Abstract

Recently, DNA-encoded library (DEL) technology has emerged as an innovative screening modality for the rapid discovery of therapeutic candidates in pharmaceutical settings. This platform enables a cost-effective, time-efficient, and large-scale assembly and interrogation of billions of small organic ligands against a biological target in a single experiment. An outstanding challenge in DEL synthesis is the necessity for water-compatible transformations under ambient conditions. To access uncharted chemical space, the adoption of photoredox catalysis in DELs, including Ni-catalyzed manifolds and radical/polar crossover reactions, has enabled the construction of novel structural scaffolds through regulated odd-electron intermediates. Herein, a critical discussion of the validation of photoredox-mediated alkylation in DEL environments is presented. Current synthetic gaps are highlighted and opportunities for further development are speculated upon.

Sustainable Drug Development

Bridging the gaps between biology and chemistry, small organic compounds remain at the core of discovery research in the pharmaceutical and agrochemical industries [1]. The global pharmaceutical industry invests an estimated US$150 billion annually toward the advancement of safe, effective, and affordable therapeutics to combat human diseases (https://www.ifpma.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/IFPMA-Facts-And-Figures-2017.pdf). Traditionally, high-throughput screening (HTS) [2] and phage display (see Glossary) [3] have played prominent roles in hit identification. These efforts, however, are flawed by their sheer cost and time-intensive labor [2,3]. In recent years, DNA-encoded library (DEL) technology has emerged as an enabling tool in the drug discovery field, featuring an incredibly convenient and rapid way to assess the potential efficacy of billions of chemical compounds (Figure 1) [4–8]. Thus, extremely large libraries can be assembled and screened against a biological target in a single experiment, bypassing the need for special infrastructure. Additionally, DEL platforms afford a time-saving and cost-effective screening format. Compared with the roughly US$2 billion spent on HTS campaigns of millions of compounds contained in extant pharmaceutical libraries, the general cost associated with the assembly and screening of a DEL library of 800 million compounds is about US$150 000 (US$0.0002 per library member) [9].

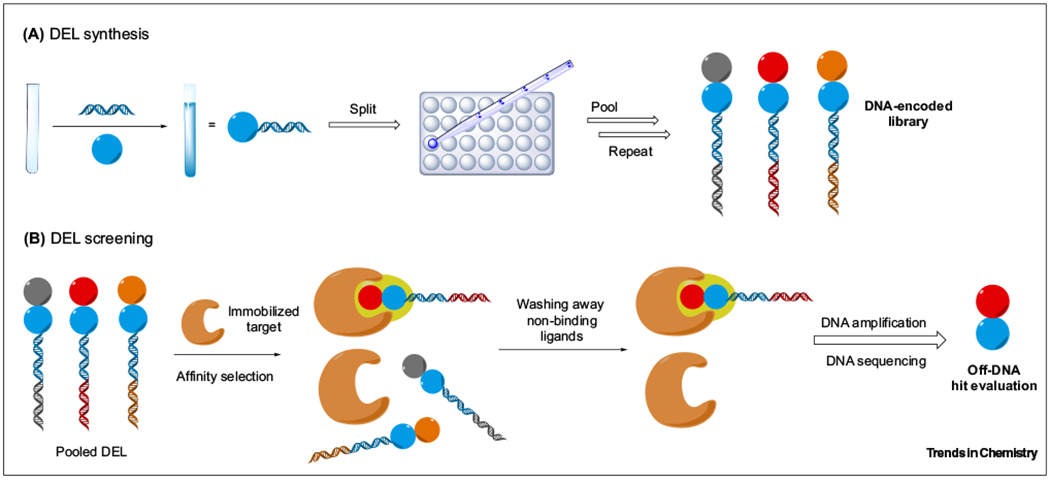

Figure 1. Overview of DNA-Encoded Library (DEL) Technology.

(A) DEL synthesis. (B) DEL screening.

The overall goal in DEL technology is to sample as much chemical space as possible in an effort to increase the probability of hit identification [10–21]. Initially, ‘split-and-pool’ synthesis attaches building blocks to unique DNA barcodes, after which further diversification can occur. Separate reactions are pooled together and then re-arrayed for further building block addition. Multiple cycles of reactions can be carried out consecutively to introduce additional units. Following DEL synthesis, the assembled compounds are incubated with the biomolecular target affixed to a solid support (polymer or resin). Low affinity ligands are washed away, after which the DNA barcode of the remaining high affinity ligands can be PCR-amplified for hit identification by sequencing the DNA ‘barcode’ associated with each small molecule building block. To grow DEL platforms, library members should ideally possess functional handles for derivatization. The presence of DNA, however, imposes restrictions on the types of chemical transformations that are amenable to DEL environments. These constraints include the necessity of mild, aqueous, and dilute conditions. Therefore, robust reaction optimization is crucial to the development of DEL-compatible methods.

To address these limitations, photoredox catalysis has been enlisted to enable a variety of mild on-DNA modifications using photoexcitable catalysts that harness visible light to assemble challenging structural motifs [22]. Traditionally, palladium-catalyzed two-electron cross-couplings with alkyl partners involve harsh reaction conditions and elevated temperatures [23]. Photocatalytic strategies have the potential to revolutionize DEL chemistry, as they are inherently mild, occur mostly at room temperature and without pyrophoric reagents, and the open shell intermediates are able to react productively in aqueous media. This perspective highlights recent milestones in photoinduced alkylation processes in DEL platforms. Herein, a critical overview of the current synthetic challenges is presented and future opportunities for further development in this research arena are discussed.

Emerging DEL Successes

Although DEL technology has been adapted only recently in pharmaceutical settings, it has already given rise to novel drug candidates. In 2016, GlaxoSmithKline employed their 7.7 billion-member DEL platform to identify a potent inhibitor of receptor interacting protein 1 (RIP1) kinase, which plays a prominent role in regulating cell death and inflammation. As a result of this screening, a benzoxazepinone inhibitor (GSK 481) was selected as the lead compound [8]. Another DEL success was reported in 2017 when AstraZeneca, Heptares Therapeutics, and X–Chem recognized the role of protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2) in the treatment of many cancers and inflammatory diseases, and they sought to employ DEL technology to identify a high-affinity inhibitor [24,25]. This led to the identification of AZ3451, a potent and selective allosteric antagonist of PAR2. Additional emerging success stories from academic groups have also been reported recently [26–29].

Ni/Photoredox Dual Catalysis

In the last decade, metallaphotoredox catalysis has emerged as an enabling technology for the construction of challenging C(sp3)-C(sp2) linkages under mild reaction conditions [30–39]. Harnessing a photoexcitable catalyst under visible light, carbon- and heteroatom-based radicals are generated via oxidative or reductive quenching modes through single-electron transfer (SET) and subsequently funneled into a Ni-catalyzed cross-coupling cycle [30–39]. In this vein, Ni/photoredox dual catalysis has enabled late-stage modifications of highly functionalized scaffolds, bypassing the need for elevated temperatures and pyrophoric reagents [40,41]. Owing to the strong correlation between the fraction of C(sp3)-hybridized centers in drug candidates and their enhanced pharmacological profiles (increased solubility and specificity in cellular tissues) [42,43], extensive research efforts have been devoted toward the development of novel reaction paradigms to access uncharted chemical space.

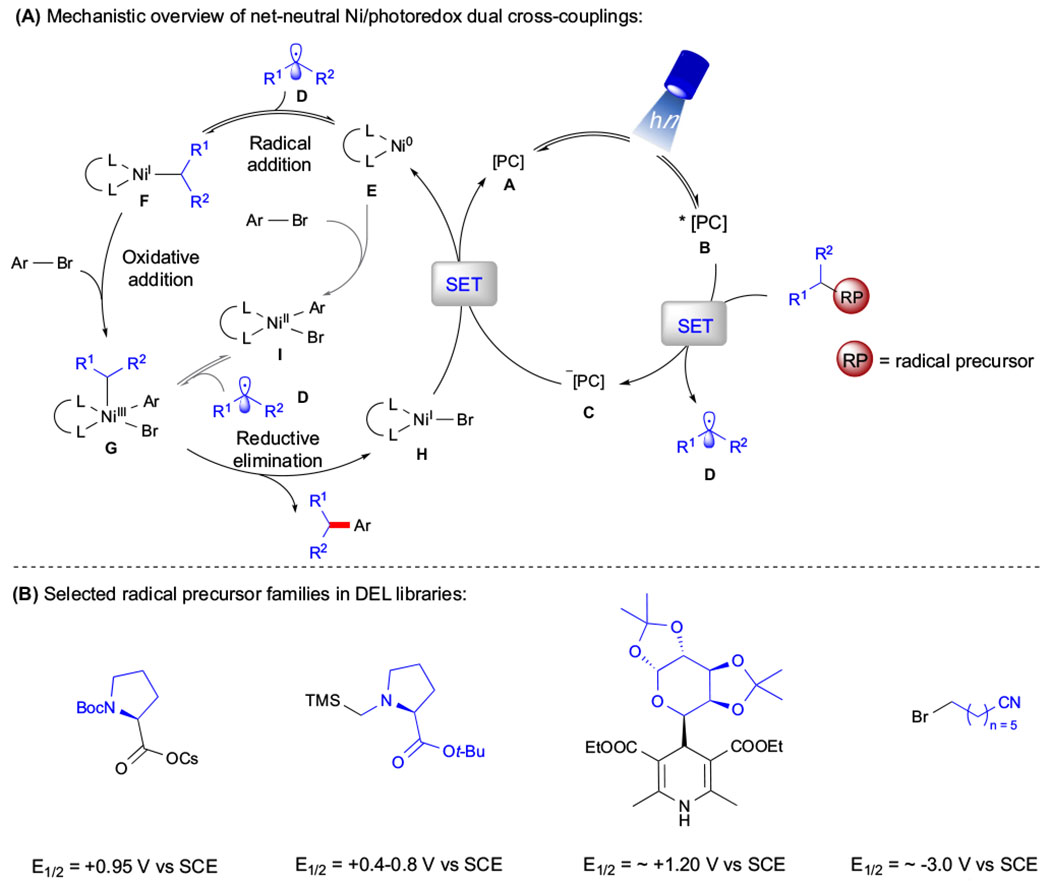

Recently, the adaptation of Ni/photoredox dual manifolds in DEL synthesis has enabled the incorporation of a diverse pool of alkyl feedstocks, including aliphatic carboxylic acids [44–46], α-silylamines [47], alkyl 1,4-dihydropyridines (1,4-DHPs) [44], and aliphatic bromides [47,48] (Figure 2). The success of this integration is owed in large part to the mild nature of photoinduced alkylation pathways, whereby odd-electron intermediates, generated in a regulated fashion, are able to operate under high dilutions (~1 mM) and in the presence of air and water (~20% by volume) [49,50]. Excess reagents are leveraged to induce selectivity in DEL reactions, which are typically carried out on minute scales (~25 nmol).

Figure 2. Overview of Net-Neutral Ni/Photoredox Dual Catalysis.

(A) Mechanistic cycle. The asterisk refers to an ‘excited state’ species. (B) Selected radical precursor families in DEL platforms. Abbreviations: Ar, aryl; Boc, tert-butyloxycarbonyl; Bu, butyl; DEL, DNA-encoded library; Et, ethyl; PC, photocatalyst; RP, radical precursor; SCE, saturated calomel electrode; SET, single electron transfer; TMS, trimethylsilyl.

Mechanistically, net-neutral Ni/photoredox dual systems typically employ a transition metal or organic-based photocatalyst (PC) A that harnesses visible light energy to yield an excited state B, functioning as a strong oxidant (Figure 2). Upon SET with a suitable radical precursor, a high-energy radical species C is generated. This C(sp3)-hybridized intermediate is then intercepted by a low-valent Ni(0) center E, yielding an alkylnickel(I) species F. Oxidative addition with an organic electrophile ensues to yield a high-valent NiIII complex G. Subsequent reductive elimination gives rise to the cross-coupled product and the corresponding NiI-X species H. At this juncture, another SET event from the reduced state of PC C to Ni regenerates both catalysts [51].

In this section, milestones in Ni/photoredox dual cross-couplings in DEL platforms are highlighted.

Carboxylic Acids

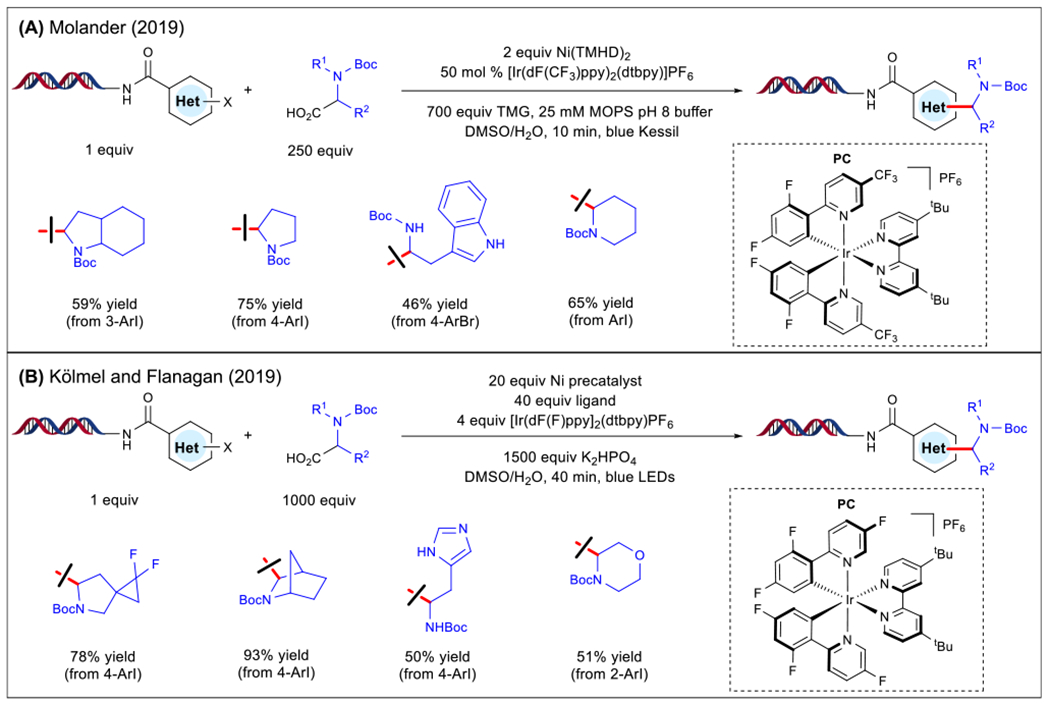

Carboxylic acids are an important class of radical precursors because of their versatile and abundant nature. In particular, these multifunctional building blocks allow an abundance of diversifications in DEL settings. In collaboration with scientists at GlaxoSmithKline, the Molander group devised a cross-coupling protocol of amino acid derivatives with a wide array of DNA-conjugated (het)aryl bromides and -iodides to derive α-heterosubstituted products (Figure 3A) [44]. Remarkably, the reaction can be performed under blue light irradiation within 10 minutes and without the need for inert atmosphere. A large excess of base in the presence of a buffer system [1,1,3,3-tetramethylguanidine (TMG) and 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) pH 8, respectively] led to enhanced reactivity under aqueous conditions. Control experiments (no light, no Ni, no PC) demonstrated that all components were necessary for the reaction to proceed.

Figure 3. On-DNA Ni/Photoredox Decarboxylative Arylation.

(A) Alkylation conditions and scope (Molander [44]). (B) Alkylation conditions and scope (Kölmel et al. [45]). Abbreviations: t-Bu, tert-butyl; Boc, tert-butyloxycarbonyl; dtbpy, 4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyridine; dF(CF3)ppy, 2-(2,4-difluorophenyl)-5-(trifluoromethyl)pyridine; dF(F)ppy, 2-(2,4-difluorophenyl)-5-fluoropyridine; LED, light-emitting diode; MOPS, 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid; PC, photocatalyst; precatalyst ligand, pyridyl carboxamidine scaffold; TMG, 1,1,3,3-tetramethylguanidine; TMHD, 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-3,5-heptanedionate.

With respect to the cross-coupling scope, aryl iodides engaged effectively with complex N-Boc-protected derivatives under the developed conditions. Specifically, aryl systems encompassing tertiary amines and free aniline motifs were tolerated. Unfortunately, diminished reactivity was observed with electron-neutral and electron-rich aryl bromides. The use of more activated heteroaryl bromides proved successful in obtaining pyrrolidine- and indole-containing substrates. Independently, Kölmel, Flanagan, and colleagues at Pfizer demonstrated the merger of photoredox with Ni catalysis in aqueous media in the presence of a Ni precatalyst, employing a pyridyl carboxamidine ligand [45]. Under a similar mechanistic paradigm, cyclic and acyclic α-heterosubstituted products were obtained in excellent yields (Figure 3B). Notably, the use of tertiary N-Boc-protected α-amino acids resulted in decreased yield, presumably because of steric congestion at the Ni center. Other scaffolds encompassing acidic carbamate protons displayed sluggish reactivity under the developed conditions. As a further extension of this water-compatible Ni-catalyzed manifold, the developed reaction conditions were applied to the cross-coupling of an aliphatic bromide, a secondary alkyltrifluoroborate, and an alkyl sulfinate salt. As highlighted, the scope of methods employing carboxylic acid precursors on DNA is largely limited to stabilized radical species (e.g., α-heterosubstituted amino acids). Another inherent limitation is the need for protecting groups for amine functional groups.

Critical to the success of DELs as a platform for ligand discovery in pharmaceutical settings is the integrity of the DNA tag. To probe the potential for radical-based DNA damage, Kölmel, Flanagan, and colleagues conducted DNA ligation experiments followed by qPCR analysis [45]. The DNA tag was determined to be minimally damaged as a result of radical species or blue light irradiation in the absence of oxygen. Importantly, the amount of amplifiable DNA was comparable with a control sample that was not subjected to the metallaphotoredox-catalyzed cross-coupling.

In another report, Novartis researchers reported a catch-and-release strategy using a cationic, amphiphilic polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based polymer to perform Ni/photoredox dual-catalyzed decarboxylative cross-couplings of DNA aryl halides [46]. The scope of this method was extended to nonstabilized primary and secondary radical architectures. However, diminished reactivity was observed with tertiary aliphatic carboxylic acids. With respect to the integrity of the DNA tag under the developed conditions, the authors determined that 48% of amplifiable DNA was recoverable after release from the resin that was used for the photochemical decarboxylative arylation. The corresponding DNA substrate was competent in subsequent elongations.

Silylamines

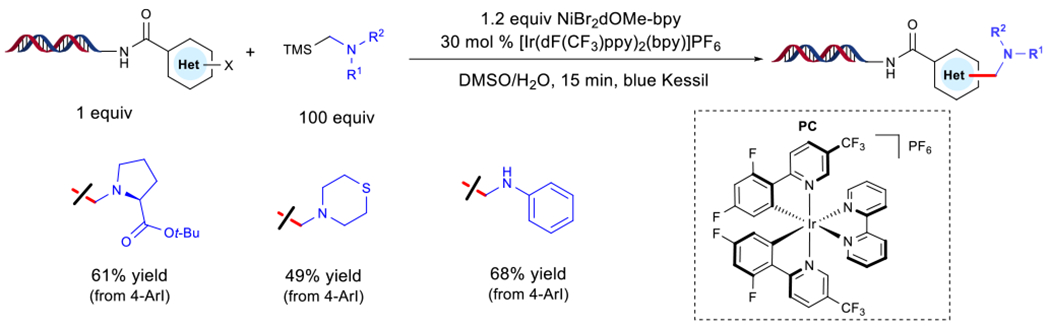

To access free amine functional handles that allow direct derivatization in DEL platforms, the use of organosilanes as radical precursors was investigated because of their favorable redox potentials [E½ = ~ +0.4–0.8 V versus saturated calomel electrode (SCE)] [47,52]. This class of reagents allows the introduction of aminomethyl subunits, a structural motif functioning as a pivotal linker embedded in pharmacologically active molecules. Importantly, silylamines can be readily synthesized by alkylation of diverse, commercially available amines with chloromethyltrimethylsilane. They can also be accessed via reductive amination from commercially available aminomethyltrimethylsilane with assorted ketone and aldehyde feedstocks [47].

Using an iridium (Ir)-based PC under blue light irradiation, effective single-electron oxidation of electron-rich alkyl(trimethyl)silanes can be accomplished to yield silyl radical cations (Figure 4) [47]. Under aqueous conditions, rapid desilylation occurs to yield neutral α-aminomethyl radicals that intercept low-valent Ni species to furnish the desired product. Taking advantage of the low oxidation potentials of this class of reagents, scope elaboration using unprotected aminomethyl derivatives proved successful. Additionally, an organosilane stemming from proline served as a competent substrate with diverse (het)aryl halides, including systems encompassing N-Boc-protected amines, free anilines, and tertiary amines prone to SET oxidation under photoredox conditions [53].

Figure 4. On-DNA Ni/Photoredox Aminomethylation of (Het)aryl Halides.

Abbreviations: bpy, 2,2′-bipyridine; Bu, butyl; dtbpy, 4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyridine; dF(CF3)ppy, 2-(2,4-difluorophenyl)-5-(trifluoromethyl)pyridine; PC, photocatalyst; TMS, trimethylsilyl.

Dihydropyridines

The introduction of 4-alkyl-1,4-dihydropyridines (1,4-DHPs) in photoredox-mediated on-DNA alkylation efforts has expanded the structural feedstocks amenable to DEL libraries. The 1,4-DHPs are readily prepared in a single synthetic step from the corresponding aliphatic aldehydes [54], an abundant class of reagents. The generation of alkyl radicals from 1,4-DHPs via oxidative fragmentation is driven by a re-aromatization event to yield pyridine derivatives [54,55].

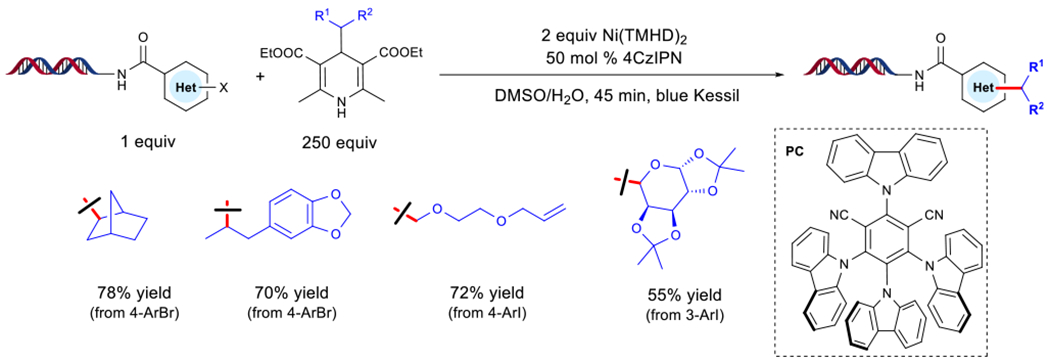

In 2019, the Molander group demonstrated that 1,4-DHPs can be utilized as radical precursors for on-DNA Ni/photoredox cross-couplings with diverse aryl bromides and iodides (Figure 5) [44]. The use of the organic dye 1,2,3,5-tetrakis(carbazol-9-yl)-4,6-dicyanobenzene (4CzIPN) as PC and nickel(II) bis(2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-3,5-heptanedionate) [Ni(TMHD)2] as a user-friendly cross-coupling precatalyst resulted in the formation of the desired C(sp2)-C(sp3) linkage under blue light irradiation. Typically, the major byproduct observed in this reaction stems from a protodehalogenation event of the corresponding aryl halides under aqueous conditions. The use of buffer to modify the pKa of the reaction environment proved unsuccessful. With respect to the versatility of this method, DHPs bearing tertiary, secondary, and stabilized primary substituents showed excellent yields. Of note, reversed C-aryl glycosides were synthesized from saccharide-derived aldehydes. As for the scope of the organic electrophile, electron-neutral aryl bromides showed diminished conversion, while aryl iodides bearing electron-donating functional groups showed high conversion. Unfortunately, unactivated primary alkyl fragments or cyclopropyl motifs did not yield the cross-coupled product because of the high oxidation potentials associated with the instability of the corresponding radical.

Figure 5. On-DNA Ni/Photoredox Alkylation Using 1,4-Dihydropyridines.

Abbreviations: 4CzIPN, 1,2,3,5-tetrakis(carbazol-9-yl)-4,6-dicyanobenzene; Et, ethyl; PC, photocatalyst; TMHD, 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-3,5-heptanedionate.

Alkyl Bromides

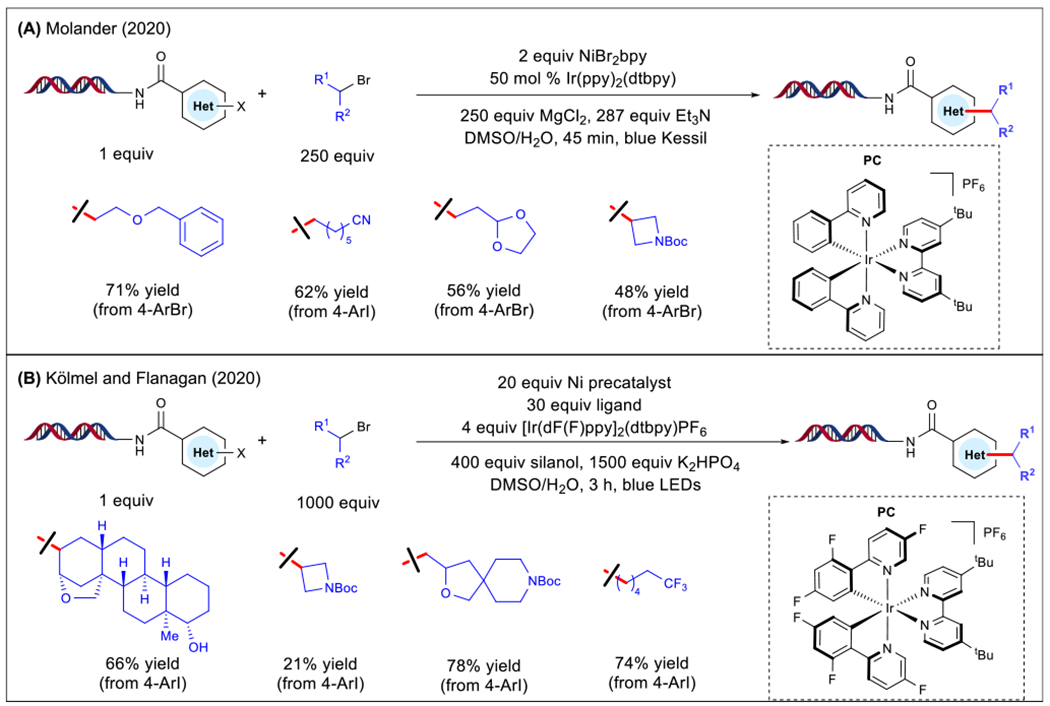

To access unactivated primary radical species, the use of alkyl bromides as commercially abundant feedstocks was examined [47]. These substrates undergo oxidative quenching, thereby necessitating the use of a terminal reductant [56,57]. Traditional cross-electrophile couplings employ a stoichiometric amount of zinc or manganese metal reductants [58]. Inspired by Lei and colleagues [56], Molander and colleagues developed a cross-coupling of aliphatic bromides with on-DNA conjugated aryl halides to furnish the desired C(sp2)-C(sp3) bonds using triethylamine as a mild and benign reductant (Figure 6A) [47]. To enhance selectivity in substrates displaying similar reactivity profiles, a large excess of the radical precursor was leveraged (250 equiv equating to only ~6 μmol of reactants). Of note, enhanced stabilization of the DNA phosphate backbone was achieved using bidentate Mg2+ ions, preventing undesired interactions with iridium. Under these conditions, a wide array of abundant and structurally diverse alkyl bromides was accommodated, with electronically distinct organic electrophiles. Significantly, alkyl bromides featuring bifunctional handles, such as nitriles and free alcohols, were incorporated, allowing further direct derivatization in DEL platforms. Finally, in collaboration with scientists at GlaxoSmithKline, the Molander group evaluated the ability of the arylated products to undergo PCR amplification and sequencing [47]. In contrast to a no-light control reaction, the samples subjected to the photochemical conditions imposed no significant difficulty with respect to ligation, PCR amplification, quantification, or sequencing. These studies highlight the compatibility of photoredox-mediated alkylation with DEL synthesis.

Figure 6. On-DNA Ni/Photoredox Alkylation Using Alkyl Bromides.

(A) Alkylation conditions and scope(Molander[47]). (B) Alkylation conditions and scope(Kölmel et al. [48]). Abbreviations: bpy, 2,2′-bipyridine; t-Bu, tert-Butyl; Boc, tert-butyloxycarbonyl; dtbpy, 4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-pyridine; dF(F)ppy, 2-(2,4-difluorophenyl)-5-fluoropyridine; LED, light-emitting diode; Me, methyl; PC, photocatalyst; ppy, 2-phenyl pyridine.

Shortly after, Kölmel, Flanagan, and colleagues independently devised a net-reductive on-DNA alkylation that proceeds through the intermediacy of a silyl radical intermediate (Figure 6B) [48]. In this transformation, excess inorganic base and silanol reductant [59–61] were employed in conjunction with an Ir-based PC under blue light irradiation. This enabled the installation of spirocyclic amine substrates with high conversion to the alkylated product. Of note, natural product and biologically active scaffolds (a steroid and a pesticide, respectively) were successfully embedded into the cross-coupled product. With respect to DNA-tagged aryl halides, electron-rich and electron-deficient groups were amenable. Notably, sulfonamide and aliphatic cyclopropyl-substituted aryl electrophiles yielded considerable product. To probe DNA compatibility, using an elongated double-stranded DNA substrate (39 base pairs), the authors observed 96% ligation efficiency and 67% PCR amplifiability of the DNA tag upon elimination of residual nickel.

Photoinduced Radical/Polar Crossover Reactions

In recent years, synthetic pathways empowered by photoredox catalysis have allowed rapid access to bioactive subunits [62]. In particular, radical/polar crossover manifolds [63] are attractive for achieving gem-difluoroethylene motifs [64–66]. These scaffolds function as synthetic carbonyl mimics, preserving the electronic and geometric nature of the C=O bond with inherent metabolic stability [67]. In particular, fluorinated motifs are omnipresent in drug candidates as they lead to enhanced binding affinity, cell membrane transport, and cellular specificity [68].

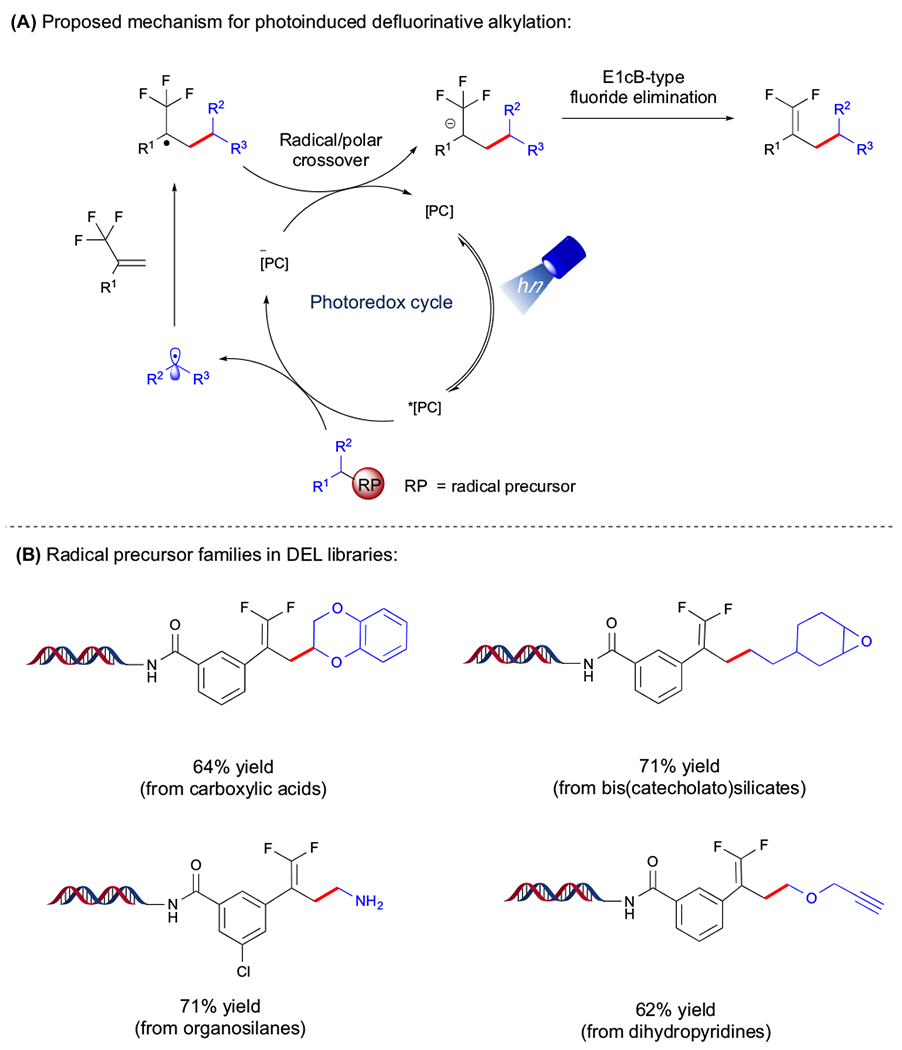

With several commercially available radical precursors and diverse trifluoromethyl-substituted alkenes, unexplored partners were united in a regulated radical defluorinative alkylation to yield medicinally relevant gem-difluoroalkenes. Carboxylic acids [44], silylamines [47], alkylbis (catecholato)silicates [44], and 1,4-DHPs [44] were studied as radical progenitors. Mechanistically, radicals are generated through oxidative fragmentation by the excited state (Figure 7A). A subsequent radical addition occurs with the electron-deficient trifluoromethyl-substituted alkene, yielding an α-CF3 radical. At this juncture, SET reduction of this latter species by the reduced state PC yields a carbanion, which undergoes E1cB-type fluoride elimination to form the desired gem-difluoroalkene. Alternatively, with electron-deficient alkenes, protonation of the α-carbanion occurs to furnish Giese-type adducts [69,70].

Figure 7. Overview of Radical/Polar Crossover Manifolds.

(A) Proposed mechanism for photoredox-mediated defluorinative alkylation. The asterisk refers to ‘excited state’ species, and the minus sign refers to the reduced state of the catalyst. (B) Selected examples of radical precursor families. Abbreviations: t-Bu, tert-butyl; Boc, tert-butyloxycarbonyl; DEL, DNA-encoded library; PC, photocatalyst; RP, radical precursor.

In the following section, photoredox-mediated radical/polar crossover methods using various radical precursor feedstocks in conjunction with on-DNA tethered olefins are discussed (Figure 7B).

Carboxylic Acids

To harness the power of photoredox catalysis for DEL synthesis in other ways, the Molander group demonstrated the use of carboxylic acids as radical precursors to access gem-difluoroalkenes from on-DNA tethered trifluoromethyl-substituted alkenes (Figure 7B) [44]. Given the importance of amino acids as bifunctional handles, their incorporation allows subsequent derivatization in DEL platforms. In the presence of an oxidizing Ir-based PC under blue light irradiation, diverse feedstocks including primary, secondary, and tertiary carboxylic acid derivatives were incorporated. In addition, heterocyclic α-amino acids, including pyridyl, imidazolyl, and benzothienyl groups afforded the desired product in good yields. Of note, Fmoc-protected acids and tertiary derivatives encompassing free alcohol functional groups were accommodated. With respect to the trifluoromethyl-substituted alkene scope, diverse substrates, including chloroaryl- and pyridinyl-substituted alkenes, reacted efficiently.

During the course of reaction optimization, the formation of benzylic trifluoromethyl moieties was observed, resulting from a protonation of the corresponding α-CF3 carbanion under aqueous conditions [44]. Importantly, only trace amounts of this alkane were detected, even in the presence of acidic functional groups. In addition, high loadings of radical precursors resulted in a double addition to the corresponding gem-difluoroalkenes. Therefore, fewer equivalents of radical precursor (5–50 equivalents) were utilized to obtain the desired product selectively.

Independently, Flanagan and colleagues at Pfizer demonstrated a decarboxylative alkylation of α-amino acids in conjunction with DNA-tagged alkenes [70]. Using an inorganic base, effective decarboxylation of the corresponding acid using [Ir{dF(CF3)ppy}2(bpy)] was accomplished in under 6 hours of blue light irradiation. The scope was extended to thioethers and other heterocyclic α-amino acids. With respect to the DNA-tagged radical acceptor scope, α-substituted acrylamides, cyclic α,β-unsaturated ketones, and diverse styrene derivatives were all employed. Subsequently, the Liu group demonstrated a similar photochemical strategy using Fmoc- and Boc-protected α-amino acids in conjunction with α,β-unsaturated ketones [71]. The scope was extended to stabilized α-oxy- and benzylic radical architectures. In a subsequent report, Mendoza and colleagues developed a decarboxylative alkyl coupling using NADH and BuNAH as potent organic photoreductants [72]. Employing electron-poor olefins in conjunction with secondary or tertiary N-hydroxyphthalimide esters (prepared from carboxylic acid feedstocks), the alkylation protocol was carried out under air- and water-compatible conditions. Finally, the decarboxylative coupling of α-amino acids and DNA-conjugated carbonyls was also applied to generate 1,2-amino alcohols [73]. Under the developed conditions and based on qPCR analysis and next-generation sequencing, no DNA damage was detected.

Silylamines

In 2020, Molander and colleagues subjected α-silylamines to radical/polar crossover defluorinative alkylation to induce gem-difluoroalkenes in DEL platforms (Figure 7B) [47]. Of note, the introduction of primary amine functional handles was carried out through the use of commercially available aminomethyltrimethylsilane as a radical precursor. Using ten equivalents of the corresponding organosilanes, effective aminomethylation of the trifluoromethyl-substituted alkene was observed in less than 5 minutes of blue light irradiation. Structurally, a wide array of silylamines was efficiently integrated. Amino acid-based organosilanes also provided excellent yields. Substrates with diverse functional groups, such as glycosides, oxetanes, pyridines, and amides showed effective conversion to products.

Alkylbis(catecholato)silicates

To expand the toolbox of alkyl feedstocks available to DEL chemists, Molander and colleagues further demonstrated the use of alkylbis(catecholato)silicates as radical precursors to access gem-difluoroalkenes under mild reaction conditions (additive-free and near-neutral pH, Figure 7B) [44]. In particular, this class of reagent allows the introduction of unactivated primary alkyl feedstocks as a result of favorable redox potentials [74]. Similarly, upon radical generation using an organic PC variant, primary and secondary alkylbis(catecholato)silicates showed high conversion. Some noteworthy examples included the incorporation of free urea, epoxide, and N-Boc amine scaffolds. Significantly, under higher loadings of the radical precursor, unactivated alkenes remained intact without subsequent addition, providing access to orthogonal reactivity in DEL settings.

Dihydropyridines

Finally, the pool of radical precursors was further extended to include 1,4-DHPs (Figure 7B) [44]. Lower loadings of the 1,4-DHPs, (12.5 equivalents) compared with alkylbis(catecholato)silicates, resulted in full consumption of the corresponding trifluoromethyl-substituted olefin. To demonstrate the versatility of this defluorinative alkylation process, glycosidic moieties and ether functional groups were incorporated. Of note, α-alkoxy motifs demonstrated that stabilized radicals are also compatible. Employing chloroaryl- and pyridinyl-substituted olefins provided good conversions to the desired product.

DNA Compatibility

As highlighted earlier, retaining integrity of the DNA tag during library synthesis enables accurate identification of building blocks and determination of their corresponding binding affinity. In collaboration with scientists at GlaxoSmithKline, the Molander group evaluated the compatibility of the developed photochemical radical/polar crossover reactions in DEL settings [44]. Using three families of radical precursors, a four-cycle tag elongated DNA headpiece was subjected to the defluorinative alkylation conditions. The corresponding samples imposed no significant challenges with respect to PCR amplification and quantitation. Remarkably, there was no disparity with respect to the frequency of misreads between the alkylated products and the control samples (no light and no PC). These findings highlight the power of photoredox manifolds as enabling tools to grow structural complexity in DELs.

Miscellaneous

Photoinduced Cycloaddition Reactions

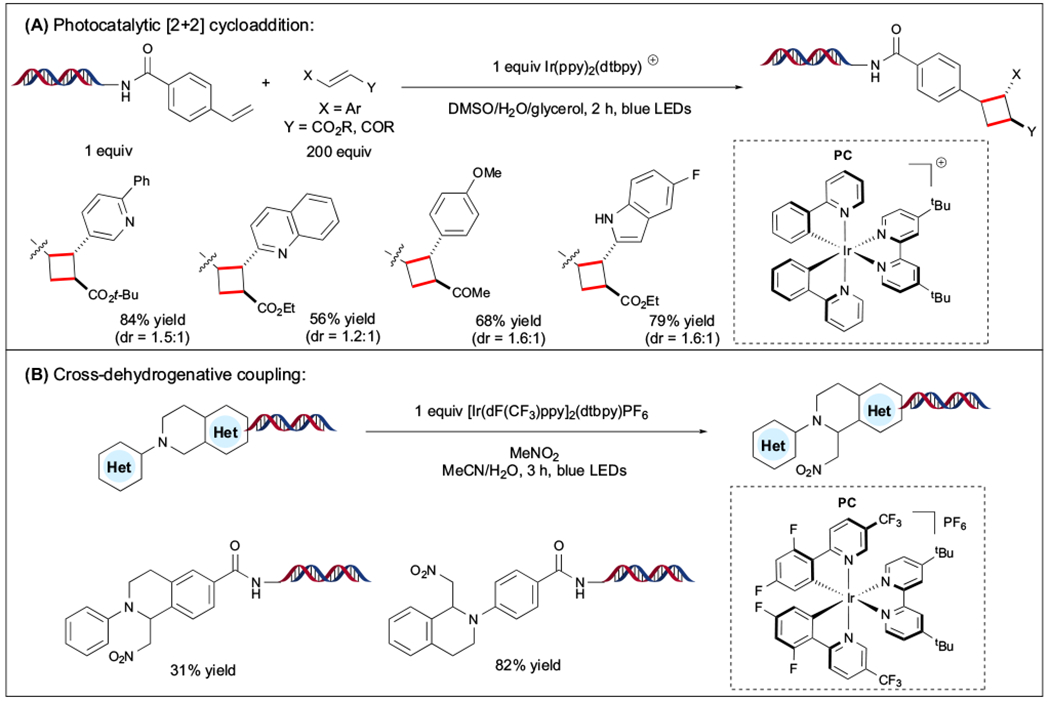

In 2020, Pfizer researchers reported the synthesis of substituted cyclobutanes through a photocatalytic [2 + 2] cycloaddition under aqueous conditions (Figure 8A). In this protocol, DNA-tagged styrene derivatives were reacted with a wide array of cinnamates using a reducing iridium-based PC to assemble two C(sp3)–C(sp3) linkages [75]. Under mild reaction conditions, diverse heteroaromatic systems were tolerated, including pyrazine, pyrrolopyridine, imidazopyrimidine, imidazopyridazine, and pyrazolopyrazine scaffolds. To demonstrate the broad synthetic utility of this method, the cycloaddition products were further functionalized via amide coupling or reductive amination to increase molecular complexity in DEL settings. Finally, to evaluate DNA compatibility, the authors observed 92% ligation efficiency and 60% PCR amplifiability of the DNA elongated tag, highlighting the applicability of this cycloaddition reaction in DEL settings.

Figure 8. On-DNA Photoinduced Transformation.

(A) Photocatalytic [2 + 2] cycloaddition. (B) Cross-dehydrogenative coupling. Abbreviations: Ar, aryl; t-Bu, tert-butyl; dtbpy, 4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-pyridine; Et, ethyl; LED, light-emitting diode; Me, methyl; PC, photocatalyst; Ph, phenyl; ppy, 2-phenyl pyridine.

Cross-Dehydrogenative Coupling

Toward the synthesis of C-1 substituted tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ) structural motifs, the Lu group devised a photoinduced cross-dehydrogenative coupling on DNA (Figure 8B) [76]. Under this paradigm, the oxidation of phenyl-substituted tertiary amine derivatives results in an iminium cation species that is susceptible to nucleophilic addition. Although an array of THIQ scaffolds was tolerated, the scope of the nucleophile coupling partner was limited to nitromethane.

Concluding Remarks

The journey toward innovative drug discovery has overcome a significant challenge with the adaptation of DEL technology in pharmaceutical settings. Immense, uncharted chemical space can now be sampled using a single Eppendorf tube in one experiment, providing a time- and cost-effective format for hit identification. Small-scale, one-pot chemical transformations enable the rapid assembly of DELs with low barriers of implementation. In this vein, high affinity compounds can be pinpointed via PCR amplification and sequencing of the binder’s DNA barcode. After identification, the compound can be synthesized off DNA and subsequently studied for biological activity, promoting further ligand design. Drugs that tackle humanity’s most complicated diseases can be revealed in a drastically shorter time with the wide implementation of DEL technology.

Sampling as many unique chemical motifs as possible increases the probability of hit identification, enabling accelerated drug development. More recently, photoredox catalysis has provided exciting opportunities for unique synthetic disconnections toward biologically relevant molecules. In particular, Ni/photoredox cross-couplings have filled avoid in DELs by increasing the fraction of C(sp3) fragments, which are known to enhance advantageous pharmacological characteristics. In addition, metal-free photoinduced radical/polar crossover pathways, as well as Giese-type additions, have facilitated the synthesis of underexplored motifs, including gem-difluoroalkenes, from on-DNA tagged trifluoromethyl-substituted olefins. Because of the diverse nature of amenable radical precursor families in DELs, photoredox-mediated alkylation enables the introduction of multifunctional subunits that allow rapid derivatization in library settings.

In the near future, more drug discovery efforts are anticipated to exploit DEL synthesis to expand access to new chemical space. However, several challenges persist in DEL technology, with many improvements needed for further development (see Outstanding Questions). These include:

To date, the scope of the radical precursor in Ni/photoredox dual catalytic systems is largely limited to primary and secondary systems because of steric congestion at the metal center. To harness the full power of DELs, the introduction of tertiary alkyl fragments in metallaphotoredox manifolds would allow the construction of quaternary centers that lead to enhanced pharmacological profiles in clinical candidates.

With respect to the scope of the radical acceptor, terminal activated alkenes have been exclusively utilized to bypass sluggish addition rates. To enhance diversity in DEL libraries, the use of highly substituted unsaturated systems, especially unactivated variants, is crucial.

Current synthetic strategies in DELs are largely limited to the assembly of one C–C or C–heteroatom bond. The development of 1,2-difunctionalizations from abundant feedstocks (e.g., alkenes) would expedite the construction of molecular complexity and diversity.

An underexplored realm in DEL synthesis is the incorporation of asymmetric transformations to yield enantiomerically enriched products.

The introduction of novel ligand scaffolds through HTS efforts, coupled with the development of robust analytical tools for on-DNA reactions, remains an outstanding challenge.

Finally, the development of catalytic processes employing emerging base metals, including chromium [77], iron [78], and cobalt [79], presents new avenues for unique reactivity patterns to access unprecedented substructures. With adequate research tools dedicated to this field, DEL technology can be seen to play a pivotal role in future drug discovery efforts.

Outstanding Questions.

Can photoinduced, Ni-catalyzed 1,2-difunctionalizations be harnessed to increase structural complexity in DELs further?

Can ligand design be improved to incorporate tertiary radical intermediates efficiently in metallaphotoredox catalysis?

Can unique reactivity patterns be unlocked by employing base metals in DEL synthesis?

Are photoinduced asymmetric transition metal-catalyzed cross-couplings viable in DEL settings?

Can the scope of commodity chemical feedstocks be expanded for on-DNA reactions?

Can further advantage be taken of charge transfer within electron donor-acceptor complexes in DEL synthesis?

Highlights.

DNA-encoded library (DEL) technology has emerged as an innovative screening modality for exploration of uncharted chemical space in the pharmaceutical industry.

Through single-electron-transfer (SET), odd-electron intermediates are generated in a regulated fashion under mild reaction conditions.

Photoredox-mediated alkylation allows rapid assembly of molecular complexity in DELs while retaining high functional group tolerance.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support provided by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) (R35 GM 131680 to G.M.) and GlaxoSmithKline. S.O.B. is supported by the Bristol-Myers Squibb Graduate Fellowship for Synthetic Organic Chemistry. S.O.B. would like to thank Dr Katelyn Billings and Dr Adam Csakai for their mentorship. We thank Dr Alex Lipp (UPenn) for stimulating discussions. We are immensely grateful to our collaborators at GlaxoSmithKline for their continued support of our research program in this field.

Glossary

- DNA-encoded library (DEL)

diverse compound collections that consist of small molecule building blocks covalently conjugated to DNA sequences that function as molecular barcodes for each embedded building block. This technology allows the rapid identification of ligands with high affinity for biomolecular targets

- Ni/photoredox dual catalysis

a reaction paradigm that generates odd-electron species and funnels these carbon- or heteroatom-based radicals into a Ni-catalyzed cross-coupling cycle for further functionalization. These high-energy intermediates are generated through photoinduced single-electron transfer (SET) events

- Oxidative and reductive quenching modes

SET events, the excited state catalyst initially acts as an oxidant (reductive quenching cycle) or as a reducing agent (oxidative quenching mode). In the overall catalytic cycle, the photocatalyst is converted back to its original resting state by a complementary SET-based oxidation or reduction

- Phage display

this technique was originally described by George P. Smith in 1985 as a method of expressing peptides or proteins as fusions to the coat proteins of a bacteriophage

- Radical/polar crossover manifolds

a photochemically induced process facilitating the generation of radical intermediates that engage in single electron transformations. Subsequently, the radical species created upon initial reaction undergoes a SET event to generate an ionic intermediate

- ‘Split-and-pool’ synthesis

a method that produces combinatorial libraries via repeated cycles, where building blocks are appended and then pooled, followed by splitting for further diversification. In DEL settings, the identity of each building block is encoded via the use of a DNA tag

References

- 1.Stockwell BR (2004) Exploring biology with small organic molecules. Nature 432, 846–854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shelat AA and Guy RK (2007) Scaffold composition and biological relevance of screening libraries. Nat. Chem. Biol 3, 442–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith GP and Petrenko VA (1997) Phage display. Chem. Rev 97, 391–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mannocci L. et al. (2008) High-throughput sequencing allows the identification of binding molecules isolated from DNA-encoded chemical libraries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 105, 17670–17675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buller F. et al. (2008) Design and synthesis of a novel DNA-encoded chemical library using Diels-Alder cycloadditions. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 18, 5926–5931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark MA et al. (2009) Design, synthesis and selection of DNA-encoded small-molecule libraries. Nat. Chem. Biol 5, 647–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Litovchick A. et al. (2015) Encoded library synthesis using chemical ligation and the discovery of sEH inhibitors from a 334-million member library. Sci. Rep 5, 10916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris PA et al. (2016) DNA-encoded library screening identifies benzo[b][1,4]oxazepin-4-ones as highly potent and monoselective receptor interacting protein 1 kinase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem 59, 2163–2178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodnow RA et al. (2017) DNA-encoded chemistry: enabling the deeper sampling of chemical space. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 16, 131–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brenner S and Lerner RA (1992) Encoded combinatorial chemistry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 89, 5381–5383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neri D and Lerner RA (2018) DNA-encoded chemical libraries: a selection system based on endowing organic compounds with amplifiable information. Annu. Rev. Biochem 87, 479–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Usanov DL et al. (2018) Second-generation DNA-templated macrocycle libraries for the discovery of bioactive small molecules. Nat. Chem 10, 704–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gironda-Martínez A. et al. (2019) DNA-compatible diazotransfer reaction in aqueous eedia suitable for DNA-encoded chemical library synthesis. Org. Lett 21, 9555–9558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ottl J. et al. (2019) Encoded library technologies as integrated lead finding platforms for drug discovery. Molecules 24, 1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flood DT et al. (2020) DNA encoded libraries: a visitor’s guide. Isr. J. Chem 60, 268–280 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Götte K. et al. (2020) Reaction development for DNA-encoded library technology: from evolution to revolution? Tetrahedron Lett. 61, 151889 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Catalano M. et al. (2020) Selective fragments for the CREBBP bromodomain identified from an encoded self-assembly chemical library. ChemMedChem 15,1752–1756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song M and Hwang GT (2020) DNA-encoded library screening as core platform technology in drug discovery: its synthetic method development and applications in DEL synthesis. J. Med. Chem 63, 6578–6599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westphal MV et al. (2020) Water-compatible cycloadditions of oligonucleotide-conjugated strained allenes for DNA-encoded library synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 142, 7776–7782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madsen D. et al. (2020) An overview of DNA-encoded libraries: a versatile tool for drug discovery. Prog. Med. Chem 59, 181–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerry CJ and Schreiber SL (2020) Recent achievements and current trajectories of diversity-oriented synthesis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 56, 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li P. et al. (2020) Visible-light photocatalysis as an enabling technology for drug discovery: a paradigm shift for chemical reactivity. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 11, 2120–2130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doucet H. (2008) Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reactions of alkylboronic acid derivatives or alkyltrifluoroborates with aryl, alkenyl or alkyl halides and triflates. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2008, 2013–2030 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng RKY et al. (2017) Structural insight into allosteric modulation of protease-activated receptor 2. Nature 545, 112–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang X. et al. (2019) Protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR-2) antagonist AZ3451 as a novel therapeutic agent for osteoarthritis. Aging (Albany NY) 11,12532–12545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maianti JP et al. (2014) Anti-diabetic activity of insulin-degrading enzyme inhibitors mediated by multiple hormones. Nature 511,94–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buller F. et al. (2011) Selection of carbonic anhydrase IX inhibitors from one million DNA-encoded compounds. ACS Chem. Bio 6, 336–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samain F. et al. (2015) Tankyrase 1 inhibitors with drug-like properties identified by screening a DNA-encoded chemical library. J. Med. Chem 58, 5143–5149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leimbacher M. et al. (2012) Discovery of small-molecule interleukin-2 inhibitors from a DNA-encoded chemical library. Chem. Eur. J 18, 7729–7737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tellis JC et al. (2014) Dual catalysis. Single-electron transmetalation in organoboron cross-coupling by photoredox/nickel dual catalysis. Science 345, 433–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zuo Z. et al. (2014) Merging photoredox with nickel catalysis: coupling of a-carboxyl sp3-carbons with aryl halides. Science 345, 437–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Primer DN et al. (2015) Single-electron transmetalation: an enabling technology for secondary alkylboron cross-coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 2195–2198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shields BJ and Doyle AG (2016) Direct C(sp3)-H cross coupling enabled by catalytic generation of chlorine radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc 138, 12719–12722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heitz DR et al. (2016) Photochemical nickel-catalyzed C-H arylation: synthetic scope and mechanistic investigations. J. Am. Chem. Soc 138, 12715–12718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tellis JC et al. (2016) Single-electron transmetalation via photoredox/nickel dual catalysis: unlocking a new paradigm for sp3-sp2 cross-coupling. Acc. Chem. Res 49, 1429–1439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsui JK et al. (2017) Photoredox-mediated routes to radicals: the value of catalytic radical generation in synthetic methods development. ACS Catal. 7, 2563–2575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Milligan JA et al. (2019) Alkyl carbon-carbon bond formation by nickel/photoredox cross-coupling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 58, 6152–6163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Badir SO and Molander GA (2020) Developments in photoredox/nickel dual-catalyzed 1,2-difunctionalizations. Chem 6, 1327–1339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lipp A. et al. (2020) Stereoinduction in metallaphotoredox catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 59, 2–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vara BA et al. (2018) Scalable thioarylation of unprotected peptides and biomolecules under Ni/photoredox catalysis. Chem. Sci 9, 336–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bloom S. et al. (2018) Decarboxylative alkylation for site-selective bioconjugation of native proteins via oxidation potentials. Nat. Chem 10, 205–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brown DG and Bostrom J. (2016) Analysis of past and present synthetic methodologies on medicinal chemistry: where have all the new reactions gone? J. Med. Chem 59, 4443–4458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneider N. et al. (2016) Big data from pharmaceutical patents: a computational analysis of medicinal chemists’ bread and butter. J. Med. Chem 59, 4385–4402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Phelan JP et al. (2019) Open-air alkylation reactions in photoredox-catalyzed DNA-encoded library synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 141, 3723–3732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kölmel DK et al. (2019) On-DNA decarboxylative arylation: merging photoredox with nickel catalysis in water. ACS Comb. Sci 21, 588–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruff Y. et al. (2020) An amphiphilic polymer-supported strategy enables chemical transformations under anhydrous conditions for DNA-encoded library synthesis. ACS Comb. Sci 22, 120–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Badir SO et al. (2020) Multifunctional building blocks compatible with photoredox-mediated alkylation for DNA-encoded library synthesis. Org. Lett 22, 1046–1051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kölmel DK et al. (2020) Photoredox cross-electrophile coupling in DNA-encoded chemistry. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 533, 201–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malone ML and Paegel BM (2016) What is a “DNA-compatible” reaction? ACS Comb. Sci 18,182–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matsui JK et al. (2017) Metal-free C-H alkylation of heteroarenes with alkyltrifluoroborates: a general protocol for 1°, 2° and 3° alkylation. Chem. Sci 8, 3512–3522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gutierrez O. et al. . (2015) Nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling of photoredox-generated radicals: uncovering a general manifold for stereoconvergence in nickel-catalyzed cross-couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 4896–4899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Remeur C. et al. (2017) Aminomethylation of aryl halides using alpha-silylamines enabled by Ni/photoredox dual catalysis. ACS Catal. 7, 6065–6069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yi J. et al. (2019) Deaminative reductive arylation enabled by nickel/photoredox dual catalysis. Org. Lett 21, 3346–3351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nakajima K. et al. (2016) Visible-light-mediated aromatic substitution reactions of cyanoarenes with 4-alkyl-1,4-dihydropyridines through double carbon-carbon bond cleavage. ChemCatChem 8,1028–1032 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gutierrez-Bonet Á. et al. (2016) 1,4-Dihydropyridines as alkyl radical precursors: Introducing the aldehyde feedstock to nickel/Photoredox dual catalysis. ACS Catal. 6, 8004–8008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Duan Z. et al. (2016) Nickel-catalyzed reductive cross-coupling of aryl bromides with alkyl bromides: Et3N as the terminal reductant. Org. Lett 18, 4012–4015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu W. et al. (2019) Dual nickel- and photoredox-catalyzed reductive cross-coupling of aryl vinyl halides and unactivated tertiary alkyl bromides. Chem. Commun 55, 5918–5921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Everson DA and Weix DJ (2014) Cross-electrophile coupling: principles of reactivity and selectivity. J. Org. Chem 79, 4793–4798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang P. et al. (2016) Silyl radical activation of alkyl halides in metallaphotoredox catalysis: a unique pathway for cross-electrophile coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc 138, 8084–8087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Le C. et al. (2018) A radical approach to the copper oxidative addition problem: trifluoromethylation of bromoarenes. Science 360, 1010–1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sakai HA et al. (2020) Cross-electrophile coupling of unactivated alkyl chlorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 142, 11691–11697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Badir SO et al. (2018) Synthesis of reversed C-acyl glycosides through Ni/photoredoxdual catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 57, 6610–6613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wiles RJ and Molander GA (2020) Photoredox-mediated net-neutral radical/polar crossover reactions. Isr. J. Chem 60, 281–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xiao T. et al. (2016) Synthesis of functionalized gem-difluoroalkenes via a photocatalytic decarboxylative/defluorinative reaction. J. Org. Chem 81, 7908–7916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lang SB et al. (2017) Photoredox generation of carbon-centered radicals enables the construction of 1,1-difluoroalkene carbonyl mimics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 56, 15073–15077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wiles RJ et al. (2019) Metal-free defluorinative arylation of trifluoromethyl alkenes via photoredox catalysis. Chem. Commun 55, 7599–7602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Magueur G. et al. (2006) Fluoro-artemisinins: when a gem-difluoroethylene replaces a carbonyl group. J. Fluor. Chem 127, 637–642 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Meanwell NA (2011) Synopsis of some recent tactical application of bioisosteres in drug design. J. Med. Chem 54, 2529–2591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Millet A. et al. (2016) Visible-light photoredox-catalyzed Giese reaction: decarboxylative addition of amino acid derived alpha-amino radicals to electron-deficient olefins. Chemistry 22, 13464–13468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kolmel DK et al. (2018) Employing photoredox catalysis for DNA-encoded chemistry: decarboxylative alkylation of alpha-amino acids. ChemMedChem 13, 2159–2165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu R. et al. (2020) Exploring aldol reactions on DNA and applications to produce diverse structures: an example of expanding chemical space of DNA-encoded compounds by diversity-oriented synthesis. Chem. Asian J Published online October 29, 2020. 10.1002/asia.202001105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chowdhury R. et al. (2020) Decarboxylative alkyl coupling promoted by NADH and blue light. J. Am. Chem. Soc 142, 20143–20151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wen H. et al. (2020) Synthesis of 1,2-amino alcohols by photoredox-mediated decarboxylative coupling of alpha-amino acids and DNA-conjugated carbonyls. Org. Lett Published online November 10, 2020. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c03461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jouffroy M. et al. (2016) Base-free photoredox/nickel dual-catalytic cross-coupling of ammonium alkylsilicates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 138, 475–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kolmel DK et al. (2020) Photocatalytic [2 + 2] cycloaddition in DNA-encoded chemistry. Org. Lett 22, 2908–2913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wen X. et al. (2020) On-DNA cross-dehydrogenative coupling reaction toward the synthesis of focused DNA-encoded tetrahydroisoquinoline libraries. Org. Lett 22, 5721–5725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schwarz JL et al. (2020) 1,2-Amino alcohols via Cr/photoredox dual-catalyzed addition of alpha-amino carbanion equivalents to carbonyls. J. Am. Chem. Soc 142, 2168–2174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ouyang X-H et al. (2019) Intermolecular dialkylation of alkenes with two distinct C(sp3) -H bonds enabled by synergistic photoredox catalysis and iron catalysis. Sci. Adv 5, eaav9839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thullen SM and Rovis T. (2017) A mild hydroaminoalkylation of conjugated dienes using a unified cobalt and photoredox catalytic system. J. Am. Chem. Soc 139, 15504–15508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]