Abstract

Molecular imaging studies have shown low cerebral concentration of serotonin transporter in patients suffering from depression, compared to healthy control subjects. Whether or not this difference also is present before disease onset and after remission (i.e. a trait), or only at the time of the depressive episode (i.e. a state) remains to be explored. We examined 17 patients with major depressive disorder with positron emission tomography using [11C]MADAM, a radioligand that binds to the serotonin transporter, before and after treatment with internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy. In all, 17 matched healthy control subjects were examined once. Cerebellum was used as reference to calculate the binding potential. Differences before and after treatment, as well as between patients and controls, were assessed in a composite cerebral region and in the median raphe nuclei. All image analyses and confirmatory statistical tests were preregistered. Depression severity decreased following treatment (p < 0.001). [11C]MADAM binding in patients increased in the composite region after treatment (p = 0.01), while no change was observed in the median raphe (p = 0.51). No significant difference between patients at baseline and healthy controls were observed in the composite region (p = 0.97) or the median raphe (p = 0.95). Our main finding was that patients suffering from a depressive episode show an overall increase in cerebral serotonin transporter availability as symptoms are alleviated. Our results suggest that previously reported cross-sectional molecular imaging findings of the serotonin transporter in depression most likely reflect the depressive state, rather than a permanent trait. The finding adds new information on the pathophysiology of major depressive disorder.

Subject terms: Depression, Molecular neuroscience

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is the leading cause of disability worldwide1, but the biological underpinnings of the disorder are still largely unknown. The monoamine hypothesis has been the dominant pathophysiological model for half a century2. Aberrations in the monoamine serotonin (5-HT) system is one of the most replicated observations in experimental MDD research3–5 and most efficacious pharmacological treatments target the serotonin system6,7. However, it is not known if serotonin plays a direct causal role in the pathophysiology of depression, as suggested by the classical interpretation of the monoamine hypothesis;5 or if change in 5-HT activity is part of a salutogenic response to stress, enhancing adaptive responses to adverse conditions8,9. Nor is it known if aberrations in the serotonin system are trait-like, or if they are temporary, only present during the time of the illness10,11. To answer these basic questions is of key importance for the development of better MDD treatment options.

The serotonin transporter (5-HTT) has received a lot of attention in MDD research, in part since it is the primary mechanism to decrease extracellular 5-HT12, but also because it is the target of the most commonly used antidepressant drugs13. Positron emission tomography (PET) have been used to study 5-HTT in depression. Results from individual studies differ, showing lower binding in cortical and subcortical regions14–17, but also higher binding18. A meta-analysis has shown reduced 5-HTT binding in the midbrain and amygdala19, indicating a general trend towards lower cerebral 5-HTT availability in patients suffering from MDD20.

The dorsal and median raphe nuclei, located in the brainstem, are the main sites for cell bodies of serotonergic neurons12 and has the highest concentration of 5-HTT in the brain21. While both nuclei project axons to a wide array of partially overlapping cerebral targets the pattern of projections differ22. The median raphe has been suggested to be of particular interest with regards to MDD23,24. The raphe nuclei are small structures that are not observable on a magnetic resonance image (MRI). This makes it challenging to examine with PET, especially using imaging systems with low spatial resolution. Results from meta-analyses of molecular imaging data suggest low 5-HTT availability also in raphe in MDD, but the interpretation is hampered by methodological drawbacks in the many different methods used for spatial definition.

In contrast to the relatively large number of cross-sectional (i.e., patient-control) PET-studies on MDD and 5-HTT there is a lack of studies examining the longitudinal course of 5-HTT availability in depression. It is thus unclear if the putative lower level of 5-HTT represent a “trait”, i.e., a risk factor for MDD chronically present, or a “state”, i.e., present only around the time of the depressive episode. Since most pharmacological treatment options against MDD affects the serotonergic system, it is difficult to interpret the results from pre-post molecular imaging studies using drugs to understand the natural progression of the disorder. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), on the other hand, has been shown to be as effective as pharmacological treatment of depression25. Internet delivered CBT (ICBT) has been found to be as effective as face-to-face CBT, and is available as an option in regular health care in many countries26,27. ICBT has standardized treatment modules, ensuring that all subjects get as close to the same intervention as possible and is thus a suitable intervention in a study of the longitudinal course of 5-HTT availability in MDD.

The primary aim of this study was to address the trait-state question of MDD biology by examining if the 5-HTT availability changes as subjects improve from a depressed state. The secondary aims were to compare the 5-HTT availability in the brain of depressed individuals with healthy controls; and to apply a novel approach to delineate the raphe nuclei and examine these regions separately using a high-resolution PET system.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee in Stockholm, Sweden, and the Radiation Safety Committee at Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm. All subjects gave verbal and written informed consent before participation.

In all, 17 patients with MDD and 17 healthy controls were included in the study. This sample size was decided on based on test–retest data for the applied radioligand28. All subjects were recruited by advertisement in local newspapers. Patients were assessed at the Internet Psychiatry clinic, which is part of the Region Stockholm University Health Care27. Diagnoses were given based on a full psychiatric assessment by a psychiatrist or a resident physician supervised by a psychiatrist, using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.)29. Post-treatment, the supervising psychiatrist assessed patients at a physical encounter. All subjects were healthy according to clinical interview, MRI of the brain, physical examination, and standard laboratory tests. Patients had an ongoing major depressive episode diagnosed using DSM-IV criteria30, with at least one prior episode of MDD. Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale31 (MADRS) was used to assess depression severity. Patients with a score above 18 and below 35 were eligible for inclusion. No ongoing psychopharmacological treatment of MDD was allowed. The subject with most recent exposure to antidepressant drug treatment had this discontinued 8 months prior to study inclusion.

The control subjects did not fulfill criteria for MDD, or any other diagnosis according to M.I.N.I., and had no history of psychiatric illness. Controls were matched to the patients for sex, age (±3 years) and intellectual ability (±1 standard deviation (SD) in the Matrix Reasoning subtest of WAIS-IV); (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demography and radioactivity data.

| Patients | Controls | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n | |||

| Female | 13 | 13 | – |

| Male | 4 | 4 | – |

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 47 ± 13 | 47 ± 14 | – |

| WAIS, matrix reasoningb (mean ± SD) | 12.4 ± 2.9 | 12.7 ± 3.2 | – |

| Current MDD episode duration, months | 15 ± 13 | – | – |

| Family history of MDD, n (%) | 7 (41%) | – | – |

| Prior MDD episodes, n (%) | |||

| 1–2 | 8 (47%) | – | – |

| >2 | 9 (53%) | – | – |

| Prior CBT, n (%) | 9 (53%) | – | – |

| Previous AD, n (%) | 9 (53%) | – | – |

| Time since AD, months (min–max) | 8–204 | – | – |

| Comorbid psychiatric diagnosisc, n (%) | 6 (35%) | – | – |

| Injected radioactivity, MBq (mean ± SD) | |||

| PET1 | 424 ± 82 | 408 ± 85 | 0.57 |

| PET2 | 406 ± 91 | – | 0.56 |

| Molar radioactivity, GBq/μmol (mean ± SD) | |||

| PET1 | 216 ± 65 | 231 ± 134 | 0.67 |

| PET2 | 200 ± 81 | – | 0.52 |

| Injected mass, μg (mean ± SD) | |||

| PET1 | 0.58 ± 0.19 | 0.93 ± 1.28 | 0.28 |

| PET2 | 0.68 ± 0.38 | – | 0.33 |

AD antidepressant, CBT Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, MDD major depressive disorder.

aCalculated using independent t test.

bRaw score standardized for age.

cGeneralized anxiety disorder; social anxiety disorder; panic disorder; hypochondriasis.

Study design

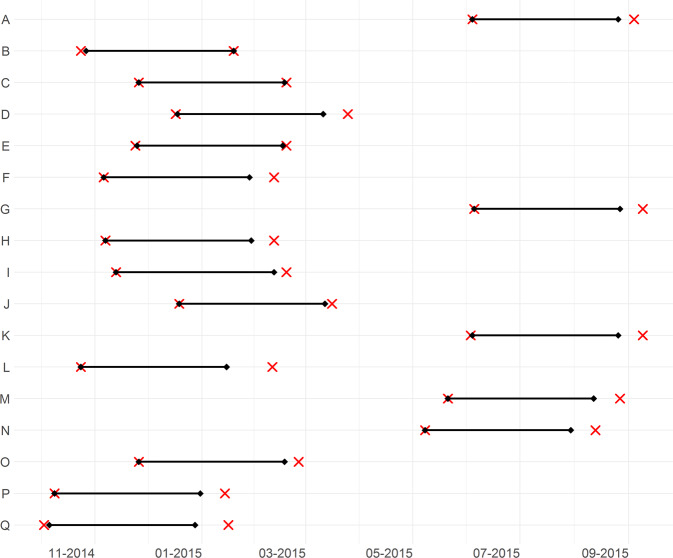

After the first PET examination (PET1) ICBT was initiated followed by a second PET examination (PET2) after treatment completion. Self rated MADRS32 (MADRS-S) was measured weekly. Clinical global rating scale Improvement (CGI-I) was assessed at follow up (details on rating scales in Supplement 1). The average treatment duration was 11 weeks and time between PET1 and PET2 was 12–16 weeks (Fig. 1). Controls were recruited separately; they did not receive any treatment and were examined once with PET.

Fig. 1. Timelines for study participation of all MDD patients.

Dates for initiation and completion of cognitive behavioral therapy (black diamonds connected with horizontal line), and PET1 and PET2 (red crosses). One row per patient, letters corresponding to Fig. 3A.

Cognitive behavioral therapy

The ICBT treatment protocol applied in this study has been tested in randomized studies33, and shown to be effective34. The main component of the treatment program is 10 text modules, covering specific themes such as psychoeducation, behavioral activation, cognitive restructuring, and relapse prevention. Each module ends with a homework assignment. Throughout the treatment, all participants are assigned a psychologist who supervises the progress and provides individual feedback.

MRI and PET experimental procedure

T1-weighted MRI images were acquired using a 3T GE Signa system (GE Medical Systems, Chicago, Illinois, USA). All subjects were examined using a high-resolution research tomograph (Siemens Molecular Imaging, USA) with a maximum spatial resolution of ~2 mm full-width-half-maximum35. Transmission scans were performed prior to each PET measurement to correct for signal attenuation.

[11C]MADAM, a radioligand suitable for quantification of the serotonin transporter, was synthesized as described previously36. In each PET-experiment a saline solution containing [11C]MADAM was injected into a antecubital vein as a bolus (<10 s). The cannula was then flushed with 10 mL saline. Injected radioactivity, molar radioactivity and injected mass are reported in Table 1. Emission data were acquired continuously for 93 min, and subsequently binned into 38 consecutive time frames using the following frame definitions: nine 10 s, two 15 s, three 20 s, four 30 s, four 1 min, four 3 min, and twelve 6 min frames.

Image preprocessing and quantification

Dynamic PET images were corrected for head motion using a between-frame-correction algorithm implemented in SPM12 (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, University College, London, UK) where frames were realigned to the first six-minute frame. Using SPM12 the T1-weighted MR-images were then co-registered to a time-weighted summated PET-image. To derive regional time-activity curves (TACs), the resulting co-registration matrix was used to project regions of interest (ROIs) on the realigned dynamic PET-image.

From the time-activity curves, binding potential with respect to non-displaceable uptake (BPND) was calculated for each ROI using the non-invasive Logan plot37 fitted with multilinear regression38, with t* = 45 min, corresponding to eight frames. The model requires the reference region efflux rate constant (k2′) as an input. This was set to the k2′ value from putamen39, derived using the simplified reference tissue model40, resulting in values between 0.04 and 0.11, in line with values derived using arterial input function37. Cerebellar gray matter was defined as described previously41 and used as reference region42.

Parametric images were generated using the 3D stationary wavelet aided parametric imaging (WAPI) procedure, where the non-invasive Logan plot, fitted with multilinear regression, is applied on TACs from individual voxels43,44. For visualizations, the parametric images were registered to MNI-space45 and averaged across individuals.

Regions of interest

FreeSurfer (version 6.0, http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/)46 was used to delineate brain regions on the T1-weighted MRIs. We tested two regions of interest: (i) median raphe nuclei, and (ii) a composite region consisting of anatomical structures where the [11C]MADAM signal-to-noise ratio was deemed acceptable: amygdala, anterior cingulate gyrus (ACC), posterior cingulate gyrus (PCC), caudate, hippocampus, insular cortex, putamen, and thalamus. The composite region was created using weighted standardization, with weights derived from the volume and variance in BPND for each of the included ROIs (see Supplement 1 for details).

The reasons for creating a composite ROI were: (i) 5-HT proteins examined with PET have shown high interregional correlations47, supporting the idea of a central regulation of the expression of serotonergic proteins from the raphe nuclei. By extension, a putative change in 5-HTT could be expected globally in the brain. (ii) Previous patient-control molecular imaging studies of 5-HTT in MDD have implicated several different brain regions14–17,48. (iii) Combining many small regions into one large increase the statistical power through reduction both of noise and the number of comparisons.

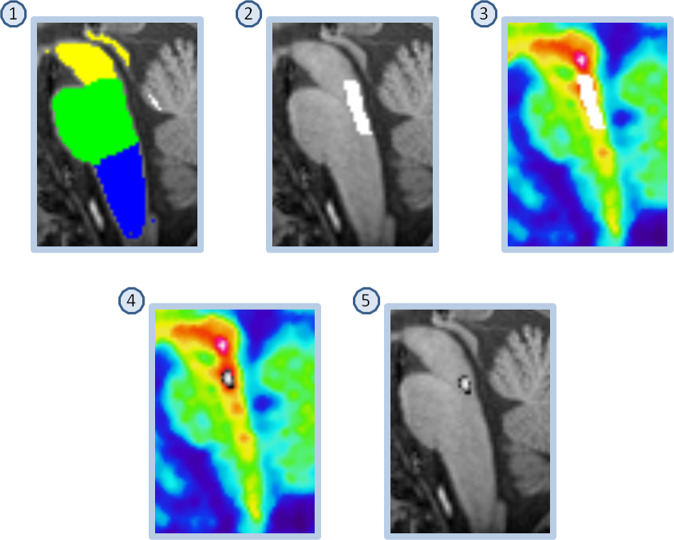

ROIs preferentially sampling the dorsal- and median raphe respectively were created using a version of a previously described semi-automatic method44,49, here fully automated (Fig. 2, see Supplement 1 for details). For each individual, the resulting masks were applied to the WAPI-images to calculate a BPND value.

Fig. 2. Delineation of region preferentially sampling median raphe.

(1) FreeSurfer Brainstem Substructures. (2) The pons mask (green) was trimmed, keeping the most dorsal 5 voxels. (3) The resulting mask was overlaid on the time-weighted summated PET-image. (4) Median raphe is the structure with highest [11C]MADAM binding within the boundaries of the trimmed pons mask; the most intense PET-voxel was located and in an iterative process the voxel with highest intensity adjacent to the initial voxel was added until 65 voxels were collected. (5) The resulting mask overlaid on the MR-image. The same procedure was used to delineate a region preferentially sampling dorsal raphe except for using the midbrain mask (yellow in panel 1) and 116 voxels.

Preregistration

Following recent recommendation for PET studies50, the image analysis and statistical plan was preregistered at AsPredicted.com (Supplement 2). The preregistration was submitted after collection of data was completed, but before any analysis of PET-data was performed. Deviations from the preregistration were as follows: (i) Slow radioligand kinetics were observed in pallidum in several controls and patients. A central assumption of the model used for quantification of [11C]MADAM binding is reversible kinetics of the radioligand. Since no clear peak of the time activity curve was observed in eight subjects, pallidum was removed from the composite region in the main analysis. (ii) In one patient the BPND values calculated in the second PET examination were unrealistically high (~4 standard deviations higher than the average). This subject was excluded from the longitudinal analysis, but the baseline examination was included in the cross-sectional analysis. In Supplement 1, we report results including this outlier and with pallidum included in the composite region, i.e., verbatim the preregistration (Supplement 1, Fig. S1 and S2; Table S1). All analyses that were part of the preregistration plan are presented as confirmatory. Analyses that were not part of the preregistration plan are presented as exploratory.

Statistics

Confirmatory analyses

Change in MADRS-S was assessed using a multilevel model for repeated measures. Subjects were fitted over time with varying intercepts and slopes. CGI-I data was tested against “4” (i.e., “no change”) using the Wilcoxon one-sample signed rank test.

Paired t-test was used to assess differences in BPND within patients before and after CBT, as well as between patients at baseline and their matched control subjects. For the cross-sectional analysis of the composite ROI, the preregistered prediction was that healthy control subjects should show higher BPND compared to patients, hence this test was one sided. All other tests were two sided. Alpha was set to 0.05 for all statistical tests.

In order to estimate the magnitude of difference between patients before and after treatment, and between patients and controls, the ratio of paired measurements was calculated for BPND of all ROIs that were part of the composite region. The median ratio was then calculated for each patient or patient-control pair. The average percentage difference between groups was reported.

Multiple comparisons

The longitudinal and cross-sectional analyses were considered separately. For both analyses two tests were performed: median raphe and the composite region. As per the preregistration, we examined the between-individual correlation between the difference score of the composite region and median raphe to decide if alpha correction was warranted. The correlation in the cross-sectional data was low (r = 0.25), indicating low dependence. For this reason, Bonferroni correction was applied. The correlation in the longitudinal analysis was high (r = 0.77), and no correction of alpha was made for this analysis.

Exploratory analysis

Paired two-tailed t-test was used for analysis of BPND values extracted from individual brain regions, both in the longitudinal and cross-sectional data.

To examine if change in MADRS-S was associated to change in [11C]MADAM BPND between PET1 and PET2, we extracted the maximum likelihood estimates of the subject specific slopes from the MADRS-S multilevel model. These were then entered as an independent variable into a regression model, predicting BPND from PET2 while controlling for BPND from PET1. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated to examine if baseline BPND was associated with baseline MADRS-S score.

Effect sizes were quantified using Cohen’s dz, a paired version of the classical Cohen’s d where the standard deviation of the difference score is used as denominator51.

Results

Confirmatory analysis

Longitudinal data

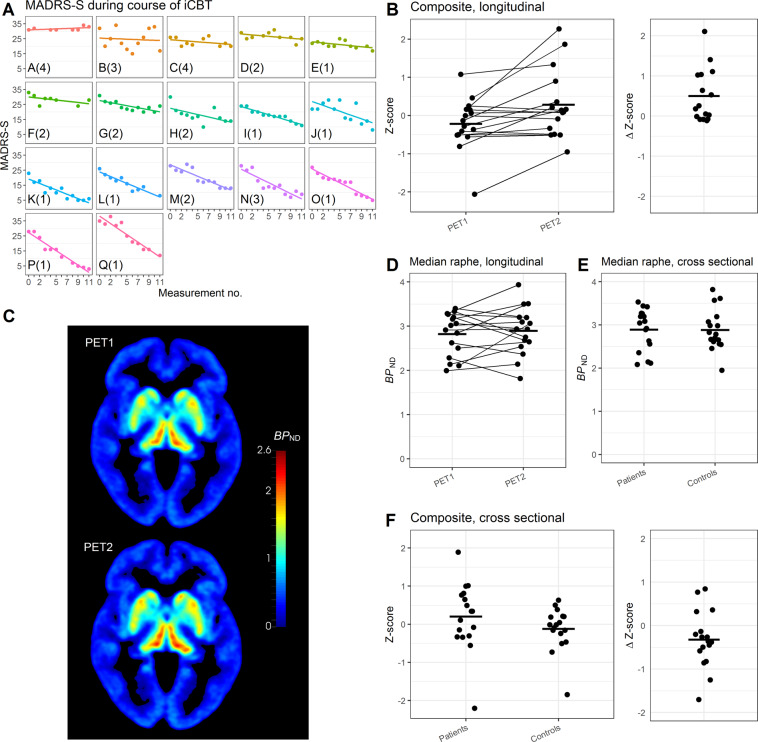

MADRS-S decreased, from 27.9 ± 3.8 (mean ± SD) at start of the ICBT treatment, to 14.9 ± 8.6 at completion (p < 0.001; Fig. 3A). The CGI-I data showed that 13 of 17 patients were classified as either “much” or “very much” improved. The test against “no change” was significant (p < 0.001), supporting an improvement in symptoms.

Fig. 3. MADRS-S and PET data.

In A MADRS-S measurements during the course of ICBT. Each cell represents one patient, (n = 17), letters in lower left corner corresponds to the letters in Fig. 1, numbers in parenthesis is CGI-I. In B longitudinal [11C]MADAM data (n = 16) for the composite region, PET1 (baseline) and PET2 (after treatment). Right panel shows difference scores between scans. In C mean parametric image of patients at baseline (upper image) and after treatment (lower image; n = 16), see Supplement 3 for a 3D movie of the same data. In D longitudinal data, median raphe, BPND at PET1 (baseline, left) and PET2 (after treatment, right). In E cross-sectional data, median raphe, BPND for patients with MDD at baseline (left) and healthy controls (right). In F cross-sectional [11C]MADAM data (n = 17 + 17) for the composite region, comparing patients with MDD at baseline to matched healthy controls. Right panel shows difference scores between matched pairs.

BPND increased on average 10% in the composite region following ICBT; PET 1 Mean Z-score = −0.22 ± 0.68, PET2 Mean Z-score = 0.28 ± 0.89, t(15) = −3.01, p = 0.01, 95% CI [−0.85, −0.15], Dz = 0.75. Binding in median raphe showed no change following treatment; PET 1 Mean BPND = 2.81 ± 0.48, PET2 Mean BPND = 2.89 ± 0.53, t(15) = −0.67, p = 0.51, 95% CI [−0.31, 0.16], Dz = 0.17 (Fig. 3B–D, Supplement 3 for a 3D movie).

Cross-sectional data

There was no evident difference in BPND between patients at baseline and healthy controls. [11C]MADAM binding in the composite region was on average 4% lower in controls compared to patients. The average Z-score for the composite region was −0.12 ± 0.57 for controls and 0.2 ± 0.89 for patients, providing no evidence for a difference between the groups, t(16) = −2.03, p = 0.97 (one sided), 95% CI [−0.60, Inf], Dz = 0.4 (Fig. 3C). For the median raphe, the average BPND was 2.88 ± 0.47 for controls and 2.89 ± 0.49 for patients, t(16) = −0.06, p = 0.95, 95% CI [−0.31, 0.29], Dz = 0.01 (Fig. 3E, F).

Exploratory analysis

In the longitudinal data frontal cortex, parietal cortex, ACC, PCC, insula, hippocampus and thalamus show higher BPND after ICBT. In the cross-sectional data hippocampus show higher BPND in patients at baseline compared to controls (Supplement 1, Table S2 and S3).

Change in MADRS-S was not a significant predictor of PET2 BPND, when controlling for PET1 BPND (B1 = 0.007, SE = 0.27, t = 0.03, p = 0.98). We also included an interaction effect between baseline BPND and MADRS-change. However, neither MADRS-change (p = 0.82), nor the interaction term (p = 0.65) was significant. No significant association was observed between baseline MADRS-S and PET1 BPND, r(15) = −0.24, p = 0.36.

Discussion

Here we show an increase of cerebral serotonin transporter availability in patients with MDD after symptom improvement following engagement in internet delivered CBT. This is, to our knowledge, the first published PET study assessing 5-HTT in patients with MDD before and after non-pharmacological treatment, a design informing on the within-subject change in 5-HTT availability during and after a depressive episode. The observed increase of available 5-HTT indicates a degree of plasticity in the serotonin system in vivo in MDD patients. This suggests that previously reported 5-HTT PET findings in depression are likely to reflect a temporary state rather than a trait.

The observed increase in [11C]MADAM binding can have several causes, such as (i) lower levels of serotonin in the synapse, freeing up more 5-HTT for [11C]MADAM to bind to; (ii) an increase of the number of synapses expressing 5-HTT; or, (iii), an increase of the 5-HTT concentration in existing synapses. Explanation (i) is unlikely since 5-HTT radioligands is insensitive to change in endogenous serotonin levels in humans52. As for (ii), there is evidence of synaptogenesis as part of recovery of depression53–55. However, by extension, MDD patients could then be expected to have lower concentration of all 5-HT proteins due to fewer 5-HT synapses compared to healthy controls. Though this might be the case for some proteins (e.g., 5HT1B56), it does not seem to be a general finding57. We hence suggest, that out of the three explanations above, an upregulation of 5-HTT expression, is the most likely reason for the observed increased [11C]MADAM binding.

It has been suggested that the principal function of brain serotonin is to enhance adaptive responses to adverse conditions through improving an individual’s stress tolerability8,9. In a longitudinal PET study of individuals resilient to seasonal depression, 5-HTT binding was shown to decrease in the winter58. This was interpreted as 5-HTT downregulation mediating resilience to the environmental stress of winter. This model find some support in animal data, where a PET-study in mice using corticosterone treatment to induce a state of chronic stress shows a general decrease in 5-HTT availability59. According to this model, environmental stress would decrease cerebral 5-HTT availability as (part of) an adaptive response. Some individuals will still develop MDD, after which, hypothetically, either continual environmental stress or the stress inherent to the depressive state will keep 5-HTT levels low. Pharmacological treatment inhibiting 5-HTT could here be viewed as enhancing the innate 5-HTT reduction. As the individual recovers, either due to spontaneous remission or treatment, e.g., CBT, 5-HTT levels could be expected to increase towards premorbid levels. Though our study design does not allow confirmation of a causal explanation, the results, showing an increase in 5-HTT availability after treatment, are in line with this model.

Change in [11C]MADAM binding in individual brain regions follows the same pattern as the composite ROI (Supplement 1, Table S2), with binding increasing after treatment. Most cortical regions were not included in the composite region due to an a priori decision aiming to maximize signal-to-noise. In the exploratory analysis we observed an increase in [11C]MADAM BPND of a magnitude similar to the composite region in frontal and parietal cortex but not temporal cortex.

Meta-analyses of cross-sectional 5-HTT PET-studies, published after the design of the present work, have shown higher binding in some brain regions in healthy controls compared to MDD patients. Standardized effect sizes ~0.5 has been reported19,20. We instead observed a (non-significant) numerical difference in the opposite direction both in the composite region and in individual brain regions (Supplement 1, Table S3). However, it should be noted that to reliably detect effects of D = 0.5, large sample sizes of ~100 subjects per group is needed.

We did not observe a significant correlation between the degree of improvement in MADRS-S and the amplitude of change in [11C]MADAM binding. Given our sample size, not much can be inferred from a lack of a significant association; we had adequate power only to detect a true correlation of larger magnitude (r > 0.65). To our knowledge, no consistent pattern between symptom ratings in MDD and 5-HTT availability have been reported20. It is perhaps not to be expected that MADRS-S total score, which is a composite of many different symptoms in depression, should be strongly explained by the availability of one single protein.

In the analysis of median raphe, no difference was observed between patients and controls, nor was any change in BPND detected in the longitudinal analysis. The analysis of dorsal raphe showed similar results (Supplement 1, Table S2 and S3). Due to the small size of dorsal and median raphe the TACs are noisy, making it hard to assess the kinetics for individual examinations. When deriving standardized uptake curves, averaged across subjects, it can be observed that time for maximum activity (Tmax) not is reached within the time frame of data acquisition, implying that the binding is not reversible during the time span of the PET experiment (Supplement 1: Figs. S3 and S4). If transient equilibrium is not reached true differences between populations could be difficult to detect. This should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results.

A limitation in this study is the fact that PET examinations of patients were performed between October 2014 and September 2015, while healthy controls were examined between May 2016 and October 2017. To the best of our knowledge all conditions around the PET-examinations were unchanged during this time period.

Only the patients were examined twice with PET and [11C]MADAM. This may be viewed as a limitation of the study. But as the research question was whether 5-HTT density in the brain changes as a depressed individual becomes less depressed, the cause of the improvement was not of interest. Thus, a randomized placebo-controlled design was deemed inappropriate. Indeed, it is likely that, in addition to the effects of the ICBT treatment, there was an improvement caused by time, but this is desirable and adjusting for it in the study design would do naught besides reduce statistical power. Another alternative would be to examine the controls twice – in effect a test-retest design on healthy individuals. However, there is a priori no reason to believe that the average concentration of 5-HTT in a group of healthy individuals should systematically change in any direction over a period of 11 weeks. It is also unlikely that any such difference would be big enough as to have any detectable effect in a study of N = 17. Additionally, at least seven test-retest studies have been published on 5-HTT binding radioligands39,60–64, including a study on [11C]MADAM with 4–8 weeks between test and retest published by our group28. Unsurprisingly, though point estimates of the difference scores differ between brain regions and studies, no systematical direction can be discerned. Since PET-examinations are both costly and entails exposing individuals to radiation we decided that the additional information provided by a second PET measurement of the controls not to be worth the cost

Here we demonstrate that patients in an MDD episode increase serotonin transporter availability after alleviation of depressive symptoms. Our results suggest plasticity in the serotonin system with regards to depression.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Swedish Research Council (2013-09304) and a donation from Birgitta and Sten Westerberg. Johan Lundberg and Viktor Kaldo were supported by Region Stockholm (higher clinical research appointment); Jonas Svensson was supported by the Swedish Mental Health Fund; Pontus Plavén-Sigray was supported by the Swedish Society for Medical Research and the Lundbeck Foundation. We wish to thank Professor Lars Farde for discussions on study design; Monica Hellberg, treatment coordinator at the Internet Psychiatry Clinic and all staff at the Karolinska PET-center for excellent support during the study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41398-021-01376-w.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates (WHO, 2017).

- 2.Hirschfeld RM. History and evolution of the monoamine hypothesis of depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2000;61:4–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asberg M, Träskman L, Thorén P. 5-HIAA in the Cerebrospinal Fluid. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1976;33:1193–1197. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770100055005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delgado P. Serotonin function and the mechanism of antidepressant action. Reversal of antidepressant-induced remission by rapid depletion of plasma tryptophan. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1990;47:411–418. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810170011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith KA, Fairburn CG, Cowen PJ. Relapse of depression after rapid depletion of tryptophan. Lancet. 1997;349:915–919. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warden D, Rush A, Trivedi M, Fava M, Wisniewski S. The STAR*D Project results: a comprehensive review of findings. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2008;9:449–459. doi: 10.1007/s11920-007-0061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coppen A. The biochemistry of affective disorders. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1967;113:1237–1264. doi: 10.1192/bjp.113.504.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carhart-Harris RL, Nutt DJ. Serotonin and brain function: a tale of two receptors. J. Psychopharmacol. 2017;31:1091–1120. doi: 10.1177/0269881117725915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cowen PJ, Browning M. What has serotonin to do with depression? World Psychiatry. 2015;14:158–160. doi: 10.1002/wps.20229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flory JD, Mann JJ, Manuck SB, Muldoon MF. Recovery from major depression is not associated with normalization of serotonergic function. Biol. Psychiatry. 1998;43:320–326. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00480-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ressler KJ, Nemeroff CB. Role of serotonergic and noradrenergic systems in the pathophysiology of depression and anxiety disorders. Depress. Anxiety. 2000;12:2–19. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2000)12:1+<2::AID-DA2>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charnay Y, Léger L. Brain serotonergic circuitries. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2010;12:471–487. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2010.12.4/ycharnay. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grohol, J. Top 25 psychiatric medications for 2018. PsychCentralhttps://psychcentral.com/blog/top-25-psychiatric-medications-for-2018/ (2019).

- 14.Parsey RV, et al. Lower serotonin transporter binding potential in the human brain during major depressive episodes. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2006;163:52–58. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selvaraj S, et al. Diminished brain 5-HT transporter binding in major depression: a positron emission tomography study with [11C]DASB. Psychopharmacology. 2011;213:555–562. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1660-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeh Y-W, et al. Incongruent reduction of serotonin transporter associated with suicide attempts in patients with major depressive disorder: a positron emission tomography study with 4-[18F]-ADAM. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;18:pyu065. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyu065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reimold M, et al. Anxiety is associated with reduced central serotonin transporter availability in unmedicated patients with unipolar major depression: a [11C]DASB PET study. Mol. Psychiatry. 2008;13:606–613. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cannon DM, et al. Elevated serotonin transporter binding in major depressive disorder assessed using positron emission tomography and [11C]DASB; comparison with bipolar disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2007;62:870–877. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gryglewski G, Lanzenberger R, Kranz GS, Cumming P. Meta-analysis of molecular imaging of serotonin transporters in major depression. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:1096–1103. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spies M, Knudsen GM, Lanzenberger R, Kasper S. The serotonin transporter in psychiatric disorders: insights from PET imaging. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:743–755. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varnäs K, Halldin C, Hall H. Autoradiographic distribution of serotonin transporters and receptor subtypes in human brain. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2004;22:246–260. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vertes, R. P. & Linley, S. B. in Efferent And Afferent Connections of The Dorsal and Median Raphe Nuclei in The Rat BT - Serotonin and Sleep: Molecular, Functional and Clinical Aspects (eds. Monti, J. M., Pandi-Perumal, S. R., Jacobs, B. L. & Nutt, D. J.) 69–102 (Birkhäuser Basel, 2008).

- 23.Lanzenberger R, et al. Prediction of SSRI treatment response in major depression based on serotonin transporter interplay between median raphe nucleus and projection areas. Neuroimage. 2012;63:874–881. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deakin JFW. Depression and antisocial personality disorder: two contrasting disorders of 5HT function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;64:79–93. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6020-6_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weitz ES, et al. Baseline depression severity as moderator of depression outcomes between cognitive behavioral therapy vs pharmacotherapy: an individual patient data meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:1102–1109. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carlbring P, Andersson G, Cuijpers P, Riper H, Hedman-Lagerlöf E. Internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2018;47:1–18. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2017.1401115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Titov N, et al. ICBT in routine care: a descriptive analysis of successful clinics in five countries. Internet Interv. 2018;13:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lundberg J, Halldin C, Farde L. Measurement of serotonin transporter binding with PET and [11C]MADAM: A test–retest reproducibility study. Synapse. 2006;60:256–263. doi: 10.1002/syn.20297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheehan DV, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn (DSM-4) (American Psychiatric Press, 1994).

- 31.Montgomery SA, Åsberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Svanborg P, Åsberg M. A new self-rating scale for depression and anxiety states based on the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1994;89:21–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andersson, G. et al. Internet-based self-help for depression: randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry187, 456–61 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Hedman E, et al. Effectiveness of Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for depression in routine psychiatric care. J. Affect. Disord. 2014;155:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Varrone A, et al. Advancement in PET quantification using 3D-OP-OSEM point spread function reconstruction with the HRRT. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2009;36:1639–1650. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halldin C, et al. [11C]MADAM, a new serotonin transporter radioligand characterized in the monkey brain by PET. Synapse. 2005;58:173–183. doi: 10.1002/syn.20189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lundberg J, Odano I, Olsson H, Halldin C, Farde L. Quantification of 11C-MADAM binding to the serotonin transporter in the human brain. J. Nucl. Med. 2005;46:1505–1515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matheson GJ, et al. Reliability of volumetric and surface-based normalisation and smoothing techniques for PET analysis of the cortex: a test-retest analysis using [11C]SCH-23390. Neuroimage. 2017;155:344–353. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nørgaard M, et al. Optimization of preprocessing strategies in Positron Emission Tomography (PET) neuroimaging: A [11C]DASB PET study. Neuroimage. 2019;199:466–479. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lammertsma AA, Hume SP. Simplified reference tissue model for PET receptor studies. Neuroimage. 1996;4:153–158. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Svensson JE, et al. Validity and reliability of extrastriatal [11C]raclopride binding quantification in the living human brain. Neuroimage. 2019;202:116143. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ganz M, et al. Cerebellar heterogeneity and its impact on PET data quantification of 5-HT receptor radioligands. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2017;37:3243–3252. doi: 10.1177/0271678X16686092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cselényi Z, Olsson H, Farde L, Gulyás B. Wavelet-aided parametric mapping of cerebral dopamine D2 receptors using the high affinity PET radioligand [11C]FLB 457. Neuroimage. 2002;17:47–60. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schain M, et al. Improved mapping and quantification of serotonin transporter availability in the human brainstem with the HRRT. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2013;40:228–237. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2260-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Evans, A. C. et al. 3D statistical neuroanatomical models from 305 MRI volumes. in 1993 IEEE Conference Record Nuclear Science Symposium and Medical Imaging Conference. 1813–1817 vol. 3 (IEEE, 1993).

- 46.Fischl B. FreeSurfer. Neuroimage. 2012;62:774–781. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beliveau V, et al. The structure of the serotonin system: A PET imaging study. Neuroimage. 2020;205:116240. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller JM, et al. Positron emission tomography quantification of serotonin transporter in suicide attempters with major depressive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2013;74:287–295. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beliveau V, et al. Functional connectivity of the dorsal and median raphe nuclei at rest. Neuroimage. 2015;116:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.04.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Knudsen, G. M. et al. Guidelines for the content and format of PET brain data in publications and archives: a consensus paper. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 10.1177/0271678X20905433 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Lakens D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 2013;4:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Finnema SJ, et al. Application of cross-species PET imaging to assess neurotransmitter release in brain. Psychopharmacology. 2015;232:4129–4157. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-3938-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duman RS, Aghajanian GK, Sanacora G, Krystal JH. Synaptic plasticity and depression: new insights from stress and rapid-acting antidepressants. Nat. Med. 2016;22:238–249. doi: 10.1038/nm.4050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen, F., Danladi, J., Wegener, G., Madsen, T. M. & Nyengaard, J. R. Sustained ultrastructural changes in rat hippocampal formation after repeated electroconvulsive seizures. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 10.1093/ijnp/pyaa021 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Holmes SE, et al. Lower synaptic density is associated with depression severity and network alterations. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1529. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09562-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tiger M, Varnäs K, Okubo Y, Lundberg J. The 5-HT(1B) receptor-a potential target for antidepressant treatment. Psychopharmacology. 2018;235:1317–1334. doi: 10.1007/s00213-018-4872-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Savitz JB, Drevets WC. Neuroreceptor imaging in depression. Neurobiol. Dis. 2013;52:49–65. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mc Mahon B, et al. Seasonality-resilient individuals downregulate their cerebral 5-HT transporter binding in winter – a longitudinal combined 11C-DASB and 11C-SB207145 PET study. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;28:1151–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reisinger SN, Wanek T, Langer O, Pollak DD. PET imaging of the mouse brain reveals a dynamic regulation of SERT density in a chronic stress model. Transl. Psychiatry. 2019;9:80. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0416-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim JS, Ichise M, Sangare J, Innis RB. PET imaging of serotonin transporters with [11C]DASB: test–retest reproducibility using a multilinear reference tissue parametric imaging method. J. Nucl. Med. 2006;47:208–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frankle WG, et al. Estimation of serotonin transporter parameters with 11C-DASB in healthy humans: reproducibility and comparison of methods. J. Nucl. Med. 2006;47:815–826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meyer JH, et al. Occupancy of serotonin transporters by paroxetine and citalopram during treatment of depression: a [11C]DASB PET Imaging Study. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2001;158:1843–1849. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Praschak-rieder, N. et al. Effects of tryptophan depletion on the serotonin transporter in healthy humans. Biol. Psychiatry10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.038 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Ogden RT, et al. In vivo quantification of serotonin transporters using [(11)C]DASB and positron emission tomography in humans: modeling considerations. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2007;27:205–217. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.