Abstract

Background:

Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials test candidate treatments in individuals with biomarker evidence but no cognitive impairment. Participants are required to co-enroll with a knowledgeable study partner, to whom biomarker information is disclosed.

Objective:

We investigated whether reluctance to share biomarker results is associated with viewing the study partner requirement as a barrier to preclinical trial enrollment.

Design:

We developed a nine-item assessment on views toward the study partner requirement and performed in-person interviews based on a hypothetical clinical trial requiring biomarker testing and disclosure.

Setting:

We conducted interviews on campus at the University of California, Irvine.

Participants:

Two hundred cognitively unimpaired older adults recruited from the University of California, Irvine Consent-to-Contact Registry participated in the study.

Measurements:

We used logistic regression models, adjusting for potential confounders, to examine potential associations with viewing the study partner requirement as a barrier to preclinical trial enrollment.

Results:

Eighteen percent of participants reported strong agreement that the study partner requirement was a barrier to enrollment. Ten participants (5%) agreed at any level that they would be reluctant to share their biomarker result with a study partner. The estimated odds of viewing the study partner requirement as a barrier to enrollment were 26 times higher for these participants (OR=26.3, 95% CI 4.0, 172.3), compared to those who strongly disagreed that they would be reluctant to share their biomarker result. Overall, participants more frequently agreed with positive statements than negative statements about the study partner requirement, including 76% indicating they would want their study partner with them when they learned biomarker results.

Conclusions:

This is one of the first studies to explore how potential preclinical Alzheimer’s disease trial participants feel about sharing their personal biomarker information with a study partner. Most participants viewed the study partner as an asset to trial enrollment, including having a partner present during biomarker disclosure.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, biomarker, disclosure

INTRODUCTION

The urgency to discover effective therapies for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) continues to increase as the population ages. In an effort to identify treatments that can delay the onset of symptomatic disease and reduce the incidence of dementia, clinical trials are testing candidate treatments in preclinical disease. Preclinical AD trials enroll individuals who demonstrate no cognitive impairment, but have evidence of a biomarker for AD (e.g., elevated brain beta amyloid) (1). Performing AD biomarker testing in asymptomatic populations presents unique challenges in preclinical AD trials. Though initial studies suggest that biomarker disclosure does not result in medical or psychological adverse events (i.e., depression, anxiety, suicidality) (2–5), there remain potential social consequences, such as implications to health insurance and job discrimination and stigmatization from family and friends (6). Like AD dementia trials, preclinical AD trials require participants to co-enroll with a knowledgeable informant, or “study partner,” most often a family member or close friend. Therefore, preclinical AD trials not only require that an individual learn their biomarker status, but also that they share this information with at least one other person.

Preclinical AD trial participants are cognitively unimpaired, functionally independent, and able to provide informed consent autonomously. Yet, study partners may be essential to measuring cognitive and functional decline and ensuring trial data integrity (7–11). Study partners may also play a role in participant safety, helping participants cope with learning biomarker status (12, 13). Ultimately, the role of study partners in preclinical AD trials may anticipate a future clinical practice in which AD is diagnosed before symptom onset and long-term planning and social support are essential (14, 15).

The study partner requirement may present a barrier to efficient enrollment and timely completion of preclinical AD trials. Potential trial participants may be unable or unwilling to identify a study partner (16). There are additional logistical barriers to recruitment of individuals with non-spouse study partners (e.g., adult child, close friend), which may limit trial generalizability (17). Though few studies have explored how trial participants feel about sharing their personal biomarker information with a study partner, it is reasonable to hypothesize that this may be yet another barrier to recruitment. In support of this hypothesis, a recent randomized study of preclinical AD trial enrollment decisions found that participants considering a hypothetical trial that required biomarker disclosure rated the study partner requirement as a more important barrier to enrollment than did participants considering a hypothetical trial with no biomarker disclosure (16).

The objective of this study was to investigate the role of the study partner requirement in preclinical AD trial enrollment decisions. We quantified the extent to which reluctance to share biomarker test results with a study partner was associated with viewing the study partner requirement as a barrier to enrollment. We also assessed other aspects of participant attitudes toward the study partner requirement, including perceived benefits of the requirement, and compared the frequencies of positive and negative attitudes among potential preclinical AD trial participants.

METHODS

Participants.

The planned sample size for this study was N=200 participants. Eligibility criteria for this study mirrored those for current preclinical AD trials (18, 19) and were assessed based on data provided by participants when enrolling in the University of California, Irvine Consent-to-Contact (C2C) Registry (20) and at in-person visits. Participants were age 60 to 85 and able to complete the interview in English. When recruiting from our local registry, we restricted to individuals who had self-reported willingness to be contacted about studies involving an investigational medication, positron emission tomography (PET), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Exclusion criteria were a diagnosis of dementia or another neurological or psychiatric disorder, cancer in the previous five years (except basal and squamous cell carcinoma), and auditory or visual impairments that could prevent the conduct of the study interview. Participants were required to score 23 or higher on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) at the in-person interview (21, 22).

Queries of the C2C Registry identified 369 eligible registrants to whom we sent email invitations to enroll in the interview study. Interested email recipients could click a link to an enrollment website where they could watch an informational video about the study from the lead researcher, review the study informed consent form, and self-schedule their in-person interview. We attempted up to three telephone follow-up calls with individuals who did not respond to email invitations. Once scheduled, participants received a confirmation email with links to review example preclinical AD trial participant and study partner consent forms. The confirmation email included an instructional video describing the example consent forms and what the in-person interview would entail. Interview participants received a $25 gift card to a national retail store for participation in the study.

Example preclinical AD trial.

We asked interviewees to review participant and study partner informed consent forms for an example trial based on preclinical AD trials to date (18, 19). They received the forms via email 72 hours prior to the in-person interview. At the in-person interview, we reviewed the forms again using a standardized script to highlight key components of the trial, including time commitment, biomarker disclosure, drug risks, and the study partner requirement. The trial was described as a five-year study of an oral drug requiring monthly visits to the medical center, six MRIs, and regular physical, neurological, and cognitive evaluations. PET imaging and/or cerebrospinal fluid analysis would identify participants meeting preclinical AD criteria (i.e., elevated brain beta amyloid levels). The primary risks of the treatment were described as skin rash, diarrhea, and liver abnormalities that occurred in about 10% of participants in previous studies. The study partner was defined as a person with whom the participant had at least weekly contact (i.e., in-person, telephone, electronic), had known for at least one year, and could attend four study visits per year to answer questions about the participant’s cognitive and functional abilities.

Data collection.

We performed a mixed-methods interview that took approximately 45 minutes to complete. After completion of informed consent and MoCA screening, we provided general education on preclinical AD and reviewed the consent forms for the example preclinical AD trial. We then assessed participants’ attitudes toward the study partner requirement and likelihood to enroll in the example preclinical AD trial. All data were managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) (23).

Attitudes toward the study partner requirement.

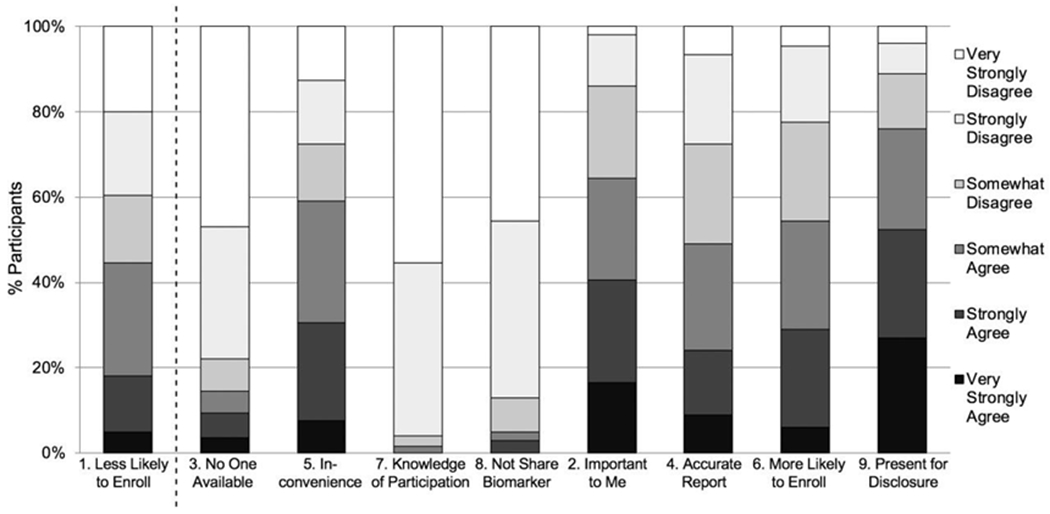

After defining the study partner requirements, we asked participants to identify a person in their life who would be most likely to serve in that role if they were to enroll in a preclinical AD trial. Then, asking participants to keep that person in mind, we administered a nine-item assessment of participant attitudes toward the study partner requirement, developed based on previous studies and review of the literature (Table 1). Specifically, we asked participants to rate their level of agreement with four positive (Statements 2, 4, 6, 9) and five negative statements (Statements 1, 3, 5, 7, 8) on a six-point Likert scale (very strongly disagree, strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, somewhat agree, strongly agree, very strongly agree).

Table 1.

Assessment of participant attitudes toward the study partner requirement

| Statement 1 | The study partner requirement makes me less likely to enroll. |

| Statement 2 | It would be important to me to participate with a study partner. |

| Statement 3 | There is no one with whom I have adequate contact to fill the study partner role. |

| Statement 4 | A study partner would be able to provide more accurate information to the study team about me than I would. |

| Statement 5 | I do not want to inconvenience the person who could be my study partner. |

| Statement 6 | The opportunity to have someone I trust accompany to study visits would make me more likely to enroll. |

| Statement 7 | I would not want the person who could be my study partner to know I was participating in research. |

| Statement 8 | I would not want the person who could be my study partner to know if I had elevated brain amyloid. |

| Statement 9 | I would want the person who could be my study partner with me when I learned my brain amyloid status result. |

Covariates.

Participants provided demographic information, including age, sex, race, ethnicity, education level, and family history of AD when enrolling in the C2C Registry. They also, at that time, completed the Research Attitudes Questionnaire (RAQ) (24) and the Cognitive Function Instrument (CFI) (25), a measure of subjective cognitive performance. During the in-person interview, we administered the 30-item AD Knowledge Scale (ADKS) (26) and the six-item Concerns about AD scale (27).

Data analyses.

We used logistic regression models to examine potential associations with viewing the study partner requirement as a barrier, or Statement 1 on the nine-item assessment (Table 1). Models were adjusted for potential confounding factors, including age, sex, years of education, race, family history of AD, RAQ, CFI, ADKS, and Concerns about AD scores. For the primary analysis, we examined the association between strong agreement (i.e., very strongly agree, strongly agree) with Statement 1 (The study partner requirement makes me less likely to enroll) and reluctance to share biomarker information with a study partner (Statement 8). Our pre-specified plan was to use binary data for the 6-point Likert scale, dichotomizing those who very strongly agreed or strongly agreed with Statement 8 versus the four remaining Likert levels (somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, strongly disagree, very strongly disagree). Due to sparsity of data indicating agreement with Statement 8, however, we modelled the data collapsing the three levels of agreement into a single category and using independent categories for the three levels of disagreement, with extreme disagreement as a reference group. Since the three levels of disagreement contained 95% (n=190) of total responses to Statement 8, they were not collapsed. The decision to collapse the three agreement levels (and to not collapse the three disagreement levels) was made without knowledge of covariate associations with the outcome.

In secondary analyses, we stratified the data by whether the participant indicated a spouse versus a non-spouse study partner. We then examined the association between Statement 1 and each additional statement on the study partner attitudes assessment. For positive statements (Statements 2, 4, 6, 9), we examined the association with strong disagreement (i.e., very strongly disagreed or strongly disagreed) with Statement 1. For remaining negative statements (Statements 3, 5, 7), we examined the association with strong agreement (i.e., very strongly agreed or strongly agreed) with Statement 1. For all statements, we dichotomized responses by collapsing the three levels of agreement and the three levels of disagreement.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics.

We successfully recruited N=200 of 369 potentially eligible C2C Registry participants, 80% of whom self-scheduled their interview on the study website with no follow-up calls required. Of the 169 registrants who did not participate, we determined 11% to be ineligible, 47% declined, and we were unable to reach 42%. There were no apparent demographic differences between those who did and those who did not enroll in the study (Table 2). Most participants were non-Latino white, highly educated, and female. The average age of participants was 72 years, and a quarter reported a family history of AD.

Table 2.

Demographics.

| Characteristic | Participants (n=200) | Non-Participants (n=169) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean years (SD) [Range] | 72.1 (5.5) [60-85] | 72.4 (5.6) [60-85] |

| Years of Education, mean years (SD) [Range] | 16.4 (2.5) [4-23] | 16.4 (2.2) [12-24] |

| Race, n (%): | ||

| • White | 178 (89) | 153 (91) |

| • Asian or Pacific Islander | 9 (4.5) | 9 (5) |

| • Black | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| • Other | 11 (5.5) | 7 (4) |

| Ethnicity, n (%): | ||

| • Non-Latino | 191 (95.5) | 135 (80) |

| • Latino | 6 (3) | 9 (5) |

| • Missing/Refuse | 3 (1.5) | 25 (15) |

| Sex: Female, n (%) | 124 (62) | 100 (59) |

| Family History of AD, n (%) | 54 (27) | 55 (33) |

| RAQ, mean (SD) [Range] | 29.3 (3.6) [7-35] | 29.8 (3.5) [21-35] |

| CFI, mean (SD) [Range] | 2.1 (2.0) [0-10.5] | 2.7 (2.7) [0-12.5] |

| MoCA, mean (SD) [Range] | 27.2 (1.9) [23-30] | |

| Concerns about AD, mean (SD) [Range] | 18.7 (4.7) [6-29] | |

| ADKS, mean (SD) [Range] | 25.9 (2.7) [17-30] | |

Willingness to share AD biomarker results.

Eighteen percent of participants reported strong agreement that the study partner requirement would be a barrier to enrollment (Statement 1; Figure 1). Ten participants (5%) agreed at any level that they would be reluctant to share their biomarker result with a study partner (Statement 8). For those who agreed that they would be reluctant to share their biomarker result, the estimated odds of viewing the study partner requirement as a barrier to enrollment were 26 times that of individuals who very strongly disagreed that they would be reluctant to share their biomarker result (OR=26.3, 95% CI 4.0, 172.3) (Table 3). Even those who somewhat disagreed (n=16; 8%) or strongly disagreed (n=83; 42%) that they would be reluctant to share their biomarker result had odds of viewing the study partner requirement as a barrier that were estimated to be 6.5 (OR=6.5, 95% CI 1.5, 28.7) and 3 times (OR=3.1, 95% CI 1.1, 8.8) greater than those who very strongly disagreed (n=91; 46%), respectively. No other covariate in the model was significantly associated with viewing the study partner requirement as a barrier to enrollment.

Figure 1. Participant level of agreement with negative (# 1, 3, 5, 7, 8) and positive (# 2, 4, 6, 9) statements about the study partner requirement.

Participants rated their level of agreement on a 6-point Likert scale (i.e., very strongly disagree, strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, somewhat agree, strongly agree, very strongly agree) with nine statements related to the study partner requirement in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials (Table 1).

Table 3.

Association of reluctance to share biomarker result (Statement 8) with viewing the study partner requirement as a barrier to enrollment (Statement 1).

| Covariate | Odds Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Reluctant to share biomarker result (Statement 8) | ||

| • Agree | 26.3 | (4.0, 172.3) |

| • Somewhat disagree | 6.5 | (1.5, 28.7) |

| • Strongly disagree | 3.1 | (1.1, 8.8) |

| • Very strongly disagree | 1 | - |

| Age | 1.0 | (0.9, 1.1) |

| Male | 0.6 | (0.2, 1.5) |

| Years of education | 1.2 | (0.9, 1.4) |

| Non-Caucasian race | 0.4 | (0.1, 2.3) |

| Family history of AD | 0.5 | (0.1, 1.8) |

| ADKS | 0.9 | (0.7, 1.0) |

| CFI | 1.1 | (0.9, 1.4) |

| RAQ | 1.2 | (1.0, 1.4) |

| Concern for AD | 0.9 | (0.8, 1.1) |

When asked who would be most likely to serve as their study partner, 47.5% of participants reported a spouse and 52.5% reported a non-spouse (28.5% friend, 15.5% adult child, 6% sibling, 2.5% other). Twelve percent of those with a spouse partner compared to 24% of those with a non-spouse partner viewed the study partner requirement as a barrier to enrollment. Three percent of those with a spouse partner compared to 7% of those with a non-spouse partner agreed at any level that they were reluctant to share their biomarker results. We were unable to estimate logistic regression model parameters due to limited data in the agreement cells after splitting the data by partner type.

Attitudes toward the study partner requirement.

Among the remaining negative statements about the study partner requirement, 15% of participants (2% of those who indicated a spouse partner; 26% of those who indicated a non-spouse partner) reported they had no one available to serve as their study partner; 59% (44% spouse; 72% non-spouse) were concerned about nconveniencing another person; and 2% (1% spouse; 2% non-spouse) reported they would not want their partner to know about their participation in research (Figure 1). Among positive statements about the study partner requirement, 55% of participants (62% spouse; 48% non-spouse) reported the opportunity to have a partner would make them more likely to enroll; 65% (77% spouse; 53% non-spouse) reported it would be important to them to have a study partner; 49% (62% spouse; 37% non-spouse) agreed a study partner would provide more accurate information about the participant than he/she would; and 76% (89% spouse; 65% non-spouse) indicated they would want their study partner present during AD biomarker disclosure.

Examination of potential associations between agreement with negative statements (Statements 3, 5, 7) and viewing the study partner requirement as a barrier to enrollment (Statement 1) resulted in wide confidence intervals (Table 4). The odds ratio point estimate was highest for Statement 7, not wanting a study partner to know about research participation, with which no participant reported strong agreement. Higher frequencies of participant agreement with positive statements (Statements 2, 4, 6, 9) resulted in more precise estimation of associations with disagreement with Statement 1. Statement 9, wanting the study partner present during biomarker disclosure, was most strongly associated with strong disagreement that the partner requirement is a barrier.

Table 4.

Associations of additional statements with viewing the study partner requirement as a barrier to enrollment (Statement 1).

| Statement | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Do not have anyone available (Statement 3)* | 17.8 | (5.5, 57.8) |

| Would not want to inconvenience another person (Statement 5)* | 5.5 | (1.8, 17.1) |

| Would not want study partner to know about participation (Statement 7)* | 41.2 | (2.4, 701.1) |

| It is important to have a study partner (Statement 2)† | 13.3 | (4.9, 35.8) |

| Study partner would provide more accurate report (Statement 4)† | 4.2 | (2.0, 8.9) |

| Would be more likely to enroll with study partner (Statement 6)† | 8.0 | (3.5, 18.2) |

| Would want study partner present for disclosure (Statement 9)† | 14.2 | (3.7, 53.7) |

Reference = strong agreement that the study partner requirement is a barrier (Statement 1)

Reference = strong disagreement that the study partner requirement is a barrier (Statement 1)

DISCUSSION

These results represent an important contribution to the field’s understanding of the study partner requirement in the newest types of AD clinical trials, those enrolling participants meeting criteria for preclinical AD (15, 28). Potential participants for preclinical AD trials infrequently had concerns about sharing their biomarker results with individuals who could serve as their study partners. Only 10 participants (5%) in this sample agreed at any level that they would not want to share biomarker information with a partner. Instead, the majority of participants (76%) indicated that they would want their study partner with them when they learned AD biomarker results. The results suggest that the benefits may outweigh the barriers associated with the study partner requirement in preclinical AD trials (15).

Though few participants did not wish to share their biomarker results, these individuals were substantially more likely to view the study partner requirement as a barrier to enrollment. Caution must therefore be taken when considering enrolling similar individuals in trials. The most straightforward option for these people is to decline participation. Yet, there may be reasons to be more inclusive, especially if this sentiment is prominent among individuals not well represented in the current study or in preclinical AD trials, such as racial and ethnic minorities. Investigators may need to consider ways to address this concern through education and counseling, while respecting the autonomous choices of these participants.

Most participants viewed the study partner requirement as an asset to preclinical AD trials. This included the belief that partners might provide valuable data to investigators and meaningful support to participants during biomarker disclosure. The latter may be particularly important to instructing biomarker disclosure processes (29), given that many preclinical AD trial participants are unaware of the option to have their study partner with them when they learn their biomarker result (13).

Involving partners in disclosure and trial conduct may anticipate a future clinical practice in preclinical AD. Preclinical diagnosis, in the absence of disease-arresting therapies, will be an opportunity to engage in lifestyle risk reduction strategies, management of financial and legal affairs, and long-term planning toward residential and care choices. For most individuals, this planning will be strongly facilitated by involving family and other members of social support networks. Preclinical AD trials should try to characterize these types of interactions and the value of both the preclinical AD diagnosis and the involvement of others in subsequent decision-making.

Though the requirement of sharing AD biomarker results with a study partner was infrequently problematic for participants in this study, the partner requirement did pose barriers to enrollment, particularly for those with a non-spouse partner. More than half of participants in this study, and 72% of those with a non-spouse partner, reported concern about inconveniencing another person. Similarly, 26% of those who reported a non-spouse partner, compared to 2% of those with a spouse partner, indicated that they simply did not have someone who could fill the role. These findings confirm that the requirement may produce unwanted sample bias in trials and necessitate approaches to enable participation by those for whom the requirement is a barrier. Alternative options for study partner visits, such as video-conferencing and weekend or evening appointments may alleviate some of these challenges. Greater incentives for enrollment, such as paid time off for research participation – both for participants and partners – should also be pursued (28). Alternatively, developing a national study partner registry for people interested in volunteering or being compensated to serve as a study partner for participants with no one available could help accelerate accrual and diversify trial samples.

We note some limitations of this study. The interview presented a hypothetical scenario and participant responses may not predict actual behaviors around preclinical AD trial enrollment. In particular, participants in this study did not learn biomarker results and whether attitudes toward disclosure and sharing could conceivably change in that setting requires further study (30). Each participant was presented the study partner assessment items in the same order (rather than in randomized order), creating potential for an order effect. Participants were recruited from a local recruitment registry and may not be representative of the general population. Participants were predominantly non-Latino white. Whether these results might differ in specific under-represented racial or ethnic groups is unknown. Additional studies should focus on diverse enrollment to ensure perspectives of all groups are taken into account when designing future preclinical AD trials. Data were more homogenous than anticipated, forcing adjustment of our analytic strategies from those prespecified. In this case, that necessity supports the conclusion of the study—that few participants felt strongly unwilling to share biomarker results with a study partner.

Recruitment of asymptomatic older adults to preclinical AD clinical trials presents unique challenges, including the requirements of biomarker disclosure and co-enrollment with a study partner. This is one of the first studies to explore how potential AD trial participants feel about sharing their personal biomarker information with a study partner. Very few participants were concerned about sharing this personal information with the person who could serve as their study partner. Instead, most participants viewed the study partner as an asset to preclinical AD trial enrollment, including having a partner present during biomarker disclosure. These results suggest the study partner requirement in preclinical AD trials is perceived as a benefit rather than a barrier to enrollment among potential trial participants.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the participants in this study for their time and contributions and Mr. Dan Hoang for his support with study informatics.

FUNDING

This work was supported by a NIA R21 AG056931. CGC, DLG, and JDG are supported by NIA AG016573. JDG is also supported by NCATS UL1 TR001414. The University of California, Irvine Consent-to-Contact (UCI C2C) Registry was funded by a gift from Health Care Partners, Inc. The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the preparation of the manuscript; or in the review or approval of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dubois B, Hampel H, Feldman HH, Scheltens P, Aisen P, Andrieu S, et al. Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: Definition, natural history, and diagnostic criteria. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(3):292–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burns JM, Johnson DK, Liebmann EP, Bothwell RJ, Morris JK, Vidoni ED. Safety of disclosing amyloid status in cognitively normal older adults. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(9):1024–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim YY, Maruff P, Getter C, Snyder PJ. Disclosure of positron emission tomography amyloid imaging results: A preliminary study of safety and tolerability. Alzheimers Dement. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wake T, Tabuchi H, Funaki K, Ito D, Yamagata B, Yoshizaki T, et al. Disclosure of Amyloid Status for Risk of Alzheimer Disease to Cognitively Normal Research Participants With Subjective Cognitive Decline: A Longitudinal Study. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2020;35:1533317520904551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wake T, Tabuchi H, Funaki K, Ito D, Yamagata B, Yoshizaki T, et al. The psychological impact of disclosing amyloid status to Japanese elderly: a preliminary study on asymptomatic patients with subjective cognitive decline. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(5):635–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karlawish J Addressing the ethical, policy, and social challenges of preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2011;77(15):1487–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryan MM, Grill JD, Gillen DL, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I. Participant and study partner prediction and identification of cognitive impairment in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: study partner vs. participant accuracy. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;11(1):85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nosheny RL, Jin C, Neuhaus J, Insel PS, Mackin RS, Weiner MW, et al. Study partner-reported decline identifies cognitive decline and dementia risk. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2019;6(12):2448–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amariglio RE, Donohue MC, Marshall GA, Rentz DM, Salmon DP, Ferris SH, et al. Tracking Early Decline in Cognitive Function in Older Individuals at Risk for Alzheimer Disease Dementia: The Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Cognitive Function Instrument. JAMA Neurol. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norton DJ, Amariglio R, Protas H, Chen K, Aguirre-Acevedo DC, Pulsifer B, et al. Subjective memory complaints in preclinical autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2017;89(14):1464–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caselli RJ, Chen K, Locke DE, Lee W, Roontiva A, Bandy D, et al. Subjective cognitive decline: Self and informant comparisons. Alzheimers Dement. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mozersky J, Sankar P, Harkins K, Hachey S, Karlawish J. Comprehension of an Elevated Amyloid Positron Emission Tomography Biomarker Result by Cognitively Normal Older Adults. JAMA Neurol. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grill JD, Cox CG, Harkins K, Karlawish J. Reactions to learning a “not elevated” amyloid PET result in a preclinical Alzheimer’s disease trial. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10(1):125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Largent EA, Karlawish J. Preclinical Alzheimer Disease and the Dawn of the Pre-Caregiver. JAMA Neurol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grill JD, Karlawish J. Study partners should be required in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease trials. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017;9(1):93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grill JD, Zhou Y, Elashoff D, Karlawish J. Disclosure of amyloid status is not a barrier to recruitment in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;39:147–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grill JD, Raman R, Ernstrom K, Aisen P, Karlawish J. Effect of study partner on the conduct of Alzheimer disease clinical trials. Neurology. 2013;80(3):282–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sperling RA, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, Karlawish J, Donohue M, Salmon DP, et al. The A4 study: stopping AD before symptoms begin? Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(228):228fs13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henley D, Raghavan N, Sperling R, Aisen P, Raman R, Romano G. Preliminary Results of a Trial of Atabecestat in Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(15):1483–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grill JD, Hoang D, Gillen DL, Cox CG, Gombosev A, Klein K, et al. Constructing a Local Potential Participant Registry to Improve Alzheimer’s Disease Clinical Research Recruitment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;63(3):1055–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carson N, Leach L, Murphy KJ. A re-examination of Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) cutoff scores. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(2):379–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubright JD, Cary MS, Karlawish JH, Kim SY. Measuring how people view biomedical research: Reliability and validity analysis of the Research Attitudes Questionnaire. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2011;6(1):63–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walsh SP, Raman R, Jones KB, Aisen PS. ADCS Prevention Instrument Project: the Mail-In Cognitive Function Screening Instrument (MCFSI). Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20(4 Suppl 3):S170–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carpenter BD, Balsis S, Otilingam PG, Hanson PK, Gatz M. The Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Scale: development and psychometric properties. Gerontologist. 2009;49(2):236–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts JS, Connell CM. Illness representations among first-degree relatives of people with Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2000;14(3):129–36,Discussion 7-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Largent EA, Karlawish J, Grill JD. Study partners: essential collaborators in discovering treatments for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10(1):101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harkins K, Sankar P, Sperling R, Grill JD, Green RC, Johnson KA, et al. Development of a process to disclose amyloid imaging results to cognitively normal older adult research participants. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7(1):26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Largent EA, Harkins K, van Dyck CH, Hachey S, Sankar P, Karlawish J. Cognitively unimpaired adults’ reactions to disclosure of amyloid PET scan results. PLoS One. 2020;15(2):e0229137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]