Abstract

Objective

To determine the prevalence of physician burnout during the pandemic and differences by gender, ethnicity or sexual orientation.

Design, setting and participants

We conducted a cross-sectional survey (August–October in 2020) of internal medicine physicians at two academic hospitals in Vancouver, Canada.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Physician burnout and its components, emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and personal accomplishment were measured using the Maslach Burnout Inventory.

Results

The response rate was 38% (n=302/803 respondents, 49% women,). The prevalence of burnout was 68% (emotional exhaustion 63%, depersonalisation 39%) and feeling low personal accomplishment 22%. In addition, 21% reported that they were considering quitting the profession or had quit a position. Women were more likely to report emotional exhaustion (OR 2.00, 95% CI: 1.07 to 3.73, p=0.03) and feeling low personal accomplishment (OR 2.26, 95% CI: 1.09 to 4.70, p=0.03) than men. Visible ethnic minority physicians were more likely to report feeling lower personal accomplishment than white physicians (OR 1.81, 95% CI: 1.28 to 2.55, p=0.001). There was no difference in emotional exhaustion or depersonalisation by ethnicity or sexual orientation. Physicians who reported that COVID-19 affected their burnout were more likely to report any burnout (OR: 3.74, 95% CI: 1.99 to 7.01, p<0.001) and consideration of quitting or quit (OR: 3.20, 95% CI: 1.34 to 7.66, p=0.009).

Conclusion

Burnout affects 2 out of 3 internal medicine physicians during the pandemic. Women, ethnic minority physicians and those who feel that COVID-19 affects burnout were more likely to report components of burnout. Further understanding of factors driving feelings of low personal accomplishment in women and ethnic minority physicians is needed.

Keywords: COVID-19, public health, mental health, human resource management, general medicine (see internal medicine)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This survey used a validated burnout instrument, Maslach Burnout Inventory, to measure internal medicine physician burnout during the pandemic.

The study analysed ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation of physicians on burnout and personal accomplishment that is infrequently assessed.

As interventions for reducing burnout are not frequently informed by physician views, we determined which types of interventions to reduce burnout were considered important and explored any differences of these preferences by ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation.

The response rate was somewhat low at 38% but the results did not differ among divisions that had high response rates>50% compared with those that were lower.

Introduction

Burnout is an occupational syndrome consisting of emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and a diminished sense of personal accomplishment from work stress. Physician burnout is increasing from a prevalence of 35%–50% despite ongoing efforts to reduce burnout,1 with a recent meta-analysis indicating a 51% prevalence prior to the pandemic.2 The recent pandemic has placed further strain on physicians due to increased workload, anxiety related to supply of personal protective equipment, and uncertainty about patient care and health services.3 Burnout is a vital issue for physicians and healthcare systems as burnout is associated with worse job performance among physicians, job attrition and is a stronger contributor to medical errors than fatigue.4 Burnout costs the Canadian health system $213 million related to reduced physician work hours.5

Physician burnout may disproportionately affect individuals based on their gender, ethnicity and sexual orientation, although study findings are sparse and inconsistent.6–8 Among women, unequal patient expectations, greater hours spent on child rearing and gender discrimination may contribute to the increased emotional exhaustion experienced relative to men.6 Ethnic minority physicians experience more exclusion, and racial discrimination relative to white physicians7 and sexual minority medical students experience more depression than heterosexual medical students.8 The pandemic may further amplify these structural inequities. The Public Health Agency of Canada reports that women, racialized Canadians and essential workers are disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.9 According to the American Medical Association, COVID-19 exacerbated inequities, not just for patients, but also for physicians.10 These issues may not only impact the prevalence of burnout, but also influence the potential solutions for mitigating burnout.

Thus, we sought to evaluate the prevalence of burnout, determinants, work-to-life conflict, considerations of quitting and views on potential interventions to reduce burnout during the pandemic and to examine whether these measures differed by gender, ethnicity and sexual orientation among physicians who worked in the department of medicine at two academic, tertiary care hospitals in Vancouver, Canada.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional online survey of physician members of the department of medicine at the University of British Columbia at two tertiary care hospital sites. The study reporting followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Checklist.

Participants and setting

All active members of the department of medicine working at two academic, tertiary care hospitals in Vancouver were identified through division email lists. The department of medicine is the largest department in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of British Columbia (803 members with 37% women) and is a mix of academic (114 with 30% women) and clinical faculty. While all participants worked at either or both of the two tertiary care centres, physicians also worked at community hospitals, private practice or hospital ambulatory clinics, and rural or outreach sites. Participants provided informed consent.

Survey

Content experts in physician burnout from the research team developed the survey questions based on the literature on burnout. The online questionnaire was administered using the Qualtrics survey platform (Qualtrics, Provo, Utah) for web and mobile-based administration. The survey was pretested with a representative group of six physicians within the department of medicine to ensure that the questions and formatting were clear. Based on this, wording and the flow of demographic and intervention questions were then modified accordingly.

Demographic and practice characteristics

We collected information on gender (man, woman, non-binary person or prefer not to say), number of children (of any age), age, ethnicity (white, South Asian, Asian or Pacific Islander, or other) and sexual orientation (identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, two-spirited or queer (LGBTQ), or identify as heterosexual). We collected years in practice, specialty including if the specialty was directly responsible for caring for patients with COVID-19 (intensive care or general internal medicine), hours per week spent on clinical, and academic (teaching, research, administrative, medical education) activities, on call duties per month, number of weekend days working in a month, and use of electronic medical records (EMR) systems.

Burnout, consideration of quitting and work-to-life conflict

The Maslach Burnout Inventory—Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel (MBI) was used to assess burnout as this is the most widely used standard to measure burnout for healthcare professionals.11 This validated instrument includes 22 items, each scored from 0 to 6 based on self-reported frequency of the feeling addressed by each item. In addition to providing an overall measure of burnout, the instrument enables the measurement of the three distinct domains of burnout using summated ratings. The emotional exhaustion domain consists of nine items (eg, I feel emotionally drained from my work) for a total score range of 0–54. The depersonalisation domain consists of five items (eg, I do not really care what happens to some patients) for a total score range of 0–30. The personal accomplishment domain consists of eight items (eg, I have accomplished many worthwhile things in this job) for a total score range of 0–48. The presence of physician burnout was defined as an emotional exhaustion score ≥27 or depersonalisation score ≥10, consistent with criteria used in other studies12 and those with scores less than this were considered as not experiencing burnout. We used the same cut-points for defining the presence of emotional exhaustion or not and depersonalisation or not. Feeling low personal accomplishment (defined as a score ≤33) was evaluated separately from overall burnout.12 Evidence linked one-point changes in burnout scores with meaningful differences in self-perceived major medical errors, reductions in work hours and suicidal ideation.13

Respondents were asked if they had ever left a position or considered quitting a position now for any reason. We assessed work-to-life conflict using one item from a national study on burnout among physicians: ‘My work schedule leaves me enough time for my personal/family life’ (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree).14 The presence of work-to life conflict was considered if respondents disagreed with that statement. Physicians were also asked if they felt that the COVID-19 pandemic increased their feelings of burnout (agree, neither agree nor disagree or disagree).

Ratings of interventions to reduce or prevent physician burnout by physicians

Respondents were asked to rate on a scale of 1–10 the importance of various interventions to reduce or prevent burnout. These potential interventions included person-level and organisation-level interventions that were derived from systematic reviews of interventions that were considered to reduce burnout.15–17

Procedures

Electronic links to the questionnaires were emailed from August to October 2020 using updated email lists from the divisions. We employed a modified Dilman approach18 to recruit participants including an initial email-out from the research team followed by two reminders via email. There were no limitations on time to respond. Survey responses were anonymous, and no incentives were provided.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved with this study as it pertained to physicians only. Physicians were involved throughout the study process.

Statistical analysis

Based on these data from a convenience sample, standard descriptive summary statistics were used to characterise the physician respondents, survey scores and ratings of interventions. Separate multivariable logistic regression models were developed to assess associations with overall burnout, burnout subscales (eg, emotional exhaustion vs not and depersonalisation vs not), quitting and work-life conflict. All models included the following explanatory variables: age, gender, ethnicity (dichotomised to white or visible ethnic minority physician due to sample size), sexual orientation, clinical hours, attribution of COVID-19 affecting burnout, division, weekend days worked and on call duties. We tested for the presence of interactions between gender and ethnicity as well as gender and sexual orientation in these models. As these interactions were non-significant, we present the models without the interaction terms. Missing values ranged from 14% to 17.5% across all survey questions (14% missing MBI). From available data, there were no statistically significant differences by division, age, gender, ethnicity or clinical hours worked among those with missing data and those without. Missing values were excluded from analyses (complete case analysis); therefore, our estimates are conservative. All tests were two sided, and the level of significance was 0.05. All analyses were done using STATA V.12.0 (Texas, USA).

Results

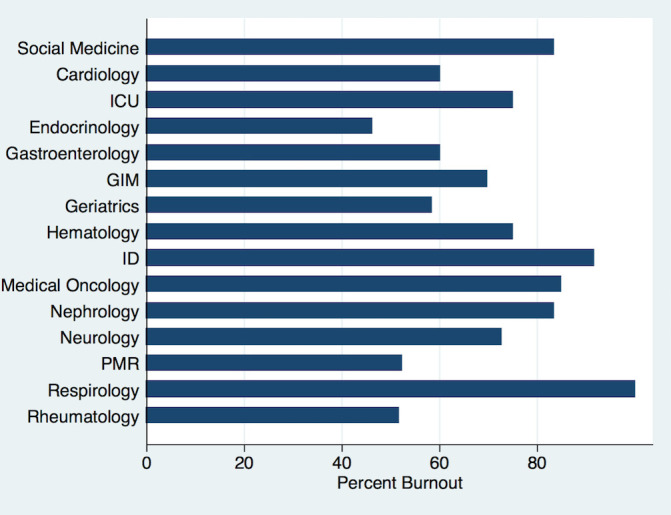

Of the 803 (37% (297/803) women) physicians invited to participate in the questionnaire, we received 302 responses (38% response rate with 31% with complete responses (49% women)). Response rates by division ranged from 13% to 96% (figure 1 and table 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of burnout by division %. ICU, intensive care unit. GIM, general internal medicine, ID, infectious disease, PMR, physical medicine and rehabilitation.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to physician burnout, %(n)*

| Characteristics | No burnout N=79 |

Burnout N=170 |

P value |

| Demographics | |||

| Age | 13.9 (11) | 12.5 (21) | 0.03 |

| 25–35 years | 40.5 (32) | 54.8 (92) | |

| 36–50 years | 29.1 (23) | 29.2 (49) | |

| 51–65 years | 16.4 (13) | 3.6 (6) | |

| 66 years or older | |||

| Women | 44.3 (35) | 52.7 (87) | 0.23 |

| Ethnicity | 0.88 | ||

| White | 62.3 (48) | 70.7 (118) | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 24.7 (19) | 13.2 (22) | |

| South Asian | 7.8 (6) | 7.78 (13) | |

| Other | 5.2 (4) | 8.4 (14) | |

| LGBTQ | 7.6 (6) | 5.4 (9) | 0.32 |

| Children | 0.52 | ||

| No children | 23.1 (18) | 31.1 (52) | |

| 1–2 children | 50 (39) | 47.9 (80) | |

| 3 or more children | 26.9 (21) | 21 (35) | |

| Work characteristics | |||

| Medicine specialty | 0.54 | ||

| General internal medicine | 12.8 (10). | 13.5 (23). | |

| Medical oncology | 6.4 (5) | 16.4 (28) | |

| Neurology | 11.5 (9) | 14.0 (24) | |

| Rheumatology | 18 (14) | 8.8 (15) | |

| PMR | 12.8 (10) | 6.4 (11) | |

| ICU | 5.1 (4) | 7.0 (12) | |

| Cardiology | 5.1 (4) | 3.5 (6) | |

| Endocrinology | 9 (7) | 3.5 (6) | |

| Gastroenterology | 5.1 (4) | 3.5 (6) | |

| Infectious diseases | <4 | 6.4 (11) | |

| Social medicine† | <4 | 2.9 (5) | |

| Other divisions | 10.1 (8) | 13.5 (23) | |

| Divisions primarily responsible for COVID-19 care | 17.7 (14) | 20.5 (35) | 0.61 |

| Appointment | 0.86 | ||

| Clinical | 92.4 (73) | 90.6 (155) | |

| Research | 27.9 (22) | 28.7 (49) | |

| Medical education | 31.7 (25) | 39.2 (67) | |

| Administration | 15.2 (12) | 25.2 (43) | |

| Clinical duty hours | 0.04 | ||

| >40 hours/week | 52.1 (38) | 46.5 (72) | |

| >60 hours/week | 8.2 (6) | 21.9 (34) | |

| Weekend days working/month | 0.27 | ||

| None | 25.3 (20) | 17.8 (30) | |

| 1–2 | 44.3 (35) | 52.1 (88) | |

| 3–4 | 25.3 (20) | 19.5 (33) | |

| 5 or more | 5.1 (4) | 10.7 (18) | |

| Call days/month | 0.9 | ||

| None | 20.5 (16) | 15.8 (26) | |

| 1–3 | 47.4 (37) | 55.8 (92) | |

| 4 or more | 32.1 (25) | 28.5 (47) | |

| View COVID-19 as affecting burnout | 45.6 (36) | 75.2 (127) | <0.0001 |

*14–17.5% missing data excluded.

†Social Medicine is a new division that includes a focus on addictions and social determinants of health.

ICU, intensive care unit; LGBTQ, lesbian, gay, bisexual, two-spirited or queer; PMR, physical medicine and rehabilitation.

As presented in table 1, most respondents with complete data were between ages 35 and 50 years and had children. Almost half were women (122/249), no persons identified as non-binary and 2% (6/249) of respondents preferred not to provide their gender. Almost one-third (78/249) of physician respondents identified as a visible ethnic minority. There were 6% (15/249) of individuals who identified as LGBTQ. While almost all respondents worked clinically, 28% (70/249) included research in their portfolio, 37% (93/249) conducted medical education work and 22% (55/249) also carried out administrative work.

Overall burnout prevalence

The prevalence of burnout was 68% among all respondents, 71% (86/121) among women and 64% (75/117) among men (p=0.25). Burnout was reported by 60% (9/15) of persons who identified as LGBTQ. The prevalence of burnout by ethnicity was: white physicians 71% (117/165), South Asian physicians 68% (13/19), physicians identifying as other ethnicities 78% (14/18) and Asian and Asian Pacific Islander physicians 54% (22/41) (p=0.88). Burnout was highest in those who were 36–50 years at 74% (93/125) and lower with increasing age categories; 51–65 years was 68% (48/71) and 66 years and older had a prevalence of burnout of 32% (6/19) (p=0.03). The prevalence of burnout ranged from 46% to 100% across divisions (figure 1). Divisions with a response rate of >55% had a similar prevalence of burnout compared with divisions with lower response rates (65% vs 70%, p=0.40). Burnout was not significantly different in those divisions primarily responsible for caring for patients with COVID-19 compared with other divisions (71% (35/49) vs 68% (135/200), p=0.60).

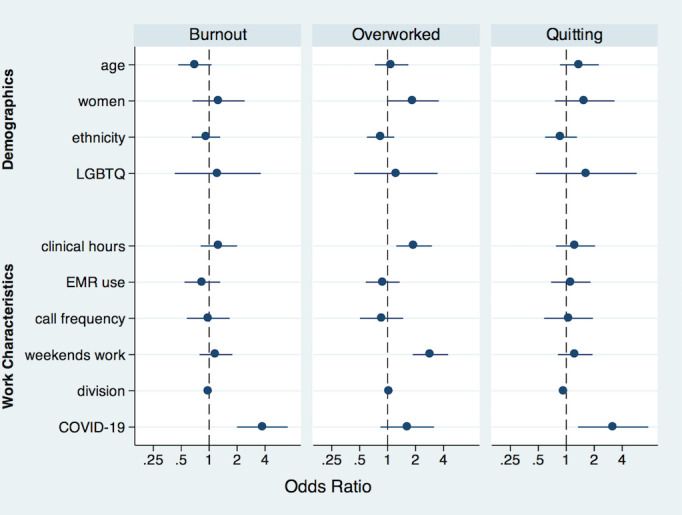

As discerned in table 1, from the bivariable analysis of demographic and work characteristics with burnout, only age and clinical work hours were significantly associated. However, there were no demographic or work characteristics associated with overall burnout in the multivariable analyses (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Multivariate association of burnout, work-life conflict and consideration of quitting or having quit. LGBTQ, lesbian, gay, bisexual, two-spirited or queer. EMR, electronic medical record

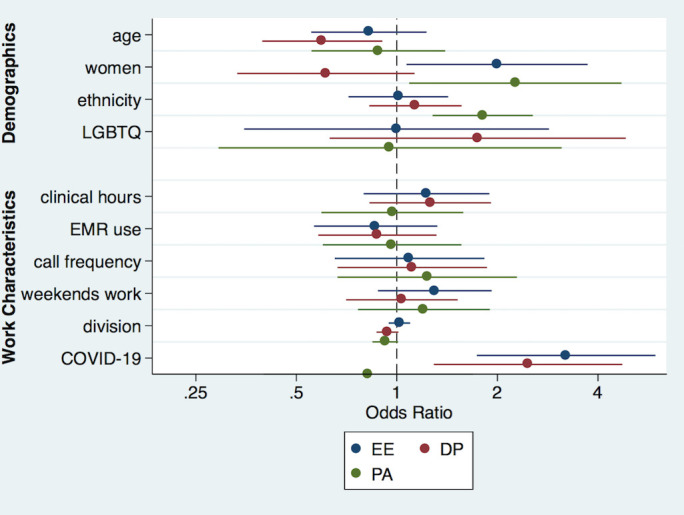

Emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and personal accomplishment

The overall prevalence of emotional exhaustion was 63% (157/250) and depersonalisation was 39% (99/251). Feeling low personal accomplishment was present in 22% (55/249). From figure 3, women were more likely to report emotional exhaustion (adjusted OR (AOR) 2.00, 95% CI: 1.07 to 3.73, p=0.03) and feeling low personal accomplishment (AOR 2.26, 95% CI: 1.09 to 4.70, p=0.03) than men. There was no gender difference for depersonalisation. Visible minority physicians were more likely to report feeling low personal accomplishment compared with white respondents (AOR 1.81, 95% CI: 1.28 to 2.55, p=0.001). Younger respondents were more likely to report depersonalisation than older physicians (AOR 0.60, 95% CI: 0.40 to 0.90, p=0.015). There was no association between ethnicity, sexual orientation, or interaction terms of gender and ethnicity or of gender and sexual orientation, with emotional exhaustion or depersonalisation. There was no association between sexual orientation or the interaction terms of gender and ethnicity or gender and sexual orientation and feelings of low personal accomplishment.

Figure 3.

Multivariate association of burnout subscales, high emotional exhaustion, high depersonalisation and low personal accomplishment. LGBTQ, lesbian, gay, bisexual, two-spirited or queer. EMR, electronic medical record

Having quit or consideration of quitting, and work-to life conflict

Twenty one per cent of respondents reported that they quit a position or are considering quitting a work position (12% (30/257) quit a position and 9% (22/257) were considering quitting). There were no associations between age, gender, ethnicity, or sexual orientation or work characteristics and considering quitting or having quit (figure 2). Forty-one per cent (105/255) of respondents reported work-to-life conflict, not having enough time for personal or family life because of work. There were no associations between gender, ethnicity, or sexual orientation and reporting work-to-life conflict. However, increased clinical hours and working more weekend days were associated with a greater likelihood of reporting work-to-life conflict.

Perceptions about COVID-19 affecting burnout

Physicians who reported that COVID-19 affected their burnout were also more likely to report overall burnout (AOR 3.74, 95% CI: 1.99 to 7.01, p<0.001), emotional exhaustion (AOR 3.21, 95% CI: 1.73 to 5.95, p<0.001) and depersonalisation (AOR 2.47, 95% CI:1.29 to 4.73, p=0.006), but not feelings of low personal accomplishment. Similarly, those who reported that COVID-19 affected burnout were more likely to have quit or considering quitting a work position (AOR: 3.20, 95% CI: 1.34 to 7.66, p=0.009).

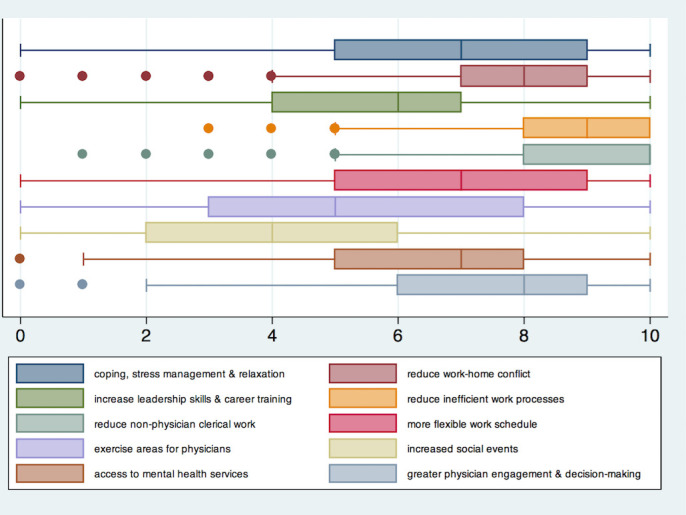

Views on potential interventions to mitigate burnout and promote wellness

Respondents rated interventions focusing on improving organisational factors to reduce burnout and promote wellness as of high importance (figure 4). Ratings of importance did not significantly differ by gender, ethnicity or sexual orientation for each intervention. The interventions with the highest importance ratings were reducing inefficient work processes and non-physician clerical work. The interventions with the lowest importance ratings were increasing social events, leadership skills and career training.

Figure 4.

Ratings on strategies to reduce burnout and promote well-being.

Discussion

During the COVID-19 pandemic, although most of our respondents feel a sense of personal accomplishment, burnout and emotional exhaustion are high. Physicians who endorse that COVID-19 affects their feelings of burnout are more likely to report burnout and to consider quitting a work position or have quit a position. Women and visible minority physicians are more likely to report components of burnout compared with their white counterparts during the pandemic.

The prevalence of burnout and its components in the current study are generally higher than those reported prior to the pandemic. A systematic review of 176 studies from 2018 reported a prevalence of overall burnout of 48.7%, emotional exhaustion of 36.7% and depersonalisation of 32.1% among studies using similar burnout measures.12 Also, a recent meta-analysis of 22, 778 medical and surgical residents identified a 51% aggregate prevalence prior to the pandemic.2 However, given significant heterogeneity in the physician subjects sampled, location and study dates, it is challenging to directly compare prevalence before and after the pandemic. Recent studies from China, Italy and the USA report similarly high rates of burnout among healthcare workers but most do not use standardised, benchmarked burnout questionnaires or examine personal accomplishment.19–22 Our analysis highlights that physicians perceived that COVID-19 increased their burnout. However, burnout was high across all divisions studied regardless of whether they were responsible for caring for patients with COVID-19 or not. This suggests a widespread impact of the pandemic and the restrictions imposed including anxiety related to supply of personal protective equipment, uncertainty and significant shift in clinical practice to virtual care.23 In a recent analysis of surgeons, knowing a person who died from COVID-19 infection or someone who acquired a COVID-19 infection increased the risk of depression, anxiety, stress and post-traumatic stress disorder, irrespective of being deployed for COVID-related work.24 Increased work hours, concerns over infecting family members, lack of support from peers, limited resources and overwork were identified as drivers of burnout and emotional exhaustion during the pandemic.21 22

Given recent social movements focused on racial inequity and the amplification the effects of social disparities during the pandemic,25 our finding that more women experience emotional exhaustion and both women and visible minority physicians are more likely to report feeling low personal accomplishment than their counterparts is important. Although inconsistent, studies of physicians before the pandemic reported a higher risk of emotional exhaustion in women than men.26 27 There are few studies examining gender or ethnicity on burnout during the pandemic. However, a recent analysis of medical trainees demonstrated that women were more likely to report stress compared with men.20 The reasons underlying the high prevalence of emotional exhaustion in women during the pandemic may include more family stress, greater child-raising responsibility than men, increased risk of depression28 and less supportive work environments.6 26 27 Working parents spent an additional 6 hours caring for their children and women took more than two-thirds of that additional time during the pandemic in Canada and elsewhere.29 However, we did not find any gender differences in our one item question on work-to-life conflict. Further, the increased hours spent are thought to be at the expense of academic productivity in women30 and may contribute to feeling low personal accomplishment compared with men. The literature is also inconsistent regarding the impact of race on burnout or its components.7 31 32 A previous national US survey found that minority physicians were less likely to report burnout including emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation compared with white, non-Hispanic physicians,33 whereas others demonstrated no difference in burnout. However, with increased COVID-19 infections, incidents of racial discrimination increased dramatically and this ‘double pandemic’31 may place greater strain on visible minority physicians. Although our study also found no difference in emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation by ethnicity, we identified a greater likelihood of feeling low personal accomplishment. The reasons underlying a feeling of low personal accomplishment in these groups are unknown but may be related to higher prevalence of imposter syndrome, a syndrome where an individual doubts their skills, or accomplishments, increased discrimination or being less likely recognised for their accomplishments than their counterparts.7 30 32 33 Although our study did not find any differences in burnout among sexual minority groups, a previous analysis of medical students found greater rates of depression than heterosexual medical students.8

Given the high prevalence of burnout, strategies to reduce burnout are needed urgently. Most interventions studied thus far include person level interventions to improve resilience and coping with effective tools such as online cognitive behavioural therapy.34 There are fewer studies evaluating additional components that address system-level issues including optimising work quality or quantity. Further, there are few studies evaluating physician preferences for person level, work quality or quantity interventions. In this study, ratings for the interventions that reduced work inefficiencies and non-physician clerical work were rated similarly highly among gender, ethnicity or sexual orientation subgroups. This extends the findings from other observational studies that satisfaction with workflow, relationship with colleagues, time and resources for continuing medical education, opportunity to affect decision making, workload and having a trusted advisor were associated with lower likelihood of burnout.15 These interventions that addressed work quality were highly rated, whereas person-level interventions were less highly rated. New interventions should focus on combining person-level interventions, with system-level approaches that address work quantity and quality interventions.

This study systematically examined burnout using standard measures of burnout during the pandemic. However, there are several limitations to note. First, response rates were somewhat low which increases the risk of non-response bias. However, response rates were comparable to other physician surveys35 36 despite the significant increase in workload during the pandemic and burnout prevalence was nevertheless elevated in divisions that had high response rates. Second, the number of physicians who identified as LGBTQ or non-binary gender was low that may have underestimated any differences. Third, we were not able to quantify any incremental effect of the pandemic on burnout, as we did not have comparable data just prior to the pandemic. Perceptions of COVID-19 impacting feelings of burnout may be subject to confirmation bias. Finally, we sampled physicians from the department of medicine and these results may not necessarily extend to other physician groups such as emergency, primary care, or surgical specialties or allied healthcare workers.

Conclusion

Burnout during the pandemic is affecting two out of every three physicians in this sample. Emotional exhaustion and feeling low personal accomplishment are more prevalent in certain groups including women or visible minority physicians. Interventions reducing inefficient work practices and non-physician work is urgently needed and considered of highly important by all groups. Interventions for improving feelings of personal accomplishment that target gender and ethnic disparities among physicians must also be considered.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Collaborators: On behalf of the Equity Committee at the Department of Medicine, University of British Columbia.

Contributors: NK, AP, PD, DL, HL, SR and AS contributed to the design of the study. NK, AP, AT and DL contributed to data collection and NK contributed towards analysis. All authors contributed to interpretation of the results, and meaningful contribution to writing and accepting the final manuscript. NK had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: This project was unfunded. DL is supported by the Mary Pack Arthritis Chair in Rheumatology Research from the University of British Columbia and the Arthritis Society of Canada.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Please contact the corresponding author for access to data or STATA codes used. nakhanubc@gmail.com, 520B, 1081 Burrard Street St. Paul’s Hospita, Vancouver, British Columbia, BCV6Z IY6.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Providence Health Research Ethics boards H018-02999.

References

- 1.Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general us working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc 2015;90:1600–13. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Low ZX, Yeo KA, Sharma VK, et al. Prevalence of burnout in medical and surgical residents: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:1479. 10.3390/ijerph16091479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharifi M, Asadi-Pooya AA, Mousavi-Roknabadi RS. Burnout among healthcare providers of COVID-19; a systematic review of epidemiology and recommendations. Arch Acad Emerg Med 2021;9:e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tawfik DS, Profit J, Morgenthaler TI, et al. Physician burnout, well-being, and work unit safety grades in relationship to reported medical errors. Mayo Clin Proc 2018;93:1571–80. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dewa CS, Jacobs P, Thanh NX, et al. An estimate of the cost of burnout on early retirement and reduction in clinical hours of practicing physicians in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:254. 10.1186/1472-6963-14-254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linzer M, Harwood E. Gendered expectations: do they contribute to high burnout among female physicians? J Gen Intern Med 2018;33:963–5. 10.1007/s11606-018-4330-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia LC, Shanafelt TD, West CP, et al. Burnout, depression, career satisfaction, and work-life integration by physician Race/Ethnicity. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2012762. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Przedworski JM, Dovidio JF, Hardeman RR, et al. A comparison of the mental health and well-being of sexual minority and heterosexual first-year medical students: a report from the medical student change study. Acad Med 2015;90:652–9. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Public Health Agency of Canada . From risk to resilience: an equity approach to COVID-19. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/from-risk-resilience-equity-approach-covid-19.html#a2 [Accessed 1 Feb 2021].

- 10.American Medical Association . COVID-19 FAQs: health equity in a pandemic. Available: https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/health-equity/covid-19-faqs-health-equity-pandemic [Accessed 1 Feb 2021].

- 11.Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behaviour, 2 (1981), pp. 99-113. Copyright ©1981, 2016 by Christina Maslach & Susan E. Jackson. All rights reserved in all media. Published by Mind Garden, Inc. Available: www.mindgarden.com

- 12.Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, et al. Prevalence of burnout among physicians: a systematic review. JAMA 2018;320:1131–50. 10.1001/jama.2018.12777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:1317-1331. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 14.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:527–33. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2016;388:2272–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clough BA, March S, Chan RJ, et al. Psychosocial interventions for managing occupational stress and burnout among medical doctors: a systematic review. Syst Rev 2017;6:144. 10.1186/s13643-017-0526-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Busireddy KR, Miller JA, Ellison K, et al. Efficacy of interventions to reduce resident physician burnout: a systematic review. J Grad Med Educ 2017;9:294–301. 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00372.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dillman DA. Mail and telephone surveys: the total design method. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amanullah S, Ramesh Shankar R. The impact of COVID-19 on physician burnout globally: a review. Healthcare 2020;8:421. 10.3390/healthcare8040421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sasangohar F, Jones SL, Masud FN, et al. Provider burnout and fatigue during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned from a high-volume intensive care unit. Anesth Analg 2020;131:106–11. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu Y, Wang J, Luo C, et al. A comparison of burnout frequency among oncology physicians and nurses working on the frontline and usual wards during the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;60:e60–5. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Monte C, Monaco S, Mariani R, et al. From resilience to burnout: psychological features of Italian general practitioners during COVID-19 emergency. Front Psychol 2020;11:567201. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.567201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kannampallil TG, Goss CW, Evanoff BA, et al. Exposure to COVID-19 patients increases physician trainee stress and burnout. PLoS One 2020;15:e0237301. 10.1371/journal.pone.0237301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan YQ, Wang Z, Yap QV, et al. Psychological health of surgeons in a time of COVID-19. Ann Surg 2021 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Devakumar D, Shannon G, Bhopal SS, et al. Racism and discrimination in COVID-19 responses. Lancet 2020;395:1194. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30792-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elmore LC, Jeffe DB, Jin L, et al. National survey of burnout among US general surgery residents. J Am Coll Surg 2016;223:440–51. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linzer M, Smith CD, Hingle S, et al. Evaluation of work satisfaction, stress, and burnout among US internal medicine physicians and trainees. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2018758. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.18758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim GY, Tam WW, Lu Y, et al. Prevalence of depression in the community from 30 countries between 1994 and 2014. Sci Rep 2018;8:2861. 10.1038/s41598-018-21243-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnston RM, Mohammed A, van der Linden C. Evidence of exacerbated gender inequality in child care obligations in Canada and Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pol & Gen 2020;16:1131–41. 10.1017/S1743923X20000574 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brubaker L. Women physicians and the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA 2020;324:835–6. 10.1001/jama.2020.14797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Addo IY. Double pandemic: racial discrimination amid coronavirus disease 2019. Soc Sci Humanit Open 2020;2:100074. 10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cantor JC, Mouzon DM. Are Hispanic, black, and Asian physicians truly less burned out than white physicians?: individual and institutional considerations. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2013099. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.13099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osseo-Asare A, Balasuriya L, Huot SJ, et al. Minority resident physicians' views on the role of Race/Ethnicity in their training experiences in the workplace. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e182723. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ho CS, Chee CY, Ho RC, CS H, RC H. Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of COVID-19 beyond paranoia and panic. Ann Acad Med Singap 2020;49:155–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peterson NB, Friedman RH, Ash AS, et al. Faculty self-reported experience with racial and ethnic discrimination in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:259–65. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.20409.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cunningham CT, Quan H, Hemmelgarn B, et al. Exploring physician specialist response rates to web-based surveys. BMC Med Res Methodol 2015;15:32. 10.1186/s12874-015-0016-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Please contact the corresponding author for access to data or STATA codes used. nakhanubc@gmail.com, 520B, 1081 Burrard Street St. Paul’s Hospita, Vancouver, British Columbia, BCV6Z IY6.