Abstract

Measurement of urinary metanephrines in spot samples is used for the diagnosis of canine pheochromocytoma (PC). We describe a simple analytical method based on liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for measuring free metanephrine (MN) and normetanephrine (NMN) in spot urine samples. Using the developed method, we evaluated the stability of urinary free-MN and free-NMN at various storing conditions. In addition, we assessed the feasibility of urinary free-MN and -NMN measurement for diagnosing PC. Urine samples were mixed with stable isotope internal standards and thereafter purified by ultrafiltration. The purified samples were analyzed by LC-MS/MS in the multiple reaction monitoring mode after separation on a multimode octa decyl silyl column. The coefficient of variation of free-MN and -NMN measurement was 7.6% and 5.5%, respectively. The linearity range was 0.5–10 µg/l for both analytes. Degradation was less than 10% for both analytes under any of the storage conditions. The median free-NMN ratio to creatinine of 9 PC dogs (595, range 144–47,961) was significantly higher (P<0.05) than that of 13 dogs with hypercortisolism (125, range 52–224) or 15 healthy dogs (85, range 50–117). The developed method is simple and may not require acidification of spot urine. The results of this preliminary retrospective study suggest that the measurement of urinary free metanephrines is a promising tool for diagnosing canine PC.

Keywords: canine, liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry, normetanephrine, pheochromocytoma, urinary metanephrines

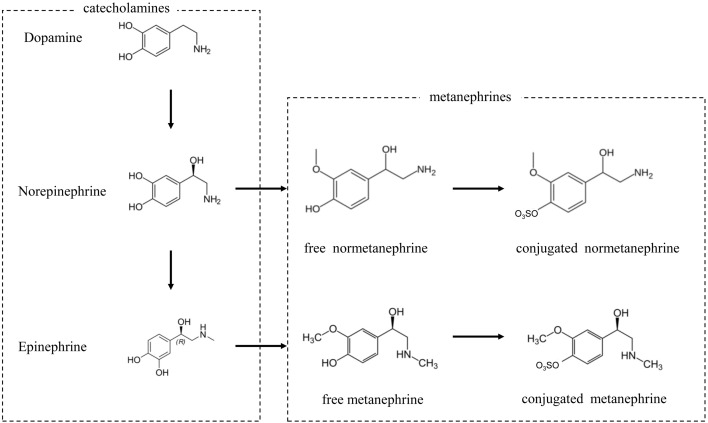

Primary adrenal gland tumor represents 1–2% of all canine tumors [16]. Adenocarcinoma, adenoma, and pheochromocytoma (PC) are the most common primary adrenal gland tumors. Pheochromocytoma originates from adrenal chromaffin cells in adrenal medulla, and accounts for up to one third of primary adrenal gland tumors [1, 4, 8, 13,14,15, 17, 25]. Functioning PCs secrete excessive amount of catecholamines and leads to clinical signs including hypertension, weakness/lethargy, panting/tachypnea, polyuria and polydipsia, and tachycardia. Diagnosis of canine PC remains challenging because reliable diagnostic methods are not wildly available. In human medicine, diagnosis of PC is based on the measurement of catecholamines and their methylated derivatives metanephrines (Fig. 1) in 24 hr urine or in plasma. In dogs, a few studies investigated the clinical feasibility of measuring urine or plasma catecholamines and metanephrines [3, 11, 12, 19, 21]. One comprehensive study showed that urinary normetanephrine: creatinine ratio was superior to other urinary and plasma catecholamines and metanephrines in discriminating canine PC from hypercortisolism and nonadrenal disease [21].

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of catecholamine metabolism.

Measurement of urinary catecholamines and metanephrines in dogs has been established using spot urine samples and their concentration are correlated with urinary creatinine concentration [11]. The reported analytical method of quantifying total (i.e., free and conjugated) catecholamines and metanephrines in dogs requires specific biochemical techniques using high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrochemical detection (HPLC-ECD). Acidification of urine samples in clinics is a critical step for correct analysis of catecholamines because catecholamines are degraded by oxidation in alkaline urine [20]. Metanephrines, meanwhile, are relatively stable even in alkaline urine, and it is suggested that acidification is not mandatory for metanephrines if samples are immediately analyzed or frozen [23]. In addition to urinary acidification, it is needed that analytes are separated and pre-concentrated from urine using solid-phase extraction. The clean-up and extraction steps are relatively laborious and slow. Moreover, it is known that some drugs interfere HPLC-ECD analysis [22]. Liquid chromatography with triple quadrupole mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) has become more popular in biochemical analysis because of its high detection sensitivity and specificity. Furthermore, new column technology developed during the past decades has achieved in the measurement of catecholamines and metanephrines with increased resolving power. Herein we developed a rapid and simple analytical method using ultrafiltration and LC-MS/MS for quantifying free metanephrines in unpreserved urine samples. We investigated the stability of urinary free metanephrines in urine and the feasibility of urinary free metanephrines measurement for diagnosis of canine PC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Spot urine samples were collected by cystocentesis from healthy six adult beagles, owned in the laboratory animal facility of the Graduate School of Veterinary Medicine, Hokkaido University. The animal experiment was approved by the Experimental Animals Committee of Hokkaido University (No. 18-0142). In addition, 9 urine samples derived by cystocentesis during routine medical checkup were kindly provided by the blood donation program, Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, Hokkaido University. Fifteen dogs were defined healthy based on history, physical examination, complete blood count, blood biochemistry, urinary analysis, and abdominal sonography. The median age of healthy dogs was 3 years (range 1–8 years) and body weight ranged between 9.4 and 19.3 kg (median 12.6 kg). Thirteen were intact females and 2 were intact males.

Urine samples obtained from 9 dogs with PC, 13 dogs with hypercortisolism (HC) were retrospectively included. Dogs were represented to Hokkaido University Veterinary Teaching Hospital between June 2017 and July 2019. Written informed consent was signed by all owners before urine collection. Urines samples were collected by cystocentesis in clinics during abdominal ultrasound examination and stored at −20 or −80°C with or without acidification until the measurements.

The criteria of PC were (1) histopathologic examination of the adrenal gland tumor after adrenalectomy (4 dogs); or (2) urinary total normetanephrine: creatinine ratio measured by a commercial laboratory was higher than the established cut-off value of 3 times the upper range of normal (>369, 5 dogs) [19]. The median age of PC dogs was 11 years (range 8–15 years) and body weight ranged between 3.5 and 13.22 kg (median 6.6 kg). Four dogs were neutered females 5 were males (1 intact). At presentation 8 dogs showed at least one of clinical sings; weakness (4 dogs), panting (1 dog), polyuria/polydipsia (2 dogs), abdominal pain (1 dog), and gastrointestinal sing (4 dogs). In the remaining 1 dog, unilateral adrenal mass was incidentally identified by abdominal sonography in a referring hospital.

Thirteen dogs showed clinical sings that were consistent with HC (polyuria/polydipsia, polyphagia, skin problems, panting, and weakness). Abdominal sonography identified unilateral adrenal mass in 7 dogs and bilateral enlargement in 6 dogs. Diagnosis was confirmed by (1) histopathologic examination of the adrenal gland tumor after adrenalectomy (4 dogs); or (2) positive results of ACTH stimulation test or low-dose dexamethasone suppression test (9 dogs). The median age of HC dogs was 10.5 years (range 6–15 years) and body weight ranged between 3.58 and 15.66 kg (median 6.0 kg). Six dogs were neutered females and 7 were males (3 intact). On histopathological examination, 2 of 4 dogs had adrenocortical carcinoma and the others had adrenocortical adenoma. Nine HC dogs without histopathology were treated with trilostane for at least 3 months, and the clinical sings were well-controlled by the treatment.

Chemicals

Metanephrine (MN), normetanephrine (NMN), creatinine (Cr), and three internal standards (MN-d3, NMN-d3 and Cr-d3) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Analytical grade of all reagents and double distilled water (DDW) were obtained from Kanto-Kagaku (Tokyo, Japan).

Sample preparation and LC/MS conditions

For free MN (fMN) and free NMN (fNMN) measurement, 10 µl of urine were added to 450 µl of DDW and 50 µl of mixed internal standard solution. The final concentration of the internal standards was 50 µg/l each. The mixture was then ultrafiltered using Nanostep 3K Omega (Pall Corp., Port Washington, NY, USA) and a centrifuge (Sorvall ST 8FR, Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 10,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature. The filtered samples were injected onto an Agilent 6495B triple quadrupole LC/MS (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Separation was performed on a Scherzo SM-C18 column (3 µm, 4.6 × 50 mm; Imtakt Corp., Kyoto, Japan). The chromatographic gradient program was started at 90% mobile phase A (10 mmol/l ammonium acetate in water) with 10% mobile phase B (100 mmol/l ammonium acetate in water: methanol=3:1) at a flow rate 0.4 ml/min. This was followed by an 8 min gradient to 50% A and 50% B and a 2 min gradient to 90% A and 10% B. The detection was performed with a positive electrospray ionization (ESI) mode. The triple quadrupole was operated in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode by monitoring of a quantifier and qualifier (Table 1).

Table 1. Multiple-reaction monitoring (MRM) conditions for analytes and their internal standards.

| Molecular weight (g/mol) | MRM fragmentation transition (m/z) | Collision energy (eV) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metanephrine | 197 | 180.0>165.4 Quantifier | 16 |

| 180.0>148.0 Qualifier | 16 | ||

| Metanephrines-d3 | 200 | 183.0>168.1 | 16 |

| Normetanephrine | 183 | 166.0>134.0 Quantifier | 16 |

| 166.0>106.1 Qualifier | 16 | ||

| Normetanephrine-d3 | 186 | 169.2>137.1 | 16 |

| Creatinine | 113 | 113.9>43.0 Quantifier | −39 |

| 113.9>86.0 Qualifier | −39 | ||

| Creatinine-d3 | 116 | 116.9>47.1 | −19 |

For Cr measurement, 10 µl of urine were diluted by 990 µl of DDW. Ten microliters of the diluted urine were mixed with 990 µl of the internal standard solution (200 µg/l). The mixed solutions were injected onto an LC/MS-8040 (Shimazu, Kyoto, Japan). Separation was performed on an Asahipak NH2P-40 2D column (4 µm, 2.0 × 150 mm; Showa Denko K. K., Tokyo, Japan). The chromatographic gradient was started at 100% mobile phase A (50 mmol/l formic acetate in water) with 100% mobile phase B acetonitrile at a flow rate 0.04 and 0.36 ml/min, respectively. The detection was performed with a positive ESI mode. The triple quadrupole was operated in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode by monitoring of a quantifier and qualifier (Table 1).

Assay performance was evaluated by a coefficient of variation (CV), lower limit of detection (LOD), lower limit of quantification (LLOQ), and matrix effect. Coefficient of variation was determined with eight different measurements of the same urine sample spiked with 50 µg/l of the internal standard solution.

Peak area ratio=(peak area of MN or NMN) / (peak area of each internal standard)

CV=(the standard deviation of peak area ratio) / (the average of peak area ratio)

Lower limit of detection was established on seven different measurements of 0.5–10 µg/l standard solutions. Lower limit of detection was defined as the lowest concentration with a signal-to-noise ratio greater than ten, and a relative standard deviation of peak area of chromatogram was less than ten. Lower limit of quantification was determined as the three-fold higher concentration of LOD. The matrix effect was evaluated by a matrix factor, which indicates the effects of co-eluting matrix components on the ionization of the target analytes [5].

Matrix factor=(peak area of the internal standard in urine) / (peak area of the internal standard in DDW) × 100

Sample stability

To investigate the stability of fMN and fNMN in urine, a pooled urine sample was divided into 3 aliquots; (i) immediately stored, (ii) immediately acidified to pH 5 with adding 12 mol/l hydrochloric acid solution (Kanto-Kagaku), (iii) immediately alkalized to pH 9 with 20 w/v% sodium hydroxide solution (Kanto-Kagaku). Each aliquot was divided into 4 sets of 20 storing conditions; −80°C, −20°C, 4°C, room temperature, or 30°C for 12 hr, 24 hr, 2 days, or 7 days before LC-MS/MS measurement.

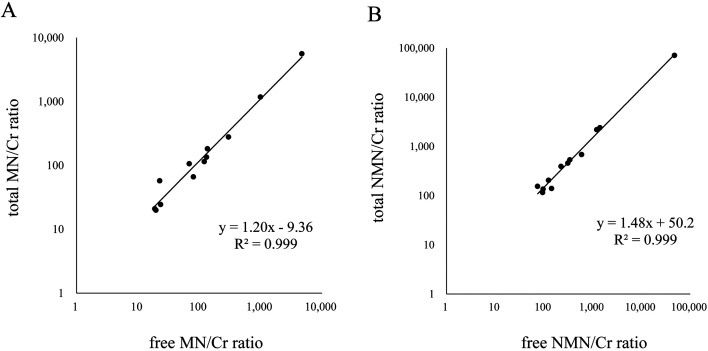

Method comparison

Urinary total (i.e. free + conjugated) MN and NMN ratios to Cr of 12 dogs (7 PC dogs and 5 ACT dogs) were measured by a commercial laboratory (BML, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The ratio of urinary total MN and NMN to Cr were compared with the ratio of urinary free MN and NMN to Cr.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with a commercial software (JMP Pro version 14.0, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Differences in fMN/Cr and fNMN/Cr among healthy, PC, ACT, and PDH dogs was assessed using Steel-Dwass test. A P value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

LC/MS method

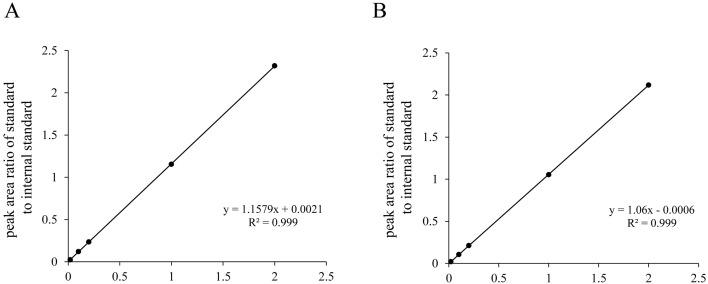

Calibration curves were run with every measurement and were included in analysis. Pearson correlation was used to evaluate the linearity of the calibration curves (Fig. 2). The CV of fMN and fNMN was 7.6% and 5.5%, respectively. For both fMN and fNMN, LOD was 0.5 µg/l and thus LLOQ was 1.5 µg/l. The matrix factor for fMN and fNMN was 34.7% and 25.9%, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Linearly of a calibration curve for (A) free MN and (B) free NMN. MN, metanephrine; NMN, normetanephrine.

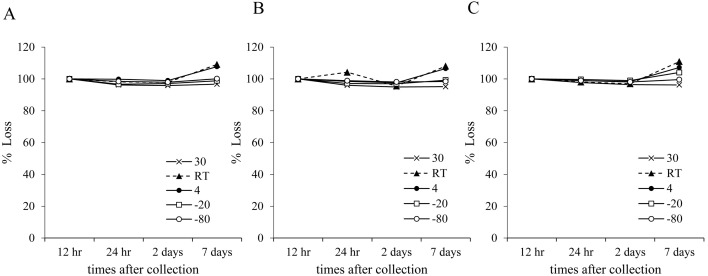

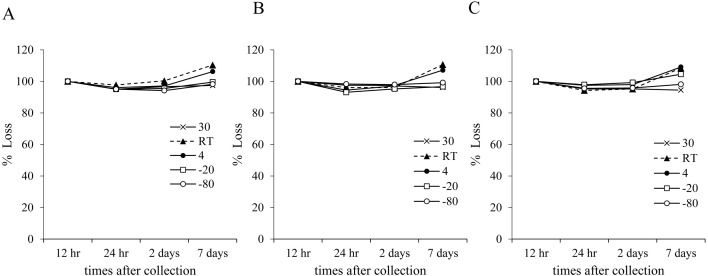

Stability of free metanephrines in urine

Free-MN was stable for 2 days at any pH with less than a 5% decrease in concentration (Fig. 3). However, if stored at 4°C or room temperature for 7 days, urinary fMN concentration increased by less than 7% at any pH. In addition, at pH 9.0, fMN showed a slight increase (4%) in concentration when stored at −20°C. Free-NMN was stable (<5% loss) for 2 days at any temperature, and for 7 days at 30 or −80°C (Fig. 4). When urine was stored for 7 days at either 4°C or room temperature at any pH, fNMN concentration increased by less than 10%. At pH 9.0, a 5% increase in the concentration was observed when stored at −20°C for 7 days.

Fig. 3.

The average of free MN concentration in urine during the storage. One pooled urine sample was divided into three aliquots; (A) preserved at pH 5, (B) unpreserved, and (C) preserved at pH 9. Each aliquot was stored at various temperature for up to 7 days. MN, metanephrine; RT, room temperature.

Fig. 4.

The average of free NMN concentration in urine during the storage. One pooled urine sample was divided into three aliquots; (A) preserved at pH 5, (B) unpreserved, and (C) preserved at pH 9. Each aliquot was stored at various temperature for up to 7 days. NMN, normetanephrine; RT, room temperature.

Method comparison

Using 12 patient samples, urinary free metanephrines ratios to Cr were compared with urinary total metanephrines ratios to Cr. In simple linear regression models, significant relationships were found between total and free metanephrines ratios to Cr (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

The relationship between the free-metanephrines to creatinine ratio and the total-metanephrines to creatinine ratio; (A) MN and (B) NMN. MN, metanephrine; NMN, normetanephrine; Cr, creatinine.

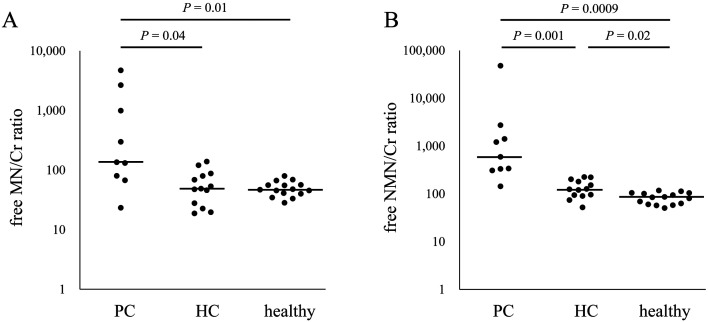

Application the method to clinical samples

(Fig. 6)

Fig. 6.

Urinary free metanephrines to creatinine ratio in clinical samples. (A) Free MN/Cr of PC dogs (n=9) was higher than that of HC (n=13) and healthy dogs (n=15). (B) Free-NMN/Cr of PC dogs was significantly higher than that of HC and healthy dogs. Bars, the median ratio of each group. MN, metanephrine; NMN, normetanephrine; Cr, creatinine; PC, pheochromocytoma; HC, hypercortisolism.

Median fMN/Cr in dogs with PC (136, range 23–4,703) was higher in HC dogs (49, range 19–139, P=0.04) and healthy dogs (47, range 28–80, P=0.01). Median fNMN/Cr of PC dogs (595, range 144–47,961) was significantly higher than that of HC dogs (125, range 52–224, P=0.001) and that of healthy dogs (85, range 50–117, P=0.0009). However, fNMN/Cr in one dog with PC (144) overlapped with that of 5 HC dogs. The particular PC dog and 2 of the 5 HC dogs were diagnosed based on histopathological examination of the adrenal gland tumor.

The ROC analysis indicated the cutoff values were 131 for fMN/Cr and 309 for fNMN/Cr. When the cutoff values >131 for fMN/Cr was used, the sensitivity for detection of PC was 67%, with a specificity of 96% and an accuracy of 89%. If the cutoff value of >309 was used, fNMN/Cr in this study indicated PC with the sensitivity of 89%, the specificity of 100%, and the accuracy of 97%. The previous study recommended the cutoff values for total-NMN/Cr of 4 times the upper limit of normal [21], which corresponded 468 of free-NMN/Cr in this study. With the cutoff value for free-NMN/Cr >468 was used, the sensitivity was reduced (56%) while the specificity and accuracy were comparable (100% and 89%, respectively).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we developed a simple analytical method for the measurement of urinary fMN and fNMN in spot urine samples. Ion suppression phenomena, decease in the production of analyte ions, is the major cause of imprecision for LC-MS/MS analysis [5, 10, 16]. Sample clean-up and extraction methods, such as solid phase extraction, are required to reduce ion suppression by endogenous materials from biological samples. Furthermore, MN and NMN are hardly retained on conventional reverse phase columns because of their polar properties (i.e., hydrophilic) [9, 18]. The developed method was equipped with the ultrafiltration and the multimode octa decyl column (Scherzo SM-C18). Ultrafiltration in this study removed interferences with their molecular size more than 3,000. It is well known that endogenous macromolecules, such as proteins and lipids, in biological samples can cause ion suppression [10]. In addition to macromolecules, hydrophilic inorganic salts are possible interferences in urine [5]. The ultrafiltration method may mainly remove macromolecules and reduce ion suppression caused by matrix effect. Although the matrix factor suggests relative ion suppression possibly caused by hydrophilic inorganic salts, stable isotope labeled internal standards might help in quantifying urinary free metanephrines in filtrated urine. The previous study showed that the combination of dilution and centrifugation was enough for the clean-up step of urinary analysis using LC-ESI-MS/MS [5]. The ultrafiltration method may be feasible for a rapid clean-up step in urinary metanephrines quantification. The multimode octa decyl silyl column consists of conventional octa decyl silica for reversed phase chromatography, and weak anion and cation resins for ion exchanges modes. This particular column is superior to the conventional octa decyl silyl column in separating polar compounds at neutral pH condition [8, 24]. Metanephrines are positively charged in urine, and thus analytes might be adequately retained in the column and separated form interferences in urine. The results of this study suggest that the combination of ultrafiltration and the multimode column contributes to develop a rapid and simple quantification method of urinary fMN and fNMN.

This study demonstrated fMN and fNMN in spot urine were relatively stable over several days. The previous study with human control urine showed that urinary free metanephrines were stable for one week at any temperature at any pH, and for several weeks when stored at −18°C at any pH [23]. Slight increases in fMN and fNMN concentration were observed in this study, suggesting the possible deconjugation of conjugated compounds to free compounds in urine during the storage. However, the less than 10% increases in concentration may not be significant changes because the CV of fMN and fNMN in this study was 7.6% and 5.5%, respectively. Change in concentration was regarded as significant if the measured change was more than 10% or exceeded two-times of CV in previous studies [20, 23]. Our results suggest that acidification of urine is not necessary for measurement of fMN and fNMN in spot urine samples as long as samples are delivered to a laboratory and analyzed within a few days after the collection.

The results of this preliminary study suggest that free metanephrines in unpreserved spot urine samples, especially fNMN/Cr, is feasible for discriminating PC from other adrenal diseases. Previous studies reported that urinary total-NMN/Cr was the best parameter to differentiate canine PC from other diseases [19, 21]. In addition to total-NMN/Cr ratio, urinary free-NMN/Cr may be a potential diagnostic tool for canine PC. However, the precise diagnostic value of urinary free metanephrines has not been confirmed in this study. It is likely that urinary free-NMN/Cr of dogs with PC in the present study was high because PC was diagnosed based on urinary total-NMN/Cr. The concentrations of urinary free metanephrines significantly correlated with those of urinary total metanephrines (Fig. 5). Unfortunately, the sample size of this preliminary study was not enough to provide a validation cohort for assessing the cutoff value for fNMN/Cr. Future studies may validate an appropriate cut off value for fNMN/Cr for diagnosing canine PC. In one dog with PC, urinary fNMN/Cr showed the low value despite histopathological diagnosis of PC. It may be possible that the particular PC was nonfunctioning tumor [2, 7]. In addition, rarer PCs in human purely secrete dopamine instead of either epinephrine or norepinephrine [6]. To the authors’ knowledge, there has not been established histopathological makers of the secreting function of PCs.

In conclusion, the developed method using LC-MS/MS would be simple and may not require an additive in clinics. Quantification of free metanephrines in spot urine has a potential for discriminating PCs form other adrenal diseases.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

This work was the result of using research equipment shared in MEXT Project for promoting public utilization of advanced research infrastructure (Program for supporting introduction of the new sharing system, Grant Number JPMXS0420100619). This study was partly supported by Grants in Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (YI, 18H0413208; MT, 20H03139).

REFERENCES

- 1.Barrera J. S., Bernard F., Ehrhart E. J., Withrow S. J., Monnet E.2013. Evaluation of risk factors for outcome associated with adrenal gland tumors with or without invasion of the caudal vena cava and treated via adrenalectomy in dogs: 86 cases (1993–2009). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 242: 1715–1721. doi: 10.2460/javma.242.12.1715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barthez P. Y., Marks S. L., Woo J., Feldman E. C., Matteucci M.1997. Pheochromocytoma in dogs: 61 cases (1984–1995). J. Vet. Intern. Med. 11: 272–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.1997.tb00464.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cameron K. N., Monroe W. E., Panciera D. L., Magnin-Bissel G. C.2010. The effects of illness on urinary catecholamines and their metabolites in dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 24: 1329–1336. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2010.0595.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavalcanti J. V. J., Skinner O. T., Mayhew P. D., Colee J. C., Boston S. E.2020. Outcome in dogs undergoing adrenalectomy for small adrenal gland tumours without vascular invasion. Vet. Comp. Oncol. 18: 599–606. doi: 10.1111/vco.12587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dams R., Huestis M. A., Lambert W. E., Murphy C. M.2003. Matrix effect in bio-analysis of illicit drugs with LC-MS/MS: influence of ionization type, sample preparation, and biofluid. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 14: 1290–1294. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(03)00574-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubois L. A., Gray D. K.2005. Dopamine-secreting pheochromocytomas: in search of a syndrome. World J. Surg. 29: 909–913. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7860-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilson S. D., Withrow S. J., Wheeler S. L., Twedt D. C.1994. Pheochromocytoma in 50 dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 8: 228–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.1994.tb03222.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guak H., Al Habyan S., Ma E. H., Aldossary H., Al-Masri M., Won S. Y., Ying T., Fixman E. D., Jones R. G., McCaffrey L. M., Krawczyk C. M.2018. Glycolytic metabolism is essential for CCR7 oligomerization and dendritic cell migration. Nat. Commun. 9: 2463. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04804-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He H., Carballo-Jane E., Tong X., Cohen L. H.2015. Measurement of catecholamines in rat and mini-pig plasma and urine by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry coupled with solid phase extraction. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 997: 154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2015.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Issaq H. J., Fox S. D., Chan K. C., Veenstra T. D.2011. Global proteomics and metabolomics in cancer biomarker discovery. J. Sep. Sci. 34: 3484–3492. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201100528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kook P. H., Boretti F. S., Hersberger M., Glaus T. M., Reusch C. E.2007. Urinary catecholamine and metanephrine to creatinine ratios in healthy dogs at home and in a hospital environment and in 2 dogs with pheochromocytoma. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 21: 388–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2007.tb02980.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kook P. H., Grest P., Quante S., Boretti F. S., Reusch C. E.2010. Urinary catecholamine and metadrenaline to creatinine ratios in dogs with a phaeochromocytoma. Vet. Rec. 166: 169–174. doi: 10.1136/vr.b4760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kyles A. E., Feldman E. C., De Cock H. E. V., Kass P. H., Mathews K. G., Hardie E. M., Nelson R. W., Ilkiw J. E., Gregory C. R.2003. Surgical management of adrenal gland tumors with and without associated tumor thrombi in dogs: 40 cases (1994–2001). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 223: 654–662. doi: 10.2460/javma.2003.223.654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang J. M., Schertel E., Kennedy S., Wilson D., Barnhart M., Danielson B.2011. Elective and emergency surgical management of adrenal gland tumors: 60 cases (1999–2006). J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 47: 428–435. doi: 10.5326/JAAHA-MS-5669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lunn K. F., Page R. L.2013. Tumors of the endocrine system. pp. 504–531. In: Withrow and MacEwen’s Small Animal Clinical Oncology, 5th ed. (Withrow, S. J., Vail, D. M. and Page, R. L. eds.), Elsevier, St. Louis. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mallet C. R., Lu Z., Mazzeo J. R.2004. A study of ion suppression effects in electrospray ionization from mobile phase additives and solid-phase extracts. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 18: 49–58. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massari F., Nicoli S., Romanelli G., Buracco P., Zini E.2011. Adrenalectomy in dogs with adrenal gland tumors: 52 cases (2002–2008). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 239: 216–221. doi: 10.2460/javma.239.2.216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nema T., Chan E. C. Y., Ho P. C.2010. Application of silica-based monolith as solid phase extraction cartridge for extracting polar compounds from urine. Talanta 82: 488–494. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2010.04.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quante S., Boretti F. S., Kook P. H., Mueller C., Schellenberg S., Zini E., Sieber-Ruckstuhl N., Reusch C. E.2010. Urinary catecholamine and metanephrine to creatinine ratios in dogs with hyperadrenocorticism or pheochromocytoma, and in healthy dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 24: 1093–1097. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2010.0578.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts N. B., Higgins G., Sargazi M.2010. A study on the stability of urinary free catecholamines and free methyl-derivatives at different pH, temperature and time of storage. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 48: 81–87. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2010.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salesov E., Boretti F. S., Sieber-Ruckstuhl N. S., Rentsch K. M., Riond B., Hofmann-Lehmann R., Kircher P. R., Grouzmann E., Reusch C. E.2015. Urinary and plasma catecholamines and metanephrines in dogs with pheochromocytoma, hypercortisolism, nonadrenal disease and in healthy dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 29: 597–602. doi: 10.1111/jvim.12569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor R. L., Singh R. J.2002. Validation of liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method for analysis of urinary conjugated metanephrine and normetanephrine for screening of pheochromocytoma. Clin. Chem. 48: 533–539. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/48.3.533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willemsen J. J., Ross H. A., Lenders J. W., Sweep F. C.2007. Stability of urinary fractionated metanephrines and catecholamines during collection, shipment, and storage of samples. Clin. Chem. 53: 268–272. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.075218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yanes O., Tautenhahn R., Patti G. J., Siuzdak G.2011. Expanding coverage of the metabolome for global metabolite profiling. Anal. Chem. 83: 2152–2161. doi: 10.1021/ac102981k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshida O., Kutara K., Seki M., Ishigaki K., Teshima K., Ishikawa C., Iida G., Edamura K., Kagawa Y., Asano K.2016. Preoperative differential diagnosis of canine adrenal tumors using tiple-phase helical computed tomography. Vet. Surg. 45: 427–435. doi: 10.1111/vsu.12462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]