Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to measure the duration and recovery rate of olfactory loss in patients complaining of recent smell loss as their prominent symptom during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak.

Method

This was a prospective telephone follow-up observational study of 243 participants who completed an online survey that started on 12 March 2020.

Results

After a mean of 5.5 months from the loss of smell onset, 98.3 per cent of participants reported improvement with a 71.2 per cent complete recovery rate after a median of 21 days. The chance of complete recovery significantly decreased after 131 days from the onset of loss of smell (100 per cent sensitive and 97.7 per cent specific). Younger age and isolated smell loss were associated with a rapid recovery, whereas accompanying rhinological and gastrointestinal symptoms were associated with longer loss of smell duration.

Conclusion

Smell loss, occurring as a prominent symptom during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, showed a favourable outcome. However, after 5.5 months from the onset, around 10 per cent of participants still complained of moderate or severe hyposmia.

Key words: Olfactory Disorders, Smell, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Coronavirus

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) is an ongoing viral pandemic that started in China in December 2019 and rapidly spread to the other countries of the world.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) highlighted the triad of fever, cough and shortness of breath in the definition of a suspected and probable case of Covid-19 in the early guidelines.2 At the same time as the Covid-19 pandemic, there was a rapid increase in self-reported olfactory dysfunction.3 In February 2020, smell and taste dysfunction were identified as a symptom of Covid-19 in a survey of neurological manifestations of the disease.4 Further studies confirmed the association between Covid-19 and chemosensory dysfunction with a wide range of reported prevalence from 3.2 per cent up to 98 per cent for loss of smell.5

By 9 May 2020, studies had provided sufficient evidence for the WHO to add loss of smell alongside other less common symptoms of Covid-19, and on 7 August, patients with sudden anosmia or ageusia without a known underlying cause were defined as a probable case of Covid-19.6,7 Different factors were suggested to affect the prevalence of smell loss in various studies, including demographic factors (age, gender), the severity of the disease, and the methodology and design of the study. It seemed that smell loss was more prevalent among younger people, out-patient cases, females, Caucasians and whether the olfaction had been assessed objectively.5,8–10 Smell loss was even shown to be related to the prognosis of Covid-19. Lower hospital and intensive care unit admission rates, lower rates of acute respiratory distress syndrome or a need for intubation are associated with the presence of olfactory loss.11,12

Loss of smell after a respiratory infection is not unique to Covid-19, and viruses such as adenovirus, rhinovirus, coronavirus and influenza are already known as aetiological factors.13 Although olfactory dysfunction is often accompanied by other Covid-19 symptoms in many published reports, there is some evidence indicating that Covid-19 patients can present with chemosensory dysfunctions as their sole symptom of the disease.14 Although the prognosis of post-viral olfactory loss is not exactly clear and reported recovery rates vary in related studies, early reports, which are mostly from Europe, suggest a more favourable prognosis for olfactory loss encountered in confirmed Covid-19 cases compared with previously described post-viral olfactory loss.15,16 However, as was seen with prevalence rates, reported olfactory recovery rates vary between studies, and several factors have been reported to be associated with the prognosis of smell loss in Covid-19 cases.17–20

Healthy, young out-patients with subtle or no symptoms are not prioritised for real-time polymerase chain reaction in the diagnostic protocols in areas with limited resources.21 Because of the high incidence of olfactory dysfunction in Covid-19 cases, this study aimed to investigate the duration and recovery rate of olfactory loss encountered in cases with mild or no additional Covid-19 symptoms (with no Covid-19 confirmed tests) that occurred during the pandemic in order to indicate the factors that may influence the duration or recovery rate of olfactory dysfunction in these patients.

Materials and methods

Study population

An online survey by Bagheri et al.22 was run from 12 March to 8 April 2020. Out of 19 473 participants with smell loss, 6654 responders registered their phone numbers so their symptoms could be followed. Participants were selected for inclusion in this study if they had reported the absence of other accompanying Covid-19 symptoms (including cough, fever, shortness of breath, sore throat, myalgia, nausea or vomiting, and diarrhoea) or rhinological symptoms (including runny nose, sneeze, nasal congestion, nasal thick discharge and a need to blow the nose).

Participants aged under 18 years, or those who had mentioned a history of previous olfactory problems, chemotherapy, chronic respiratory infections, nasal polyps, head trauma, neurodegenerative diseases, receipt of specified treatment for their recent smell loss (including glucocorticoids, hydroxychloroquine or any antiviral medications) or those who could not be reached by three calls on three separate days through the provided telephone numbers were excluded.

Measurements and study design

In this prospective observational study, all eligible participants were interviewed on the telephone about the severity of recent smell loss at the onset and at the time of the interview (self-assessed by an ordinal scale from one to five corresponding to normal sense of smell, mild loss of smell, moderate loss of smell, severe loss of smell or anosmia) and the duration of the smell loss (the days since loss of smell onset to being fully recovered).23

Additional Covid-19 symptoms, presenting in one week prior until one week after the onset of loss of smell were self-graded as: no symptoms, mild symptoms, moderate symptoms and severe symptoms.24 Rhinological symptoms in the same time limits were self-assessed based on the rhinological subscale of Sino-Nasal Outcome Test-22 (a Likert scale of 1 to 5).25,26 Any diagnosis of Covid-19 by real-time polymerase chain reaction or chest imaging in the participants or their family members living in the same house or any recent smell loss in the family members was also recorded. The participants were followed up via telephone twice at least three months apart if they did not report a return of olfaction to the baseline. The patients who did not want to be followed up (despite their first consent), had not answered the questions completely (because of not remembering), had received medication during the follow ups, who reported moderate or severe rhinological or Covid-19 symptoms, or who were hospitalised were excluded from the analysis. Complete recovery was defined as self-reported restoration of smell ability, whereas partial recovery was defined as improvement in olfactory ability.

Statistical analysis

The data were described as mean and standard deviation or frequency (per cent). Chi-square or Fisher's exact test was utilised for assessing the relationship between categorical data with time to recovery categories (in correspondence with first and third quartile of time to complete recovery). Subsequently, rapid and moderately recovered patients were merged and odds ratios for measuring the effect size were calculated. The significant variables were included in multiple logistic models to assess the multiple relationships. The receiver operating characteristic curve was used to classify patients as with and without complete recovery, considering the time passed from the onset of smell loss. Kaplan–Meier estimates were reported to show the rate of complete recovery from the onset of the smell loss. All analysis was performed using SPSS® (version 24) statistical software. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Study population demographic data and symptoms

Data of 243 participants were included in the final analysis after application of inclusion and exclusion criteria. The mean age of participants was 32.96 ± 9.47 years. The participants were from 16 different provinces of Iran, mainly from Gilan (n = 120, 49.4 per cent), Tehran (n = 63, 25.9 per cent), Alborz (n = 12, 4.9 per cent), Esfahan (n = 11, 4.5 per cent) and Mazandaran (n = 11, 4.5 per cent). These provinces were among the first provinces of the country to be affected by Covid-19.27 One-hundred and fifty-five (63.8 per cent) participants were female, and 54 (22.2 per cent) reported they were smokers. At the first follow up, 139 (57.2 per cent) participants had not recovered completely. Of this group, 130 (93.5 per cent) participants were reached in the second follow up.

Of 243 participants, 215 (88.5 per cent) reported total anosmia at the onset of the olfactory impairment. None of the responders reported any Covid-19 or sinonasal signs and symptoms in the original online survey. However, at the interview, 175 responders (72 per cent) reported mild symptoms: 153 responders (59.1 per cent) reported at least one of the Covid-19 symptoms and 66 responders (27.2 per cent) reported at least one of the rhinological symptoms. Loss of smell (with or without taste dysfunction) was reported as the first symptom by 119 participants (49 per cent) and as the sole symptom by 68 participants (28 per cent). None of the participants had undergone real-time polymerase chain reaction testing or had been evaluated by a computed tomography scan of the chest. Ten participants (4.1 per cent) reported Covid-19 diagnosis, and 77 participants (31.8 per cent) reported new onset loss of smell in at least one family member living at the same house. Accompanying symptoms are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The distribution of existing symptoms of participants

| Signs and symptoms | Total (n (%)) |

|---|---|

| Coronavirus 19 symptoms | 153 (59.1) |

| – Headache | 63 (24.7) |

| – Myalgia | 71 (27.4) |

| – Fever | 55 (21.9) |

| – Cough | 50 (19.3) |

| – Sore throat | 44 (17) |

| – Dyspnoea | 20 (7.7) |

| – Diarrhoea | 20 (7.7) |

| – Nausea or vomiting | 7 (2.7) |

| Rhinological symptoms | 66 (27.2) |

| – Rhinorrhoea | 47 (18.2) |

| – Sneeze | 34 (13.2) |

| – Nasal congestion | 16 (6.2) |

| – Nasal thick discharge | 2 (0.8) |

| – Need to blow the nose | 7 (2.9) |

Follow-up duration and final recovery rates

The mean total follow-up duration was 111.39 ± 59.34 days (median: 151, mode: 47, range: 26–203 days). The first interview was completed after a mean of 47.95 ± 12.44 days after the onset of smell loss (median: 46, mode: 40, range: 26–91 days).

At the first telephone interview, 104 patients (40.3 per cent) self-reported complete recovery. From the remaining 139 participants, 130 could be followed up with the second interview after a mean of 165.99 ± 9.34 days after the onset of their smell loss (median: 166, mode: 169, range: 142–203).

At the end of the study, those who had not completely recovered were followed for a mean of 149.38 ± 41.25 in ‘partial recovery’ (median: 164, mode: 166, range: 38–203) and 163.75 ± 10.81 in ‘no recovery’ groups (median: 161, mode: 154, range: 154–179). Finally, 239 participants (98.3 per cent) reported improvement: 173 (71.2 per cent) reported complete recovery and 66 (27.1 per cent) reported partial recovery. Mild, moderate and severe hyposmia was reported by 45 (18.5 per cent), 21 (8.6 per cent) and 4 (1.6 per cent) patients, respectively. No one reported anosmia at the last follow up.

Factors influencing complete recovery

The mean age of patients with and without complete recovery was 33.16 ± 10.24 and 32.48 ± 7.34 years, respectively (p = 0.614). Complete recovery was reported significantly more frequently in the patients with a family history of recent smell impairments (80.5 per cent (n = 62) vs 67.1 per cent (n = 110); p = 0.031) and less in those who reported fever as an accompanying symptom (58.3 per cent (n = 28) vs 74.6 per cent (n = 144); p = 0.026). Furthermore, the odds of complete recovery in patients without fever were 2.10 times higher in comparison with patients with fever (95 per cent confidence interval (CI): 1.08–4.07). There were no significant relationships between other symptoms and complete recovery. The rates of complete recovery were not significantly different between participants with rhinological symptoms, Covid-19 symptoms or those with isolated smell loss.

Duration of smell loss and predictive factors

The smell loss was self-reported to last for a mean of 32.54 ± 31.48 days (median: 21, mode: 30, range: 3–210) until complete recovery. Complete recovery of smell loss within the mean follow up of 111 days in 234 responders who could be reached at the last follow up showed the rate of improvement to be 56.2, 70.1, 71.5 and 74.7 per cent at 50, 100, 150 and 200 days following onset of smell loss, respectively (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier estimates showing the rate of regaining complete recovery (percentage) during the follow-up time.

In order to evaluate the factors influencing the duration of the smell loss, completely recovered participants were divided into three groups based on the first and third quartile of the time to recovery: rapid recovery (1–10 days), moderate recovery (11–45 days) and delayed recovery (more than 45 days). Rapidly recovered participants were significantly younger compared with the delayed recovery participants (31.3 ± 8.69 vs 35.55 ± 9.43; p = 0.031). Patients with smell loss as the sole symptom reported early recovery significantly more frequently compared with those who had any Covid-19 or sinonasal symptoms (88.7 per cent (n = 47) vs 73.1 per cent (n = 87); p = 0.037).

Although the prevalence of nasal congestion, headache, nausea or vomiting, and diarrhoea increased significantly in those who had a longer recovery period (Table 2), there was a statistically significant relationship only between diarrhoea and delayed recovery in the multiple logistic models (odds ratio = 4.65; p = 0.031; Table 3). However, the percentage of the patients with at least one rhinological symptom who had a delayed recovery was significantly higher (41.7 per cent (n = 10) vs 18.9 per cent (n = 28); p = 0.020, odds ratio = 3.06, 95 per cent CI = 1.13–5.19).

Table 2.

The association between symptoms and time to recovery

| Symptom | Time to complete recovery | P-value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–10 days (n (%))* | 11–45 days (n (%))† | >45 days (n (%))‡ | |||

| Headache | |||||

| – With | 8 (18.2) | 21 (47.7) | 15 (34.1) | 0.043 | 2.36 (1.09–5.10) |

| – Without | 42 (32.8) | 63 (49.2) | 23 (18) | ||

| Diarrhoea | |||||

| – With | 1 (10) | 3 (30) | 6 (60) | 0.011 | 5.95 (1.61–22.73) |

| – Without | 49 (30.4) | 80 (49.7) | 32 (19.9) | ||

| Nausea or vomiting | |||||

| – With | 0 | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | 0.016 | 7.69 (1.5–43.48) |

| – Without | 50 (30.3) | 81 (49.1) | 34 (20.6) | ||

| Nasal congestion | |||||

| – With | 1 (10) | 4 (40) | 5 (50) | 0.04 | 3.88 (1.06–14.29) |

| – Without | 49 (30.4) | 79 (49.1) | 33 (20.5) | ||

Odds ratios show the odds of delayed complete recovery versus rapid or moderate complete recovery. *n = 50; †n = 84; ‡n = 38. CI = confidence interval

Table 3.

The multiple logistic models for assessing the association between mentioned symptoms with later recovery

| Symptom | Odds ratio | Standard error (beta) | P-value | 95% CI for odds ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Diarrhoea | 4.65 | 0.71 | 0.031 | 1.15 | 18.87 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 3.85 | 0.97 | 0.163 | 0.58 | 25.64 |

| Nasal congestion | 2.46 | 0.75 | 0.229 | 0.57 | 10.75 |

| Headache | 1.70 | 0.44 | 0.229 | 0.72 | 4.03 |

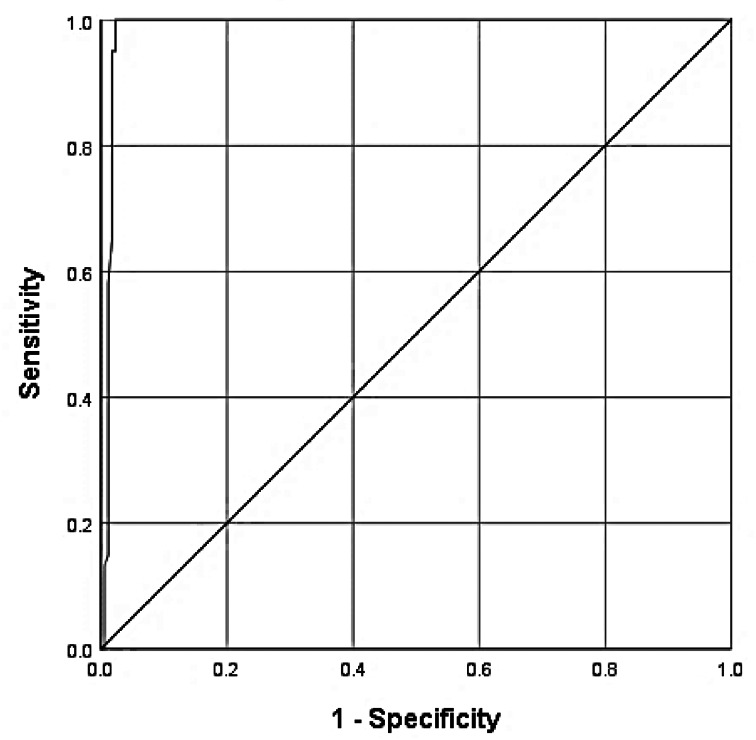

The receiver operating characteristic curve was used to classify the patients according to gaining complete recovery, considering the time passed from the onset of the smell loss. It showed that day 131 after the onset of olfactory dysfunction was the best cut-off for predicting that participants would not gain complete recovery (100 per cent sensitivity and 97.7 per cent specificity). The area under the receiver operating characteristic was 0.98 (95 per cent CI: 0.97–100; Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

The receiver operating characteristic curve to assess the efficacy of using the time passed from the onset of smell loss to predict the probability of not regaining complete recovery.

Discussion

This study was carried out on patients with sudden smell loss that happened during the Covid-19 pandemic and who reported mild Covid-19 or rhinological symptoms or no accompanying symptoms at all. Although 98.3 per cent of participants ultimately reported some improvement, the rate of complete recovery reported after at least 4 months of follow up was 71.2 per cent. Although no one reported anosmia, 1.6 per cent of respondents still complained of severe hyposmia, and 8.6 per cent reported moderate hyposmia at the end of the study.

The reported chance of recovery in routinely encountered post-viral olfactory loss ranged from 32 to 67 per cent, and around 20 per cent of patients did not recover after 1 year of viral infection.3,28 A review of articles published from 1 April to 31 October 2020 and focusing on the rate of recovery in confirmed cases of Covid-19 was carried out (Table 4).29–67 In the confirmed Covid-19 patients, the reported rates of complete recovery varied greatly (4 to 96 per cent for a 1-month follow up and 63 to 91.4 per cent for a 2-month follow up).29,52,57,64 The recovery rates for follow up of 3 and 6 months were reported to be 85.3 per cent and 86 per cent, respectively.49,65 It should be emphasised that because Covid-19 had not been confirmed by polymerase chain reaction in our patients, they were considered to be probable cases of Covid-19 according to WHO criteria. Their rate of complete recovery of smell loss was more similar to the rate of recovery of Covid-19 cases compared with other post-viral olfactory impairment. Interestingly, even patients who reported isolated smell loss self-reported a complete recovery rate of 77.9 per cent (in a mean follow-up time of 3.3 months which lasted for a mean of 26 ± 25.12 days), which is well above the reported rate of recovery for post-viral olfactory impairment. These patients even showed a faster recovery period compared with the others.

Table 4.

A review of the studies on olfactory dysfunction in Covid-19 which focused on smell loss recovery rate and duration

| Authors | Country | Followed cases with OD (n) | Covid-19 status | Follow-up duration | Method of assessment of OD | Recovery rate (%) | Time to recovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lechien et al.29 | Europe | 357 | Positive | Mean ± SD of 9.2 ± 6.2 days | Subjective | 44 early recovery | 96.6% in <15 days |

| Yan et al.12 | USA | 40 | Positive | <2 weeks | Subjective | 72.5 resolution | 76.52% in <15 days |

| Klopfenstein et al.30 | France | 54 | Positive | 28 days | Subjective | 98 recovery | 81% <2 weeks |

| Beltrán-Corbellini et al.31 | Spain | 31 smell/taste disorders | Positive | Not reported | Subjective | 40 complete recovery & 16.7 partial recovery | Mean ± SD of 7.4 ± 2.3 days for complete recovery & 9.1 ± 3.6 days for partial recovery |

| Vaira et al.32 | Italy | 53 smell/taste disorders | Positive | Mean of 19.3 days | Subjective & objective | Subjective evaluation: 66 complete recovery. Objective evaluation: 13.2 complete recovery | 54.28% in <5 days |

| Lee et al.33 | Korea | 232 | Positive | Maximum of 40 days | Subjective | 94% recovery in the first 35 days | Median of 7 days & most of them within 3 weeks |

| Hopkins et al.34 | UK | 382 | 80% positive of 15 tested cases | >4 weeks | Subjective | 71 | 75% took more than 4 weeks from the onset |

| Vaira et al.35 | Italy | 225 | Positive | Mean ± SD of 14.8 ± 7.4 days | Subjective & objective | Subjective evaluation: 31.3 regression. Objective evaluation: 9.3 complete recovery | Most took 10 days, then reached a plateau |

| Lechien et al.36 | Belgium | 86 | Positive with RT-PCR or IgM, IgG | Mean ± SD of 18 ± 11 days | Subjective & objective | Subjective evaluation: 0 complete recovery. Objective evaluation: 38.3 normosmia. | Mean ± SD of 17 ± 11 days for normosmics |

| Kosugi et al.37 | Brazil | 145 | Positive | Median of 31 days (range, 12–39) | Subjective | 52.6 complete recovery & 33.6 partial recovery | 15 days |

| Dell'Era et al.38 | Italy | 237 | Positive | Median of 23 days | Subjective | 62.9 complete recovery | Median of 10 days (range, 1–25 days) |

| Chung et al.39 | China | 6 patients subjectively evaluated | Positive | 14 days | Subjective | 50 | Not reported |

| Chung et al.39 | China | 6 patients objectively evaluated | Positive | 7–9 days | Objective | 66.6 | Not reported |

| Paderno et al.40 | Italy | 283 | Positive | In-patients: mean ± SD of 15.9 ± 6.7 (range, 1–45) days; out-patients: mean ± SD of 20.9 ± 7.4 (range, 6–45) days | Subjective | 52 complete recovery | Mean ± SD of 9 ± 5 days |

| Freni et al.41 | Italy | 46 | Positive | Mean ± SD of 49.7 ± 18.9 days | Subjective | 82 resolution | 5–8 days in 56% of patients |

| Sakalli et al.42 | Turkey | 88 | Positive | Mean ± SD of 4.3 ± 3.2 days (range, 1–11) | Subjective | 22.7 complete recovery & 55.7 partial recovery | Mean ± SD of 8.02 ± 6.41 days |

| Cervilla et al.43 | Spain | 44 | Positive | 1 month | Objective | 78 resolution | 77% in >15 days |

| Paderno et al.20 | Italy | 126 | Positive | Mean ± SD of 37 ± 9 days | Subjective | 87 resolution | 75.5% in <20 days |

| Gorzkowski et al.44 | France | 136 | Positive | Mean of 26 days | Subjective | 51.43 complete recovery | Recovery started between days 14 and 15 days in 78.4% |

| Boscolo-Rizzo et al.45 | Italy | 113 | Positive | 4 weeks | Subjective | 48.7 complete recovery & 40.7 partial recovery | Mean of 11.2 days |

| Salmon Ceron et al.46 | France | 48 | Positive | Mean ± SD of 15 ± 3 days | Subjective | 27.1 complete recovery & 72.9 partial recovery | Not reported |

| Jalessi et al.47 | Iran | 22 | Positive | Maximum 21 days | Subjective | 95.45 complete recovery | Mean ± SD of 10.73 ± 8.26 days |

| D'Ascanio et al.48 | Italy | 7 in-patients and 19 out-patients | Positive | By 30 days | Subjective | 85.7 resolution for in-patients & 84.3 resolution for out-patients | More than 5 days |

| Parente-Arias et al.49 | Spain | 75 | Positive | Mean ± SD of 100.5 ± 3.3 days (range, 91–108) | Subjective | 100 improvement & 85.3 complete recovery | Mean ± SD of 17.7 ± 8.9 days. 55.2% of them in the first 12 days |

| Barillari et al.50 | Italy | 207 | Positive and perhaps untested. | Mean ± SD of 11.6 ± 7.4 days | Subjective | 61.9 recovery | 1–15 days, 60% in <9 days |

| Fjaeldstad51 | Denmark | 100 | 42% positive and 58% untested | Mean of 33.5 days | Subjective | 44 complete recovery for smell loss | Mean of 15.1 and 14.9 days for positive and untested, respectively |

| Le Bon et al.52 | Belgium | 72 | Positive with RT-PCR or IgM, IgG | Mean of 37 days | Subjective & objective | 4 complete recovery 63 normosmic | A mean of 12 (range, 3–47) days |

| Spadera et al.53 | Italy | 180 | 89.6% of tested cases were positive | Not reported | Subjective | 6.11 complete recovery | 2–10 days |

| Moein et al.54 | Iran | 82 | Positive | Maximum of 8 weeks | Objective | 63 normosmia | Not reported |

| Klopfenstein et al.55 | France | 37 | Positive | Maximum of 28 days | Subjective | 99.97 recovery | Mean ± SD of 7.4 ± 5 days |

| Cocco et al.56 | Italy | 78 | Positive | Mean ± SD of 46.1 ± 19 days | Subjective | 51.3 smell recovery | Within 20 days |

| Vaira et al57 | Italy | 117 smell/taste disorders | Positive | Maximum of 60 days | Objective | 91.4 recovery | Mainly regressed within 30 days |

| Cho et al.58 | China | 39 | Positive | 4–6 weeks | Subjective | 71.8 complete recovery | Mean ± SD of 10.3 ± 8.1 days |

| Rojas-Lechuga et al.18 | Spain | 138 | Positive | Not reported | Subjective | 37.67 recovery | Median of 4, 6 and 7 days for mild, moderate and severe smell loss, respectively |

| Brandão Neto et al.59 | Brazil | 143 | Positive | Median 76 days | Subjective | 53.8 complete recovery & 44.7 partial recovery | Not reported |

| Chiesa-Estomba et al.60 | France | 751 | Positive with PCR or serology | Mean ± SD of 47 ± 7 days | Subjective | 49 complete recovery & 14 partial recovery | Mean ± SD of 10 ± 6 days for complete recovery & 12 ± 8 days for partial recovery |

| Amer et al.19 | Egypt | 96 | Positive | 1 month | Subjective | 33.3 complete recovery & 41.7 partial recovery | Mean of 17 days for complete recovery & mean of 11 days for partial recovery |

| Hao Lv et al.16 | China | 39 | Positive | Not reported | Subjective | 89.7 complete recovery & 10.2 partial recovery | >4 weeks in 51.4% |

| Karimi-Galougah et al.61 | Iran | 76 | Positive | 2 weeks | Subjective | 30.3 complete recovery & 44.7 partial recovery | Not reported |

| Iannuzzi et al.62 | Italy | 30 | Positive | 60 days | Subjective & objective | 73.3 normosmics | Not reported |

| Konstantinidis et al.63 | Greece | 30 | Positive | 4 weeks post-diagnosis | Subjective | 63.3 complete recovery & 36.6 partial recovery | Not reported |

| Panda et al.64 | India | 68 | Positive | 4 weeks | Subjective | 96 complete recovery | More than half by 2 weeks |

| Klein et al.65 | Israel | 84 | Positive | Maximum of 6 months | Subjective | 86 recovery | Mean ± SD of 18.9 ± 19.7 days, durations censored at 60 days |

| Schönegger et al.66 | Austria | 3 | Positive | 11–30 days from the first examination followed by 3 weeks’ follow up | Objective | 0 complete recovery & 33 partial recovery | Even after 30 to 50 days, patients still suffered from objective smell and taste disorders |

| Al-Zaidi et al.67 | Iraq | 58 | 20% positive, others untested | 1 month at least | Subjective | 39.66 recovery | 1–3 weeks, mainly in <1 week |

Covid-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; OD = olfactory dysfunction; SD = standard deviation; RT-PCR = real-time polymerase chain reaction; Ig = immunoglobulin

Various factors have been reported to influence the rate of recovery of smell loss in Covid-19 patients. The mean duration of olfactory impairment was reported to be 8 to 9 days in a pooled analysis of 20 studies.5 In our study, the duration of smell loss was significantly shorter in those with lower age and those who reported no additional symptoms besides the smell loss. There is a controversy in the reported effect of age on the duration of smell loss in Covid-19. Although Levinson et al.68 reported a longer duration of smell loss in patients aged over 40 years, patients with severe loss of smell who recover later have been reported to be younger in 2 studies.17,18 In a study by Fjaeldstad,51 with a similar methodology and study population to this study (online survey for out-patients with a mean age of 39.4 years who were mainly without confirmation for Covid-19), there was no significant effect of age on the time of recovery or recovery rates. As transmembrane serine protease 2 expression is reported to increase with older age, this may explain the negative effect of older age on the recovery of the sense of smell in the patients.69

The duration of smell loss was significantly longer in the patients who reported nasal congestion or any rhinological symptoms. Nasal congestion has been shown to be associated with a slow resolution and lower recovery rate.20,44 In the present study, nasal congestion did not affect the final complete recovery rates, but it slowed down the process of smell recovery. Only 10 per cent of the population with nasal congestion completely recovered within the first 10 days, and a report of rhinological symptoms increased the odds of the late recovery (complete recovery after 45 days) by 3 times. This may be a reflection of the conductive component effect (mucosal oedema) on the suggested mechanism of smell impairment.47,70,71 However, an increased level of inflammation, induced by pre-existing rhinitis, may also be responsible.

Nasal goblet (secretory) cells and ciliated cells in the epithelium of respiratory and gastrointestinal systems have shown the highest angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 expression.72 The exact mechanism of diarrhoea is still unclear, and any correlation between olfactory dysfunction and gastrointestinal symptoms has not been reported previously.73 However, diarrhoea has been shown to be correlated with more severe systemic inflammation in Covid-19 patients.74 It has also been considered as a risk factor for a more severe and poor prognosis course of the disease in several studies.75–77 At the last follow up, only 50 per cent (10 out of 20) of our participants with diarrhoea reported complete recovery, and the patients with diarrhoea had a 4.65 fold increased risk for delayed recovery.

The present study demonstrated that although improvement of smell loss may happen with longer follow up, the chance of complete recovery after 131 days from the onset of smell loss dramatically decreases (100 per cent sensitive and 97.7 per cent specific). Total recovery was shown to be significantly related to a short time from the onset of smell loss to the onset of recovery.44 Vaira et al.32 also emphasised the role of time passed since the clinical onset in improvement or total recovery.

A lower complete recovery rate and a longer duration to complete recovery was shown in this study compared with some of the previous studies, perhaps because of the predominantly female population, cases with severe loss of smell at the beginning and the method of the patient selection. In the present study, the majority of the participants were anosmic (88.5 per cent), and the remaining 11.5 per cent were reported to be severely hyposmic. The severity of smell loss has been reported to play a role in the prognosis. Longer recovery duration has been reported for patients with severe loss of smell compared with patients with milder impairment.17,18 Cases with severe smell loss in a study by Izquierdo-Domínguez et al. were younger, predominantly female and with a lower rate of pneumonia.17 Similarly, anosmia was found as a risk factor for later recovery.19,20 On the contrary, in a study by Paolo there was no significant difference in the time of resolution between hyposmic or anosmic patients.78

-

•

Various recovery rates have been reported for sudden unexplained anosmia encountered during the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic

-

•

Smell loss can be the prominent or sole symptom of Covid-19, although other viruses can induce olfactory dysfunction

-

•

After a mean of 5.5 months, the rate of improvement, complete recovery, and moderate or severe hyposmia were 98.3, 71.2 and 10 per cent, respectively

-

•

Complete recovery was associated positively with recent smell loss in at least one family member living with the patient and negatively with fever

-

•

Younger age and isolated smell loss were associated with a rapid recovery, and rhinological and gastrointestinal symptoms were associated with a slow recovery

-

•

After 131 days from the smell loss onset, the chance of regaining complete recovery dramatically decreased

A study by Paderno et al. discussed that women self-report recovery after a longer duration than men.20 Around 64 per cent of the population in our study was female, which may explain why less than 30 per cent of completely recovered patients had a duration of fewer than 9 days. However, this study did not show any significant differences in the rate of recovery between the sexes.

Limitations

In this study, the included participants had subtle or no Covid-19 symptoms and had not been tested by real-time polymerase chain reaction test. Therefore, definite allocation of the smell loss to Covid-19 or routine post-viral olfactory impairment was impossible, which may be considered as a significant limitation. The smell loss was self-assessed by an ordinal scale that may have limited correlation with more objective measures.79,80 In addition, we were unable to confirm self-reported recovery rates with psychophysical testing because of low compliance of paucisymptomatic participants for in-person attendance in the hospital for the tests during the pandemic.

Although the online surveys facilitate collecting information with minimal burden on healthcare personnel, they are prone to some biases. The results of this study show that subtle symptoms may not be reported properly in an online survey. This limitation was overcome by reconfirmation through telephone interview; however, it was still prone to recall bias or over-reporting because of prompting by the interviewer. On the other hand, in this study, in 50 per cent of the cases, a range of 14–28 days had passed from the initial loss of smell to their participation. This data shows a significant number of our participants were still suffering from smell loss after at least two weeks, and that was the possible reason they found the online survey in their searches and were more willing to participate. In other words, some patients who had rapidly recovered may not have participated.

Conclusion

Because of the high number of patients with Covid-19, the considerable prevalence of anosmia among the affected population and the huge negative impact of anosmia on quality of life, it is important to inform patients about favourable prognosis. However, a dramatic decrease in the rate of complete recovery happens after four months from the onset of smell loss, which may necessitate considering any optional treatments to start before this deadline. Although our patients were not definite cases of Covid-19 by WHO criteria, patients with smell loss as the sole symptom recovered significantly faster, whereas patients with rhinological or gastrointestinal symptoms may have a longer recovery period.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Ibekwe TS, Fasunla AJ, Orimadegun AE. Systematic review and meta-analysis of smell and taste disorders in COVID-19. OTO Open 2020;4:1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Global surveillance for COVID-19 caused by human infection with COVID-19 virus: interim guidance. In: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331506 [6 March 2020]

- 3.Hopkins C, Surda P, Kumar N. Presentation of new onset anosmia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rhinology 2020;58:295–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mao L, Wang M, Chen S, He Q, Chang J, Hong C et al. Neurological manifestations of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective case series study. JAMA Neurol 2020;77:683–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Bartheld CS, Hagen MM, Butowt R. Prevalence of chemosensory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis reveals significant ethnic differences. ACS Chem Neurosci 2020;11:2944–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pang KW, Chee J, Subramaniam S, Ng CL. Frequency and clinical utility of olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2020;20:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. (2020). Public health surveillance for COVID-19: interim guidance. In: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/333752 [7 August 2020]

- 8.Agyeman AA, Chin KL, Landersdorfer CB, Liew D, Ofori-Asenso R. Smell and taste dysfunction in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc 2020;95:1621–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Printza A, Constantinidis J. The role of self-reported smell and taste disorders in suspected COVID-19. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2020;277:2625–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tong JY, Wong A, Zhu D, Fastenberg JH, Tham T. The prevalence of olfactory and gustatory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020;163:3–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foster KJ, Jauregui E, Tajudeen B, Bishehsari F, Mahdavinia M. Smell loss is a prognostic factor for lower severity of COVID-19. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2020;125:481–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan CH, Faraji F, Prajapati DP, Ostrander BT, DeConde AS. Self-reported olfactory loss associates with outpatient clinical course in COVID-19. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2020;10:821–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mullol J, Alobid I, Mariño-Sánchez F, Izquierdo-Domínguez A, Marin C, Klimek L et al. The loss of smell and taste in the covid-19 outbreak: a tale of many countries. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2020;20:1–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meng X, Deng Y, Dai Z, Meng Z. COVID-19 and anosmia: a review based on up-to-date knowledge. Am J Otolaryngol 2020;41:102581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welge-Lüssen A, Wolfensberger M. Olfactory disorders following upper respiratory tract infections. Adv Otorhinolaryngol 2006;63:125–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lv H, Zhang W, Zhu Z, Xiong Q, Xiang R, Wang Y et al. Prevalence and recovery time of olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Int J Infect Dis 2020;100:507–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Izquierdo-Domínguez A, Rojas-Lechuga M, Chiesa-Estomba C, Calvo-Henríquez C, Ninchritz-Becerra E, Soriano-Reixach M et al. Smell and taste dysfunctions in COVID-19 are associated with younger age in ambulatory settings-a multicenter cross-sectional study. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2020;30:346–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rojas-Lechuga MJ, Izquierdo-Domínguez A, Chiesa-Estomba C, Calvo-Henríquez C, Villarreal IM, Cuesta-Chasco G et al. Chemosensory dysfunction in COVID-19 out-patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2021;278:695–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amer MA, El-Sherif HS, Abdel-Hamid AS, El-Zayat S. Early recovery patterns of olfactory disorders in COVID-19 patients; a clinical cohort study. Am J Otolaryngol 2020:41;102725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paderno A, Mattavelli D, Rampinelli V, Grammatica A, Raffetti E, Tomasoni M et al. Olfactory and gustatory outcomes in COVID-19: a prospective evaluation in nonhospitalized subjects. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020;163:1144–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. Laboratory testing strategy recommendations for COVID-19: interim guidance. In: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331509 [21 March 2020]

- 22.Bagheri SH, Asghari A, Farhadi M, Shamshiri AR, Kabir A, Kamrava SK et al. Coincidence of COVID-19 epidemic and olfactory dysfunction outbreak in Iran. Med J Islam Repub Iran 2020;34:446–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seok J, Shim YJ, Rhee C-S, Kim J-W. Correlation between olfactory severity ratings based on olfactory function test scores and self-reported severity rating of olfactory loss. Acta Otolaryngol 2017;137:750–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campiglio L, Priori A. Neurological symptoms in acute COVID-19 infected patients: a survey among Italian physicians. PLoS One 2020;15:e0238159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jalessi M, Farhadi M, Kamrava SK, Amintehran E, Asghari A, Hemami MR et al. The reliability and validity of the persian version of sinonasal outcome test 22 (snot 22) questionnaires. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2013;15:404–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeConde AS, Mace JC, Bodner T, Hwang PH, Rudmik L, Soler ZM, et al. SNOT-22 quality of life domains differentially predict treatment modality selection in chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2014;4:972–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Committee on COVID-19 Epidemiology, Ministry of Health and Medical Education, IR Iran. Daily Situation Report on Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Iran; March 14, 2020. Arch Acad Emerg Med 2020;8:e24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee DY, Lee WH, Wee JH, Kim J-W. Prognosis of postviral olfactory loss: follow-up study for longer than one year. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2014;28:419–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, De Siati DR, Horoi M, Le Bon SD, Rodriguez A et al. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2020;277:2251–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klopfenstein T, Toko L, Royer PY, Lepiller Q, Gendrin V et al. Features of anosmia in COVID-19. Med Mal Infect 2020;50:436–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beltrán-Corbellini A, Chico-García JL, Martínez-Poles J, Rodríguez-Jorge F, Natera-Villalba E, Gómez-Corral J et al. Acute-onset smell and taste disorders in the context of COVID-19: a pilot multicentre polymerase chain reaction based case–control study. Eur J Neurol 2020;27:1738–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vaira LA, Deiana G, Fois AG, Pirina P, Madeddu G, De Vito A et al. Objective evaluation of anosmia and ageusia in COVID-19 patients: single-center experience on 72 cases. Head Neck 2020;42:1252–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee Y, Min P, Lee S, Kim SW. Prevalence and duration of acute loss of smell or taste in COVID-19 patients. J Korean Med Sci 2020;35:e174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hopkins C, Surda P, Whitehead E, Kumar BN. Early recovery following new onset anosmia during the COVID-19 pandemic - an observational cohort study. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020;49:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vaira LA, Hopkins C, Salzano G, Petrocelli M, Melis A, Cucurullo M et al. Olfactory, and gustatory function impairment in COVID-19 patients: Italian objective multicenter-study. Head Neck 2020;42:1560–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lechien JR, Cabaraux P, Chiesa-Estomba CM, Khalife M, Hans S, Calvo-Henriquez C et al. Objective olfactory evaluation of self-reported loss of smell in a case series of 86 COVID-19 patients. Head Neck 2020;42:1583–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kosugi EM, Lavinsky J, Romano FR, Fornazieri MA, Luz-Matsumoto GR, Lessa MM et al. Incomplete and late recovery of sudden olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2020;86:490–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dell'Era V, Farri F, Garzaro G, Gatto M, Aluffi Valletti P, Garzaro M. Smell and taste disorders during COVID-19 outbreak: cross-sectional study on 355 patients. Head Neck 2020;42:1591–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chung TWH, Sridhar S, Zhang AJ, Chan KH, Li HL, Wong FKC et al. olfactory dysfunction in coronavirus disease 2019 patients: observational cohort study and systematic review. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020;7:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paderno A, Schreiber A, Grammatica A, Raffetti E, Tomasoni M, Gualtieri T et al. Smell and taste alterations in COVID-19: a cross-sectional analysis of different cohorts. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2020;10:955–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Freni F, Meduri A, Gazia F, Nicastro V, Galletti C, Aragona P et al. Symptomatology in head and neck district in coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a possible neuroinvasive action of SARS-CoV-2. Am J Otolaryngol 2020;41:102612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sakalli E, Temirbekov D, Bayri E, Alis EE, Erdurak SC, Bayraktaroglu M. Ear nose throat-related symptoms with a focus on loss of smell and/or taste in COVID-19 patients. Am J Otolaryngol 2020;41:30–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cervilla MT, Gutierrez I, Romero M, Garcia-Gomez J. Research Square. Olfactory dysfunction quantified by olfactometry in patients with SARS-Cov-2 infection. 2020. In: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342429355_Olfactory_dysfunction_quantified_by_olfactometry_in_patients_with_SARS-Cov-2_infection [19 April 2021]

- 44.Gorzkowski V, Bevilacqua S, Charmillon A, Jankowski R, Gallet P, Rumeau C et al. Evolution of olfactory disorders in COVID-19 patients. Laryngoscope 2020;130:2667–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boscolo-Rizzo P, Borsetto D, Fabbris C, Spinato G, Frezza D, Menegaldo A et al. Evolution of altered sense of smell or taste in patients with mildly symptomatic COVID-19. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020;1:8–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salmon Ceron D, Bartier S, Hautefort C, Nguyen Y, Nevoux J, Hamel AL et al. Self-reported loss of smell without nasal obstruction to identify COVID-19. The multicenter Coranosmia cohort study. J Infect 2020;81:614–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jalessi M, Barati M, Rohani M, Amini E, Ourang A, Azad Z et al. Frequency and outcome of olfactory impairment and sinonasal involvement in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Neurol Sci 2020;41:2331–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.D'Ascanio L, Pandolfini M, Cingolani C, Latini G, Gradoni P, Capalbo M et al. Olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients: prevalence and prognosis for recovering sense of smell. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2021;164:82–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parente-Arias P, Barreira-Fernandez P, Quintana-Sanjuas A, Patiño-Castiñeira B. Recovery rate and factors associated with smell and taste disruption in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Am J Otolaryngol 2020;42:102648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barillari MR, Bastiani L, Lechien JR, Mannelli G, Molteni G, Cantarella G et al. A structural equation model to examine the clinical features of mild-to-moderate COVID - 19: a multicenter Italian study. J Med Virol 2021;93:983–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fjaeldstad AW. Prolonged complaint s of chemosensory loss after covid-19. Dan Med J 2020;67:1–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Le Bon SD, Pisarski N, Verbeke J, Prunier L, Cavelier G, Thill MP et al. Psychophysical evaluation of chemosensory functions 5 weeks after olfactory loss due to COVID-19: a prospective cohort study on 72 patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2021;278:101–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spadera L, Viola P, Pisani D, Scarpa A, Malanga D, Sorrentino G et al. Sudden olfactory loss as an early marker of COVID-19: a nationwide Italian survey. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2021;278:247–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moein ST, Hashemian SMR, Tabarsi P, Doty RL. Prevalence and reversibility of smell dysfunction measured psychophysically in a cohort of COVID-19 patients. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2020;10:1127–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Klopfenstein T, Zahra H, Kadiane-Oussou NJ, Lepiller Q, Royer PY, Toko L et al. New loss of smell and taste: uncommon symptoms in COVID-19 patients in Nord Franche-Comte cluster, France. Int J Infect Dis 2020;100:117–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cocco A, Amami P, Desai A, Voza A, Ferreli F, Albanese A. Neurological features in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients with smell and taste disorder. J Neurol 2020. Epub 2020 Aug 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vaira LA, Hopkins C, Petrocelli M, Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, Salzano G et al. Smell and taste recovery in coronavirus disease 2019 patients: a 60-day objective and prospective study. J Laryngol Otol 2020;134:703–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cho RHW, To ZWH, Yeung ZWC, Tso EYK, Fung KSC, Chau SKY et al. COVID-19 viral load in the severity of and recovery from olfactory and gustatory dysfunction. Laryngoscope 2020;130:2680–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brandão Neto D, Fornazieri MA, Dib C, Di Francesco RC, Doty RL, Voegels RL et al. Chemosensory dysfunction in COVID-19: prevalences, recovery rates, and clinical associations on a large Brazilian sample. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2021;164:512–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chiesa-Estomba CM, Lechien JR, Radulesco T, Michel J, Sowerby LJ, Hopkins C et al. Patterns of smell recovery in 751 patients affected by the COVID-19 outbreak. Eur J Neurol 2020;27:2318–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Karimi-Galougahi M, Safavi Naini A, Ghorbani J, Raad N, Raygani N. Emergence and evolution of olfactory and gustatory symptoms in patients with COVID-19 in the outpatient setting. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020. Epub 2020 Sep 28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Iannuzzi L, Salzo AE, Angarano G, Palmieri VO, Portincasa P, Saracino A et al. Gaining back what is lost: recovering the sense of smell in mild to moderate patients after COVID-19. Chem Senses 2020;45:875–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Konstantinidis I, Delides A, Tsakiropoulou E, Maragoudakis P, Sapounas S, Tsiodras S. Short-term follow-up of self-isolated COVID-19 patients with smell and taste dysfunction in greece: two phenotypes of recovery. Orl 2020;82:295–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Panda S, Mohamed A, Sikka K, Kanodia A, Sakthivel P, Thakar A et al. Otolaryngologic manifestation and long-term outcome in mild COVID-19: experience from a tertiary care centre in india. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020;73:1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Klein H, Asseo K, Karni N, Benjamini Y, Nir-Paz R, Muszkat M et al. Onset, duration, and persistence of taste and smell changes and other COVID-19 symptoms: longitudinal study in Israeli patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. Epub 2021 Feb 16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schönegger CM, Gietl S, Heinzle B, Freudenschuss K, Walder G. Smell and taste disorders in COVID-19 patients: objective testing and magnetic resonance imaging in five cases. SN Compr Clin Med 2020. Epub 2020 Oct 24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Al-Zaidi HMH, Badr HM Incidence and recovery of smell and taste dysfunction in COVID-19 positive patients. Egypt J Otolaryngol 2020;36:1–6 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Levinson R, Elbaz M, Ben-Ami R, Shasha D, Levinson T, Choshen G et al. Time course of anosmia and dysgeusia in patients with mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. Infect Dis (Lond) 2020;52:600–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bilinska K, Jakubowska P, Von Bartheld CS, Butowt R. Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 entry proteins, ACE2 and TMPRSS2, in cells of the olfactory epithelium: identification of cell types and trends with age. ACS Chem Neurosci 2020;11:1555–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Eliezer M, Hautefort C, Hamel A-L, Verillaud B, Herman P, Houdart E et al. Sudden and complete olfactory loss function as a possible symptom of COVID-19. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020;146:674–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brann DH, Tsukahara T, Weinreb C, Lipovsek M, Van den Berge K, Gong B, et al. Non-neuronal expression of SARS-CoV-2 entry genes in the olfactory system suggests mechanisms underlying COVID-19-associated anosmia. Sci Adv 2020;6:eabc5801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sungnak W, Huang N, Bécavin C, Berg M, Queen R, Litvinukova M et al. SARS-CoV-2 entry factors are highly expressed in nasal epithelial cells together with innate immune genes. Nat Med 2020;26:681–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.D'Amico F, Baumgart DC, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Diarrhea during COVID-19 infection: pathogenesis, epidemiology, prevention and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;18:1663–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Uzzan M, Soudan D, Peoc'h K, Weiss E, Corcos O, Treton X. Patients with COVID-19 present with low plasma citrulline concentrations that associate with systemic inflammation and gastrointestinal symptoms. Dig Liver Dis 2020;52:1104–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Guan W-j, Ni Z-y, Hu Y, Liang W-h, Ou C-q, He J-x et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1708–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jin X, Lian J-S, Hu J-H, Gao J, Zheng L, Zhang Y-M et al. Epidemiological, clinical and virological characteristics of 74 cases of coronavirus-infected disease 2019 (COVID-19) with gastrointestinal symptoms. Gut 2020;69:1002–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee I-C, Huo T-I, Huang Y-H. Gastrointestinal and liver manifestations in patients with COVID-19. J Chin Med Assoc 2020;83:521–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Paolo G. Does COVID-19 cause permanent damage to olfactory and gustatory function? Med Hypotheses 2020;143:110086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Whitcroft KL, Hummel T. Olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19: diagnosis and management. JAMA 2020;323:2512–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kamrava S, Jalessi M., GhalehBaghi S, Amini E, Alizadeh R, Rafiei F et al. Validity and reliability of Persian smell identification test. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol 2020;32:65–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]