Abstract

In a large number of patients with hypertension, ≥2 antihypertensive agents are required to achieve blood pressure (BP) goals. There is good rationale for initial combination therapy based on clinical trials demonstrating that achievement of BP goals within a reasonably short period of time results in fewer cardiovascular events. One approach to attaining BP goals and improving medication adherence is fixed‐dose combination therapy, the use of which dates back to the 1960s. Given some of the advantages of renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system (RAAS) blockers in patients with heart disease, kidney disease, and diabetes, many combinations include either an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker. In most studies, however, thiazide diuretics were necessary to achieve goal BP. Calcium channel blockers have also been used in combination with angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors to lower BP. Studies are now under way to determine the relative benefits of an RAAS blocker/diuretic compared with an RAAS blocker/calcium channel blocker as initial therapy.

The global prevalence of hypertension in 2000 was 972 million, and it is predicted to rise to more than 1.5 billion by 2025. 1 Hypertension, a leading treatable risk factor for cardiovascular (CV) disease, has a significant health, economic, and societal impact. 2 Although it is well established that blood pressure (BP) lowering with antihypertensive therapy, even to less than goal levels, reduces the risk of CV disease, BP targets are not reached in many patients. Results might be better if goals were achieved. It is now widely accepted in that many patients, especially those with evidence of renal disease or diabetes, ≥2 antihypertensive drugs targeting different physiologic mechanisms of BP regulation are required to achieve BP goal.

There is good rationale for fixed‐dose combination (FDC) therapies; this has been the subject of previous reviews. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 The primary rationale for using FDCs is enhanced adherence to medication regimens compared with treatment given as 2 separate agents. 7 FDCs also facilitate more prompt reduction of BP. 8 , 9 Since the use of antihypertensive combinations started in the 1960s with hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) combined with the potassium‐sparing diuretic triamterene, newer and different combinations have been introduced. Thiazide diuretics and calcium channel blockers (CCBs) are effective, as well as combinations that include renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system (RAAS) blockers, in reducing BP. Several combinations of an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) with a diuretic or an ACEI with a CCB are available (Table). More recently, a combination of an ARB and a CCB (amlodipine/valsartan) has been introduced. This review evaluates the latest developments in the use of FDCs based on ARBs and ACEIs.

Table.

RAAS Blockers and Fixed‐Dose RAAS Blocker Combination Therapies

| RAAS Blockers | ||

|---|---|---|

| ACEIs | ARBs | |

| Single‐agent formulations | Benazepril, captopril, enalapril, lisinopril, quinapril, moexipril, delapril, fosinopril, perindopril, cilazapril, ramipril, trandolapril | Valsartan, losartan, irbesartan, eprosartan, telmisartan, candesartan, olmesartan |

| Combination with diuretics | Benazapril/HCTZ, captopril/HCTZ, enalapril/HCTZ, lisinopril/HCTZ, quinapril/HCTZ, moexipril/HCTZ, delapril/indapamide, fosinopril/HCTZ, perindopril/indapamide, cilazapril/HCTZ, ramipril/HCTZ | Valsartan/HCTZ, losartan/HCTZ, irbesartan/HCTZ, eprosartan/HCTZ, telmisartan/HCTZ, candesartan/HCTZ, olmesartan/HCTZ |

| Combination with CCBs | Benazepril/amlodipine, enalapril/felodipine, trandolapril/verapamil, ramipril/felodipine | Amlodipine/valsartan, olmesartan/amlodipinea |

| aUnder evaluation. Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; HCTZ, hydrochlorothiazide; RAAS, renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system. | ||

RAAS BLOCKADE

The RAAS regulates sodium balance, fluid volume, and BP. 10 Angiotensin II, the main effector peptide of the RAAS, binds to the angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptor and mediates a range of processes, including vasoconstriction, aldosterone and vasopressin release, sodium and water retention, and sympathetic activation, which can, in turn, lead to the development of hypertension. 10 ACEIs decrease levels of circulating angiotensin II by inhibiting angiotensin‐converting enzymes and thereby reducing the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II. ARBs, however, act by selectively blocking the binding of angiotensin to the AT1 receptor in the peripheral vasculature.

During the last 10 years, RAAS blockade with ACEIs or ARBs has become established as an effective option in the management of hypertension. The efficacy and safety of these antihypertensive therapies have been reviewed in detail elsewhere. 10 , 11 , 12

COMBINATION THERAPY WITH RAAS BLOCKERS

The mechanistic rationale for use of a diuretic with an RAAS blocker is that diuretic‐induced vasodilation reduces BP by inducing mild sodium depletion and reducing plasma volume. Consequently, diuretics may indirectly stimulate the RAAS, which may attenuate their efficacy. In most cases, however, this does not negate the BP‐lowering effects of these agents. A logical step is to combine an RAAS blocker (an ACEI or an ARB) with a diuretic to potentiate reductions in arterial pressure. 5 The pharmacologic rationale for the use of a CCB with an RAAS blocker is based on the buffering by the RAAS blocker of CCB‐induced activation of the sympathetic nervous system 13 and the RAAS, 4 as well as reinforcement of the antihypertensive effect of the RAAS blocker by the negative sodium balance caused by CCBs. 14 Dose‐dependent CCB‐induced peripheral edema may be minimized in the presence of an RAAS blocker. 5

ACEIs Plus Diuretics or CCBs

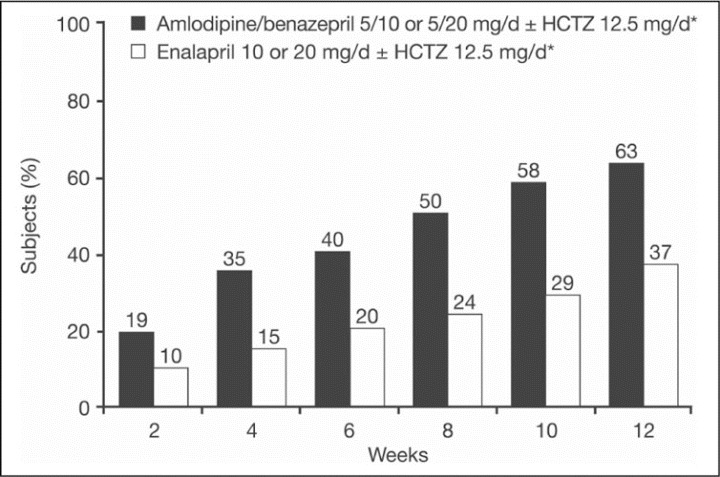

Combinations of ACEIs and a diuretic or a CCB have been used for many years and have been reviewed in detail. 3 , 4 , 5 Most of the long‐term clinical trials have used an RAAS blocker/diuretic combination. ACEI/CCB combinations have been shown to be effective in reducing BP in hypertensive patients with non‐insulin‐dependent diabetes and renal insufficiency without compromising remaining renal function. 15 Results of the Study of Hypertension and the Efficacy of Lotrel in Diabetics (SHIELD) suggested that initial therapy with an ACEI/CCB combination of benazepril/amlodipine may be more effective than enalapril monotherapy in achieving BP goals in a more timely fashion in patients with type 2 diabetes (Figure 1). 9 This combination and many other combinations would be expected to be more effective than monotherapy.

Figure 1.

Percentage of all participants in whom target blood pressure (BP) (<130/85 mm Hg) was achieved by week and treatment group (intent‐to‐treat population). *If the maximum dosage regimens did not reduce BP to target level, hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) 12.5 mg/d was added at week 8 (so that weeks 10 and 12 reflect diuretic add‐on therapy). Reproduced from Bakris and Weir 9 with permission from Blackwell Publishing.

The efficacy of benazepril/amlodipine 10 mg/5 mg has been compared with that of the ACEI/thiazide captopril/HCTZ (50/25 mg) in patients with mild to moderate hypertension. 16 Sitting diastolic BP (DBP) and systolic BP (SBP) levels at the end of active treatment were 2.7 and 3.7 mm Hg lower, respectively, with benazepril/amlodipine than with captopril/HCTZ (P<.001), and the response rate (defined as the proportion of patients with either a final sitting DBP value <90 mm Hg or decreased by ≥10 mm Hg or a sitting SBP value <150 mm Hg or decreased by ≥20 mm Hg from baseline) was significantly higher in the benazepril/amlodipine group than in the captopril/HCTZ group (94.8% vs 86.0%; P=.004). 16

Like the ACEI/thiazide combination, an ACEI/CCB has also been shown to be effective in reducing proteinuria in diabetic hypertension, 17 , 18 left ventricular hypertrophy 19 and CV events. 20 Combined ACEI/CCB treatment was, as anticipated, more efficacious than high doses of the individual agents in increasing arterial compliance and reducing left ventricular mass in patients with hypertension. 19 Significantly greater improvements in large‐vessel compliance were observed with benazepril/amlodipine compared with enalapril monotherapy in patients with hypertension and type 2 diabetes (52% vs 32%; P<.05). 21 In the BP‐lowering arm of the Anglo‐Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial (AS COT), perindopril added to amlodipine was more effective in preventing CV events than was bendroflumethiazide added to atenolol. 20 The amlodipine‐based regimen did not reduce the primary end point of coronary heart disease events but significantly reduced the risk of fatal and nonfatal stroke by 23% (P=.0003), total CV events and procedures by 16% (P<.0001), CV mortality by 24% (P=.0010), all‐cause mortality by 11% (P=.025), and new‐onset diabetes by 30% (P<.0001) compared with atenolol‐based therapy. Of significance was that BP lowering, especially in the first few months of the trial, was greater with amlodipine than with the β‐blocker. Some observers have suggested that the differences in BP may have accounted for at least some of the benefit noted.

Combining ACEIs and CCBs has also been reported to result in a lower incidence of peripheral edema compared with CCB monotherapy. 22 In hypertensive patients aged 65 years or older in long‐term care facilities, a change from high‐dose CCB monotherapy or ACEI/CCB‐free combination therapy to ACEI/CCB FDC reduced the incidence of edema by 75.0% while maintaining BP control. 23

To date, no outcomes trials comparing ACEI/CCB and ACEI/diuretic FDCs have been reported. However, the Avoiding Cardiovascular Events Through Combination Therapy in Patients Living With Systolic Hypertension (ACCOMPLISH) trial is currently under way and compares fixed‐dose benazepril/amlodipine with benazepril/HCTZ in 11,454 high‐risk patients with hypertension. 24 Early results showed a significant reduction from baseline in SBP, and the BP control rates achieved were considered to be the highest of any large multinational study to date. 25

ACEI/CCB combinations may have advantages over ACEI/diuretic combinations in terms of a lower risk of metabolic complications. Diuretics are associated with some increased risk of metabolic adverse effects such as impaired glucose tolerance, hypokalemia, hyperuricemia, and blood lipid changes, especially when used at high doses 26 ; however, there is little evidence that metabolic changes affect CV outcome. 27 CCBs are not generally associated with metabolic adverse effects. In the Trandolapril‐Verapamil in Non‐InsulinDependent Diabetes (TRAVEND) study, trandola‐pril/verapamil demonstrated better metabolic control (glycemic control, glycated hemoglobin) compared with enalapril/HCTZ in patients with type 2 diabetes and albuminuria. 28 Also, in the Study of Trandolapril/Verapamil‐SR and Insulin Resistance (STAR), use of a moderate‐dose thiazide diuretic in hypertensive patients with the metabolic syndrome worsened glycemic control, even when combined with an RAAS blocker, whereas trandolapril/verapamil reduced BP without worsening glycemic control. 29 The implications of these findings in terms of long‐term significance require investigation.

When given as monotherapy, the type of CCB is an important consideration in hypertensive patients with nephropathy associated with proteinuria. A meta‐analysis reported that nondihydropyridine CCBs are preferable to dihydropyridine CCBs when used as monotherapy in this patient population. 18 When combined with an RAAS blocker, however, the type of CCB has been shown not to influence outcome. 30 , 31

ARBs Plus Diuretics

Numerous clinical trials have demonstrated the improved BP ‐lowering efficacy of an ARB given with a diuretic compared with ARB or diuretic monotherapy. For example, valsartan/HCTZ (160/12.5 and 160/25 mg or 320/12.5 and 320/25 mg) produced significantly (P<.05) greater reductions in BP (−27.9/−10.2 mm Hg and −28.3/−10.1 mm Hg) than valsartan monotherapy (−20.7/−6.6 mm Hg) and significantly higher response rates (≈75% vs 59%) in patients with stage 2 or 3 systolic hypertension. 32 , 33 Similarly, the BP ‐lowering efficacy of losartan/HCTZ (50/12.5 mg) has been shown to be significantly greater than losartan monotherapy in patients with mild to moderate 34 and severe 35 hypertension. In another study, irbesartan/HCTZ (300/25 mg/d) significantly reduced (P<.001) SBP and DBP (−22.7/−13.4 mm Hg) in patients with hypertension not controlled with full‐dose single therapy or low‐dose combination therapy. 36 These benefits were expected in view of the specific effects of these agents when given together.

Although no published outcomes trials have prospectively evaluated ARB /diuretic combinations, a high percentage of patients received HCTZ in most of the ARB outcome studies. 37 , 38 , 39 In the Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension (LIFE) study, 70% of patients took HCTZ in addition to the study drug (losartan or atenolol). In the losartan group, the primary composite end point of CV death, myocardial infarction, or stroke was reduced by 13% (P=.021) compared with the atenolol group. 37 Most of the benefit was related to a reduction in stroke incidence. In the Study on Cognition and Prognosis in the Elderly (SCOPE), 59% of candesartan (ARB)‐treated patients and 62% of patients in the placebo group (open‐label antihypertensive therapy added as required) were taking baseline or added HCTZ. 39 The primary composite end points of CV death, myocardial infarction, and stroke were reduced by 11% (P=.19) in the candesartan group compared with non‐ARB therapy (74% received open‐label antihypertensive treatment). In the Valsartan Antihypertensive Long‐Term Use Evaluation (VALUE) in patients aged 50 years or older with untreated or treated hypertension and at high risk for cardiac events, 25% of those treated with the ARB valsartan (and 24% of those treated with amlodipine) received additional HCTZ and 48% (41% in the amlodipine group) received HCTZ and/or other agents. 38 Results showed that despite a greater reduction in BP with amlodipine‐based therapy, there were no significant differences between the 2 treatments in the incidence of the primary end point, defined as cardiac mortality and morbidity (10.6% valsartan vs 10.4% amlodipine, respectively); however, new‐onset diabetes and hospitalization for heart failure favored valsartan therapy. 40 Fewer cases of myocardial infarction were reported for amlodipine, however. 38 The VALUE trial illustrated the importance of early reductions in BP, with a significantly lower risk of cardiac events, stroke, or death in patients classified as “immediate responders,” compared with patients classified as “delayed responders.” 40 Early use of antihypertensive combinations might help to achieve reductions in BP over a shorter time frame since many physicians fail to maximally dose‐titrate individual antihypertensive agents. This primarily relates to real or perceived increases in adverse effects. Consequently, BP goals are not achieved in many patients, or reaching them takes an inordinately long period of time. 41

A disadvantage of initial treatment with most FDCs is the limitation of individual component dosing flexibility. Most FDCs have 2 dose combinations, although there are some with 3 or 4 dose combinations that take full advantage of the fact that physicians should dose‐titrate. Moreover, the higher‐dose FDCs have similar efficacy and better adverse effect profiles than maximum doses of the individual components alone. 9 , 42 Studies have also shown that titration to the maximum dose of a single agent does not provide the same antihypertensive effect as starting with a FDC and titrating the combination. 9 Thus, while most FDCs do not provide much dosing flexibility, some of the newer agents do provide more than enough possibilities to allow for dosing flexibility. Both the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) 2 and the latest European guidelines 43 have supported the concept of 2‐drug therapy as initial treatment in selected patients.

Combining ARBs and HCTZ may attenuate the metabolic effects of thiazide diuretics. 44 For example, hypokalemia is reduced in the presence of an ARB, 45 and the tendency to produce hyperglycemia and new‐onset diabetes mellitus with thiazides may be offset by the effects of ARBs, the use of which has been observed to result in fewer episodes of new‐onset diabetes than some other agents. 37 , 38

Optimizing Efficacy and Tolerability

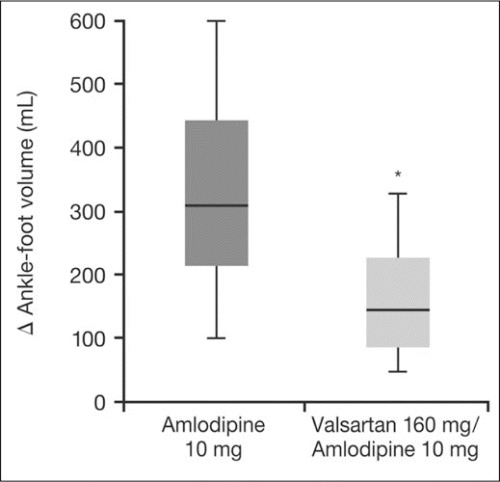

It is well known that even with the use of several different antihypertensive agents, adverse effects may remain an issue. For instance, the frequency of cough with ACEIs remains the same, and the adverse effects of β‐blockers may still occur. The combination of an ARB and a CCB may have a favorable profile because of the good tolerability of ARBs. The efficacy of an ARB/CCB combination compared with ARB or CCB monotherapy to lower BP has been demonstrated in several clinical studies. 46 , 47 A small number of studies have examined combination amlodipine/valsartan therapy. In a crossover study involving 80 patients with grade 1 or 2 hypertension, the efficacy and tolerability of amlodipine/valsartan (10/160 mg) was compared with that of amlodipine (10 mg) and valsartan (160 mg) monotherapy. While both monotherapies significantly (P<.01 vs baseline) reduced SBP (−16.9 and −14.5 mm Hg, respectively) and DBP (−12.9 and −10.2 mm Hg, respectively), this reduction was further increased with amlodipine/valsartan therapy (SBP, −22.9 mm Hg; DBP, −16.8 mm Hg; P<.01). 48 As with many other trials, it was expected that 2‐drug therapy would be more effective than single‐drug treatment. In addition, ankle‐foot volume increase was significantly (P<.01) lower with the combination than with amlodipine alone (Figure 2). The reduction in peripheral edema most likely results from a more balanced arterial and venous dilation during the use of an ARB /CCB combination, compared with a greater dilation of the arteriolar vs venous circulation during CCB monotherapy. 48

Figure 2.

Increases in ankle‐foot volume (AFV) associated with amlodipine and amlodipine/valsartan combination therapy. The thick line is the median value, the upper and lower limits of the rectangle correspond to the standard deviation, and the narrow columns correspond to the upper and lower range limits. *P<.01 vs amlodipine. Adapted with permission from Fogari et al. 48

Another possible benefit of this combination is the potential for an ARB to reduce atrial fibrillation. Data from the LIFE study demonstrate this benefit. 49 In a separate study, 50 therapy with an ARB/CCB combination was found to be more effective than atenolol/amlodipine in preventing new episodes of atrial fibrillation.

CONCLUSIONS

Many patients have hypertension that requires multiple antihypertensive agents to achieve BP targets, and FDCs provide a convenient means of delivering such therapy. This is particularly important in patients with stage 2 hypertension. While many FDCs are available, most clinical evidence supports the use of an RAAS blocker (ACEI or ARB) combined with a diuretic. Some studies of an ACEI/CCB have also reported a reduction in CV events. CCBs may have advantages over diuretics in terms of metabolic changes. It has not been determined whether a thiazide diuretic or CCB with an RAAS blocker is a more effective treatment to reduce events or whether a CCB/RAAS blocker is more resistant to the effect of salt in the diet compared with a thiazide‐based RAAS blocker. It is important to note that all of these combinations provide effective BP control.

Disclosures:

Preparation of this review paper was supported by Novartis Pharma AG. Medical writing and editorial services were provided by Sharon Smalley, principal writer at ACUMED (Macclesfield, UK), and contracted medical writer Paul Hutchin. Dr Weir has acted in a consultancy/advisory capacity and served on the Speakers' Bureau for MSD, BMS/Sanofi, Novartis, and Boehringer‐Ingelheim. Dr Bakris has acted in a consultancy/advisory capacity and served on the Speakers' Bureau for Abbott, Boehringer‐Ingelheim, BMS/Sanofi‐Aventis, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Walgreens (formulary committee), Myogen, and Sankyo. He has also received grants from the National Institutes of Health (The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute), GlaxoSmithKline, Myogen, and Forest.

References

- 1. Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, et al. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005;365:217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Epstein M, Bakris G. Newer approaches to antihypertensive therapy. Use of fixed‐dose combination therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1969–1978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sica DA. Fixed‐dose combination antihypertensive drugs. Do they have a role in rational therapy? Drugs. 1994;48:16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sica DA. Rationale for fixed‐dose combinations in the treatment of hypertension: the cycle repeats. Drugs. 2002;62:443–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moser M, Black HR. The role of combination therapy in the management of hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 1998;11:73S–78S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Connor J, Rafter N, Rodgers A. Do fixed‐dose combination pills or unit‐of‐use packaging improve adherence? A systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:935–939. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weir MR, Levy D, Crikelair N, et al. Time to achieve blood‐pressure goal: influence of dose of valsartan monotherapy and valsartan and hydrochlorothiazide combination therapy. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20:807–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bakris GL, Weir MR. Achieving goal blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes: conventional versus fixed‐dose combination approaches. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2003;5:202–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schmieder RE. Mechanisms for the clinical benefits of angiotensin II receptor blockers. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18(5, pt 1):720–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bertrand ME. Provision of cardiovascular protection by ACE inhibitors: a review of recent trials. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20:1559–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maggioni AP . Efficacy of angiotensin receptor blockers in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2006;20:295–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bellet M, Sassano P, Guyenne T, et al. Converting‐enzyme inhibition buffers the counter‐regulatory response to acute administration of nicardipine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;24:465–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Menard J, Bellet M. Calcium antagonists‐ACE inhibitors combination therapy: objectives and methodology of clinical development. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1993;21(suppl 2):S49–S54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bakris GL, Barnhill BW, Sadler R. Treatment of arterial hypertension in diabetic humans: importance of therapeutic selection. Kidney Int. 1992;41:912–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Malacco E, Piazza S, Carretta R, et al. Comparison of benazepril‐amlodipine and captopril‐thiazide combinations in the management of mild‐to‐moderate hypertension. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;40:263–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bakris GL, Weir MR, DeQuattro V, et al. Effects of an ACE inhibitor/calcium antagonist combination on proteinuria in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 1998;54:1283–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bakris GL, Weir MR, Secic M, et al. Differential effects of calcium antagonist subclasses on markers of nephropathy progression. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1991–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Neutel JM, Smith DH, Weber MA. Effect of antihypertensive monotherapy and combination therapy on arterial distensibility and left ventricular mass. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dahlöf B, Sever PS, Poulter NR, et al. Prevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol adding bendroflumethiazide as required, in the AngloScandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial‐Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT‐BPLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:895–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Winer N, Folker A, Murphy JA, et al. Effect of fixed‐dose ACE‐inhibitor/calcium channel blocker combination therapy vs. ACE‐inhibitor monotherapy on arterial compliance in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes. Prev Cardiol. 2005;8:87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Messerli FH, Oparil S, Feng Z. Comparison of efficacy and side effects of combination therapy of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor (benazepril) with calcium antagonist (either nifedipine or amlodipine) versus high‐dose calcium antagonist monotherapy for systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86:1182–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sapienza S, Sacco P, Floyd K, et al. Results of a pilot pharmacotherapy quality improvement program using fixed‐dose, combination amlodipine/benazepril antihypertensive therapy in a long‐term care setting. Clin Ther. 2003;25:1872–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weber MA, Bakris GL, Dahlöf B, et al. Baseline characteristics in the Avoiding Cardiovascular Events Through Combination Therapy in Patients Living with Systolic Hypertension (ACCOMPLISH) trial: a hypertensive population at high cardiovascular risk. Blood Press. 2007;16:13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jamerson K, Bakris GL, Dahlöf B, et al. Exceptional early blood pressure control rates: the ACCOMPLISH trial. Blood Press. 2007;16:80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Opie LH, Schall R. Old antihypertensives and new diabetes. J Hypertens. 2004;22:1453–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. The ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group . Major outcomes in high‐risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288:2981–2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fernandez R, Puig JG, Rodriguez‐Perez JC, et al. Effect of two antihypertensive combinations on metabolic control in type‐2 diabetic hypertensive patients with albuminuria: a randomised, double‐blind study. J Hum Hypertens. 2001;15:849–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bakris G, Molitch M, Hewkin A, et al. Differences in glucose tolerance between fixed‐dose antihypertensive drug combinations in people with metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2592–2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bakris GL, Weir M, Shanifar S, et al. Effects of blood pressure level on progression of diabetic nephropathy. Results from the RENAAL Study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1555–1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nathan S, Pepine CJ, Bakris GL. Calcium antagonists: effects on cardio‐renal risk in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2005;46:637–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lacourciere Y, Poirier L, Hebert D, et al. Antihypertensive efficacy and tolerability of two fixed‐dose combinations of valsartan and hydrochlorothiazide compared with valsartan monotherapy in patients with stage 2 or 3 systolic hypertension: an 8‐week, randomized, double‐blind, parallelgroup trial. Clin Ther. 2005;27:1013–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weir MR, Crikelair N, Levy D, et al. Evaluation of the dose response with valsartan and valsartan/hydrochlorothiazide in patients with essential hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2007;9:103–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li Y, Liu G, Jiang B, et al. A comparison of initial treatment with losartan/HCTZ versus losartan monotherapy in Chinese patients with mild to moderate essential hypertension. Int J Clin Pract. 2003;57:673–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Salerno CM, Demopoulos L, Mukherjee R, et al. Combination angiotensin receptor blocker/hydrochloro‐thiazide as initial therapy in the treatment of patients with severe hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2004;6:614–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Coca A, Calvo C, Sobrino J, et al. Once‐daily fixed‐combination irbesartan 300 mg/hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg and circadian blood pressure profile in patients with essential hypertension. Clin Ther. 2003;25:2849–2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dahlöf B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet. 2002;359:995–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, Weber M, et al. Outcomes in hypertensive patients at high cardiovascular risk treated with regimens based on valsartan or amlodipine: the VALUE randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363:2022–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lithell H, Hansson L, Skoog I, et al. The Study on Cognition and Prognosis in the Elderly (SCOPE): principal results of a randomized double‐blind intervention trial. J Hypertens. 2003;21:875–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Weber MA, Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, et al. Blood pressure dependent and independent effects of antihypertensive treatment on clinical events in the VALUE trial. Lancet. 2004;363:2049–2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Berlowitz DR, Ash AS, Hickey EC, et al. Inadequate management of blood pressure in a hypertensive population. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1957–1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Weir MR, Ferdinand KC, Flack JM, et al. A noninferiority comparison of valsartan/hydrochlorothiazide combination versus amlodipine in black hypertensives. Hypertension. 2005;46:508–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. 2007 guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2007;25:1105–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kjeldsen SE, Os I, Hoieggen A, et al. Fixed‐dose combinations in the management of hypertension: defining the place of angiotensin receptor antagonists and hydrochlorothiazide. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2005;5:17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pool JL, Glazer R, Weinberger M, et al. Comparison of valsartan/hydrochlorothiazide combination therapy at doses up to 320/25 mg versus monotherapy: a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study followed by long‐term combination therapy in hypertensive adults. Clin Ther. 2007;29(1):61–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Andreadis EA, Tsourous GI, Marakomichelakis GE, et al. High‐dose monotherapy vs low‐dose combination therapy of calcium channel blockers and angiotensin receptor blockers in mild to moderate hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2005;19:491–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Stergiou GS, Makris T, Papavasiliou M, et al. Comparison of antihypertensive effects of an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor, a calcium antagonist and a diuretic in patients with hypertension not controlled by angiotensin receptor blocker monotherapy. J Hypertens. 2005;23:883–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fogari R, Zoppi A, Derosa G, et al. Effect of valsartan addition to amlodipine on ankle oedema and subcutaneous tissue pressure in hypertensive patients. J Hum Hypertens. 2007;21:220–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wachtell K, Lehto M, Gerdts E, et al. Angiotensin II receptor blockade reduces new‐onset atrial fibrillation and subsequent stroke compared to atenolol: the Losartan Intervention For End Point Reduction in Hypertension (LIFE) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:712–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mugellini A, Preti P, Destro M, et al. Valsartan amlodipine combination and prevention of atrial fibrillation recurrence in hypertensive diabetic patients [abstract]. J Hypertens. 2006;24(suppl 4):S5. [Google Scholar]