Abstract

Background: Gut microbiota are considered to be intrinsic regulators of thyroid autoimmunity. We designed a cross-sectional study to examine the makeup and metabolic function of microbiota in Graves' disease (GD) patients, with the ultimate aim of offering new perspectives on the diagnosis and treatment of GD.

Methods: The 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) V3–V4 DNA regions of microbiota were obtained from fecal samples collected from 45 GD patients and 59 controls. Microbial differences between the two groups were subsequently analyzed based on high-throughput sequencing.

Results: Compared with controls, GD patients had reduced alpha diversity (p < 0.05). At the phylum level, GD patients had a significantly lower proportion of Firmicutes (p = 0.008) and a significantly higher proportion of Bacteroidetes (p = 0.002) compared with the controls. At the genus level, GD patients had greater numbers of Bacteroides and Lactobacillus, although fewer Blautia, [Eubacterium]_hallii_group, Anaerostipes, Collinsella, Dorea, unclassified_f_Peptostreptococcaceae, and [Ruminococcus]_torques_group than controls (all p < 0.05). Subgroup analysis of GD patients revealed that Lactobacillus may play a key role in the pathogenesis of autoimmune thyroid diseases. Nine distinct genera showed significant correlations with certain thyroid function tests. Functional prediction revealed that Blautia may be an important microbe in certain metabolic pathways that occur in the hyperthyroid state. In addition, linear discriminant analysis (LDA) and effect size (LEfSe) analysis showed that there were significant differences in the levels of 18 genera between GD patients and controls (LDA >3.0, all p < 0.05). A diagnostic model using the top nine genera had an area under the curve of 0.8109 [confidence interval: 0.7274–0.8945].

Conclusions: Intestinal microbiota are different in GD patients. The microbiota we identified offer an alternative noninvasive diagnostic methodology for GD. Microbiota may also play a role in thyroid autoimmunity, and future research is needed to further elucidate the role.

Keywords: Graves' disease, gut microbiota, 16S rRNA sequencing, alpha diversity, metabolism

Introduction

The human intestine is colonized with a large number of complex bacteria, which, together with a small number of viruses and fungi, constitute the intestinal microbiome (1). These gut microbiota play an active role in human health through regulating the immune system, digestion, and inhibiting nefarious colonizing pathogens (2). Recently, many researchers have found links between the microbiota and many diseases affecting the immune and endocrine systems, such as obesity, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and rheumatoid arthritis (3–6).

The gut, as the largest endocrine organ, plays an often neglected but important role in the occurrence and development of autoimmune thyroid diseases (AITD) (7–10). Graves' disease (GD), which is the most frequent cause of hyperthyroidism, and Hashimoto's thyroiditis are both common AITD. The role of microbiota in AITD is thought to be the cross-reactivity between certain microbe antigens and self-antigens (11,12). Kiseleva et al. showed that certain Lactobacillus B-01 and Bifidobacterium 791 protein sequences have structural similarities with those of thyroid peroxidase (TPO) and thyroglobulin (TG). These microbiota can selectively bind TPO antibody (TPOAB) and TG antibody (TGAB) through “molecular mimicry mechanisms,” which then induces AITD (12). In addition, studies have shown that some microbiota and their metabolites can penetrate the intestinal barrier and enter the blood, thereby promoting the release of inflammatory cytokines, and influence the host immune function (13). Taken together, these findings suggest that alterations in the gut microbiome may result in chronic intestinal inflammation and immune activation, ultimately resulting in AITD.

As one of the most common AITD, GD may result in goiter, hyperthyroidism, eye disease manifested as proptosis, pretibial edema, and an elevated metabolic state, which can seriously endanger human health. The major immunological feature of GD is the presence of thyroid stimulating hormone receptor antibodies (TRAB). Although the etiology and pathogenesis of GD are yet to be fully elucidated, it is generally believed that GD develops secondary to certain immunologic, genetic, and environmental factors. It is also speculated that microbial disorders caused by thyroid hormones may be closely related to thyroid autoimmunity. Consequently, immune dysfunction may exacerbate the imbalance of microbiota and thyroid hormone disorders, resulting in the progression of GD. Furthermore, environmental factors can impact gut microbiota, indirectly promoting the development of GD. Despite the significant evidence linking gut microbiota and AITD, there are few studies examining the association between microbiota and GD. Therefore, this cross-sectional study aimed to determine the abundance and diversity of gut microbiota in GD patients and their potential associations with thyroid function tests, as well as related functional metabolic pathways. This research may provide a basis for the pathogenesis of GD and, therefore, may have prognostic and treatment implications.

Materials and Methods

Patients and samples

Informed consent was obtained from all study subjects. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Tenth People's Hospital (SHSY-IEC-KY-4.0/16–18/01) and conducted in accordance with the guidelines provided by the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Forty-five untreated GD patients (12 males, 33 females, ages 16–65 years, median age 37) were recruited from the Department of Nuclear Medicine at the Shanghai Tenth People's Hospital from January to June 2019. Fifty-nine healthy volunteers (22 males, 37 females, age 22–71 years, median age 43) were recruited as controls from the health screening center at our hospital, and all controls were free of thyroid disease based on ultrasound examination and thyroid function tests. The volunteers were matched with the GD patients in terms of age and sex. GD inclusion criteria were based on ATA guidelines (14) and included the following: (i) increased thyroid hormone concentration and decreased serum thyrotropin (TSH) concentration, (ii) diffuse thyroid enlargement and increased vascularity by ultrasonography, and (iii) serum TRAB positive. At the time of the study, no subjects had malignancies, gastrointestinal diseases, or other endocrine system diseases. No antibiotics, probiotics, or prebiotics were used by any of the subjects 1 month before fecal sampling. Subjects fasted overnight (≥8 hours), and fecal samples were collected and stored at −80°C until DNA extraction. Demographic information and clinical data were also collected.

Assays of thyroid function and thyroid-related autoantibodies

Serum levels of free triiodothyronine (fT3), free thyroxine (fT4), total triiodothyronine (TT3), total thyroxine (TT4), TSH, TGAB, TPOAB, thyroid microsomal antibody (TMAB), and TRAB were assayed by chemiluminescent immunoassays (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). Reference ranges were defined as follows: fT3 2.80–6.30 pmol/L; fT4 10.50–24.40 pmol/L; TT3 1–3 nmol/L; TT4 55.50–161.30 nmol/L; TSH 0.38–4.34 mIU/L; TGAB 0.00–110 IU/mL; TPOAB 0.00–40 IU/mL; TMAB 0.16–10 IU/mL; and TRAB 0.00–1.75 IU/L.

DNA extraction

Microbial DNA was extracted from 104 fecal samples using the E.Z.N.A.® soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA) according to the manufacturer's protocols. The NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific) was used to determine the concentration and purity of the bacterial DNA. The extracted DNA was stored at −20°C until experiments were conducted.

Polymerase chain reaction amplification and MiSeq sequencing

The V3–V4 hypervariable regions of the bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes were amplified with the primers 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) using the thermocycler polymerase chain reaction system (GeneAmp 9700; ABI, Waltham, MA) (15). Each sample was amplified three times to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the subsequent data analysis. The amplicon was further purified using the AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen Biosciences, Union City, CA), and quantitative analysis was performed using QuantiFluor™-ST (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The purified amplicons were combined at equimolar concentrations and subjected to end-pair sequencing analysis using the Illumina MiSeq PE300 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA).

Microbial analysis

The paired-end reads obtained by MiSeq were first merged by overlapping sequences. The sequences were then optimized using filtering and quality control. Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were clustered using a 97% similarity cutoff with UPARSE (version 7.1), and chimeric sequences were identified and removed using UCHIME. The taxonomy of each sequence was annotated using the RDP Classifier (version 2.2) in conjunction with the Silva database, with a confidence threshold of 70%. OTUs with <0.005% of the total number of sequences were deleted to reduce the effect of spurious sequences on the results (16). The alpha diversity was analyzed based on the species' richness at the OTU level, including SOBs, CHAO, SHANNON, ACE, SIMPSON, and COVERAGE. The unweighted UniFrac algorithm was used to analyze structural differences between the samples using the β-diversity, which was mapped using principal coordinate analysis.

Statistical analysis

R package (version3.4.3) was used to process data. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to analyze whether the diversity index and microbiota abundance between the two groups were significantly different. The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to examine for correlations between the microbiota and thyroid function tests as well as certain metabolic pathways. A random forest model was used to select the genera that would distinguish patients with GD from controls optimally based on linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) analysis. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was drawn and the area under the curve (AUC) reflected the diagnostic accuracy of the random forest model. The difference was considered statistically significant only when the average abundance level of the species was >1% and p < 0.05.

Results

Study population

A total of 45 GD patients and 59 controls were recruited. There were no significant differences in age and sex between the two groups of subjects. Summarized in Table 1 are the clinical and demographic data in the two groups.

Table 1.

Graves' Disease Patients' Thyroid Function Tests

| Parameters | GD group (n = 45) | Control group (n = 59) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range) | 37 (16–65) | 43 (22–71) | 0.198 |

| Sex (male/female) | 12/33 | 22/37 | 0.257 |

| fT3 (2.80–6.30 pmol/L), mean ± SD | 20.04 ± 8.69 | 3.64 ± 0.47 | <0.001 |

| fT4 (10.50–24.40 pmol/L), mean ± SD | 49.23 ± 24.46 | 12.90 ± 1.37 | <0.001 |

| TT3 (1.00–3.00 nmol/L), mean ± SD | 6.23 ± 2.81 | 1.83 ± 0.49 | <0.001 |

| TT4 (55.50–161.30 pmol/L), mean ± SD | 235.06 ± 82.99 | 78.96 ± 12.47 | <0.001 |

| TSH (0.38–4.34 mIU/L), mean ± SD | 0.04 ± 0.11 | 2.25 ± 0.99 | <0.001 |

| TGAB (0.00–110 IU/mL), mean ± SD | 296.51 ± 408.30 | 5.19 ± 2.56 | <0.001 |

| TPOAB (0.00–1.75 IU/mL), mean ± SD | 217.37 ± 148.21 | 0.90 ± 0.47 | <0.001 |

| TMAB (0.00–40 IU/mL), mean ± SD | 61.51 ± 41.43 | 5.07 ± 2.66 | <0.001 |

| TRAB (0.16–10 IU/L), mean ± SD | 18.98 ± 14.71 | 2.38 ± 1.29 | <0.001 |

fT3, free triiodothyronine; fT4, free thyroxine; GD, Graves' disease; SD, standard deviation; TGAB, thyroglobulin antibody; TMAB, thyroid microsomal antibody; TPOAB, thyroid peroxidase antibody; TRAB, thyroid stimulating hormone receptor antibody; TSH, thyrotropin; TT3, total triiodothyronine; TT4, total thyroxine.

GD patients have reduced alpha diversity and abundances of certain microbiota compared with healthy controls

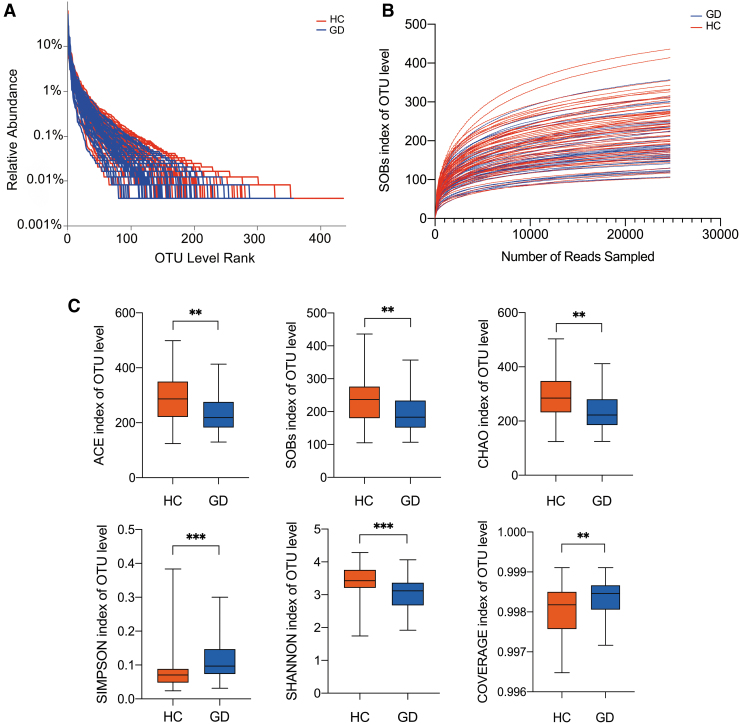

High-throughput sequencing results of the 16S rRNA V3–V4 hypervariable regions obtained from stool samples showed that the tested taxa were rich, including 13 phyla, 261 genera, and 995 OTUs. Rank-abundance curves based on OTU level showed that the species were distributed evenly and richly (Fig. 1A). A rarefaction curve was used to compare the richness, homogeneity, and diversity of fecal samples with the amount of sequencing data, as well as to demonstrate that the amount of sequencing data was adequate. Figure 1B shows that the curves tended to be flat as the sample sizes increased, indicating that the sequencing data were adequate and appropriately reflective of the microbial diversity. Both groups exhibited greater than 99.6% coverage, suggesting that the sequencing depth was saturated (Fig. 1C). Based on the analysis of alpha diversity at the OTU level, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test results showed that GD patients had reduced diversity and abundances of certain microbiota than control subjects. The SOBs, CHAO, and ACE indices, which all reflect abundance, were all significantly lower in GD patients compared with controls (p = 0.002, 0.001, and 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, the SHANNON and SIMPSON indices, which reflect alpha diversity, were significantly lower and higher in GD patients, respectively (p < 0.0001, respectively) (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

General sequencing characteristics of the 105 fecal samples and comparison of alpha diversity in GD patients and HC. (A) Rank-abundance curves of the gut microbiota at the OTU level. (B) Rarefaction curves (SOBs index) of the gut microbiota at the OTU level. (C) Comparison of alpha diversity in GD patients and HC at the OTU level. The SOBs, CHAO, and ACE indices reflect the abundance of microbiota. The SHANNON and SIMPSON indices reflect the alpha diversity, and the COVERAGE index reflects the sequence coverage. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. GD, Graves' disease; HC, healthy controls; OTU, operational taxonomic unit.

Changes in the composition of gut microbiota in GD patients

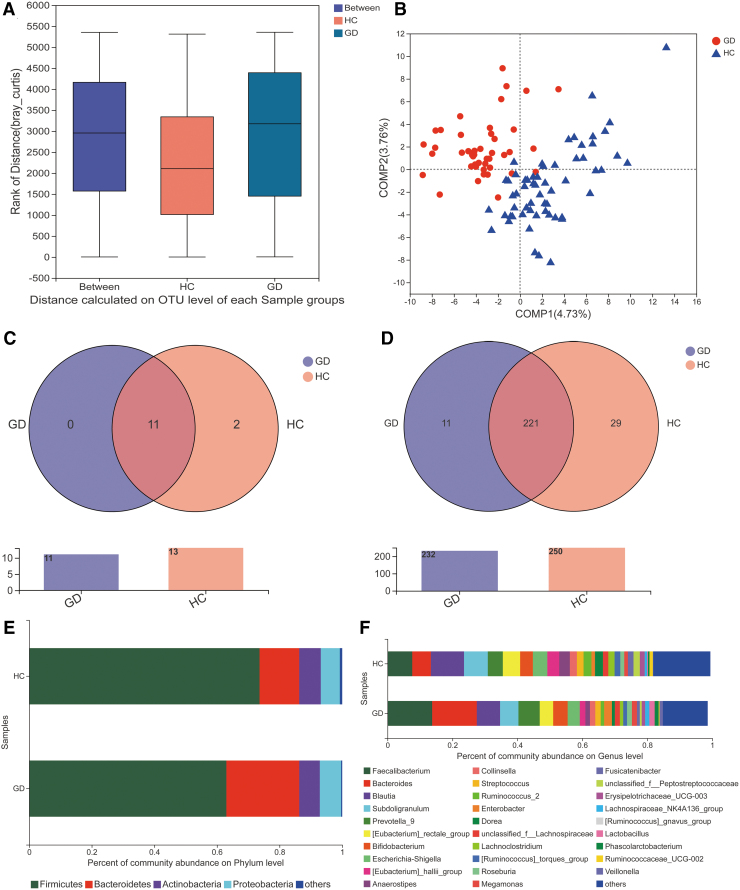

Analysis of similarities showed a statistically significant difference between the groups (i.e., the difference between the groups was greater than that of within each group, p = 0.001, Fig. 2A). Analysis of beta diversity using partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) revealed that the microbial composition of GD patients was significantly different than that of controls (Fig. 2B). We further determined the taxon compositions of the two groups (Fig. 2C, D). A total of 13 phyla and 261 genera were sequenced. Eleven of the 13 phyla were present in samples from both groups, while the remaining 2 were unique to the control group, namely p_Nitrospinae and p_Spirochaetae. A total of 221 genera were present in samples from both groups, while 29 genera were unique to the control group and 11 genera were unique to the GD group (including g_Negativicoccus, g_Bacillus, g_Succiniclasticum). Figure 2E shows that Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes were the two dominant phyla in both GD patients and controls. However, the proportion of Firmicutes was lower in GD patients than in controls. Conversely, the proportion of Bacteroidetes was higher in GD patients than in controls. At the genus level, GD patients had greater numbers of Faecalibacterium, Bacteroides, Prevotella_9, and Bifidobacterium and lower numbers of Blautia, Subdoligranulum, [Eubacterium]_rectale_group (Fig. 2F).

FIG. 2.

Altered composition of gut microbiota in GD patients compared with HC. (A) ANOSIM showed that the difference between the GD patients and the HC was significant (p = 0.001) at the OTU level. (B) Analysis of beta diversity using PLS-DA revealed that the microbial composition found in GD patients clearly differed from that found in HC. One dot in the figure represents one sample. (C) The species Venn diagram at the phylum level. Overlapping parts in the figure indicate common species. (D) The species Venn diagram at the genus level. (E) Composition of the gut microbiota at the phylum level. (F) Composition of the gut microbiota at the genus level. ANOSIM, analysis of similarities; PLS-DA, partial least squares discriminant analysis.

Statistical analysis of taxon differences between GD patients and healthy controls

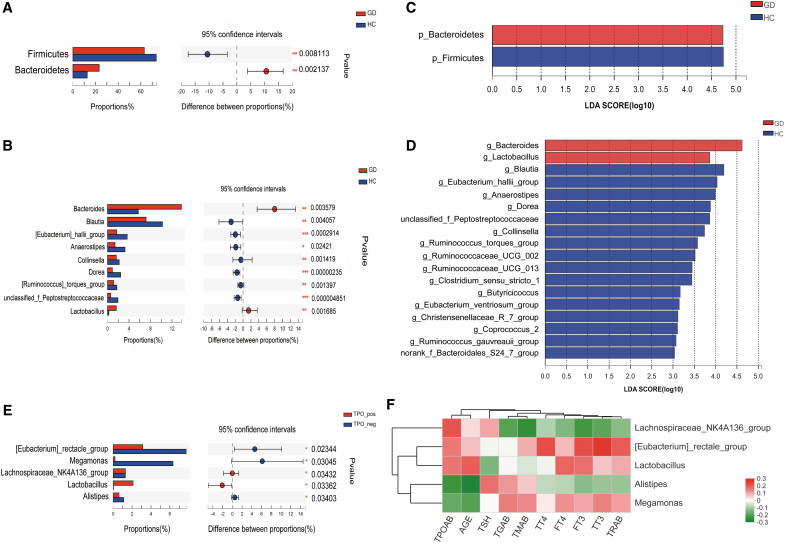

We used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to identify which specific microbiota levels were significantly different between the two groups (average abundance level >1%, p < 0.05). As shown in Figure 3A, compared with controls, GD patients had significantly lower levels of Firmicutes (p = 0.008) and significantly higher levels of Bacteroidetes (p = 0.002). At the genus level, GD patients had significantly higher levels of Bacteroides and Lactobacillus and significantly lower levels of Blautia, [Eubacterium]_hallii_group, Anaerostipes, Collinsella, Dorea, unclassified_f_Peptostreptococcaceae, and [Ruminococcus]_torques_group (all p < 0.05, Fig. 3B). In addition, we identified two phyla and 18 genera that could significantly distinguish the two groups by LEfSe analysis (linear discriminant analysis [LDA] >3.0, all p < 0.05, Fig. 3C, D).

FIG. 3.

Statistical analysis of taxa across GD patients and HC. (A, B) Comparison between the two groups at the phylum and genus levels. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. (C, D) The LEfSe was used to identify the species that significantly differed between GD patients and HC at the phylum and genus levels. Only taxa meeting a significant LDA threshold value of >3 and p < 0.05 are shown. (E) Comparison across GD subgroups (GD with and without Hashimoto's thyroiditis). (F) Correlation heat-map analysis between genera and thyroid function tests. Red represents a positive correlation, and green represents a negative correlation. LDA, linear discriminant analysis; LEfSe, linear discriminant analysis effect size.

The GD group was further subdivided into GD with Hashimoto's thyroiditis, positive group (n = 35), and GD without Hashimoto's thyroiditis, negative group (n = 10), according to whether or not the subject's TPOAB level was greater than 40 IU/mL. Five genera showed significant differences between the two subgroups, of which, Lactobacillus levels, in the positive group, were increased significantly (all p < 0.05, Fig. 3E). Correlation heat-map analysis also showed that Lactobacillus levels were positively correlated with TPOAB and TRAB levels, although the results were not statistically significant (r = 0.156, 0.092, respectively, both p > 0.05, Fig. 3F).

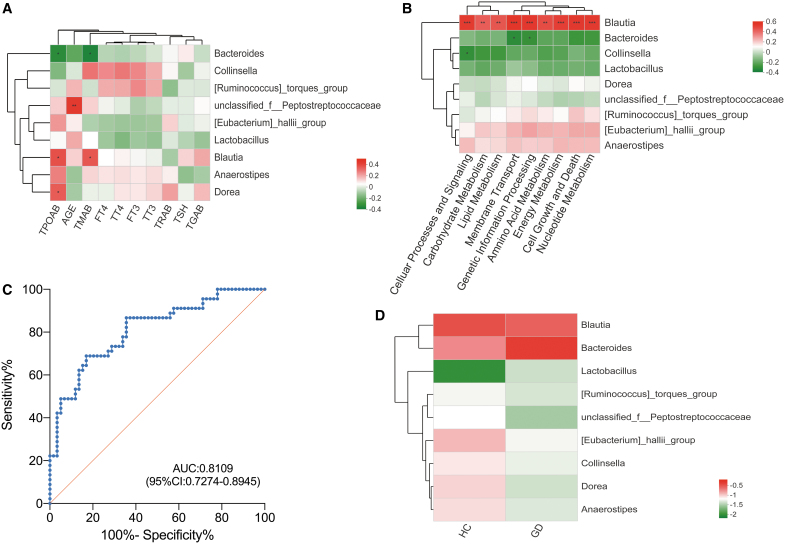

Pearson correlation analysis and PICRUSt prediction

Based on the above results, we examined the relationship between thyroid function tests and levels of the following microbiota: Bacteroides, Lactobacillus, Blautia, [Eubacterium]_hallii_group, Anaerostipes, Collinsella, Dorea, unclassified_f_Peptostreptococcaceae, and [Ruminococcus]_torques_group. We then attempted to delineate the functional impact of these flora by using the KEGG database to identify what biological pathways they may be involved in. Pearson correlation coefficient testing demonstrated that Blautia, Dorea, and Bacteroides levels significantly correlated with certain thyroid function tests (Fig. 4A). Blautia positively correlated with TPOAB (r = 0.365, p = 0.014) and TMAB (r = 0.350, p = 0.019) levels, while Bacteroides negatively correlated with TPOAB (r = −0.342, p = 0.021) and TMAB (r = −0.364, p = 0.014) levels. Dorea negatively correlated with TPOAB levels (r = 0.341, p = 0.022). In addition, unclassified_f_Peptostreptococcaceae positively correlated with age (r = 0.428, p = 0.003). Subsequently, we standardized the OTU abundance table with PICRUSt to obtain KEGG pathway information regarding predictions of metabolic function in nine specific areas. These included lipid metabolism, amino acid metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism, cell growth and death, cellular processes and signaling, energy metabolism, nucleotide metabolism, genetic information processing, and membrane transport. Figure 4B shows that Blautia strongly positively correlated with all nine of these metabolic functions (all p < 0.01). Furthermore, Bacteroides negatively correlated with membrane transport and genetic information processing (both p < 0.05), and Collinsella negatively correlated with cellular processes and signaling (p < 0.05).

FIG. 4.

The relationship between the predictive genera identified by LEfSe and thyroid function tests as well as metabolic functions. (A) Pearson correlation analysis was used to determine the relationships between genera and thyroid function tests. Red represents a positive correlation, and green represents a negative correlation. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. (B) Pearson correlation analysis was used to determine the relationships between genera and metabolic functions. Red represents a positive correlation, and green represents a negative correlation. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. (C) The ROC curve was used to assess the diagnostic accuracy of the top nine genera based on LEfSe results. (D) Species cluster analysis confirmed that the two groups could be distinguished by these nine specific microbiota. fT3, free triiodothyronine; fT4, free thyroxine; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; TG, thyroglobulin; TGAB, thyroglobulin antibody; TMAB, thyroid microsomal antibody; TPOAB, thyroid peroxidase antibody; TRAB, thyroid stimulating hormone receptor antibody; TSH, thyrotropin; TT3, total triiodothyronine; TT4, total thyroxine.

ROC curve analysis to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of specific intestinal microbiota

LEfSe analysis revealed 18 specific genera that differed significantly between GD patients and controls (LDA >3, all p < 0.05, Fig. 3D). We selected the top nine microbiota to serve as diagnostic biomarkers according to random forest analysis, including Bacteroides, Blautia, [Eubacterium]_hallii_group, Anaerostipes, Lactobacillus, Dorea, unclassified_f_Peptostreptococcaceae, Collinsella, and [Ruminococcus]_torques_group. ROC curves were generated to assess the diagnostic accuracy of these nine species (AUC value of 0.8109 [confidence interval: 0.7274–0.8945]) (Fig. 4C). Species cluster analysis also demonstrated that the two groups could be distinguished by each of the nine specific microbiota (Fig. 4D).

Discussion

In this study, fecal samples collected from 45 untreated GD patients and 59 healthy volunteers were subjected to high-throughput 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Sequencing results were reflective of the subjects' intestinal microbiota. Alpha diversity analysis at the OTU level revealed that GD patients have a significantly reduced richness of gut microbiota compared with healthy controls. Similar findings have been observed in IBD (17), hypertension (18), and autoimmune hepatitis (19). It is thought that lower alpha diversity may lead to a decline in the host's immune function and is associated with an inflammatory response. In this study, PLS-DA was also performed to demonstrate the difference in microbial composition between GD patients and healthy controls.

Through a statistical analysis of 13 phyla, 261 genera, and 995 OTUs, the microbiota of GD patients were found to harbor specific characteristics. At the phylum level, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes were the dominant microbiota in both groups. The proportion of Firmicutes was lower in the GD group than in the control group, while the proportion of Bacteroidetes was higher in the GD group than in the control group. Interestingly, previous research has found that obese people have a greater proportion of Firmicutes, while lean people have a greater proportion of Bacteroidetes (20,21). Thus, we speculate that in addition to increasing the basal metabolic rate, thyroid hormones may also impact the composition and function of microbiota, which in turn lead to changes in a person's weight. At the genus level, there were significant differences in the levels of nine species between the two groups. Compared with the control group, Bacteroides and Lactobacillus levels were increased in GD patients, while the levels of Blautia, [Eubacterium]_hallii_group, Anaerostipes, Collinsella, Dorea, [Ruminococcus]_torques_group, and unclassified_f_Peptostreptococcaceae were reduced.

Bacteroides can produce SCFAs other than butyric acid, including succinate, propionate, and acetate, which cannot induce mucin synthesis. This leads to reduced intestinal tight junctions and increased permeability of the intestinal mucosa (22). Therefore, we hypothesize that the increased levels of Bacteroides and its metabolites impair intestinal barrier function, resulting in the release of a large number of proinflammatory factors outside the intestine and causing immune dysfunction. In this way, Bacteroides may play an auxiliary role in the pathophysiology of GD. Interestingly, an increased abundance of Bacteroides has also consistently been observed in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (23).

Lactobacillus levels were also found to be significantly elevated in GD patients, consistent with prior research showing elevated levels of Lactobacillus in autoimmune hepatitis (19). Although Lactobacillus is a recognized probiotic, research has shown that certain strains of Lactobacillus are potentially pathogenic (e.g., resulting in bacteremia, infective endocarditis) (24). Miettinen et al. also found that Lactobacillus can directly activate the NF-κB signaling pathway (25). Therefore, depending on the virulence of the strain, Lactobacillus may play a nefarious role in GD through activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway. We observed from patients' thyroid function tests that some GD patients have elevated TPOAB levels, suggesting that these patients also have Hashimoto's thyroiditis. We performed a subgroup analysis of these patients to further analyze the role of microbiota in the thyroid autoimmunity response. The significantly increased levels of Lactobacillus in GD with Hashimoto's thyroiditis subjects were surprising. While a positive correlation between Lactobacillus levels and TPOAB levels was observed, the results were not statistically significant. Because some strains of Lactobacillus have amino acid sequences homologous to TPO and TG, in GD and Hashimoto's thyroiditis, we propose the following: the increased abundance of Lactobacillus caused by altered thyroid hormone levels activates proinflammatory signaling pathways and an autoimmune response against the thyroid. Subsequent thyroid dysfunction further aggravates the gut microbiota imbalance, leading to a ‘vicious’ cycle of worsening inflammation and thyroid dysfunction.

Studies have shown that [Eubacterium]_hallii_group and Anaerostipes use lactic acid to produce butyric acid and thereby maintain the integrity of the intestinal epithelium as well as induce the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells (Tregs) to strengthen the tightness of the intestinal mucosal barrier (26,27). Blautia is a member of the Lachnospiraceae family, and its main metabolite is butyric acid. Studies have shown that increased Blautia levels are associated with a reduction in mortality from acute graft-versus-host disease and an increase in overall survival in patients who have received bone marrow transplantation. It is speculated that Blautia plays an anti-inflammatory role (28), which is consistent with our findings that Blautia, [Eubacterium]_hallii_group, and Anaerostipes levels are reduced in GD patients. Along the same lines, Prior research has shown that levels of these bacteria are also reduced in IBD and tuberculosis patients (29). Therefore, we hypothesize that the reduction of butyrate in the intestine from the drop in numbers of these three butyric acid-producing microbiota inhibits the differentiation of Tregs. This results in the displacement of microbiota and their metabolites, the activation of an inflammatory response by the immune system, and eventually the triggering of AITD.

A review of the literature identified a few studies on Dorea, primarily in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) patients. Velázquez et al. (30) found that Dorea levels were significantly elevated in NASH patients, whereas Da Silva (31) reported that Dorea levels were reduced in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Research on Dorea's relationship with GD and its role in metabolism is considerably limited at this time.

It has been reported that the increased permeability of the intestinal mucosa, regulation of intestinal motility, reduced expression of tight junction proteins in epithelial cells, and release of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-17 are pathways by which Collinsella leads to disease (32). Our finding that GD patients have reduced Collinsella levels contrasts with the elevated levels seen in patients with obesity, NASH, atherosclerosis, and other diseases (33).

Reduced levels of [Ruminococcus]_torques_group is probably one of the principal reasons for the drop in Firmicutes levels observed in the GD group. In a study on abdominal obesity, it was found that [Ruminococcus]_torques_group levels decrease with decreasing body fat (34). Therefore, it is thought that [Ruminococcus]_torques_group works in conjunction with Bacteroides, under the influence of thyroid hormone, to alter fat metabolism in GD patients. We also found that the abundance of unidentified Peptostreptococcaceae was significantly reduced in GD patients. It has been reported that Peptostreptococcus is a part of the normal flora in the human oral cavity, upper respiratory tract, intestinal tract, and female reproductive tract (35). As such, a reduced abundance may potentially affect host health. However, there are few studies on Peptostreptococcaceae, and its role in GD has not been studied.

We examined the relationship between certain microbiota and thyroid function tests, including triiodothyronine (T3), thyroxine (T4), TSH, TRAB, TGAB, TPOAB, and TMAB. Blautia levels positively correlated with TPOAB and TMAB levels, while Bacteroides negatively correlated with TPOAB and TMAB levels. Dorea levels inversely correlated with TPOAB levels. These findings suggest that it is possible that microbiota can influence the development of GD through stimulation of an autoimmune response against the thyroid gland.

The KEGG metabolic function correlation analysis revealed that Blautia is strongly related to nine functional pathways. Studies have shown that an imbalance in intestinal microbiota can affect the host's health in many ways, including energy metabolism, lipid metabolism, and signaling pathways. As mentioned above, Blautia is a butyric acid-producing bacterium playing an active role in host health. Byndloss et al. (36) demonstrated that butyric acid maintains the intestinal anaerobic environment and intestinal health through activation of β-oxidation and inhibition of the expression of nitric oxide synthase encoding gene (NOS2) via PPAR-γ signaling in colonic epithelial cells. As in the intestine, PPAR-γ activation inhibits Th1 proinflammatory cytokines in the thyroid as well (37). Reduced Blautia levels result in decreased butyrate, leading to metabolic dysfunction, decreased activation of PPAR-γ signaling, increased intestinal mucosal permeability, and reduced free radical degradation, thus preventing normal immune function and ultimately possibly inducing AITD. It is also notable that through the transport of lipopolysaccharides and bacterial fragments from the gut into the blood, vessel walls, and organs, gut microbiota may induce a low-grade chronic inflammatory response, which can eventually lead to disease (38).

The top nine species predicted by LEfSe analysis coincide with the nine genera that differ between the two groups. These nine genera could be used to accurately distinguish GD patients from controls with an AUC value of 0.8109. Species cluster analysis confirmed these results as well.

Our study provides evidence of the role of gut microbiota in the development of GD. In addition to a theoretical basis for the pathogenesis of GD, our results have diagnostic, treatment, and prognostic implications. The small number of recruited subjects (45 patients and 59 healthy volunteers) is a limitation of our study. There is also some uncertainty as to whether the microbiota extracted from the subjects' fecal samples reflects the true extent of the intestinal microbiome. Sequencing of V3–V4 fragments of DNA to quantitatively detect the relative abundance of microbiota may not accurately reflect the true proportions of each species. The biological functions, metabolic mechanisms, and precise molecular pathways that intestinal microbiota are involved in remain to be determined. As such, further study is necessary to determine how gut microbiota and GD are linked as well as how such links may aid in the diagnosis and treatment of GD.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all subjects for taking part in our research.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Funding Information

This study has not received funding.

References

- 1. Ley RE, Peterson DA, Gordon JI. 2006. Ecological and evolutionary forces shaping microbial diversity in the human intestine. Cell 124:837–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Round JL, Mazmanian SK. 2009. The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 9:313–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Isolauri E 2017. Microbiota and obesity. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser 88:95–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kostic AD, Gevers D, Siljander H, Vatanen T, Hyotylainen T, Hamalainen AM, Peet A, Tillmann V, Poho P, Mattila I, Lahdesmaki H, Franzosa EA, Vaarala O, de Goffau M, Harmsen H, Ilonen J, Virtanen SM, Clish CB, Oresic M, Huttenhower C, Knip M, Xavier RJ. 2015. The dynamics of the human infant gut microbiome in development and in progression toward type 1 diabetes. Cell Host Microbe 17:260–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sokol H, Leducq V, Aschard H, Pham HP, Jegou S, Landman C, Cohen D, Liguori G, Bourrier A, Nion-Larmurier I, Cosnes J, Seksik P, Langella P, Skurnik D, Richard ML, Beaugerie L. 2017. Fungal microbiota dysbiosis in IBD. Gut 66:1039–1048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang X, Zhang D, Jia H, Feng Q, Wang D, Liang D, Wu X, Li J, Tang L, Li Y, Lan Z, Chen B, Li Y, Zhong H, Xie H, Jie Z, Chen W, Tang S, Xu X, Wang X, Cai X, Liu S, Xia Y, Li J, Qiao X, Al-Aama JY, Chen H, Wang L, Wu QJ, Zhang F, Zheng W, Li Y, Zhang M, Luo G, Xue W, Xiao L, Li J, Chen W, Xu X, Yin Y, Yang H, Wang J, Kristiansen K, Liu L, Li T, Huang Q, Li Y, Wang J. 2015. The oral and gut microbiomes are perturbed in rheumatoid arthritis and partly normalized after treatment. Nat Med 21:895–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhao F, Feng J, Li J, Zhao L, Liu Y, Chen H, Jin Y, Zhu B, Wei Y. 2018. Alterations of the gut microbiota in Hashimoto's thyroiditis patients. Thyroid 28:175–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhou L, Li X, Ahmed A, Wu D, Liu L, Qiu J, Yan Y, Jin M, Xin Y. 2014. Gut microbe analysis between hyperthyroid and healthy individuals. Curr Microbiol 69:675–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Frohlich E, Wahl R. 2019. Microbiota and thyroid interaction in health and disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab 30:479–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ahlman H, Nilsson 2001. The gut as the largest endocrine organ in the body. Ann Oncol 12(Suppl 2):S63–S68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Benvenga S, Guarneri F. 2016. Molecular mimicry and autoimmune thyroid disease. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 17:485–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kiseleva EP, Mikhailopulo KI, Sviridov OV, Novik GI, Knirel YA, Szwajcer Dey E. 2011. The role of components of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus in pathogenesis and serologic diagnosis of autoimmune thyroid diseases. Benef Microbes 2:139–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lv LX, Fang DQ, Shi D, Chen DY, Yan R, Zhu YX, Chen YF, Shao L, Guo FF, Wu WR, Li A, Shi HY, Jiang XW, Jiang HY, Xiao YH, Zheng SS, Li LJ. 2016. Alterations and correlations of the gut microbiome, metabolism and immunity in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Environ Microbiol 18:2272–2286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ross DS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, Greenlee MC, Laurberg P, Maia AL, Rivkees SA, Samuels M, Sosa JA, Stan MN, Walter MA. 2016. 2016 American Thyroid Association guidelines for diagnosis and management of hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid 26:1343–1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, Gevers D, Miropolsky L, Garrett WS, Huttenhower C. 2011. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol 12:R60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Navas-Molina JA, Peralta-Sanchez JM, Gonzalez A, McMurdie PJ, Vazquez-Baeza Y, Xu Z, Ursell LK, Lauber C, Zhou H, Song SJ, Huntley J, Ackermann GL, Berg-Lyons D, Holmes S, Caporaso JG, Knight R. 2013. Advancing our understanding of the human microbiome using QIIME. Methods Enzymol 531:371–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Norman JM, Handley SA, Baldridge MT, Droit L, Liu CY, Keller BC, Kambal A, Monaco CL, Zhao G, Fleshner P, Stappenbeck TS, McGovern DP, Keshavarzian A, Mutlu EA, Sauk J, Gevers D, Xavier RJ, Wang D, Parkes M, Virgin HW. 2015. Disease-specific alterations in the enteric virome in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell 160:447–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yang T, Santisteban MM, Rodriguez V, Li E, Ahmari N, Carvajal JM, Zadeh M, Gong M, Qi Y, Zubcevic J, Sahay B, Pepine CJ, Raizada MK, Mohamadzadeh M. 2015. Gut dysbiosis is linked to hypertension. Hypertension 65:1331–1340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wei Y, Li Y, Yan L, Sun C, Miao Q, Wang Q, Xiao X, Lian M, Li B, Chen Y, Zhang J, Li Y, Huang B, Li Y, Cao Q, Fan Z, Chen X, Fang JY, Gershwin ME, Tang R, Ma X. 2020. Alterations of gut microbiome in autoimmune hepatitis. Gut 69:569–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Riva A, Borgo F, Lassandro C, Verduci E, Morace G, Borghi E, Berry D. 2017. Pediatric obesity is associated with an altered gut microbiota and discordant shifts in Firmicutes populations. Environ Microbiol 19:95–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schwiertz A, Taras D, Schafer K, Beijer S, Bos NA, Donus C, Hardt PD. 2010. Microbiota and SCFA in lean and overweight healthy subjects. Obesity (Silver Spring) 18:190–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brown CT, Davis-Richardson AG, Giongo A, Gano KA, Crabb DB, Mukherjee N, Casella G, Drew JC, Ilonen J, Knip M, Hyoty H, Veijola R, Simell T, Simell O, Neu J, Wasserfall CH, Schatz D, Atkinson MA, Triplett EW. 2011. Gut microbiome metagenomics analysis suggests a functional model for the development of autoimmunity for type 1 diabetes. PLoS One 6:e25792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sun Y, Chen Q, Lin P, Xu R, He D, Ji W, Bian Y, Shen Y, Li Q, Liu C, Dong K, Tang YW, Pei Z, Yang L, Lu H, Guo X, Xiao L. 2019. Characteristics of gut microbiota in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Shanghai, China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 9:369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sherid M, Samo S, Sulaiman S, Husein H, Sifuentes H, Sridhar S. 2016. Liver abscess and bacteremia caused by lactobacillus: role of probiotics? Case report and review of the literature. BMC Gastroenterol 16:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Miettinen M, Lehtonen A, Julkunen I, Matikainen S. 2000. Lactobacilli and Streptococci activate NF-kappa B and STAT signaling pathways in human macrophages. J Immunol 164:3733–3740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Duncan SH, Louis P, Flint HJ. 2004. Lactate-utilizing bacteria, isolated from human feces, that produce butyrate as a major fermentation product. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:5810–5817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Venkataraman A, Sieber JR, Schmidt AW, Waldron C, Theis KR, Schmidt TM. 2016. Variable responses of human microbiomes to dietary supplementation with resistant starch. Microbiome 4:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jenq RR, Taur Y, Devlin SM, Ponce DM, Goldberg JD, Ahr KF, Littmann ER, Ling L, Gobourne AC, Miller LC, Docampo MD, Peled JU, Arpaia N, Cross JR, Peets TK, Lumish MA, Shono Y, Dudakov JA, Poeck H, Hanash AM, Barker JN, Perales MA, Giralt SA, Pamer EG, van den Brink MR. 2015. Intestinal blautia is associated with reduced death from graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21:1373–1383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Maji A, Misra R, Dhakan DB, Gupta V, Mahato NK, Saxena R, Mittal P, Thukral N, Sharma E, Singh A, Virmani R, Gaur M, Singh H, Hasija Y, Arora G, Agrawal A, Chaudhry A, Khurana JP, Sharma VK, Lal R, Singh Y. 2018. Gut microbiome contributes to impairment of immunity in pulmonary tuberculosis patients by alteration of butyrate and propionate producers. Environ Microbiol 20:402–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Velázquez KT, Enos RT, Bader JE, Sougiannis AT, Carson MS, Chatzistamou I, Carson JA, Nagarkatti PS, Nagarkatti M, Murphy EA. 2019. Prolonged high-fat-diet feeding promotes non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and alters gut microbiota in mice. World J Hepatol 11:619–637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Da Silva HE, Teterina A, Comelli EM, Taibi A, Arendt BM, Fischer SE, Lou W, Allard JP. 2018. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with dysbiosis independent of body mass index and insulin resistance. Sci Rep 8:1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ma HY, Xu J, Liu X, Zhu Y, Gao B, Karin M, Tsukamoto H, Jeste DV, Grant I, Roberts AJ, Contet C, Geoffroy C, Zheng B, Brenner D, Kisseleva T. 2016. The role of IL-17 signaling in regulation of the liver-brain axis and intestinal permeability in Alcoholic Liver Disease. Curr Pathobiol Rep 4:27–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Astbury S, Atallah E, Vijay A, Aithal GP, Grove JI, Valdes AM. 2020. Lower gut microbiome diversity and higher abundance of proinflammatory genus Collinsella are associated with biopsy-proven nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gut Microbes 11:569–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhang L, Ouyang Y, Li H, Shen L, Ni Y, Fang Q, Wu G, Qian L, Xiao Y, Zhang J, Yin P, Panagiotou G, Xu G, Ye J, Jia W. 2019. Metabolic phenotypes and the gut microbiota in response to dietary resistant starch type 2 in normal-weight subjects: a randomized crossover trial. Sci Rep 9:4736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wu XK, Ma CF, Yu PB, Wang XL, Han L, Li MX, Xu JR. 2015. Significance of the quantitative analysis of Lactobacillus and Peptostreptococcus productus of gut microbiota in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Xi'an Jiaotong Univ (Med Sci) 36:93–97, 134. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Byndloss MX, Olsan EE, Rivera-Chavez F, Tiffany CR, Cevallos SA, Lokken KL, Torres TP, Byndloss AJ, Faber F, Gao Y, Litvak Y, Lopez CA, Xu G, Napoli E, Giulivi C, Tsolis RM, Revzin A, Lebrilla CB, Baumler AJ. 2017. Microbiota-activated PPAR-gamma signaling inhibits dysbiotic Enterobacteriaceae expansion. Science 357:570–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ferrari SM, Fallahi P, Vita R, Antonelli A, Benvenga S. 2015. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor- gamma in thyroid autoimmunity. PPAR Res 2015:232818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Burcelin R, Serino M, Chabo C, Blasco-Baque V, Amar J. 2011. Gut microbiota and diabetes: from pathogenesis to therapeutic perspective. Acta Diabetol 48:257–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]