Abstract

Objective

The main objective of this study was to assess the prevalence of a minimum acceptable diet (MAD) and associated factors.

Design

Community-based cross-sectional study

Setting

Debre Berhan Town, Ethiopia.

Participants

An aggregate of 531 infants and young children mother/caregiver pairs participated in this study. A one-stage cluster sampling method was used to select study participants and clusters were selected using a lottery method. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all study variables. Statistical analysis was performed on data to determine which variables are associated with MAD and the results of the adjusted OR with 95% CI. P value of <0.05 considered statistically significant.

Primary outcome

Prevalence of MAD and associated factors

Results

The overall prevalence of MAD was 31.6% (95% CI: 27.7 to 35.2). Having mother attending secondary (adjusted OR, AOR=4.9, 95% CI: 1.3 to 18.9) and college education (AOR=6.4, 95% CI: 1.5 to 26.6), paternal primary education (AOR=1.3, 95% CI: 1.5 to 2.4), grouped in the aged group of 12–17 months (AOR=1.8, 95% CI: (1.0 to 3.4) and 18–23 months (AOR=2.2, 95% CI: 1.2 to 3.9), having four antenatal care (ANC) visits (AOR=2.0, 95% CI: 1.0 to 3.9), utilising growth monitoring (AOR=1.8, 95% CI: 1.1 to 2.9), no history of illness 2 weeks before the survey (AOR=2.9, 95% CI: 1.5 to 6.0) and living in the household with home garden (AOR=2.5, 95% CI: 1.5 to 4.3) were positively associated with increase the odds of MAD.

Conclusion

Generally, the result of this study showed that the prevalence of minimum acceptable was very low. Parent educational status, ANC visits, infant and young child feeding advice, child growth monitoring practice, age of a child, a child has no history of illness 2 weeks before the survey, and home gardening practice were the predictors of MAD. Therefore, comprehensive intervention strategies suitable to the local context are required to improve the provision of MAD.

Keywords: nutrition & dietetics, community child health, public health

Strengths and limitation of this study.

This study was conducted at the community level, which increases the probability of generalisability to the entire population that the sample was drawn.

This study used relatively a large sample size using a design effect to increase the power of the study and its generalisability.

This study used a multivariate logistic regression analysis to control all possible confounders.

Seasonal variation, social desirability bias and recall bias were the limitation of the study.

Introduction

Proper nutrition from conception to 24 months of age is a critical window period that determines the survival, health and nutritional status of a child.1 The introduction of appropriate nutrition at age 6 months together with sustaining breastfeeding until 2 years of age warrants optimal growth, development and maintain healthy life throughout the life cycle.2 In contrast, inappropriate infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices lead to stunted growth and poor cognitive development.3

In many resource-limited countries, like Ethiopia, high rate of growth failure occurs within the first 24 months of age and thereafter decreases,4 and this is mainly because of resource limitations and inappropriate child feeding practices.5 Consumption of acceptable dietary standards has numerous benefits; including enhanced linear growth, better cognitive development and high school achievement, reduced risk of non-communicable disease, increased body immunity system and productivity during adult life.1–4 6 7 Meeting a minimum acceptable diet (MAD) is also essential to reduce macronutrient and micronutrient deficiencies that lead to improving linear growth status.8 9 On the other hand, the unmet MAD standard has devastating, long-term and irreversible health outcomes such as stunted growth. Moreover, stunted children become small adults with different adverse health effects in their life course.2 4

The MAD is an IYCF indicator designed to measure appropriate complementary feeding patterns of children aged 6–23 months. It is a composite indicator of the minimum meal frequency (MMF) and minimum dietary diversity (MDD). According to the WHO definition, MAD is the proportion of children aged 6–23 months who had consumed the MMF and MDD during the previous day or night.10 The MDD is used to measure the quality of infant and young child’s complementary diet of child diet, while MMF is used as a proxy measure of energy intake or quantity of food consumed other than breast milk. Furthermore, MAD assesses both micronutrient adequacy and quantity of food consumed during the previous day or night and measures appropriate complementary feeding practices. Similarly, MAD measures multiple dimensions of infant and young child diet; those children aged 6–23 months who meet both macronutrient and micronutrient requirements, but MDD and MMF measure one dimension of infants and young child diets; those infants and young children who meet micronutrients and macronutrient, respectively.9 10

To summarise, assessing MAD is very important for measuring both energy intake and micronutrient adequacy of a child simultaneously than one dimension of diet (diet quality or quantity of diet). However, studies in different areas including Ethiopia showed that consuming the recommended MAD in children aged 6–23 months greatly vary from area to area with the lowest proportion of MAD (8%, 6.7% and 6.1%) being reported in Pakistan, Philippines and Ethiopia, respectively.5 11 12 On the other hand, the highest prevalence of MAD (44.9%, 41.6% and 39.9%) was reported in Indonesia, China and Bangladesh, respectively.13–15

Likewise, in Ethiopia, the proportion of children aged 6–23 months who consume the MAD standard has been reported.12 16 However, the prevalence of MAD in the Ethiopian demographic and health survey was the national average estimate derived from a sample population vary with dietary habits, culture, geographical setting, socioeconomic status, residence, educational status, access to health services and safe drinking water. Besides, the report did not identify all remained potential factors associated with MAD. Furthermore, a study in northwest Ethiopia was conducted among orthodox religious follower mothers during a fasting period indicating that orthodox religious followers limit consummation of animal and animal products. Furthermore, the mother may not prepare a separate dish from animal source food to their children. As a result, these practices may influence the prevalence of MAD in population, geographical location and setting. In contrast, this study was conducted during non-fasting periods and in an urban population with diverse religions, and relatively, it has similar characteristics in child feeding practice, dietary habits, health service, education, water and sanitation service. Macro and micronutrient deficiency are a significant problem in Ethiopia stunting and iron deficiency anaemia remain a burden for infants and young children 6–23 months of age.17 The prevalence of anaemia among children aged 6–23 months reaches 53.7% to 72%,17 18 and the prevalence of stunting is 58%.19

In the Amhara region, child malnutrition is a very severe public health problem with the prevalence of stunting and the infant mortality rate was higher than in other regions in the country. Also, the Amhara region has a low rate of MAD standard and the highest level of child undernutrition has been reported.16 17 19 This maybe because of inappropriate infant and child feeding practices in the first 1000 days. Therefore, determining the prevalence of MAD and identifying factors associated with MAD in the study area has an important role to design cultural, geographical and situation-specific intervention strategies appropriate to the local context. This in turn will help to reduce the burden of child undernutrition and other health problems related to malnutrition in the region including the study area. Therefore, the present study aimed to assess the prevalence of MAD and associated factors among children aged 6–23 months in the Amhara region of Ethiopia.

Methods

Study design, setting, and period

A community-based cross-sectional study design was used from February to March 2018 in Debre Berhan Town, North Shewa, Central Ethiopia. The Town is located 130 km away from Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia. In 2017, the Town has an 88 369 total population, nine kebeles, one referral hospital, three health centres and 14 health posts.

Study participants and sampling technique

All infants and young children 6–23 months with mother/caregiver living in Debre Berhan Town and randomly selected kebeles were considered as the source and study population for this study, respectively. A household considered eligible if the infant and young child aged 6–23 months with mother/caregiver living for at least 6 months in the selected kebeles were included in the study. The child was excluded from the study if the mother/caregiver was absent in the household or the mother/caregiver was unable to respond because of the child’s illness or her illness and if the eligible household was closed after three revisits.

The required sample size for the study was calculated using a single population proportion formula with the following assumptions: the proportion of MAD among infants and young children was 7%,17 a margin of error of 3%, power of 80%, 95% confidence level, design effect of 1.5% and 10% non-response rate. The final required sample size for the study was 459 infants and young children aged 6–23 months with a mother/caregiver. A one-stage cluster sampling method was used to select the study population. The town consists of nine kebeles (the smallest administrative unit in Ethiopia) and kebeles were considered as a cluster to select the study population. Among the nine clusters, three clusters were randomly selected and data were collected from every unit in the selected clusters. The total number of eligible infants and young children aged 6–23 months with their mother/caregiver was taken from the health extension workers (HEWs) record. According to the HEWs record, a total of 577 infants and young children aged 6–23 months—mother pairs were lived in the selected kebeles/clusters. Even though the final calculated sample size required for the study was 459 infants and young children aged 6–23 months pair with mother/caregiver, the total number of 577 infants and young children with mother/caregiver lived in the selected kebeles/clusters. Because of the nature of the cluster sampling method, all eligible (577) infants and young children aged 6–23 months with their mother/caregiver living in the selected clusters were included in the survey.

Data collection methods

Sociodemographic data were collected using pretested and structured interviewer-administered questionnaires developed from prior studies.11 20–22 The study was conducted per the Declaration of Helsinki ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects and each study participant gave informed written consent. The mother/caregiver was interviewed and used as a primary source of data for the study, but if the mother was absent, caregivers were interviewed to collect the data for the study. Ten diploma and two BSc nurses were trained for data collection and supervision, respectively.

Data regarding the household wealth were collected using information from ownerships available assets; ownership of livestock, agricultural land, electronics, radio, television, refrigerator, car, bicycle, cart, gold, sofa, source of water, availability of electricity, type of toilet and household characteristics; type of wall, floor, and ceiling.17

Household food security was measured using Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS), a validated tool developed by Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance. The HFIAS is based on respondent recall in the past 30 days and asks two closely related questions; nine occurrence questions that examine the experience of food insecurity in the past 4 weeks with two response choices as 1=yes or 0=no. Each occurrence questions followed by a frequency of occurrence question that asks the respondent how often the specific condition occurs in the past 4 weeks with the form of Likert scale response as 1=rarely (1–2 times in the past 30 days), 2=sometimes (3–10 times in the past 30 days) and 3=often (>10 times in past 30 days). When summing up the frequency of occurrence questions, the HFIAS score of household range 0–27 and severity of household food insecurity increase with increase the HFIAS score.23

IYCF practices were collected using WHO IYCF standardised questionnaires based on the mother recall of food groups given to her child 24 hours before data collection.10 Finally, all foods that the child consumed were grouped into seven food groups: (1) grains, roots and tubers; (2) legumes and nuts; (3) dairy products; (4) flesh foods; (5) eggs; (6) vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables and (7) other fruits and vegetables.10

Measurements

Food secure household

A household that did not experience any food insecurity conditions or just experience worry, but rarely in the past 4 weeks.23

Food insecure household

A household that experiences one of the three levels of food insecurity conditions; mildly, moderately and severely food insecurity or access conditions in the past 4 weeks categorised as food insecure.23

Minimum dietary diversity

Consumption of four or more food groups from the WHO recommended seven food groups within 24 hours day or night before the survey.10

Minimum meal frequency

The minimum number of times the child consumes solid, semisolid or soft foods (including two milk feeds for non-breastfed children) within 24 hours day or night before the survey. The minimum number of times is two times for breastfed children aged 6–8 months, three times for children aged 9–23 months, and four times for non-breastfeed children 6–23 months of age.10

Minimum acceptable diet

Consumption of the MDD and MMF within 24 hours day or night before the survey.10

Timely introduction of complementary feeding

Providing a child with solid, semisolid or soft foods in addition to breast milk at the age of 6 months.10

Household wealth index

A proxy measure of living standards derived from information on ownership available assets and household characteristics and household classified into terciles category.17

The explanatory variables used for determinant analysis were selected based on similar studies11 15 24 and the following variables were selected to identify factors associated with MAD.

Maternally related variables

Age of mother categorised as: 19–24, 25–29 and ≥30 years of age; educational status of mother: no formal education, primary education, secondary education and college and above; occupational status: housewife, employed, merchant and farmer; mother involvement in deciding on what a child to be feed: involved or not involved; mother has a history of illness within 2 weeks before the survey: yes or no; antenatal care (ANC) visits during pregnancy: less than three ANC visits and four and above ANC visits; maternal fruit and vegetable consumption per week: consume less than three times per week and consume four or more times per week; mother received IYCF advice HEWs: yes or no; mother use child growth monitoring and promotion: yes or no; mother with a history of illness 2 weeks before the survey; and place of delivery: home delivery or health facility delivery.

Father-related variables

Father educational status: have no formal education, primary, secondary and college or above and father occupation: employed, merchant and farmer.

Child-related variables

Child sex: male or female; child age: age 6–11 months, age 12–17 months and age 18–23 months; child initiated to complementary feeding: yes or no; child age at which child introduced with complimentary food: <6 months, at 6 months and after 6 months; child currently bottle feed: yes or no and child has a history of illness with 2 weeks before the survey: yes or no.

Household-related variables

A household wealth index was constructed based on principal component analysis and the household was categorised into terciles: poor, medium and rich; head of household or a person who is responsible for decision-making in a household: father, mother or both; household food security; food secure and food insecure; the presence of home garden: yes or no; and family size: categorised ≤3, 4–5 and ≥6 family members.

MAD was categorised into a dichotomous variable: meeting MAD=1 and not meeting MAD=0. A child who meets both the MDD and MMF was classified as meeting MAD otherwise classified as not meeting MAD.

Quality control

Data collection tools were initially prepared in English and translated into Amharic and then back to English to check for its consistency. A pretest was done on 5% of the study sample, 2 days of training were given for data collectors and supervisors. The principal investigator and supervisors have supervised the data collection process. Data were double-entered for cross-validation.

Statistical analysis

First, data were checked for accuracy and completeness. Then, data were entered into Epi-Data V.3.1 and exported to SPSS V.22 for analysis. A Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology cross-sectional reporting checklist was used.25 Descriptive statistics were used to describe sociodemographic, child feeding practice and maternal and child healthcare unitisation variables. Frequency and percentage were calculated for categorical data and the mean with SD was calculated for continuous variables.

Multicollinearity between explanatory variables was checked with SE; a variable with a SE of ≥2 was dropped from the analysis. To select the appropriate analysis method between cluster-level analysis and ordinary logistic regression for a cluster sampling method, first, we fitted a null model and examined community variation or random effects. The measure of community variation (random-effects) was estimated with intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) and the ICC result was 3%. Since the community variation was less than 5%, the use of an ordinary logistic regression analysis model is sufficient instead of a cluster-level analysis. Bivariable logistic regression analysis was done to assess the association between each covariate with MAD. Covariates with p value<0.25 during bivariable logistic regression analysis; parent education, maternal fruit consumption, head of household, IYCF advice from HEWs, ANC follow-up, growth monitoring utilisation, age of a child, a child has a history of illness 2 weeks before the survey, presence of home garden, household food security and wealth index were included in a multivariable logistic regression model to control all possible confounders and to identify factors significantly associated with MAD. Unadjusted and adjusted ORs with a 95% CI were calculated to estimate the strength association of each explanatory variable with MAD and if the percentage difference between unadjusted and adjusted OR of a variable greater than 10%, a variable considered confounder. Variables with p value<0.05 in the final model were declared statistically significant. A two-factor product term was used to test interaction effects and p value of<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants

Among 577 infants and young children aged 6–23 months living in the selected clusters, 531 mother–children pairs took part in the study making a response rate of 92.0%. Seven infants and young children were excluded according to exclusion criteria and 39 study participants declined to participate in the study. The mean (±SD) age of children was (14.7±5.1) months and the mean (±SD) age of mothers/caregivers was 27 (±4.4) years. Out of the study participants, 500 (94.2%) were married and 467 (87.9%) had formal education (table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the child with a parent in Debre Berhan Town, Ethiopia, February 2018 (n=531)

| Characteristics | Frequency, N (%) |

| Maternal age (in years) | |

| 19–24 | 149 (28.1) |

| 25–29 | 253 (47.6) |

| ≥30 | 129 (24.3) |

| Maternal religion | |

| Orthodox | 505 (95.1) |

| Muslim | 15 (2.8) |

| Other | 11 (2.1) |

| Maternal ethnicity | |

| Amhara | 490 (92.3) |

| Oromo | 37 (7) |

| Other* | 4 (0.7) |

| Maternal level education | |

| Have no formal education | 64 (12) |

| Primary | 137 (25.8) |

| Secondary | 155 (29.2) |

| College and above | 175 (33) |

| Maternal marital status | |

| Single | 19 (3.6) |

| Married | 500 (94.2) |

| Divorced | 7 (1.3) |

| Widowed | 5 (0.9) |

| Maternal occupation | |

| Housewife | 293 (55.2) |

| Merchant | 75 (14.1) |

| Employed | 147 (27.1) |

| Farmer | 16 (3) |

| Husband educational status (n=500) | |

| Have no formal education | 53 (4.4) |

| Primary | 110 (22) |

| Secondary | 162 (32.4) |

| College and above | 206 (41.2) |

| Husband occupation (500) | |

| Employed | 361 (71.6) |

| Merchant | 110 (22) |

| Farmer | 29 (5.8) |

| Family size | |

| ≤3 | 190 (35.8) |

| 4–5 | 273 (51.4) |

| ≥6 | 68 (12.8) |

| Number of under-five | |

| One | 430 (81) |

| ≥Two | 101 (19.2) |

| Child age (in completed months) | |

| 6–11 | 175 (33) |

| 12–17 | 176 (33.1) |

| 18–23 | 180 (33.9) |

| Household wealth index | |

| Poor | 188 (34.4) |

| Medium | 178 (33.5) |

| Rich | 165 (31.1) |

*Other. protestant=10, self beliver=1

Infants and young children feeding practices

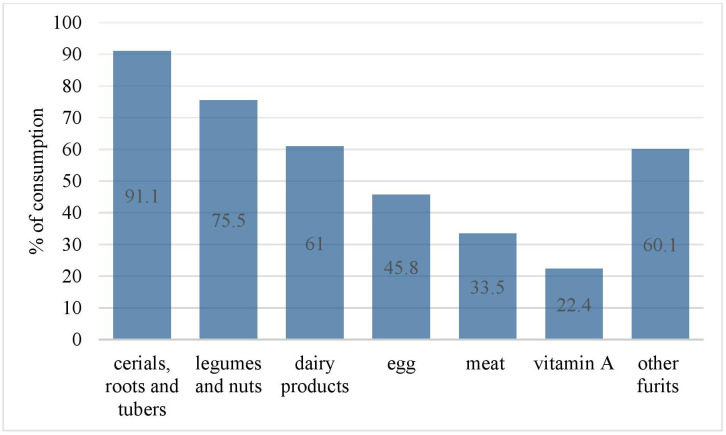

Almost all, 526 (99.1%) children ever breastfeeding, and 482 (91.2%) initiated breastfeeding within 1 hour after birth. Nearly fourth-fifth, 424 (79.8%) children exclusively breastfed up to 6 months and 520 (97.9 %) were introduced to complementary food at 6 months. A majority of 434 (81.7%) were breastfed before the survey. More than half, 290 (54.6 %) children met MMF (table 2). Cereals, roots and tubers were the most consumed food groups (91.1%) and vitamin A was the least (22.4%) consumed food group (figure 1).

Table 2.

Infant and young children feeding practice among children aged 6–23 months in Debre Berhan Town, North Shewa Zone, Amhara Regional State, February 2018

| Variables (n=531) | Frequency, N (%) |

| Ever breastfeed | |

| Yes | 526 (99.1) |

| No | 5 (0.9) |

| Initiation of breastfeeding (n=526) | |

| ≤1 hour | 482 (91.6) |

| ≥1 hours | 44 (8.4) |

| Currently breastfeed (n=526) | |

| Yes | 434 (82.5) |

| No | 92 (17.5) |

| Prelacteal feeding | |

| Yes | 9 (1.7) |

| No | 522 (97.3) |

| Bottle feeding | |

| Yes | 258 (48.6) |

| No | 273 (51.4) |

| Introduction of complementary food | |

| Yes | 520 (97.9) |

| No | 11 (2.1) |

| Age of child complementary food initiated (520) | |

| <6 months | 80 (15.1) |

| At 6 months | 326 (61.4) |

| >6 months | 114 (21.5) |

| Milk feed for non-breastfed children (n=97) | |

| Receive at least two milk feed | 57 (58.8) |

| Not receive two milk feed | 40 (41.2) |

| Meet minimum meal frequency | |

| Yes | 290 (54.6) |

| No | 241 (45.4) |

| Meet minimum dietary diversity | |

| Yes | 235 (44.3) |

| No | 296 (55.7) |

Figure 1.

Food groups consumed by infants and young children aged 6–23 months in Debre Berhan Town, Ethiopia, February 2018.

Maternal and child health service utilisation

The majority, 522 (98.3%) mothers were delivered their child at a health facility, and nearly two-thirds of mothers 350 (65.9%) had four or more ANC during pregnancy. One-quarter of infants and young children 6–23 months of age had a history of illness 2 weeks before the survey (table 3).

Table 3.

Maternal and child health service utilisation in Debre Berhan, Ethiopia, 2018

| Variables | Frequency, N (%) |

| Have focused antenatal care follow-up during pregnancy | |

| Yes | 350 (65.9) |

| No | 181 (34.1) |

| Child growth monitoring service utilisation | |

| Yes | 250 (47.1) |

| No | 281 (52.9) |

| Place of delivery | |

| Health facility | 522 (98.3) |

| Home | 9 (1.7) |

| Postnatal visit | |

| Yes | 205 (38.6) |

| No | 326 (61.4) |

| Family planning use | |

| Yes | 438 (82.5) |

| No | 93 (17.5) |

| Received IYCF advice from HEWs | |

| Yes | 186 (35) |

| No | 345 (65) |

| Maternal history of illness 2 weeks before the survey | |

| Yes | 44 (8.3) |

| No | 487 (91.7) |

| Child history of illness 2 weeks before the survey | |

| Yes | 141 (26.6) |

| No | 390 (73.4) |

HEW, health extension workers; IYCF, infant and young child feeding.

Prevalence of minimum acceptable diet

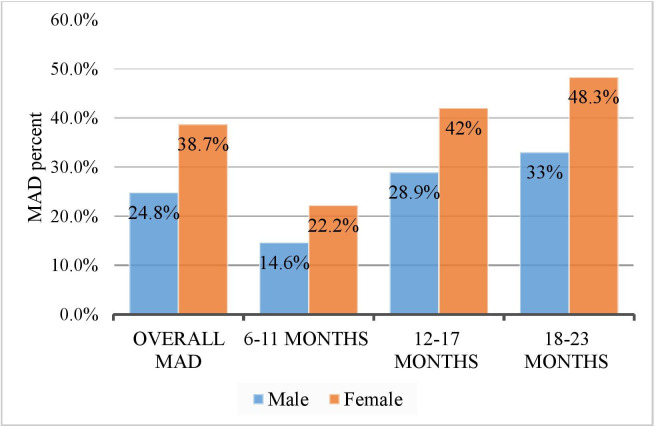

The prevalence of MAD was 31.6% (95% CI: 27.7 to 35.2). The proportion of female children who consumed MAD was higher compared with male children aged 6–23 months and two-fifths (40%) of infant and young children aged 18–23 months consumed MAD (figure 2).

Figure 2.

MAD distribution by sex and age group of infant and young children aged 6–23 months in Debre Berhan Town, Ethiopia 2018. MAD, minimum acceptable diet.

Factors associated with the minimum acceptable diet

After adjustment, mother and father higher level of education, increase child age, home garden practice, a child with no history of illness 2 weeks before the survey, focused ANC visits, participating in growth monitoring and promotion and receiving IYCF advice were positively associated with MAD. Children whose mother attained secondary education had nearly five times (adjusted OR, AOR=4.9, 95% CI: 1.3 to 18.9) and college education were more than six times more likely to receive higher MAD (AOR=6.4, 95% CI: 1.5 to 26.6). While children whose fathers attained primary education had more than three times greater odds of MAD (AOR=1.3, 95% CI: 1.5 to 2.4). Similarly, children who were aged 12–17 were almost two times (AOR=1.8, 95% CI: 1.0 to 3.4), and those who were aged 18–23 months were more than three times had higher odds of MAD compared with children aged 6–11 months. Mothers who attained four ANC visits were two times (AOR=2.0, 95% CI: 1.0 to 3.9) more likely to offer MAD compared with mothers who had less than four ANC contact points. Likewise, mothers who participated in growth monitoring programme were nearly two times (AOR=1.8, 95% CI: 1.1 to 2.9) more likely to provide MAD to their children than. Children who had no history of illness 2 weeks before the survey were nearly three times more likely to get MAD (AOR=2.9, 95% CI: 1.5 to 6.0) than children with a history of illness. Children from the households with a home garden farming had more than two times higher odds of MAD (AOR=2.5, 95% CI: 1.5 to 4.3) (table 4). A two-factor product terms were used to test interaction effects between explanatory variables, but there were no interaction tests found significant.

Table 4.

Factors associated with meeting minimum acceptable diet among children aged 6–23 months in Debre Berhan town, Amhara region, Ethiopia, 2018 (n=531)

| Variables | Meet MAD, N (%) |

Not meet MAD, N (%) |

Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

| Household food security | ||||

| Food secure | 116 (43.4) | 151 (56.6) | 3.13 (2.1 to 4.6) | 1.5 (0.85 to 2.5) |

| Food insecure | 52 (19.7) | 212 (80.3) | Reference | Reference |

| Child growth monitoring utilisation | ||||

| Yes | 102 (40.8) | 148 (59.2) | 2.2 (1.5 to 3.3) | 1.8 (1.1 to 2.9) * |

| No | 66 (23.5) | 215 (76.5) | Reference | Reference |

| Children having history of illness 2 weeks before the study | ||||

| Yes | 16 (11.3) | 125 (88.7) | Reference | Reference |

| No | 152 (39.0) | 238 (61.0) | 4.99 (2.85 to 8.72) | 2.9 (1.5 to 6.0) * |

| Maternal education | ||||

| No formal education | 3 (4.7) | 61 (95.3) | Reference | Reference |

| Primary | 14 (10.2) | 123 (89.8) | 2.31 (0.64 to 8.36) | 0.1 (0.3 to 4.5) |

| Secondary | 60 (38.7) | 95 (61.3) | 12.8 (3.9,42.8) | 4.9 (1.3 to 18.9) * |

| College and above | 91 (52.0) | 84 (48.0) | 22.0 (6.7,72.9) | 6.4 (1.5 to 26.6) * |

| Head of household | ||||

| Father only | 68 (24.6) | 208 (75.4) | Reference | Reference |

| Mother only | 11 (26.2) | 31 (73.8) | 1.08 (0.52,2.3) | 1.3 (0.4 to 4.1) |

| Both father and mother | 89 (41.8) | 124 (59.2) | 2.2 (1.5 to 3.2) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.8) |

| Child age (in completed months) | ||||

| 6–11 | 31 (17.7) | 144 (82.3) | Reference | Reference |

| 12–17 | 64 (36.4) | 112 (63.6) | 2.65 (1.6,4.35) | 1.8 (1.0 to 3.4) * |

| 18–23 | 73 (40.6) | 107 (59.4) | 3.2 (1.9,5.2) | 2.2 (1.2 to 3.9) * |

| Mother fruit consumption per week | ||||

| ≥3 times | 139 (35.9) | 248 (64.1) | 2.2 (1.4 to 3.5) | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.3) |

| <3 times | 29 (20.1) | 115 (79.9) | Reference | Reference |

| The mother receives IYCF counselling from HEW | ||||

| Yes | 84 (45.2) | 102 (54.8) | 2.6 (1.8 to 3.7) | 2.4 (1.4 to 3.9) * |

| No | 84 (24.3) | 261 (75.7) | Reference | Reference |

| Presence of home garden | ||||

| Yes | 48 (44.4) | 60 (55.6) | 3.6 (2.3 to 5.6) | 2.5 (1.5 to 4.3) * |

| No | 108 (25.5) | 315 (74.5) | Reference | Reference |

| Number of ANC visits | ||||

| ≥4 ANC | 147 (42.0) | 203 (58.0) | 5.5 (3.3 to 9.1) | 2.0 (1.0 to 3.9) * |

| ≤3 ANC | 21 (11.6) | 160 (88.4) | Reference | Reference |

| Father level of education | ||||

| No formal education | 8 (15.1) | 45 (84.9) | Reference | Reference |

| Primary education | 33 (30.0) | 77 (70.0) | 2.6 (1.1 to 6.1) | 1.3 (1.5 to 2.4) |

| Secondary education | 39 (24.1) | 123 (65.9) | 1.7 (0.7 to 3.9) | 2.7 (0.7 to 11.1) |

| College and above | 88 (42.7) | 118 (57.3) | 3.98 (1.8 to 8.9) | 2.9 (0.7 to 11.6) |

| Household wealth index | ||||

| Poor | 43 (22.9) | 145 (77.1) | Reference | Reference |

| Medium | 59 (33.1) | 119 (66.9) | 1.7 (1.05,3.6) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.8) |

| Rich | 66 (40.0) | 99 (60.0) | 2.25 (1.4 to 3.6) | 1.1 (0.6 to 2.1) |

*Significant at p value<0.05.

ANC, antenatal care; HEWs, health extension workers; IYCF, infant and young child feeding; MAD, minimum acceptable diet.

Discussion

General findings

The objective of this study was to assess the prevalence of MAD and associated factors among children 6–23 months of age in the Amhara region, central Ethiopia. Our study results showed that the prevalence of MAD among children aged 6–23 months was 31.6%. The study also identified different factors associated with MAD; educational status, number of ANC visits during index child pregnancy, child growth monitoring and promotion utilisation, age of a child, children free of illness 2 weeks before the survey, IYCF advice and home garden were associated with MAD. Children whose parents attained formal education were positively associated with increasing MAD. Children whose mother achieved secondary and college-level education had greater odds of MAD compared with children whose mother had no formal education. Likewise, children whose fathers had primary education were more likely to receive higher odds of MAD than children whose fathers had no formal education. A mother who attained four and above ANC visits and those who participated in child growth monitoring and promotion programmes were more likely to provide MAD to her child. Children aged 12–17 and 18–23 months and those whose mother received IYCF advice from HEWs had greater more odds of MAD compared with children aged 6–11 months and those whose mother did not receive IYCF advice from HEWs. As well, children from households have a home garden farming, and those who had no history of illness 2 weeks before the study had higher odds of MAD. However, the study results should be interpreted with caution because the study was used a cross-sectional study that does not establish a causal relationship and it is conducted during postharvest and prefasting seasons that may be associated with improved child’s consumption of diversified diets from animal and plant food sources.

Comparison with similar studies

Previous studies assessed the prevalence of MAD and associated factors among children aged 6–23 months. In our study, the prevalence of MAD was consistent with the analysis of the Gahanna demographic survey (29.9%) and study from Nepal (33%).26 27 However, the current finding is lower than study reported in Indonesia (44.9%), China (41.6%), India (35.6%–37.7%) and Bangladesh (39.9%).13–15 28 29 In contrast, the prevalence of MAD in the present study greater than studies result in the Philippines (6.7%), Pakistan (8%), Nepal (26.5%), Uganda (23%–26.3%) and Ethiopia (6.1%–7%).5 11 12 17 30 31 The possible reasons for the variation may be due to differences in a study setting, period, population and sample size. Our study identified factors associated with MAD that are consistent with similar studies done across the world. In line with the current study results, a similar study in Indonesia, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Nepal, Ghana and Tanzania established an affirmative association between parental educational status and improved consumption of MAD.13 15 16 26 27 32 Study in Nepal and Philippine showed that the number of ANC visits were positively associated with MAD,5 11 and study in the urban Philippine and Ghana asserted that mother participation in child growth monitoring and promotion associated with improved child’s dietary diversity and frequency of consumption.33 34 Also, study findings from Indonesia, Gahanna, Uganda and Pakistan demographic survey analysis asserted that children who were aged 12–17 and 18–23 months were more likely to have greater odds of MAD.13 27 31 35 A study in the agro-pastoral community of Ethiopia found that the provision of IYCF advice has a positive impact on the child feeding practice.36

Possible mechanisms

Parents who attained formal education significantly increase the odds of MAD. The possible mechanisms between the parents’ higher level of education and improved MAD; an educated parent may have a good understanding about the significance of the recommended IYCF and easily adopt IYCF counselling and education services provided by healthcare providers. Furthermore, higher education achievement has a positive relationship with improved household income and household food security because educated parents may be employed in a better-paid job and this may increase their purchasing power of diversified and high-quality diet to their children. During ANC and child growth monitoring and promotion contact points, the mother/caregiver could receive optimal infants and young children feeding counselling that may increase the odds of MAD. The odds of MAD were higher among children who were aged 12–17 and 18–23 months. The possible reason for the association between greater odds of MAD and increasing age may be due to the mother’s perception of young children’s stomach incompetent to digest solid or semisolid diets. Hence, the mother may introduce only a milk-based diet and start the introduction of diversified solid and semisolid diet after the child age reaches 12 months. Children who were illness-free within 2 weeks before the survey and those who were lived in the household having a home garden had greater odds of MAD. This is because illness reduces child appetite, dietary intake and nutrient absorption lead to lower odds of MAD. On the other hand, home garden farming in resource-limited settings positively associated with improved income, household food security and dietary diversity.37 Thus, children who lived in higher income and food secure households may receive age-appropriate feeding with different food groups. Besides, home garden farming had a positive relationship with increased food availability and accessibility, and mothers may provide their children with a variety of food groups.

Policy implication and future research

The government of Ethiopia launched a revised national nutrition programme (NNP II) to end child malnutrition by the year 2030, and appropriate complementary feeding for children aged 6–23 months is one of the main intervention approaches of NNP II to hunger. However, the current study findings indicated that less than one-third of children aged 6–23 months meet the MAD, and several factors influence the provision of MAD. This denotes that children aged 6–23 months are at higher risk of growth failure, poor mental development and adverse health outcomes. Thus, the government of Ethiopia needs to strengthen existing nutrition programmes and strategies to increase the age-appropriate child feeding practices in the country. Also, the government and other non-governmental organisations need to consider situation-specific nutrition interventions programme to improve the prevalence of MAD. More attention should be given to improve the MAD for uneducated parents, the mother having fewer ANC visits and those who did not participate in growth monitoring and promotion services, child feeding during illness and encourage home garden farming practice. Parental educational status has a positive impact on the MAD. Similar studies affirmed that advanced educational status associated with improved health services utilisation such as ANC and growth monitoring and promotion services utilisation which in turn positively impact the provision of optimum infants and young children feeding practices.33 38 In 2003, the government of Ethiopia launched a health extension programme to provide essential primary healthcare services to all people and begin to deploy community-based health workers called HEWs and study in Ethiopia showed that HEWs have a positive influence on the improvement of maternal and child health service utilisation and health-seeking behaviours.39 40 Ultimately, nutrition information offer during health service utilisation contact points may promote appropriate children feeding practice. Comprehensive nutrition education and counselling and a wide range of health service programmes through community-based health workers, mother-to-mother support groups, religious leaders and idea influencers should be strengthened to improve the provision of MAD in Ethiopia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Haramaya University for giving us this opportunity. Our gratitude also goes to Debre Berhan Town Health Office, Kebeles administrators and Health extension workers for providing the necessary information.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conception and original draft writing: AM. Study design, data analysis and interpretation: AM, GE, AS, BK, MA, LG and AB. Critically review initial draft and finalising manuscript: GE, AS, BK, MA, LG and AB. Preparing manuscript: AM and AS. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Data used to analysis this study are available from corresponding author.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Institutional Health Research Ethics Review Committee (IHRERC) of Haramaya University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences ethically approved the study with reference number C/Ac/R/D/01/878/18 and data were collected after informed written consent taken from study participant.

References

- 1.UNICEF . UNICEF’s approach to scaling up nutrition for mothers and their children, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO . Essential nutrition actions: improving maternal, newborn, infant and young child health and nutrition. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CARE . Infant and young child feeding practices: collecting and using data: a Step-byStep guide. Cooperative for assistance and relief everywhere. Inc CARE, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.USAID . USAID’S infant and young child nutrition project Ethiopia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khanal V, Sauer K, Zhao Y. Determinants of complementary feeding practices among Nepalese children aged 6-23 months: findings from demographic and health survey 2011. BMC Pediatr 2013;13:131. 10.1186/1471-2431-13-131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huffman SL, Schofield D. Consequences of malnutrition in early life and strategies to improve maternal and child diets through targeted fortified products. Matern Child Nutr 2011;7:1–4. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00348.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akombi B, Agho K, Hall J, et al. Stunting, wasting and underweight in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:863. 10.3390/ijerph14080863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones AD, Ickes SB, Smith LE, et al. World Health organization infant and young child feeding indicators and their associations with child anthropometry: a synthesis of recent findings. Matern Child Nutr 2014;10:1–17. 10.1111/mcn.12070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO . Definitions. In: Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices Part 1, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO . Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices Part 2: measurement. World Health Organization, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guirindola MO. Determinants of meeting the minimum acceptable diet among Filipino children aged 6-23 months. Philipp J Sci 2018;147:75–89. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tassew AA, Tekle DY, Belachew AB, et al. Factors affecting feeding 6-23 months age children according to minimum acceptable diet in Ethiopia: a multilevel analysis of the Ethiopian demographic health survey. PLoS One 2019;14:e0203098. 10.1371/journal.pone.0203098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng CS, Dibley MJ, Agho KE. Complementary feeding indicators and determinants of poor feeding practices in Indonesia: a secondary analysis of 2007 demographic and health survey data. Public Health Nutr 2012;15:827–39. 10.1017/S1368980011002485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hipgrave DB, Fu X, Zhou H, et al. Poor complementary feeding practices and high anaemia prevalence among infants and young children in rural central and Western China. Eur J Clin Nutr 2014;68:916–24. 10.1038/ejcn.2014.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kabir I, Khanam M, Agho KE, et al. Determinants of inappropriate complementary feeding practices in infant and young children in Bangladesh: secondary data analysis of demographic health survey 2007. Matern Child Nutr 2012;8:11–27. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00379.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mulat E, Alem G, Woyraw W, et al. Uptake of minimum acceptable diet among children aged 6-23 months in orthodox religion followers during fasting season in rural area, DEMBECHA, north West Ethiopia. BMC Nutr 2019;5:18. 10.1186/s40795-019-0274-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.EDHS . Ethiopia demographic and health survey the DHS program ICF Rockville. Maryland, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roba KT, O'Connor TP, Belachew T, et al. Anemia and undernutrition among children aged 6-23 months in two agroecological zones of rural Ethiopia. Pediatric Health Med Ther 2016;7:131–40. 10.2147/PHMT.S109574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Derso T, Tariku A, Biks GA, et al. Stunting, wasting and associated factors among children aged 6-24 months in Dabat health and demographic surveillance system site: A community based cross-sectional study in Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr 2017;17:96. 10.1186/s12887-017-0848-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dangura D, Gebremedhin S. Dietary diversity and associated factors among children 6-23 months of age in Gorche district, southern Ethiopia: cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr 2017;17:2–7. 10.1186/s12887-016-0764-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchodigni IM, Amoussa Hounkpatin W, Ntandou-Bouzitou G, et al. Complementary feeding practices: determinants of dietary diversity and meal frequency among children aged 6–23 months in Southern Benin. Food Secur 2017;9:1117–30. 10.1007/s12571-017-0722-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wondu GB, Yang N. Determinants of suboptimal complementary feeding practices among children aged 6-23 months in selected urban slums of Oromia zones (Ethiopia). GJNFS 2017;7:1–10. 10.4172/2155-9600.1000593 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coates J. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Food Access. In: Indicator guide: food and nutrition technical assistance, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saaka M, Larbi A, Mutaru S, et al. Magnitude and factors associated with appropriate complementary feeding among children 6–23 months in northern Ghana. BMC Nutr 2016;2. 10.1186/s40795-015-0037-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2007;61. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181577654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gautam KP, Adhikari M, Khatri RB, et al. Determinants of infant and young child feeding practices in Rupandehi, Nepal. BMC Res Notes 2016;9:p. 2–7. 10.1186/s13104-016-1956-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Issaka AI, Agho KE, Burns P, et al. Determinants of inadequate complementary feeding practices among children aged 6–23 months in Ghana. Public Health Nutr 2015;18:669–78. 10.1017/S1368980014000834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmad I, Khalique N, Khalil S, et al. Complementary feeding practices among children aged 6-23 months in Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh. J Family Med Prim Care 2017;6:386–91. 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_281_16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prerna Singhal PS. Status of infant and young child feeding practices with special emphasis on breast feeding in an urban area of Meerut. IOSR-JDMS 2013;7:7–11. 10.9790/0853-0740711 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan GN, Ariff S, Khan U, et al. Determinants of infant and young child feeding practices by mothers in two rural districts of Sindh, Pakistan: a cross-sectional survey. Int Breastfeed J 2017;12:2–8. 10.1186/s13006-017-0131-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mokori A, Schonfeldt H, Hendriks SL. Child factors associated with complementary feeding practices in Uganda. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2017;30:7–14. 10.1080/16070658.2016.1225887 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Victor R, Baines SK, Agho KE, et al. Factors associated with inappropriate complementary feeding practices among children aged 6-23 months in Tanzania. Matern Child Nutr 2014;10:545-61. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2012.00435.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gyampoh S, Otoo GE, Aryeetey RNO. Child feeding knowledge and practices among women participating in growth monitoring and promotion in Accra, Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:1–7. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cabalda AB, Rayco-Solon P, Solon JAA, et al. Home gardening is associated with Filipino preschool children's dietary diversity. J Am Diet Assoc 2011;111:711–5. 10.1016/j.jada.2011.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Na M, Aguayo VM, Arimond M, et al. Risk factors of poor complementary feeding practices in Pakistani children aged 6-23 months: A multilevel analysis of the Demographic and Health Survey 2012-2013. Matern Child Nutr 2017;13:e12463. 10.1111/mcn.12463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liben ML, Abuhay T, Haile Y. Factors associated with dietary diversity among children of agro pastoral households in afar regional state, northeastern Ethiopia. AJPN 2017;5. 10.19080/AJPN.2017.05.555715 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rammohan A, Pritchard B, Dibley M. Home gardens as a predictor of enhanced dietary diversity and food security in rural Myanmar. BMC Public Health 2019;19:1145. 10.1186/s12889-019-7440-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghosh-Jerath S, Devasenapathy N, Singh A, et al. Ante natal care (Anc) utilization, dietary practices and nutritional outcomes in pregnant and recently delivered women in urban slums of Delhi, India: an exploratory cross-sectional study. Reprod Health 2015;12:20. 10.1186/s12978-015-0008-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Medhanyie A, Spigt M, Kifle Y, et al. The role of health extension workers in improving utilization of maternal health services in rural areas in Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:352. 10.1186/1472-6963-12-352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Assefa Y, Gelaw YA, Hill PS, et al. Community health extension program of Ethiopia, 2003-2018: successes and challenges toward universal coverage for primary healthcare services. Global Health 2019;15:24. 10.1186/s12992-019-0470-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Data used to analysis this study are available from corresponding author.