Abstract

Behavior analysts acting as supervisors of individuals pursuing Behavior Analyst Certification Board certification are tasked with designing effective and ethical supervision and training systems. Behavior analyst supervisors and their trainees may face challenges fulfilling their responsibilities in the midst of barriers that include competing contingencies, transitions, and interruptions. In this article, we review potential obstacles faced by supervisors in designing effective supervision through site closures and transitions to telepractice as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. We explore related potential barriers faced by trainees serving clients through public school settings, as well as through insurance-funded agencies in the United States. We review some practical solutions and offer tools for supervisors and trainees to consider at this time. We present a template for trainees to help them develop a personalized applied behavior analysis fieldwork plan for their supervision, a client/family needs assessment, and a corresponding trainee needs assessment to assist with adaptations to supervision and service delivery in an individualized manner.

Keywords: Applied behavior analysis fieldwork, Behavior Analyst Certification Board, COVID-19, Supervision, Telepractice, Telehealth

When behavior analysts accept the role of supervisor, “they must take full responsibility for all facets of this undertaking” (Behavior Analyst Certification Board [BACB], , 2014, p. 13, Section 5.0, “Behavior Analysts as Supervisors”). One of the responsibilities of a Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA) in their supervising role is to ethically and effectively design supervision and training (BACB, 2014, section 5.04). Behavior analysts may face challenges in carrying out these tasks in the midst of interruptions and transitions. The BACB (2014) Professional and Ethical Compliance Code for Behavior Analysts (hereafter referred to as the BACB Ethics Code) includes guidance related to interruptions in service provision in Section 2.15 of 2.0 (“Behavior Analysts’ Responsibility to Clients”). Section 2.15(b) states that “behavior analysts make reasonable and timely efforts for facilitating the continuation of behavior analytic services in the event of unplanned interruptions (e.g., due to illness, impairment, unavailability, relocation, disruption of funding, disaster)” (p. 10). An updated BACB Ethics Code will go into effect in 2022 (BACB, 2020a), and readers may refer to a “crosswalk” document made available for support in translating the differences between the two documents (BACB, 2021). Whereas various forms of interruptions and transitions can be expected and anticipated by behavior analysts, the COVID-19 pandemic is an unplanned interruption on an unprecedented scale in terms of the degree to which it has disrupted the delivery of applied behavior analysis (ABA) services and, in turn, the supervision of trainees pursuing certification.

With school and site closures, issued stay-at-home orders, and overall increased public concern regarding COVID-19 (Asmundson & Taylor, 2020; Mertens et al., 2020), supervisors need to acknowledge existing obstacles and take reasonable steps to prevent and remediate dilemmas affecting trainee fieldwork experiences. Trainees pursuing a certification through the BACB are threatened with losing opportunities not only to provide services to their clients but also to accumulate experience hours and supervised observations with clients (refer to the respective certification requirements: BACB, 2019a, 2019b, 2020b). For example, trainees who work in the public school system may suddenly be left with limited possibilities to directly support their clients, families, and staff, presumably affecting their plans to accrue supervised experience hours. Similarly, trainees accruing experience hours in other settings, such as in homes or clinics, may experience challenges in arranging supervised observations with their clients because of social-distancing practices or limited funding resources to support trainee-delivered services via telepractice. With a loss of direct contact with clients, the possibilities for trainees to practice the implementation of various ABA strategies in naturally situated contexts will consequently decrease.

The BACB issued updates in response to the COVID-19 pandemic to allow flexibility with respect to ABA experience/fieldwork requirements through a “compassionate-exception appeals process” (BACB, 2020c). This process allows trainees to make reasonable deviations from requirements, such as those outlining a minimum number of client observations that must be accrued per month. This notice should not be interpreted as a means to free trainees of the requirement to secure client observations, but rather as a means to give them some flexibility in the case that a trainee–client observation could not occur, even with best efforts enacted as trainees adjust.

Another factor to consider is that supervision and coursework requirements will change for exam applicants effective January 1, 2022 (BACB, 2017); thus, trainees everywhere are likely motivated to complete their experience hours following their original schedule (if they are pursuing a BACB 4th Edition Task List verified course sequence; BACB, 2012). Even if trainees could suspend accruing their hours during the pandemic and resume their activities when circumstances allow, this action may prevent them from completing their supervision during an already-tight timeline. Given the convergence of the COVID-19 pandemic and the deadlines imposed on trainees, the current context could deter trainees from their personal and professional goals.

Purpose

Accruing supervision hours through the COVID-19 pandemic presents a challenge for trainees and their supervisors to adapt current supervision activities and focus on some potentially new and different skill sets (e.g., remote parent/caregiver training and coaching, ethically transitioning services), while maintaining an effective competency-based approach.

The purpose of the current article is to support supervisors of trainees pursuing BACB certification in designing effective, ethical approaches to supervision during pandemic-imposed interruptions to service-delivery models. First, we explore barriers that various professionals may face due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and we discuss some potential solutions for maintaining effective supervision and share existing resources available. We then offer three tools to direct supervision planning and trainee involvement in services that could be adopted and adapted for immediate use.

Supervising Trainees in Public School–Based Settings

Globally, localized and country-wide school closures have resulted in up to approximately 1,500,000,000 learners being affected to date (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2020). The majority of the United States mandated school closures through the end of the 2019–2020 school year, and many of these closures have extended into the 2020–2021 school year. Continued disruptions to traditional school services should be anticipated as school-based leaders continue to navigate public health threats.

The unplanned closures of schools to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 create a unique set of challenges for school-based trainees responsible for the delivery of ABA supports and services. Trainees working within the K–12 system may play a number of different roles in the instructional process with varied obligations. Roles for trainees within K–12 educational settings may range from special education or general education teachers, to paraprofessionals, educational specialists, counselors, and consultants. Some professionals seeking BACB certification, particularly special education teachers or consultants, may also be focused on coordinating support and leadership for paraprofessionals. Multidisciplinary teams serving clients may face issues in adapting to maintain consistent collaboration. Because school administrators and other school professionals may not be familiar with the requirements of the BACB, supervisors and trainees may need to provide information about their obligations to follow the BACB Ethics Code in these times of service-delivery-model transitions. As always, depending on the nature of the role of the school-based professional receiving supervision, trainees may need to actively seek out volunteer opportunities that would assist them in covering various required competencies.

Trainees and/or their supervisors face a set of unique circumstances posed by extended school closures and service disruptions. These professionals have the responsibility to consider legal requirements under special education laws (e.g., Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act, 2004), and they must remain aware of and act in accordance with developing or new policies adopted at various levels. School districts are mandated to provide special education and related services as determined through each student’s Individualized Education Program (IEP) amid the pandemic (U.S. Department of Education, 2020). Whereas policies have varied over time, some districts have at times used telepractice approaches exclusively for meeting IEP-related requirements (Capoot & Cicchiello, 2020). Districts in the United States have at times opted to provide in-person special education and related services (including ABA) for students with extensive support needs. Other districts have adopted hybrid models, and many are having caregivers decide among options (Capoot & Cicchiello, 2020).

Supervising Trainees for Insurance-Funded Agencies

Whereas many trainees are currently adapting to gather supervision hours during public school closures or service-delivery model transitions, other trainees, along with their supervisors, working for private agencies to provide insurance-funded ABA services also face challenges during this time. These services are typically delivered in clinics, clients’ homes, community settings, or a combination of these settings. Trainees seeking BACB-required fieldwork supervision through the provision of insurance-funded ABA services are likely to be Registered Behavior Technicians (RBTs). Trainees who are RBTs may have been furloughed or lost their jobs due to the COVID-19 pandemic, threatening both their ability to provide ABA services and their means of acquiring supervised experience.

Insurance plays an important role in funding ABA-based therapy. Some insurance, such as Medicaid (Medicaid.gov, n.d.), allows funding for telepractice ABA services. Other insurance providers may not readily allow remote services (Griswold, n.d.). Restrictions may be placed on the roles of nonlicensed trainees to provide telepractice service (e.g., South Carolina Healthy Connections Medicaid Program, 2020). These restrictions place pressure on agencies to keep costs low and increase caseloads for BCBAs, which consequently could affect their willingness to supervise trainees. Agencies may opt to discontinue supervision programs to save time and effort. However, trainees can play an active role in transitioning from face-to-face to telehealth services with limited disruptions to a child’s treatment, as well as continue to build their own behavior-analytic skills; we explore these possibilities within this article. Given billing restrictions, trainees may find themselves committing to increased levels of voluntary work in order to continue earning experience hours if they are providers of insurance-funded supports.

Common Considerations for Supervisors and Trainees

Unique circumstances and contingencies exist for various settings. Regardless of where services were provided prior to the pandemic, there are many challenges that all supervisors share. The BACB Ethics Code requires behavior analysts to act in the best interest of their clients, prioritizing their care (BACB, 2014, Section 2.0). The BACB issued general ethics guidance on March 20, 2020, for ABA providers during the COVID-19 pandemic (BACB, 2020d). This guidance highlights particularly relevant areas of the BACB Ethics Code, including acting in the interest of clients to maximize therapeutic benefits (Section 2.0), as well as working to eliminate constraints that hinder services and documenting obstacles in eliminating those constraints (section 4.07[b], “Environmental Conditions that Interfere with Implementation”). Supervisors and trainees must abide by laws (BACB, 2014), and they are advised to consider guidelines related to health and safety in order to evaluate risk (e.g., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Risks of stopping, continuing, or augmenting service-delivery models must be considered in tandem with the welfare and desires of clients (LeBlanc et al., 2020). Supervisors and their trainees may find it challenging to arrange effective supervision at this time due to a number of considerations.

Adapting ABA Programs

Policies, guidelines, and resources in response to the COVID-19 pandemic are rapidly changing and being created, and practitioners may feel inundated with new information. The families or caretakers of clients likely also feel this way; therefore, this may be an opportune time to focus on small successes for some trainees and clients to allow them to contact reinforcement (Espinosa et al., 2020). Expectations may need to shift regarding client goals and data collection methods, assessment and intervention selections, and service-delivery modes based on client contexts.

Trainees and supervisors are likely challenged with issues related to collecting data, monitoring progress, and ensuring fidelity of treatment implementation during the pandemic. Client goals may need to shift (both for face-to-face and remote sessions) considering the current needs and preferences of clients and their guardians during the pandemic (Nicolson et al., 2020). For example, in order to practice social distancing, some goals for face-to-face sessions may need to be modified, such as community and social goals. In these instances, supervisors and trainees need to assess to determine what goal modifications are needed (e.g., how to maintain social distance in a store while teaching a client to complete a shopping routine). Therefore, it may be useful for trainees to dedicate time to adapting programs with supervisor support through experience hours. They can participate in team meetings, update or revise objectives and data collection procedures, and take part in designing adapted intervention programs to maximize feasibility when training others, such as parents.

Technology

Technology accessibility, the need for additional training, and other concerns related to arranging effective remote learning environments are potentially major issues (see Baumes et al., 2020, for ethical considerations for delivering ABA sessions remotely). Families and caregivers of clients, supervisors, and trainees alike may have little to no experience with distance education and service-delivery models. To ensure quality supervision, both supervisors and trainees should have appropriate hardware and high-speed internet and be familiar with software in use (Turner et al., 2016). Trainees who previously received no remote supervision may now only be able to accrue supervision of remotely provided services through remote means, presenting challenges that include reduced opportunities to role-play and practice new competencies with clients. Trainees may need to be provided with more access to supervisor-curated resources, such as video models of evidence-supported practices as relevant to client priorities. It is the duty of supervisors and trainees to familiarize themselves with any designated distance technology systems and to obtain training for telepractice ABA service delivery (e.g., Pollard et al., 2017).

Telepractice

Accessing alternatives to school-, outpatient clinic–, or center-based settings should be a top priority, as these areas could be at amplified risk for virus transmission among clients, ABA providers, and other staff. Telepractice/telehealth services, under proper authorizations from the associated insurance providers, can provide a safe alternative, assuming the client is an appropriate candidate for such services. Research reviews exist on telepractice approaches to ABA that can help guide practitioners (Ferguson et al., 2019; Tomlinson et al., 2018).

If only telepractice-based parent training is appropriate, trainees should be specifically taught how to conduct parent training remotely, as procedural fidelity for caregiver training can drop when first implemented via telepractice as compared to in-person training (Lerman et al., 2020). Additionally, it will likely be difficult to update or conduct certain assessments and evaluations via distance technology with clients. Assessment methods may need to incorporate more indirect approaches (e.g., interviews) as a result of site closures.

Rodriguez (2020) presented a selection guide to telepractice services that is tailored to client needs, and it incorporates potential opportunities for behavior technicians to continue direct implementation supports remotely, with or without caregiver assistance. Two recent studies (Ferguson et al., 2020; Pellegrino & DiGennaro Reed, 2020) have demonstrated the effectiveness of direct telepractice interventions. Pellegrino and DiGennaro Reed (2020) had a behavior technician teach two vocal-verbal adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities leisure and vocational skills. Ferguson et al. (2020) implemented discrete-trial teaching with instructive feedback virtually to teach vocal-verbal students with autism spectrum disorder to tact relations. Still, there are indications that many clients would not benefit from direct services delivered virtually. Clients who have difficulty attending or who warrant relatively intrusive prompts and/or frequent reinforcement could best benefit from face-to-face direct services and/or a caregiver-training program (Rodriguez, 2020). That being said, caregivers may also have varied levels of ability to support the ABA program. Trainees and supervisors must keep these client-centered considerations in focus as they consider telepractice methods as an option.

Structuring Adjustments to Supervision

As we discussed, many organizations providing ABA services and supervision have closed their sites due to the pandemic, allowing only remote support for families, clients, and trainees. Some organizations have reopened or created reopening plans to allow flexibility, with the options of distance and traditional face-to-face support (Capoot & Cicchiello, 2020). As a result, school and agency staff are tasked with adopting distance support provision for both clients and trainees. In the event of site closures, trainees must aim to have their supervisor meet client observation requirements at a distance (via live or asynchronous recordings). If this cannot happen after making a reasonable attempt, trainees and their supervisors must explicitly document why, with sufficient detail, in their supervision records (BACB, 2020c).

Fronapfel and Demchak (2020) shared 50 activities in which trainees can engage in order to continue accruing their experience hours and building their skill sets during site closures. This resource serves as a helpful reminder during the pandemic that can be considered with the extant literature on ABA fieldwork supervision. Service delivery and practice are always central to supervised experience. An explicit plan to maintain the integrity and quality of supervision should be implemented with each trainee. There are a variety of supervision guides, supervision literature resources, and competency-based training tools for supervisors and trainees to adopt. Leaders in the area of ABA supervision have published books (e.g., Kazemi et al., 2019; Reid et al., 2012), a special issue in a journal (LeBlanc & Luiselli, 2016), and articles (e.g., Parsons et al., 2012) on competency-based training and supervision practices, including remote supervision (e.g., Britton & Cicoria, 2019; Lerman et al., 2020; Neely et al., 2019; Rispoli & Machalicek, 2020). Supervision guidelines are meant to provide antecedent measures and expectations for supervisors and their trainees (Sellers et al., 2016).

One potentially useful system for trainees and supervisors at this time is the “apprenticeship” model presented by Hartley et al. (2016). In this model, trainees pair up with a supervising BCBA in an apprenticeship role, focusing on unrestricted activities to complete both knowledge-based and performance-based competencies in a format that is mutually beneficial to both the trainee and the organization. With this approach, trainees can learn how to complete risk–benefit analyses for evaluating changes to service delivery or service hours, adapt assessment methods, identify what client skills need to be prioritized, and more. With the apprenticeship model, BCBAs would be best supported in maintaining higher caseloads, clients could continue to receive services, and, ultimately, agencies could continue to earn revenue while also supporting trainees. By providing opportunities for trainees to learn and gain experience in the field while getting financially compensated for their time, they may be more likely to maintain employment with their organization, potentially mitigating the burden of staff turnover. There is also the short-term benefit of having the trainee assist with increased levels of program development needs due to service disruptions, despite potential restrictions to their insurance-billable hours (if applicable). This model is helpful in any case, but such a structure to supervision is especially useful in a time of crisis affecting service delivery. This model for supervision is sustainable through disruptions and can be used with any mode of service delivery.

The restricted service-delivery options imposed by the pandemic may hinder trainees’ abilities to demonstrate competencies. If a trainee does not have the opportunity to demonstrate a competency with a client as planned, the trainee could role-play that practice at a distance with their supervisor until they have an opportunity to practice a targeted skill. Trainees may alternatively be able to record themselves role-playing a target practice with one of their household members, as appropriate. Role-play scenarios and models cannot replace supervised client observations, but opportunities to practice should be provided and documented by the supervisor. Role-play may also help trainees meaningfully participate in training another person, such as a guardian, to engage in a practice.

In one approach, a supervisor could provide a service face-to-face while the trainee joins in at a distance to assist with collecting data, recording interobserver agreement, and/or writing corresponding reports. Conversely, if a trainee is conducting an in-person session while the supervisor observes remotely, feedback could be provided live (e.g., through bug-in-ear technology) or in a delayed manner. In the latter case, the supervisor should record their feedback points and discuss them with the trainee during an individual supervision follow-up meeting as soon as possible. A session, or part of a session, could be recorded and reviewed by the trainee and supervisor, focusing on specific skills to improve. There are some online-interactive and secure (i.e., compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) platforms through which supervisors can provide feedback in a time-stamped manner (e.g., GoReact; Speakworks, Inc., 2020). An alternative or supplemental option from which trainees may benefit is watching videos of themselves and analyzing their own performance using an implementation integrity checklist (Neely et al., 2019). Trainees and supervisors can compare their integrity scores to assess and promote accurate trainee self-evaluation.

The literature and resources for ABA supervision and telepractice are extensive, but the challenges resulting from the pandemic persist and compete with being able to plan for effective supervision. Whereas trainees can still accrue supervision as long as they still have some form of access to clients, it may be difficult for them to prioritize their own development needs during this time without structure tailored to their context. We offer three tools in the following subsections to assist with organizing the ongoing experience of trainees to promote a practical approach that is both client centered and trainee centered.

ABA Fieldwork Plan

Supervisors must consider motivating operations among their trainees as variables at all times. Supervisors should convey appropriate expectations about their requirement to cover the curriculum (i.e., 4th or 5th Edition Task List; BACB, 2012, 2017) as they go about verifying the ongoing experience of each trainee. We recommend applying aspects of a personalized system of instruction (Keller, 1968) to competency-based supervision. Such a system can be in place to track both past and projected activities in the context of a timeline. Projecting out future activities should take place using a goal-setting approach (Garza et al., 2018). Goals should also become more developmentally advanced within various areas over time (Kazemi et al., 2019). Areas covered in the planning process could also center around the trainee’s personal interests or specific persisting needs (e.g., continued focus on graphing data until fluent). This allows for a practical and individualized approach to competency-based supervision for each trainee.

A template for a personalized ABA fieldwork plan is presented in Appendix A. The template allows for incorporating both group “seminar” topics and individual supervision fieldwork activities based around a 15-week term as is typical for many university courses. Existing ABA fieldwork supervision programs (e.g., Britton & Cicoria, 2019; Kazemi et al., 2019) could work with this ABA fieldwork plan—simply write in the names of each activity or development goal to indicate a timeline for completion. We recommend that both the trainee and the supervisor work to set up a plan together. The pair should then conduct regular reviews of the plan, making revisions as needed. Each ABA fieldwork plan is meant to build on prior plans, so we recommend keeping past and present plans together to view and evaluate how experience has accumulated. Such a plan can also work well with portfolios. For instance, one could add a link from an activity title to a permanent product (e.g., assessment report) housed in a portfolio of accumulating project products. There is also a space in the template to note any current potential coursework requirements.

We use this tracking system in our university-based supervision program, as it has the potential benefit of being systematic to support the developmental needs of each trainee. Kazemi et al. (2019) noted potential benefits of university-based supervision, including a systematic focus on trainee development, as well as an enhanced connection to coursework. A personalized ABA fieldwork plan can help trainees make a connection to their coursework for their supervisors, even if they are receiving supervision independent of their university. Aligning any applied activities assigned in coursework to activities delineated in a personalized plan for ABA experience can assist supervisors in reducing response effort emitted by trainees in this time of undue burden. This can also help supervisors understand their trainees’ coursework history and current responsibilities.

Although research is warranted in this area, we find that the ABA fieldwork plan is a practical approach in any context because transitions are inevitable. For instance, trainees will often transfer between supervisors, warranting adequate documentation and communication between supervisors, if possible, to ease the transition process. In the context of the pandemic converging with the BACB Task List transition, such a model may be especially helpful to ensure trainees’ needs are being met over time as client priorities may shift and demand focus.

Client/Family Needs Assessment

Trainees and supervisors must adapt supervision activities to prioritize continuity of care for clients, making every effort to ensure that activities are relevant, valuable, and related to clients. Trainees will likely need to adapt current and future planned activities to work within their individually changing context (e.g., transition to telepractice, parent training). Programmatic changes for clients and activity changes for supervised fieldwork must be communicated to and approved by administrators, clients, and supervisors.

With site closures, parents are being tasked with assisting their children with online instruction. These new responsibilities and changes in schedules can create immense negative impacts for families of recipients of ABA supports (Chung, 2020; Espinosa et al., 2020). It is important for trainees and supervisors to reach out to families, identify barriers to instruction, and help reduce challenges by tailoring their support to best fit the family’s needs. Considering family perspectives will allow practitioners to arrange their services with compassion (Taylor et al., 2018). Trainees should be involved in the process of building their professional skills in addition to their procedural and technical skills. Ongoing assessments of client needs and priorities are helpful to model or suggest for use among ABA fieldwork trainees in all possible natural opportunities. Transitions and conflicts provide real occasions for trainees to practice interpersonal relations with families. Professionalism skills are difficult to program unless trainees are permitted to be in contact with families, such as through directing virtual meetings (e.g., interviews) or being invited to meetings with families to shadow their supervisor. Interruptions in services could call for the design and administration of a needs assessment for clients and their families or care providers, and this is one way trainees might be able to offer support to benefit clients, as well as demonstrate their own professional skills.

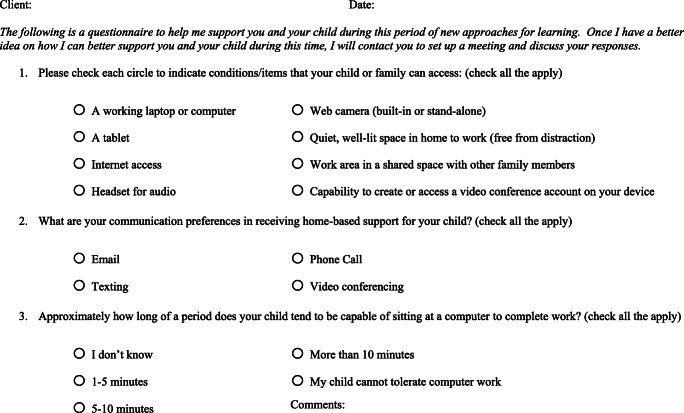

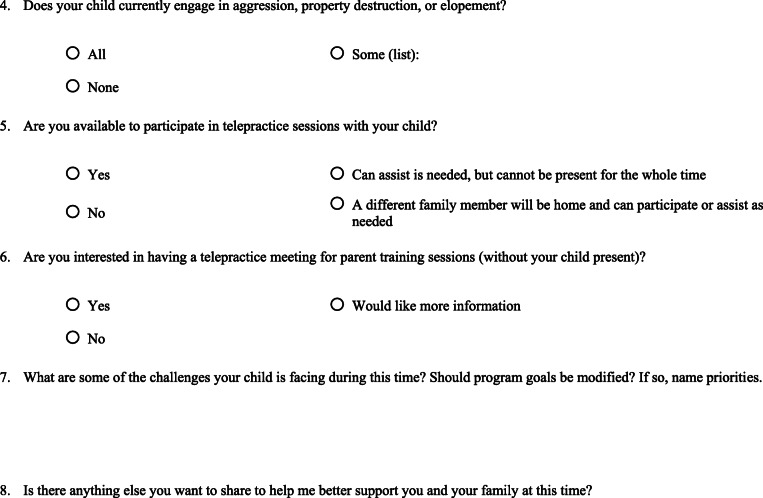

An example of a client/family needs assessment is located in Appendix B. This assessment was developed in consideration of a guide to continuity of care and telepractice during the COVID-19 pandemic published by the Council of Autism Service Providers (2020). An assessment such as this may include open- and close-ended questions that are sent to clients or completed via an interview. This assessment is designed to plan for variables based on client needs, availability, resources, and preferences. For instance, priority goals for a client may change in a new context. Useful skills to practice in one’s home may take a higher priority in a time of school and site closures (e.g., play, communication, daily living skills, self-management). The needs assessment also focuses on environmental barriers (e.g., access to a computer, the internet, and space in the home to work), as well as the prerequisite skills the client needs in order to benefit from online instruction (e.g., social referencing skills, following instructions). Espinosa et al. (2020) developed a risk assessment interview and observation form with some similar features to our assessment to be used to help families arrange a schedule to feasibly support their child in their unique context. The information gathered from a client needs assessment should be reviewed by the trainee, their supervisor, and the family to identify how the client’s program can be adapted as appropriate. A trainee could also work to adapt a form such as this, with supervisor support, to their unique context.

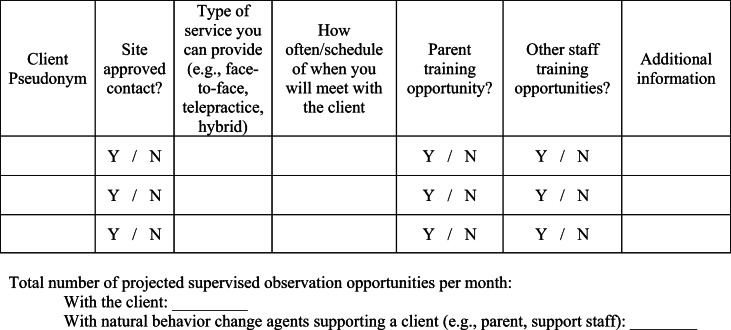

Trainee Needs Assessment

We recommend that supervisors conduct a needs assessment with each of their trainees to identify potential barriers that may impact the trainee’s ability to meet the BACB’s monthly requirements during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results of an ongoing assessment of trainee needs/contexts, along with the client/family needs assessment, can guide supervisors on how to make modifications to fieldwork activities and to ensure trainees are continuing to accrue experience hours through transitions related to the pandemic. The trainee needs assessment should be reviewed frequently and updated as necessary on an individual basis, allowing for quality supervision to continue and to help minimize the loss of learning opportunities during the trainee’s experience. A trainee needs assessment to assist with adapting during the pandemic is located in Appendix C. The assessment here includes sections for the trainee to describe their contexts, including the modes in which they can meet with clients (e.g., face-to-face, telepractice, hybrid), their schedule with each client, and whether there are parent- or caregiver-training opportunities.

Structuring supervision around client needs allows supervision to naturally fit into practice. However, depending on the number of clients trainees serve and their variety of needs, trainees may have a range of levels of flexibility with respect to being able to focus on their own professional development needs. Rules for supervision may not suffice to promote a focus on the needs of trainees while they are under the intense pressures imposed in the context of a global pandemic. Trainees and supervisors are faced with prioritizing client needs while balancing the trainees’ own professional goals. If trainees’ supervision goals are not being met, solutions must be arranged to mitigate this issue.

Summary

As practitioners navigate the unique challenges around the COVID-19 pandemic, it is imperative to ensure the well-being of clients (including families) and trainees by promoting ethical responses to their needs. During a time of uncertainty, supervisors must assess the situation and make data-based decisions in order to commit to providing effective supervision. We discussed some of the unique challenges faced by supervisors and trainees during the COVID-19 pandemic in this article with primary consideration toward professionals based in the United States. We also shared considerations, as well as references and resources, to plan for continuing ethical and effective supervision practices during abrupt interruptions, transitions, and disruptions. Many of the suggestions we have made in this article are applicable to various forms of transitions or interruptions. Transitioning to telepractice is not new, but there is an increase in the use of these services due to the pandemic. The resources shared here are not exhaustive, but during both times of change and usual supervision circumstances, they could be supportive or serve as a refresher for active supervisors and trainees. Investing time in structured, competency-based supervision not only is ethical through the COVID-19 pandemic but also results in both immediate and long-term gains for organizations and the recipients of their services. As we face the next steps in these challenging times, protecting the supervisory relationship during disruptions is essential to maintain integrity in the field of ABA for the benefit of current and future consumers.

Availability of Data and Material

There are no data associated with this study to report.

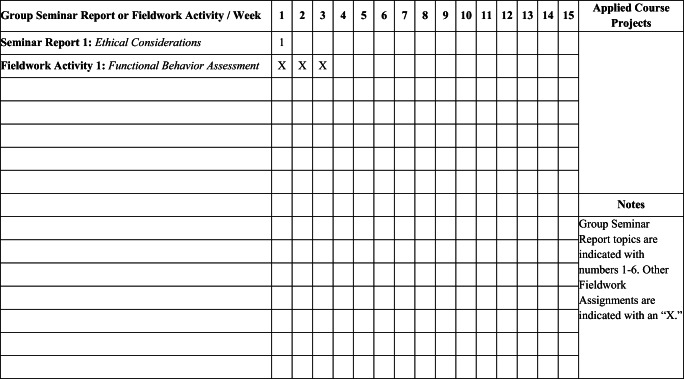

Applied Behavior Analysis Fieldwork Plan

Directions: Place an “X” in the row/column intersection of the week when a specific fieldwork activity will tentatively be completed. Place a cumulative number in the row/column intersection of the week you will tentatively present on a specific topic in group supervision (“seminar report”). Arrange the projected topic/activity order based on your priorities and schedule with the support of and approval from supervisor(s) and administrator(s), adapting as needed to reflect records and ongoing projected activities. Activities may be able to align with applied coursework projects and their respective due dates. This is a culminating document—when the 15-week period has passed, duplicate a blank form for the next period and include previous Applied Behavior Analysis Fieldwork Plans to reference your supervised experience history.

Client/Family Needs Assessment

Trainee Needs Assessment

Trainee name:________________ Date completed by trainee:_______________

Date reviewed with supervisor:_______________

Purpose of Assessment:

The purpose of this assessment is to learn more about how the current restrictions due to COVID-19 will impact your ability to meet the Behavior Analyst Certification Board’s monthly supervision requirements, maintain originally planned hours of experience, and complete originally targeted activities. Your supervisor will review this information with you, along with the result of a needs assessment that was sent out to the families of target clients, to develop a plan to help reduce barriers. There will be ongoing check-ins to monitor new developments and the effectiveness of the plan to address shifts in needs.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Author Note Orchid IDs: Jennifer Ninci https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6527-4297 Marija Čolić https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9700-458X Gregory Taylor https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1225-801X.

We thank Lisha Padilla and Patricia Sheehey for their contributions to the original design of the ABA fieldwork plan, Heather Chapman for her assistance with identifying literature sources, and Billy Wolff for his assistance with formatting.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Asmundson GJG, Taylor S. Coronaphobia: Fear and the 2019-nCoV outbreak. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2020;70:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumes, A., Čolić, M., & Araiba, S. (2020). Comparison of telehealth-related ethics and guidelines and a checklist for ethical decision making in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 13(4), 736–747. 10.1007/s40617-020-00475-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2012). BCBA/BCaBA task list (4th ed.). https://www.bacb.com/bcba-bcaba-task-list/

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2014). Professional and ethical compliance code for behavior analysts. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/BACB-Compliance-Code-english_190318.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2017). BCBA/BCaBA task list (5th ed.). https://www.bacb.com/bcba-bcaba-task-list-5th-ed/

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2019a). BCBA fieldwork requirements. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2022-BCBA-Fieldwork-Requirements_190125.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2019b). BCaBA fieldwork requirements. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2022-BCaBA-Fieldwork-Requirements_190126.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020a). Ethics code for behavior analysts.

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020b). BCBA/BCaBA experience standards: Monthly system.https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/BACB_Experience-Standards_200406-1.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020c). BACB COVID-19 updates. https://www.bacb.com/bacb-covid-19-updates/

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020d). Ethics guidance for ABA providers during COVID-19 pandemic.https://www.bacb.com/ethics-guidance-for-aba-providers-during-covid-19-pandemic-2/

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2021). Crosswalk for behavior analyst ethics codes: Professional and Ethical Compliance Code for Behavior Analysts & Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/ethics-cross-walk-2101015.pdf

- Britton, L. N., & Cicoria, M. J. (2019). Remote fieldwork supervision for BCBA® trainees. Academic Press.

- Capoot, A., & Cicchiello, C. (2020). When will school open? Here’s a state-by-state list. Today. https://www.today.com/parents/when-will-school-open-here-s-state-state-list-t179718

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Implementation of mitigation strategies for communities with local COVID-19 transmission. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/community-mitigation-strategy.pdf

- Chung, W. (2020). COVID-19 and its impact on the SPARK ASD community. SPARK. https://sparkforautism.org/discover_article/covid-19-impact-asd/

- Council of Autism Service Providers. (2020). Practice parameters for telehealth-implementation of applied behavior analysis: Continuity of care during COVID-19 pandemic. https://casproviders.org/practice-parameters-for-telehealth/

- Espinosa, F. D., Metko, A., Raimondi, M., Impenna, M., & Scognamiglio, E. (2020). A model of support for families of children with autism living in the COVID-19 lockdown: Lessons from Italy. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 13(3), 550–558. 10.31234/osf.io/48cme. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, J., Craig, E. A., & Dounavi, K. (2019). Telehealth as a model for providing behaviour analytic interventions to individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(2), 582–616. 10.1007/s10803-018-3724-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, J. L., Majeski, M. J., McEachin, J., Leaf, R., Cihon, J. H., & Leaf, J. B. (2020). Evaluating discrete trial teaching with instructive feedback delivered in a dyad arrangement via telehealth. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 53(4), 1876–1888. 10.1002/jaba.773. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fronapfel, B. H., & Demchak, M. (2020). School’s out for COVID-19: 50 ways BCBA trainees in special education settings can accrue independent fieldwork experience hours during the pandemic. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 13(2), 312–320. 10.31234/osf.io/cr3uv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Garza, K. L., McGee, H. M., Schenk, Y. A., & Wiskirchen, R. R. (2018). Some tools for carrying out a proposed process for supervising experience hours for aspiring Board Certified Behavior Analysts®. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 11(1), 62–70. 10.1007/s40617-017-0186-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Griswold, B. (n.d.). Will insurance cover video and phone sessions? PsychCentral. https://pro.psychcentral.com/will-insurance-cover-video-and-phone-sessions/

- Hartley, B. K., Courtney, W. T., Rosswurm, M., & LaMarca, V. J. (2016). The apprentice: An innovative approach to meet the Behavior Analysis Certification Board’s supervision standards. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(4), 329–338. 10.1007/s40617-016-0136-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Individuals With Disabilities Education Improvement Act, 20 U.S.C. § 1400 (2004).

- Kazemi, E., Rice, B., & Adzhyan, P. (2019). Fieldwork and supervision for behavior analysts: A handbook. Springer Publishing.

- Keller, F. S. (1968). Good-bye, teacher …. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 1(1), 79–89. 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- LeBlanc, L. A., Lazo-Pearson, J. F., Pollard, J. S., & Unumb, L. S. (2020). The role of compassion and ethics in decision making regarding access to applied behavior analysis services during the COVID-19 crisis: A response to Cox, Plavnick, and Brodhead. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 13(3), 604–608. 10.1007/s40617-020-00446-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- LeBlanc, L. A., & Luiselli, J. K. (2016). Refining supervisory practices in the field of behavior analysis: Introduction to the special section on supervision. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(4), 271–273. 10.1007/s40617-016-0156-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lerman, D. C., O’Brien, M. J., Neely, L., Call, N. A., Tsami, L., Schieltz, K. M., Berg, W. K., Graber, J., Huang, P., Kopelman, T., & Cooper-Brown, L. J. (2020). Remote coaching of caregivers via telehealth: Challenges and potential solutions. Journal of Behavioral Education, 29(2), 195–221. 10.1007/s10864-020-09378-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Medicaid.gov. (n.d.). Telemedicine. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/telemed/index.html

- Mertens G, Gerritsen L, Salemink E, Engelhard I. Fear of the coronavirus (COVID-19): Predictors in an online study conducted in March 2020. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2020;74:1–8. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/2p57j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely, L., Rispoli, M., Boles, M., Morin, K., Gregori, E., Ninci, J., & Hagan-Burke, S. (2019). Interventionist acquisition of incidental teaching using pyramidal training via telehealth. Behavior Modification, 43(3), 711–733. 10.1177/0145445518781770. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nicolson, A. C., Lazo-Pearson, J. F., & Shandy, J. (2020). ABA finding its heart during a pandemic: An exploration in social validity. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 13(4), 757–766. 10.1007/s40617-020-00517-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Parsons, M. B., Rollyson, J. H., & Reid, D. H. (2012). Evidence-based staff training: A guide for practitioners. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 5(2), 2–11. 10.1007/BF03391819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pellegrino, A. J., & DiGennaro Reed, F. D. (2020). Using telehealth to teach valued skills to adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 53(3), 1276–1289. 10.1002/jaba.734. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pollard, J. S., Karimi, K. A., & Ficcaglia, M. B. (2017). Ethical considerations in the design and implementation of a telehealth service delivery model. Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice, 17(4), 298–311. 10.1037/bar0000053.

- Reid DH, Parsons MB, Green CW. The supervisor’s guidebook: Evidence-based strategies for promoting work quality and enjoyment among human service staff. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rispoli M, Machalicek W. Advances in telehealth and behavioral assessment and intervention in education: Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2020;29:189–194. doi: 10.1007/s10864-020-09383-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, K. (2020). Maintaining treatment integrity in the face of crisis: A treatment selection model for transitioning direct ABA services to telehealth. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 13(2), 291–298. 10.31234/osf.io/phtgv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sellers, T. P., Alai-Rosales, S., & MacDonald, R. P. F. (2016). Taking full responsibility: The ethics of supervision in behavior analytic practice. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(4), 299–308. 10.1007/s40617-016-0144-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- South Carolina Healthy Connections Medicaid Program. (2020). COVID-19 telehealth policy update to ABA coverage. https://www.scdhhs.gov/press-release/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-temporary-telephonic-and-telehealth-services-updat-4

- Speakworks, Inc. (2020). GoReact [Computer software]. https://get.goreact.com

- Taylor, B. A., LeBlanc, L. A., & Nosik, M. R. (2018). Compassionate care in behavior analytic treatment: Can outcomes be enhanced by attending to relationships with caregivers? Behavior Analysis in Practice, 12(3), 654–666. 10.1007/s40617-018-00289-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tomlinson, S. R. L., Gore, N., & McGill, P. (2018). Training individuals to implement applied behavior analytic procedures via telehealth: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Behavioral Education, 27(2), 172–222. 10.1007/s10864-018-9292-0.

- Turner, L. B., Fischer, A. J., & Luiselli, J. K. (2016). Towards a competency-based, ethical, and socially valid approach to the supervision of applied behavior analytic trainees. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(4), 287–298. 10.1007/s40617-016-0121-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2020). COVID-19 educational disruption and response. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse

- U.S. Department of Education. (2020). Office of Special Education Programs question/answer 20-01. https://www2.ed.gov/policy/speced/guid/idea/memosdcltrs/qa-provision-of-services-idea-part-b-09-28-2020.pdf