Abstract

Frailty is a geriatric syndrome characterized by age-related declines in function and reserve resulting in increased vulnerability to stressors. The most consistent laboratory finding in frail subjects is elevation of serum IL-6, but it is unclear whether IL-6 is a causal driver of frailty. Here, we characterize a new mouse model of inducible IL-6 expression (IL-6TET-ON/+ mice) following administration of doxycycline (Dox) in food. In this model, IL-6 induction was Dox dose-dependent. The Dox dose that increased IL-6 levels to those observed in frail old mice directly led to an increase in frailty index, decrease in grip strength, and disrupted muscle mitochondrial homeostasis. Littermate mice lacking the knock-in construct failed to exhibit frailty after Dox feeding. Both naturally old mice and young Dox-induced IL-6TET-ON/+ mice exhibited increased IL-6 levels in sera and spleen homogenates but not in other tissues. Moreover, Dox-induced IL-6TET-ON/+ mice exhibited selective elevation in IL-6 but not in other cytokines. Finally, bone marrow chimera and splenectomy experiments demonstrated that non-hematopoietic cells are the key source of IL-6 in our model. We conclude that elevated IL-6 serum levels directly drive age-related frailty, possibly via mitochondrial mechanisms.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11357-021-00343-z.

Keywords: Frailty, IL-6, Mouse, Transgenic models

Introduction

Frailty Syndrome (FS) is an increasingly recognized geriatric syndrome. FS represents a clinical state of age-related vulnerability to stressors resulting in a high risk of adverse health outcomes, including disability, hospitalization, institutionalization, and death [17, 24, 25]. Its prevalence is 20-30% in adults older than 75, and its health and healthcare consequences are massive, approaching those of Alzheimer’s dementia. FS is characterized by reduced physiological reserve and function across multiple organ systems including the musculoskeletal, neuroendocrine/metabolic, and immune systems. Defining and diagnosing FS in humans and developing animal models has been challenging. Two main diagnostic models have been proposed. The Frailty Phenotype (FP) model defines FS using five criteria: weight loss, exhaustion, weakness, slowness, and reduced physical activity [8]. A mouse counterpart consists of four criteria established in old (27-28 months) wild-type (WT) mice [20] or in IL-10-knockout (IL-10-/-) mice [33]. The Frailty Index defines frailty by counting the number of deficits, disabilities, and impairments, including psychosocial risk factors [28]. FI has been translated to mice, and the murine frailty index (FI) correlates well to the human FI [34]. The mechanistic basis of FS remains obscure, in part due to a dearth of relevant animal models that recapitulate the features of human FS. Leading theories focus on inflammatory dysregulation, mitochondrial and energy imbalance, or a combination of the two [24, 25, 32].

The most consistent laboratory finding in FS is an elevation of IL-6, a pleiotropic cytokine with roles in immunity, hematopoiesis, and inflammation. IL-6 was originally defined by its ability to promote activation and proliferation of T cells and differentiation of B cells [10]. IL-6 is produced by most immune cells, adipocytes, skeletal muscle, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells. Cell types react to IL-6 via two mechanisms: “classical-signaling” and “trans-signaling.” Classical-signaling occurs through the “classical” IL-6 receptor, IL-6R (CD126), a dimer composed of an 80-kilodalton type 1 cytokine receptor subunit, which binds IL-6 and gp130 [9], a universally expressed 130-kilodalton signal-transducing receptor subunit. IL-6R is expressed by various immune cells, epithelial cells, and fibroblasts [12]. In contrast, IL-6 trans-signaling occurs when soluble IL-6R (sIL-6R) binds secreted IL-6, increasing its circulating half-life and binding to membrane-bound gp130. Because virtually all cells express gp130, IL-6 trans-signaling expands the cell types affected by IL-6. IL-6 exhibits hormone-like attributes that affect vascular homeostasis, lipid metabolism, insulin resistance, mitochondrial function, and the neuroendocrine system and behavior. Acutely, IL-6 crosses the blood-brain barrier to promote fever by inducing the synthesis of prostaglandins in brain endothelial cells [7].

Physiological concentrations of IL-6 in human serum are low (mean 1–3 pg/ml; range 0.2-15 pg/ml [19], but are elevated during disease and can increase >1,000-fold in sepsis [4]. Serum IL-6 levels of 5-25 pg/ml have been correlated with frailty [31] and all-cause mortality [2]. It is unclear to what extent elevated IL-6 may contribute to reduced resilience and other adverse effects in FS individuals.

This study was aimed to bridge some of the above gaps and to elucidate a singular question: to what extent can a single cytokine, IL-6, in isolation, recapitulate features of FS in mice. Thus, we generated and characterized a mouse model with inducible IL-6 expression. We show that induction of IL-6, within the range of that seen in old frail mice, induces early onset of frailty in the absence of measurable induction of other cytokines. Our results for the first time demonstrate a causal connection between levels of a single cytokine and frailty in a mouse model.

Materials and methods

Mice and frailty assessments

Adult and old (18–26 months old) male and female C57BL/6 (B6) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and the NIA breeding colony (Charles River Laboratories), respectively. Mice were maintained in specific pathogen-free conditions at the University of Arizona, and experiments were conducted under guidelines and approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Arizona.

To generate mice with inducible IL-6 expression, we inserted a regulatory cassette containing a CMV promotor-driven neo gene together with transcription-abrogating Westphal STOP sequence followed by a tetracycline operator (tetO) sequence between the promotor and the first exon of the IL-6 gene. The resulting mice with the Flexible Accelerated STOP TetO knocked in the IL-6 gene (FAST.IL-6 mice) were crossed to ROSA26-rtTA (reverse tetracycline controlled transactivator) mice (Jax ref. # 006965) leading to the generation of IL-6TET-ON/+ mice. The mice were generated by Ingenious Targeting Laboratory technologies (New York, USA).

A grip strength meter (Columbus Instruments; Columbus, OH, USA) was used to measure forelimb grip strength. Frailty was assessed by murine frailty index (FI) consisting of 31 health-related variables as previously described [34]. Body temperature was measured with a rectal temperature probe for mice (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, USA).

Bone marrow chimera and splenectomies

Bone marrow chimera were generated using bone marrow from the femur, tibia, and pelvis of CD45.1 C57B/6 or B6.IL-6TET-ON/+ mice. Recipient mice were irradiated with one dose of 9.5 Gy (Gammacell 40 CS-137 irradiator, Best Theratonics, Ottawa, Canada), and donor cells were injected intravenously (10×106 bone marrow cells per mouse). Eight weeks post-irradiation, mice were bled, chimerism assessed by flow cytometry, and animals induced with Dox diet as above. Mice were splenectomized as described, under isoflurane anesthesia with ketamine/xylazine/XX premedication and postoperative analgesia. Briefly, right flank skin was removed, abdominal wall opened under the right rib cage, and spleen exposed and held with anatomical forceps. Blood vessels underneath the spleen were ligated using 17-mm coated vicryl surgical suture thread (Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey). Abdominal wall was sutured using the same thread, and skin was closed with Clay-Adams clips, that were removed 7-9 days post-surgery. Splenectomized mice were induced with Dox food or 5 μg LPS/mouse intraperitoneally 2 weeks following surgery to allow recovery after surgical stress.

RT-qPCR analysis of mRNA

Total RNA was isolated from spleen and gastrocnemius tissue with TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). The iScript Advanced cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The generated cDNA was used with the SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix reagent (Bio-Rad). The relative mRNA expression of all genes was determined by the 2− ΔΔCt method, and mouse actin RNA was used as a reference for normalization (see Suppl. Table 1 for Primer pairs).

Cytokine measurements

Serum levels of IL-6 were measured by ELISA (Biolegend, San Diego, USA). Spleens, gastrocnemius muscle, and fat pads were homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline in the presence of protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) and 0.5% NP-40 detergent. The levels of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-17A, IL-23, IL-27, MCP-1, IFN-β, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and GM-CSF in various tissue homogenates were measured by Legendplex multiplex assay (Biolegend).

Flow cytometry

Cells were stained with surface antibodies, followed by staining with live/dead fixable dye (biolegend) and then fixed and permeabilized using either the FoxP3 Fix/Perm kit (eBioscience, San Diego, USA) or the Fix/Perm kit (BD Bioscience, Franklin Lakes, USA) followed by staining with intracellular antibodies. Data was acquired using the Fortessa flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Co., Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) analyzed with the FlowJo software (Flow jo LLC, Ashland, OR USA). To determine the gates of positivity, fluorescence minus one controls were used. Six hours prior to analysis of intracellular expression of IL-6 mice were injected with 250 μg of Brefeldin A (BFA) (Sigma-Aldrich) and their spleens were harvested in RPMI1640 media (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) containing 10 μg BFA.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA) or SPSS (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY). Differences were calculated by Student’s t-test, Mann Whitney U-test, or one-way ANOVA. All data denote mean ± SEM unless otherwise noted. Symbols indicate individual mice.

Results

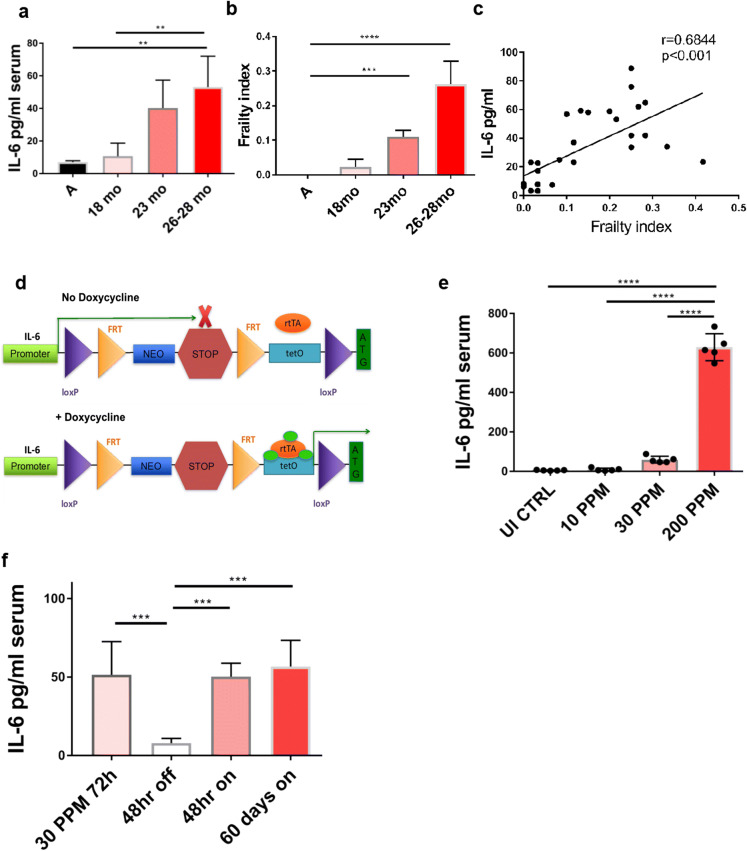

We examined C57BL/6 mice of increasing ages to determine the physiological level of serum IL-6 during aging and its connection to frailty. Frailty was quantified using the frailty index (FI) consisting of 31 health-related variables [34] and in parallel measured serum IL-6 levels in adult mice (3 mo) and old mice of increasing age (18, 23, and 26-28 mo). Mice 18-month of age, commonly used in experiments as “old” per accepted definition [22], did not show elevation of IL-6 or FI (Fig. 1). Mice at and over 23 months exhibited increased IL-6 levels (40.25 pg/ml ± 7.65) compared to adults (7.092 pg/ml ± 0.372), while 26-28 mo mice exhibited the highest IL-6 levels (53.12 pg/ml ± 5.47) (Fig. 1a). Frailty indices in these mice (Fig. 1b) tracked along with IL-6 levels with 23 mo mice but continued to increase in 26-28 mo mice and correlated with IL-6 levels in serum (Fig. 1c, r = 0.68). We conclude that only mice older than the standard cutoff age of 18 months exhibit increased FI and IL-6 levels.

Fig. 1.

Increased IL-6 and frailty with age. WT C57BL/6 male and female mice of varying ages (A, 6 mo) were bled retro-orbitally and their a serum IL-6 levels were measured by ELISA. b frailty was assessed by frailty index (FI) consisting of 31 health-related variables. c IL-6 serum levels were correlated with frailty index in individual mice (R2=0.7131). Scheme of generation of inducible IL-6 mice. d Mice with Flexible Accelerated STOP TetO knocked in the IL-6 gene (F.A.S.T. IL-6 mice) were crossed to ROSA-rtTA (reverse tetracycline-controlled transactivator) mice resulting in generation of IL-6TET-ON/+ mice. In the presence of doxycycline, rtTA binds the tetO sequence allowing for IL-6 transcription. e Adult IL-6TET-ON/+ mice fed 30 ppm Dox for 7 months exhibited serum IL-6 to levels seen in 28-month-old mice. f Switching mice on and off Dox diet resulted in on/off pattern of increase and decrease in serum IL-6 levels. a–c data pooled from two independent experiments (total N=32). e–f data representative of two independent experiments with N=5 per group. *p<0.05; **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001

To evaluate whether this relationship is causal, we generated a mouse with inducible expression of IL-6 on a C57BL/6 (B6) background using the Flexible Accelerated STOP Tetracycline Operator (FAST) expression system [30]. A regulatory cassette containing a CMV promotor-driven neo gene together with transcription-abrogating Westphal STOP sequence followed by a tetracycline operator (tetO) sequence were inserted as a knock-in between the promotor and the first exon of the IL-6 gene (Fig. 1d). Crossing the ROSA26-rtTA (reverse tetracycline controlled transactivator) mice (Jax ref. # 006965) to homozygous FAST.B6.IL-6 mice led to the generation of IL-6TET-ON/+ mice. Doxycycline (Dox) binds to and activates rtTA which then binds to the tetO sequence in the modified IL-6 gene and initiates its transcription (Fig. 1d). Because the targeted allele is not tissue-specific, Dox administration in these mice theoretically should result in the overexpression of IL-6 in various tissues, allowing us to broadly regulate IL-6 protein expression. We generated our test strain as heterozygous IL-6TET-ON/+ mice, with one copy of the WT IL-6 allele to enable near-physiological IL-6 expression in the absence of Dox. To control for side-effects of Dox, we used Dox-fed WT B6 littermate mice and mice with the IL-6-targeted allele but without the rtTA.

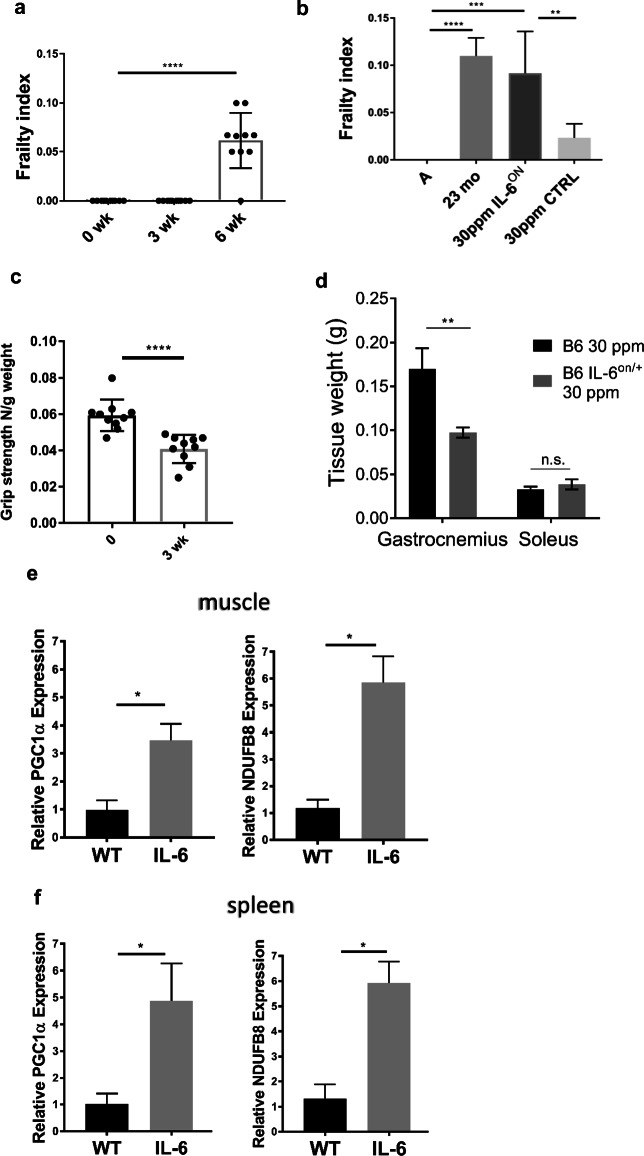

We aimed to overexpressed IL-6 in adult mice to levels comparable to those observed in old, frail mice (26-28 mo). To that effect, Dox was titrated in food over a 100x range and we found that 30 parts per million (ppm) Dox-induced IL-6 to levels similar to the range seen in 26-28 mo old B6 mice (59.24 ± 7.54) (Fig. 1e). The kinetics of IL-6 induction was determined by administrating DOX in an ON/OFF manner. Dox administration for 72 increased IL-6 to >50 pg/ml and 48 h withdrawal decreased IL-6 to baseline levels similar to wt adults (7.93 ± 0.93) pg/ml (Fig.1f). Re-feeding of DOX for 48 increased serum IL-6 above 50 pg/ml, maintaining the same level during 60-day after DOX administration, demonstrating that IL-6 levels were sustained at the same level for 60 days. Overexpression of IL-6 by the 30 ppm Dox diet resulted in increase in the FI to 0.06 which was evident 6 weeks after induction (Fig. 2a). After 7 months of Dox diet, 10 mo old mice had frailty scores equivalent to 23 mo old WT B6 mice and significantly greater than control mice fed Dox diet for the same period (p=0.0028; Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

IL-6 overexpression results in increased frailty. IL-6TET-ON/+ mice on Dox diet exhibited a an increase in frailty index scores after six weeks, b reduced grip strength after 3 weeks, and c after 7 months induction, 10 mo old mice had frailty scores equivalent to much older mice. d gastrocnemius, but not soleus muscle mass was reduced. e Relative expression of PGC1α and NDUFB8 normalized to β-actin were increased in the gastrocnemius muscle and f spleen. Data representative of 2 experiments, with n=5 mice/expt. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p< 0.0001

IL-6TET-ON/+ mice treated with 30 ppm Dox for 21 days exhibited no elevation in body temperature (Sup. Fig. 1A) or loss of body weight (Sup. Fig. 1B) but did exhibit reduced grip strength and gastrocnemius (but not soleus) muscle mass loss (Fig. 2c, d). We analyzed muscle mitochondrial response to IL-6, and found that, concurrent to loss of muscle mass, PGC1α and NDUFB8 mRNA increased 3-6 fold in the gastrocnemius muscle and spleen (Fig. 2e, f). PGC-1α is a “master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis and NDUFB8 is an electron transport chain protein. These data provide evidence that these proteins are responding to stress and act in an attempt to maintain mitochondrial homeostasis, with PGC-1α also potentially playing a protective role in inflammatory responses [14].

Dox is an antibiotic known to induce side effects in humans, including weakness, tiredness, muscle, and joint aches in 1-10% of subjects [6]. However, analysis of non-inducible littermate (B6.IL-6+/+) mice fed a Dox diet showed no changes in IL-6 levels compared to adult WT mice or homozygous IL-6TET-ON mice which did not receive Dox diet (Sup. Fig. 2A). This indicated that Dox alone did not affect IL-6 levels in mice lacking the knock-in construct. Next, the possibility that Dox diet might affect some of measured phenotypes in non-inducible mice was addressed. No difference in grip strength (Sup. Fig. 2B) or frailty (FI=0, not shown) was observed after 6 weeks of Dox diet. Splenic cellularity was increased in IL-6TET-ON/+ mice fed 30 ppm Dox diet compared to age-matched WT controls but not in littermate controls fed the same diet (Sup. Fig. 2C). Thus, the observed phenotypes in mice fed 30 ppm Dox diet were due to IL-6 induction and not Dox side-effects.

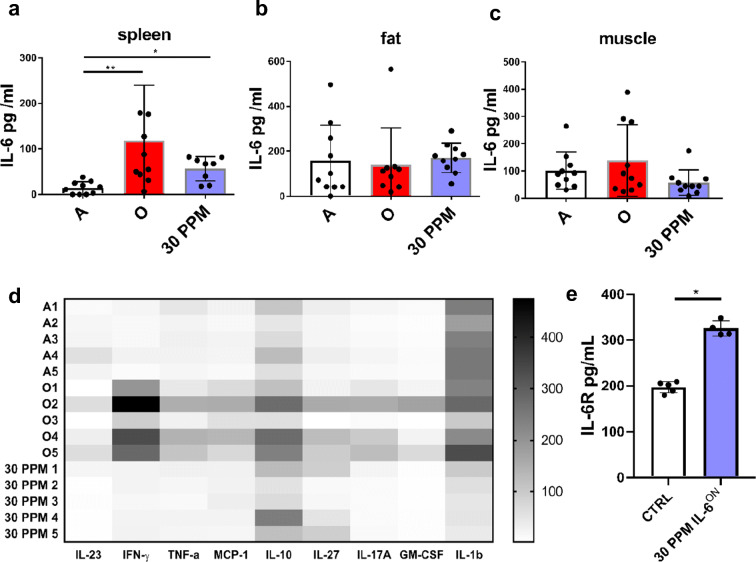

Under normal conditions, some of the main producers of IL-6 are various immune cells, adipocytes, and skeletal muscle [21, 27]. Therefore, IL-6 levels were measured in spleen, gastrocnemius muscle, and fat pad homogenates as potential sources of IL-6. WT mice (26-28mo) displayed increased levels of IL-6 in spleen homogenates but not in muscle or fat (Fig. 3a–c). No signs of deregulated widespread IL-6 expression were detected; rather, they mirrored expression of IL-6 in tissues in old WT mice (Fig. 3b, c).

Fig. 3.

IL-6 is increased in spleen homogenates. a IL-6 levels were measured in spleen homogenates of adult (4 mo), old (26-28mo), and IL-6TET-ON/+ mice fed 30 ppm dox diet for two months. b IL-6 levels of the same mice were measured in fat and c muscle homogenates. d Multiplex cytokine analysis of splenic homogenates from 4 mo WT mice (top 5 rows), 28 mo WT mice (middle 5 rows), and 30 ppm Dox-induced IL-6TET-ON/+ mice (bottom 5 rows). e ELISA measures of soluble IL-6R demonstrate significant increase in serum of Dox-induced (30 ppm) mice. n=5/group, representative of 2 experiments. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001

To investigate the possibility that IL-6 may induce other cytokines following doxycycline induction, we performed a multiplex cytokine/chemokine analysis in spleen homogenates. Compared to 4 mo WT mice (top 5 rows), 28 mo WT mice (middle 5 rows) exhibited elevation in IFN-γ, TNF-α, MCP-1, IL-10, and IL-23 in spleens (Fig. 3d) in addition to elevation in IL-6 (Fig. 1a). In contrast, Dox-induced IL-6TET-ON/+ mice (bottom 5 rows) showed that IL-10 remained increased and IL-1β decreased but no other cytokines increased to age-matched 4-mo WT mice. Induction of IL-6 was also accompanied by increased serum levels of sIL-6R (Fig. 3e), suggesting that the potential for trans-signaling in dox-induced mice was increased.

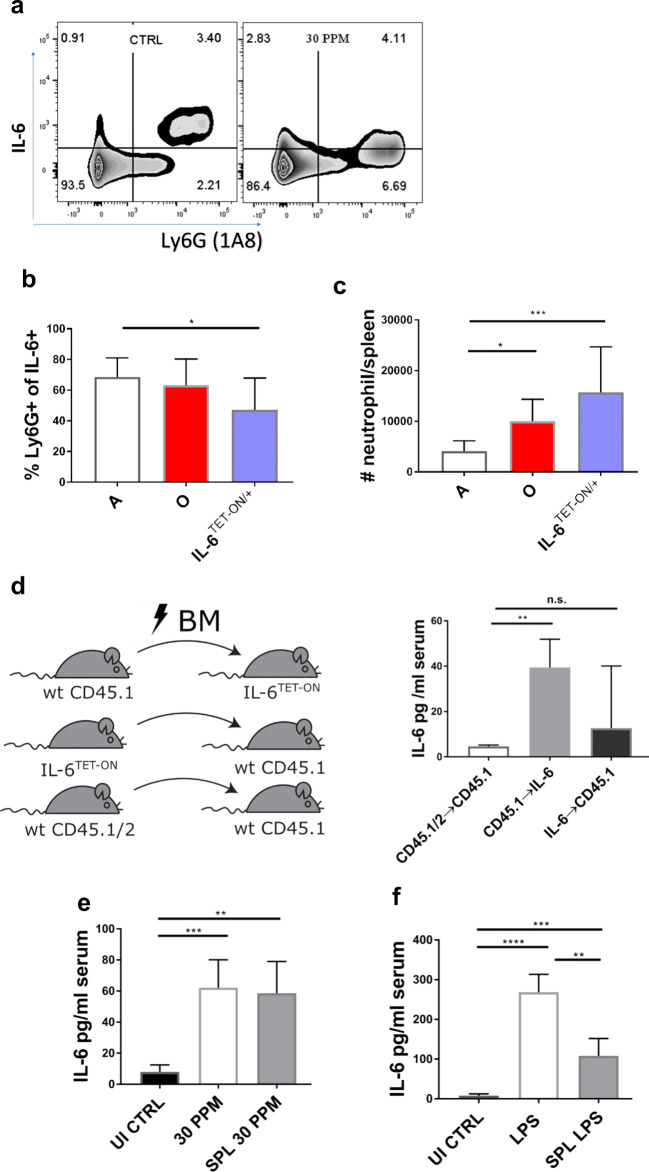

Because IL-6 levels increased in spleen homogenates of both old and dox-induced IL-6TET-ON/+ mice, we measured IL-6 production in the spleen using brefeldin A in vivo administration followed by flow cytometry. Cells expressing Ly6G, as detected by antibody clone 1A8, previously shown to bind neutrophils and not monocytes [3], exhibited the highest IL-6 median fluorescence intensity (MFI) in control mice (Fig. 4A). This would indicate that IL-6 is highest in neutrophils among all immune cells in the spleen. In induced IL-6Tet-ON/+ mice, the intensity of IL-6 in neutrophils was reduced (by 2.3-fold; CTRL= 996 ± 10, IL-6TET-ON/+ =423 ± 19; p=0.02). When we focused on all IL-6 positive cells by selective gating, we observed that more than half expressed Ly6G (Fig. 4b) in adult and old mice, suggesting that neutrophils were the largest naturally-IL-6 producing subpopulation. However, this number was reduced in induced IL-6TET-ON/+ mice, suggesting that there was increased IL-6 production from other cells. Old mice and 30 ppm IL-6TET-ON/+ mice also both exhibited increased splenic cellularity and increased neutrophil absolute counts (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Neutrophils are the main producers of IL-6 in spleens of aged mice. a Flow cytometric plot shows Ly6G (A81) positive cells have the highest intracellular expression (MFI) of IL-6 in A WT mice which is reduced in IL-6TET-ON/+ mice. b Most IL-6+ cells were expressing Ly6G (A81) in adult and old WT mice but to a lesser extent in IL-6TET-ON/+ mice. c Absolute counts of neutrophils were increased in spleens of old (26-28 mo) mice and 30 ppm induced mice. d Mixed bone marrow chimeras were able to induce IL-6 when IL-6TET-ON/+ cells were of non-hematopoietic origin. e Splenectomized IL-6TET-ON/+ mice induced IL-6 to same levels as non-splenectomized mice in response to Dox food (30 PPM). f Same mice exhibited decreased induction of serum IL-6 in response to LPS stimulation (5 μg/mouse, 6 h, intraperitoneal injection). b, c Data pooled from two experiments with N=5/group. d Data from one experiment with N=8/group. e, f data representative of two experiments with N=3-5 mice per group. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001.

Immune cells in the spleen are known to be a major source of IL-6 in the acute phase responses, as splenectomy dramatically decreases IL-6 serum levels induced by endotoxin [23] or in sepsis models [5]. Thus, increased spleen cellularity and IL-6 levels in spleen homogenates pointed to the spleen as the potential source of increased serum IL-6 levels, at least in old WT mice. However, the IL-6TET-ON/+ mice are predicted to exhibit ectopic expression enabling multiple tissues to produce IL-6. To test contributions of hematopoietic vs. non-hematopoietic cells in our model, we made bone marrow chimeras where either the cells of hematopoietic or non-hematopoietic origin were IL-6TET-ON/+. Donor cell engraftment was over 90% in both groups of recipients (Sup. Fig. 3). Consistent with the data from Fig. 4A-C., chimeric mice in which only the non-hematopoietic cells expressed the transgene were able to increase IL-6 serum levels in response to Dox diet (Fig. 4d), suggesting that the main source of IL-6 induction in our model was the non-hematopoietic cells. This idea was further supported by splenectomy of IL-6 inducible mice; splenectomized IL-6TET-ON/+ mice induced with 30 ppm Dox diet exhibited an increase serum IL-6 levels to the same levels as control mice with intact spleens (Fig. 4e). However, when the same mice were challenged with a physiological inducer of IL-6, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) endotoxin, the splenectomized mice increased serum IL-6 to much lower levels than control mice (Fig. 4f). Therefore, while the spleen may be a major producer of IL-6 in the physiological acute phase response, its presence was not necessary for serum IL-6 level increase in IL-6TET-ON/+ mice.

Discussion

In this study, we show for the first time a direct causal relationship between IL-6 and frailty. We generated a mouse model with inducible IL-6 expression and titrated the amount of Dox diet needed to increase serum IL-6 to levels similar to that observed in old (26-28 months) mice. These mice exhibited an increase in frailty index and decrease in muscle grip strength after dox-induced IL-6 overexpression, demonstrating the direct effect of IL-6 on frailty.

A few studies have explored natural murine frailty during aging in unmanipulated laboratory mice (mostly on the C57BL/6 genetic background) [13]. While such studies provide an ideal set-up to study the impact of frailty on health, they suffer from two caveats. First, the manifestations of frailty are highly varied and often affect only a small subset of mice (~9%), even at a very old age (28 months) [20], increasing study costs while reducing its power. Second, this model makes it difficult to discriminate whether a given molecule is connected to frailty causally or spuriously. To date, the main genetically targeted FS model has been the germline knockout of IL-10 [18]. IL-10-/- mice display markers of FS from 12 months of age, and have provided valuable initial interrogation of murine frailty [1, 15, 29, 33]. However, this model also has limitations. IL-10-/- mice exhibit severe immunodeficiency, with defects in T regulatory cells, and are prone to gastrointestinal and other autoimmunity disorders. They lack the main anti-inflammatory axis from conception, resulting in constitutive unchecked and mis-regulated NF-kB-mediated inflammation. After 12 months of age, these mice begin to exhibit loss of grip strength, muscle mass (sarcopenia), and weight [16, 33]; they also exhibit high levels of inflammatory cytokines IL-1α and β, IL-6, IFNγ, and TNFα, preventing causality assignment to any individual cytokine. This and other pleiotropic health alterations further urge caution in extrapolating interpretations to normal mouse or human aging. Another model, the Nfkb1-/- mouse, suffers from severe fetal immunodeficiency that continues into adulthood and culminates in a progeroid syndrome, severely confounding interpretation [26]. Finally, Sod1-KO mice, which lack the antioxidant enzyme Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase, exhibit increased frailty [11]. Although these mice recapitulate some features of human frailty (low physical activity, weakness, and exhaustion) similarly to other murine frailty models, they show broad inflammatory dysregulation, rendering examination of the mechanisms of frailty difficult. Importantly, none of the above models of frailty are based on an observation that parallels findings in human frailty, as IL-10, Nfkb1, and Cu/Zn Sod do not appear reliably reduced, much less absent, in human frailty.

Unlike these existing murine frailty models, we have started from a known and reproducible observation—moderate IL-6 elevation—seen in human and mouse frailty. We generated a model in which we can increase IL-6 in isolation and to a desired physiologically relevant level. Our mice specifically increased IL-6 and not other inflammatory cytokines measured. This allowed us to demonstrate that IL-6 is a causal mediator of several cardinal manifestations of frailty, providing a potentially valuable first step for mechanistic dissection of frailty in mice.

Muscle atrophy is associated with frailty and aging. Our IL-6 inducible model of frailty revealed a decrease in grip strength and gastrocnemius tissue. We aimed to examine mitochondrial homeostasis in IL-6-induced frailty and have found that PGC1α, master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, and NDUFB8, an electron transport chain protein were increased 3-6 fold in gastrocnemius muscle and spleen. While our initial hypothesis proposed that these proteins would be decreased in the presence of the loss of grip strength and tissue weight, the marked increase in PGC-1α and NDUFB8 may result from a compensatory response that is insufficient to maintain basal function. Further studies are needed to elucidate the interplay between IL-6 and muscle wasting mechanisms.

A limitation of our model is that the targeted allele construct allows ectopic expression of IL-6, which could present a potential discrepancy in cellular sources of IL-6 between WT and IL-6TET-ON/+ mice. Presently, tissue and cellular sources of elevated IL-6 in murine or human advanced aging and frailty are unknown. Some of the main tissue sources of IL-6 include spleen, muscle, and adipose tissue [21]. Of the three, we have observed an increase in IL-6 levels only in the spleen of aged WT mice, pointing to the spleen as a potential source of IL-6 under normal aging. However, IL-6TET-ON/+ mice were able to induce IL-6 even after splenectomy or in chimeric mice where only non-hematopoietic cells expressed the targeted alelle, confirming ectopic expression of IL-6 in our model. It will be of interest to dissect whether the precise source of IL-6 actually matters to the development (and perhaps type) of frailty. Regardless, our model provides a controllable and defined system to induce features of frailty “on demand” and should be of use in further studies of this important medical syndrome.

Supplementary Information

(PDF 259 kb)

(PDF 51.9 kb)

Funding

This study was supported by the Bowman Professorship in Medical Sciences and by generous philanthropic support of Sperry and Donnalyn van Langevelt to J. N-Ž.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Akki A, Yang H, Gupta A, Chacko VP, Yano T, Leppo MK, Steenbergen C, Walston J, Weiss RG. Skeletal muscle ATP kinetics are impaired in frail mice. Age (Dordr) 2014;36(1):21–30. doi: 10.1007/s11357-013-9540-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baune BT, Rothermundt M, Ladwig KH, Meisinger C, Berger K. Systemic inflammation (Interleukin 6) predicts all-cause mortality in men: results from a 9-year follow-up of the MEMO Study. Age (Dordr) 2011;33(2):209–217. doi: 10.1007/s11357-010-9165-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daley JM et al (2007) Use of Ly6G-specific monoclonal antibody to deplete neutrophils in mice. 10.1189/jlb.0407247. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Damas P et al (1991) Cytokine serum level during severe sepsis in human IL-6 as a marker of severity, pp. 356–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Drechsler S et al (2018) Splenectomy modulates early immuno-inflammatory responses to trauma-hemorrhage and protects mice against secondary sepsis. Sci Rep. Springer US, (September), pp. 1–12. 10.1038/s41598-018-33232-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Eger K, Hermes M, Uhlemann K, Rodewald S, Ortwein J, Brulport M, Bauer AW, Schormann W, Lupatsch F, Schiffer IB, Heimerdinger CK, Gebhard S, Spangenberg C, Prawitt D, Trost T, Zabel B, Sauer C, Tanner B, Kolbl H, Krugel U, Franke H, Illes P, Madaj-Sterba P, Bockamp EO, Beckers T, Hengstler JG. 4-Epidoxycycline: an alternative to doxycycline to control gene expression in conditional mouse models. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;323(3):979–986. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eskilsson A, Mirrasekhian E, Dufour S, Schwaninger M, Engblom D, Blomqvist A. Immune-induced fever is mediated by IL-6 receptors on brain endothelial cells coupled to STAT3-dependent induction of brain endothelial prostaglandin synthesis. J Neurosci. 2014;34(48):15957–15961. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3520-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hibi M, Murakami M, Saito M, Hirano T, Taga T, Kishimoto T. Molecular cloning and expression of an IL-6 signal transducer, gp130. Cell. 1990;63(6):1149–1157. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90411-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunter CA, Jones SA. IL-6 as a keystone cytokine in health and disease. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(5):448–457. doi: 10.1038/ni.3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson MJ, et al. A new mouse model of frailty: the Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase knockout mouse. GeroScience. 2017;39(2):187–198. doi: 10.1007/s11357-017-9975-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones SA, Scheller J, Rose-John S. Therapeutic strategies for the clinical blockade of IL-6/gp130 signaling. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(9):3375–3383. doi: 10.1172/JCI57158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kane AE, Sinclair DA. Frailty biomarkers in humans and rodents: current approaches and future advances. Mech Ageing Dev. 2019;180:117–128. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang C, Ji LL. Role of PGC-1α signaling in skeletal muscle health and disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1271(1):110–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06738.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ko F, Abadir P, Marx R, Westbrook R, Cooke C, Yang H, Walston J. Impaired mitochondrial degradation by autophagy in the skeletal muscle of the aged female interleukin 10 null mouse. Exp Gerontol. 2016;73:23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ko F, Yu Q, Xue QL, Yao W, Brayton C, Yang H, Fedarko N, Walston J. Inflammation and mortality in a frail mouse model. Age (Dordr) 2012;34(3):705–715. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9269-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuchel GA. Frailty and resilience as outcome measures in clinical trials and geriatric care: are we getting any closer? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:1451–1454. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kühn R, Löhler J, Rennick D, Rajewsky K, Müller W. Interleukin-10-deficient mice develop chronic enterocolitis. Cell. 1993;75(2):263–274. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80068-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laffon B (2018) Frailty in older adults is associated with plasma concentrations of inflammatory mediators but not with lymphocyte subpopulations, 9(May), pp. 1–9. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Liu H, Graber TG, Ferguson-Stegall L, Thompson LV. Clinically relevant frailty index for mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(12):1485–1491. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maggio M, Guralnik JM, Longo DL, Ferrucci L. Interleukin-6 in aging and chronic disease: a magnificent pathway. J Gerontol- Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(6):575–584. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.6.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller RA, Nadon NL. Principles of animal use for gerontological research. J Gerontol: Ser A. 2000;55(3):B117–B123. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.3.B117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moeniralam HS, Bemelman WA, Endert E, Koopmans R, Sauerwein HP, Romijn JA. The decrease in nonsplenic interleukin-6 (IL-6) production after splenectomy indicates the existence of a positive feedback loop of IL-6 production during endotoxemia in dogs. Infect Immun. 1997;65(6):2299–2305. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2299-2305.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohler MJ, Fain MJ, Wertheimer AM, Najafi B, Nikolich-Žugich J. The Frailty syndrome: clinical measurements and basic underpinnings in humans and animals. Exp Gerontol. 2014;54:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morley JE, Vellas B, Abellan van Kan G, Anker SD, Bauer JM, Bernabei R, Cesari M, Chumlea WC, Doehner W, Evans J, Fried LP, Guralnik JM, Katz PR, Malmstrom TK, McCarter RJ, Gutierrez Robledo LM, Rockwood K, von Haehling S, Vandewoude MF, Walston J. Frailty consensus: a call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(6):392–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Passos F et al (2014) Chronic inflammation induces telomere dysfunction and accelerates ageing in mice. 10.1038/ncomms5172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Pedersen BK, Steensberg A, Schjerling P. Muscle-derived interleukin-6: possible biological effects. J Physiol. 2001;536(2):329–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0329c.xd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rockwood K, Hogan DB, MacKnight C. Conceptualisation and measurement of frailty in elderly people. Drugs Aging. 2000;17(4):295–302. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200017040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sikka G, Miller KL, Steppan J, Pandey D, Jung SM, Fraser CD, III, Ellis C, Ross D, Vandegaer K, Bedja D, Gabrielson K, Walston JD, Berkowitz DE, Barouch LA. Interleukin 10 knockout frail mice develop cardiac and vascular dysfunction with increased age. Exp Gerontol. 2013;48(2):128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanaka KF, Ahmari SE, Leonardo ED, Richardson-Jones JW, Budreck EC, Scheiffele P, Sugio S, Inamura N, Ikenaka K, Hen R. Flexible Accelerated STOP Tetracycline Operator-Knockin (FAST): a versatile and efficient new gene modulating system. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(8):770–773. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Epps P, et al. Frailty has a stronger association with inflammation than age in older veterans. Immun Ageing. 2016;13(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12979-016-0082-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von Zglinicki T, Varela-Nieto I, Brites D, Karagianni N, Ortolano S, Georgopoulos S, Cardoso AL, Novella S, Lepperdinger G, Trendelenburg AU, van Os R. Frailty in mouse ageing: a conceptual approach. Mech Ageing Dev. 2016;160:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walston J, Fedarko N, Yang H, Leng S, Beamer B, Espinoza S, Lipton A, Zheng H, Becker K. The physical and biological characterization of a frail mouse model. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(4):391–398. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.4.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitehead JC, Hildebrand BA, Sun M, Rockwood MR, Rose RA, Rockwood K, Howlett SE. A clinical frailty index in aging mice: comparisons with frailty index data in humans. J Gerontol- Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(6):621–632. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 259 kb)

(PDF 51.9 kb)