Abstract

Hypertension treatment guidelines recommend initiating 2‐drug therapy whenever blood pressure (BP) is ≥20 mm Hg systolic or ≥10 mm Hg diastolic above goal. This post hoc pooled analysis of 2 multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, active‐controlled forced‐titration studies in 1235 patients with moderate and severe hypertension examined how baseline BP levels relate to the need for combination therapy by comparing the antihypertensive efficacy and tolerability of once‐daily fixed‐dose irbesartan/hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) 300/25 mg compared with irbesartan 300‐mg or HCTZ 25‐mg monotherapies. In study 1, patients with severe hypertension (seated diastolic BP [SeDBP] ≥110 mm Hg) were treated for 7 weeks with irbesartan or irbesartan/HCTZ combination therapy, with forced‐titration after week 1. In study 2, patients with moderate hypertension (seated systolic BP [SeSBP] 160–180 mm Hg or SeDBP 100–110 mm Hg) were treated for 12 weeks with irbesartan/HCTZ, irbesartan monotherapy, or HCTZ monotherapy, with forced‐titration after week 2. The relationship between baseline BP and the likelihood of achieving BP goals (SeSBP <140 mm Hg or SeDBP <90 mm Hg; SeSBP <130 mm Hg or SeDBP <80 mm Hg) as well as the antihypertensive response was evaluated at week 7/8. The need for combination therapy increased with increasing baseline BP and lower BP goals across the range of BP levels studied, with a comparable adverse effect profile to monotherapy. These results suggest that the likelihood of achieving an early BP goal for a given BP severity should be considered when choosing initial combination therapy vs monotherapy.

Hypertension affects approximately one‐third of the adult population. 1 It is the most prevalent modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease and the most common risk factor for death from any cause worldwide. 2 , 3 Lowering blood pressure (BP) can produce rapid reductions in vascular disease risk in people with hypertension. 4 , 5 , 6 Current hypertension treatment guidelines recommend lowering BP to <140/90 mm Hg in the general population and to <130/80 mm Hg in persons with diabetes and renal disease. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 Recently, the European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology (ESH/ESC) 2007 guidelines 10 have broadened their lower BP (<130/80 mm Hg) target group to include patients with cerebrovascular disease and coronary heart disease. Similarly, the American Heart Association (AHA) Council for High Blood Pressure Research and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology and Epidemiology and Prevention 11 recommend a lower goal BP (<130/80 mm Hg) for patients with coronary artery disease, coronary artery disease risk equivalents, carotid artery disease (carotid bruit or abnormal findings on carotid ultrasound or angiography), peripheral arterial disease, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and a high cardiovascular risk (10‐year Framingham risk score >10%). Despite these guidelines, a significant percentage of patients are not being treated to BP goal. 2 , 12

Patients at high cardiovascular risk, such as patients with moderate and severe (≥160/100 mm Hg) hypertension, defined as stage 2 hypertension by the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) 7 and grade 2 or 3 hypertension by the 2007 ESH/ESC guidelines, 10 benefit from early and aggressive antihypertensive treatment to reduce their BP as quickly as possible. 5 , 6 Hypertension treatment guidelines recommend initiating treatment with 2‐drug therapy whenever BP is ≥20 mm Hg systolic or ≥10 mm Hg diastolic above the recommended goal. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 The most widely used drug combinations include an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor, or β‐blocker all with hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ), a thiazide diuretic. Recent clinical studies in moderate and severe hypertension show that a combination of the ARB irbesartan with HCTZ is safe and effective in patients irrespective of baseline BP level, age, obesity, race, diabetic status, and the metabolic syndrome 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 and has a significantly greater dose‐dependent BP‐lowering effect than either agent alone. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 Adequate dosages of irbesartan monotherapy, however, have also been associated with high BP control rates in hypertensive individuals, 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 which raises the question of which baseline BP level would warrant the need for irbesartan combination therapy vs monotherapy. The US Food and Drug Administration and the Cardiorenal Advisory Committee have recently suggested that physicians should be presented with efficacy data across a wide range of BP levels so that they can decide when to initiate treatment with combination therapy instead of monotherapy. This strategy represents a new and important approach to the labeling of antihypertensive drugs.

The following post hoc analysis was designed to examine how baseline BP levels relate to the need for combination therapy compared with monotherapy. In this study, the treatment effects and tolerability of irbesartan monotherapy were compared with those of an irbesartan/HCTZ fixed‐dose combination therapy across a range of baseline BP levels spanning moderate to severe hypertension.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a pooled post hoc analysis of 2 multi‐center, randomized, double‐blind, active‐controlled forced‐titration studies assessing the antihypertensive efficacy and tolerability of once‐daily fixed‐dose irbesartan/HCTZ 300/25 mg vs irbesartan 300‐mg monotherapy in patients with moderate or severe hypertension (BP ≥20 mm Hg above the JNC 7‐recommended systolic BP [SBP]/diastolic BP [DBP] goals 7 ). Full details of the individual studies have previously been published. 29 , 30 Briefly:

-

•

Study 1 was a 7‐week trial in patients with severe hypertension (seated DBP [SeDBP] ≥110 mm Hg), conducted at 250 study centers in North America, Europe, and Asia. Eligible patients entered a 7‐day single‐blind placebo lead‐in period. Patients with SeDBP ≥110 mm Hg at 2 consecutive visits during the lead‐in period were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to irbesartan/HCTZ 150/12.5‐mg fixed‐dose combination therapy force‐titrated to 300/25 mg after week 1 or irbesartan 150‐mg monotherapy force‐titrated to 300 mg after week 1.

-

•

Study 2 was a 12‐week trial in patients with moderate hypertension (seated SBP [SeSBP] 160–180 mm Hg or SeDBP 100–110 mm Hg), conducted at 150 study centers in North America, Europe, and Asia. Eligible patients entered a 21‐day single‐blind placebo wash‐out period before randomization in a 3:1:1 ratio to irbesartan/HCTZ 150/12.5‐mg fixed‐dose combination therapy force‐titrated to 300/25 mg after week 2, irbesartan 150‐mg monotherapy force‐titrated to 300 mg after week 2, or HCTZ 12.5‐mg monotherapy force‐titrated to 25 mg after week 2.

Patients were not eligible for either of the 2 studies if they had SeSBP ≥220 mm Hg, SeDBP ≥130 mm Hg, known or suspected secondary hypertension, or any condition that required more immediate BP lowering. In both studies, all patients gave a detailed medical history and underwent a complete physical examination at study entry, including 12‐lead electrocardiography. During active treatment, average seated BP was measured, followed by standing trough BP (24±3 hours postdose) and heart rate. All study medication was taken once daily between 6 am and 11 am, except on the morning of a study visit.

Baseline demographics (other than baseline BP level) and the absolute amount by which SBP was lowered were similar in the 2 studies, hence justifying pooling patient data in a post hoc analysis. Together, the patient populations spanned the range of stage 2 (JNC 7 guidelines 7 ) and grade 2 or 3 hypertension (ESH/ESC 2007 guidelines 10 ).

A post hoc pooled analysis of studies 1 and 2 was carried out to examine the relationship between baseline BP level and the likelihood of achieving BP goals (SeSBP <140 mm Hg or SeDBP <90 mm Hg; SeSBP <130 mm Hg or SeDBP <80 mm Hg) with irbesartan/HCTZ combination therapy compared with irbesartan monotherapy and HCTZ monotherapy at week 7/8 using a logistic regression model. The relationship between baseline BP level and the magnitude of antihypertensive response, together with the tolerability of combination therapy vs irbesartan monotherapy and HCTZ monotherapy, was also evaluated.

Statistics

In both studies, efficacy evaluations were conducted on the intent‐to‐treat population, and safety evaluations were conducted on all randomized patients who took at least 1 dose of double‐blind study medication. Patients who had a missing postbaseline SeSBP (or SeDBP) reading at week 7/8 were defined as not meeting their SeSBP (or SeDBP) target. Logistic regression curves were generated for each study using a model of separate slopes between treatment arms to assess the relationship between baseline BP and the probability of achieving the following goals:

-

•

<140 mm Hg SeSBP vs baseline SeSBP

-

•

<130 mm Hg SeSBP vs baseline SeSBP

-

•

<90 mm Hg SeDBP vs baseline SeDBP

-

•

<80 mm Hg SeDBP vs baseline SeDBP

In addition to the analyses by study and treatment arm, data from the 2 studies were combined at the individual patient level. BP changes from baseline and the probability of achieving goal BP were assessed. Patients with a baseline SeSBP of 140 to <220 mm Hg were used for the SeSBP analyses, and patients with a baseline SeDBP of 90 to <130 mm Hg were used for SeDBP analyses. These ranges were selected based on patients whose BP level was above target at baseline and within protocol‐specified limits for the upper range of BP. Logistic regression curves were generated for the combined studies using either a common slope model or a separate slope model to assess the relationship between baseline BP and the probability of achieving these goals. The determination of the common/separate slope models was carried out using differences in model likelihood (chi‐squared test with 2 df).

RESULTS

Among the 1235 patients enrolled in the 2 studies, 796 were randomized to receive irbesartan/HCTZ combination therapy, 335 to irbesartan monotherapy, and 104 (all with moderate hypertension) to HCTZ monotherapy. Of these, 1093 patients (88%) completed the study: 707 participants in the combination therapy group, 295 in the irbesartan monotherapy group, and 91 in the HCTZ monotherapy group. The most common reasons for study discontinuation were unresponsiveness to therapy and adverse events (AEs).

Patient characteristics were similar in each of the pooled treatment groups (Table I). Most patients were middle‐aged (mean age, 54 years); approximately one‐half (56%) were men, and 84% were white. At baseline, the mean diastolic and systolic BP levels were 106.95 mm Hg and 167.28 mm Hg, respectively. Overall, 464 patients (37.6%) had hyperlipidemia, while 156 (12.6%) had diabetes mellitus. In total, 52.0%, 56.7%, and 45.2% of patients in the irbesartan/HCTZ, irbesartan, and HCTZ groups, respectively, had previously received antihypertensive therapy.

Table I.

Baseline Characteristics for the Pooled Analysis Safety Population

| Irbesartan/HCTZ (n=796) | Irbesartan (n=335) | HCTZa (n=104) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (range), y | 53.4 (23–87) | 53.7 (25–87) | 56.0 (21–83) |

| Male sex, % | 57.6 | 51.6 | 59.6 |

| White race, % | 83.7 | 85.6 | 82.7 |

| Black race, % | 14.7 | 12.8 | 14.4 |

| Weight (range), kg | 88.8 (46.0–164.3) | 90.7 (44.0–151.5) | 88.4 (55.0–146.1) |

| Baseline DBP (range), mm Hg | 106.8 (66.0–131.6) | 108.4 (74.3–135.0) | 97.6 (74.7–110.7) |

| Baseline SBP (range), mm Hg | 167.5 (127.7–221.7) | 168.4 (135.7–220.7) | 162.0 (136.0–180.0) |

| Baseline heart rate (range), bpm | 76.6 (48.0–111.0) | 76.2 (52.0–117.0) | 76.6 (50.0–108.0) |

| Medical history, % | |||

| Diabetes | 12.4 | 13.1 | 12.5 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 38.2 | 36.7 | 35.6 |

| Stable angina pectoris | 2.3 | 4.2 | 1.0 |

| Stroke or transient ischemic attack | 1.5 | 2.1 | 1.0 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.9 |

| Previous antihypertensive therapy | 52.0 | 56.7 | 45.2 |

| aStudy 2 (patients with moderate blood pressure) only. Abbreviations: bpm, beats per minute; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HCTZ, hydrochlorothiazide; SBP, systolic blood pressure. | |||

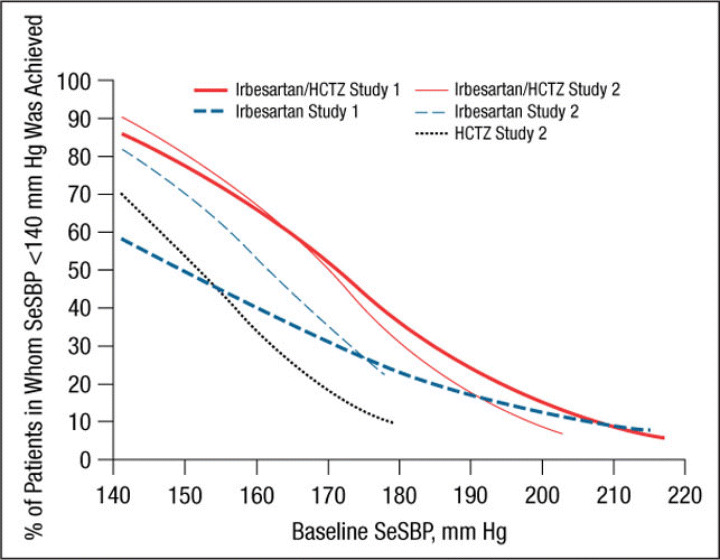

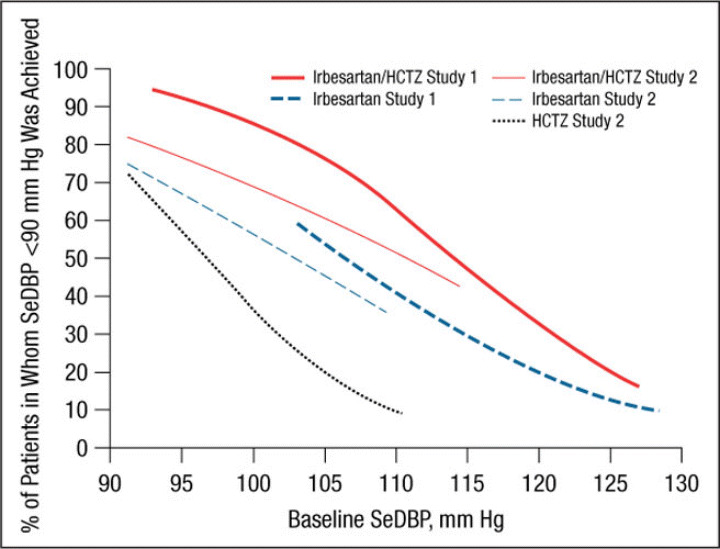

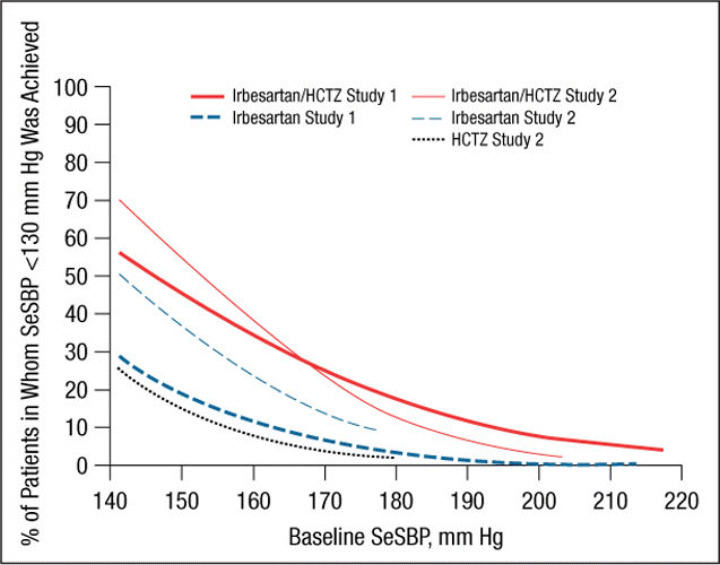

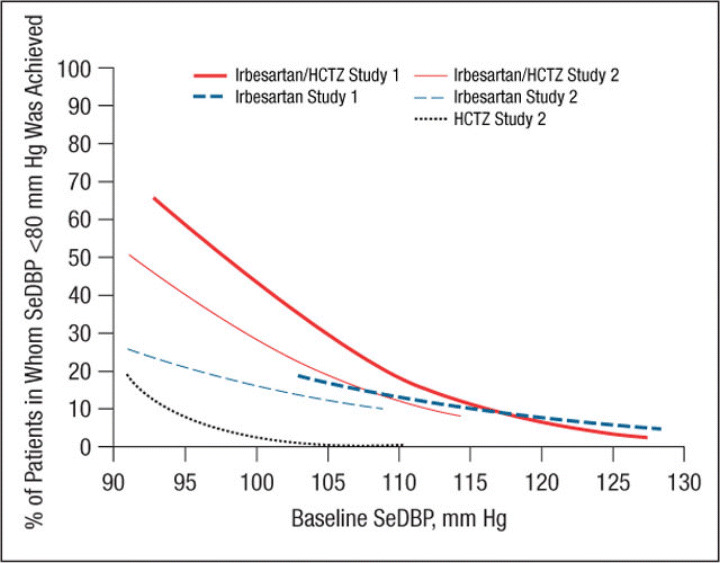

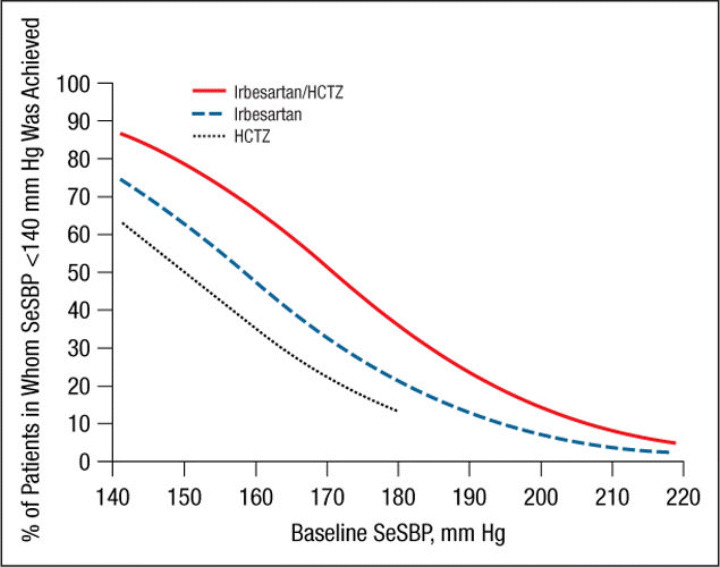

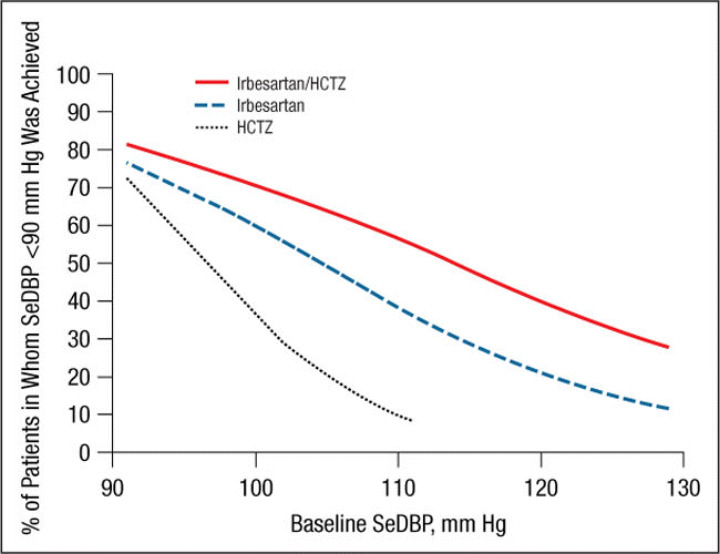

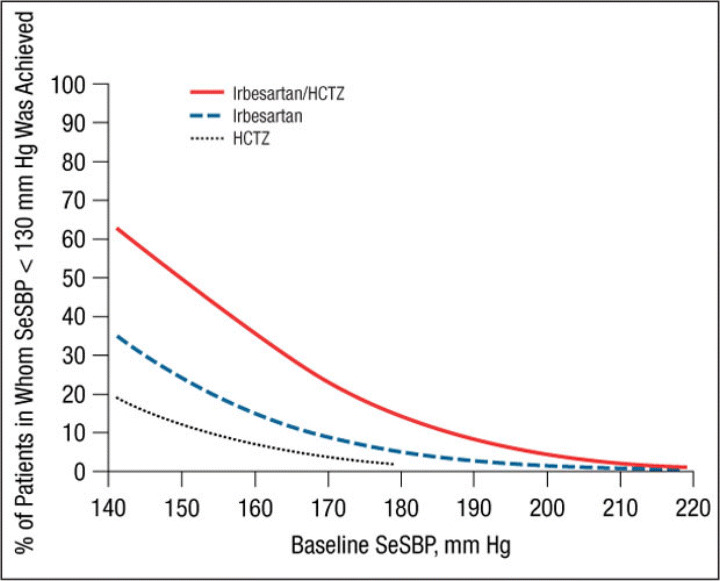

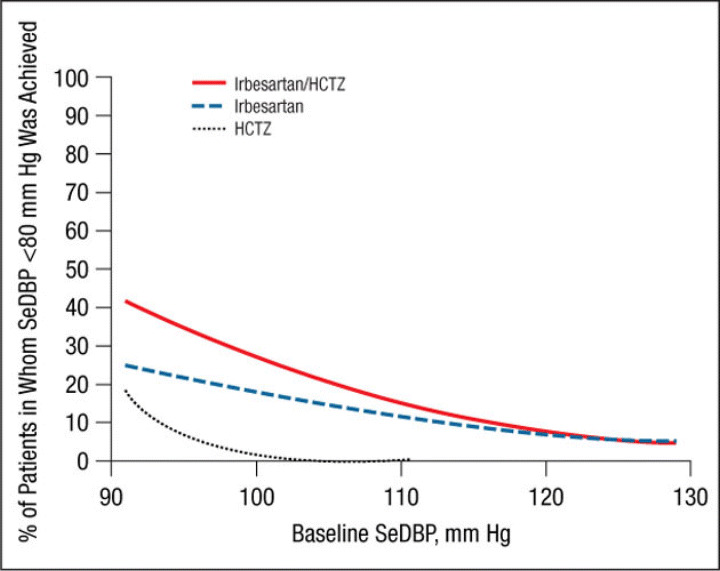

The mean ± SE treatment‐related changes from baseline to week 7/8 in SeDBP and SeSBP and the mean changes in SeSBP, according to baseline BP strata, are given in Table II. Results of the logistic regression model by study are presented in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, and Figure 4. These graphs have been incorporated into the irbesartan/HCTZ US product label. A total of 1195 patients had baseline SeSBP values from 140 to <220 mm Hg, and 1141 had baseline SeDBP values from 90 to <130 mm Hg. In terms of the model selection for the pooled analyses, the common slope model was supported for SeSBP (P=.25 for target SeSBP <140 mm Hg; P=.49 for target SeSBP <130 mm Hg), while the separate slope model was used for SeDBP (P=.02 for target SeDBP <90 mm Hg; P=.11 for target SeDBP <80 mm Hg). The resulting logistic regression curves are shown in Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, and Figure 8.

Table II.

Mean Changes from Baseline to Study End in SeSBP by Baseline SeSBP Strata (Primary Analysis Population)

| Irbesartan/HCTZ | Irbesartan | HCTZ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Mean Change (SE), mm Hg | No. | Mean Change (SE), mm Hg | No. | Mean Change (SE), mm Hg | |

| Baseline SeSBP, mm Hg | ||||||

| 140–159 | 180 | −22.1 (0.91) | 74 | −14.3 (1.41) | ||

| 160–179 | 406 | −30.4 (0.69) | 161 | −23.2 (1.16) | ||

| >180 | 120 | −42.9 (1.68) | 56 | −30.6 (2.70) | ||

| Overall | 706 | −29.9 (0.59) | 291 | −21.7 (0.97) | 104 | −15.7 (1.53) |

| Baseline SeDBP, mm Hg | ||||||

| −Overall | 706 | −20.4 (0.38) | 291 | −17.3 (0.63) | 104 | −7.2 (0.75) |

| Abbreviations: HCTZ, hydrochlorothiazide; SeSBP, seated systolic blood pressure. | ||||||

Figure 1.

Probability of achieving a seated systolic blood pressure (SeSBP) <140 mm Hg at weeks 7 (study 1) and 8 (study 2). In this probability curve, patients without blood pressure measurements at week 7/8 were counted as not reaching goal. HCTZ indicates hydrochlorothiazide.

Figure 2.

Probability of achieving a seated diastolic blood pressure (SeDBP) <90 mm Hg at weeks 7 (study 1) and 8 (study 2). HCTZ indicates hydrochlorothiazide.

Figure 3.

Probability of achieving a seated systolic blood pressure (SeSBP) <130 mm Hg at weeks 7 (study 1) and 8 (study 2). HCTZ indicates hydrochlorothiazide.

Figure 4.

Probability of achieving a seated diastolic blood pressure (SeDBP) <80 mm Hg at weeks 7 (study 1) and 8 (study 2). HCTZ indicates hydrochlorothiazide.

Figure 5.

Probability of achieving a seated systolic blood pressure (SeSBP) <140 mm Hg at week 7/8. In this probability curve, patients without blood pressure measurements at week 7/8 were counted as not reaching goal. HCTZ indicates hydrochlorothiazide.

Figure 6.

Probability of achieving a seated diastolic blood pressure (SeDBP) <90 mm Hg at week 7/8. HCTZ indicates hydrochlorothiazide.

Figure 7.

Probability of achieving a seated systolic blood pressure (SeSBP) <130 mm Hg at week 7/8. HCTZ indicates hydrochlorothiazide.

Figure 8.

Probability of achieving a seated diastolic blood pressure (SeDBP) <80 mm Hg at week 7/8. HCTZ indicates hydrochlorothiazide.

Irbesartan/HCTZ was generally associated with a greater likelihood of achieving an SeSBP <140 mm Hg (Figure 1 and Figure 5) or SeDBP <90 mm Hg (Figure 2 and Figure 6) relative to irbesartan or HCTZ monotherapies across the range of BP levels studied. In the separate slope models by study, the difference between the irbesartan/HCTZ and irbesartan arms in the likelihood of achieving a BP target tended to be smaller in patients with very high baseline BP levels (Figure 1 and Figure 2). In all cases, the likelihood of achieving BP goals increased as baseline BP decreased for all groups. For example, the probability of achieving a post‐treatment value of <140 mm Hg for a patient with a baseline SeSBP of 185 mm Hg is approximately 30% with irbesartan/HCTZ and 16% with irbesartan monotherapy (Figure 5). For patients with a baseline SeSBP of 160 mm Hg, the respective probabilities are 66% and 48% and only 35% for patients receiving HCTZ monotherapy.

Similar results were obtained for a variety of target goals, including SeSBP <130 mm Hg (Figure 3 and Figure 7) or SeDBP <80 mm Hg (Figure 4 and Figure 8), although the proportions of patients in whom target BP was reached decreased as the goal BP was lowered. For example, among patients with a baseline SeSBP of 160 mm Hg, a goal BP <130 mm Hg was achieved in only 35% of those treated with combination therapy, 17% of those treated with irbesartan monotherapy, and 8% of those treated with HCTZ monotherapy (Figure 7). Although combination therapy remained insufficient for the majority of patients with severely elevated baseline BP and/or lower BP goals, substantially greater BP reductions were achieved with combination therapy than with irbesartan monotherapy across all baseline SeSBP levels (Table II). This suggests that adding a third agent to combination therapy would be more effective for achieving BP goals than adding a second agent to monotherapy.

The types and rates of AEs experienced by patients treated with irbesartan/HCTZ were comparable to those reported by patients treated with irbesartan or HCTZ monotherapy (Table III). Overall, AEs were experienced by 37% of patients treated with combination therapy, 39% of those treated with irbesartan monotherapy, and 39.4% of those treated with HCTZ monotherapy. Treatment‐related AEs were reported by 12.5%, 10.5%, and 7.7% of patients in each of the respective treatment groups. Only 0.9%, 0.3%, and 2.9% of patients, respectively, experienced serious AEs, and there were no deaths in any of the treatment groups.

Table III.

AEs Associated With Irbesartan/HCTZ Combination Therapy, Irbesartan Monotherapy, and HCTZ Monotherapy

| %of Patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Irbesartan/HCTZ (n=796) | Irbesartan (n=333)a | HCTZ (n=104) | |

| Total AEs | 37.0 | 39.0 | 39.4 |

| Treatment‐related AEs | 12.5 | 10.5 | 7.7 |

| Treatment discontinuations due to AEs | 3.5 | 2.7 | 4.8 |

| Serious AEs | 0.9 | 0.3 | 2.9 |

| Deaths | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AEs of special interest | 9.6 | 9.9 | 6.7 |

| Dizziness | 3.4 | 1.5 | 1.0 |

| Headache | 4.8 | 5.7 | 4.8 |

| Hyperkalemia | 0.6 | 0 | 1.0 |

| Hypokalemia | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0 |

| Hypotension | 0.7 | 0 | 0 |

| Syncope | 0 | 0 | 1.0 |

| aTwo patients discontinued the study before receiving therapy. Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; HCTZ, hydrochlorothiazide. | |||

DISCUSSION

In this pooled analysis of 2 randomized, double‐blind active‐controlled trials, irbesartan/HCTZ combination therapy was associated with a greater degree of BP‐lowering and a greater likelihood of achieving goal BP after 7/8 weeks than was irbesartan or HCTZ monotherapy, across the range of BP levels studied. These results are consistent with those from previous studies in which irbesartan/HCTZ combination therapy effectively lowered BP to goal in patients with difficult‐to‐treat hypertension. 14 , 19 , 23 , 29 , 30

Our study suggests that although a goal BP of <140/90 mm Hg can be reached in the majority of patients with SBP <160 mm Hg with irbesartan monotherapy, most patients with moderate to severe (stage 2 7 or grade 2 or 3 10 ) hypertension (baseline SBP ≥160 mm Hg) require combination therapy for BP goal to be reached (Figure 1, Figure 3, Figure 5, and Figure 7). This observation is consistent with the current hypertension treatment guidelines that state that the majority of patients with hypertension require at least 2 drugs with different mechanisms of action for BP control to be attained and that the treatment of stage 2 hypertension should be initiated with combination therapy. 4 , 7 , 8 , 10 , 11 Our study also shows that although combination therapy is effective in patients with stage 2 hypertension (in the pooled analysis, the mean reduction in SeSBP in patients with baseline SBP ≥180 mm Hg was 43 mm Hg [Table III]), baseline BP is so far above goal in many of these patients that a third or even a fourth antihypertensive agent may be required to achieve effective BP control.

In addition to a greater need for combination therapy in patients with higher baseline BP levels, more aggressive therapy is also required in patients with lower BP goals. In the pooled analysis, the proportions of patients with a baseline SBP of 160 mm Hg in whom a goal BP <140 mm Hg was achieved with combination therapy, irbesartan monotherapy, and HCTZ monotherapy were 66%, 48%, and 35%, respectively (Figure 5) compared with 35%, 17%, and 8% of those in whom a goal BP <130 mm Hg was reached (Figure 7). Given that the 2007 ESH/ESC 10 and AHA hypertension treatment guidelines 11 recommend reducing BP to the lower goal of <130/80 mm Hg in a wider patient group than previously suggested, more patients than ever are likely to require combination therapy rather than monotherapy.

Previous studies have shown that the individual components of combination therapies can be given in a low‐dose range that is more likely to be free of adverse effects than the higher doses of monotherapies that might be required to achieve the same BP goal. 31 Furthermore, some antihypertensive agents have the potential to attenuate the AEs caused by other drugs. For example, diuretic‐induced alterations in potassium, serum cholesterol, and fasting glucose values can be offset by the concomitant administration of an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or an ARB. 16 The types and incidences of AEs reported in this study by patients treated with irbesartan/HCTZ were comparable to the AE profile for patients treated with irbesartan or HCTZ monotherapy. Moreover, combination therapy reduced the risk of headache compared with irbesartan monotherapy and did not result in an increased incidence of hypotension, syncope, or dizziness—effects that might be expected to occur if BP is reduced too quickly.

Given the results of this analysis, it would be appropriate to initiate antihypertensive treatment in patients with stage 2 hypertension using ARB/HCTZ combination therapy, to titrate to the maximum dose, if required, and to add a third medication within weeks if BP control is still not achieved. Antihypertensive treatment strategies, however, should be selected according to the needs of each individual patient. In addition to hypertension, some patients may have additional cardiovascular risk factors, such as diabetes, which suggest a greater urgency for quicker BP control. These patients may benefit from first‐step combination therapy even if their BP level is in a range that might be effectively reduced using monotherapy. Other patients may have special safety concerns, such as risk factors for hypotension, and may benefit from initial monotherapy even if their BP level is relatively high. Thus, while the initial level of hypertension and goal BP are important considerations when deciding whether to initiate treatment using combination therapy or monotherapy, additional risk factors must also be considered.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of this post hoc pooled analysis are consistent with those of previous studies in which first‐step treatment using irbesartan/HCTZ combination therapy was well tolerated and more effective than irbesartan or HCTZ monotherapy in lowering BP to goal level in patients with a wide range of BP levels spanning moderate to severe (stage 2 7 or grade 2 or 3 10 ) hypertension. 14 , 23 , 30 , 32 Our finding that the need for combination therapy increases with increasing baseline BP supports the current hypertension treatment guidelines, which recommend initiating treatment using combination therapy in patients with moderate to severe hypertension and using monotherapy in those whose BP level is closer to goal. 7 , 10

Disclosures:

Dr Franklin is a member of the Speakers' Bureaus for Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, and Merck and is a consultant for AtCor Medical and Bristol‐Myers Squibb. Drs Lapuerta, Cox, and Donovan conducted this work as employees of Bristol‐Myers Squibb.

References

- 1. Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988–2000. JAMA. 2003;290(2):199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rosamond W, Flegal K, Friday G, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2007 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2007;115(5):e69–e171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thom T, Haase N, Rosamond W, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2006 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2006;113(6):e85–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Major outcomes in high‐risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288(23):2981–2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dahlof B, Sever PS, Poulter NR, et al. Prevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol adding bendroflumethiazide as required, in the Anglo‐Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial‐Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT‐BPLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9489):895–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, Weber M, et al. Outcomes in hypertensive patients at high cardiovascular risk treated with regimens based on valsartan or amlodipine: the VALUE randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9426):2022–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Douglas JG. Clinical guidelines for the treatment of hypertension in African Americans. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2005;5(1):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bakris GL, Williams M, Dworkin L, et al. Preserving renal function in adults with hypertension and diabetes: a consensus approach. National Kidney Foundation Hypertension and Diabetes Executive Committees Working Group . Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36(3):646–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension: The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2007;25(6):1105–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rosendorff C, Black HR, Cannon CP, et al. Treatment of hypertension in the prevention and management of ischemic heart disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology and Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2007;115(21):2761–2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ong KL, Cheung BMY, Man YB, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among United States adults 1999–2004. Hypertension. 2007;49(1):69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rosenstock J, Rossi L, Lin CS, et al. The effects of irbesartan added to hydrochlorothiazide for the treatment of hypertension in patients non‐responsive to hydrochlorothiazide alone. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1998;23(6):433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Neutel JM, Franklin SS, Oparil S, et al. Efficacy and safety of irbesartan/HCTZ combination therapy as initial treatment for rapid control of severe hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2006;8(12):850–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Franklin S, Lapuerta P. Early reduction of exposure to severe blood pressure levels with irbesartan/HCTZ as first‐line treatment of severe hypertension. Presented at: 16th Meeting of the European Society of Hypertension; June 1216, 2006; Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kochar M, Guthrie R, Triscari J, et al. Matrix study of irbesartan with hydrochlorothiazide in mild‐to‐moderate hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 1999;12(8, pt 1):797–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Howe P, Phillips P, Saini R, et al. The antihypertensive efficacy of the combination of irbesartan and hydrochlorothiazide assessed by 24‐hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Irbesartan Multicenter Study Group . Clin Exp Hypertens. 1999;21(8):1373–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Raskin P, Guthrie R, Flack J, et al. The long‐term antihypertensive activity and tolerability of irbesartan with hydrochlorothiazide. J Hum Hypertens. 1999;13(10):683–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Coca A, Calvo C, Sobrino J, et al. Once‐daily fixed‐combination irbesartan 300 mg/hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg and circadian blood pressure profile in patients with essential hypertension. Clin Ther. 2003;25(11):2849–2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Neutel JM, Saunders E, Bakris GL, et al. The efficacy and safety of low‐ and high‐dose fixed combinations of irbesartan/hydrochlorothiazide in patients with uncontrolled systolic blood pressure on monotherapy: the INCLUSIVE trial. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2005;7(10):578–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sowers JR, Neutel JM, Saunders E, et al. Antihypertensive efficacy of Irbesartan/HCTZ in men and women with the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2006;8(7):470–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ofili E, Nesbitt S, Bhaumik A, et al. Initial therapy with irbesartan/hydrochlorothiazide in black patients with severe hypertension. Presented at: National Medical Association 2007 Annual Convention and Scientific Assembly; August 49, 2007; Honolulu, HI. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lapuerta P. Irbesartan/HCTZ as initial treatment in patients with moderate hypertension. Presented at: 16th Meeting of the European Society of Hypertension; June 1216, 2006; Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Neutel JM, Bhaumik A, Ptaszynska A, et al. Efficacy and safety of irbesartan/hydrochlorothiazide as initial therapy in subgroups of patients with moderate to severe hypertension at high cardiovascular risk. Presented at: 17th Scientific Meeting of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH), June 1519, 2007; Milan, Italy. Abstract 242. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Coca A, Calvo C, Garcia‐Puig J, et al. A multicenter, randomized, double‐blind comparison of the efficacy and safety of irbesartan and enalapril in adults with mild to moderate essential hypertension, as assessed by ambulatory blood pressure monitoring: the MAPAVEL Study (Monitorizacion Ambulatoria Presion Arterial APROVEL). Clin Ther. 2002;24(1):126–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Littlejohn T II, Saini R, Kassler‐Taub K, et al. Long‐term safety and antihypertensive efficacy of irbesartan: pooled results of five open‐label studies. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1999;21(8):1273–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reeves RA, Lin CS, Kassler‐Taub K, et al. Dose‐related efficacy of irbesartan for hypertension: an integrated analysis. Hypertension. 1998;31(6):1311–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mimran A, Ruilope L, Kerwin L, et al. A randomised, double‐blind comparison of the angiotensin II receptor antagonist, irbesartan, with the full dose range of enalapril for the treatment of mild‐to‐moderate hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 1998;12(3):203–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Neutel J. Irbesartan/HCTZ combination therapy as initial treatment for severe hypertension to achieve rapid BP control. Presented at: 16th meeting of the European Society of Hypertension; June 1216, 2006; Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Neutel JM, Franklin SS, Lapuerta P, et al. A comparison of the efficacy and safety of irbesartan/HCTZ combination therapy with irbesartan and HCTZ monotherapy in the treatment of moderate hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2007 Oct 11;[Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Law MR, Wald NJ, Morris JK, et al. Value of low dose combination treatment with blood pressure lowering drugs: analysis of 354 randomised trials. BMJ. 2003;326(7404):1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Weir M, Neutel J, Bhaumik A, et al. Irbesartan/hydrochlorothiazide fixed‐dose combination is effective and well tolerated in moderate to severe (Stage 2) hypertensive patients with and without advanced age, obesity, and/or type 2 diabetes. Presented at: 22nd Meeting of the American Society of Hypertension; May 1922, 2007; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]