Abstract

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 RNA is excreted in feces of most patients, therefore viral load in wastewater can be used as a surveillance tool to develop an early warning system to help and manage future pandemics.

Methods

We collected wastewater from 24 random locations at Bangkok city center and 26 nearby suburbs from July to December 2020. SARS-CoV-2 RNA copy numbers were measured using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Results

SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in wastewater from both the city center and suburbs. Except for July, there were no significant differences in copy numbers between the city center and suburbs. Between October and November, a sharp rise in copy number was observed in both places followed by two to three times increase in December, related to SARS-CoV-2 cases reported for same month.

Conclusions

Our study provided the first dataset related to SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in the wastewater of Bangkok. Our results suggest that wastewater could be used as a complementary source for detecting viral RNA and predicting upcoming outbreaks and waves.

Keywords: COVID-19, Wastewater, Asymptomatic transmission, SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA, Wastewater of Bangkok, SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater

The primary mode of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is via respiratory droplets that people produce when they cough, sneeze or exhale (Hu et al., 2021). A significant proportion of patients with SARS-CoV-2 were reported to have diarrhea in addition to respiratory symptoms (Han et al., 2020, 2021). Several reports have shown that RNA of SARS-CoV-2 can be detected in wastewater samples, and shedding of SARS-CoV-2 was routinely monitored in several countries to predict outbreaks during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and as early warning systems (Medema et al., 2020, Peccia et al., 2020, Wu et al., 2020). The virus can be detected within hours in the stool of asymptomatic or symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 patients (D’Amico et al., 2020, Han et al., 2020, Lodder and de Roda Husman, 2020, Wu et al., 2020). Therefore, the circulation of the virus in the population will increase the viral load in the sewer systems, and give a sneak peek view of both asymptomatic and symptomatic circulation of SARS-CoV-2 (Lodder and de Roda Husman, 2020). Hence, wastewater surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 RNA could be a tool to monitor the circulation of SARS-CoV-2 in communities, estimating the asymptomatic and symptomatic transmission and predicting upcoming waves (Lodder and de Roda Husman, 2020). This method could support current clinical surveillance, which is underreporting the actual number of people infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Thailand was the first country after China to report a case of SARS-CoV-2 and so far is among the handful of countries that avoided the worst outbreaks, with a relatively low number of cases compared to other countries (Dechsupa et al., 2020). However, the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater in Thailand and its relation to the outbreaks have not been investigated. Wastewater was collected twice a month (first week and last week) from 24 random locations at Bangkok city center and 26 nearby suburbs between July and December 2020, and the copy number of SARS-CoV-2 was quantified by real-time PCR technique (Details are available in the Supporting information). The number of SARS-CoV-2 cases for each month was obtained from the Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand (https://covid19.ddc.moph.go.th/en).

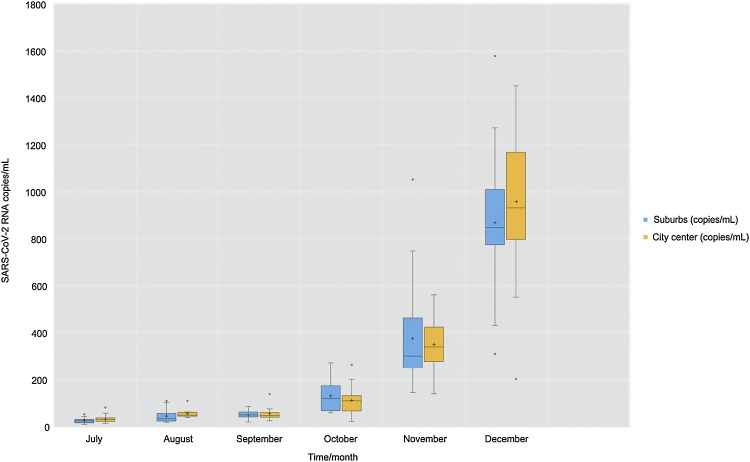

SARS-CoV-2 RNA was present in the wastewater collected from both the city center and suburbs with increasing concentrations from October to December (Figure 1 ). Except for July, August and December there were no statistically significant differences in RNA copy numbers from the city center or suburbs (Table 1 ), probably due to the population dynamics between suburbs and city center. October to November displayed a sharp increase in copy number in both places, followed by a two to three-fold increase in December (Figure 1). The number of confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases remained relatively low from July to November (Table 1) (Supporting information Table S5). Interestingly, in December, the number of SARS-CoV-2 RNA copies from the city center and suburbs in wastewater increased, reflecting the increased number of positive SARS-CoV-2 patients (Table 1) (Supporting information Table S5). This result suggests that a higher copy number of the viral genome could correlate with an elevation in infected people in the community and positive cases may be much higher than the reported numbers.

Figure 1.

Viral loads of SARS-CoV-2 RNA copies in wastewater at each individual location of city center (n = 24) and suburbs (n = 26) from June to December. Each data point indicates the mean copy number of SARS-CoV-2 RNA of each individual location per month. The lower and upper boundaries of the box (interquartile) represent the 25th and the 75th percentile, respectively. The line within the box corresponds to the median and the cross to the mean of the distribution, while the whiskers indicate the highest and the lowest SARS-CoV-2 RNA copy values, except for the outliers that are represented by the rounds outside the whiskers.

Table 1.

Mean viral loads of SARS-CoV-2 RNA copies per month in city center (n = 24) and suburbs (n = 26) with total number of Covid 19 reported cases.

| Months | Suburbs (n = 26) (SARS-CoV-2 RNA copies/mL) with 95% CIa | City center (n = 24) (SARS-CoV-2 RNA copies/mL) with 95% CIa | P (two-tail) between suburbs and city center | Cumulative cases for suburbs (total SARS-CoV-2 cases for each month)c | Cumulative cases for city center (total SARS-CoV-2 cases for each month)d | Cumulative cases national (total SARS-CoV-2 cases for each month)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| July | 24.345 (20.872, 27.817) | 31.345 (26.351, 36.338) | 0.03** | 0 | 0 | 139 |

| August | 28.407 (21.101, 35.714) | 35.222 (27.897, 42.547) | 0.07* | 0 | 0 | 102 |

| September | 50.818 (45.013, 56.624) | 52.682 (41.554, 63.810) | 0.81 | 0 | 0 | 152 |

| October | 129.857 (107.286, 152.428) | 114.429 (94.491, 134.366) | 0.32 | 0 | 0 | 216 |

| November | 385.167 (310.957, 459.377) | 360.000 (314.801, 405.199) | 0.32 | 0 | 0 | 218 |

| December | 877.296 (789.302, 965.291) | 967.926 (871.080, 1064.772) | 0.08* | 1681 | 179 | 2692 |

Mean copy number of SARS-CoV-2 RNA at suburban and city center locations.

Total confirmed coronavirus cases in Thailand obtained from Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand. https://covid19.ddc.moph.go.th/en.

Total confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases in Bangkok city center (Bangkok Metropolis) (The numbers include only locally confirmed cases, and exclude state quarantine for people arriving from overseas).

Total confirmed SARS-CoV-2 RNA cases in nearby suburbs (Nonthaburi, Samut Prakan, Pathum Thani, Samut Sakhon and Nakhon Pathom) obtain form Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand. https://covid19.ddc.moph.go.th/en (The numbers include only locally confirmed case, exclude state quarantine for people arriving from overseas).

P < 0.1.

P < 0.05.

This report is the first study that quantifies SARS-CoV2 in wastewater at Bangkok city center and nearby suburbs. The levels of wastewater SARS-CoV-2 found in this study showed a similar pattern to previous reports in other countries (Medema et al., 2020, Peccia et al., 2020, Wu et al., 2020). The increasing number of SARS-CoV-2 copies in October and November before the second outbreak in December might be due to the asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic transmissions contributing to the forthcoming wave (Medema et al., 2020, Wu et al., 2020). Some studies show that the presence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies among Thai medical personnel and the general population may be higher than what has been officially reported (Nopsopon et al., 2021). These high copy numbers may be related to asymptomatic cases and highlight the potential benefits of using wastewater surveillance as an early warning system (Gonçalves et al., 2021). However, it is not clear how long viral genomes last in wastewater. Daily or weekly sampling and monitoring may give a better perspective on the importance of SARS-CoV-2 surveillance in the wastewater system (Bivins et al., 2020).

Also, a lack of a standard and simple way to correlate virions in wastewater to the number of infected people makes it challenging to interpret the results (Lodder and de Roda Husman, 2020). In addition, there is limited information on the intensity and duration of shedding of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in feces over the course of infection. In our study, the number of SARS-CoV-2 copies in wastewater from the city center and suburbs did not vary significantly, which may be due to the daily commute of people between the city center and suburbs. However, Bangkok is the location of 15.3% of the country’s population (Dechsupa et al., 2020), and therefore, our study numbers based on wastewater sampling twice a month may not give a clear view of the overall picture of Bangkok or Thailand.

Our study implies that detecting SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater systems is a complementary approach to testing people to predict the upcoming outbreaks. Therefore, frequent monitoring of the SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater may significantly impact efforts to understand the disease transmission dynamics.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was not required for this type of environmental waste water surveillance study.

Funding sources

Dhammika Leshan Wannigama was supported by Chulalongkorn University (Second Century Fund — C2F Postdoctoral Fellowship), and the University of Western Australia (Overseas Research Experience Fellowship).

Conflicts of interest

No author declares any potential conflict of interest or competing financial or non-financial interest in relation to the manuscript.

Author contributions

Dhammika Leshan Wannigama: conception, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, writing the original draft of the manuscript.

Mohan Amarasiri: conception, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, writing the original draft of the manuscript.

Cameron Hurst: conception, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, critical review and editing of the manuscript.

Phatthranit Phattharapornjaroen: conception, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, critical review and editing of the manuscript.

Shuichi Abe: conception, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, critical review and editing of the manuscript.

S.M. Ali Hosseini Rad: conception, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, critical review and editing of the manuscript.

Parichart Hongsing: conception, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, critical review and editing of the manuscript.

Lachlan Pearson: conception, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, critical review and editing of the manuscript.

Thammakorn Saethang: data curation, formal analysis, methodology, validation, critical review and editing of the manuscript.

Sirirat Luk-in: data acquisition and curation.

Naris Kueakulpattana: data acquisition and curation.

Robin James Storer: conception, formal analysis, supervision, critical review and editing of the manuscript.

Puey Ounjai: conception, formal analysis, supervision, critical review and editing of the manuscript.

Alain Jacquet: conception, formal analysis, supervision, critical review and editing of the manuscript.

Asada Leelahavanichkul: conception, formal analysis, supervision, critical review and editing of the manuscript.

Tanittha Chatsuwan: conception, funding acquisition, supervision, critical review and editing of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Department of Microbiology staff at King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital for providing testing and technical support and all the volunteers who kindly supported with sample collection.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2021.05.005.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Bivins A., Greaves J., Fischer R., Yinda K.C., Ahmed W., Kitajima M. Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in water and wastewater. Environ Sci Technol Lett. 2020;7(12):937–942. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico F., Baumgart D.C., Danese S., Peyrin-Biroulet L. Diarrhea during COVID-19 infection: pathogenesis, epidemiology, prevention, and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(8):1663–1672. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechsupa S., Assawakosri S., Phakham S., Honsawek S. Positive impact of lockdown on COVID-19 outbreak in Thailand. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;36 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves J., Koritnik T., Mioč V., Trkov M., Bolješič M., Berginc N. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in hospital wastewater from a low COVID-19 disease prevalence area. Sci Total Environ. 2021;755 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C., Duan C., Zhang S., Spiegel B., Shi H., Wang W. Digestive symptoms in COVID-19 patients with mild disease severity: clinical presentation, stool viral RNA testing, and outcomes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(6):916–923. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B., Guo H., Zhou P., Shi Z.-L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19(3):141–154. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00459-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodder W., de Roda Husman A.M. SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater: potential health risk, but also data source. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(6):533–534. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30087-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medema G., Heijnen L., Elsinga G., Italiaander R., Brouwer A. Presence of SARS-Coronavirus-2 RNA in sewage and correlation with reported COVID-19 prevalence in the early stage of the epidemic in The Netherlands. Environ Sci Technol Lett. 2020;7:511–516. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00357. acs.estlett.0c00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nopsopon T., Pongpirul K., Chotirosniramit K., Jakaew W., Kaewwijit C., Kanchana S. Seroprevalence of hospital staff in a province with zero COVID-19 cases. PLoS One. 2021;16(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peccia J., Zulli A., Brackney D.E., Grubaugh N.D., Kaplan E.H., Casanovas-Massana A. Measurement of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater tracks community infection dynamics. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38(10):1164–1167. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0684-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Zhang J., Xiao A., Gu X., Lee W.L., Armas F. SARS-CoV-2 titers in wastewater are higher than expected from clinically confirmed cases. mSystems. 2020;5(4) doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00614-20. e00614–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.