Abstract

Background: Mutations of the thyroid hormone (TH)-specific cell membrane transporter, monocarboxylate transporter 8 (MCT8), produce an X-chromosome-linked syndrome of TH deficiency in the brain and excess in peripheral tissues. The clinical consequences include brain hypothyroidism causing severe psychoneuromotor abnormalities (no speech, truncal hypotonia, and spastic quadriplegia) and hypermetabolism (poor weight gain, tachycardia, and increased metabolism, associated with high serum levels of the active TH, T3). Treatment in infancy and childhood with TH analogues that reduce serum triiodothyronine (T3) corrects hypermetabolism, but has no effect on the psychoneuromotor deficits. Studies of brain from a 30-week-old MCT8-deficient embryo indicated that brain abnormalities were already present during fetal life.

Methods: A carrier woman with an affected male child (MCT8 A252fs268*), pregnant with a second affected male embryo, elected to carry the pregnancy to term. We treated the fetus with weekly 500 μg intra-amniotic instillation of levothyroxine (LT4) from 18 weeks of gestation until birth at 35 weeks. Thyroxine (T4), T3, and thyrotropin (TSH) were measured in the amniotic fluid and maternal serum. Treatment after birth was continued with LT4 and propylthiouracil. Follow-up included brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and neurodevelopmental evaluation, both compared with the untreated brother.

Results: During intrauterine life, T4 and T3 in the amniotic fluid were maintained above threefold to twofold the baseline and TSH was suppressed by 80%, while maternal serum levels remained unchanged. At birth, the infant serum T4 was 14.5 μg/dL and TSH <0.01 mU/L compared with the average in untreated MCT8-deficient infants of 5.1 μg/ and >8 mU/L, respectively. MRI at six months of age showed near-normal brain myelination compared with much reduced in the untreated brother. Neurodevelopmental assessment showed developmental quotients in receptive language and problem-solving, and gross motor and fine motor function ranged from 12 to 25 at 31 months in the treated boy and from 1 to 7 at 58 months in the untreated brother.

Conclusions: This is the first demonstration that prenatal treatment improved the neuromotor and neurocognitive function in MCT8 deficiency. Earlier treatment with TH analogues that concentrate in the fetus when given to the mother may further rescue the phenotype.

Keywords: MCT8, Allan–Herndon–Dudley syndrome, TH membrane transporter, prenatal treatment, amniotic fluid, genetics, hypothyroidism, thyroid hormone action

Introduction

The Monocarboxylate transporter 8 (MCT8; SLC16A2) gene located on the X chromosome encodes a cell membrane protein that specifically transports thyroid hormone (TH). Mutations in the MCT8 gene cause an X-linked intellectual disability syndrome known as the Allan–Herndon–Dudley syndrome with characteristic abnormalities in serum thyroid function tests and tissue-specific TH excess and deficiency (1,2). The discrepant TH deficiency in the brain and excess in peripheral tissues, expressing alternative TH transporters, manifest in affected males with severe psychoneuromotor abnormalities (early poor head control and truncal hypotonia, followed by inability to stand or walk, no speech, abnormal involuntary movements, and spasticity) and hypermetabolism (failure to thrive, tachycardia) (3,4). Thyroid test abnormalities are characteristic and include high serum concentrations of triiodothyronine (T3), low reverse T3 (rT3), and borderline low thyroxine (T4), while thyrotropin (TSH) is normal or slightly elevated (3,4). Treatment with physiological doses of levothyroxine (LT4) has been ineffective and supraphysiologic doses aggravated the T3-toxicosis (5).

Three therapeutic modalities have been applied in infancy and childhood, which controlled, to a variable degree, the hypermetabolism but had no significant effect on the psychoneuromotor abnormalities. Two are TH analogues that, in mouse studies, showed to enter cells bypassing the MCT8, diiodothyropropionic acid (DITPA) (6), and triiodothyroacetic acid (TRIAC) (7). DITPA given to patients for 26 to 40 months starting at 8.5 to 25 months of age corrected all thyroid test abnormalities (8) and TRIAC given for 13 months in infants as young as 10 months and in adults normalized serum T3, and also further reduced T4 and decreased TSH (9). Both TH analogues reduced hypermetabolism, producing weight gain, but had no significant effect on the psychoneuromotor deficit. Treatment with a combination of LT4 and propylthiouracil (PTU) increased serum T4 while reducing the T3 concentration, but also showed no objective improvement in the psychoneuromotor defect. Results of these three treatments are reviewed and summarized by Groeneweg et al. (3).

Data from an MCT8-deficient aborted fetus (10) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in infancy (11,12) demonstrate brain abnormalities with impaired myelination, suggesting that defective brain development is already present in fetal life.

We describe herein the effect of treating an MCT8-deficient fetus with weekly intra-amniotic instillations of LT4. This treatment was used rather than a TH analogue, because at the time of the study we did not have yet the Food and Drug Administration approval for the use of a TH analogue that crosses the placenta and is concentrated in the fetus (13). Although the absence of MCT8 impairs the entry of TH into the brain, both T4 and T3 have been measured in the brain of an MCT8-deficient human fetus, although in reduced amounts (10). This is probably mediated through an alternative transporter, namely, OATP1C1, shown to be present in the human fetal brain (14). Thus, it was logical to assume that increasing the blood concentration in T4 will further increase the amount of TH available to the brain. T4 was the preferred TH for two reasons: first, T3 from the fetal blood does not accumulate in the brain but is locally generated from T4 (15); and second, intra-amniotic T4 and not T3 has been used in the treatment of fetal goiter (16).

In the current study, neurodevelopmental data obtained from the child treated in-utero were compared with those obtained from his untreated older brother expressing the same MCT8 gene defect but receiving similar treatment and care postnatally. This first prenatal treatment of MCT8 deficiency provides compelling evidence that future attempts at successful treatment will require early prenatal intervention.

Methods

Patient and treatment

A heterozygous mother harboring on one of her X-chromosomes the MCT8 (long version) mutation c.754delG p.A252fs268* producing a truncated protein, and having given birth to a boy carrying the same mutation (see Supplementary Data and Fig. 1), was pregnant with another male fetus. Prenatal diagnosis indicated that the fetus harbored the MCT8 gene mutation (Supplementary Fig. S1). Genotyping was confirmed by the University of Chicago Genetic Service Laboratory, which is CLIA-certified and CAP-accredited. As the parents decided not to terminate the pregnancy, and knowing the devastating effect of the mutation on the fetus, a decision was made to treat the fetus using intra-amniotic LT4. Treatment was initiated at 18 weeks of gestation with 500 μg LT4 instilled every week until spontaneous vaginal delivery at 35 weeks due to preterm premature rupture of membrane. The dose and weekly treatment were based on previous experience with intra-amniotic administration of LT4 for fetal goiter (16). Before each LT4 instillation, a sample of amniotic fluid was collected to determine the concentrations of iodothyronines and TSH. Blood was also obtained from the mother at intervals for similar measurements. Fetal heart rate and intrauterine growth were also measured.

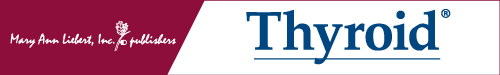

FIG. 1.

Measurements carried out in amniotic fluid, fetus, and mother during intra-amniotic LT4 treatment as well as in infancy and early childhood. (A) T4, T3, rT3, and TSH in amniotic fluid. Samples were obtained at baseline and just before the instillation of 500 μg of LT4 each week, starting at week 18. (B) Concentrations of the same substances in maternal serum. (C) Fetal heart rate and growth as estimated weight. (D) Serum free T4 and T3 postnatally, during infancy, and childhood. The infant was treated with LT4 and PTU, as described in the Methods section, with the goal of maintaining serum T4 above (green arrow) and T3 below (red arrow) the upper limit of normal (dashed line) for age. LT4, levothyroxine; PTU, propylthiouracil; rT3, reverse T3; T3, triiodothyronine; T4, thyroxine; TSH, thyrotropin.

Following spontaneous preterm delivery at 35 weeks, treatment of the newborn with LT4 and PTU was initiated on day 7 of postnatal life. The aim of the treatment was to provide T4, which would more readily be available to the brain by allowing it to reach serum concentrations above the upper limit of normal while reducing the T3 concentrations below the upper limit of normal, thus mitigating its hypermetabolic effect on peripheral tissues and the failure to thrive (3). PTU but not methimazole blocks deiodinase type-1 that generates the active TH, T3, from T4 in peripheral tissues. However, the generation of T3 from T4 in the brain is not affected by PTU, as it does not block deiodinase type-2, the predominant deiodinase expressed in the brain (17). LT4 was given orally once daily and PTU orally three times a day, as required to maintain its effect on blocking deiodinase type-1. Because of the potential adverse effects of PTU, liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase and alanine transaminase), white blood cells, and neutrophils were measured first at monthly intervals, then every two to four months and with adjustment of the PTU dose, The postnatal treatment produced no side effects or abnormalities in the abovementioned tests. Unfortunately, the schedule was not strictly adhered to as several doses were missed.

The manifestations and evolution of MCT8 deficiency are variable. While most individuals are severely affected and can never stand walk and speak, some can walk with shuffling gait and even develop garbled speech (18). The evolution of the syndrome depends on the nature of the mutation in terms of function (18,19), supporting therapy (such as physical, occupational, speech), nutrition, and home environment aided by parental and professional support (4). Thus, an ideal control for this prenatally diagnosed and treated boy would be his brother, an individual with the same mutation who received the same postnatal treatment and support, but not the prenatal treatment (see Supplementary Data).

Measurements

T4, total and free, total T3, and TSH in serum were measured by chemiluminescence immunometric assays using the Elecsys Automated System (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, GmbH and Hitachi, Ltd., Indianapolis, IN). With the exception of T3, the same platform was used for the measurements made in amniotic fluid. T3 was extracted from the amniotic fluid and measured by radioimmunoassay, established for the measurement of iodothyronine extracted from tissues. rT3 in serum and amniotic fluid was measured by radioimmunoassay (Adaltis Italia S'P'A, Bologna, Italy). High concentrations required dilution with the appropriate matrix devoid of the iodothyronine being measured. Accuracy for all iodothyronine measurements was confirmed by tandem mass spectrometry [see supplement to publication by Ferrara et al. (20)].

Fetal heart rate was measured by M-Mode ultrasound, and fetal weight estimated by ultrasonography.

Neurodevelopmental assessment

Both children are severely neurologically impaired. To assure reliable and reproducible evaluations in the treated child and his untreated brother, serving as control, neurodevelopmental assessments were completed by two neurodevelopmental disabilities specialists (P.A.B. and M.W.J.) utilizing motor milestone achievement reference tables (21,22) and the CAT/CLAMS neurocognitive assessment scale (21,23).

Results

Measurements of iodothyronines and TSH in amniotic fluid are shown in Figure 1A. One week following the first instillation of LT4 in the amniotic fluid (gestational week 18), T4 rose to 24 μg/dL, a 50-fold increase from the baseline level before treatment (gestational week 17). Similar increases were noted in T3 and greater in rT3 (140-fold). Concentrations of all iodothyronines declined with the increase in fetal size, but values remained above baseline until delivery. The observation that changes in T3 paralleled those of T4 indicates that despite the important conversion of T4 to rT3, a significant amount of the active hormone, T3, was generated. Its biological effect is supported by the decline in TSH. Maternal serum thyroid function tests remained unchanged throughout the period of fetal treatment, indicating that no significant amount of the LT4 administered and iodothyronines generated in the amniotic fluid reached the maternal circulation (Fig. 1B). Fetal heart rates and growth remained within the range of normal for gestational age (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, during the serial ultrasound examinations, no structural fetal anomalies were noted. Specifically, no evidence of fetal tachycardia or hydrops was noted.

The infant had an uncomplicated delivery at 35 weeks: weight, 2990 g; length, 49.5 cm; head circumference, 33 cm; and Apgar score 8 at 1 minute and 9 at 5 minutes. Thyroid tests on day 3 of life were as follows: T4 of 16.7 μg/dL compared with reference range of 6–15 μg/dL and mean ± standard deviation value in MCT8 deficiency of 5.1 ± 1.6 (N = 8); range 3.1 = 8.4 μg/dL. TSH was <0.005 mU/L compared with reference range of 2.3–9.7 mU/L and >8 mU/L (N = 23) in MCT8 deficiency [reference range from Lem et al. (24) and data for MCT8 deficiency from (Personal-Observation)]. T3 was 112 ng/dL and rT3 was 640 ng/dL, both in the reference range for age. His untreated brother's T4 and TSH at the same age were 4.0 μg/dL and 10.5 mU/L, respectively.

Treatment with LT4 and PTU was initiated at seven days of age and results are shown in Figure 1D. The goal was to maintain free T4 levels above the upper limit of normal and T3 levels below the upper limit of normal. This was only temporarily achieved for T4 but not for T3, owing to issues with adherence to the recommended treatment regimen (Fig. 1D).

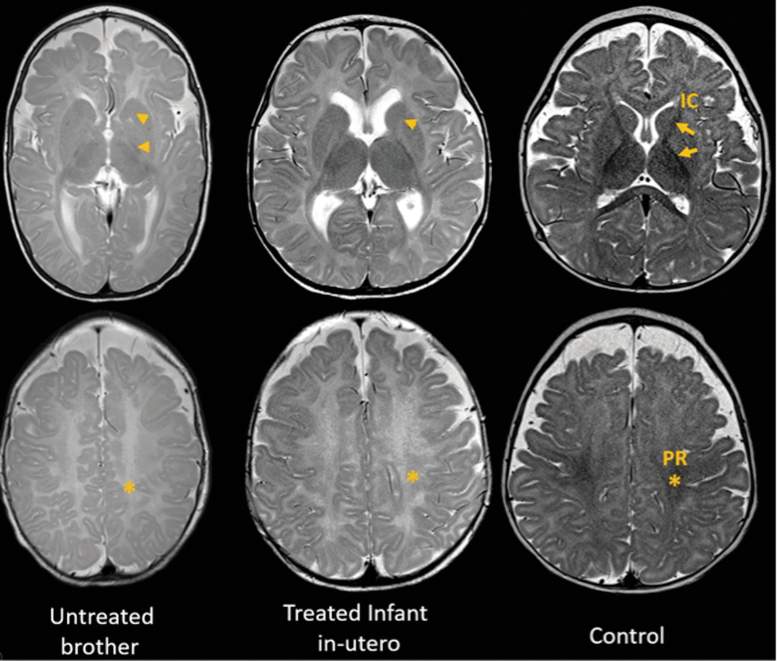

Brain MRI was obtained at 7 months of chronological age (representing 6 months of corrected age when adjusted for delivery at 35 weeks) and compared with that of his untreated brother and a normal control at 6 months (both born at term). Images were read blindly by one of us (M.G.M.), and T2-weighted images are shown in Figure 2. Compared with the control, the treated infant showed mildly delayed myelination in the anterior limb of the internal capsule, anterior aspect of the corpus callosum and perirolandic area, while myelination of the cerebellar peduncles appeared normal. This degree of reduced myelination is sometimes seen in normal infants. In contrast, his untreated brother showed more significantly delayed myelination in the same brain areas and it was also present in the cerebellar peduncles. The abnormal head shape, seen in the untreated brother, suggested severe hypotonia causing him to rest on the temporal side of his head, known as positional plagiocephaly.

FIG. 2.

T2-weighted images of magnetic resonance imaging obtained at six months of age (adjusted for prematurity) from the untreated brother (left), treated infant (center), and a normal male control (right). Control images illustrate the expected myelination pattern with arrows marking the IC and an asterisk marking the PR. When compared with control, the treated infant showed mildly delayed myelination in the anterior limb of the IC (arrowhead) and PR (asterisk). This degree of reduced myelination is sometimes seen in normal infants. In contrast, the infant's untreated brother, harboring the same MCT8 gene mutation, showed significantly delayed myelination that was more evident in the PR (asterisk) and posterior and anterior IC (arrowheads). The abnormal head shape suggested severe hypotonia producing elongation of the calvarium (dolichocephaly), which may be caused by difficulty moving his head and persistently lying on the temporal side of the head. IC, internal capsule; MCT8, monocarboxylate transporter 8; PR, perirolandic area.

When the child and his brother were seen for in-depth neurodevelopmental assessments at ages 31 and 58 months, respectively, the brothers were very neurologically affected in almost identical ways and both were severely impaired developmentally. The striking difference was the degree of abnormality (Tables 1 and 2). At no time did the older untreated sibling ever demonstrate any of the higher functional capacities seen in the younger boy. Some differences were also observed in earlier examinations of the untreated brother, such as no effective reaching and grasp, spasticity present already at 10 months, and absence of head control throughout life (see Supplementary Data), while the prenatally treated brother could hold his head up at 2 months of age (Supplementary Fig. S2A).

Table 1.

Developmental Evaluation

| Chronologic age, months | Treated sibling |

Untreated sibling |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31 | 58 | |||

| Functional level | Months equivalent | Developmental quotienta | Months equivalent | Developmental quotienta |

| Test item | ||||

| Receptive language | 25 | 7.6 | 7 | 4.3 |

| Visuomotor/problem-solving | 23 | 7.2 | 3 | 1.9 |

| Gross motor milestones | 12 | 4 | UC | <1 |

| Fine motor milestones | 19 | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| Head held up in prone | Yes | No | ||

| Head control on pull to sit | Excellent | None | ||

| Rolling, supine to prone, and vice versa | Yes | No | ||

| Propped sitting | Partially maintains | Not at all | ||

| Bears weight in supported standing | Yes | No | ||

| Reaches accurately for objects | Yes | No | ||

| Transfers hand to hand | Yes | No | ||

| Matches picture to object | Yes | No | ||

| Holds spoon and brings it to mouth | Partially | No | ||

| Eye contact | Good | Poor to absent | ||

Expressed as functional developmental age divided by chronological age.

UC, unable to calculate.

Table 2.

Neurologic Examination (Distinguishing Features)

| Chronologic age, months | Treated sibling |

Untreated sibling |

|---|---|---|

| 31 | 58 | |

| Examination feature | ||

| Head—righting in supported sitting | Excellent | None |

| Muscle tone—extremities | Increased | Much increased spasticity |

| Movement disorder | Mildly dyskinetic | Marked dyskinesia choreoathetotic (almost ballistic) |

| Strength | Fair to good | Marked weakness |

| Hand use | Able to open, reach, and grasp | Fisted |

| Protective reactions | Present anteriorly but ineffective | Completely absent |

| Deep tendon reflexes | ||

| Upper extremity | 3+ to 4+ | 3+ to 4+ |

| Knee and ankle | 2+ and 2+ | 4+ and 2+ |

| Plantar | Withdrawal | extensor |

| Clonus | No | No |

Discussion

Herein we report the first prenatal treatment of MCT8 deficiency, a condition with characteristic thyroid test abnormalities and a severe neuropsychomotor defect. Treatment was undertaken at this early time in life for the following reasons: (i) brain abnormalities in MCT8 deficiency are already present before birth (10); (ii) postnatal treatment with TH analogues or combined T4 and PTU do not correct the neuropsychomotor defect (5,8,9,25) (Personal-Observation); and (iii) the parents elected to continue the pregnancy despite the poor outcome of a previously born child harboring the same MCT8 gene defect. The choice of LT4 as a treatment agent as well as the dose was based on the review of 22 publications on amniotic instillation of LT4 for the treatment of fetal goiter and in particular that of Ribault et al., reporting their experience in 12 pregnant women (16). Furthermore, TH analogues have not been approved in the United States for use in humans and LT4 crosses the blood/brain barrier more effectively to generate T3 locally in the brain (15,26). When given in supraphysiologic doses to Mct8-deficient mice, LT4 is more effective than administered T3 in producing a TH response (6).

The intra-amniotic administration of large doses of LT4 reached the fetal tissues and exerted a biological effect without altering the maternal thyroid function. Evidence for TH action in the fetus is provided by the generation of T3 and suppression of fetal TSH measured in the amniotic fluid. Furthermore, at birth, serum T4 was high and TSH suppressed, in contrast to untreated MCT8-deficient newborns. Evidence that prenatal TH deficiency has lasting effects on the fetus is supported by the finding that in regions of endemic iodine deficiency, cretinism with psychomotor deficits, similar to those observed in MCT8 deficiency, occurs when mothers are hypothyroid during early gestation (27).

In comparison with the untreated brother, neurodevelopmental evaluation results lend credence that the treatment had a beneficial effect on the child, although it did not fully correct the defect. The possibility that the older boy might have been on par with his brother at the same age of 31 months and had significantly deteriorated over time was excluded based on review of examinations done at earlier ages. Several factors could be brought as reasons for the partial rescue. (i) Treatment was not started early enough. Indeed the TH receptors appear in the human brain at week 10 of embryonic life and reach peak concentration at 16 weeks (28). (ii) The dose and site of administration of LT4 did not reach all areas of the brain. (iii) Postnatal treatment was inadequate.

It is clear that improvement of brain myelin deficiency, a known consequence of hypothyroidism (29), was not sufficient to fully rescue the neurodevelopmental deficit. This indicates that other abnormalities caused by lack of TH play a major role in the failure to achieve normal brain function. Thus, future initiation of prenatal treatment at the time of appearance of TH receptors in the brain will require a TH analogue that can be administered to the mother at 10 weeks of gestation, given that drug delivery into the amniotic fluid is not feasible at this time, as amniocentesis before 15 weeks is associated with limb reduction defects. The desired TH analogue will have to cross the placenta and concentrate in fetal tissues. Such a TH analogue, DITPA, has been used in pregnant dams carrying Mct8-deficient fetuses (13). A study to evaluate its utility in treating male fetuses harboring a defective MCT8 by oral administration of DITPA to a woman starting early in pregnancy has recently been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (30).

Supplementary Material

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, USA, DK15070 to Samuel Refetoff and DK110322 to Alexandra M. Dumitrescu, and by funds from the Esformes Thyroid Research Fund to Roy E. Weiss.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Dumitrescu AM, Liao XH, Best TB, Brockmann K, Refetoff S. 2004. A Novel syndrome combining thyroid and neurological abnormalities is associated with mutations in a monocarboxylate transporter gene. Am J Hum Genet 74:168–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Friesema EC, Grueters A, Biebermann H, Krude H, von Moers A, Reeser M, Barrett TG, Mancilla EE, Svensson J, Kester MH, Kuiper GG, Balkassmi S, Uitterlinden AG, Koehrle J, Rodien P, Halestrap AP, Visser TJ. 2004. Association between mutations in a thyroid hormone transporter and severe X-linked psychomotor retardation. Lancet 364:1435–1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Groeneweg S, van Geest FS, Peeters RP, Heuer H, Visser WE. 2020. Thyroid hormone transporters. Endocr Rev 41:bnz008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fu J, Refetoff S, Dumitrescu AM. 2013. Inherited defects of thyroid hormone-cell-membrane transport: review of recent findings. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 20:434–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Biebermann H, Ambrugger P, Tarnow P, von Moers A, Schweizer U, Grueters A. 2005. Extended clinical phenotype, endocrine investigations and functional studies of a loss-of-function mutation A150V in the thyroid hormone specific transporter MCT8. Eur J Endocrinol 153:359–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Di Cosmo C, Liao XH, Dumitrescu AM, Weiss RE, Refetoff S. 2009. A thyroid hormone analogue with reduced dependence on the monocarboxylate transporter 8 (MCT8) for tissue transport. Endocrinology 150:4450–4458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kersseboom S, Horn S, Visser WE, Chen J, Friesema EC, Vaurs-Barriere C, Peeters RP, Heuer H, Visser TJ. 2014. In vitro and mouse studies supporting therapeutic utility of triiodothyroacetic acid in MCT8 deficiency. Mol Endocrinol 28:1961–1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Verge CF, Konrad D, Cohen M, Di Cosmo C, Dumitrescu AM, Marcinkowski T, Hameed S, Hamilton J, Weiss RE, Refetoff S. 2012. Diiodothyropropionic acid (DITPA) in the treatment of MCT8 deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:4515–4523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Groeneweg S, Peeters RP, Moran C, Stoupa A, Auriol F, Tonduti D, Dica A, Paone L, Rozenkova K, Malikova J, van der Walt A, de Coo IFM, McGowan A, Lyons G, Aarsen FK, Barca D, van Beynum IM, van der Knoop MM, Jansen J, Manshande M, Lunsing RJ, Nowak S, den Uil CA, Zillikens MC, Visser FE, Vrijmoeth P, de Wit MCY, Wolf NI, Zandstra A, Ambegaonkar G, Singh Y, de Rijke YB, Medici M, Bertini ES, Depoorter S, Lebl J, Cappa M, De Meirleir L, Krude H, Craiu D, Zibordi F, Oliver Petit I, Polak M, Chatterjee K, Visser TJ, Visser WE. 2019. Effectiveness and safety of the tri-iodothyronine analogue TRIAC in children and adults with MCT8 deficiency: an international, single-arm, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 7:695–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lopez-Espindola D, Morales-Bastos C, Grijota-Martinez C, Liao XH, Lev D, Sugo E, Verge CF, Refetoff S, Bernal J, Guadano-Ferraz A. 2014. Mutations of the thyroid hormone transporter MCT8 cause prenatal brain damage and persistent hypomyelination. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99:E2799–E2804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gika AD, Siddiqui A, Hulse AJ, Edwards S, Fallon P, McEntagart ME, Jan W, Josifova D, Lerman-Sagie T, Drummond J, Thompson E, Refetoff S, Bönnemann CG, Jungbluth H. 2010. White matter abnormalities and dystonic motor disorder associated with mutations in the SLC16A2 gene. Dev Med Child Neurol 52:475–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Matheus MG, Lehman RK, Bonilha L, Holden KR. 2015. Redefining the pediatric phenotype of X-linked monocarboxylate transporter 8 (MCT8) deficiency: implications for diagnosis and therapies. J Child Neurol 30:1664–1668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ferrara AM, Liao XH, Gil-Ibanez P, Bernal J, Weiss RE, Dumitrescu AM, Refetoff S. 2014. Placenta passage of the thyroid hormone analog DITPA to male wild-type and Mct8-deficient mice. Endocrinology 155:4088–4093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lopez-Espindola D, Garcia-Aldea A, Gomez de la Riva I, Rodriguez-Garcia AM, Salvatore D, Visser TJ, Bernal J, Guadano-Ferraz A. 2019. Thyroid hormone availability in the human fetal brain: novel entry pathways and role of radial glia. Brain Struct Funct 224:2103–2119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Calvo R, Obregon MJ, Ruiz de Ona C, Escobar del Rey F, Morreale de Escobar G. 1990. Congenital hypothyroidism, as studied in rats. Crucial role of maternal thyroxine but not of 3,5,3'-triiodothyronine in the protection of the fetal brain. J Clin Invest 86:889–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ribault V, Castanet M, Bertrand AM, Guibourdenche J, Vuillard E, Luton D, Polak M, French Fetal Goiter Study G. 2009. Experience with intraamniotic thyroxine treatment in nonimmune fetal goitrous hypothyroidism in 12 cases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:3731–3739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bianco AC, Kim BW. 2006. Deiodinases: implications of the local control of thyroid hormone action. J Clin Invest 116:2571–2579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schwartz CE, May MM, Carpenter NJ, Rogers RC, Martin J, Bialer MG, Ward J, Sanabria J, Marsa S, Lewis JA, Echeverri R, Lubs HA, Voeller K, Simensen RJ, Stevenson RE. 2005. Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome and the monocarboxylate transporter 8 (MCT8) gene. Am J Hum Genet 77:41–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Visser WE, Jansen J, Friesema EC, Kester MH, Mancilla E, Lundgren J, van der Knaap MS, Lunsing RJ, Brouwer OF, Visser TJ. 2009. Novel pathogenic mechanism suggested by ex vivo analysis of MCT8 (SLC16A2) mutations. Hum Mutat 30:29–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ferrara AM, Liao XH, Gil-Ibanez P, Marcinkowski T, Bernal J, Weiss RE, Dumitrescu AM, Refetoff S. 2013. Changes in thyroid status during perinatal development of MCT8-deficient male mice. Endocrinology 154:2533–2541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Johnson CP, Blasco PA. 1997. Infant growth and development. Pediatr Rev 18:224–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Capute AJ, Shapiro BK, Palmer FB, Ross A, Wachtel RC. 1985. Normal gross motor development: the influences of race, sex and socio-economic status. Dev Med Child Neurol 27:635–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Visintainer PF, Leppert M, Bennett A, Accardo PJ. 2004. Standardization of the Capute Scales: methods and results. J Child Neurol 19:967–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lem AJ, de Rijke YB, van Toor H, de Ridder MA, Visser TJ, Hokken-Koelega AC. 2012. Serum thyroid hormone levels in healthy children from birth to adulthood and in short children born small for gestational age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:3170–3178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wemeau JL, Pigeyre M, Proust-Lemoine E, d'Herbomez M, Gottrand F, Jansen J, Visser TJ, Ladsous M. 2008. Beneficial effects of propylthiouracil plus L-thyroxine treatment in a patient with a mutation in MCT8. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:2084–2088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kester MH, Martinez de Mena R, Obregon MJ, Marinkovic D, Howatson A, Visser TJ, Hume R, Morreale de Escobar G. 2004. Iodothyronine levels in the human developing brain: major regulatory roles of iodothyronine deiodinases in different areas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:3117–3128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boyages SC, Halpern JP. 1993. Endemic cretinism: toward a unifying hypothesis. Thyroid 3:59–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bernal J, Pekonen F. 1984. Ontogenesis of the nuclear 3,5,3'-triiodothyronine receptor in the human fetal brain. Endocrinology 114:677–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bernal J 2005. Thyroid hormones and brain development. Vitam Horm 71:95–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. ClinicalTrials.gov trial NCT04143295—Rescue of infants with MCT8 deficiency. Available at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04143295 (accessed September15, 2020)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.