Abstract

Background & Aims

Proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use has been associated with increased risk of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and severe outcomes. However, meta-analyses show unclear results, leading to uncertainty regarding the safety of PPI use during the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Methods

We conducted a nationwide observational study including all SARS-CoV-2 cases (n = 83,224) in Denmark as of December 1, 2020. The association of current PPI use with risk of infection was examined in a case-control design. We investigated the risk of severe outcomes, including mechanical ventilation, intensive care unit admission, or death, in current PPI users (n = 4473) compared with never users. Propensity score matching was applied to control for confounding. Finally, we performed an updated meta-analysis on risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 mortality attributable to PPI use.

Results

Current PPI use was associated with increased risk of infection; adjusted odds ratio, 1.08 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.03–1.13). Among SARS-CoV-2 cases, PPI use was associated with increased risk of hospital admission; adjusted relative risk, 1.13 (1.03–1.24), but not with other severe outcomes. The updated meta-analysis showed no association between PPI use and risk of infection or mortality; pooled odds ratio, 1.00 (95% CI, 0.75–1.32) and relative risk, 1.33 (95% CI, 0.71–2.48).

Conclusions

Current PPI use may be associated with an increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and hospital admission, but these results with minimally elevated estimates are most likely subject to residual confounding. No association was found for severe outcomes. The results from the meta-analysis indicated no impact of current PPI use on COVID-19 outcomes.

Keywords: PPI, COVID-19, Risk of Infection, Mortality

Abbreviations used in this paper: CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ICU, intensive care unit; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; OR, odds ratio; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; RR, relative risk; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SMD, standardized mean difference

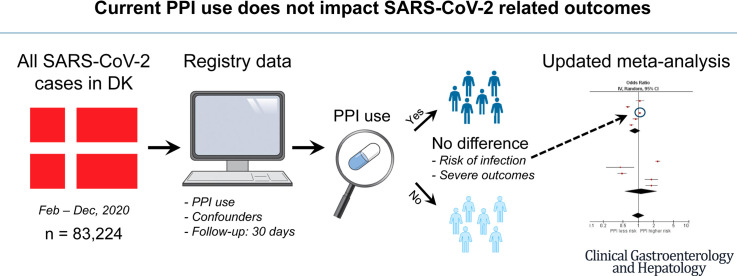

Graphical abstract

What You Need to Know.

Background

To date, uncertainty prevails regarding the safety of proton pump inhibitor use in relation to SARS-CoV-2 infection because existing evidence has indicated both protective and harmful effects.

Findings

In this nationwide observational study, we found a slightly increased risk of infection and hospital admission in 4473 current proton pump inhibitor users but no association with other severe outcomes. Our updated meta-analysis showed no association with risk of infection or mortality.

Implications for patient care

Our findings show that current proton pump inhibitor use does not have a significant clinical impact on risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection or related severe outcomes. Therefore, they suggest that previous conflicting results rather arise from between-study differences.

Acid suppressive drugs, especially proton pump inhibitors (PPI), are hypothesized to influence the susceptibility to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and affect outcomes in patients diagnosed with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). This concern is based on their suppression of stomach acid and an association with an increased risk of infection and, in particular, with a risk of pneumonia.1, 2, 3 SARS-CoV-1 has been reported to be inactivated by acidic conditions,4 and SARS-CoV-2 may directly invade the gastrointestinal epithelium of infected patients.5

In July 2020, a large survey found that individuals using PPI had higher odds of reporting a positive SARS-CoV-2 test.6 In contrast, Lee et al7 reported that current PPI use was associated with an increased risk of severe outcomes of COVID-19 but not with risk of infection. Similarly, Zhou et al8 reported an association with severe outcomes, including need for intensive care unit (ICU) admission, intubation, or death.

Subsequently, 2 meta-analyses9 , 10 including 14 further observational studies of PPI use in patients with COVID-19 found that PPI use was associated with an increased risk of severe outcomes. However, most of the studies had low statistical precision of estimates, only some controlled fully for confounding, and they were all quite heterogenous, with study populations from different countries, including patients with few or many comorbidities and with or without requiring hospitalization. Currently, use of PPI and its possible association with risk of infection and disease severity remain uncertain.

In this nationwide study of all individuals tested in Denmark as of December 1, 2020, we examined the association between current use of PPI and risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the risk of hospital admission, ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, or death among individuals with current PPI use and a positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA test. In addition, we performed an updated meta-analysis of studies reporting risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 mortality in current PPI users.

Methods

Study Register

The original study protocol and analysis plan are available from the EU PAS Register with identification number EUPAS35835: http://www.encepp.eu/encepp/viewResource.htm?id=37050.

Data Source

Data on all Danish residents tested for SARS-CoV-2 RNA as of December 1, 2020 were retrieved from the Danish Microbiology Database and individually linked to other nationwide health care registries, as described previously.11

SARS-CoV-2 infection was verified by a positive real-time polymerase chain reaction on an oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal swab or lower respiratory tract specimen. The individuals’ medical history included International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision diagnoses registered within 10 years before the date of first positive SARS-CoV-2 test (index date). Comorbidities included were peptic ulcer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, ischemic heart disease, stroke, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, renal failure, and cirrhosis. Lifestyle factors included smoking- and alcohol-related diagnoses (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Individuals With and Without Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection (Case-Control Study)

| Cases (n = 83,224) | Controls (n = 332,799) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 36 (21–53) | 36 (21–53) | .85 |

| Sex (male), N (%) | 41,501 (49.9) | 165,946 (49.9) | .99 |

| Exposure to proton pump inhibitors, N (%) | |||

| Non-use | 59,413 (71.4) | 241,536 (72.6) | <.001 |

| Current use | 4473 (5.4) | 17,553 (5.3) | .25 |

| Former use | 19,338 (23.2) | 73,710 (22.1) | <.001 |

| No. of prior admissions, N (%)a | |||

| 0 | 66,144 (79.5) | 267,533 (80.4) | <.001 |

| 1 | 10,497 (12.6) | 40,240 (12.1) | <.001 |

| 2 | 3235 (3.9) | 12,234 (3.7) | .004 |

| 3+ | 3348 (4.0) | 12,792 (3.8) | .02 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, N (%) | |||

| 0 | 74,797 (89.9) | 299,207 (89.9) | .79 |

| 1–2 | 7099 (8.5) | 28,225 (8.5) | .65 |

| 3+ | 1328 (1.6) | 5367 (1.6) | .73 |

| Diagnoses, N (%)b | |||

| Peptic ulcer | 400 (0.5) | 1639 (0.5) | .68 |

| Asthma | 2574 (3.1) | 9726 (2.9) | .010 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 957 (1.1) | 4775 (1.4) | <.001 |

| Cirrhosis | 71 (0.1) | 445 (0.1) | <.001 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 4020 (4.8) | 15,537 (4.7) | .05 |

| Diabetes | 2452 (2.9) | 8308 (2.5) | <.001 |

| Renal failure | 769 (0.9) | 2905 (0.9) | .16 |

| Heart failure | 773 (0.9) | 2943 (0.9) | .22 |

| Stroke | 1241 (1.5) | 5272 (1.6) | .05 |

| Alcohol-related diagnoses | 785 (0.9) | 5156 (1.5) | <.001 |

| Smoking-related diagnoses | 581 (0.7) | 3801 (1.1) | <.001 |

| Major psychiatric disorders | 305 (0.4) | 1977 (0.6) | <.001 |

| Medication, N (%)c | |||

| Systemic corticosteroids | 738 (0.9) | 3428 (1.0) | <.001 |

| Inhaled corticosteroids | 2674 (3.2) | 11,086 (3.3) | .09 |

| Bronchodilators | 1657 (2.0) | 7638 (2.3) | <.001 |

| H2-receptor antagonists | — | — | <.001 |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 3650 (4.4) | 14,984 (4.5) | .15 |

| Anticholinergic agents | 325 (0.4) | 1631 (0.5) | <.001 |

| Immunosuppressants | 210 (0.3) | 936 (0.3) | .16 |

| Antipsychotic agents | 859 (1.0) | 4919 (1.5) | <.001 |

| Antibiotics | 6546 (7.9) | 24,494 (7.4) | <.001 |

| Alcohol abstinence treatment | 62 (0.1) | 480 (0.1) | <.001 |

| Smoking cessation treatment | 70 (0.1) | 528 (0.2) | <.001 |

| Blood pressure lowering drugs | 8353 (10.0) | 35,053 (10.5) | <.001 |

| Lipid lowering drugs | 5011 (6.0) | 19,929 (6.0) | .72 |

| Glucose lowering drugs | 3090 (3.7) | 10,356 (3.1) | <.001 |

| Antiplatelets | 2447 (2.9) | 10,450 (3.1) | .003 |

| Anticoagulants | 1526 (1.8) | 6163 (1.9) | .74 |

IQR, interquartile range.

During the past 3 years.

Diagnoses within 10 years before inclusion.

Use within 90 days before inclusion.

Major psychiatric disorders (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorders, manic episodes, and bipolar disorder) were added along with available frailty markers based on health care utilization (number of admissions within the past 3 years).

Data on patients’ medications included current use (within 90 days before index date) of inhaled corticosteroids and bronchodilators, systemic corticosteroid treatment, immunomodulating treatment, H2-receptor antagonists, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), anticholinergic agents, antibiotics, blood pressure lowering drugs, lipid lowering drugs, glucose lowering drugs, antiplatelets, anticoagulants, treatment to support alcohol abstinence and smoking cessation, and antipsychotic agents (Supplementary Table 1). Finally, the total burden of comorbidity was assessed on the basis of the Charlson Comorbidity Index and classified as 0, 1–2, or ≥3.

Study Design and Population

The case-control study included all individuals tested for SARS-CoV-2 RNA and examined the risk of infection with current PPI use in cases (test-positive) vs controls (test-negative). Cases were matched on sex and birth year with up to 4 controls each. Control subjects were Danish residents alive at the index date of the case and who had been tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 RNA. To account for changing testing criteria and in-hospital capacity during the study period, cases were matched with controls on the week wherein the test was performed.

The cohort study included the test-positive population and investigated the risk of hospital admission and severe outcomes, including ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and death, within 30 days of the first positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA test. Patients were followed from date of first positive test until death, migration, or end of follow-up (30 days).

Exposure

Current PPI use was defined as having redeemed a prescription of PPI within 90 days before the first positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA test (index date), although only including prescriptions before possible hospitalization. Individuals were classified as former users if they had redeemed a prescription more than 90 days before the index date. Never use was defined as never having redeemed a prescription since 2005. The specific PPI (pantoprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole, or esomeprazole) was registered for each user. Dose levels were defined as low or high dose if the prescribed tablet strength was either below or equal to/above 30 mg, respectively. The choice of dose level cutoff was based on usual tablet sizes and a standard once-daily dosing regimen.

Outcomes

In the case-control study, the outcome was a positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA test during the study period.

In the cohort study, the primary outcome was hospital admission within 30 days after a positive test for SARS-CoV-2 RNA or a positive test for SARS-CoV-2 RNA within 48 hours of hospital admission if hospitalized before the date of testing. Secondary outcomes included ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and death within 30 days of a positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA test. Finally, a composite of severe outcomes, including ICU admission or death, was added as a post hoc analysis to compare with recent studies.

Meta-analysis

To put our study results in context with other studies, we performed a literature search in the global search engine maintained by World Health Organization, WHO COVID-19 database, https://search.bvsalud.org/global-literature-on-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov/. Li et al10 recently reported a comprehensive meta-analysis of PPI use and clinical outcomes including 16 studies. Therefore, we applied the same search strategy for the remaining period (September 23–December 14) (Supplementary Table 2). Studies examining the impact of current PPI use compared with never use on risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection or COVID-19 mortality were included. However, in contrast to Li et al, we did not include the composite outcome of ICU admission or mortality because we find it difficult to interpret the clinical meaning of this result.

Two authors (AL, TB) independently extracted outcome data from study publications and assessed studies for risk of bias. High risk of bias was defined as studies not dealing with confounding at either study design level or in the included analyses or if studies had other important biases, eg, high risk of selection bias.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables are presented as median with interquartile range, whereas categorical variables are presented as count with percentage. Baseline characteristics are reported separately for the case-control and the cohort study populations.

In the case-control study, conditional logistic regression was performed to examine a possible association between current PPI use and risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Results are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Confounding by age, sex, and calendar time were handled by the risk set sampling and the matched analysis, as described above. Other potential confounders, including comorbidity and current medication use, are listed in Table 1 and included in the multivariable modelling. Comparisons between groups were performed using Fisher exact test or t test, as appropriate.

In the cohort study, an individual propensity score of drug exposure was estimated by logistic regression based on age, sex, comorbidities, and current medication use, as listed in Table 2 . Propensity scores were used to match the exposed and unexposed groups to adjust for preexisting differences in risk factors. Covariate balance was quantified by standardized mean differences (SMDs), with values below 0.1 considered acceptable. Relative risks (RRs) for hospital admission and severe outcomes in the exposed (current PPI use) vs the unexposed (never PPI use) groups were calculated by log binomial regression and presented as crude (unmatched) and adjusted (propensity score matched) estimates with 95% CI.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Individuals Infected With Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 According to Current or Never Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors Before and After Propensity Score Matching (Cohort Study)

| Use of proton pump inhibitors |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmatched |

Matched |

|||||

| Current (n = 4473) | Never (n = 59,413) | Standardized mean difference | Current (n = 3955) | Never (n = 3955) | Standardized mean difference | |

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 60 (48–73) | 29 (18–47) | 1.42 | 58 (46–71) | 59 (47–73) | 0.07 |

| Sex (male) | 1989 (44.5) | 31,224 (52.6) | 0.16 | 1770 (44.8) | 1758 (44.5) | 0.01 |

| No. of prior admissions, N (%)a | ||||||

| 0 | 2416 (54.0) | 50,230 (84.5) | 0.70 | 2353 (59.5) | 2568 (64.9) | 0.11 |

| 1 | 781 (17.5) | 6466 (10.9) | 0.19 | 710 (18.0) | 695 (17.6) | 0.01 |

| 2 | 425 (9.5) | 1596 (2.7) | 0.29 | 375 (9.5) | 274 (6.9) | 0.09 |

| 3+ | 851 (19.0) | 1121 (1.9) | 0.58 | 517 (13.1) | 418 (10.6) | 0.08 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, N (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 2980 (66.6) | 55,696 (93.7) | 0.72 | 2846 (72.0) | 2920 (73.8) | 0.04 |

| 1–2 | 1077 (24.1) | 3328 (5.6) | 0.54 | 871 (22.0) | 814 (20.6) | 0.04 |

| 3+ | 416 (9.3) | 389 (0.7) | 0.41 | 238 (6.0) | 221 (5.6) | 0.02 |

| Diagnoses, N (%)b | ||||||

| Peptic ulcer | 147 (3.3) | 16 (0.0) | 0.26 | 22 (0.6) | 16 (0.4) | 0.02 |

| Asthma | 329 (7.4) | 1378 (2.3) | 0.24 | 222 (5.6) | 203 (5.1) | 0.02 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 287 (6.4) | 289 (0.5) | 0.33 | 170 (4.3) | 143 (3.6) | 0.04 |

| Cirrhosis | 31 (0.7) | 10 (0.0) | 0.11 | 12 (0.3) | 9 (0.2) | 0.01 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 623 (13.9) | 699 (1.2) | 0.50 | 404 (10.2) | 393 (9.9) | 0.01 |

| Diabetes | 564 (12.6) | 891 (1.5) | 0.44 | 378 (9.6) | 353 (8.9) | 0.02 |

| Renal failure | 231 (5.2) | 222 (0.4) | 0.30 | 118 (3.0) | 107 (2.7) | 0.02 |

| Heart failure | 209 (4.7) | 247 (0.4) | 0.27 | 134 (3.4) | 125 (3.2) | 0.01 |

| Stroke | 296 (6.6) | 463 (0.8) | 0.31 | 210 (5.3) | 200 (5.1) | 0.01 |

| Alcohol-related diagnoses | 118 (2.6) | 410 (0.7) | 0.15 | 79 (2.0) | 77 (1.9) | 0.00 |

| Smoking-related diagnoses | 85 (1.9) | 218 (0.4) | 0.15 | 57 (1.4) | 58 (1.5) | 0.00 |

| Major psychiatric disorders | 50 (1.1) | 140 (0.2) | 0.11 | 32 (0.8) | 34 (0.9) | 0.01 |

| Medication, N (%)c | ||||||

| Systemic corticosteroids | 235 (5.3) | 237 (0.4) | 0.30 | 147 (3.7) | 120 (3.0) | 0.04 |

| Inhaled corticosteroids | 513 (11.5) | 1276 (2.1) | 0.38 | 354 (9.0) | 333 (8.4) | 0.02 |

| Bronchodilators | 322 (7.2) | 775 (1.3) | 0.30 | 226 (5.7) | 201 (5.1) | 0.03 |

| H2-receptor antagonists | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 691 (15.4) | 1707 (2.9) | 0.45 | 565 (14.3) | 582 (14.7) | 0.01 |

| Anticholinergic agents | 92 (2.1) | 96 (0.2) | 0.18 | 62 (1.6) | 49 (1.2) | 0.03 |

| Immunosuppressants | 36 (0.8) | 94 (0.2) | 0.09 | 30 (0.8) | 24 (0.6) | 0.02 |

| Antipsychotic agents | 195 (4.4) | 357 (0.6) | 0.24 | 137 (3.5) | 134 (3.4) | 0.00 |

| Antibiotics | 971 (21.7) | 3487 (5.9) | 0.47 | 705 (17.8) | 713 (18.0) | 0.01 |

| Alcohol abstinence treatment | 15 (0.3) | 25 (0.0) | 0.07 | 10 (0.3) | 12 (0.3) | 0.01 |

| Smoking cessation treatment | 20 (0.4) | 30 (0.1) | 0.08 | 10 (0.3) | 9 (0.2) | 0.01 |

| Blood pressure lowering drugs | 1737 (38.8) | 3598 (6.1) | 0.85 | 1401 (35.4) | 1438 (36.4) | 0.02 |

| Lipid lowering drugs | 1093 (24.4) | 1987 (3.3) | 0.64 | 875 (22.1) | 903 (22.8) | 0.02 |

| Glucose lowering drugs | 635 (14.2) | 1245 (2.1) | 0.45 | 473 (12.0) | 466 (11.8) | 0.01 |

| Antiplatelets | 597 (13.3) | 902 (1.5) | 0.46 | 446 (11.3) | 442 (11.2) | 0.00 |

| Anticoagulants | 368 (8.2) | 588 (1.0) | 0.35 | 272 (6.9) | 259 (6.5) | 0.01 |

IQR, interquartile range.

During the past 3 years.

Diagnoses within 10 years before inclusion.

Use within 90 days before inclusion.

To determine the robustness of the estimates, sensitivity analyses on the chosen PPI exposure window were performed in both studies and included comparisons of current vs former use and former vs never use. Finally, a post hoc analysis of the dose-effect of PPI was computed comparing low-dose vs high-dose regimens, as defined above.

In the meta-analyses, we preferred adjusted estimates to unadjusted estimates. To include as much information as possible, we extracted estimates for the effect measure most frequently reported in the studies, eg, OR. For studies using a different effect measure, unadjusted results based on reported events were calculated. Inverse variance random-effects models were applied to estimate either OR or RR with 95% CI. We described statistical heterogeneity using I 2 and explored our results in subgroup analysis stratified by risk of bias. Meta-analyses were conducted in RevMan 5.4.1.

Results

Between February 27 and December 1, 2020, 83,224 cases with SARS-CoV-2 infection were identified. Of these, 4473 (5%) were current users of PPI, and 19,338 (23%) were former users. Among current users, pantoprazole accounted for 57% of prescriptions, whereas users of lansoprazole, omeprazole, and esomeprazole numbered 833 (19%), 749 (17%), and 324 (7%), respectively.

Characteristics of Cases and Controls

Cases (n = 83,224) and controls (n = 332,799) had a median age of 36 years and an equal sex distribution. Less than 15% had a score of 1 or more in the Charlson Comorbidity Index (Table 1). The predominant comorbidity was ischemic heart disease, followed by asthma, diabetes, stroke, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Blood pressure lowering drugs were the most common drugs used in both cases and controls. Other common medications used included lipid lowering drugs, glucose lowering drugs, antibiotics and NSAIDs.

Risk of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection

Current PPI users had a crude OR of 1.04 (95% CI, 1.00–1.08) of SARS-CoV-2 infection compared with never PPI users. After including all the covariates in the regression model, the adjusted OR was 1.08 (95% CI, 1.03-1.13). The sensitivity analyses (current vs former use and former vs never use) yielded similar results with crude and adjusted ORs around 1.0 (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Odds of Infection With Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 for Cases Compared With Controls According to Current, Former, or Never Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors

| Proton pump inhibitor use | Crude odds ratio (95% CI) | Adjusteda odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Current versus never | 1.04 (1.00–1.08) | 1.08 (1.03–1.13) |

| Current low dose versus never | 1.01 (0.95–1.07) | 1.04 (0.98–1.11) |

| Current high dose versus never | 1.06 (1.01–1.11) | 1.11 (1.05–1.16) |

| Current versus former | 0.98 (0.93–1.02) | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) |

| Former versus never | 1.08 (1.06–1.10) | 1.08 (1.06–1.10) |

CI, confidence interval.

Adjusted for age, sex, comorbidities, current medication use, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and number of hospital admissions within the last 3 years.

In the dose-response analysis, individuals with current low-dose PPI use had an adjusted OR of 1.04 (95% CI, 0.98–1.11) of SARS-CoV-2 infection, whereas individuals with current high-dose PPI use had an adjusted OR of 1.11 (95% CI, 1.05–1.16) when compared with never PPI use (Table 3). When comparing the different classes of PPI, lansoprazole, omeprazole, and esomeprazole had adjusted ORs below 1.0 compared with pantoprazole, but all estimates had low statistical precision (Supplementary Table 3).

Characteristics of Current and Never Users of Proton Pump Inhibitor Among Patients With Positive Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 RNA

In the unmatched SARS-CoV-2 RNA positive population, current users of PPI (n = 4473) were compared with never users of PPI (n = 59,413). Current users were older (median 60 vs 29 years), fewer were male (45% vs 53%), and they had a greater comorbidity burden with a larger proportion of registered diagnoses across all the included comorbidities (Table 2). Use of other medications was also consistently more frequent in current users compared with never users (Table 2).

After propensity score matching, 3955 individuals persisted in each group, and the difference in characteristics was significantly reduced, with 89% of the SMDs below 0.05 and none with SMD above 0.11 (Table 2). However, important comorbidities and prior health care utilization remained more frequent in current users.

Hospital Admission and Severe Outcomes of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection

In the propensity score matched analyses, current PPI users had an increased risk of hospital admission compared with never PPI users (19% vs 16%), corresponding to an adjusted RR of 1.13 (95% CI, 1.03–1.24) (Table 4 ). Current and never PPI users had comparable risks of ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, death, and severe outcomes (ICU or death) at around 2%, 1%, 4%, and 6%, respectively. The RR for these secondary outcomes in the matched analysis had estimates just below or at 1.0, with 95% CIs on both sides of 1 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Relative Risk of Hospital Admission, Intensive Care Unit Admission, Mechanical Ventilation, or Death for Current and Never Users of Proton Pump Inhibitors

| Outcome | Current proton pump inhibitor use |

Never proton pump inhibitor use |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | Risk (%) | Events | Risk (%) | Relative risk | |

| Crude | |||||

| Hospital admission | 995/4473 | 22.2 (21.0–23.5) | 2145/59,413 | 3.6 (3.5–3.8) | 6.16 (5.75–6.60) |

| ICU admission | 118/4473 | 2.6 (2.2–3.1) | 254/59,413 | 0.4 (0.4–0.5) | 6.17 (4.97–7.66) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 68/4473 | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) | 145/59,413 | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 6.23 (4.68–8.30) |

| Death | 269/4473 | 6.0 (5.3–6.7) | 280/59,413 | 0.5 (0.4–0.5) | 12.76 (10.82–15.04) |

| ICU or death | 353/4473 | 7.9 (7.1–8.7) | 487/59,413 | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 9.63 (8.42–11.00) |

| Matched | |||||

| Hospital admission | 734/3955 | 18.6 (17.3–19.8) | 650/3955 | 16.4 (15.3–17.6) | 1.13 (1.03–1.24) |

| ICU admission | 92/3955 | 2.3 (1.9–2.8) | 95/3955 | 2.4 (1.9–2.9) | 0.97 (0.73–1.29) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 55/3955 | 1.4 (1.0–1.8) | 55/3955 | 1.4 (1.0–1.8) | 1.00 (0.69–1.45) |

| Death | 166/3955 | 4.2 (3.6–4.8) | 189/3955 | 4.8 (4.1–5.4) | 0.88 (0.72–1.08) |

| ICU or death | 235/3955 | 5.9 (5.2–6.7) | 260/3,955 | 6.6 (5.8–7.3) | 0.90 (0.76–1.07) |

ICU, intensive care unit.

The sensitivity analysis comparing current and former users showed risks of 21% and 19% for hospital admission with a similar adjusted RR of 1.08 (95% CI, 1.00-1.18). When comparing former users with never users, the risks of hospital admission were comparable between the groups (Supplementary Table 4).

In the dose-response analysis, the risk of hospital admission for current PPI users with a high-dose regimen was increased with an adjusted RR at 1.19 (95% CI, 1.07-1.32), whereas current users with a low-dose regimen had an adjusted RR of 1.03 (95% CI, 0.90–1.17), when compared with never PPI users. All secondary outcomes were not statistically significant (Supplementary Table 5).

When comparing the different classes of PPI, neither consistent nor statistically significant differences were observed in risk of hospital admission or severe outcomes (Supplementary Table 6).

Meta-analysis of Risk of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection

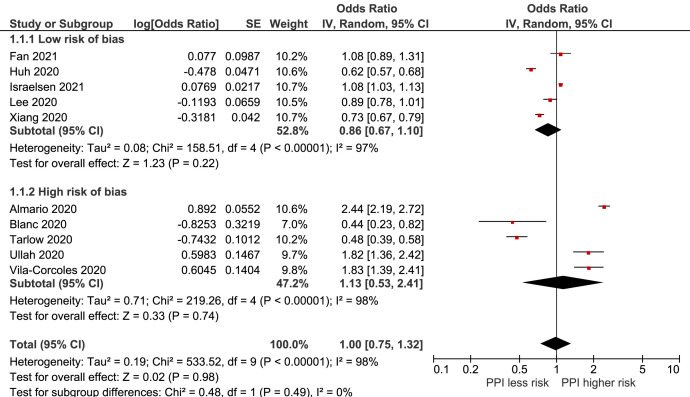

In the updated literature search, 8 studies,6 , 7 , 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 including our current study, investigated the association between current PPI use and risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. In addition, a recent nationwide study was included alongside a relevant preprint not detected in the initial search.17 , 18 Study characteristics are shown in Supplementary Table 7. Analysis of these studies, comprising 730,941 individuals, resulted in a pooled OR of 1.00 (95% CI, 0.75-1.32), with considerable between-study heterogeneity (I 2 = 98%) (Figure 1 ). When divided into subgroups on the basis of risk of bias, the analysis of the 5 studies with high risk of bias showed an OR of 1.13 (95% CI, 0.53–2.41) for current PPI use compared with never use (Figure 1). Furthermore, the 5 studies with low risk of bias showed a decreased risk of infection, although with low statistical precision, OR of 0.86 (95% CI, 0.67–1.10) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Forest plot of the association between proton pump inhibitor use and risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; SE, standard error.

Meta-analysis of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Mortality

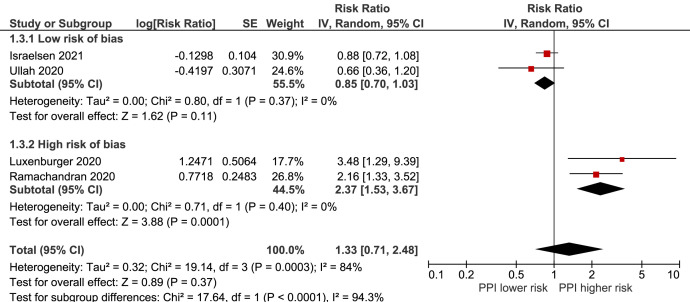

Only 4 studies12 , 19 , 20 reported the association between current PPI use and mortality alone, including 4150 current PPI users (Supplementary Table 7). The overall analysis showed an RR of 1.33 (95% CI, 0.71–2.48) in current PPI users compared with never users, although estimates differed between studies with low risk of bias, RR 0.85 (95% CI, 0.70–1.03), and high risk of bias, RR 2.37 (1.53–3.67) (interaction test: P < .0001) (Figure 2 ). The between-study heterogeneity was substantial (I 2 = 84%).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the association between proton pump inhibitor use and COVID-19 mortality. CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; SE, standard error.

Discussion

Overall, current use of PPI was associated with an increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the case-control study and an increased risk of hospital admission in the cohort study including test-positive individuals. However, both estimates were close to 1.0 and may be caused by residual confounding. Moreover, current use of PPI was not associated with increased risk of severe outcomes that included ICU admission or death.

The lack of a clinically significant association with increased risk of infection in current PPI users in our study is consistent with most previous reports and our updated meta-analysis. In contrast, the meta-analysis by Li et al10 showed that current PPI use was associated with increased odds of infection, although the estimate was statistically uncertain.

Our results show a possible association between current PPI use and increased risk of hospital admission in SARS-CoV-2 RNA positive individuals. However, we could not confirm the association with increased risk of severe outcomes of COVID-19 with current PPI use as reported in previous meta-analyses.9 , 10 , 21 , 22 In addition, a multicenter study from North America and a nationwide United Kingdom study, not included in any of the meta-analyses, did not find an association between PPI use and severe outcomes either.18 , 23

Notably, all the studies reporting the impact of PPI use in SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals differ substantially. First, the study populations are rather heterogenous including different nationalities and ranging from young resourceful individuals6 to elderly with several comorbidities12 , 13 and between hospitalized patients and residents without hospital contact. The SARS-CoV-2 RNA positive population in our study had comorbidities corresponding to previous reports of diagnoses commonly present in infected individuals24 and included both residents without hospital contact and hospitalized patients. Second, the study designs vary from small single center studies19 , 20 to large nationwide cohorts,7 , 18 and study results are presented as only crude estimates14 or after adjustment for possible confounders, some by use of propensity score matched methods.7 , 8 , 18 Third, current use of PPI was defined in different ways and in some studies not reported at all.

The associations with increased risk of infection and hospital admission for current PPI use identified here may have arisen from limitations associated with an observational design. Although a wide range of relevant comorbidity and medication was used to adjust our analyses, there may inherently remain residual confounding by imperfectly measured, unmeasured, or unknown factors. In addition, the propensity score matching failed to fully account for important differences in comorbidities and prior health care use between current and never users. Use of PPI has been associated with socioeconomic deprivation and frailty, but this information was not available through the applied registries. Similarly, information on the indication for use of PPI was unavailable except for a prior diagnosis of peptic ulcer. Interestingly, Luxenburger et al20 found that gastroesophageal reflux disease was independently associated with severe courses of COVID-19, thereby raising the question whether the indication for the drug prescription accounts for the association rather than the drug per se. Furthermore, PPI is linked to overprescribing, which could be another (unknown) marker of frailty.25 Low-dose PPI is available as over-the-counter medicine in Denmark, which could give rise to information bias, affecting the results toward the null.

Finally, for the test-negative case-control study of PPI use as risk factor for contracting SARS-CoV-2-infection, there is a potential bias if PPI affects the chance of becoming a control, ie, being tested negative. In the early stages of the pandemic, most test-negative individuals had other viral upper respiratory infections, which to our knowledge is not associated with PPI use in general.

Our updated meta-analysis showed a possible increased risk of COVID-19 mortality, but no risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, neither of these results were statistically significant. Indeed, when we restricted our analyses to studies with low risk of bias, the point estimates decreased to below 1.0 in both analyses, indicating that the conflicting results from the included studies and former meta-analyses arise from between-study differences rather than an actual impact of current PPI use on COVID-19 outcomes.

In conclusion, our data support that PPI use in general is safe with regard to risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19 outcomes. The risk of hospital admission was increased for current PPI users, but this minimally elevated RR is seemingly explained by residual confounding. Following hospital admission there was no association with severity of COVID-19 and use of PPI. Finally, our updated meta-analysis indicated no impact of current PPI use on COVID-19 outcomes, thereby suggesting that previous conflicting results are more likely due to differences in study design and population.

Acknowledgments

CrediT Authorship Contributions

Simone Bastrup Israelsen, MD (Conceptualization: Equal; Funding acquisition: Equal; Investigation: Equal; Methodology: Equal; Writing – original draft: Lead; Writing – review & editing: Equal)

Martin Thomsen Ernst (Formal analysis: Lead; Investigation: Equal; Methodology: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

Andreas Lundh (Formal analysis: Supporting; Investigation: Equal; Methodology: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal)

Lene Fogt Lundbo (Conceptualization: Equal; Investigation: Equal; Methodology: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal)

Håkon Sandholdt (Formal analysis: Supporting; Investigation: Equal; Methodology: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

Jesper Hallas (Investigation: Equal; Methodology: Equal; Supervision: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Equal)

Thomas Benfield (Conceptualization: Equal; Funding acquisition: Equal; Investigation: Equal; Methodology: Equal; Supervision: Lead; Writing – review & editing: Equal)

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest This author discloses the following: Thomas Benfield reports grants from Novo Nordisk Foundation, grants from Simonsen Foundation, grants and personal fees from GSK, grants and personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants and personal fees from Gilead, personal fees from MSD, grants from Lundbeck Foundation, grants from Kai Hansen Foundation, and personal fees from Pentabase A/S, with no relation to the work reported in this article. The remaining authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding Supported by a grant from Erik and Susanna Olesen’s Charitable Fund. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology at www.cghjournal.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2021.05.011.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1.

Covariates and Corresponding ATC/Diagnoses Codes Included in the Propensity Score Model

| Type of information | Variables | Time frame/diagnosis codes |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Sex | |

| Date of birth | ||

| Health care utilization | No. of hospital admissions | Within 3 years before index date |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0 | Since 1994 (ICD-10) |

| 1–2 | ||

| 3+ | ||

| Comorbidities | Peptic ulcer | K25, K26, K27 |

| Asthma | J45 | |

| COPD | J44 | |

| Cirrhosis | K703, K717A, K717B, K743, K744, K745, K746, K746B, K746C, K746D, K746E, K746F, K746G, K746H, DP788A | |

| Ischemic heart disease | I20, I21, I22, I23, I24, I25, N02BA, C01DA, B01AC24 |

|

| Diabetes mellitus | E10, E11, E13, E14 | |

| Renal failure | I12, I13, N00-N05, N07, N08, N11, N14, N18, N19, E102, E112, E142 | |

| Heart failure | I099A, I110, I130, I132, I50 | |

| Stroke | I60, I61, I62, I63, I64, I69 | |

| Alcohol-related diagnosis or drug use | F10, E244, G312, G621, G721, I426, K292, K70, K852, K860, Q860, Z502, Z714, Z721 | |

| Smoking-related diagnosis | DF17, DZ716, DZ720 | |

| Major psychiatric disorder | F20, F25, F30, F31 | |

| Medication | Systemic corticosteroids | H02AB |

| Inhaled corticosteroids | R03AK, R03AL, R03BA | |

| Bronchodilators | R03AA, R03AC | |

| H2RA | A02BA | |

| NSAID | M01A (excluding M01AX) | |

| Anticholinergic agents | R03BB | |

| Immunosuppressants | L04AA, L04AB, L04AC, L04AD, L04AX, L01XC02 | |

| Antipsychotic agents | N05AA, N05AB, N05AC, N05AD, N05AE, N05AF, N05AG, N05AH, N05AL, N05AN, N05AX | |

| Antibiotics | J01 | |

| Alcohol abstinence treatment | N07BB | |

| Smoking cessation treatment | N07BA | |

| Blood pressure lowering drugs | C03A, C07, C08, C09 | |

| Lipid lowering drugs | C10 | |

| Glucose lowering drugs | A10A, A10B | |

| Antiplatelets | B01AC | |

| Anticoagulants | B01AA, B01AE07, B01AF |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, H2RA, H2-receptor antagonists; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases version 10, NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Supplementary Table 2.

Search Strategy for Meta-analysis

| World Health Organization COVID-19 database September 23–December 14. (tw:(proton pump inhibitor∗)) OR (tw:(ppi∗ )) OR (tw:(h2-receptor antagonist∗)) OR (tw:(hypochlorhydria)) OR (tw:(gastric acid)) OR (tw:(gastric ph)) OR (tw:(omeprazole)) OR (tw:(rabeprazole)) OR (tw:(esomeprazole)) OR (tw:(pantoprazole)) OR (tw:(lansoprazole)) OR (tw:(gastrointestinal)) |

Supplementary Table 3.

Odds of Infection With SARS-Cov-2 for Cases Compared With Controls According to Use of Different Classes of Proton Pump Inhibitors

| Proton pump inhibitor use | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusteda OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Lansoprazole versus pantoprazole | 0.85 (0.70–1.02) | 0.84 (0.69–1.02) |

| Omeprazole versus pantoprazole | 0.85 (0.69–1.04) | 0.83 (0.67–1.03) |

| Esomeprazole versus pantoprazole | 0.84 (0.61–1.15) | 0.82 (0.59–1.14) |

CI, confidence interval; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases version 10; OR, odds ratio; SARS-Cov-2, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2.

Adjusted for age, sex, comorbidities (peptic ulcer, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cirrhosis, ischemic heart disease, diabetes, renal failure, heart failure, stroke, alcohol-related diagnoses, smoking-related diagnoses, major psychiatric disorders), other current medication use (systemic and inhaled corticosteroids, bronchodilators, H2-receptor antagonists, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, anticholinergic agents, immunosuppressants, antipsychotic agents, antibiotics, alcohol abstinence treatment, smoking cessation treatment, blood pressure lowering drugs, lipid lowering drugs, glucose lowering drugs, antiplatelets, anticoagulants), Charlson Comorbidity Index (0, 1–2, 3+), and number of hospital admissions within the last 3 years (0, 1, 2, 3+).

Supplementary Table 4.

Relative Risk of Hospital Admission, Intensive Care Unit Admission, Mechanical Ventilation, or Death for Current, Former, or Never Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors

| Outcome | Current PPI use |

Former PPI use |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | Risk (%) | Events | Risk (%) | Relative risk | |

| Crude | |||||

| Death | 269/4473 | 6.0 (5.3–6.7) | 297/19,338 | 1.5 (1.4–1.7) | 3.92 (3.33–4.60) |

| ICU admission | 118/4473 | 2.6 (2.2–3.1) | 203/19,338 | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 2.51 (2.01–3.15) |

| ICU or death | 353/4473 | 7.9 (7.1–8.7) | 454/19,338 | 2.3 (2.1–2.6) | 3.36 (2.94–3.85) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 68/4473 | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) | 130/19,338 | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 2.26 (1.69–3.03) |

| Hospital admission | 995/4473 | 22.2 (21.0–23.5) | 1848/19,338 | 9.6 (9.1–10.0) | 2.33 (2.17–2.50) |

| Matched | |||||

| Death | 232/4326 | 5.4 (4.7–6.0) | 205/4326 | 4.7 (4.1–5.4) | 1.13 (0.94–1.36) |

| ICU admission | 107/4326 | 2.5 (2.0–2.9) | 106/4326 | 2.5 (2.0–2.9) | 1.01 (0.77–1.32) |

| ICU or death | 311/4326 | 7.2 (6.4–8.0) | 282/4326 | 6.5 (5.8–7.3) | 1.10 (0.94–1.29) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 63/4326 | 1.5 (1.1–1.8) | 70/4326 | 1.6 (1.2–2.0) | 0.90 (0.64–1.26) |

| Hospital admission | 905/4326 | 20.9 (19.7–22.1) | 835/4326 | 19.3 (18.1–20.5) | 1.08 (1.00–1.18) |

| Outcome | Former PPI use |

Never PPI use |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | Risk (%) | Events | Risk (%) | Relative risk | |

| Crude | |||||

| Death | 297/19,338 | 1.5 (1.4–1.7) | 280/59,413 | 0.5 (0.4–0.5) | 3.26 (2.77–3.83) |

| ICU admission | 203/19,338 | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 254/59,413 | 0.4 (0.4–0.5) | 2.46 (2.04–2.95) |

| ICU or death | 454/19,338 | 2.3 (2.1–2.6) | 487/59,413 | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 2.86 (2.52–3.25) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 130/19,338 | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 145/59,413 | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 2.75 (2.18–3.49) |

| Hospital admission | 1848/19,338 | 9.6 (9.1–10.0) | 2145/59,413 | 3.6 (3.5–3.8) | 2.65 (2.49–2.81) |

| Matched | |||||

| Death | 177/18,381 | 1.0 (0.8–1.1) | 256/18,381 | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | 0.69 (0.57–0.84) |

| ICU admission | 170/18,381 | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 182/18,381 | 1.0 (0.8–1.1) | 0.93 (0.76–1.15) |

| ICU or death | 312/18,381 | 1.7 (1.5–1.9) | 401/18,381 | 2.2 (2.0–2.4) | 0.78 (0.67–0.90) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 109/18,381 | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) | 106/18,381 | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) | 1.03 (0.79–1.34) |

| Hospital admission | 1471/18,381 | 8.0 (7.6–8.4) | 1381/18,381 | 7.5 (7.1–7.9) | 1.07 (0.99–1.14) |

ICU, intensive care unit; PPI, proton pump inhibitor use.

Supplementary Table 5.

Relative Risk of Hospital Admission, Intensive Care Unit Admission, Mechanical Ventilation, or Death According to Dose of Proton Pump Inhibitors

| Outcome | Current PPI use |

Never PPI use |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | Risk (%) | Events | Risk (%) | Relative risk | |

| Crude | |||||

| Death | |||||

| Low dose | 90/1631 | 5.5 (4.4–6.6) | 280/59,413 | 0.5 (0.4–0.5) | 11.71 (9.28–14.77) |

| High dose | 179/2842 | 6.3 (5.4–7.2) | 280/59,413 | 0.5 (0.4–0.5) | 13.36 (11.12–16.06) |

| ICU admission | |||||

| Low dose | 29/1631 | 1.8 (1.1–2.4) | 254/59,413 | 0.4 (0.4–0.5) | 4.16 (2.84–6.09) |

| High dose | 89/2842 | 3.1 (2.5–3.8) | 254/59,413 | 0.4 (0.4–0.5) | 7.33 (5.77–9.30) |

| ICU or death | |||||

| Low dose | 112/1631 | 6.9 (5.6–8.1) | 487/59,413 | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 8.38 (6.86–10.23) |

| High dose | 241/2842 | 8.5 (7.5–9.5) | 487/59,413 | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 10.35 (8.91–12.02) |

| Mechanical ventilation | |||||

| Low dose | 13/1631 | 0.8 (0.4–1.2) | 145/59,413 | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 3.27 (1.86–5.75) |

| High dose | 55/2842 | 1.9 (1.4–2.4) | 145/59,413 | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 7.93 (5.83–10.79) |

| Hospital admission | |||||

| Low dose | 319/1631 | 19.6 (17.6–21.5) | 2145/59,413 | 3.6 (3.5–3.8) | 5.42 (4.87–6.03) |

| High dose | 676/2842 | 23.8 (22.2–25.4) | 2145/59,413 | 3.6 (3.5–3.8) | 6.59 (6.10–7.12) |

| Matched | |||||

| Death | |||||

| Low dose | 64/1479 | 4.3 (3.3–5.4) | 189/3955 | 4.8 (4.1–5.4) | 0.91 (0.69–1.19) |

| High dose | 102/2476 | 4.1 (3.3–4.9) | 189/3955 | 4.8 (4.1–5.4) | 0.86 (0.68–1.09) |

| ICU admission | |||||

| Low dose | 26/1479 | 1.8 (1.1–2.4) | 95/3955 | 2.4 (1.9–2.9) | 0.73 (0.48–1.12) |

| High dose | 66/2476 | 2.7 (2.0–3.3) | 95/3955 | 2.4 (1.9–2.9) | 1.11 (0.81–1.51) |

| ICU or death | |||||

| Low dose | 84/1479 | 5.7 (4.5–6.9) | 260/3955 | 6.6 (5.8–7.3) | 0.86 (0.68–1.10) |

| High dose | 151/2476 | 6.1 (5.2–7.0) | 260/3955 | 6.6 (5.8–7.3) | 0.93 (0.76–1.13) |

| Mechanical ventilation | |||||

| Low dose | 13/1479 | 0.9 (0.4–1.4) | 55/3955 | 1.4 (1.0–1.8) | 0.63 (0.35–1.15) |

| High dose | 42/2476 | 1.7 (1.2–2.2) | 55/3955 | 1.4 (1.0–1.8) | 1.22 (0.82–1.82) |

| Hospital admission | |||||

| Low dose | 250/1479 | 16.9 (15.0–18.8) | 650/3955 | 16.4 (15.3–17.6) | 1.03 (0.90–1.17) |

| High dose | 484/2476 | 19.5 (18.0–21.1) | 650/3955 | 16.4 (15.3–17.6) | 1.19 (1.07–1.32) |

ICU, intensive care unit; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Supplementary Table 6.

Relative Risk of Hospital Admission, Intensive Care Unit Admission, Mechanical Ventilation, or Death According to Use of the Different Classes of Proton Pump Inhibitors

| Outcome | Lansoprazole |

Pantoprazole |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | Risk (%) | Events | Risk (%) | Relative risk | |

| Crude | |||||

| Death | 40/833 | 4.8 (3.3–6.3) | 187/2607 | 7.2 (6.2–8.2) | 0.67 (0.48–0.93) |

| ICU admission | 25/833 | 3.0 (1.8–4.2) | 71/2607 | 2.7 (2.1–3.3) | 1.10 (0.70–1.73) |

| ICU or death | 55/833 | 6.6 (4.9–8.3) | 237/2607 | 9.1 (8.0–10.2) | 0.73 (0.55–0.96) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 12/833 | 1.4 (0.6–2.2) | 41/2607 | 1.6 (1.1–2.1) | 0.92 (0.48–1.73) |

| Hospital admission | 180/833 | 21.6 (18.8–24.4) | 633/2607 | 24.3 (22.6–25.9) | 0.89 (0.77–1.03) |

| Matched | |||||

| Death | 38/829 | 4.6 (3.2–6.0) | 37/829 | 4.5 (3.1–5.9) | 1.03 (0.66–1.60) |

| ICU admission | 24/829 | 2.9 (1.8–4.0) | 23/829 | 2.8 (1.7–3.9) | 1.04 (0.59–1.83) |

| ICU or death | 53/829 | 6.4 (4.7–8.1) | 52/829 | 6.3 (4.6–7.9) | 1.02 (0.70–1.48) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 12/829 | 1.4 (0.6–2.3) | 15/829 | 1.8 (0.9–2.7) | 0.80 (0.38–1.70) |

| Hospital admission | 178/829 | 21.5 (18.7–24.3) | 195/829 | 23.5 (20.6–26.4) | 0.91 (0.76–1.09) |

| Outcome | Omeprazole |

Pantoprazole |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | Risk (%) | Events | Risk (%) | Relative risk | |

| Crude | |||||

| Death | 22/749 | 2.9 (1.7–4.1) | 192/2616 | 7.3 (6.3–8.3) | 0.40 (0.26–0.62) |

| ICU admission | 14/749 | 1.9 (0.9–2.8) | 73/2616 | 2.8 (2.2–3.4) | 0.67 (0.38–1.18) |

| ICU or death | 34/749 | 4.5 (3.0–6.0) | 242/2616 | 9.3 (8.1–10.4) | 0.49 (0.35–0.70) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 11/749 | 1.5 (0.6–2.3) | 41/2616 | 1.6 (1.1–2.0) | 0.94 (0.48–1.81) |

| Hospital admission | 126/749 | 16.8 (14.1–19.5) | 640/2616 | 24.5 (22.8–26.1) | 0.69 (0.58–0.82) |

| Matched | |||||

| Death | 22/747 | 2.9 (1.7–4.2) | 37/747 | 5.0 (3.4–6.5) | 0.59 (0.35–1.00) |

| ICU admission | 14/747 | 1.9 (0.9–2.8) | 14/747 | 1.9 (0.9–2.8) | 1.00 (0.48–2.08) |

| ICU or death | 34/747 | 4.6 (3.1–6.0) | 44/747 | 5.9 (4.2–7.6) | 0.77 (0.50–1.19) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 11/747 | 1.5 (0.6–2.3) | 9/747 | 1.2 (0.4–2.0) | 1.22 (0.51–2.93) |

| Hospital admission | 126/747 | 16.9 (14.2–19.6) | 125/747 | 16.7 (14.1–19.4) | 1.01 (0.80–1.26) |

| Outcome | Esomeprazole |

Pantoprazole |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | Risk (%) | Events | Risk (%) | Relative risk | |

| Crude | |||||

| Death | 21/324 | 6.5 (3.8–9.2) | 192/2614 | 7.3 (6.3–8.3) | 0.88 (0.57–1.36) |

| ICU admission | 8/324 | 2.5 (0.8–4.2) | 73/2614 | 2.8 (2.2–3.4) | 0.88 (0.43–1.82) |

| ICU or death | 28/324 | 8.6 (5.6–11.7) | 242/2614 | 9.3 (8.1–10.4) | 0.93 (0.64–1.36) |

| Mechanical ventilation | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.79 (0.28–2.18) |

| Hospital admission | 65/324 | 20.1 (15.7–24.4) | 639/2614 | 24.4 (22.8–26.1) | 0.82 (0.65–1.03) |

| Matched | |||||

| Death | 21/324 | 6.5 (3.8–9.2) | 22/324 | 6.8 (4.1–9.5) | 0.95 (0.54–1.70) |

| ICU admission | 8/324 | 2.5 (0.8–4.2) | 8/324 | 2.5 (0.8–4.2) | 1.00 (0.38–2.63) |

| ICU or death | 28/324 | 8.6 (5.6–11.7) | 27/324 | 8.3 (5.3–11.3) | 1.04 (0.63–1.72) |

| Mechanical ventilation | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.80 (0.22–2.95) |

| Hospital admission | 65/324 | 20.1 (15.7–24.4) | 63/324 | 19.4 (15.1–23.8) | 1.03 (0.76–1.41) |

ICU, intensive care unit; NA (not applicable), refers to no observed events or number of events below 5 not presented because of patient confidentiality considerations.

Supplementary Table 7.

Characteristics of Studies Included in the Meta-analyses

| Study | Design | Population-based | Country or region | Timing of data collection | Mean or median age (y) | No. of subjects | Current PPI users, n (%) | Confounder control in design | Confounder adjustment in analysis | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vila-Corcoles | Cohort | Yes | Spain | May 1–Apr 3, 2020 | 71 | 34,936 | 11,807 (34%) | No | No | Risk of infection |

| Huh | Case-control | Yes | Korea | Up to Apr 8, 2020 | 49 | 65,149 | 14,827 (23%) | No | Yes | Risk of infection |

| Xiang | Cohort | Yes | UK | Jan–Nov 6, 2020 | 68 | 30,835 | 10,724 (33%) | No | Yes | Risk of infection |

| Almario | Cohort | Yes | USA | May 3–Jun 24, 2020 | NR | 53,130 | 16,547 (31%) | No | Yes | Risk of infection |

| Tarlow | Cohort | No | USA | NR | NR | 84,325 | 18,240 (22%) | No | No | Risk of infection |

| Blanc | Case-control | No | France | Up to Apr 8, 2020 | 84 | 179 | 63 (35%) | No | No | Risk of infection |

| Ullah | Cohort | No | UK | Feb 12–Jun 12, 2020 | 57 | 15,586 | 4533 (29%) | No | Yes | Risk of infection; |

| 67 | 212 | 87 (41%) | No | Yes | mortality | |||||

| Lee | Matched case-control | Yes | Korea | Jan 1–May 15, 2020 | 56 | 27,746 | 13,873 (50%) | Yes | Yes | Risk of infection |

| Cohort | 50 | 534 | 267 (50%) | Yes | Yes | Severe clinical outcomesa | ||||

| Israelsen | Matched case-control | Yes | Denmark | Feb–Dec 1, 2020 | 36 | 416,023 | 22,026 (5%) | Yes | Yes | Risk of infection |

| Cohort | 60 | 7910 | 3955 (50%) | Yes | No | Severe clinical outcomes; mortality | ||||

| Ramachandran | Cohort | No | USA | Mar 1–Apr 25, 2020 | 66 | 295 | 46 (48%) | No | No | Severe clinical outcomes; mortality |

| Luxenburger | Cohort | No | Germany | NR | 65 | 152 | 62 (41%) | No | No | Secondary infection; ARDS; mortality |

| Fan | Cohort | Yes | UK | Mar 16–Jun 29, 2020 | NR | 3032 | 1354 (45%) | Yes | No | Risk of infection; mortality |

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; NR, not reported; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Severe clinical outcomes include mechanical ventilation, intensive care unit admission, or death.

References

- 1.Gulmez S.E., Holm A., Frederiksen H., et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors and the risk of community-acquired pneumonia: a population-based case-control study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:950–955. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.9.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lambert A.A., Lam J.O., Paik J.J., et al. Risk of community-acquired pneumonia with outpatient proton-pump inhibitor therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herzig S.J., Howell M.D., Ngo L.H., et al. Acid-suppressive medication use and the risk for hospital-acquired pneumonia. JAMA. 2009;301:2120–2128. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darnell M.E.R., Subbarao K., Feinstone S.M., et al. Inactivation of the coronavirus that induces severe acute respiratory syndrome, SARS-CoV. J Virol Methods. 2004;121:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiao F., Tang M., Zheng X., et al. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1831–1833.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Almario C.V., Chey W.D., Spiegel B.M.R. Increased risk of COVID-19 among users of proton pump inhibitors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1707–1715. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee S.W., Ha E.K., Yeniova A.Ö., et al. Severe clinical outcomes of COVID-19 associated with proton pump inhibitors: a nationwide cohort study with propensity score matching. Gut. 2020 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou J., Wang X., Lee S., et al. Proton pump inhibitor or famotidine use and severe COVID-19 disease: a propensity score-matched territory-wide study. Gut. 2020 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kow C.S., Hasan S.S. Use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of adverse clinical outcomes from COVID-19: a meta-analysis. J Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1111/joim.13183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li G.-F., An X.-X., Yu Y., et al. Do proton pump inhibitors influence SARS-CoV-2 related outcomes? a meta-analysis. Gut. 2020 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pottegård A., Kristensen K.B., Reilev M., et al. Existing data sources in clinical epidemiology: the Danish COVID-19 cohort. Clin Epidemiol. 2020;12:875–881. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S257519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ullah A.D., Kocher H., Chelala C. COVID-19 in patients with hepatobiliary and pancreatic diseases in East London: a single-centre cohort study. Pancreatology. 2020;20:e15. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vila-Corcoles A., Satue-Gracia E., Ochoa-Gondar O., et al. Use of distinct anti-hypertensive drugs and risk for COVID-19 among hypertensive people: a population-based cohort study in Southern Catalonia, Spain. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2020;22:1379–1388. doi: 10.1111/jch.13948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tarlow B., Gubatan J., Khan M.A., et al. Are proton pump inhibitors contributing to SARS-COV-2 infection? Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1920–1921. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huh K., Ji W., Kang M., et al. Association of previous medications with the risk of COVID-19: a nationwide claims-based study from South Korea. medRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiang Y., Wong K.C.Y., Hon-Cheong S. Exploring drugs and vaccines associated with altered risks and severity of COVID-19: a UK Biobank cohort study of all ATC level-4 drug categories. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13091514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blanc F., Waechter C., Vogel T., et al. Interest of proton pump inhibitors in reducing the occurrence of COVID-19: a case-control study. Preprints. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan X., Liu Z., Miyata T., et al. Effect of acid suppressants on the risk of COVID-19: a propensity score-matched study using UK Biobank. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:455–458.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramachandran P., Perisetti A., Gajendran M., et al. Pre-hospitalization proton pump inhibitor use and clinical outcomes in COVID-19. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000002013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luxenburger H., Sturm L., Biever P., et al. Treatment with proton pump inhibitors increases the risk of secondary infections and ARDS in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: coincidence or underestimated risk factor? J Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1111/joim.13121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamal F., Khan M.A., Sharma S., et al. Lack of consistent associations between pharmacologic gastric acid suppression and adverse outcomes in patients with coronavirus disease 2019: meta-analysis of observational studies. Gastroenterology. 2021 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toubasi A.A., AbuAnzeh R.B., Khraisat B.R., et al. A meta-analysis: proton pump inhibitors current use and the risk of coronavirus infectious disease 2019 development and its related mortality. Arch Med Res. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2021.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elmunzer B.J., Spitzer R.L., Foster L.D., et al. Digestive manifestations in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiersinga W.J., Rhodes A., Cheng A.C., et al. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. 2020;324:782–793. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forgacs I., Loganayagam A. Overprescribing proton pump inhibitors. BMJ. 2008;336:2–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39406.449456.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]