Abstract

Objectives

Resident macrophages are well known to be present in the cochlea, but the exact patterns thereof in spiral ligaments have not been discussed in previous studies. We sought to document the distribution of macrophages in intact cochleae using three-dimensional imaging.

Methods

Cochleae were obtained from C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor 1+/GFP mice, and organ clearing was performed. Three-dimensional images of cleared intact cochleae were reconstructed using two-photon microscopy. The locations of individual macrophages were investigated using 100-μm stacked images to reduce bias. Cochlear inflammation was then induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) inoculation into the middle ear through the tympanic membrane. Four days after inoculation, three-dimensional images were obtained.

Results

Macrophages were scarce in areas adjacent to the stria vascularis, particularly the area just beneath it even though many have suspected macrophages to be abundant in this area. This finding remained consistent upon LPS-induced cochlear inflammation, despite a significant increase in the number of macrophages, compared to non-treated cochlea.

Conclusion

Resident macrophages in spiral ligaments are scarce in areas adjacent to the stria vascularis.

Keywords: Macrophages, Cochlea, Spiral Ligament of Cochlea, Stria Vascularis

INTRODUCTION

Resident macrophages in the cochlea have been intensively investigated using advanced immunohistochemistry and laser scanning microscopy techniques. Many studies have reported that cochleae harbor resident macrophages expressing CD45, F4/80, ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1, CD11b, and C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1) [1-4]. These macrophages play important functions in inflammation in response to various insults, including noise exposure, ototoxicity, and infection. Interestingly, some studies have shown that increased numbers of macrophages in response to these insults stem from migrating monocytes, not from pre-existing macrophages [2,5].

According to previous studies, recruited macrophages are distributed widely throughout the cochlea, and resident macrophages are thought to be mainly located in the spiral ligament and stria vascularis [2,3,6]. A few macrophages have been found in Reissner’s membrane and in the basement membrane. Importantly, recruited macrophages can increase significantly in number in the spiral ligament, Reissner’s membrane, and basement membrane and spread to the wall of the scala tympani, scala vestibuli, and spiral limbus. The inferior part of the spiral ligament is believed to be the extracellular migration site of immune cells, as immunohistochemical findings have highlighted a high concentration of macrophages in this area pre- and post-inflammation [2,5].

The spiral ligament is divided into five areas according to the type of fibrocyte that it is composed of. Each type of fibrocyte expresses different cell markers suggestive of different roles. For example, the NKCC1 channel is expressed in type II, IV, and V fibrocytes, and the aquaporin 1 channel is expressed in type III fibrocytes. Na/K-ATPase, which is also an important ion channel for generating the potassium gradient, is highly expressed in type II and V fibrocytes [7,8].

In this study, we sought to document macrophage distribution patterns in the spiral ligament in CX3CR1+/GFP mice, in which monocytes and macrophages in the cochlea can be visualized without immunostaining according to previous studies [9,10]. As conventional cochlear sectioning methods have limitations in terms of generalizing the location of cochlear macrophages due to the thin depth of the section, we applied a novel three-dimensional imaging technique without the need for any tissue preparation. Three-dimensional cochlear imaging was conducted using two-photon microscopy, which has a higher penetration depth and poses less damage to the tissue than confocal microscopy [11,12].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

CX3CR1GFP/GFP C57/BL6 mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) via Orient Bio (Seongnam, Korea). All mice were maintained in a specific pathogen free environment in the animal facility at Avison Biomedical Research Center at Yonsei University College of Medicine (Seoul, Korea). Temperature, humidity, and light/dark cycle were properly controlled, and food and water were accessible ad libitum. Less than five animals were maintained in a single cage. CX3CR1+/GFP mice were produced by crossing wild-type C57/BL6 mice (Orient Bio) with CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice. Randomly selected male and female mice (aged 4-8 weeks and weight 15–25 g) were used in the experiments, and all animals were carefully maintained in cages and were not exposed to noise. After general anesthesia, 5 µL of lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 5 mg/mL) was inoculated in the mouse middle ear through the tympanic membrane in the experimental group. The concentration and amount of injected LPS were based on previous studies [13,14]. The experimental group mice were sacrificed at 1, 4, 7, and 10 days after LPS inoculation. Control group mice were sacrificed without any injection or sacrificed 4 days after 5 µl of PBS inoculation in the middle ear. The right side ear was used in all experimental animals. All experiments were performed during the daytime in the animal laboratory. A heating pad (37°C) was used to maintain the body temperature of the animal during general anesthesia. The animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the Yonsei University College of Medicine (Project No. 2019-0182).

Cochlear preparation

After sacrificing the mice in a CO2 chamber, the bilateral temporal bones of the mice were obtained. The mouse temporal bones were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours in a 4°C room. After fixation, samples were incubated in 1 mL of 0.25 M ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) solution for 24 hours at 4°C for decalcification. Decalcified cochlea were cleared using Binaree Clearing Kits (Binaree, Daegu, Korea). Cleared cochlea were mounted on a silicone bond in the petri dish, with spiral ligaments were positioned at the top. Eighty percent of glycerol was then dropped on the sample, and a cover slide was positioned on it. Distilled water was filled between cover slide and water-immerse lens of the two-photon microcopy.

Imaging

Two-photon microscopy (LSM7MP; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) was used for imaging data generation. Zen software (Carl Zeiss) was used for image acquisition and basic image analysis. To create three-dimensional images and videos, we used IMARIS software (Bitplane, Zurich, Switzerland). The Mai-Tai HP Ti:Sa Deep See laser system (Spectra-Physics, Mountain View, CA, USA) was used to generate excitation lasers with a wavelength of 810 nm. Images were acquired at a resolution of 512× 512 pixels using band-pass filters with 420–480 nm (blue), 500– 550 nm (green), and 575–610 nm (red). A 20× object lens was used in all experiments.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Quantification was performed using Zen software (Carl Zeiss), and the type III fibrocyte area, which is parallel to X-Y plane, was investigated. Regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn as a circle with area of 25,000 µm2 lateral to the stria vascularis. The number of green cells were counted manually between cortical bone and the stria vascularis in each ROI. Kruskal-Wallis test with post-hoc was used to evaluate the significance (P<0.05) of differences between groups. Statistical analysis was performed by IBM SPSS ver. 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

Three-dimensional imaging of intact cochlea

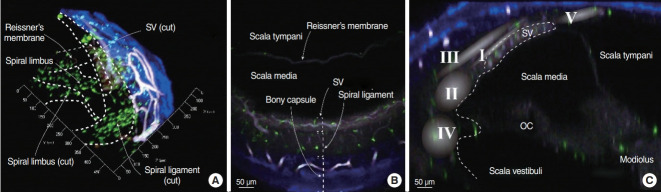

We obtained three-dimensional images of intact cochleae from CX3CR1+/GFP mice using two-photon microscopy (Fig. 1, Supplementary Video 1). The cochlear bony capsule was colored blue, and capillaries were colored white because of endogenous fluorescence. Spiral ligaments appeared as dim endogenous fluorescence, whereas the stria vascularis showed brighter fluorescence. Capillaries in the spiral ligament, including the stria vascularis vessels, were clearly seen with their characteristic branching pattern. Resident macrophages appeared in bright green color. Even though the intensity of fluorescence grew dimmer as the depth increased, macrophages in the spiral ligament were clearly distinguishable.

Fig. 1.

Image of a cleared intact cochlea from a CX3CR1+/GFP mouse using two-photon microscopy. Green cells denote macrophages, blue areas denote the bony capsule of the cochlea, and white colored structures denote vessels. The internal structures of the cochlea are clearly distinguishable without any staining due to the endogenous fluorescence induced by the two-photon laser excitation. (A) Three-dimensional (3D) image of part of the cochlear middle turn. The dotted line marks the microstructures of the cochlea. The X-axis is parallel to the cochlear turn, the Y-axis is parallel to the spiral limbus, and the Z-axis is parallel to the modiolus. (B) XY-plane image obtained from the 3D image. Three layers marked by dotted square brackets. The stria vascularis (SV) shows brighter endogenous fluorescence than that of the spiral ligament. (C) YZ-plane image obtained from the 3D image. Roman numerals in the gradated area denote the area of each fibrocyte type [8]. OC, organ of corti.

Macrophage distribution in untreated cochlea

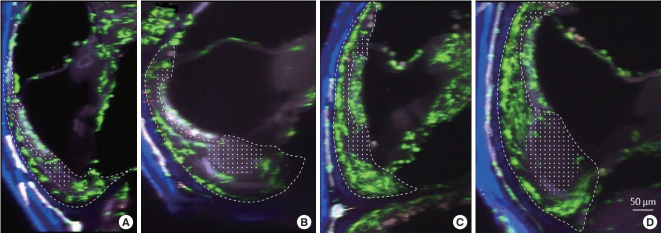

To reduce selection bias, we captured extended images of 100 µm in length along the cochlear turn (images were projected to the sagittal plane). The apical and basal turns showed similar patterns of macrophage distribution (Fig. 2A and B). Notably, the spiral ligament macrophages were not evenly distributed in the sagittal plane. The lateral edge of the spiral ligaments showed dense distributions of macrophages. Perivascular macrophages contacting stria vascularis vessels were also found, and several macrophages were seen at Reissner’s membrane. However, resident macrophages were scarce in the area adjacent to the stria vascularis. In particular, the wide area from the crista basilaris to beneath the stria vascularis showed a lack of macrophages, even though this area was thought to be the primary site where macrophages reside [2].

Fig. 2.

Image along the YZ-plane (100 µm extended) of the spiral ligament of the cochlea from a CX3CR1+/GFP mouse. Green cells denote resident macrophages. The dotted line represents the spiral ligament, and the dotted area marks the area with a lack of macrophages. (A) Middle turn of an untreated cochlea. (B) Basal turn of an untreated cochlea. (C) Middle turn of an inflamed cochlea. (D) Basal turn of an inflamed cochlea. Compared to the untreated cochlea, the inflamed cochlea shows a higher density of green cells. Newly localized macrophage/monocytes are seen in the basilar membrane and in the spiral limbus of the inflamed cochlea. Notably, the areas adjacent to the stria vascularis and beneath it show very few macrophages.

Macrophage distribution in inflamed cochleae

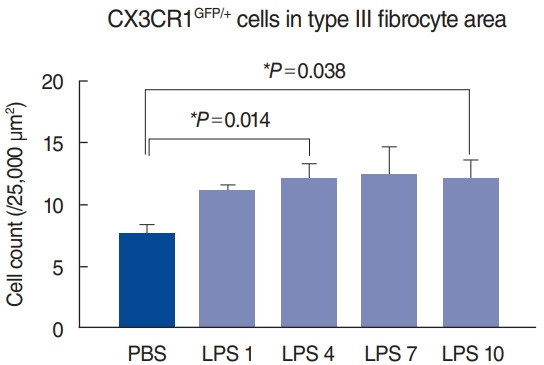

Upon inflammation, macrophages and monocytes are known to migrate robustly into the cochlea. We induced cochlear inflammation using LPS, which was inoculated in the middle ear through the tympanic membrane. At 1, 4, 7, and 10 days after LPS injection, GFP-positive cells (macrophage and monocytes) were present in higher numbers in the cochlea than in the PBS injection group (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the distribution patterns in the spiral ligament were similar to those in the untreated cochlea, even though macrophage density had significantly increased (Fig. 2). In addition, migration of green cells was identified in the basilar membrane and spiral limbus, a finding which is consistent with previous studies [2,5].

Fig. 3.

Statistical analysis of macrophage counts in each sample revealed a significant increase in the number of macrophages after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) injection. At 4 and 10 days after LPS injection, significant increases in macrophages were noted in the type III fibrocyte area, compared to phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-injected cochlea. PBS, sacrificed at 4 days after PBS injection (n=8); LPS 1, sacrificed at 1 day after LPS injection (n=4); LPS 4, sacrificed at 4 days after LPS injection (n=8); LPS 7, sacrificed at 7 days after LPS injection (n=4); LPS 10, sacrificed at 10 days after LPS injection (n=4). *Statistical significance, P<0.05.

DISCUSSION

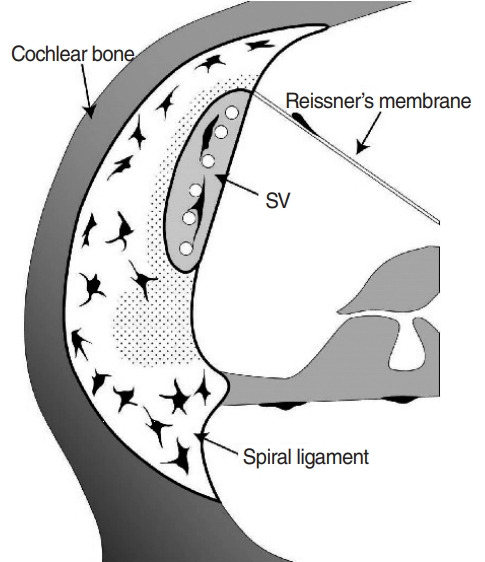

It is generally thought that macrophages are distributed in all areas of the spiral ligament and are more abundant in inferior regions represented by type II and IV fibrocyte zones [2,5,15,16], whereas the organ of Corti lacks macrophages even in inflamed conditions, which seems to be a defense mechanism against collateral damage caused by inflammatory cells [3,17]. In this study, interestingly, we noted consistently low populations of macrophages near the stria vascularis including type II fibrocyte zones (Figs. 2 and 4) in both the untreated and inflamed conditions (Fig. 2).

Fig. 4.

Schematic image of the macrophage distribution pattern in untreated spiral ligaments. Macrophages are colored black, and the dotted area indicates areas lacking macrophages.

Even though we meticulously reviewed previously published studies, we were unable to uncover any images that showed macrophages in the areas that lacked macrophages in this study [2,3,5,16,17]. These areas seem to be protected from the intrusion of macrophages, given the importance of the stria vascularis and its adjacent area in electro-homeostasis of the cochlea, especially potassium recycling. Furthermore, these areas are associated with type I, II, and V fibrocyte zones, and Na/K-ATPase (a critical ion channel for maintaining endocochlear potential) is highly expressed in type II and V fibrocyte zones [8,18,19].

The mechanism protecting these areas from macrophage intrusion is not clear. However, it seems to be associated with intercellular junctions, which are known to form a blood-labyrinth barrier. It does not seem that fibrocytes themselves play a key role in this protection because the areas lacking macrophages did not precisely match with the known zones of each type of fibrocyte. For instance, only the narrow medial area of the type I fibrocyte zone was lacking in macrophages. In 2017, Liu et al. [7] reported that claudin-11, which is a tight junction protein, acts as an ion barrier in the spiral ligament. They showed that claudin-11 was expressed in areas adjacent to the stria vascularis, with a similar pattern to the areas lacking macrophages in our study. However, the wide area beneath the stria vascularis did not match with this protein marker, and no protein marker corresponding to the areas lacking macrophages in this study is yet known to the best of our knowledge.

Three-dimensional images of intact cochleae were used in this study to investigate the exact locations of macrophages, as conventional methods have limitations to generalizing macrophage distribution patterns. For instance, a whole-mount preparation of the spiral ligament inevitably presses the ligament down while it is being mounted on the slide glass, resulting in deformation. Moreover, paraffin sections or cryosections are not free from selection bias due to their thinness. Furthermore, it is hard to obtain consecutively stacked sections of about 100 µm in length. Nevertheless, a major limitation of this study is that we could not find a protein marker that was exclusively expressed in the areas lacking resident macrophages. Consequently, future studies would benefit from focusing on establishing an effective immunostaining protocol for cleared intact cochlea samples and from investigating the key proteins and/or structures that play a role in the protective mechanisms against macrophage intrusion.

In this study, macrophages in the spiral ligament showed consistent patterns of distribution in both untreated and inflamed states. Although the inferior half of the spiral ligament is known to have an abundance of resident macrophages, the area adjacent to the stria vascularis and a large area underneath the stria vascularis showed a lack of macrophages in this study.

HIGHLIGHTS

▪ Resident macrophages in cochlear are not evenly distributed in the spiral ligament.

▪ The region below and adjacent to stria vascularis is a lack of macrophage.

▪ The cochlear macrophages were increased in the inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide inoculation.

▪ The lack-of-macrophage area in spiral ligament is similar even in inflammation status.

Acknowledgments

his research was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2019R1A2C1084033 to Jinsei Jung) and a faculty research grant of Yonsei University College of Medicine (6-2020-0153 to Seong Hoon Bae).

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: SHB. Data curation: SHB, SHK, KMK, JEY. Formal analysis: SHB. Resources: YMH, JYC. Funding acquisition: JJ, SHB. Methodology: SHK, KMK. Supervision: YMH, JYC, JJS. Writing–original draft: SHB. Writing–review & editing: JJ.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary materials can be found via https://doi.org/10.21053/ceo.2020.00395.

Cleared intact cochlea from a CX3CR1+/GFP mouse using two-photon microscopy. Green cells denote macrophages, blue area denotes the bony capsule of the cochlea, and white colored structures denote vessels. The larger grid represents 50 μm, and the smaller grid indicates 10 μm.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wood MB, Zuo J. The contribution of immune infiltrates to ototoxicity and cochlear hair cell loss. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017 Apr;11:106. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirose K, Discolo CM, Keasler JR, Ransohoff R. Mononuclear phagocytes migrate into the murine cochlea after acoustic trauma. J Comp Neurol. 2005 Aug;489(2):180–94. doi: 10.1002/cne.20619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okano T, Nakagawa T, Kita T, Kada S, Yoshimoto M, Nakahata T, et al. Bone marrow-derived cells expressing Iba1 are constitutively present as resident tissue macrophages in the mouse cochlea. J Neurosci Res. 2008 Jun;86(8):1758–67. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang W, Vethanayagam RR, Dong Y, Cai Q, Hu BH. Activation of the antigen presentation function of mononuclear phagocyte populations associated with the basilar membrane of the cochlea after acoustic overstimulation. Neuroscience. 2015 Sep;303:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.05.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tornabene SV, Sato K, Pham L, Billings P, Keithley EM. Immune cell recruitment following acoustic trauma. Hear Res. 2006 Dec;222(1-2):115–24. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kishimoto I, Okano T, Nishimura K, Motohashi T, Omori K. Early development of resident macrophages in the mouse cochlea depends on yolk sac hematopoiesis. Front Neurol. 2019 Oct;10:1115. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.01115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu W, Schrott-Fischer A, Glueckert R, Benav H, Rask-Andersen H. The human “cochlear battery”: claudin-11 barrier and ion transport proteins in the lateral wall of the cochlea. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017 Aug;10:239. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun GW, Fujii M, Matsunaga T. Functional interaction between mesenchymal stem cells and spiral ligament fibrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 2012 Sep;90(9):1713–22. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He W, Yu J, Sun Y, Kong W. Macrophages in noise-exposed cochlea: changes, regulation and the potential role. Aging Dis. 2020 Feb;11(1):191–9. doi: 10.14336/AD.2019.0723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakanishi H, Kawashima Y, Kurima K, Chae JJ, Ross AM, Pinto-Patarroyo G, et al. NLRP3 mutation and cochlear autoinflammation cause syndromic and nonsyndromic hearing loss DFNA34 responsive to anakinra therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Sep;114(37):E7766–75. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1702946114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helmchen F, Denk W. Deep tissue two-photon microscopy. Nat Methods. 2005 Dec;2(12):932–40. doi: 10.1038/nmeth818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Svoboda K, Yasuda R. Principles of two-photon excitation microscopy and its applications to neuroscience. Neuron. 2006 Jun;50(6):823–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J, Chen S, Hou Z, Cai J, Dong M, Shi X. Lipopolysaccharideinduced middle ear inflammation disrupts the cochlear intra-strial fluid-blood barrier through down-regulation of tight junction proteins. PLoS One. 2015 Mar;10(3):e0122572. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richter CA, Amin S, Linden J, Dixon J, Dixon MJ, Tucker AS. Defects in middle ear cavitation cause conductive hearing loss in the Tcof1 mutant mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2010 Apr;19(8):1551–60. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu BH, Zhang C, Frye MD. Immune cells and non-immune cells with immune function in mammalian cochleae. Hear Res. 2018 May;362:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyao M, Firestein GS, Keithley EM. Acoustic trauma augments the cochlear immune response to antigen. Laryngoscope. 2008 Oct;118(10):1801–8. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31817e2c27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du X, Choi CH, Chen K, Cheng W, Floyd RA, Kopke RD. Reduced formation of oxidative stress biomarkers and migration of mononuclear phagocytes in the cochleae of chinchilla after antioxidant treatment in acute acoustic trauma. Int J Otolaryngol. 2011;2011:612690. doi: 10.1155/2011/612690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spicer SS, Schulte BA. The fine structure of spiral ligament cells relates to ion return to the stria and varies with place-frequency. Hear Res. 1996 Oct;100(1-2):80–100. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(96)00106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spicer SS, Schulte BA. Differentiation of inner ear fibrocytes according to their ion transport related activity. Hear Res. 1991 Nov;56(1-2):53–64. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(91)90153-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cleared intact cochlea from a CX3CR1+/GFP mouse using two-photon microscopy. Green cells denote macrophages, blue area denotes the bony capsule of the cochlea, and white colored structures denote vessels. The larger grid represents 50 μm, and the smaller grid indicates 10 μm.