiracoxib and naproxen in the overall population. aP<.0001; bP=.0058. qd indicates once daily; tid, 3 times daily; bid, twice daily.

Comparison with Naproxen

The pattern of changes in systolic and diastolic BP was similar to that observed for the overall study: changes from baseline were significantly smaller for lumiracoxib compared with naproxen after 4 weeks of treatment (Figure 1B, Table III) and at all other study visits over the 52‐week treatment period except for diastolic BP at month 12, when the numerical advantage was still present but did not reach statistical significance (Table III).

Changes in Diastolic and Systolic BP in Different Patient Populations

Effects on BP were consistent across most subgroups investigated, including age (Table III), sex, the presence of hypertension at baseline, and the type of antihypertensive medication.

Age and Hypertension

The changes in systolic and diastolic BP with lumiracoxib and naproxen at week 4 were consistent across all age groups (≤64 years; 65–74 years; ≥75 years) and followed the overall trend; lumiracoxib had a more favorable impact on BP when compared with naproxen (Table IV). Similarly, the changes in systolic and diastolic BP with lumiracoxib and ibuprofen were consistent across all age groups at week 4 (Table IV). Thus, lumiracoxib had a significantly lesser effect on systolic BP at all age groups than the NSAIDs naproxen and ibuprofen (Table IV).

Table IV.

Blood Pressure Change from Baseline by Age at Week 4

| Ibuprofen Substudy | Total No. | CFB, LSM | Total No. | CFB, LSM | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lumiracoxib 400 mg Once Daily | Ibuprofen 800 mg 3 Times Daily | ||||

| Systolic blood pressure | |||||

| Age, y | |||||

| ≤64 | 2471 | 0.73 | 2475 | 3.28 | <.0001 |

| 65–74 | 1362 | 0.35 | 1361 | 3.01 | <.0001 |

| ≥75 | 459 | 0.38 | 466 | 2.65 | .0190 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | |||||

| Age, y | |||||

| ≤64 | 2470 | 0.12 | 2475 | 1.10 | <.0001 |

| 65–74 | 1362 | 0.17 | 1361 | 1.22 | .0006 |

| ≥75 | 459 | −0.51 | 466 | 0.17 | .1927 |

| Naproxen Substudy | Lumiracoxib 400 mg Once Daily | Naproxen 500 mg Twice Daily | |||

| Systolic blood pressure | |||||

| Age, y | |||||

| ≤64 | 2566 | 0.90 | 2577 | 1.97 | .0027 |

| 65–74 | 1589 | −0.22 | 1545 | 1.53 | .0002 |

| ≥75 | 500 | 0.08 | 506 | 1.88 | .0475 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | |||||

| Age, y | |||||

| ≤64 | 2566 | 0.23 | 2577 | 0.74 | .0164 |

| 65–74 years | 1589 | −0.25 | 1545 | −0.04 | .4447 |

| ≥75 | 500 | −0.55 | 506 | 0.25 | .1196 |

| Abbreviations: CFB, change from baseline; LSM, least‐squares mean. | |||||

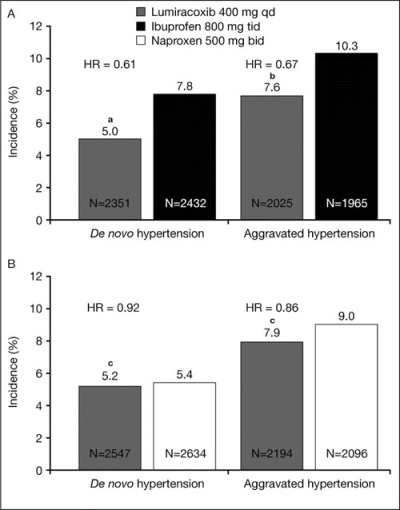

De Novo Hypertension

Lumiracoxib was associated with a significantly lower incidence of de novo hypertension than ibuprofen (5.0% vs 7.8%, respectively; P<.0001), as shown in Figure 2A. There was a significantly lower incidence of de novo hypertension for lumiracoxib compared with ibuprofen in the subgroup of patients aged 64 years or younger and in patients aged 65 to 74 years, but not in patients 75 years or older (Table V).

Figure 2.

Incidence of de novo and aggravated hypertension for (A) lumiracoxib compared with ibuprofen and (B) lumiracoxib compared with naproxen. aP<.0001; bP<.0002; cnot significant (P=.4804 for de novo hypertension; P=.1464 for aggravated hypertension). qd indicates once daily; tid, 3 times daily; bid, twice daily; HR, hazard ratio.

Table V.

Incidence of De Novo and Aggravated Hypertension by Age Group

| Total No. | Incidence, No. (%) | Total No. | Incidence, No. (%) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ibuprofen Substudy | Lumiracoxib 400 mg Once Daily | Ibuprofen 800 mg 3 Times Daily | ||||

| De novo hypertension | ||||||

| Age, y | ||||||

| ≤64 | 1527 | 77 (5.04) | 1574 | 113 (7.18) | 0.67 (0.50, 0.90) | .0067 |

| 65–74 | 643 | 27 (4.20) | 670 | 66 (9.85) | 0.40 (0.26, 0.63) | <.0001 |

| ≥75 | 181 | 14 (7.73) | 188 | 10 (5.32) | 1.40 (0.62, 3.17) | .4159 |

| Aggravated hypertension | ||||||

| Age, y | ||||||

| ≤64 | 1000 | 76 (7.60) | 962 | 103 (10.71) | 0.66 (0.49, 0.88) | .0056 |

| 65–74 | 742 | 57 (7.68) | 719 | 78 (10.85) | 0.65 (0.46, 0.91) | .0121 |

| ≥75 | 283 | 20 (7.07) | 284 | 22 (7.75) | 0.82 (0.45, 1.50) | .5112 |

| Naproxen Substudy | Lumiracoxib 400 mg Once Daily | Naproxen 500 mg Twice Daily | ||||

| De novo hypertension | ||||||

| Age, y | ||||||

| ≤64 | 1566 | 68 (4.34) | 1651 | 76 (4.60) | 0.92 (0.66, 1.27) | .5989 |

| 65–74 | 768 | 48 (6.25) | 759 | 51 (6.72) | 0.89 (0.60, 1.31) | .5444 |

| ≥75 | 213 | 16 (7.51) | 224 | 14 (6.25) | 1.05 (0.51, 2.16) | .8896 |

| Aggravated hypertension | ||||||

| Age, y | ||||||

| ≤64 | 1044 | 63 (6.03) | 981 | 91 (9.28) | 0.64 (0.47, 0.89) | .0068 |

| 65–74 | 852 | 90 (10.56) | 821 | 73 (8.89) | 1.15 (0.85, 1.57) | .3629 |

| ≥75 | 298 | 20 (6.71) | 294 | 25 (8.50) | 0.77 (0.43, 1.38) | .3796 |

| Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval. De novo (new‐onset) hypertension = investigator‐reported adverse event of hypertension in patients without a history of hypertension at baseline. Aggravated hypertension = investigator‐reported adverse event of hypertension (ie, further increased blood pressure) in patients with a history of hypertension at baseline. | ||||||

The incidence of de novo hypertension was, however, similar for lumiracoxib and naproxen (5.2% vs 5.4%, respectively), as shown in Figure 2B. There were no significant differences for the incidence of de novo hypertension for lumiracoxib compared with naproxen in the various age subgroups (Table V).

Aggravated Hypertension

Lumiracoxib was associated with a significantly lower incidence of aggravated hypertension compared with ibuprofen (7.6% vs 10.3%, respectively; P<.0002), as shown in Figure 2A. There was a significantly lower incidence of aggravated hypertension for lumiracoxib compared with ibuprofen in the subgroups of patients aged 64 years or younger and 65 to 74 years, but not in the 75 years or older subgroup (Table V).

The incidence of aggravated (ie, further increase in BP in hypertensive patients) hypertension was not significantly different for lumiracoxib and naproxen (7.9% vs 9.0%, respectively), as shown in Figure 2B. There was a significantly lower incidence of aggravated hypertension for lumiracoxib compared with naproxen in the subgroup of patients aged 64 years or younger, but not in those aged 65 to 74 years or 75 years or older (Table V).

Edema

There were no significant differences in the incidence of edema between lumiracoxib (4.96%) and ibuprofen (5.57%; P=.2139) or lumiracoxib (4.53%) and naproxen at the end of the study (4.25%; P=.5147).

Congestive Heart Failure

Lumiracoxib was associated with a numerically lower incidence of congestive heart failure (as assessed by investigator‐reported adverse events) than NSAIDs, although this did not achieve statistical significance. At week 4, the incidence was 0% with lumiracoxib compared with 0.07% with ibuprofen (P=.2499) and 0.02% with lumiracoxib compared with 0.08% for naproxen (P=.2181). At end of study, the cumulative incidence was 0.27% with lumiracoxib compared with 0.34% with ibuprofen (P=.7007) and 0.21% with lumiracoxib vs 0.34% for naproxen (P=.2466).

Renal Adverse Events

Overall, renal and urinary adverse events occurred in a similar proportion of patients taking lumiracoxib (3.1%, n=283) and NSAIDs (2.9%, n=261). There were also no statistically significant differences in the incidence of major renal events (predefined as a 100% increase in serum creatinine from baseline and/or proteinuria ≥300 mg/dL) between treatment groups, irrespective of aspirin use. In the overall population, major renal events occurred in 0.51% (n=46) and 0.37% (n=33) of patients taking lumiracoxib and NSAIDs, respectively (hazard ratio, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 0.86–2.10). The proportion of patients with newly occurring proteinuria (urinary protein ≥1.0 g/L [100 mg/dL] by urine dipstick test) was similar in the lumiracoxib and NSAID groups (1.8 and 2.1%, respectively).

Overall, during the study, a non‐statistically significant greater proportion of lumiracoxib than NSAID patients had lower creatinine clearance (Table VI). Serum potassium >5.5 mmol/L occurred in 348 (3.9%) and 338 (3.8%) patients receiving lumiracoxib and NSAIDs, respectively.

Table VI.

Incidence of Creatinine Clearance Levels at Any Time Post‐Baseline During the Study (Safety Population)

| Overall | Naproxen Substudy | Ibuprofen Substudy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lumiracoxib n=8948 | NSAIDs n=8939 | Lumiracoxib n=4656 | Naproxen n=4630 | Lumiracoxib n=4292 | Ibuprofen n=4309 | |

| <81 mL/min | 6740 (75.3) | 6567 (73.5) | 3552 (76.3) | 3457 (74.7) | 3188 (74.3) | 3110 (72.2) |

| <50 mL/min | 1481 (16.6) | 1385 (15.5) | 776 (16.7) | 717 (15.5) | 705 (16.4) | 668 (15.5) |

| <30 mL/min | 96 (1.1) | 80 (0.9) | 52 (1.1) | 28 (0.6) | 44 (1.0) | 52 (1.2) |

| >25% Decrease from baseline | 747 (8.4) | 486 (5.4) | 356 (7.6) | 193 (4.2) | 391 (9.1) | 293 (6.8) |

| Values are No. (%). Creatinine clearance calculated by Cockroft‐Gault and excluding patients with creatinine clearance >200 mL/min at baseline. | ||||||

DISCUSSION

The effects on BP of selective COX‐2 inhibitors and NSAIDs might be an important consideration when determining which treatment to prescribe, since it could impact current BP control and possibly, in the long term, cardiovascular outcomes.

These analyses from TARGET indicate that the use of lumiracoxib has less of an effect on BP when compared with ibuprofen and naproxen. Previous analyses from TARGET reported that treatment with lumiracoxib resulted in significantly smaller mean changes in diastolic and systolic BP compared with ibuprofen and naproxen over 52 weeks. 6 The analyses presented here have examined the effects of lumiracoxib, ibuprofen, and naproxen treatment on BP at 4 weeks (the first scheduled visit after start of study treatment) and at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months. These analyses confirmed previous findings that the use of NSAIDs (ibuprofen and naproxen combined) resulted in a significantly greater change in systolic and diastolic BP than lumiracoxib as early as week 4 of treatment. The LSM change from baseline for systolic BP was +0.5 mm Hg and +2.44 mm Hg for lumiracoxib and NSAIDs, respectively; corresponding values for diastolic BP were −0.02 mm Hg and +0.72 mm Hg, respectively. These differences may be of clinical significance. A recent meta‐analysis has indicated that lumiracoxib effects on BP were similar to placebo at total daily doses of 400 mg, 200 mg, and 100 mg. 11

Hypertension is present in half of patients by age 60 and increases in incidence at ages older than 60 years. Thus, many patients with OA are hypertensive or at risk of hypertension. A US National Center for Health Statistics survey reported that 40% of patients with OA have hypertension, compared with 25% in the general population without OA. 12 In these patients, there is a need for effective pain relief with minimal effect on BP. In addition, patients have different responses to therapies; a range of treatment options may be helpful. More than 45% of patients in TARGET were found to be hypertensive at baseline. Consequently, significantly less effect on BP may have clinical benefits over the long term for patients using lumiracoxib compared with NSAIDs. In the present analyses, the significantly larger changes in systolic and diastolic BP from baseline for ibuprofen compared with lumiracoxib correlated with a higher incidence of de novo (new‐onset) and aggravated hypertension (ie, a further increase in BP in hypertensive patients) in the ibuprofen patient group. The possible loss of BP control may also create a burden on physicians' time and an increase in drug costs related to the initiation and titration of anti‐hypertensive agents.

Both NSAIDs and selective COX‐2 inhibitors can increase BP compared with placebo. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 An association between the use of NSAIDs and elevated BP has been found in several meta‐analyses. 13 , 18 It is likely that these agents differ in their effects on BP. Indeed, rofecoxib has been reported to have a more pronounced effect on BP compared with NSAIDs. 16 In the recent Multinational Etoricoxib and Diclofenac Arthritis Long‐Term (MEDAL) study, discontinuations due to hypertension were observed more frequently with etoricoxib compared with diclofenac. In patients with treated hypertension, the class of antihypertensive medication used also appears to affect the impact that an NSAID or COX‐2 inhibitor might have on BP. 19 , 20 For example, indomethacin has been shown to increase BP more in patients treated with an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor (enalapril) than patients receiving a calcium channel blocker (amlodipine). 19 A 4‐week randomized ambulatory BP study noted that 24‐hour ambulatory systolic BP was 5 mm Hg higher with ibuprofen 600 mg 3 times daily compared with lumiracoxib 100 mg once daily in the overall population; this was more pronounced (8‐mm Hg difference) in patients receiving angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor monotherapy. 21

TARGET was not designed to elucidate the mechanistic aspects of any drug effects observed. It is therefore difficult to draw conclusions on the precise mechanism of the observed differences of the effects of lumiracoxib and the NSAIDs ibuprofen and naproxen on BP. It is possible that a difference in sodium retention with these agents is a contributory factor. Alternatively, the differing dose regimens and pharmacokinetics may play a role. Unlike other selective COX‐2 inhibitors, lumiracoxib distributes preferentially into inflamed tissue in vivo, a profile that may be attributed to its acidic nature. 22 , 23 In addition, in healthy persons, lumiracoxib demonstrates rapid absorption (median Tmax of 2 hours) and a short mean plasma half‐life (4 hours) 2 , 24 compared with other selective COX‐2 inhibitors. 25 The combination of lumiracoxib once‐daily dosing, rapid absorption, and a short mean plasma half‐life 24 , 25 may result in a reduced systemic exposure to lumiracoxib over the 24‐hour dosing period while still maintaining the preferential distribution into inflamed tissue, where it appears to have a longer duration of action. 23

Ibuprofen has a short plasma half‐life (2 hours) but it was administered 3 times daily, to its maximum daily dose (2400 mg), which could result in sustained systemic exposure over 24 hours. Similarly, naproxen has a longer half‐life (≈12 hours) and was given twice daily (500 mg each dose), which could also result in a sustained systemic exposure over 24 hours. The degree of pain may influence BP, and chronic pain intensity has been associated with an increase in clinical hypertension. 26 In TARGET there was no significant difference in the level of pain relief provided by lumiracoxib and NSAIDs. Therefore, a difference in analgesic efficacy is unlikely to account for the BP differences between lumiracoxib and NSAIDs observed in this analysis, but the once‐daily dosing might explain these observations.

Both COX‐1 and COX‐2 contribute to the regulation of several aspects of normal renal function. 3 , 4 Although a numerically greater proportion of patients had lower creatinine clearance values with lumiracoxib than with NSAIDs, this suggests a decrease in renal function but did not translate into treatment differences in the frequency of renal and urinary adverse events, including major renal adverse events. 8 Furthermore, the recommended dosage of lumiracoxib for treating OA pain (100 mg once daily) is lower than that used in TARGET (400 mg once daily). In clinical use, lumiracoxib may therefore be associated with an improved renal safety profile. Indeed, two 13‐week trials in knee OA patients have not reported any major renal adverse events with lumiracoxib 100 mg. 27 , 28

A limitation of this study was the lack of a formal definition of the thresholds of increase in BP required for the adverse events of de novo (new‐onset) hypertension and aggravated hypertension (further increased BP in hypertensive patients). Instead, the incidence of de novo and aggravated hypertension was obtained by investigator‐reported adverse events, and thus diagnosis is based on investigators' clinical practice. The size of the trial and the blinding of treatment allocation would nevertheless support the robustness of the results.

Data presented here support the hypothesis that there are differing BP profiles for lumiracoxib and NSAIDs. There remains a need for effective pain relief in patients with OA. The differential response of patients to treatments makes it useful to have a variety of treatment options. An understanding of the BP changes with different agents may assist in choosing the right treatment for the individual patient.

CONCLUSIONS

Lumiracoxib has a more favorable effect on BP following short‐ and long‐term treatment when compared with ibuprofen and naproxen. Furthermore, the renal safety of lumiracoxib appears to be comparable to that of ibuprofen and naproxen. Given the GI safety profile of lumiracoxib and the differing effects on BP noted in the present analyses, lumiracoxib may provide clinically important benefits over NSAIDs in patients with OA.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to thank the investigators and patients who participated in the original trial. The authors would also like to thank Rebecca Douglas from ACUMED for help with preparing this manuscript. The study, statistical analyses, and manuscript preparation were funded by the sponsor, Novartis Pharma AG. Michael Farkouh has received research grants from Glaxo‐Smith Kline, Merck, Roche and VIA Pharmaceuticals. He has two consultancy/advisory board relationships with Novartis, and has served as an advisor to CV Therapeutics and AstraZeneca. Freek Verheugt has a consultancy/advisory board relationship with Novartis (TARGET study and Cardiovascular Advisory Board). Sean Ruland has received research grants from Northstar Neuroscience Inc.;payment for speakers' bureau appointments from Genentech, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Vissol Inc.; and honoraria from various review courses and has a consultancy/advisory board relationship with Novartis. Howard Kirshner has received research grants for National Institutes of Health‐funded trials (SPS3, ALIAS, and MR Rescue) and industry‐funded trials (Boehringer Ingelheim PRoFESS and Bristol‐Myers Squibb/Sanofi MATCH) and payment for speakers' bureau appointments from Bristol‐Myers Squibb/Sanofi, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Janssen, and Novartis and has consultancy/advisory board relationships with AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Bristol‐Myers Squibb/Sanofi. Xavier Gitton, Gerhard Krammer, Kirstin Stricker, Peter Sallstig, and Bernd Mellein are employees of, and own stock options in, Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. Patrice Matchaba is an employee of, and owns stock options in, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, NJ. James Chesebro has received payment for STRIVE (an independent speakers' bureau funded by educational grants from Sanofi‐Aventis and Bristol‐Myers Squibb), and honoraria from multiple medical centers and has a consultancy/advisory board relationship with Novartis (TARGET study and Cardiovascular Advisory Board). Raban Jeger has nothing to disclose.

References

- 1. Woolf AD, Pfleger B. Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81(9):646–656. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jeger RV, Greenberg JD, Ramanathan K, et al. Lumiracoxib, a highly selective COX‐2 inhibitor. Expert Review Clin Immunol. 2005;1:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brater DC, Harris C, Redfern JS, et al. Renal effects of COX‐2‐selective inhibitors. Am J Nephrol. 2001;21:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harris RC. Cyclooxygenase‐2 and the kidney: functional and pathophysiological implications. J Hypertens (Suppl). 2002;20(suppl 6):S3–S9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Singh G, Miller JD, Huse DM, et al. Consequences of increased systolic blood pressure in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:714–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Farkouh ME, Kirshner H, Harrington RA, et al. TARGET Study Group . Comparison of lumiracoxib with naproxen and ibuprofen in the Therapeutic Arthritis Research and Gastrointestinal Event Trial (TARGET), cardiovascular outcomes: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:675–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hawkey CJ, Farkouh M, Gitton X, et al. Therapeutic Arthritis Research and Gastrointestinal Event Trial of lumiracoxib: study design and patient demographics. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schnitzer TJ, Burmester GR, Mysler E, et al. Comparison of lumiracoxib with naproxen and ibuprofen in the Therapeutic Arthritis Research and Gastrointestinal Event Trial (TARGET), reduction in ulcer complications: randomised controlled trial. TARGET Study Group . Lancet. 2004;364:665–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Publication No. 04–5230. National Institutes of Health ; 2004. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/hypertension/jnc7full.pdf. Accessed January 22, 2008.

- 10. Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. 2007 Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1462–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Whitehead A, Simmonds M, Mellein B, et al. Blood pressure profile of lumiracoxib is similar to placebo in arthritis patients [abstract P309]. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14(suppl 2):S168–S169. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Singh G, Miller JD, Lee FH, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors among US adults with self‐reported osteoarthritis: data from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Am J Manag Care. 2002;8:S383–S391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pope JE, Anderson JJ, Felson DT. A meta‐analysis of the effects of nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs on blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:477–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Whelton A, Fort JG, Puma JA, et al. SUCCESS VI Study Group . Cyclooxygenase‐2‐specific inhibitors and cardiorenal function: a randomized, controlled trial of celecoxib and rofecoxib in older hypertensive osteoarthritis patients. Am J Ther. 2001;8:85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schwartz JI, Vandormael K, Malice MP, et al. Comparison of rofecoxib, celecoxib, and naproxen on renal function in elderly subjects receiving a normal‐salt diet. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;72:50–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aw TJ, Haas SJ, Liew D, et al. Meta‐analysis of cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitors and their effects on blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:490–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Maillard M, Burnier M. Comparative cardiovascular safety of traditional nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2006;5:83–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Johnson AG, Nguyen TV, Day RO. Do nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs affect blood pressure? A meta‐analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:289–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Morgan TO, Anderson A, Bertram D. Effect of indomethacin on blood pressure in elderly people with essential hypertension well controlled on amlodipine and enalapril. Am J Hypertens. 2000;13:1161–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Whelton A, White WB, Bello AE, et al. SUCCESS‐VII Investigators . Effects of celecoxib and rofecoxib on blood pressure and edema in patients ≥65 years of age with systemic hypertension and osteoarthritis. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:959–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. MacDonald TM, Reginster J‐Y, Richard D, et al. Reduced destabilization of blood pressure with lumiracoxib compared to ibuprofen in osteoarthritis patients with controlled hypertension treated with ACE inhibitor monotherapy [abstract 265]. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15(suppl 3) :C149. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weaver ML, Flood DJ, Kimble EF, et al. Lumiracoxib demonstrates preferential distribution to inflamed tissue in the rat following a single oral dose: an effect not seen with other cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitors [abstract AB0044]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(suppl 1):378. 12634250 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Scott G, Rordorf C, Reynolds C, et al. Pharmacokinetics of lumiracoxib in plasma and synovial fluid. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43:467–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hartmann S, Scott G, Rordorf C, et al. Lumiracoxib demonstrates high absolute bioavailability in healthy subjects [abstract P‐99]. In: Tulunay FC, Orme M, eds. European Collaboration: Towards Drug Development and Rational Drug Therapy. Proceedings of the Sixth Congress of the European Association for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. Berlin, Germany: Springer‐Verlag; 2003:124. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brune K, Hinz B. Selective cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitors: similarities and differences. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004;33:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bruehl S, Chung OY, Jirjis JN, et al. Prevalence of clinical hypertension in patients with chronic pain compared to nonpain general medical patients. Clin J Pain. 2005;21:147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lehmann R, Brzosko M, Kopsa P, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of lumiracoxib 100 mg once daily in knee osteoarthritis: a 13‐week, randomized, double‐blind study vs. placebo and celecoxib. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:517–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sheldon E, Beaulieu A, Paster Z, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of lumiracoxib in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a 13‐week, randomized, double‐blind comparison with celecoxib and placebo. Clin Ther. 2005;27:64–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]