Abstract

Depressive disorder is one of the most widespread forms of psychiatric pathology, worldwide. According to a report by the World Health Organization, the number of people with depression, globally, is increasing dramatically with each year. Previous studies have demonstrated that various factors, including genetics and environmental stress, contribute to the risk of depression. As such, it is crucial to develop a detailed understanding of the pathogenesis of depressive disorder and animal studies are essential for identifying the mechanisms and genetic disorders underlying depression. Recently, many researchers have reported on the pathology of depression via various models of depressive disorder. Given that different animal models of depression show differences in terms of patterns of depressive behavior and pathology, the comparison between depressive animal models is necessary for progress in the field of the depression study. However, the various animal models of depression have not been fully compared or evaluated until now. In this paper, we reviewed the pathophysiology of the depressive disorder and its current animal models with the analysis of their transcriptomic profiles. We provide insights for selecting different animal models for the study of depression.

Keywords: depression, depression animal model, depressive behavior, functional analysis, transcriptomic analysis

Experimental models for the study of depression.

1. OVERVIEW OF DEPRESSIVE DISORDER

Depressive disorder is one of the major emerging psychiatric mood disorders, worldwide. It was reported that around 17% of people experience depression at least once in their lifetime. 1 The symptoms and comorbidity of depression include social withdrawal, disturbed sleep, depressed mood (sadness), apathy, anxiety, changes in food consumption, psychomotor retardation, and memory deficits. 2 Major depressive disorder is mainly characterized by consistently depressive mood, loss of pleasure, appetite pattern change, insomnia, behavior motor retardation, fatigue, and feelings of worthlessness for a minimum of 2‐week period. 3

Depression is considered to be caused by the mutual influence of multiple psychological and social factors as well as epigenetic factors. 4 Physical pain and chronic stress can induce depression and influence its progression and severity. 5 , 6 Cases of depression are heterogeneous in terms of genetic influences, clinical progression, neurobiological changes, and treatment responses to antidepressants. 7 , 8 In recent decades, studies of the progression of depression have reported on abnormalities in brain circuitry and on cellular and molecular alterations in the depressive brain. 9 , 10

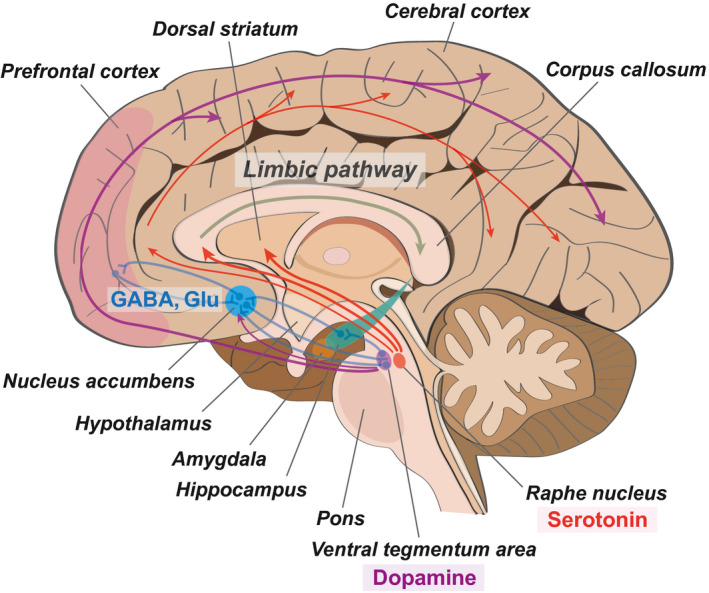

Human neuroimaging studies and studies using animal models have reported that depression results from functional impairments in connections between various brain regions 11 , 12 and that it is involved in the alteration of brain structures 13 (Figure 1). Such studies have also reported that depression is associated with alterations in the structure and functional morphology, as well as the modulation of cellular factors, such as transcription factors, in affected brain regions. 12 , 14 The nucleus accumbens is considered the main regulation center of neuronal circuits implicated in depression. 15 , 16 The nucleus accumbens integrates limbic and cortical information from the prefrontal cortex, ventral hippocampus, and the amygdalar region. 17 Depression‐related brain regions also include the dorsal and medial prefrontal cortices, insular lobe, orbitofrontal cortex, amygdala, hippocampus, and cingulate cortex. 18 , 19 , 20 Decreases in metabolism, in these brain regions, promote the onset of depression and greatly accelerate its progression. 21 , 22 Previous studies have reported that decreases in metabolism, accompanied by reductions in blood flow, are positively correlated with reduced brain volume in these brain regions and with depression. 18 , 19 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26

FIGURE 1.

The neuroanatomical image of depression. This schematic image presents the important neurotransmitter pathway and the neuronal connection between different brain regions in depression. The nucleus accumbens plays as a critical connection hub in depression‐related brain regions. GABA (gamma‐aminobutyric acid) and Glu (glutamate), the neurotransmitters, contribute to the connective signal between the nucleus accumbens and the prefrontal cortex. Serotonin, which is secreted from the raphe nucleus of the brain stem, contributes to the limbic pathway and finally affects the hippocampus, related to cognitive function. Dopamine, another neurotransmitter, which is secreted from the ventral tegmentum area of the brain stem, influences the whole cerebral cortex region in the brain including the prefrontal cortex. See texts for the details. Red arrows indicate the serotonin pathway, and purple arrows indicate the dopamine pathway. Blue lines show the neuronal connection between different brain regions

Dopaminergic neuron in the ventral tegmental area mainly produces dopamine and projects to other brain areas including the striatum and mesolimbic reward pathways related to pain relief center (Figure 1). Dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area are key to mediate stress response. 27 Also, dopamine neuron in pars compacta of substantia nigra contributes to cortico‐basal ganglia‐thalamocortical circle. 27 , 28 Generally, pain contributes to various brain regions, such as the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, dorsal and ventral striatum, and amygdala. 29 Dopamine projected to nucleus accumbens could block physical somatosensory pain. 30

Serotonin neuron from raphe nucleus projects to thalamus, limbic pathway, and prefrontal cortical regions and affects depressive‐like behaviors such as anxiety (Figure 1). 31 Serotonin influences the activity of food eating, motor function, and anxiety feeling. 32

Nucleus accumbens has glutamatergic neurons and GABAergic neurons, and is linked to depressive behavior‐related brain regions such as the ventral tegmental area, prefrontal cortex, and striatum (Figure 1). 33 , 34 Glutamatergic neurons in the nucleus accumbens project to the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, and basal ganglia, and influence mood and anxiety feeling. 35 GABAergic neurons in the nucleus accumbens project to the prefrontal cortex, thalamus, hippocampus, and amygdala and affect the mesocorticolimbic reward system. These neurons regulate dopamine release and reward system, and contribute to memory function by activating the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. 36 , 37

Based on these findings, many researchers have endeavored to identify meaningful biomarkers for depression, in order to diagnose depression and identify its stage of progression. Suggested biomarkers include peripheral blood‐based biomarkers, 38 pro‐inflammatory factors, 39 , 40 , 41 neurotrophic factors, 42 , 43 vascular endothelial growth factor, 44 neurotransmitters, 45 lipid profile, 46 and hypothalamus pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis biomarkers, including cortisol. 47 In particular, epigenetic markers may be key to characterize the pathology of depression, because epigenetic alterations lead to change in the production of proteins related to depressive behavior. 48 Some studies have demonstrated that the accelerated shortening of telomeres is related to stress, 49 , 50 anxiety, 51 and depressive‐like behavior. 52 Other researchers have emphasized the strong contribution of genetic factors to the pathogenesis of depression and individuals’ susceptibility to it. 53 However, it has not been possible to identify predictors of any value at the onset of depression or during its later stages, until now. This is because depression is a biologically heterogeneous psychiatric disease that is associated with a diverse array of potential causes and symptoms. These include anxiety, chronic stress, traumatic experiences, neurochemical reconfigurations, and genetic susceptibility.

One study has also reported that the brains of depressed individuals are commonly under oxidative stress resulting from the overproduction of reactive oxygen species. Further, damage to proteins, lipids, and cell DNA was observed, as was cell death. 54 Other studies have suggested changes in growth factors and inflammatory proteins and stress‐related enzymes and protein interaction system in the depressive brain. 55 , 56 By combining knowledge from these and other studies, it may be possible to identify biomarkers that can be used to make specific, reliable predictions regarding the course of depression. In turn, these predictions could shape the development of suitable, individualized treatments for patients with depression. The detection of early changes in the brains of patients with depression could allow us to better manage the progression of depressive symptoms.

2. DIVERSE ANIMAL MODELS FOR THE STUDY OF DEPRESSION

In order to study the neural mechanisms underlying depression, researchers have developed various animal models for depression. These include a model emphasizing unpredictable chronic stress exposure, 57 the learned helplessness model, 58 a model emphasizing the role of depression induction via the exogenous administration of glucocorticoids, 59 the olfactory bulbectomy depression model, 60 the social defeat model, 61 and a model emphasizing genetic manipulation. 9 , 62 , 63 These models have shown depressive‐like behavior similar to that in human patients with depression. However, each animal model of depression has advantages and disadvantages and accounts for slightly different depression symptoms. 64 Thus, a comprehensive review and analysis of each animal model would be helpful for future research. We outlined the differences between these depression models which may help other researchers to choose a suitable animal model for the study of depression (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Differences between the depression models.

| Inducing factors | Applicable human symptom | |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic mild stress | Congener odor, predator odor, cage tiling, sawdust change, confinement | Sleep disturbance, depressive‐like behavior, reward response, anhedonia |

| Chronic social defeat | Visual stress, olfactory stress, physical contract | Reduction of locomotor activity, reduction of enthusiastic behavior, anxiety, submissive behavior, social avoidance, reduction of food eating |

| Physical pain | Physical pain (spared nerve injury) | Neuropathic and nociceptive pain |

| Learned helplessness | Electronic stress, continuous involuntary movement | Symptoms of traumatic stress, comorbid major depression |

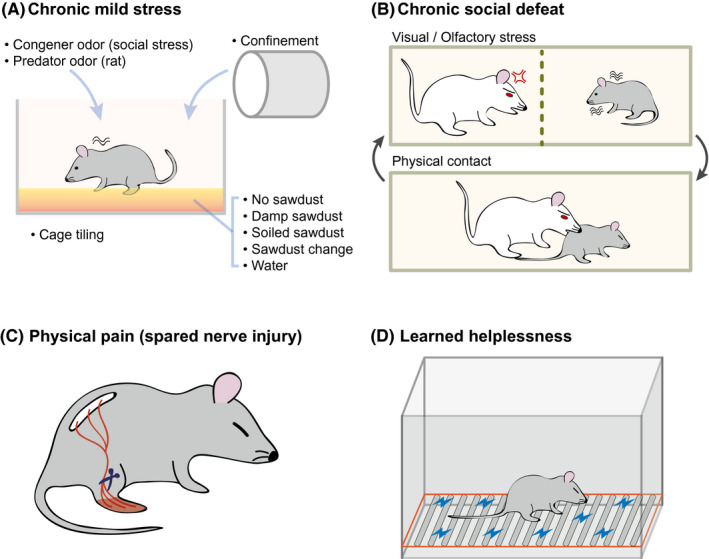

Previous studies have reported on the neuropathology of depression based on various animal models (Figure 2). There are public resources that analyzed the transcriptomic profile for each animal model of depression. For the comparison of transcriptome among diverse depression models and provide easy access to these data, we obtained the RNA sequencing data and calculated gene expression levels (Supplementary Figure 1). 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 These data include the profiling of changes in gene expression in several brain regions, including the prefrontal cortex, hypothalamus, and nucleus accumbens, which are related to the progression of depression, as described above (Table [Link], [Link], [Link], [Link], [Link].) For each depression model, we reviewed the pathophysiology of each model and presented the functional changes based on gene expression for these brain regions as described below.

FIGURE 2.

Experimental models for the study of depression. (A) Chronic mild stress. In this model, the mice are exposed to a series of low‐intensity stressors at unpredictable times for 9 weeks. (B) Chronic social stress. In this model, depression is induced over 10 days by directly exposing the experimental mouse to a larger and aggressive mouse for 5 minutes a day and then housing across a transparent barrier to sustain sensory contact. (C) Physical pain. A spared nerve injury is surgically inflicted, resulting in depressive behaviors due to persistent neuropathic pain. (D) Learned helplessness. The mouse is exposed to unpredictable and inescapable electric footshocks for two consecutive days, after which the mouse shows a defect in its escape behavior and depressive symptoms

2.1. Chronic mild stress model

Chronic mild stress is the most common cause of depressive mood disorders. It results in multiple physiological changes in the brain, including the alteration of corticosterone regulation through the HPA axis, impaired neurogenesis, synaptic dysfunction, and gene expression changes. 69 , 70 , 71 It also induces behavioral changes including depressive‐like behavior, a reduction in the reward response, and sleep disturbances. 72 , 73 Several studies showed that animals exposed to repetitive stress display behavioral changes in open field behavior tests 57 and a decrease in saccharin or sucrose fluid consumption, which is considered indicative of anhedonia. 74 , 75 It was also shown that chronic, uncontrollable stress contributes to the impairment of the brain stimulation reward system. 76 Therefore, these reports suggest that the chronic stress animal model can be used to study depressive neuropathology, 77 and several studies used this model for the test of therapeutic targets to treat the depressive disorder. 78 , 79

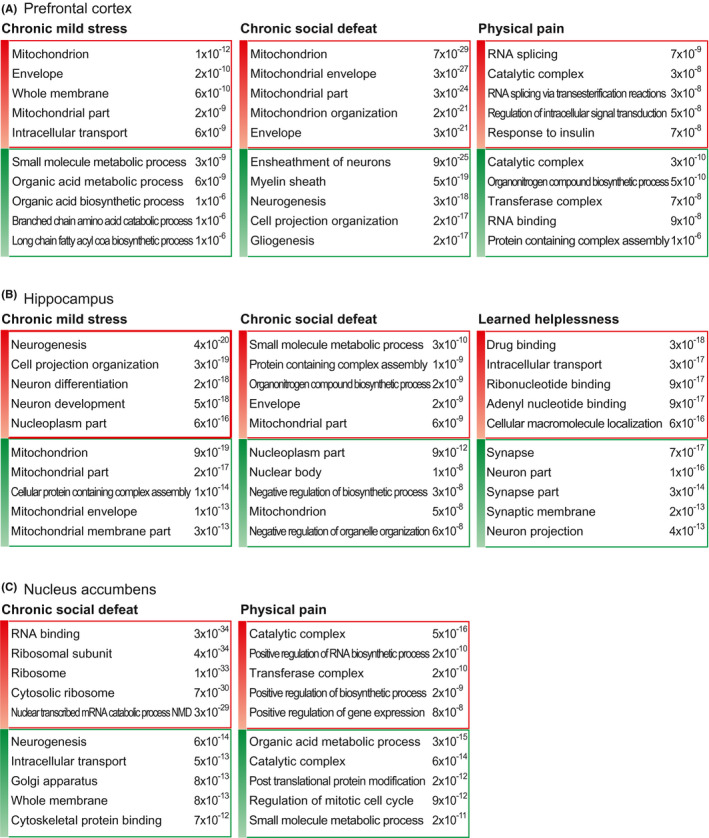

In the mouse model of chronic mild stress, the mice are subjected to unpredictable mild psychosocial stressors for 9 weeks (Figure 2A). 80 From the transcriptome data, many genes showed marked expression changes in brain region including the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, in chronic mild stress animal models (Table S2). 65 Interestingly, the gene ontology (GO) terms related to mitochondria and membranes were enriched in the increased genes group, for the prefrontal cortex, but the same terms were identified in the decreased genes group, for the hippocampus (Figure 3A,B, and Table S6). Related to this result, many studies have shown the connection between mitochondria and depression. 81 , 82 Moreover, the GO terms related to neurogenesis were enriched in the increased genes group, for the hippocampus. Neurogenesis may be altered in animals with chronic stress, as suggested above. 71

FIGURE 3.

Gene ontology analysis of differentially expressed gene groups for each model. First, we selected the top 10000 genes for each model, based on their average signal (FPKM) from RNA sequencing data. If there was any sample with an FPKM value of zero, we removed the genes from further analysis. We selected the top 200 increased (red color box) and decreased genes (green color box) based on their fold changes between the depression model mouse and its corresponding control mouse. We then used these gene groups for gene ontology (GO) analysis with MSigDB (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/). Based on the p‐value, we selected the top 20 GO terms (Supplementary Table 6). We present the most significant five terms in this figure

2.2. Chronic social defeat model

The chronic social defeat animal model has been used to study the pathology of depression and its underlying mechanisms. 83 , 84 The chronic social defeat model is characterized by decreases in locomotor activity, 85 reductions in enthusiastic and aggressive behavior, 86 and increases in submissive behavior and anxiety, 87 as is observed in humans with depression. These symptoms ultimately lead to an increased risk of depression progression. 61 Furthermore, morphologically, the chronic social defeat model featured a reduction in neuronal cell proliferation and a decrease in hippocampus volume. 88 , 89 It was also demonstrated that the chronic social defeat model could alter reward circuity and cause changes in the brain, associated with increased susceptibility to engaging in depressive behavior. 90 Moreover, the chronic social defeat model altered the activity of dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area and ultimately resulted in social avoidance and a reduced preference for sucrose, as is expected in depression pathology. 33 , 91 , 92 Other studies also showed that chronic social defeat stress leads to functional and structural changes in neural circuitry. 12 , 84 In particular, it was demonstrated that the ventral hippocampus and nucleus accumbens were more susceptible to stress from chronic social defeat than was the prefrontal cortex. 66

In the previous work, it was established that chronic social defeat stress induces susceptible and resilient phenotypes in a ratio of 2 to 1, respectively. 84 The susceptible phenotype showed enduring social avoidance, and the resilient phenotype exhibited a tendency of social interaction similar to control mice. Therefore, the expression data of susceptible phenotype were only used for the following analysis. Based on the transcriptome of the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, nucleus accumbens in the chronic social defeat model 66 (Table S3), the result of GO analysis for each gene group is presented (Figure 3 and Table S6). In the increased genes group, the GO terms related to mitochondria were enriched for the prefrontal cortex (Figure 3A). Moreover, the mitochondrion term was also detected in the decreased genes group for the hippocampus. These results are quite similar to those observed in the chronic mild stress model. However, the terms related to neurogenesis and the myelin sheath were enriched in the decreased genes group for the prefrontal cortex in the chronic social defeat model. Some of these terms were identified in the increased genes group for the hippocampus in the chronic mild stress model (Figure 3A,B). Further, the small molecule metabolic process term was the most highly enriched in the increased genes group for the hippocampus in the chronic social defeat model. The same term was the most highly enriched in the decreased genes group for the prefrontal cortex in the chronic mild stress model. We suggest that chronic mild stress and chronic social defeat models have both common and opposite molecular alterations in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, respectively. For the nucleus accumbens, in the chronic social defeat model, the terms related to RNA and ribosomes were included in the increased genes group while those related to neurogenesis and membranes were included in the decreased genes group (Figure 3C). Because the neurogenesis was decreased both in the prefrontal cortex and the nucleus accumbens in this model, it is reasonable to expect that a similar molecular change, related to decreased neurogenesis, occurs in these areas.

2.3. Physical pain model

Physical pain is another major cause of depression. Neuropathic and nociceptive pain, especially, increase the risk of developing depression. 93 , 94 Approximately one‐fifth of the general population currently suffers from chronic pain. 95 Based on these epidemiological data, we assume that many people are likely to have depressive symptoms due to physical pain. Specifically, pain caused by damage to sensory nerve pathways has been shown to influence depressive moods and to be involved in neuronal cell death at brain regions linked to depression, including the insular lobe, prefrontal cortex, thalamus, hippocampus, anterior cingulate, and amygdala. 96

It was reported that the prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens experience neuronal cell death during pain, which subsequently led to the development of depression. 97 The nucleus accumbens is connected to several brain regions related to depressive‐like behavior and pain regulation, including the ventral tegmental area, thalamus, prefrontal cortex, and amygdala 33 , 34 (Figure 1). Several neuroimaging studies have demonstrated that patients suffering from chronic physical pain differed from healthy individuals in terms of activity in the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex, which play a role in reward processes. 98 , 99 , 100 Synaptic dysfunction was also reported in the prefrontal cortex, due to neuropathic pain, in the relevant animal model. 34 , 101 , 102 It has also been found that chronic physical pain is strongly associated with areas ranging from the ventromedial prefrontal cortex to the periaqueductal gray. This region represents the control center for descending sensory pain modulation and has pain‐reducing enkephalin‐producing cells in humans 103 and rodents. 104 Thus, chronic pain and depression show common changes in neuroplasticity mechanisms and are strongly linked to each other. The physical pain model can provide more understandable information toward developing treatments for depression.

The GO analysis using the transcriptome of the prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens in the chronic pain mouse model 2.5 months after the injury was performed 67 (Figure 3A,C, and Tables [Link], [Link]). Interestingly, the GO term “catalytic complex” was enriched both in the increased and decreased genes groups for the prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens. However, there was no notable overlap of GO terms between the physical pain model and other models. This maybe is because the physical pain model is a model of depression induced by physical surgery, whereas psychological stimulation is induced in the other depression models (Figure 2).

2.4. Learned helplessness model

The learned helplessness model has been used to make predictions in cases of depression because it accounts for the symptoms of traumatic stress disorder and comorbid major depression. 105 , 106 Learned helplessness features symptoms of depression that affect neurochemical and molecular processes. These include increased inflammation and the cell death of norepinephrine neurons in the locus coeruleus region, leading to depressive behavioral consequences. 107

In the learned helplessness mice model, 360 scrambled electric footshocks (0.15 mA) with varying duration (1–3 seconds) and interval (1–15 seconds) are treated for two consecutive days. 108 From the GO analysis of the transcriptome from the learned helplessness model, 68 the most enriched terms in the decreased genes group, for the hippocampus, included those related to the synapse (Figure 3B, and Table [Link], [Link]). A previous study reported on the remodeling of synapses in the learned helplessness depression model. 109 However, no GO terms that were enriched in the learned helplessness model were identified in the GO analysis of the hippocampus in other depression models (Figure 3B). We expect that this depression model is characterized by different molecular changes in the hippocampus, compared with other depression models including the chronic mild stress and chronic social defeat models.

Based on the description above, it is obvious that there are commonalities and differences across the many animal models of depression, in terms of changes in gene expression profiles and depressive pathology, in each brain region. One of the notable conclusions from the GO analysis is that the difference in gene expression among depression models is greater than that among tissues that we analyzed such as the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and nucleus accumbens (Figure S2). Thus, although there were many functional terms commonly affected across the different models, our findings indicate that we should consider the difference among the depression animal models, and that it is important to choose a proper model to study depressive disorder. We found that chronic mild stress and chronic social defeat models show very similar molecular changes for the gene group with the greatest changes in gene expression. In contrast, the physical pain model had no specific terms in common with the other depression models. This suggests that the selection of a suitable model is required based on the type of depressive disorder that the researcher wants to study.

3. COMMONLY CHANGED GENES AMONG DIFFERENT DEPRESSION MODELS

There were considerable differences, in terms of changes in gene expression, among the depression models. To offer a list of commonly altered genes among these models, we cross‐compared the gene groups which were significantly altered for each model (Figure S3 and Table S7). Among the models compared, the chronic mild stress and chronic social stress models had the most genes in common, as was expected based on the common GO terms shared between these two depression models (Figure 3 and Figure S3). Heat shock protein family B (small) member 11 (Hspb11) was the only gene commonly decreased in the prefrontal cortex across three depression models (Figure S3A). Interestingly, the HSPB11 locus was reported as one of the most highly hypermethylated regions associated with major depressive disorder. 110 Because protein misfolding and aggregation are observed in a diverse array of neuronal disorders, we expect that Hspb11 also plays a role in the pathology of depression. 111

Among some of the other genes commonly detected across two depression models, there were previous reports which showed the roles of those genes in depression. Neuronal PAS domain protein 4 (Npas4), whose expression was decreased in the prefrontal cortex in the chronic social stress and physical pain models, was reported to play a critical role in depressive behavior, in a study using knockout mice (Figure S3A). 112 A recent co‐expression analysis suggested that ATP5G1 is associated with major depressive disorder, 113 and that a functional polymorphism in the promoter of XBP1 was reported to be associated with depressive episodes 114 (Figure S3B). It was also shown that hippocampal SPARC, which was included as an increased gene in the prefrontal cortex, regulated depression‐related behavior 115 (Figure S3B). Among the other genes, there was a report that the G protein regulated inducer of neurite outgrowth 1 (Gprin1) gene is involved in neurite outgrowth 116 and that YTH domain family 2 (Ythdf2) is linked to the control of neuronal development. 117 However, the relationship of these genes with depression is still unknown (Figure S3C,F). Interestingly, timeless interacting protein (Tipin) was identified as a commonly decreased gene in the prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens, in both the chronic social stress model and the physical pain model.

As described above, several genes were commonly altered across the different depression models. However, most differentially expressed genes were included in one group exclusively. Therefore, in addition to the study of common genes, the elucidation of the function of these genes is necessary to identify the differences between the depression models. We also note that the change of gene expression in different brain regions is not enough. Since there may be differences in gene expression patterns for each cell type, it is necessary to analyze the difference in expression patterns between cell types (stimulatory, inhibitory, or modulatory neurons) in each brain region. This process will be helpful to get a comprehensive understanding of the pathology of depressive disorder.

4. CONCLUSION

The review of previous studies and the additional analysis presented above show the commonalities and differences between depression models that have widely been used in studies of depressive disorder. These models are influenced by different environmental and physical factors and show slightly different neuropsychiatric features. However, we observed that these diverse depression animal models share altered genes related to the aggravation of neuroinflammation and synaptic dysfunction. On the other hand, it also should be noted that changes in gene expression are generally quite different across the depression models. Consequently, we suggest that researchers must consider the differences between the models when deciding which depression model best fits their purposes. Our analysis could contribute to informing such decisions. Further, a more in‐depth research is necessary to identify the animal model of depression that is most comparable to human patients with depression.

CONFLICT INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y‐K. K.: methodology. J. S.: formal analysis. J. S. and Y‐K. K.: conceptualization, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

Supporting information

Table S1

Table S2

Table S3

Table S4

Table S5

Table S6

Table S7

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Not applicable.

Funding information

This study was funded by grants from the Basic Science Research Program, through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF; NRF‐2019R1F1A1054111 to JS and NRF‐2018R1A2B6001104 and NRF‐2019R1A4A1028534 to Y‐KK).

Contributor Information

Juhyun Song, Email: juhyunsong@chonnam.ac.kr.

Young‐Kook Kim, Email: juhyunsong@chonnam.ac.kr.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Andrade L, Caraveo‐Anduaga JJ, Berglund P, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive episodes: results from the International Consortium of Psychiatric Epidemiology (ICPE) Surveys. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003;12(1):3‐21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hasler G, Drevets WC, Manji HK, Charney DS. Discovering endophenotypes for major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(10):1765‐1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brigitta B. Pathophysiology of depression and mechanisms of treatment. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2002;4(1):7‐20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gaiteri C, Ding Y, French B, Tseng GC, Sibille E. Beyond modules and hubs: the potential of gene coexpression networks for investigating molecular mechanisms of complex brain disorders. Genes Brain Behav. 2014;13(1):13‐24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee P, Zhang M, Hong JP, et al. Frequency of painful physical symptoms with major depressive disorder in asia: relationship with disease severity and quality of life. J Clin Psychiatr. 2009;70(1):83‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aguera‐Ortiz L, Failde I, Mico JA, Cervilla J, Lopez‐Ibor JJ. Pain as a symptom of depression: prevalence and clinical correlates in patients attending psychiatric clinics. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1–2):106‐112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van Loo HM, de Jonge P, Romeijn JW, Kessler RC, Schoevers RA. Data‐driven subtypes of major depressive disorder: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2012;10:156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Vos S, Wardenaar KJ, Bos EH, Wit EC, de Jonge P. Decomposing the heterogeneity of depression at the person‐, symptom‐, and time‐level: latent variable models versus multimode principal component analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Willner P, Belzung C. Treatment‐resistant depression: are animal models of depression fit for purpose? Psychopharmacology. 2015;232(19):3473‐3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li BJ, Friston K, Mody M, Wang HN, Lu HB, Hu DW. A brain network model for depression: From symptom understanding to disease intervention. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2018;24(11):1004‐1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Christoffel DJ, Golden SA, Walsh JJ, et al. Excitatory transmission at thalamo‐striatal synapses mediates susceptibility to social stress. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(7):962‐964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bagot RC, Parise EM, Pena CJ, et al. Ventral hippocampal afferents to the nucleus accumbens regulate susceptibility to depression. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen ZQ, Du MY, Zhao YJ, et al. Voxel‐wise meta‐analyses of brain blood flow and local synchrony abnormalities in medication‐free patients with major depressive disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015;40(6):401‐411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ding Y, Chang LC, Wang X, et al. Molecular and genetic characterization of depression: overlap with other psychiatric disorders and aging. Mol Neuropsychiatry. 2015;1(1):1‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schlaepfer TE, Cohen MX, Frick C, et al. Deep brain stimulation to reward circuitry alleviates anhedonia in refractory major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(2):368‐377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Epstein J, Pan H, Kocsis JH, et al. Lack of ventral striatal response to positive stimuli in depressed versus normal subjects. Am J Psychiatr. 2006;163(10):1784‐1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goto Y, Grace AA. Limbic and cortical information processing in the nucleus accumbens. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31(11):552‐558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lorenzetti V, Allen NB, Fornito A, Yucel M. Structural brain abnormalities in major depressive disorder: a selective review of recent MRI studies. J Affect Disord. 2009;117(1–2):1‐17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Davidson RJ, Irwin W, Anderle MJ, Kalin NH. The neural substrates of affective processing in depressed patients treated with venlafaxine. Am J Psychiatr. 2003;160(1):64‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sheline YI, Gado MH, Price JL. Amygdala core nuclei volumes are decreased in recurrent major depression. NeuroReport. 1998;9(9):2023‐2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rigucci S, Serafini G, Pompili M, Kotzalidis GD, Tatarelli R. Anatomical and functional correlates in major depressive disorder: the contribution of neuroimaging studies. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11(2 Pt 2):165‐180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Desmyter S, van Heeringen C, Audenaert K. Structural and functional neuroimaging studies of the suicidal brain. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(4):796‐808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mayberg HS, Brannan SK, Tekell JL, et al. Regional metabolic effects of fluoxetine in major depression: serial changes and relationship to clinical response. Biol Psychiat. 2000;48(8):830‐843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kumar A, Bilker W, Jin Z, Udupa J. Atrophy and high intensity lesions: complementary neurobiological mechanisms in late‐life major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22(3):264‐274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schweitzer I, Tuckwell V, Ames D, O'Brien J. Structural neuroimaging studies in late‐life depression: a review. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2001;2(2):83‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bremner JD, Vythilingam M, Vermetten E, et al. Reduced volume of orbitofrontal cortex in major depression. Biol Psychiat. 2002;51(4):273‐279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Xie JY, Qu C, Patwardhan A, et al. Activation of mesocorticolimbic reward circuits for assessment of relief of ongoing pain: a potential biomarker of efficacy. Pain. 2014;155(8):1659‐1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yager LM, Garcia AF, Wunsch AM, Ferguson SM. The ins and outs of the striatum: role in drug addiction. Neuroscience. 2015;301:529‐541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bushnell MC, Ceko M, Low LA. Cognitive and emotional control of pain and its disruption in chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(7):502‐511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Navratilova E, Xie JY, Okun A, et al. Pain relief produces negative reinforcement through activation of mesolimbic reward‐valuation circuitry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(50):20709‐20713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Arango V, Underwood MD, Mann JJ. Serotonin brain circuits involved in major depression and suicide. Prog Brain Res. 2002;136:443‐453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dolzani SD, Baratta MV, Amat J, et al. Activation of a habenulo‐raphe circuit is critical for the behavioral and neurochemical consequences of uncontrollable stress in the male rat. eNeuro. 2016;3(5):ENEURO.0229‐16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chaudhury D, Walsh JJ, Friedman AK, et al. Rapid regulation of depression‐related behaviours by control of midbrain dopamine neurons. Nature. 2013;493(7433):532‐536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Navratilova E, Xie JY, Meske D, et al. Endogenous opioid activity in the anterior cingulate cortex is required for relief of pain. J Neurosci. 2015;35(18):7264‐7271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Scofield MD, Heinsbroek JA, Gipson CD, et al. The nucleus accumbens: mechanisms of addiction across drug classes reflect the importance of glutamate homeostasis. Pharmacol Rev. 2016;68(3):816‐871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang L, Shen M, Yu Y, et al. Optogenetic activation of GABAergic neurons in the nucleus accumbens decreases the activity of the ventral pallidum and the expression of cocaine‐context‐associated memory. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17(5):753‐763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang T, Deyama S, Domoto M, et al. Activation of GABAergic neurons in the nucleus accumbens mediates the expression of cocaine‐associated memory. Biol Pharm Bull. 2018;41(7):1084‐1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jani BD, McLean G, Nicholl BI, et al. Risk assessment and predicting outcomes in patients with depressive symptoms: a review of potential role of peripheral blood based biomarkers. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Maes M, Leonard BE, Myint AM, Kubera M, Verkerk R. The new ‘5‐HT’ hypothesis of depression: cell‐mediated immune activation induces indoleamine 2,3‐dioxygenase, which leads to lower plasma tryptophan and an increased synthesis of detrimental tryptophan catabolites (TRYCATs), both of which contribute to the onset of depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(3):702‐721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Eyre HA, Air T, Pradhan A, et al. A meta‐analysis of chemokines in major depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;68:1‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Strawbridge R, Arnone D, Danese A, Papadopoulos A, Herane Vives A, Cleare AJ. Inflammation and clinical response to treatment in depression: A meta‐analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25(10):1532‐1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bocchio‐Chiavetto L, Bagnardi V, Zanardini R, et al. Serum and plasma BDNF levels in major depression: a replication study and meta‐analyses. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11(6):763‐773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Molendijk ML, Spinhoven P, Polak M, Bus BA, Penninx BW, Elzinga BM. Serum BDNF concentrations as peripheral manifestations of depression: evidence from a systematic review and meta‐analyses on 179 associations (N=9484). Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19(7):791‐800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Warner‐Schmidt JL, Duman RS. VEGF as a potential target for therapeutic intervention in depression. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8(1):14‐19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kaufman J, DeLorenzo C, Choudhury S, Parsey RV. The 5‐HT1A receptor in major depressive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26(3):397‐410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Srikanthan K, Feyh A, Visweshwar H, Shapiro JI, Sodhi K. Systematic review of metabolic syndrome biomarkers: a panel for early detection, management, and risk stratification in the west virginian population. Int J Med Sci. 2016;13(1):25‐38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Stetler C, Miller GE. Depression and hypothalamic‐pituitary‐adrenal activation: a quantitative summary of four decades of research. Psychosom Med. 2011;73(2):114‐126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sun H, Kennedy PJ, Nestler EJ. Epigenetics of the depressed brain: role of histone acetylation and methylation. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(1):124‐137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shalev I, Moffitt TE, Sugden K, et al. Exposure to violence during childhood is associated with telomere erosion from 5 to 10 years of age: a longitudinal study. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(5):576‐581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Epel ES, Blackburn EH, Lin J, et al. Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(49):17312‐17315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Okereke OI, Prescott J, Wong JY, Han J, Rexrode KM, De Vivo I. High phobic anxiety is related to lower leukocyte telomere length in women. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wolkowitz OM, Mellon SH, Epel ES, et al. Leukocyte telomere length in major depression: correlations with chronicity, inflammation and oxidative stress–preliminary findings. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shi J, Potash JB, Knowles JA, et al. Genome‐wide association study of recurrent early‐onset major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16(2):193‐201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Siwek M, Sowa‐Kucma M, Dudek D, et al. Oxidative stress markers in affective disorders. Pharmacol Rep. 2013;65(6):1558‐1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hacimusalar Y, Esel E. Suggested biomarkers for major depressive disorder. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2018;55(3):280‐290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Miller AH, Maletic V, Raison CL. Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol Psychiat. 2009;65(9):732‐741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Katz RJ, Roth KA, Carroll BJ. Acute and chronic stress effects on open field activity in the rat: implications for a model of depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1981;5(2):247‐251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Seligman ME. Learned helplessness. Annu Rev Med. 1972;23:407‐412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gregus A, Wintink AJ, Davis AC, Kalynchuk LE. Effect of repeated corticosterone injections and restraint stress on anxiety and depression‐like behavior in male rats. Behav Brain Res. 2005;156(1):105‐114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Song C, Leonard BE. The olfactory bulbectomised rat as a model of depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29(4–5):627‐647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Huhman KL. Social conflict models: can they inform us about human psychopathology? Horm Behav. 2006;50(4):640‐646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Overstreet DH, Friedman E, Mathe AA, Yadid G. The Flinders Sensitive Line rat: a selectively bred putative animal model of depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29(4–5):739‐759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Krishnan V, Nestler EJ. The molecular neurobiology of depression. Nature. 2008;455(7215):894‐902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Belzung C, Lemoine M. Criteria of validity for animal models of psychiatric disorders: focus on anxiety disorders and depression. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord. 2011;1(1):9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Nollet M, Hicks H, McCarthy AP, et al. REM sleep's unique associations with corticosterone regulation, apoptotic pathways, and behavior in chronic stress in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116(7):2733‐2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bagot RC, Cates HM, Purushothaman I, et al. Circuit‐wide transcriptional profiling reveals brain region‐specific gene networks regulating depression susceptibility. Neuron. 2016;90(5):969‐983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Descalzi G, Mitsi V, Purushothaman I, et al. Neuropathic pain promotes adaptive changes in gene expression in brain networks involved in stress and depression. Sci Signal. 2017;10(471):eaaj1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Li C, Cao F, Li S, Huang S, Li W, Abumaria N. Profiling and co‐expression network analysis of learned helplessness regulated mRNAs and lncRNAs in the mouse hippocampus. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017;10:454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Herman JP, Tasker JG. Paraventricular hypothalamic mechanisms of chronic stress adaptation. Front Endocrinol. 2016;7:137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. McEwen BS, Bowles NP, Gray JD, et al. Mechanisms of stress in the brain. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(10):1353‐1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Hanson ND, Owens MJ, Nemeroff CB. Depression, antidepressants, and neurogenesis: a critical reappraisal. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(13):2589‐2602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sanford LD, Suchecki D, Meerlo P. Stress, arousal, and sleep. Curr Topics Behav Neurosci. 2015;25:379‐410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Willner P. The chronic mild stress (CMS) model of depression: History, evaluation and usage. Neurobiol Stress. 2017;6:78‐93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Katz RJ, Baldrighi G. A further parametric study of imipramine in an animal model of depression. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1982;16(6):969‐972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Willner P, Muscat R, Papp M. Chronic mild stress‐induced anhedonia: a realistic animal model of depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1992;16(4):525‐534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zacharko RM, Bowers WJ, Anisman H. Responding for brain stimulation: stress and desmethylimipramine. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1984;8(4–6):601‐606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Willner P. Validity, reliability and utility of the chronic mild stress model of depression: a 10‐year review and evaluation. Psychopharmacology. 1997;134(4):319‐329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Xu YH, Yu M, Wei H, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 22 is a novel modulator of depression through interleukin‐1beta. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2017;23(11):907‐916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Zhang J, Zhou H, Yang J, et al. Low‐intensity pulsed ultrasound ameliorates depression‐like behaviors in a rat model of chronic unpredictable stress. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2021;27(2):233‐243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Nollet M, Le Guisquet AM, Belzung C. Models of depression: unpredictable chronic mild stress in mice. Curr Protoc Pharmacol. 2013;61:5.65.1–5.65.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Allen J, Romay‐Tallon R, Brymer KJ, Caruncho HJ, Kalynchuk LE. Mitochondria and mood: mitochondrial dysfunction as a key player in the manifestation of depression. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Bansal Y, Kuhad A. Mitochondrial dysfunction in depression. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2016;14(6):610‐618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Bartolomucci A, Palanza P, Costoli T, et al. Chronic psychosocial stress persistently alters autonomic function and physical activity in mice. Physiol Behav. 2003;80(1):57‐67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Krishnan V, Han MH, Graham DL, et al. Molecular adaptations underlying susceptibility and resistance to social defeat in brain reward regions. Cell. 2007;131(2):391‐404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Tidey JW, Miczek KA. Acquisition of cocaine self‐administration after social stress: role of accumbens dopamine. Psychopharmacology. 1997;130(3):203‐212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Meerlo P, Overkamp GJ, Daan S, Van Den Hoofdakker RH, Koolhaas JM. Changes in behaviour and body weight following a single or double social defeat in rats. Stress. 1996;1(1):21‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Crawford LK, Rahman SF, Beck SG. Social stress alters inhibitory synaptic input to distinct subpopulations of raphe serotonin neurons. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2013;4(1):200‐209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Van Bokhoven P, Oomen CA, Hoogendijk WJ, Smit AB, Lucassen PJ, Spijker S. Reduction in hippocampal neurogenesis after social defeat is long‐lasting and responsive to late antidepressant treatment. Eur J Neuorsci. 2011;33(10):1833‐1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Becker C, Zeau B, Rivat C, Blugeot A, Hamon M, Benoliel JJ. Repeated social defeat‐induced depression‐like behavioral and biological alterations in rats: involvement of cholecystokinin. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13(12):1079‐1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Han X, Albrechet‐Souza L, Doyle MR, Shimamoto A, DeBold JF, Miczek KA. Social stress and escalated drug self‐administration in mice II. Cocaine and dopamine in the nucleus accumbens. Psychopharmacology. 2015;232(6):1003‐1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Walsh JJ, Friedman AK, Sun H, et al. Stress and CRF gate neural activation of BDNF in the mesolimbic reward pathway. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(1):27‐29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Friedman AK, Walsh JJ, Juarez B, et al. Enhancing depression mechanisms in midbrain dopamine neurons achieves homeostatic resilience. Science. 2014;344(6181):313‐319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Li X, Hu L. The role of stress regulation on neural plasticity in pain chronification. Neural Plast. 2016;2016:6402942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Li XY, Wan Y, Tang SJ, Guan Y, Wei F, Ma D. Maladaptive plasticity and neuropathic pain. Neural Plast. 2016;2016:4842159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(4):287‐333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Meerwijk EL, Ford JM, Weiss SJ. Brain regions associated with psychological pain: implications for a neural network and its relationship to physical pain. Brain Imaging Behav. 2013;7(1):1‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Baliki MN, Petre B, Torbey S, et al. Corticostriatal functional connectivity predicts transition to chronic back pain. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(8):1117‐1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Hashmi JA, Baliki MN, Huang L, et al. Shape shifting pain: chronification of back pain shifts brain representation from nociceptive to emotional circuits. Brain. 2013;136(Pt 9):2751‐2768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Baliki MN, Geha PY, Fields HL, Apkarian AV. Predicting value of pain and analgesia: nucleus accumbens response to noxious stimuli changes in the presence of chronic pain. Neuron. 2010;66(1):149‐160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Moayedi M, Weissman‐Fogel I, Crawley AP, et al. Contribution of chronic pain and neuroticism to abnormal forebrain gray matter in patients with temporomandibular disorder. NeuroImage. 2011;55(1):277‐286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Massart R, Dymov S, Millecamps M, et al. Overlapping signatures of chronic pain in the DNA methylation landscape of prefrontal cortex and peripheral T cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Alvarado S, Tajerian M, Millecamps M, Suderman M, Stone LS, Szyf M. Peripheral nerve injury is accompanied by chronic transcriptome‐wide changes in the mouse prefrontal cortex. Mol Pain. 2013;9:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Yu R, Gollub RL, Spaeth R, Napadow V, Wasan A, Kong J. Disrupted functional connectivity of the periaqueductal gray in chronic low back pain. Neuroimage Clin. 2014;6:100‐108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Floyd NS, Price JL, Ferry AT, Keay KA, Bandler R. Orbitomedial prefrontal cortical projections to distinct longitudinal columns of the periaqueductal gray in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2000;422(4):556‐578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Hammack SE, Cooper MA, Lezak KR. Overlapping neurobiology of learned helplessness and conditioned defeat: implications for PTSD and mood disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(2):565‐575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Foa EB, Zinbarg R, Rothbaum BO. Uncontrollability and unpredictability in post‐traumatic stress disorder: an animal model. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(2):218‐238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Maier SF, Seligman ME. Learned helplessness at fifty: Insights from neuroscience. Psychol Rev. 2016;123(4):349‐367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Chourbaji S, Zacher C, Sanchis‐Segura C, Dormann C, Vollmayr B, Gass P. Learned helplessness: validity and reliability of depressive‐like states in mice. Brain Res Brain Res Protoc. 2005;16(1–3):70‐78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Hajszan T, Dow A, Warner‐Schmidt JL, et al. Remodeling of hippocampal spine synapses in the rat learned helplessness model of depression. Biol Psychiat. 2009;65(5):392‐400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Zhu Y, Strachan E, Fowler E, Bacus T, Roy‐Byrne P, Zhao J. Genome‐wide profiling of DNA methylome and transcriptome in peripheral blood monocytes for major depression: A Monozygotic Discordant Twin Study. Transl Psychiat. 2019;9(1):215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Stetler RA, Gan Y, Zhang W, et al. Heat shock proteins: cellular and molecular mechanisms in the central nervous system. Prog Neurogibol. 2010;92(2):184‐211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Jaehne EJ, Klaric TS, Koblar SA, Baune BT, Lewis MD. Effects of Npas4 deficiency on anxiety, depression‐like, cognition and sociability behaviour. Behav Brain Res. 2015;281:276‐282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Zeng D, He S, Ma C, et al. Co‐expression network analysis revealed that the ATP5G1 gene is associated with major depressive disorder. Front Genet. 2019;10:703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Grunebaum MF, Galfalvy HC, Huang YY, et al. Association of X‐box binding protein 1 (XBP1) genotype with morning cortisol and 1‐year clinical course after a major depressive episode. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12(2):281‐283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Campolongo M, Benedetti L, Podhajcer OL, Pitossi F, Depino AM. Hippocampal SPARC regulates depression‐related behavior. Genes Brain Behav. 2012;11(8):966‐976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Nordman JC, Kabbani N. An interaction between alpha7 nicotinic receptors and a G‐protein pathway complex regulates neurite growth in neural cells. J Cell Sci. 2012;125(Pt 22):5502‐5513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Li M, Zhao X, Wang W, et al. Ythdf2‐mediated m(6)A mRNA clearance modulates neural development in mice. Genome Biol. 2018;19(1):69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1

Table S2

Table S3

Table S4

Table S5

Table S6

Table S7

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.