Abstract

Background:

Physical distancing among healthcare workers (HCWs) is an essential strategy in preventing HCW-to-HCWs transmission of severe acute respiratory coronavirus virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

Objective:

To understand barriers to physical distancing among HCWs on an inpatient unit and identify strategies for improvement.

Design:

Qualitative study including observations and semistructured interviews conducted over 3 months.

Setting:

A non–COVID-19 adult general medical unit in an academic tertiary-care hospital.

Participants:

HCWs based on the unit.

Methods:

We performed a qualitative study in which we (1) observed HCW activities and proximity to each other on the unit during weekday shifts July–October 2020 and (2) conducted semi-structured interviews of HCWs to understand their experiences with and perspectives of physical distancing in the hospital. Qualitative data were coded based on a human-factors engineering model.

Results:

We completed 25 hours of observations and 20 HCW interviews. High-risk interactions often occurred during handoffs of care at shift changes and patient rounds, when HCWs gathered regularly in close proximity for at least 15 minutes. Identified barriers included spacing and availability of computers, the need to communicate confidential patient information, and the desire to maintain relationships at work.

Conclusions:

Physical distancing can be improved in hospitals by restructuring computer workstations, work rooms, and break rooms; applying visible cognitive aids; adapting shift times; and supporting rounds and meetings with virtual conferencing. Additional strategies to promote staff adherence to physical distancing include rewarding positive behaviors, having peer leaders model physical distancing, and encouraging additional safe avenues for social connection at a safe distance.

Physical distancing—staying at least 2 m (6 feet) away from others to reduce transmission risk—is a cornerstone of severe acute respiratory coronavirus virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission prevention.1 Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreaks among healthcare workers (HCWs) working on the same clinical unit have been reported related to distancing failures.2,3 Constraints related to the hospital work environment, such as educational conferences, administrative meetings, teaching, crowded clinical workrooms, rounds, signing out, and using call rooms, are situations in which maintaining physical distance can be challenging.4 However, little information on the barriers to and facilitators for physical distancing in a hospital unit using a systems approach is available.

Human factors engineering (HFE) focuses on understanding interactions among people in complex work systems.5 A HFE-informed approach could provide guidance on redesign of the healthcare work system to improve physical distancing among HCWs. The Systems Engineering in Patient Safety (SEIPS) model describes interactions between elements of a work system (here, a hospital unit), and their impact on processes (here, physical distancing), and outcomes such as SARS-CoV-2 transmission prevention.6 Elements of the work system include characteristics of the person (ie, an HCW), tools and technologies used, the organization (at the service, unit, or hospital level), physical environment, and tasks, within an external regulatory and cultural environment. Understanding how these work system elements interact to affect physical distancing on a hospital unit may facilitate physical distancing.

We undertook a qualitative study of HCWs in an inpatient non–COVID-19 medical unit to understand barriers to, facilitators of, and strategies for physical distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Understanding these factors could allow the redesign of the unit work system to facilitate physical distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic and future pandemics.

Methods

Setting and participants

The inpatient non–COVID-19 24-bed medical unit was in a tertiary-care academic medical center in Baltimore, Maryland, and was staffed by internal medicine resident physicians and nurses. At the time of the study, HCWs were required to wear surgical masks while in non–COVID-19 patient care areas, with the addition of face shields for patient interactions. HCWs were advised to remain 2 m apart from other HCWs, and room occupancy signage and floor decals indicating where HCWs could stand were available. The study was conducted from July 24 to October 19, 2020, when COVID-19 community cases rates ranged from 8 to 15 cases per 100,000 residents daily.7 The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Study design

We used 2 qualitative methods to identify barriers to, facilitators of, and strategies for physical distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: direct observations and semistructured interviews. Observations and interviews focused on physical distancing when HCWs were not directly interacting with patients.

Observations

An observation form was designed based on the unit map of common areas including nurses stations, breakrooms, and workrooms (Appendix 1 online). Patient rooms were excluded because the focus of the work was not on distancing among HCWs and patients. The forms focused on numbers and roles of observed HCWs, whether groups were 2 m apart, compliance with recommended personal protective equipment (PPE), tasks the HCWs were doing, tools the HCWs were using, and relative location of the HCWs during the interaction (eg, standing vs sitting; face-to-face vs opposite; or stationary vs moving). Observers also noted any perceived barriers, facilitators, and strategies for physical distancing.

Observations were performed by 1 of 3 observers (P.O., S.C.K., or A.C.S.) between July 29 and October 1, 2020. Each observation lasted 30–60 minutes. During each observation, every 5 minutes, observers would record all HCWs in their visual field on the electronic form. To better model HCW experiences, timing of observations were enriched for the likelihood of HCWs working in specific locations (eg, observing the nursing report room during shift change) and for weekdays when unit HCW density was highest. If 2 locations were within the same visual field, observers recorded observations for both locations.

Although unit leaders were informed of the observations and the study team presented the study at staff meetings, HCWs were not informed of particular days and times of observation. To learn how far 2 m (6 feet) was, observers visited the unit wearing monitors that blinked if the observers were <2 m from each other. Frequent discussions between observers ensured that all were filling forms out in a standard manner. Any observation forms with incomplete information were returned to observers for clarification.

Semistructured interviews

Our semistructured interview guide was based on the SEIPS model6 and also addressed perceptions of physical distancing in the hospital.

Semistructured HCW interviews were conducted by 2 investigators (P.O. and S.C.K.) via videoconference. Interviews occurred between July 24 and October 19, 2020, and each lasted for 20–40 minutes. Eligible HCWs included those primarily based on the participating unit, including resident and attending physicians, nurses, unit managers, physical therapists, clinical services representatives, transport staff, nutritionists, and unit associates. There were no advanced practice practitioners assigned to the clinical unit during the study period. HCWs were recruited through e-mails, flyers, and staff-meeting presentations. We performed purposive sampling to ensure capture of experiences from different HCW roles.8 Participants provided oral consent prior to the interview and were provided a $10 gift card as an incentive. Interviews were recorded and transcribed.

Independently, investigators (S.C.K., C.R., S.P., S.E.C., P.O., A.C.S., and A.B.S.) independently reviewed and coded the same 2 randomly selected transcripts. The study team compared their coded transcripts and developed the preliminary coding template. Two investigators (S.P. and S.C.K.) independently reviewed all transcripts, meeting after every 5 transcripts to compare their coding of the transcripts and determine if additional codes needed to be added. As additional codes were added, transcripts were rereviewed, and changes were applied retroactively.

Analysis

Observation data were presented as a descriptive analysis of physical distancing over a day shift for resident physicians or nurses (the 2 most frequently observed HCW roles). Observation data were categorized into 3 levels of risk for infection transmission: low risk (HCWs physically distancing and wearing masks appropriately), medium risk (HCWs not physically distancing for <15 minutes and wearing masks appropriately), and high risk (HCWs <2 m of each other for ≥15 minutes, or any inappropriate masking while not physically distancing). We summed the total number of HCWs observed in each 5-minute interval as well as total duration.

Directed content analysis of the interview transcripts was performed, focusing on barriers to, facilitators of, and strategies for physical distancing, guided by the SEIPS model.6 Interviews were conducted and coded until thematic saturation was reached.9 We compared key findings with prior interviews; if no new key findings were identified, thematic saturation was achieved. Triangulation between observations and interviews was applied to further contextualize the data.10 Themes presented included recurrent unifying concepts or statements.11 The analysis was conducted using NVivo version 12 Pro software (QSR International, Australia).

Results

We interviewed 20 HCWs of 90 potentially eligible HCWs; 16 were female and 11 were nurses (Table 1). We observed the unit for 25 hours on weekdays between 7:00 a.m. and 7:30 p.m. The most frequent locations for high-risk interactions were the nursing stations, hallways, and nurses’ report room during shift changes (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Interview Participants (N=20)

| Characteristic | Total (N= 20), No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex, female | 16 (80) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White | 7 (35) |

| Black | 6 (30) |

| Asian American | 4 (20) |

| >1 race | 3 (15) |

| Position | |

| Nurse | 11 (55) |

| Housestaff | 4 (20) |

| Manager or administrator | 1 (5) |

| Attending physician | 1 (5) |

| Physical therapist | 1 (5) |

| Dietician | 1 (5) |

| Transportation | 1 (5) |

| Time in position, median y (range) | 2.5 (1 mo–17 y) |

Table 2.

Frequency, Duration, and Risk Level of Interaction Among Observed Healthcare Workers

| Location | Low Risk, Minutes, No. of HCWsa |

Medium Risk, Minutes, No. of HCWsa |

High Risk, Minutes, No. of HCWsa |

No. and Time of Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing report room | 95, N = 34 | 55, N = 25 | 100, N = 57 | 6 (7:15 a.m.–8:05 a.m., 10:00 a.m.–11:35 a.m., 7:00 p.m.–7:35 p.m.); duration, 3.3 h |

| Nursing station 1 and hallway 1 | 415, N = 276 | 190, N = 80 | 215, N = 106 | 9 (7:00 a.m.–11:20 a.m., 6:00 p.m.–7:05 p.m.); duration, 9 h |

| Nursing station 2 and hallway 2 | 275, N = 115 | 100, N = 45 | 205, N = 97 | 6 (6:00 a.m.–7:05 a.m., 8:10 a.m.–9:15 a.m., 11:00 a.m.–1:05 p.m., 6:30 p.m.–7:30 p.m.); duration, 6.4 h |

| Housestaff team room | 55, N = 49 | 20, N = 21 | 15, N = 9 | 3 (9:00 a.m.–9:30 a.m., 11:40 a.m.–12:35 p.m.); duration, 1.3 h |

| Break room | 25, N = 7 | … | … | 2 (11:20 a.m.–12:05 p.m.); duration, 1 h |

| Medication rooms A and B, and supply room | 65, N = 20 | 40, N = 18 | … | 7 (8:05 a.m.–10:00 a.m., 12:30 p.m.–1:05 p.m., 2:45 p.m.–3:35 p.m., 5:50 p.m.–6:05 p.m.); duration, 3.8 h |

Note. HCW, healthcare worker.

HCWs were the total number of HCWs observed in these categories summed over each 5-minute interval.

Findings by HCW role

For nurses, shift change report was a source of high-risk interactions lasting 15–45 minutes (Appendix Fig. 1A online). Brief in-person communications among HCWs or using computers near HCWs were medium-risk interactions. Nurses were appropriately spaced during meals. Nurses spent up to 2 hours in close proximity to other HCWs over a shift.

For resident physicians, patient sign-out was a high-risk interaction due to sitting in close proximity, where high-risk activities were observed including eating without a mask <2 m apart for >15 minutes (Appendix Fig. 1B online). Morning patient rounds, where 4–6 resident physicians moved around the unit closely spaced for 90 minutes, and teaching rounds were also high risk. As strategies to facilitate physical distancing, we observed pharmacists and students joining rounds via videoconferencing, and residents and students waiting outside team rooms for their turn to present. Educational conferences were also considered high risk because resident physicians ate without masks <2 m apart, according to observations and interviews. Resident physicians were in close proximity to other HCWs for up to 6 hours during a shift.

Identified barriers

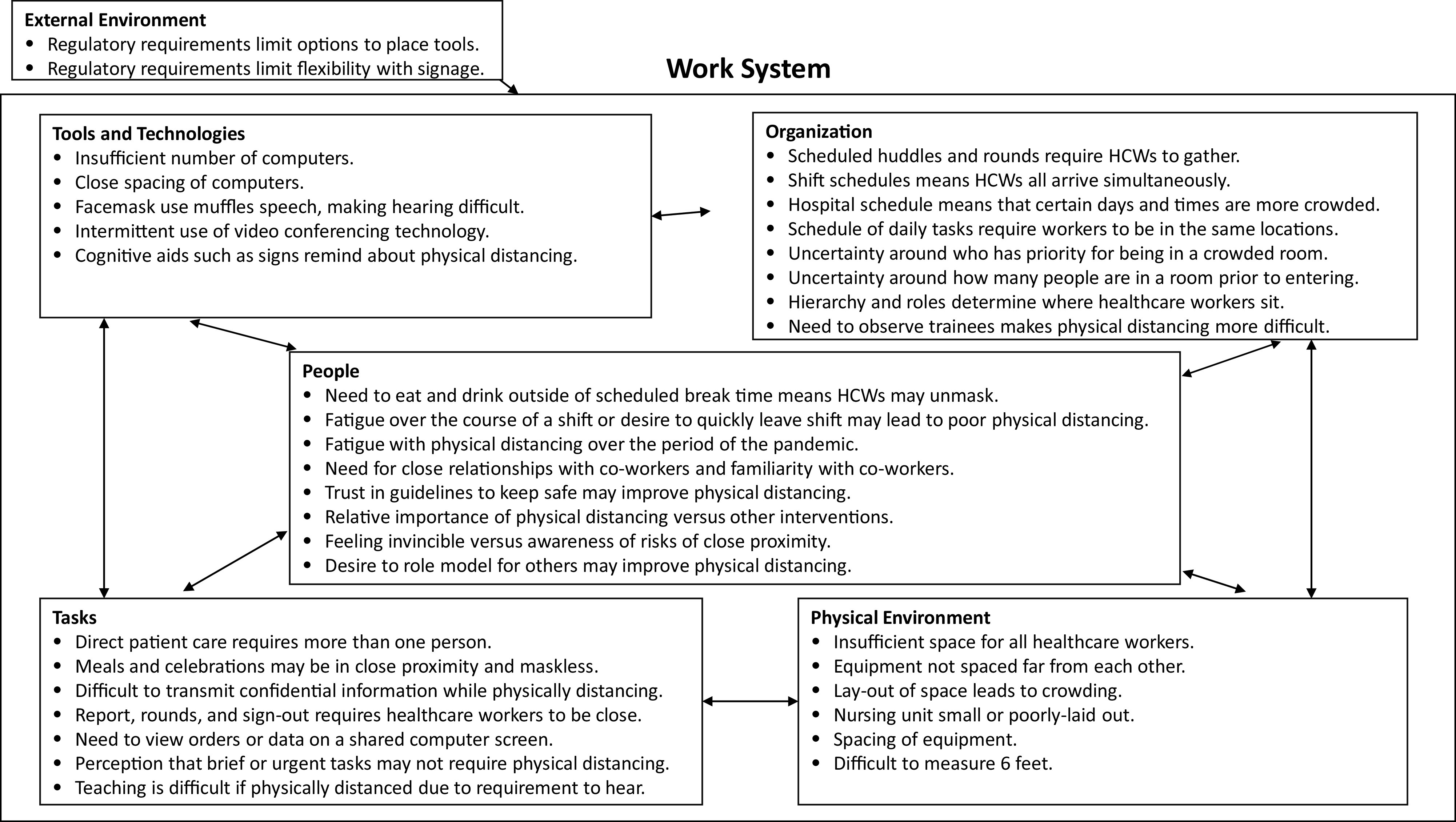

Based on the qualitative interviews and observations, we identified barriers to, facilitators of, and strategies for physical distancing. Using the SEIPS model6 (Fig. 1), data are presented using the characteristics of the unit’s work system: people (HCWs), the physical environment, the tasks HCWs need to perform, the tools and technologies used, and the organization of the service, unit, or hospital, in the context of an external regulatory and cultural environment (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Systems Engineering and Patient Safety (SEIPS) model6 as applied to physical distancing among healthcare workers in a non–COVID-19 acute-care medical unit.

Table 3.

Identified Barriers, Facilitators, Strategies and HCW Wishes to Optimizing Physical Distancing

| Work System Element | Barrier | Facilitators | Strategies and Wishes Described by Participants |

|---|---|---|---|

| People | • Need to eat and drink outside of break time • Fatigue at the end of a shift • Desire to quickly complete shift • Desire to have close connections with other HCWs or maintain friendships at work • Familiarity and comfort with coworkers may make HCWs believe physical distancing is not as important at work • Feeling of invincibility • Feelings about the importance of physical distancing compared with other precautions (eg, personal protective equipment) |

• Desire to do the right thing • Belief in the importance of physical distancing • Trust in physical distancing guidelines |

• Communication with others about need to physically distance • Increased recognition of staff and their efforts • A focus on rewards rather than punishments |

| Physical Environment | • Insufficient space for all HCWs • Insufficient spacing of computer workstations for all HCWs • Poor layout of room causes crowding • Storage of supplies needed at times of the day requires HCWs to gather to find supplies • Tables are small, making it difficult to spread out during meetings |

• More spacious areas | • Convert rarely used rooms to workspaces • Relocate or space out computers • Strict occupancy limits for rooms • Relocate meetings to larger spaces • Remove tables and chairs to prevent gathering |

| Tasks | • Need to provide confidential information • Communication and teaching requires close proximity to hear • Reporting, huddlings, and signing out require gathering • Patient care requires multiple HCWs at a time • Need to view data on a shared computer screen • Meals and celebrations may take multiple people • Space for eating was not a priority • The immediacy or urgency of a task takes priority • Brief tasks are perceived as not requiring physical distancing |

• Willingness to adjust workflows to promote physical distancing | • Spread out during reporting or signing out • Move talks or meetings online • Maintain disctance during meals • Have fewer people on rounds |

| Tools and Technologies | • Insufficient numbers or quality of computers or other tools necessary to perform work • Needing to share computers • Placement of computers prohibits efficient use • Masks muffle speech, making it difficult to hear • Video conferencing technology intended to allow others to join remotely requires members of a team to gather around 1 computer monitor |

• Video conferencing technology • Communication via electronic messaging applications or telephone |

• Phone-based reporting or signing off • More computers that are portable • Dedicated video conferencing room for team to remotely join • Remote patient monitoring • Additional plexiglass barriers • Video conferencing for bedside rounds • Cognitive aids such as floor stickers, room occupancy limitations, and signage • Frequent e-mailed reminders • Accessible internal web resources • Disabling computers, and more or higher quality computers |

| Organization | • Scheduled communications such as huddles require HCWs to gather • Many HCWs change shift at the same time, temporarily doubling the number of HCWs • Hospital workflow means that certain times of the day or days of the week have more HCWs • The workflow of the day requires tasks to occur in a certain order for many HCWs (eg, report or rounds, medication dispensing, meals, etc) • Unclear who has priority to be in a room • Unclear how many people are in a room before entering • Hierarchy determines where HCWs sit and whether they ask others to physically distance • Culture of bedside rounds |

• Time of day or week may be less busy • Role of leadership in encouraging physical distancing |

• Increased hospital-level recognition of staff and their efforts • Focus on rewards rather than punishments • Centralized meal program for staff • Importance of communication from administration • Staff member responsible for monitoring physical distancing • Changes to structure of huddles or report, such as one-on-one huddles • Changes to rounds including having fewer people participate • Hospital training on physical distancing |

| External Environment | • Requirements from regulatory agencies prohibit optimal placement of workstations or tools • Requirements from regulatory agencies prohibit signage or other cognitive aids |

• External societal pressures for physical distancing |

Note. HCW, healthcare worker.

Characteristics of people

In interviews, HCW characteristics influenced physical distancing. The desire to maintain friendships made physical distancing difficult, as a resident physician explained:

“We’re all friends in the hospital … so it’s hard to [physically distance]. … I think it’s a sense of camaraderie also to not social[ly] distance. People say things like … ‘Let’s do … a contraband hug or … illicit hug,’ and that’s … a sign of endearment.”

Comfort with coworkers also may mean that HCWs feel safer not physically distancing with coworkers, as another resident physician explained:

“I think we’re all very good friends, and I also think that with … staying … away from people outside of work, in work we tend to be more lax [with physical distancing] than strict just because … this is the only contact we have with the outside world a lot of times.”

Meanwhile, person-level facilitators to physical distancing included the desire to do the right thing and to role model, and belief in the importance of physical distancing.

Physical environment characteristics

We also investigated the role of the physical environment in physical distancing. The unit’s structure provided insufficient space to allow all HCWs to perform work while physically distancing, as noted in observations and interviews. A resident physician explained:

“So, we were told we should socially distance but there weren’t enough chairs in the offices. We were told to socially distance but the computers were not spaced such that we can do that. And so suddenly, … if there were 7 computers in the room, to socially distance we could only use three.”

We observed and HCWs described several strategies to modify the physical environment. They converted rarely used rooms into work spaces or break rooms, relocated meetings, and placed occupancy limits on rooms. HCWs also relocated, turned off, or spaced computers and removed tables and chairs to prevent gathering.

Task characteristics

In observations and interviews, tasks also affected physical distancing. Communicating confidential information (in informal communications as well as rounds, reporting, signing out, or huddling) was difficult from >2 m, especially while wearing masks. Discussing patients often also required reviewing data with another HCW on the same computer screen. This made physical distancing difficult, as one nutritionist explained:

“When we have students who come … and we have to … go over notes with them so we sit next to them for a period of time. … It’s kind of hard to keep that distancing when you’re working with them on the same computer.”

In addition, the immediacy or urgency of a task took priority, and brief tasks were perceived as not requiring physical distancing. Strategies included changing the unit’s workflow to make rounds, huddles, meetings, or educational sessions remote.

Tools and technologies characteristics

In observations and interviews, tools and technologies served as barriers and facilitators to physical distancing. Insufficient numbers or quality of computers or other tools necessary to perform work resulted in using computers near each other, as one resident physician explained:

“… you’re supposed to be sitting every other computer, but for us, sometimes the good computers are right next to each other. … So, some of the computers have two screens, which makes it a lot easier to multitask, and then there’s … one computer that … starts making very strange noises when you log in to it, so nobody likes that one. … And then there’s another computer that’s right next to a telephone that doesn’t work.”

Meanwhile, electronic messaging, videoconference, or telephone improved communication. Cognitive aids such as floor decals and signage also helped.

Organizational characteristics

Organizational factors impacted physical distancing, as noted in observations and interviews. Workflow barriers included scheduled communications that required HCWs to gather (eg, huddling, reporting, signing off, rounds, etc). In addition, many HCWs changed shift simultaneously, as a nurse explained:

“When you have … beginning-of-the-shift huddles … that makes it a little harder … to physically distance yourself when you have now 12 or 13 people … between the day shift and night shift together.”

Similarly, the hospital workflow led to more HCWs present (eg, consulting services, support staff, trainees, etc.) at certain times (eg, weekday mornings or afternoons). Fatigue at the end of a shift may lead HCWs to de-emphasize physical distancing in the interest of expediency, as a nurse explained: “Everyone’s trying to get their last task done and give updates so they can go home, and sometimes the social distancing kind of goes out the window …”

Cultural factors also played a role in physical distancing, as noted in interviews. It was difficult for HCWs to ask those higher in the hierarchy, or in a different hierarchy (eg, resident physicians versus nurses) to physically distance. Hierarchy even determined where HCWs sat; for example, intern and senior resident physicians sat on opposite sides of a workroom. However, leaders promoted physical distancing, as a resident physician explained:

“People who typically have more training or are considered our advisors or mentors or … higher-up physicians, those guys are pretty good at being responsible and … calling out when we need to remain physically distanced.”

At the hospital level, inconsistent messaging was a barrier to physical distancing, as a resident physician said: “I think it definitely bred … a mistrust of the rules because they were changing so quickly.”

In interviews, HCWs suggested organizational strategies to improve physical distancing. HCWs suggested recognizing and rewarding staff and their efforts. HCWs also suggested that a physical distancing champion could remind HCWs to physically distance. They also changed meetings and rounds to allow spacing between HCWs.

External environment characteristics

In interviews, the external environment was described as providing barriers and facilitators to physical distancing. Some HCWs believed that regulatory agencies prevented physical distancing interventions, as a nurse said:

There’s no tape on the ground, which I know [The Joint Commission says], ‘… don’t put tape down or we’re going to burn your building down,’ but … there’s nothing to indicate how far away you should stay.”

Discussion

Physical distancing among HCWs is essential in preventing SARS-CoV-2 transmission among staff. SARS-CoV-2 cases in HCWs and outbreaks frequently originate from contacts with colleagues.2,12,13 We used multiple qualitative methods to characterize physical distancing among HCWs on a non–COVID-19 medical unit. HCWs often spent a significant portion of their day in close proximity. High-risk interactions were particularly common during rounds, reporting, and signing out. Although others have used cellular data to monitor region-wide physical distancing,14 to our knowledge, this is the first report to describe physical distancing among HCWs.

We identified multiple barriers to physical distancing among HCWs from the observations and the interviews. Familiarity and comfort with coworkers, along with the desire to maintain relationships with other HCWs, impacted physical distancing in the study. Multiple reports have described the negative impact of physical distancing on psychological well-being and relationships.15,16 Supporting work relationships while physical distancing is essential, through planned activities such as videoconference-assisted gatherings or physically distanced outdoor activities. As suggested in interviews, hospital leadership should recognize staff for physically distancing. Celebrating staff is a key component of other quality improvement interventions and may be similarly important in physical distancing.17

The physical environment and tools and technologies were also important in physical distancing. We found that computer-generated spacing and room layout were vital. Others have hypothesized that workrooms in many hospitals may detrimentally impact physical distancing,4,18 but none have demonstrated this empirically. Meanwhile, confidential patient information required conversations in close proximity; videoconferencing facilitated these discussions. Based on our findings, we suggest that ways to improve physical distancing include strict occupancy limits, using available space, removing chairs, spacing computers, and using cognitive aids (eg, floor signs, room occupancy limitations, and signage).

The organization impacted physical distancing. Shift times resulted in the presence of many HCWs at once; based on our findings, adjusting shifts and hospital workflow could improve physical distancing. Our findings suggest that having a physical distancing champion19 and developing a culture of physical distancing, where HCWs feel empowered to speak up, could help physical distancing.

Our study had many strengths. Our use of qualitative methods uncovered a depth of information about improving physical distancing. We were able to triangulate our findings by using 2 qualitative methods, better supporting our conclusions. We involved multiple HCW roles to gain a broader understanding.

Our study has several limitations. It was performed on one unit at an academic medical center in an American city during a period when community prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 had temporarily decreased and prior to vaccine availability. These results may be different on different units, hospitals, regions, community prevalence, or vaccination status. We anticipate that findings from this study could be extrapolated to other scenarios. We also focused on times when more HCWs were present to better capture an HCW’s day. This factor may have led to an overestimation of the duration spent in close proximity; however, the observations fit well with interview findings. Future work could quantify the time HCWs spend in close proximity.

We found that HCWs spent much of their work in close proximity. Strategies to improve physical distancing include rewarding positive behavior, modeling or assigning monitors for physical distancing, and encouraging social connections while physically distancing. In addition, computer workstations and work rooms could be restructured to allow physical distancing, with cognitive aids as reminders for appropriate spacing. Rounds and meetings could be conducted with videoconferencing. Signing out of a shift could be reorganized to avoid close contact. Although further research is required to understand the impact of these strategies, our findings offer actionable approaches to improve physical distancing on hospital units and to prevent HCW-to-HCW transmission during the COVID-19 pandemic. We believe that our findings will continue to be relevant as the pandemic evolves.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions of the medicine unit in assisting with this project.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Sara Pau and for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Epicenters Program

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/ice.2021.154.

click here to view supplementary material

Financial support

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Epicenter Program (COVID-19 supplement to grant no. 6 U01CK000554-02-02).

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

References

- 1.Social distancing: keep a safe distance to stop the spread. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/social-distancing.html. Published 2020. Updated November 17, 2020. Accessed March 19, 2021.

- 2. Schneider S, Piening B, Nouri-Pasovsky PA, Kruger AC, Gastmeier P, Aghdassi SJS. SARS-CoV-2 cases in healthcare workers may not regularly originate from patient care: lessons from a university hospital on the underestimated risk of healthcare worker to healthcare worker transmission. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2020;9:192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Knoll RL, Klopp J, Bonewitz G, et al. Containment of a large SARS-CoV-2 outbreak among healthcare workers in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2020;39(11):e336–e339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arora VM, Chivu M, Schram A, Meltzer D. Implementing physical distancing in the hospital: a key strategy to prevent nosocomial transmission of COVID-19. J Hosp Med 2020;15:290–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wilson JR, Haines H, Morris W. Participatory ergonomics. In: Wilson JR, Corlett EN, eds. Evaluation of Human Work, 3rd edition. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor and Francis; 2005:933–962. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carayon P, Hundt AS, Karsh BT, et al. Work system design for patient safety: the SEIPS model. Qual Saf Health Care 2006;15:150–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trends in confirmed cases: Maryland. Johns Hopkins University and Medicine Coronavirus Resource Center website. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/new-cases-50-states/maryland. Published 2021. Accessed January 12, 2021.

- 8. Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing Qualitative Research. Washington, DC: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Method 2006;18:59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kaufmann CP, Stampfli D, Hersberger KE, Lampert ML. Determination of risk factors for drug-related problems: a multidisciplinary triangulation process. BMJ Open 2015;5(3):e006376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res 2007;42:1758–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Statement for media regarding COVID-19 cluster. Brigham and Women’s Hospital website. https://www.brighamandwomens.org/about-bwh/newsroom/press-releases-detail?id=3684. Published 2020. Updated October 16, 2020. Accessed March 23, 2021.

- 13. Oxner R. Costume may have contributed to an outbreak at California hospital, infecting 44. National Public Radio website. https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2021/01/04/953287746/costume-may-have-contributed-to-an-outbreak-at-california-hospital-infecting-44. Published 2021. Updated January 4, 2021. Accessed March 23, 2021.

- 14. Narayanan RP, Nordlund J, Pace RK, Ratnadiwakara D. Demographic, jurisdictional, and spatial effects on social distancing in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One 2020;15(9):e0239572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goodwin R, Hou WK, Sun S, Ben-Ezra M. Psychological and behavioural responses to COVID-19: a China–Britain comparison. J Epidemiol Commun Health 2021;75:189–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goodwin R, Hou WK, Sun S, Ben-Ezra M. Quarantine, distress and interpersonal relationships during COVID-19. Gen Psychiatr 2020;33(6):e100385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pronovost PJ, Berenholtz SM, Goeschel CA, et al. Creating high reliability in healthcare organizations. Health Serv Res 2006;41:1599–1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Parmasad V, Keating JA, Carayon P, Safdar N. Physical distancing for care delivery in healthcare settings: considerations and consequences. Am J Infect Control 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19. Zavalkoff S, Korah N, Quach C. Presence of a physician safety champion is associated with a reduction in urinary catheter utilization in the pediatric intensive care unit. PLoS One 2015;10(12):e0144222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/ice.2021.154.

click here to view supplementary material