Abstract

Objective:

To synthesize published findings on the relationship between early life adversity and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) cortisol parameters in pregnant women.

Data sources:

We searched PubMed, CINAHL, and PsychINFO databases using variants and combinations of the keywords early life adversity, pregnancy, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and cortisol.

Study selection:

We selected articles that included pregnant participants, included measures of both cortisol and early life adversity, were published in English in a peer-reviewed journal, and were of sufficient methodological quality. Date of publication was unrestricted through May 2020.

Data extraction:

Twenty-five articles met the inclusion criteria and were evaluated for quality and risk of bias. Sources of cortisol included saliva, hair, plasma, and amniotic fluid.

Data synthesis:

We categorized findings according to four physiologically distinct cortisol output parameters: diurnal (daily pattern), phasic (in response to an acute stressor), tonic (baseline level) and pregnancy-related change. Preliminary evidence suggests that early adversity may be associated with elevated cortisol awakening response (diurnal) and blunted response to acute stressors (phasic), irrespective of other psychosocial symptoms or current stress. For women with high levels of current stress or psychological symptoms, early adversity was associated with higher baseline (tonic) cortisol levels.

Conclusion:

Early life adversity in women is linked with alterations in cortisol regulation that are apparent during pregnancy. Researchers should examine how variations in each cortisol parameter differentially predict pregnancy health risk behaviors, maternal mental health, and neonatal health outcomes.

Keywords: Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, neuroendocrine, prenatal, adverse childhood experiences, abuse, trauma, toxic stress

Precis

Early life adversity in women was associated with physiologic cortisol alterations that are evident during pregnancy.

Early life adversity has lasting and widespread effects on overall health, functioning, and well-being over the life course (Cowan et al., 2016; Felitti et al., 1998). In pregnant women, early life adversity is associated with numerous mental, physical, and reproductive health outcomes (Olsen, 2018). Women exposed to early life adversity are more likely to have shorter pregnancies, experience preterm birth, and have low birth weight infants (Cammack et al., 2011; Christiaens et al., 2015; Selk et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2016). Early life adversity is also significantly associated with a wide variety of increased psychosocial and behavioral health risks in pregnant women, including smoking, alcohol and substance misuse, teenage pregnancy, and risky sexual practices that place pregnant women at risk for genitourinary infections (Blalock et al., 2011; Negriff et al., 2015; Olsen, 2018; Winn et al., 2003). In addition, early adversity and abuse in women is associated with perinatal depression (Records & Rice, 2005), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety disorders, and suicide (Dube et al., 2001; Heim et al., 2010; Kendler & Aggen, 2014; Weiss et al., 2016). These relationships are apparent even after controlling for women’s sociodemographic characteristics and history of psychopathology (Choi & Sikkema, 2016).

Early life adversity is a broad category of experiences that occur from birth through adolescence, including maltreatment, neglect, abuse, trauma, violence, chronic stress, social disadvantage, and poverty. Childhood is an especially susceptible time for neural programming by environmental influences. These programming effects are particularly evident in neural circuits underlying perception of threat, reward, and executive control (Nusslock & Miller, 2016). Increased perception of threat, mediated in part by hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis functioning in relation to stress, may help to explain why some women with a history of early life adversity experience higher rates of psychological disorders in adulthood, and subsequently cope with increased stress using suboptimal strategies (e.g. substance misuse). The biologic effects of relatively diverse adverse experiences are thought to have similar mechanisms (Nusslock & Miller, 2016) involving adjustments within the HPA axis (Anacker et al., 2014).

In women, early life adversity is associated with persistent changes in stress reactivity in both autonomic and HPA regulatory systems (Heim et al., 2000; Li & Seng, 2018; Shea, Walsh, MacMillan, & Steiner, 2005), including altered cortisol parameters (Jogems-Kosterman et al., 2007) and more variable vasovagal heart rate responses (Rice & Records, 2006). Authors of a meta-analysis found significant effects of early life adversity on the cortisol response to social stress, and that these effects reach a peak in adulthood and are more pronounced in women (Bunea et al., 2017)

Pregnancy is also associated with regulatory changes within the HPA axis. The placenta, functioning as a transient endocrine organ, causes cortisol levels to increase during the 3rd trimester in preparation for birth (Costa, 2016; Wadhwa et al., 1996). Potentially detrimental levels of cortisol may cross the placenta if maternal elevations are too high (Glover et al., 2010; Reynolds, 2013; Solano & Arck, 2020). Maternal cortisol alterations during pregnancy are linked to structural brain alterations in infants, impaired cognitive performance in children (Davis et al., 2017), and child psychopathology (Isaksson et al., 2015).

In recent years, a growing number of researchers have examined the programming effects of early life events on cortisol parameters during pregnancy. Among existing studies, researchers have used a wide variety of methods to measure cortisol in pregnant women. Measures of HPA cortisol output can be disaggregated into physiologically distinct parameters (tonic, diurnal and phasic) which have been differentially linked to early life and current stressors (Dobler et al., 2019). While several authors have reviewed the effects of early life adversity in non-pregnant women (Bunea et al., 2017; Li & Seng, 2018), we are not aware that any authors have addressed the effects of early life adversity on cortisol in pregnant women. Thus, the objective of this integrative review was to synthesize published findings on the relationship between early life adversity and HPA cortisol parameters in pregnant women.

Methods

Data Sources

We selected the integrative review method by Whittemore and Knafl (2005) to accommodate the use of diverse methods across studies. The steps of this approach include problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis, and presentation (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). We conducted a literature search to locate studies that examined the relationship between early life adversity in women and HPA regulation of cortisol during pregnancy. Databases included PubMed, CINAHL, and PsychINFO. We also examined reference lists of the included articles for additional eligible studies. The search terms included a combination of the keywords early life adversity, childhood trauma, pregnancy, HPA, and cortisol (Table S1). Year of publication was unrestricted through May 2020.

Study Selection

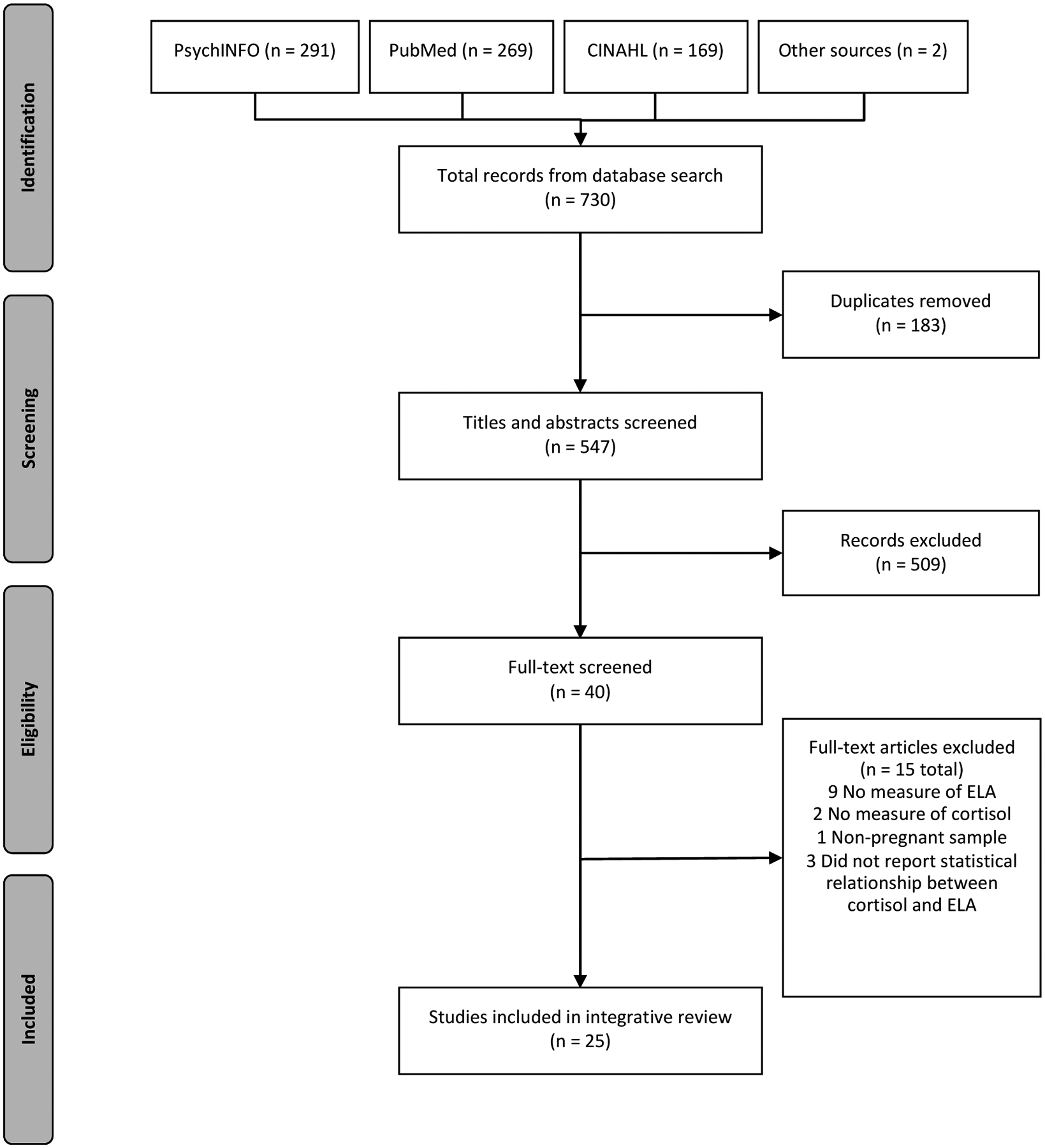

Figure 1 displays a flowchart of the study selection procedures as outlined by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. We included articles if they met the following criteria: 1) reported on a sample of women who were currently or recently pregnant, 2) included at least one measure of cortisol in pregnant women, 3) included a measure of early life adversity, 4) reported on the statistical relationship between early life adversity and cortisol, 5) published in English in a peer-reviewed journal, and 6) was of sufficient methodological quality. Database filters were used to exclude reviews, animal studies, and articles written in a language besides English. In total, the literature search resulted in 730 records. We removed 183 duplicate records and screened 547 titles/abstracts. We reviewed 40 full-text articles, 15 of which we excluded (Figure 1). A total of 25 full-text articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in our review (Table S2).

Figure 1.

Search strategy for comprehensive literature review.

Data Evaluation, Quality, and Risk of Bias

We critically appraised all articles for internal validity and risk of bias using the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Quality Assessment Tools (2014). A list of criteria and ratings for each article are included in Tables S3 to S6. The first author used the Quality Assessment Tools to rate the overall risk of bias for each article as either “good” (low risk of bias), “fair” (susceptible to some bias), or “poor” (significant risk of bias). In order to be included in the review, studies needed to receive a rating of at least “Good” or “Fair.” More weight was given to articles rated as “good” compared to articles rated as “fair.” The overall quality was “good” for 20 articles and “fair” for four articles.

Results

Description of Included Studies

Twenty-five articles, describing fifteen unique studies, were identified for inclusion in the review and are summarized in Table S2. Articles were published between 2007 and 2020. Most studies were conducted with samples of women living in the United States (68%, n = 17). Four studies were conducted in Canada, two in Germany, one in Denmark, and one in Peru. The mean age of participants in European and Canadian studies tended to be older (mean age range: 30–36 years) than studies conducted in South America and the US (mean age range: 22 – 31 years). All studies were prospective, with either cross-sectional (n = 16) or longitudinal (n = 9) designs. Sample sizes ranged from 17 (Bublitz et al., 2016) to 395 participants (Seng et al., 2018). Thirteen of the articles were the results of large cohort studies and two additional articles were subset/pilot studies within the larger cohort studies.

Measures of Early Life Adversity

Investigators used several different measures to quantify early life adversity. The Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale (ACE) measures 10 categories of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction (Dube et al., 2003) and was the most commonly used measure (n = 10 studies; Bowers et al., 2018; Bublitz et al., 2014, 2016; Bublitz & Stroud, 2012, 2013; Hantsoo et al., 2019; Nyström-Hansen et al., 2019; Thomas-Argyriou et al., 2020; Thomas, Letourneau, et al., 2018; Thomas, Magel, et al., 2018). The Life Stressor Checklist is a 30-item scale of stressful life events (Wolfe & Kimerling, 1997) and was used in five articles (Bosquet Enlow et al., 2017; Flom et al., 2018; King et al., 2008; Schreier et al., 2016; Seng et al., 2018). The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) is a 28-item scale with five subscales measuring physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, and physical / emotional neglect (Bernstein et al., 1994) and was used in five articles (Deuschle et al., 2018; Schreier et al., 2015; Schury et al., 2017; Shea et al., 2007; Stephens et al., 2020). The Stress and Adversity Inventory (STRAIN) is a 96-item measure of cumulative stress over the life course (Slavich & Epel, 2010) and was used in two articles (Epstein et al., 2020; Gillespie et al., 2017). Swales et al (2018) used the Life Events Checklist assessing exposure to 16 potentially traumatic events (Gray et al., 2004). Orta et al. (2020) used a yes/no question regarding prior experience of physical and/or sexual abuse during childhood. Bosquet Enlow et al. (2019) used parental homeownership during childhood as an indicator of childhood socioeconomic status.

Measures of Cortisol

Cortisol was most commonly sampled in saliva (n = 12 studies) but was also measured in hair (n = 10 studies), plasma (n = 2 studies), and amniotic fluid (n = 1 studies). Depending on the source and timing of sampling, various cortisol measures represent physiologically distinct aspects of HPA function, which we have delineated into the following parameters: diurnal, phasic, tonic, and pregnancy-related changes (Table 7; Dobler et al., 2019; Schalinski et al., 2015).

Table 7.

Synthesis of findings on cortisol parameters associated with early life adversity

| Cortisol Parameters | Physiologic Definition | Measure (Common source of biospecimen) | Functional Significance | Findings Associated with Early Life Adversity | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diurnal Cortisol Rhythm | The daily rhythm of cortisol is characterized by high cortisol upon awakening and a gradual decline of cortisol across the day, reaching low levels near bedtime. |

|

The pulse of cortisol in the morning (CAR) facilitates wakefulness, consciousness, and energy mobilization for the demands of the day ahead. The decline of cortisol over the day (cortisol slope), especially near bedtime facilitates the onset of sleep. |

|

|

| Phasic (acute) Cortisol Response | Distinct cortisol response to an acute stressor. | Cortisol response to a defined laboratory stressor or a naturally occurring stressor

|

This is the “fight or flight” response that prepares the body to effectively respond to stressful stimuli. An altered response may include an exaggerated or a blunted/delayed acute stress response, and/or inadequate or prolonged recovery. |

|

|

| Tonic (baseline) Cortisol | The estimate of basal cortisol levels under neutral or non-stress conditions; average cortisol levels or overall amount secreted over time. |

|

Elevated tonic cortisol may indicate glucocorticoid resistance at the cellular level, in which more cortisol is needed throughout the body in order to elicit cellular responses. Higher tonic cortisol may pass through the placenta to affect fetal brain development. |

|

|

| Pregnancy-Related Cortisol Change | By late pregnancy, cortisol increases 2–3-fold compared to pre-pregnancy levels. The diurnal rhythm is preserved, with some evidence of blunted acute stress response and blunted CAR. | Repeated measurements of diurnal, phasic, and tonic parameters across the course of gestation (saliva, plasma, hair) | Higher levels of cortisol toward the end of pregnancy promote the cascade of physiologic events which lead to the onset of labor. The blunting of the CAR and blunting of acute cortisol responses towards late pregnancy theoretically function to protect the fetal brain from cortisol over-exposure and from spontaneous onset of preterm labor. |

|

Note. CAR = cortisol awakening response; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder

The diurnal pattern of cortisol across the day is characterized by higher levels of cortisol in the morning and lower levels in the evening. An increase or surge in cortisol occurs approximately 30 to 45 minutes after awakening, known as the cortisol awakening response (CAR; Wilhelm et al., 2007). The diurnal slope is the rate of cortisol recovery (i.e. decline) between awakening and bedtime samples. Flatter diurnal slopes (i.e., reduced recovery) have been associated with worse physical and mental health outcomes (Adam et al., 2017). The phasic cortisol response is an individual’s response to an acute stressor. It is measured in saliva or plasma, usually resulting in distinct pulses of cortisol above baseline in response to a stressor (Dobler et al., 2019).

Tonic cortisol is an estimate of average, basal cortisol level under non-stress conditions (Dobler et al., 2019). Tonic cortisol can be estimated using various measures, including a single sample of blood or saliva (under non-stress conditions), total area under the curve (AUC) calculated from multiple saliva samples over the course of one or more days, or hair cortisol (Schalinski et al., 2015; Short et al., 2016). Hair cortisol measures provide estimates of integrated cortisol secretion over a month or more of time reflecting long-term systemic cortisol levels. Each centimeter of hair (beginning from the scalp) corresponds to average cortisol levels for the previous month (Stalder & Kirschbaum, 2012). Neither blood, salivary nor hair cortisol estimates account for differences in placental metabolism of cortisol to its inactive form cortisone. Decreased metabolism of cortisol by the placenta is associated with maternal depression, anxiety, and chronic stress, leading to increased fetal exposure to maternal cortisol (Seth et al., 2015; Welberg et al., 2005). Thus, amniotic cortisol is a more proximal measure of fetal exposure to maternal cortisol (Deuschle et al., 2018).

Pregnancy-specific changes are evident across diurnal, phasic, and tonic parameters during pregnancy. Tonic cortisol levels increase two to four-fold by the end of pregnancy, driven by positive cortisol feedback within the placenta (Duthie & Reynolds, 2013; Kammerer et al., 2006). As pregnancy advances, the phasic cortisol response to stressors typically attenuates (Entringer et al., 2010). Similarly, both the CAR and the diurnal slope typically flatten towards the end of pregnancy (Entringer et al., 2010).

Synthesis of Findings

Diurnal cortisol.

Early life adversity was associated with a significantly larger CAR in four out of five unique studies that reported on this relationship (Bublitz & Stroud, 2012; Epstein et al., 2020; Stephens et al., 2020; Thomas, Magel, et al., 2018). In the first study to examine this relationship, Shea et al. (2007) reported no significant relationship between childhood trauma and the CAR in a sample of pregnant Canadian women (N = 66, mean = 28 weeks gestation). In contrast, Bublitz and Stroud (2012) subsequently reported a significant positive association between childhood sexual abuse and CAR in late pregnancy (mean = 35 weeks gestation) in a larger, more diverse sample of pregnant women in the US (N = 135). Stephens et al. (2020) reported similar findings on the relationship between childhood sexual abuse and elevated CAR in pregnancy (N = 178). Along these lines, Thomas, Magel, et al. reported a 2.5-fold increased CAR in women during early pregnancy (N =356, mean = 11.4 weeks gestation) who had experienced four or more adverse childhood experiences. Similarly, we reported a significantly larger CAR in pregnant women (N = 58, mean = 27 weeks gestation) who had experienced early life adversity (Epstein et al., 2020). Notably, these effects were consistently independent of current stressors (Epstein et al., 2020; Stephens et al., 2020; Thomas, Magel, et al., 2018). Stephens et al. (2020) also reported a slower CAR decline (i.e., recovery) at 60 minutes after awakening in women with higher levels of childhood adversity.

Reports on the relationship between diurnal cortisol slope and early life adversity were mixed (Bublitz & Stroud, 2012; Epstein et al., 2020; Stephens et al., 2020; Thomas, Magel, et al., 2018). Bublitz and Stroud (2012) reported no group differences for diurnal cortisol slope according to childhood abuse exposure. In contrast, Thomas, Magel, et al. (2018) subsequently reported that adverse childhood experiences were associated with a flatter diurnal cortisol slope. Recently, we reported that greater childhood stress was significantly associated with steeper diurnal cortisol slope, but only in women with high adulthood stress (Epstein et al., 2020). Stephens et al. (2020) reported that the effects of early life adversity on diurnal cortisol slope may have different pathways that are specific to the type of adversity, finding that only childhood economic disadvantage, but not childhood trauma, predicted flatter diurnal cortisol slope (Stephens et al., 2020). Conflicting findings could be due to differing demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the samples, as well as inconsistencies in measurement and methods of cortisol sampling across studies.

Phasic cortisol.

Early life adversity was associated with a blunted and/or delayed response to acute and momentary stressors in three studies (Bublitz et al., 2016; Bublitz & Stroud, 2013; Hantsoo et al., 2019). Bublitz and colleagues (Bublitz et al., 2016; Bublitz & Stroud, 2013) reported on two studies of cortisol response to momentary stressors during pregnancy. In the first study (N = 41), they found that childhood sexual abuse was associated with greater morning cortisol in relation to prior day stress and greater evening cortisol in relation to same-day stress (20 – 35 weeks gestation), indicating delayed, prolonged, and/or reduced recovery from stressors (Bublitz & Stroud, 2013). In a second pilot study (N = 17), they found that pregnant women (27 – 34 weeks gestation) exposed to adverse childhood experiences had a smaller, blunted cortisol response to momentary stress compared to non-abused women (Bublitz et al., 2016). Similarly, in a small study (N = 19) in which pregnant women underwent a standardized social stress test (Trier Social Stress Test) between 24 and 32 weeks gestation, women with two or more adverse childhood experiences were significantly less likely to show any cortisol response to the stressor, compared to women with only 1 or no adverse events (Hantsoo et al., 2019).

Tonic cortisol.

Early life adversity was associated with elevations in tonic cortisol, but only in relation to current stressors such as psychological distress (Bowers et al., 2018), low social support (Thomas, Letourneau, et al., 2018), low socioeconomic status (Bosquet Enlow et al., 2019), and adulthood trauma (Swales et al., 2018). Higher tonic cortisol levels were also reported among Black pregnant women (Gillespie et al., 2017; Schreier et al., 2015, 2016). No significant direct associations between cortisol AUC and early life adversity were reported (Epstein et al., 2020; Thomas, Letourneau, et al., 2018; Walsh et al., 2016). Similarly, Seng et al. (2018) measured cortisol three times a day (awakening, evening, and bedtime), up to 12 days over the duration of pregnancy and found no differences in cortisol at any point during the day between pregnant women with trauma exposure or PTSD compared to non-exposed women. However, they did find that a subgroup of traumatized women with dissociative symptoms of PTSD had markedly increased basal cortisol throughout the day and across pregnancy, particularly later in the day and prior to 34 weeks gestation. King et al. (2008) reported on the effects of trauma history, post-traumatic stress, chronic stress, and other potential confounding variables on tonic evening cortisol in pregnant women (N = 214). While they found no direct effects of child abuse history on evening cortisol, they found that child abuse history was significantly correlated with lifetime PTSD diagnosis, smoking, and sociodemographic stress, each of which significantly predicted higher evening cortisol levels (King et al., 2008). In regard to amniotic cortisol, Deuschle et al. (2018) reported on a study of European pregnant women (N = 79, mean gestational week = 16) undergoing amniocentesis and found that childhood trauma scores did not predict amniotic cortisol levels.

Among the hair cortisol studies, researchers reported mostly null findings in relation to early life adversity (Bosquet Enlow et al., 2018, 2019; Bowers et al., 2018; Flom et al., 2018; Nyström-Hansen et al., 2019; Orta et al., 2020; Schreier et al., 2015, 2016; Schury et al., 2017; Swales et al., 2018). Schury et al. (2017) analyzed hair cortisol from the 3rd trimester (N = 94) among an older, well-educated sample of German pregnant women and their infants, finding that childhood maltreatment was not associated with cortisol (Schury et al., 2017). These findings were replicated by Nyström-Hansen et al. (2019) (N = 44), finding that child abuse was not associated with 3rd trimester hair cortisol, even in a sample with serious mental illness. Similarly, Bowers et al. (2018) found in a small sample of women (N = 29) in mid-pregnancy that hair cortisol was not directly associated with childhood adversity. However, they found that women with exposure to more than two adverse childhood experiences had higher hair cortisol with increased psychological distress.

In contrast, other investigators reported that factors related to current stress or race moderated and/or mediated the effects of childhood adversity on hair cortisol. For example, in a sample of women at high risk for preterm birth, Swales et al. (2018) reported an interactive effect, such that greater exposure to trauma in adulthood was associated with higher hair cortisol, especially among women who had experienced childhood trauma. In a larger cohort study of pregnant women in the US, sexual and physical abuse were associated with higher hair cortisol, but only among Black women (Schreier et al., 2015). In the same cohort, Schreier et al. (2016) examined overall lifetime traumatic events meeting DSM-V PTSD Criterion A, finding that exposure to more lifetime trauma was significantly associated with greater hair cortisol. After stratifying the results by race, Black women had significantly higher hair cortisol during the 1st, 2nd, and 3 trimesters compared to White women. Along these lines, Gillespie et al. (2017) reported that childhood adversity in a sample of Black pregnant women predicted higher cortisol in a single afternoon plasma sample (N = 89, gestational week = 26.5).

Bosquet Enlow et al. (2017) reported no association between overall maternal lifetime trauma exposure and 3rd trimester hair cortisol levels; however; they found that low socioeconomic status in childhood was associated with higher hair cortisol in each trimester, an effect which was fully mediated by low socioeconomic status in pregnancy (Bosquet Enlow et al., 2019). Similarly, Orta et al. (2020) found that history of child abuse was not significantly associated with prenatal hair cortisol, but that low education (≤ 12 years of school) was associated with higher preconception and 1st trimester hair cortisol level.

Patterns of pregnancy-related cortisol change.

Early life adversity was associated with specific alterations in cortisol longitudinally over the course of pregnancy (Bublitz et al., 2014; Bublitz & Stroud, 2012; Seng et al., 2018; Thomas, Magel, et al., 2018). Bublitz and Stroud (2012) measured salivary cortisol three times during pregnancy and found that the CAR increased over time between 30 and 35 weeks gestation in women with a history of sexual abuse, but decreased in non-abused women. While Thomas, Magel, et al. (2018) did not find effects of early adverse events on CAR trajectory over time, they did observe longitudinal differences in cortisol slope from early to late pregnancy. Women with four or more adverse childhood events had a 17% steepening of the diurnal slope from early pregnancy to late pregnancy, while women with no events showed a 10% flattening of the diurnal slope (Thomas, Magel, et al., 2018).

Likewise, Seng et al. (2018) found that women with trauma-related dissociative symptoms had higher and flatter cortisol levels throughout pregnancy, but most prominently during early pregnancy. Seng et al. explain “psychosexual aspects of pregnancy [can] act as triggers to dissociative symptoms in survivors of childhood maltreatment in particular and result in persistent, enhanced stress reactivity across gestation that is specific to a woman’s experience of pregnancy” (Seng et al., 2018 p. 19). This explanation complements the findings of other studies in this review indicating alterations in HPA regulation that were specific to childhood sexual abuse, in contrast to non-sexual types of abuse (Bublitz et al., 2016; Bublitz & Stroud, 2012, 2013; Stephens et al., 2020).

Discussion

The convergence of evidence suggests several variations in cortisol regulation during pregnancy are associated with early life adversity in women. Direct associations between early adversity and cortisol that were reported independently in more than one study include larger cortisol awakening response (Bublitz & Stroud, 2012; Epstein et al., 2020; Thomas, Magel, et al., 2018) and blunted cortisol response to acute stressors (Bublitz et al., 2016; Hantsoo et al., 2019). These effects appear to be independent of current social stress or psychological symptoms, and are consistent with meta-analysis findings of studies involving non-pregnant samples (Bunea et al., 2017; Fogelman & Canli, 2018).

Early adversity is also associated with reduced recovery of cortisol levels in the evening and higher levels of long-term systemic cortisol during the 3rd trimester in the presence of current stress and/or psychological symptoms (Bosquet Enlow et al., 2019; Bowers et al., 2018; Bublitz & Stroud, 2013; King et al., 2008; Seng et al., 2018; Swales et al., 2018; Thomas, Letourneau, et al., 2018). There appear to be synergistic effects on cortisol, whereby increases in tonic cortisol related to stress and psychological symptoms during pregnancy are exacerbated by the preexisting effects of early life adversity (Bowers et al., 2018; Swales et al., 2018).

Alterations in cortisol associated with early life adversity may reflect adaptive plasticity within the individual to cope with future stressful environments (Ellis & Giudice, 2019). Thus, it is important to note that the cortisol variations described in our review may not only represent “dysregulation” or “maladaptation,” but instead (or additionally) may represent long-term adaptive processes underlying stress resilience (Ellis & Giudice, 2019). In addition to facilitating the stress response, the HPA axis is a broader regulatory system encompassing biorhythmic regulation of sleep-activity, consciousness, learning, memory, energy balance, and the immune response. During pregnancy, cortisol also influences fetal brain development, fetal organ maturation, and the timing of parturition (Challis et al., 2001).

In this review, we sought to develop a more nuanced understanding of the potential effects of early adversity on diverse but inter-related cortisol functions, including the diurnal cortisol rhythm that is part of our circadian system (e.g. awakening, activity, and sleep), baseline or tonic non-stress functioning, response to phasic environmental stressors, and cortisol changes over the course of pregnancy. There is preliminary evidence that HPA regulation of cortisol involves responses to both current stress and psychological symptoms (Bowers et al., 2018; Gillespie et al., 2017; Schreier et al., 2015, 2016; Thomas et al., 2017; Thomas, Magel, et al., 2018), but is also shaped by residuals from early life experiences (Bublitz et al., 2016; Bublitz & Stroud, 2012, 2013; Epstein et al., 2020; Hantsoo et al., 2019; Thomas, Letourneau, et al., 2018; Thomas, Magel, et al., 2018). Overall, findings from the reviewed studies suggest that early life adversity is associated with HPA axis regulation of cortisol in complex and dynamic ways. Furthermore, our review highlights that there are at least four physiologically distinct cortisol parameters (diurnal, phasic, tonic, and pregnancy-related change) to consider when examining HPA axis regulation of cortisol during pregnancy.

Implications

More extensive research is warranted to better understand underlying biological mechanisms that may link early adversity to altered cortisol and how these alterations may affect the health of the fetus, birth outcomes, and the woman’s physical and mental health. Given the HPA axis is not a system unto itself, it is essential to explore how the axis is involved with other regulatory systems in response to early adversity. The HPA neuroendocrine response functions together with the autonomic nervous system (Godoy et al., 2018). Examining the links between cortisol regulation and autonomic nervous system measures such as heart rate variability may contribute a more complete picture of HPA regulation in the context of concurrent physiologic adaptations to pregnancy. In addition, the relationship of cortisol to its precursor hormones (CRH, ACTH) in the HPA axis needs further study to understand nuanced changes in the downstream response to early adversity. Future research could also consider specific cognitive, emotional, and behavioral symptoms and phenotypes associated with HPA variations and early life adversity.

Researchers of the reviewed studies used a variety of methodological approaches. While some authors found that effect sizes were significant only during early pregnancy (Orta et al., 2020; Seng et al., 2018), others reported significant differences only at the end of the 3rd trimester (Bublitz & Stroud, 2012). With regard to early pregnancy differences, Orta et al. noted the possibility of a “ceiling effect” in which effect sizes that are evident in early pregnancy are masked as gestational cortisol levels rise towards the end of pregnancy. Regarding late pregnancy, Bublitz and Stroud (2012) suggest that early abuse may be associated with differences in late pregnancy HPA quiescence, referring to the physiologic blunting of cortisol that normally occurs as gestation advances. This blunting effect theoretically serves to protect the fetal brain from over-exposure to cortisol. As an alternative explanation, they suggest that late-pregnancy cortisol variation could be due to underlying physiologic differences in the fetal-placental unit which plays an important role in regulating the onset of labor (Bublitz & Stroud, 2012). Hence, variation in late pregnancy cortisol could have relevance in predicting onset of preterm labor. Both early and late pregnancy cortisol alterations are likely to influence fetal brain development, but in different ways (Buss et al., 2015; Davis et al., 2017).

Alterations in diurnal and phasic cortisol parameters may underlie psychological and behavioral health risks in pregnant women such as perinatal depression and risk for substance misuse (Hardeveld et al., 2014; Lovallo et al., 2018). For instance, a larger CAR precedes major depressive episodes (Hardeveld et al., 2014) and predicts shorter length of gestation in pregnant women (Buss et al., 2009). Thus, elevated CAR associated with early life adversity in pregnant women may indicate heightened vulnerability for both perinatal depression and preterm birth. Furthermore, Lovallo et al. (2012) reported a dose-response relationship between early life adversity and a blunted cortisol response to acute social stressors. In turn, blunted cortisol response is associated with higher novelty-seeking, disinhibition, unsuccessful smoking cessation, and increased risk for substance use and alcohol addiction (Lovallo et al., 2019; Milivojevic & Sinha, 2018). Understanding the biobehavioral effects of early adversity can help inform compassionate nursing care of pregnant women at risk for adverse health outcomes.

Traditionally, larger sample sizes have been equated with higher quality and greater confidence in the findings; however, the generalizability of group-level data to individual experience, process, or behavior has limitations (Fisher et al., 2018). One such limitation is the wide range of within-individual variability in biomarkers, symptoms, or experiences over time. As health care becomes more individualized, it will be important to further characterize changes over time that are unique to individuals, in addition to cross-sectional differences between groups. Notably, investigators of three reviewed studies with small sample sizes (Bublitz et al., 2016; Bublitz & Stroud, 2013; Hantsoo et al., 2019) addressed both within-person and between-person variables in their analyses. Despite the small sample sizes, these studies yielded informative findings on day-to-day variation in stress-related cortisol, both for individuals over time as well as between groups (e.g. with and without abuse history). Future research designs should consider including individual-level variables over time.

Limitations

Diverse samples and methods, as well as the observational, correlational designs of the reviewed studies limited the ability to make definitive causal conclusions on specific cortisol alterations. However, the heterogeneity among studies illustrated the dynamic nature of cortisol regulation and HPA functioning beyond a simplistic hyper- or hypo-cortisol response. The wide variety of measures used to quantify early life adversity was also a limiting factor, making it difficult to determine whether the same construct was measured across all studies. Furthermore, we did not address other related aspects of this emerging body of research, such as the physiologic mechanisms underlying HPA biomarker changes, fetal or neonatal biomarkers, or offspring developmental outcomes.

Conclusion

Early life adversity is a known risk factor for a variety of perinatal health outcomes, including adverse mental and reproductive outcomes. Since cortisol may be a mediating physiologic mechanism by which early life experience influences health during pregnancy, we sought to summarize available evidence linking early life adversity with altered HPA regulation of cortisol during pregnancy. Among the reviewed studies, we identified four physiologically distinct cortisol parameters (diurnal, phasic, tonic, and pregnancy-related change) that researchers have used to measure HPA cortisol regulation during pregnancy. Preliminary evidence suggests that early life adversity is associated with HPA axis regulation of cortisol across these different parameters. In particular, early life adversity was associated with elevated cortisol awakening response (diurnal) and blunted response to acute and momentary stress (phasic), irrespective of current stress or psychological symptoms. In the context of current stress or psychological symptoms, pregnant women had elevated levels of baseline (tonic) cortisol. In light of these findings, there is a continued need to study how early life adversity influences cortisol regulation, especially as it relates to other variables such as ANS regulation, current stress, psychological symptoms, social support, and health outcomes. Future research in this area may be particularly helpful to promote health among women who are most vulnerable to adverse health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

CALLOUTS.

Variations in the physiologic stress response during pregnancy may help explain differences in health risk behaviors, maternal mental health, and adverse infant health outcomes.

Early life adversity is associated with an elevated cortisol awakening response and a blunted cortisol response to stressors in pregnant women.

Understanding the biobehavioral effects of early adversity can help inform compassionate nursing care of pregnant women who are at risk for adverse health outcomes.

Acknowledgement

Crystal Modde Epstein was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health (Award Numbers F31NR016176; T32NR016920). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest or relevant financial relationships.

Contributor Information

Crystal Modde Epstein, School of Nursing, University of North Carolina Greensboro..

Julia F. Houfek, College of Nursing, University of Nebraska Medical Center Omaha, NE..

Michael J. Rice, College of Nursing University of Colorado Denver, Aurora, CO..

Sandra J. Weiss, School of Nursing, University of California, San Francisco..

References

- Adam EK, Quinn ME, Tavernier R, McQuillan MT, Dahlke KA, & Gilbert KE (2017). Diurnal cortisol slopes and mental and physical health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 83, 25–41. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.05.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anacker C, O’Donnell KJ, & Meaney MJ (2014). Early life adversity and the epigenetic programming of hypothalamic-pituitary- adrenal function. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 16(3), 321–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, Sapareto E, & Ruggiero J (1994). Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 151(8), 1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blalock JA, Nayak N, Wetter DW, Schreindorfer L, Minnix JA, Canul J, & Cinciripini PM (2011). The relationship of childhood trauma to nicotine dependence in pregnant smokers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25(4), 652–663. 10.1037/a0025529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosquet Enlow M, Bollati V, Sideridis G, Flom JD, Hoxha M, Hacker MR, & Wright RJ (2018). Sex differences in effects of maternal risk and protective factors in childhood and pregnancy on newborn telomere length. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.05.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosquet Enlow M, Devick KL, Brunst KJ, Lipton LR, Coull BA, & Wright RJ (2017). Maternal lifetime trauma exposure, prenatal cortisol, and infant negative affectivity. Infancy, 22(4), 492–513. 10.1111/infa.12176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosquet Enlow M, Sideridis G, Chiu Y-HM, Nentin F, Howell EA, Le Grand BA, & Wright RJ (2019). Associations among maternal socioeconomic status in childhood and pregnancy and hair cortisol in pregnancy. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 99, 216–224. 10.1016/J.PSYNEUEN.2018.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers K, Ding L, Gregory S, Yolton K, Ji H, Meyer J, Ammerman RT, Van Ginkel J, & Folger A (2018). Maternal distress and hair cortisol in pregnancy among women with elevated adverse childhood experiences. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 95, 145–148. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bublitz MH, Bourjeily G, Vergara-Lopez C, & Stroud LR (2016). Momentary stress, cortisol, and gestational length among pregnant victims of childhood maltreatment: A pilot study. Obstetric Medicine, 9(2), 73–77. 10.1177/1753495X16636264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bublitz MH, Parade SH, & Stroud LR (2014). The effects of childhood sexual abuse on cortisol trajectories in pregnancy are moderated by current family functioning. Biological Psychology, 103(1), 152–157. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2014.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bublitz MH, & Stroud LR (2012). Childhood sexual abuse is associated with cortisol awakening response over pregnancy: Preliminary findings. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(9), 1425–1430. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bublitz MH, & Stroud LR (2013). Maternal history of child abuse moderates the association between daily stress and diurnal cortisol in pregnancy: A pilot study. Stress, 16(6), 706–710. 10.3109/10253890.2013.825768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunea IM, Szentágotai-Tătar A, Miu AC, Szentágotai-Tǎtar A, & Miu AC (2017). Early-life adversity and cortisol response to social stress: A meta-analysis. Translational Psychiatry, 7(12), 1–8. 10.1038/s41398-017-0032-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss C, Entringer S, Reyes JF, Chicz-DeMet A, Sandman CA, Waffarn F, & Wadhwa PD (2009). The maternal cortisol awakening response in human pregnancy is associated with the length of gestation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 201(4), 398.e1–398.e8. 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.06.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss C, Graham AM, Rasmussen J, Entringer S, Gilmore JH, Styner M, Wadhwa PD, & Fair DA (2015). Lack of maternal stress dampening during pregnancy is associated with altered neonatal amygdala connectivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 61, 11–12. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.07.419 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cammack AL, Buss C, Entringer S, Hogue CJ, Hobel CJ, & Wadhwa PD (2011). The association between early life adversity and bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 204(5), 431.e1–431.e8. 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.01.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challis JRG, Sloboda D, Matthews SG, Holloway A, Alfaidy N, Patel FA, Whittle W, Fraser M, Moss TJM, & Newnham J (2001). The fetal placental hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, parturition and post natal health. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 185, 135–144. 10.1016/S0303-7207(01)00624-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KW, & Sikkema KJ (2016). Childhood maltreatment and perinatal mood and anxiety disorders: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 17(5), 427–453. 10.1177/1524838015584369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiaens I, Hegadoren K, & Olson DM (2015). Adverse childhood experiences are associated with spontaneous preterm birth: A case-control study. BMC Medicine, 13(1), 120–124. 10.1186/s12916-015-0353-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa MA (2016). The endocrine function of human placenta: An overview. Reproductive BioMedicine Online, 32(1), 14–43. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2015.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CSM, Callaghan BL, Kan JM, & Richardson R (2016). The lasting impact of early-life adversity on individuals and their descendants: Potential mechanisms and hope for intervention. Genes, Brain and Behavior, 15(1), 155–168. 10.1111/gbb.12263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis EP, Head K, Buss C, & Sandman CA (2017). Prenatal maternal cortisol concentrations predict neurodevelopment in middle childhood. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 75, 56–63. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuschle M, Hendlmeier F, Witt S, Rietschel M, Gilles M, Sánchez-Guijo A, Fañanas L, Hentze S, Wudy SA, & Hellweg R (2018). Cortisol, cortisone, and BDNF in amniotic fluid in the second trimester of pregnancy: Effect of early life and current maternal stress and socioeconomic status. Development and Psychopathology, 30(3), 971–980. 10.1017/S0954579418000147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobler VB, Neufeld SAS, Fletcher PF, Perez J, Subramaniam N, Teufel C, & Goodyer IM (2019). Disaggregating physiological components of cortisol output: A novel approach to cortisol analysis in a clinical sample – A proof-of-principle study. Neurobiology of Stress, 10, 1–10. 10.1016/j.ynstr.2019.100153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, & Giles WH (2001). Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: Findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 286(24), 3089–3096. 10.1001/jama.286.24.3089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Chapman DP, Giles WH, & Anda RF (2003). Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. Pediatrics, 111(3), 564–572. 10.1542/peds.111.3.564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duthie L, & Reynolds RM (2013). Changes in the maternal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in pregnancy and postpartum: Influences on maternal and fetal outcomes. Neuroendocrinology, 98(2), 106–115. 10.1159/000354702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, & Giudice M Del. (2019). Developmental adaptation to stress: An evolutionary perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 70, 111–139. 10.1146/annurev-psych-122216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entringer S, Buss C, Shirtcliff EA, Cammack AL, Yim IS, Chicz-DeMet A, Sandman CA, & Wadhwa PD (2010). Attenuation of maternal psychophysiological stress responses and the maternal cortisol awakening response over the course of human pregnancy. Stress, 13(3), 258–268. 10.3109/10253890903349501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein CM, Houfek JF, Rice MJ, Weiss SJ, French JA, Kupzyk KA, Hammer SJ, & Pullen CH (2020). Early life adversity and depressive symptoms predict cortisol in pregnancy. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 23(3), 379–389. 10.1007/s00737-019-00983-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP, & Marks JS (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher AJ, Medaglia JD, & Jeronimus BF (2018). Lack of group-to-individual generalizability is a threat to human subjects research. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(27), 1–10. 10.1073/pnas.1711978115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flom JD, Chiu YHM, Hsu HHL, Devick KL, Brunst KJ, Campbell R, Enlow MB, Coull BA, & Wright RJ (2018). Maternal lifetime trauma and birthweight: Effect modification by in utero cortisol and child sex. Journal of Pediatrics, 203, 301–308. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogelman N, & Canli T (2018). Early life stress and cortisol: A meta-analysis. Hormones and Behavior, 98, 63–76. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2017.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie SL, Christian LM, Alston AD, & Salsberry PJ (2017). Childhood stress and birth timing among African American women: Cortisol as biological mediator. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 84, 32–41. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover V, O’Connor TG, & O’Donnell K (2010). Prenatal stress and the programming of the HPA axis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(1), 17–22. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godoy LD, Rossignoli MT, Delfino-Pereira P, Garcia-Cairasco N, & de Lima Umeoka EH (2018). A comprehensive overview on stress neurobiology: Basic concepts and clinical implications. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 12, 1–23. 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray MJ, Litz BT, Hsu JL, & Lombardo TW (2004). Psychometric properties of the Life Events Checklist. Assessment, 11(4), 330–341. 10.1177/1073191104269954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantsoo L, Jašarević E, Criniti S, McGeehan B, Tanes C, Sammel MD, Elovitz MA, Compher C, Wu G, & Epperson CN (2019). Childhood adversity impact on gut microbiota and inflammatory response to stress during pregnancy. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 75, 240–250. 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeveld F, Spijker J, Vreeburg SA, De Graaf R, Hendriks SM, Licht CMM, Nolen WA, Penninx BWJH, & Beekman ATF (2014). Increased cortisol awakening response was associated with time to recurrence of major depressive disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 50, 62–71. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim CM, Newport DJ, Heit S, Graham YP, Wilcox M, Bonsall R, Miller AH, & Nemeroff CB (2000). Pituitary-adrenal and automatic responses to stress in women after sexual and physical abuse in childhood. Journal of the American Medical Association, 284(5), 592–597. 10.1001/jama.284.5.592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim CM, Shugart M, Craighead WE, & Nemeroff CB (2010). Neurobiological and psychiatric consequences of child abuse and neglect. Developmental Psychobiology, 52(7), 671–690. 10.1002/dev.20494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaksson J, Lindblad F, Valladares E, & Högberg U (2015). High maternal cortisol levels during pregnancy are associated with more psychiatric symptoms in offspring at age of nine - A prospective study from Nicaragua. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 71, 97–102. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jogems-Kosterman BJM, de Knijff DWW, Kusters R, & van Hoof JJM (2007). Basal cortisol and DHEA levels in women with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 41(12), 1019–1026. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammerer MH, Taylor A, & Glover V (2006). The HPA axis and perinatal depression: A hypothesis. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 9(4), 187–196. 10.1007/s00737-006-0131-2 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, & Aggen SH (2014). Clarifying the causal relationship in women between childhood sexual abuse and lifetime major depression. Psychological Medicine, 44(6), 1213–1221. 10.1017/S0033291713001797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AP, Leichtman JN, Abelson JL, Liberzon I, & Seng JS (2008). Ecological salivary cortisol analysis - Part 2: Relative impact of trauma history, posttraumatic stress, comorbidity, chronic stress, and known confounds on hormone levels. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 14(4), 285–296. 10.1177/1078390308321939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, & Seng JS (2018). Child maltreatment trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and cortisol levels in women: A literature review. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 24(1), 35–44. 10.1177/1078390317710313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovallo WR, Acheson A, Vincent AS, Sorocco KH, & Cohoon AJ (2018). Early life adversity diminishes the cortisol response to opioid blockade in women: Studies from the Family Health Patterns Project. PLoS ONE, 13(10), e0205723. 10.1371/journal.pone.0205723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovallo WR, Cohoon AJ, Acheson A, Sorocco KH, & Vincent AS (2019). Blunted stress reactivity reveals vulnerability to early life adversity in young adults with a family history of alcoholism. Addiction, 114(5), 798–806. 10.1111/add.14501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovallo WR, Farag NH, Sorocco KH, Cohoon AJ, & Vincent AS (2012). Lifetime adversity leads to blunted stress axis reactivity: Studies from the Oklahoma Family Health Patterns Project. Biological Psychiatry, 71(4), 344–349. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milivojevic V, & Sinha R (2018). Central and peripheral biomarkers of stress response for addiction risk and relapse vulnerability. Trends in Molecular Medicine, 24(2), 173–186. 10.1016/j.molmed.2017.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. (2014). Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools [Google Scholar]

- Negriff S, Schneiderman JU, & Trickett PK (2015). Child maltreatment and sexual risk behavior: Maltreatment types and gender differences. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 36(9), 708–716. 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusslock R, & Miller GE (2016). Early-life adversity and physical and emotional health across the lifespan: A neuroimmune network hypothesis. Biological Psychiatry, 80(1), 23–32. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyström-Hansen M, Andersen MS, Khoury JE, Davidsen K, Gumley A, Lyons-Ruth K, MacBeth A, & Harder S (2019). Hair cortisol in the perinatal period mediates associations between maternal adversity and disrupted maternal interaction in early infancy. Developmental Psychobiology, 61(4), 543–556. 10.1002/dev.21833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen JM (2018). Integrative review of pregnancy health risks and outcomes associated with adverse childhood experiences. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 47(6), 783–794. 10.1016/j.jogn.2018.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orta OR, Tworoger SS, Terry KL, Coull BA, Gelaye B, Kirschbaum C, Sanchez SE, Williams MA, Moffitt L, & Perinatal NM (2020). Stress and hair cortisol concentrations from preconception to the third trimester. Stress, 22(1), 60–69. 10.1080/10253890.2018.1504917.Stress [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Records K, & Rice MJ (2005). A comparative study of postpartum depression in abused and nonabused women. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 19(6), 281–290. 10.1016/j.apnu.2005.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds RM (2013). Glucocorticoid excess and the developmental origins of disease: Two decades of testing the hypothesis - 2012 Curt Richter Award Winner. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 38(1), 1–11. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice MJ, & Records K (2006). Cardiac response rate variability in physically abused women of childbearing age. Biological Research for Nursing, 7(3), 204–213. 10.1177/1099800405283567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalinski I, Elbert T, Steudte-Schmiedgen S, & Kirschbaum C (2015). The cortisol paradox of trauma-related disorders: Lower phasic responses but higher tonic levels of cortisol are associated with sexual abuse in childhood. PLoS ONE, 10(8), 1–18. 10.1371/journal.pone.0136921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreier HMC, Bosquet Enlow M, Ritz T, Coull BA, Gennings C, Wright RORJ, & Wright RORJ (2016). Lifetime exposure to traumatic and other stressful life events and hair cortisol in a multi-racial/ethnic sample of pregnant women. Stress, 19(1), 45–52. 10.3109/10253890.2015.1117447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreier HMC, Bosquet Enlow M, Ritz T, Gennings C, & Wright RJ (2015). Childhood abuse is associated with increased hair cortisol levels among urban pregnant women. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 69(12), 1169–1174. 10.1136/jech-2015-205541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schury K, Koenig AM, Isele D, Hulbert AL, Krause S, Umlauft M, Kolassa S, Ziegenhain U, Karabatsiakis A, Reister F, Guendel H, Fegert JM, & Kolassa IT (2017). Alterations of hair cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone in mother-infant-dyads with maternal childhood maltreatment. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 1–10. 10.1186/s12888-017-1367-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selk SC, Rich-Edwards JW, Koenen K, & Kubzansky LD (2016). An observational study of type, timing, and severity of childhood maltreatment and preterm birth. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 70(6), 589–595. 10.1136/jech-2015-206304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seng JS, Li Y, Yang JJ, King AP, Low LMK, Sperlich M, Rowe H, Lee H, Muzik M, Ford JD, Liberzon I, & Kane Low LM (2018). Gestational and postnatal cortisol profiles of women with posttraumatic stress disorder and the dissociative subtype. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 47(1), 12–22. 10.1016/j.jogn.2017.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth S, Lewis AJ, Saffery R, Lappas M, & Galbally M (2015). Maternal prenatal mental health and placental 11β-HSD2 gene expression: Initial findings from the Mercy Pregnancy and Emotional Wellbeing Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 16(11), 27482–27496. 10.3390/ijms161126034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea AK, Streiner DL, Fleming A, Kamath MV, Broad K, & Steiner M (2007). The effect of depression, anxiety and early life trauma on the cortisol awakening response during pregnancy: Preliminary results. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 32, 1013–1020. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea AK, Walsh C, MacMillan H, & Steiner M (2005). Child maltreatment and HPA axis dysregulation: Relationship to major depressive disorder and post traumatic stress disorder in females. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 30(2), 162–178. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short SJ, Stalder T, Marceau K, Entringer S, Moog NK, Shirtcliff EA, Wadhwa PD, & Buss C (2016). Correspondence between hair cortisol concentrations and 30-day integrated daily salivary and weekly urinary cortisol measures. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 71, 12–18. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavich GM, & Epel ES (2010). The Stress and Adversity Inventory (STRAIN): An automated system for assessing cumulative stress exposure. University of California, Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Smith MV, Gotman N, & Yonkers KA (2016). Early childhood adversity and pregnancy outcomes. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20(4), 790–798. 10.1007/s10995-015-1909-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solano ME, & Arck PC (2020). Steroids, pregnancy and fetal development. Frontiers in Immunology, 10, 1–13. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.03017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalder T, & Kirschbaum C (2012). Analysis of cortisol in hair - State of the art and future directions. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 26(7), 1019–1029. 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens JE, Kessler CL, Buss C, Miller GE, Grobman WA, Keenan-Devlin L, Borders AE, & Adam EK (2020). Early and current life adversity: Past and present influences on maternal diurnal cortisol rhythms during pregnancy. Developmental Psychobiology, 1–15. 10.1002/dev.22000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swales DA, Stout-Oswald SA, Glynn LM, Sandman C, Wing DA, & Davis EP (2018). Exposure to traumatic events in childhood predicts cortisol production among high risk pregnant women. Biological Psychology, 139, 186–192. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2018.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas-Argyriou JC, Letourneau N, Dewey D, Campbell TS, & Giesbrecht GF (2020). The role of HPA-axis function during pregnancy in the intergenerational transmission of maternal adverse childhood experiences to child behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology, 1–17. 10.1017/S0954579419001767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JC, Letourneau N, Bryce CI, Campbell TS, & Giesbrecht GF (2017). Biological embedding of perinatal social relationships in infant stress reactivity. Developmental Psychobiology, 59(4), 425–435. 10.1002/dev.21505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JC, Letourneau N, Campbell TS, & Giesbrecht GF (2018). Social buffering of the maternal and infant HPA axes: Mediation and moderation in the intergenerational transmission of adverse childhood experiences. Development and Psychopathology, 30(3), 921–939. 10.1017/S0954579418000512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JC, Magel C, Tomfohr-Madsen L, Madigan S, Letourneau N, Campbell TS, & Giesbrecht GF (2018). Adverse childhood experiences and HPA axis function in pregnant women. Hormones and Behavior, 102, 10–22. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2018.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadhwa PD, Dunkel-Schetter C, Chicz-DeMet A, Porto M, & Sandman CA (1996). Prenatal psychosocial factors and the neuroendocrine axis in human pregnancy. Psychosomatic Medicine, 58(5), 432–446. 10.1097/00006842-199609000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh K, Basu A, Werner E, Lee S, Feng T, Osborne LM, Rainford A, Gilchrist M, & Monk C (2016). Associations among child abuse, depression, and interleukin-6 in pregnant adolescents: Paradoxical findings. Psychosomatic Medicine, 78(8), 920–930. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000344 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss S, Muzik M, Deligiannidis K, Ammerman R, Guille C, & Flynn H (2016). Gender differences in suicidal risk factors among individuals with mood disorders. Journal of Depression and Anxiety, 5(1). 10.4172/2167-1044.1000218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Welberg LAM, Thrivikraman KV, & Plotsky PM (2005). Chronic maternal stress inhibits the capacity to up-regulate placental 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 activity. Journal of Endocrinology, 186(3), 7–12. 10.1677/joe.1.06374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore R, & Knafl K (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm I, Born J, Kudielka BM, Schlotz W, & Wüst S (2007). Is the cortisol awakening rise a response to awakening? Psychoneuroendocrinology, 32(4), 358–366. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn N, Records K, & Rice M (2003). The relationship between abuse, sexually transmitted diseases, & group B streptococcus in childbearing women. MCN, The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 28(2), 106–110. 10.1097/00005721-200303000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe J, & Kimerling R (1997). Gender issues in the assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder. In Wilson JP & Keane TM (Eds.), Assessing Psychological trauma and PTSD (pp. 192–238). Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.