Abstract

Dopamine transporter (DAT) and sigma-1 receptor (σ1R) are potential therapeutic targets to reduce the psychostimulant effects induced by methamphetamine (METH). Interaction of σ1R with DAT could modulate the binding of METH, but the molecular basis of the association of the two transmembrane proteins, and how their interactions mediate the binding of METH to DAT or σ1R remains unclear. Here, we characterize the protein-ligand and protein-protein interactions at a molecular level by various theoretical approaches. The present results show that METH adopts a different binding pose in the binding pocket of σ1R, and is more likely to act as an agonist. The relatively lower binding affinity of METH to σ1R supports the role of antagonists as inhibitors that protect against METH-induced effects. We demonstrate that σ1R could bind to Drosophila melanogaster DAT (dDAT) through interactions with either the transmembrane helix α12 or α5 of dDAT. Our results showed that the truncated σ1R displays stronger association with dDAT than the full-length σ1R. Although different helix-helix interactions between σ1R and dDAT lead to distinct effects on the dynamics of individual protein, both associations attenuate the binding affinity of METH to dDAT, particularly in the interactions with the helix α5 of dDAT. Together, the present study provides the first computational investigation on the molecular mechanism of coupling METH binding and the association of σ1R with dDAT.

Keywords: Dopamine transporter, sigma-1 receptor, methamphetamine, association, binding affinity

Graphical Abstract

Association of dopamine transporter (DAT) with sigma-1 receptor (σ1R) mitigates the binding affinity of methamphetamine (METH) to DAT via interactions through transmembrane helix of σ1R with transmembrane helix α12 or α5 of DAT.

1. INTRODUCTION

The neurotransmitter dopamine (DA) is essential for many functions including movement, cognition, mood, and reward (Vaughan & Foster, 2013). The dopaminergic signaling in the brain is modulated by the dopamine transporter (DAT), which is a key transmembrane protein that reuptakes DA from the synaptic cleft into the neuron (Leviel, 2011; Vaughan & Foster, 2013). DAT is a member of the family of neurotransmitter:sodium symporters (NSS), which utilizes the transmembrane sodium gradient as the driving force to transport substrates across the plasma membrane (Cheng & Bahar, 2019; Joseph, Pidathala, Mallela, & Penmatsa, 2019). The availability of high resolution crystal structures of DAT and other NSS proteins reveals that the topology of these transporters contains 12 transmembrane helices and intracellular N- and C-termini (Joseph et al., 2019; K. H. Wang, Penmatsa, & Gouaux, 2015). These transporters work through the proposed alternating access mechanism (Forrest et al., 2008). That is, they could switch between the outward-open and inward-open conformational states, and accordingly, the substrate could alternatively access between the extracellular and intracellular sides of the membrane.

DAT is a major target for psychostimulant drugs such as cocaine (COC) and methamphetamine (METH) that can competitively bind to DAT, block DA transport, and consequently promote extracellular DA levels via different mechanisms (K. H. Wang et al., 2015). On the other hand, the interactions of METH with DAT also stimulate reverse transport of intracellular DA (Vaughan & Foster, 2013). METH has also been reported to damage DA terminals and result in a significant loss of DAT that are associated with neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinsonism (Volkow et al., 2001). The X-ray structures of Drosophila melanogaster DAT (dDAT) bound to different ligands show that distinct classes of ligands such as DA, COC, and METH, bind to the central binding site of the protein in an outward-open conformation (K. H. Wang et al., 2015).

In addition to oligomers formed by self-assembly (Cecchetti, Pyle, & Byrne, 2019; Sitte, 2004; Zhen et al., 2015). DAT may interact with various proteins and hereby regulate its functions. These protein-protein interactions may alter DAT transport capacity and distribution in neurons (Eriksen, Jørgensen, & Gether, 2010). The sigma-1 receptor (σ1R) is a small (28 kDa) transmembrane protein located in the endoplasmic reticulum, and has been implicated in diverse neural mechanisms including the modulation of cell survival and function, calcium signaling, neurotransmitter release, inflammation, and synaptogenesis (L. Nguyen, Kaushal, Robson, & Matsumoto, 2014; L. Nguyen et al., 2015). Moreover, σ1R has been implicated as a potential molecular target for the treatment of psychostimulant addiction (L. Nguyen et al., 2015). The structures of σ1R in complex with diverse ligands were crystallized as trimers, with each protomer containing a single transmembrane helical domain (α1) and a β-barrel fold flanked by four α-helices (α2–α5) (Schmidt, Betz, Dror, & Kruse, 2018; Schmidt et al., 2016). The function of σ1R can be activated by agonists or inhibited by antagonists. The σ1R agonists are indicated to result in monomeric or low-molecular-weight σ1R species, whereas the antagonists shift the receptor toward high-molecular-weight species (Gromek et al., 2014; Mishra et al., 2015; Yano et al., 2018). Upon activation, σ1R could interact with DAT, stabilize the outward-open conformation of DAT, and enhance COC binding (Hong et al., 2017). The association of σ1R with DAT was also reported to attenuate METH-induced dopamine release (Sambo, Lebowitz, & Khoshbouei, 2018; Sambo et al., 2017). In addition, both COC and METH appear to act as σ1R agonist and interact with σ1R at physiologically relevant concentrations (Kaushal & R. Matsumoto, 2011; Matsumoto, Nguyen, Kaushal, & Robson, 2014; Sharkey, Glen, Wolfe, & Kuhar, 1988). However, since no crystal structures of σ1R bound to COC or METH are available, it remains unclear if these psychostimulants display the same mode of action as those typical agonists or antagonists shown in the crystal structures. Moreover, the molecular basis of the coupling of ligand binding and protein-protein interactions remains elusive. Specifically, how the interactions between DAT and σ1R affect the interactions between σ1R and METH, as well as interactions between DAT and METH.

In this study, we constructed structural models of σ1R bound to diverse ligands including METH, COC, pentazocine, and haloperidol in order to investigate their binding modes, binding affinities, and the effects of ligand binding on the dynamics of σ1R. We showed that METH exhibited the lowest binding affinity among the ligands examined, and was more likely to act as a σ1R agonist that biases the receptor toward monomers. The structural models of dDAT in complex with the truncated σ1R were constructed in order to explore the potential binding interfaces between these two transmembrane proteins. Two models of dDAT in complex with the truncated σ1R were obtained in which σ1R could interact with either the helix α12 or α5 of dDAT. The structural models of dDAT bound to the full-length σ1R were then constructed in order to elucidate the coupling effects of protein-protein binding on the protein-ligand binding. We found that the binding of the truncated σ1R to dDAT was stronger than the binding of the full-length σ1R to dDAT. Interactions of σ1R with different helices of dDAT resulted in distinct dynamics of both proteins, but invariably attenuated the binding affinity of METH to dDAT, especially when interacting with the helix α5 of dDAT. The predicted binding affinity confirmed that the association of dDAT with σ1R could be achieved via distinct helix-helix interactions, providing structural insights into the role of protein binding interfaces on the regulation of METH-induced effects.

2. METHOD

2.1. Modeling and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of protein-ligand complexes

The X-ray crystal structure of dDAT bound to METH (PDB ID: 4XP6) was used to construct the wild-type structure of dDAT (K. H. Wang et al., 2015). The detailed protocol can be found in our previous study of dDAT in complex with DA and COC (Xu & Chen, 2020). Briefly, the flexible loop region containing residues Ser162‒Val202, which is not resolved in the crystal structure, was modelled and optimized using MODELLER program (version 9.23) (Webb & Sali, 2016). The mutated residues in the crystal structure were reverted to the wild-type amino acids. The two sodium ions (Na+), one chloride (Cl−) ion, and water molecules found in the crystal structure were kept in the final modeled structure. The structure of METH is positively charged in the quaternary ammonium motif (Berfield, Wang, & Reith, 1999).

The METH-bound dDAT structure was embedded into a mixed lipid bilayer consisting of total 360 lipids (POPC:POPE:POPG:CHOL = 3:1:1:1) (Nielsen et al., 2019; Xu & Chen, 2020). The orientation of the dDAT structure relative to the membrane was defined by aligning to the dDAT structure in the Orientation of Protein in Membrane database (PDB ID: 4M48) (Lomize, Pogozheva, Joo, Mosberg, & Lomize, 2012). The complex was then solvated by adding a 20 Å thick water layer (TIP3P water molecules) below and above the lipid bilayer, and 0.15 M NaCl was added to the system. The protein and lipid structures were represented with the CHARMM36m and CHARMM36 force field parameters, respectively (Huang et al., 2016; Klauda et al., 2010). The CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) was used to generate the topology and force field parameters for the structure of METH (Vanommeslaeghe et al., 2009), with the partial charges replaced with the calculated RESP charges (Figure S1, supplementary material) (J. Wang, Cieplak, & Kollman, 2000). The CHARMM-GUI web server was used to generate the starting structures and configuration files for MD simulations (Jo, Kim, Iyer, & Im, 2008; J. Lee et al., 2015).

MD simulations were carried out using GROMACS simulation package (version 2019.4) (Abraham et al., 2015; Berendsen, van der Spoel, & van Drunen, 1995; Kutzner et al., 2019). Each system was first energy minimized for 10,000 steps, followed by six stages of equilibration with the harmonic constraints exerted on lipid, protein and ligand heavy atoms. The force constants for lipid head group was decreased from 1000 kJ/(mol·nm2) to 40 kJ/(mol·nm2) until 0 kJ/(mol·nm2), whereas the force constants for protein backbone and sidechain (denoted as backbone/sidechain) were gradually decreased from 4000/2000 kJ/(mol·nm2) to 50/0 kJ/(mol·nm2) during the equilibration procedures. The temperature was kept constant at 303 K using the Berendsen thermostat with a coupling parameter of 0.1 ps (Berendsen, Postma, van Gunsteren, DiNola, & Haak, 1984), and the pressure was controlled at 1.0 bar using the Berendsen barostat with a time constant 5.0 ps for the last four stages of equilibration (Berendsen et al., 1984). The semiisotropic pressure coupling was applied for membrane simulations. A cutoff of 12 Å was applied for the van der Waals interactions and the long-range electrostatic interactions were treated using the particle mesh Ewald method (Darden, York, & Pedersen, 1993). The integration time step was 2 fs and trajectory was saved every 10 ps. The production dynamics were performed at the constant temperature (303 K) controlled by the Nosé-Hoover thermostat (Hoover, 1985; Nosé, 1984) and constant pressure (1.0 bar) controlled by the Parrinello-Rahman (Parrinello & Rahman, 1980, 1981) barostat without any restraints. The production simulations ran for 500 ns and the last 50-ns trajectory of each system was used for analysis.

To model the METH-bound σ1R, one monomer taken from the crystal structure of human σ1R bound to PD144418 (PDB ID: 5HK1) (Schmidt et al., 2016) was used for molecular docking and subsequent simulations. Since this crystal structure is a homotrimer, the chain B containing residues 1–219 was used to construct the structural model of σ1R containing residues 1–220. The residue Gly220 was added after alignment of chain B with chain C which contains residues 2–220. In the structure of σ1R, Glu172 was charged to interact with the ligand, and Asp126 was protonated to form a hydrogen bond with Glu172 (Schmidt, Betz, Dror, & Kruse, 2018; Schmidt et al., 2016). Autodock 4.2 program (Morris et al., 2009) was applied to dock METH molecule into the ligand binding site of σ1R. The σ1R structure was represented with the CHARMM36m force field parameters (Huang et al., 2016), and the METH structure was represented with the CGenFF (Vanommeslaeghe et al., 2009) along with the RESP partial charges (Figure S1). In the docking process, the σ1R structure was modeled as rigid while the METH structure was modeled as flexible. Lamarckian genetic algorithm (Morris et al., 2009) was applied to search the potential ligand binding pose in the binding site. The optimal ligand conformer was selected based on the following criteria: (1) the N atom in the quaternary ammonium motif should be able to form a salt-bridge with the residue Glu172 as observed in the crystal structures of σ1R bound to various ligands; (2) the docked conformer should have a relatively low binding energy according to the docking scoring functions; and (3) the docked conformer should have a relatively high probability of occupying the same binding site. For comparison, docking study was also performed to search the binding pose of COC in the binding pocket of σ1R.

The structure of σ1R bound to METH was inserted into a mixed lipid bilayer consisting of 360 lipids (POPC:POPE:POPG:CHOL = 3:1:1:1) (Nielsen et al., 2019; Xu & Chen, 2020). The orientation of σ1R relative to the membrane was aligned based on the same σ1R structure in the Orientation of Protein in Membrane database (PDB ID: 5HK1). The system was then solvated and added 0.15 M NaCl using the same protocol as modeling METH-bound dDAT. MD simulations followed the same procedures as applied for the above dDAT bound to METH. For comparison, MD simulations of σ1R bound to the typical agonist pentazocine (PDB ID: 6DK1) and the antagonist haloperidol (PDB ID: 6DJZ) were also performed, with the initial ligand-bound conformations taken from the crystal structures (Schmidt et al., 2018).

2.2. Modeling and MD simulations of protein-protein complexes

In order to construct the complex of dDAT-σ1R, the truncated form of σ1R containing residues 1–102 was used to explore the potential binding interface between dDAT and σ1R. The GRAMM-X web server (Andrei Tovchigrechko & Vakser, 2005; A. Tovchigrechko & Vakser, 2006) developed for protein–protein docking was used to generate dDAT-σ1R models. The following criteria were then applied to evaluate the top 10 candidates: (1) the transmembrane helical region of truncated σ1R (residues 1–32) should be positioned inside the membrane; (2) the remaining part of truncated σ1R (residues 33–102) should be in the intracellular side; and (3) the full-length σ1R modeled by adding residues 103–223 to the truncated σ1R should avoid bad steric contacts with dDAT. As a result, two dDAT-σ1R complexes in which σ1R bound to different interfaces of dDAT were selected for further simulation studies. The structure of dDAT associated with the full-length σ1R was constructed by aligning the truncated σ1R bound to dDAT with the full-length σ1R. Thus, two models of dDAT associated with the full-length σ1R were obtained. MD simulations of dDAT-σ1R complex followed the same protocol as used to simulate dDAT in complex with METH and σ1R in complex with METH. To insert the structure of dDAT in complex with the full-length σ1R, a larger mixed lipid bilayer containing 552 lipids was generated using the CHARMM-GUI web server (Jo et al., 2008).

2.3. Dynamic cross-correlation map (DCCM)

The effects of protein-protein interactions on the conformational dynamics were characterized in terms of the cross-correlated network analyses of Cα atomic fluctuations using the R package Bio3D (Grant, Rodrigues, ElSawy, McCammon, & Caves, 2006; Skjærven, Yao, Scarabelli, & Grant, 2014). The conformations were taken at every 100 ps interval from the entire trajectory and a covariance matrix was calculated between residues i and j using the following equation:

| (1) |

where Δri and Δrj are the displacement of the ith and jth residue from their mean position with respect to the time interval. Positive Cij values correspond to Cα motions between residues i and j are in the same direction along a give spatial coordinate; and negative Cij values correspond to Cα motions between residues i and j are in opposite direction along a give spatial coordinate.

The overlap between two conformational spaces was measured by the root mean square inner product (RMSIP) according to

| (2) |

where pi and qj are the ith and jth eigenvectors in one subspace and the other subspace, respectively (Amadei, Ceruso, & Di Nola, 1999). In this work, the RMSIP values were calculated on the first 20 eigenvectors obtained from a principal component analysis of the Cα covariance matrix of the atomic positional fluctuations.

2.4. Evaluation of protein stability, protein-ligand binding affinity, and protein-protein binding affinity

The relatively stability of different proteins were further quantitatively evaluated by the conformational energy, which was calculated using the generalized Born using molecular volume (GBMV) implicit solvent model implemented in the CHARMM (v44b1) program (Brooks et al., 2009). The single point energy was calculated after a 200-step minimization of each conformation using the GBMV II algorithm (Feig et al., 2004; M. S. Lee, Salsbury, & Brooks, 2002). Other energy terms including bonded energy, van der Waals energy, electrostatic energy, and solvation energy were also obtained with the GB implicit solvent model. The block average method was used to estimate the mean values and standard deviations.

The binding free energy of METH to dDAT and METH to σ1R was calculated using the g_mmpbsa program (Kumari, Kumar, & Lynn, 2014) which implements the molecular mechanics Poisson–Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA) method (P. Kollman, 1993; P. A. Kollman et al., 2000) to predict the binding affinity for protein-ligand complex. The entropy contribution was not included in the current binding energy calculations. The mean values and standard deviations were calculated in terms of the block average method.

In the classical MM-PBSA method, a uniform dielectric constant was used to calculate the solvation free energy, which seemed not applicable for calculating the binding affinity between dDAT and σ1R as both proteins are transmembrane proteins, especially the two domains of σ1R are separately in the membrane and cytosol. Here, we applied a method that is based on the inter-residue contacts and non-interacting surfaces to predict the absolute binding energy ΔG according to the linear equation below (Vangone & Bonvin, 2015):

| (3) |

where ICs denotes the number of inter-residue contacts; and %NIS denotes the percentage of non-interacting surface. Polar residues include Cys, His, Asn, Gln, Ser, Thr, Tyr, and Trp; apolar residues include Ala, Phe, Gly, Ile, Leu, Val, Met, and Pro; and charged residues include Glu, Asp, Lys, and Arg. In this contact-based method, two residues are considered in contact if any atom of one residue in dDAT is within a defined cut-off distance of any atom of one residue in σ1R. The distance threshold of 5.5 Å was found to obtain the best predictive model (Vangone & Bonvin, 2015).

3. RESULTS

3.1. METH showed a low binding affinity to σ1R and a binding pose different from other ligands.

The relative stability of dDAT (including two bound Na+ and one Cl− in the central binding pocket), σ1R, and dDAT-σ1R complex was evaluated by the root-mean-square deviations (RMSDs, Figures S2 and S3). In the absence of dDAT, the ligand-binding region of σ1R was relatively stable whereas the transmembrane helix of σ1R seemed more flexible (Figure S2). Upon association with dDAT, the transmembrane helix of σ1R became relatively stable due to interactions with dDAT (Figure S3).

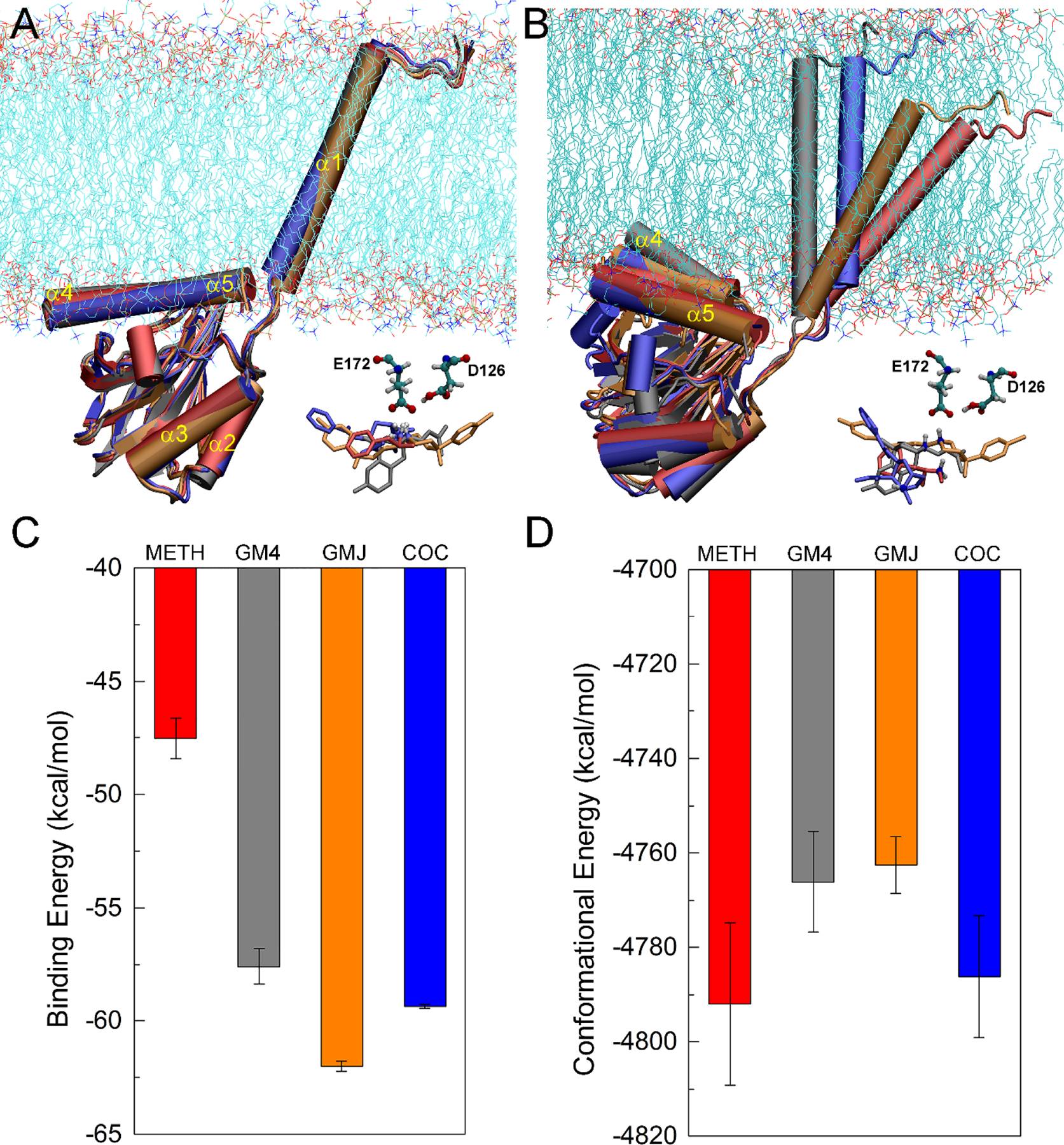

The initial poses of ligands in the binding pocket of σ1R overlapped after alignment of protein structures (Figure 1A). The binding orientations of METH and COC were consistent with recent molecular docking and pharmacological studies of σ1R ligands, suggesting that Glu172 interacted with the positively charged group of the σ1R ligand (Peng, Dong, & Welsh, 2018; Yano et al., 2018), and the aromatic ring of different ligands interacted with Tyr103 (Peng et al., 2018; Rossino et al., 2019). The distance between the N atom of the quaternary ammonium motif of each ligand and the Cδ atom of Glu172 was 3.1 Å, 3.2 Å, 3.6 Å, and 4.2 Å for σ1R bound to METH, pentazocine (denoted as GM4, agonist), haloperidol (denoted as GMJ, antagonist), and COC, respectively. After 500-ns simulations, these corresponding distances became 3.8±0.0 Å, 3.4±0.0 Å, 3.3±0.0 Å, and 9.2±0.0 Å (block averaged over the last 50-ns simulations), suggesting that the salt-bridge was maintained for σ1R bound to METH, GM4 and GMJ, but not for COC (Figure 1B). The calculated binding energy implied that METH had the lowest binding affinity to σ1R among the ligands investigated here (Figure 1C). The finding that COC had a relatively higher binding affinity than METH, but could not form a stable salt-bridge with Glu172 indicated that METH may exhibit a different mode of action from COC with respect to σ1R. The antagonist GMJ displayed the highest binding affinity to σ1R, which seemed in line with experimental findings that high-affinity and selective σ1 antagonists could be used to attenuate METH-induced stimulant and neurotoxic effects (Kaushal et al., 2011; Matsumoto, Shaikh, Wilson, Vedam, & Coop, 2008; Tapia et al., 2019). It is well recognized that σ1R can accommodate diverse ligands (Yano et al., 2018), however, the binding of different ligands yielded different effects on σ1R conformations. Note that the σ1R agonists could lead to monomeric or low-molecular-weight σ1R species, but the antagonists stabilize high-molecular-weight species (Gromek et al., 2014; Mishra et al., 2015; Yano et al., 2018). The calculated conformational energy of σ1R in complex with different ligands showed that the binding of METH or COC resulted in more stable conformations of σ1R (Figure 1D), in line with their agonist function. The comparative stability in the conformations of σ1R induced by GM4 and GMJ may obscure the biochemical difference between agonists and antagonists. Such results may indicate that σ1R could sample a conformational ensemble of different states, and the structural features that determine the preference of σ1R existing in the monomeric or oligomeric state maybe related to specific structural alterations induced by ligands bound to σ1R.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Initial conformations of σ1R bound to METH (red), GM4 (agonist, gray), GMJ (antagonist, orange), and COC (blue), aligned with respect to the conformation of σ1R bound METH; (B) Representative conformations of σ1R bound to different ligands after 500-ns MD simulations; (C) The calculated binding energy for the binding of different ligand to σ1R; (D) The calculated conformational energy of σ1R bound to different ligands.

To elucidate the structural changes caused by the binding of different ligands to σ1R, the root-mean-square fluctuations (RMSFs) were calculated after alignment of the conformations of σ1R relative to the initial σ1R structure bound to METH (Figure S4). The transmembrane helix α1 was excluded for alignment as it adopted different orientations in the membrane (Figure 1B). This finding supported the role of α1 that it may act to tether the receptor to the membrane (Schmidt et al., 2016). In addition to α1, the notable fluctuations occurred on three turn structures involving α3 (residues 65–73) and two β-hairpins (residues 83–90 and 135–143) in particular (Figure S4). Because these structural fluctuations were less than 3 Å, a high conservation in the ligand-binding domain was expected. Examination of the specific ligand-receptor interactions in the binding pocket revealed that METH and COC occupied different regions of the binding pocket of σ1R compared to the classical agonist GM4 and antagonist GMJ (Figure 2). The present simulations well reproduced interactions between GM4/GMJ and σ1R as observed in the crystal structures (Schmidt et al., 2018). For σ1R bound to GM4, in addition to new interactions with Thr198 and Thr202 on α5, all the other ligand-receptor interactions were maintained throughout the simulations. Notably, α4 was observed to move toward the membrane and away from GM4 (Figure 1B and Figure 2B), consistent with the experimental results (Schmidt et al., 2018). For σ1R bound to GMJ, the interaction of Val84 and Trp89 with GMJ became rather weak, whereas new interactions with Thr202 and Tyr103 were established during the simulations. All the other interactions of GMJ with σ1R were maintained throughout the simulations. In particular, residues Ile178, Thr181, Leu182, and Ala185 on α4, and residues Thr202 and Tyr206 on α5 were consistent with the experimental finding that antagonists adopt a more linear pose, with the primary hydrophobic part pointing toward helices α4 and α5 (Schmidt et al., 2018). In contrast, for σ1R bound to METH, strong interactions involved a few residues including Trp89, Tyr103, Leu105, Glu172, Leu182, and Ala185, with a contact frequency >80%. And the remaining interacting residues showed a contact frequency between 50%–80%. In this regard, METH seemed to adopt a similar pose with the agonist GM4, implying that METH may act more like an agonist.

FIGURE 2.

Interactions of METH (A), GM4 (B), GMJ (C), and COC (D) with σ1R. The ligands are shown in CPK representations, and the interacting residues are shown in Licorice representations. Residues are colored based on their types: blue for basic, red for acidic, green for polar, and white for nonpolar residues. Non-interacting residues D126 and E172 are shown in thin Licorice representations. A contact occurs if any atom of the ligand is within 3 Å of any atom of protein residues, and only residues with a contact frequency > 50% over the last-50 ns MD simulations are shown.

The initial binding pose of COC was very similar to METH and GM4, but the interaction with Glu172 (salt-bridge) was not maintained although most interactions in the binding pocket were preserved over the simulations, which was probably due to the steric constraints of its structure. Different from other ligands studied here, COC predominantly interacted with hydrophobic residues in the binding pocket, which may account for its high binding affinity to σ1R. To further characterize the difference in the protein-ligand interactions, the interaction energies between different ligands and σ1R were calculated and shown in Figure S5. Note that although the energy values varied across different ligands, both METH and GM4 showed more favorable electrostatic interaction energy. In contrast, the antagonist GMJ displayed more favorable van der Waals interactions with σ1R, which was more pronounced for the interactions between COC and σ1R. Such results might also indicate that METH could share the same binding mechanism as GM4 but different from GMJ and COC. Taken together, the above results suggested that different σ1R agonists (METH and COC) might exert their functions through different mechanisms.

3.2. dDAT could associate with σ1R via distinct helix–helix interfaces.

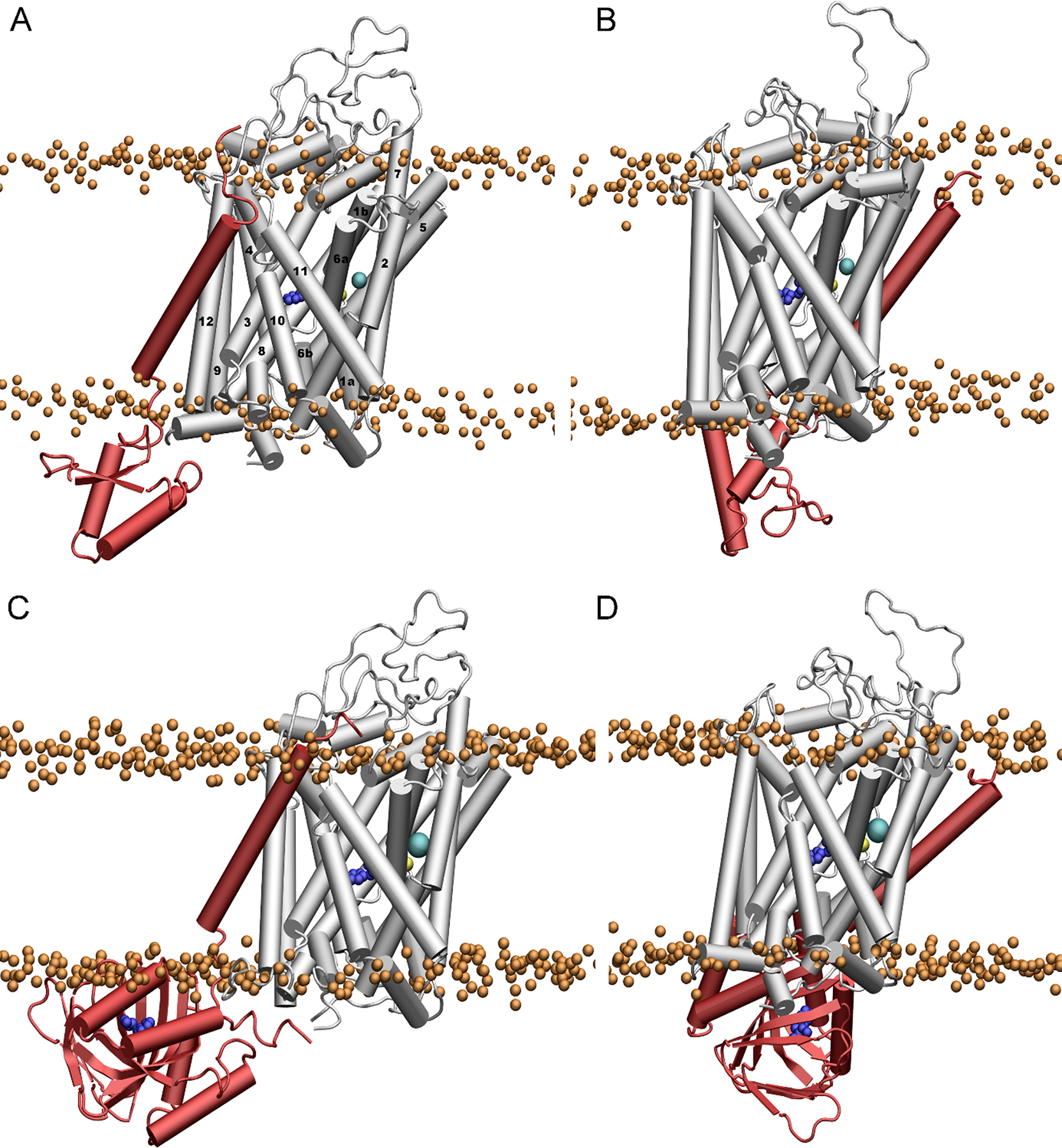

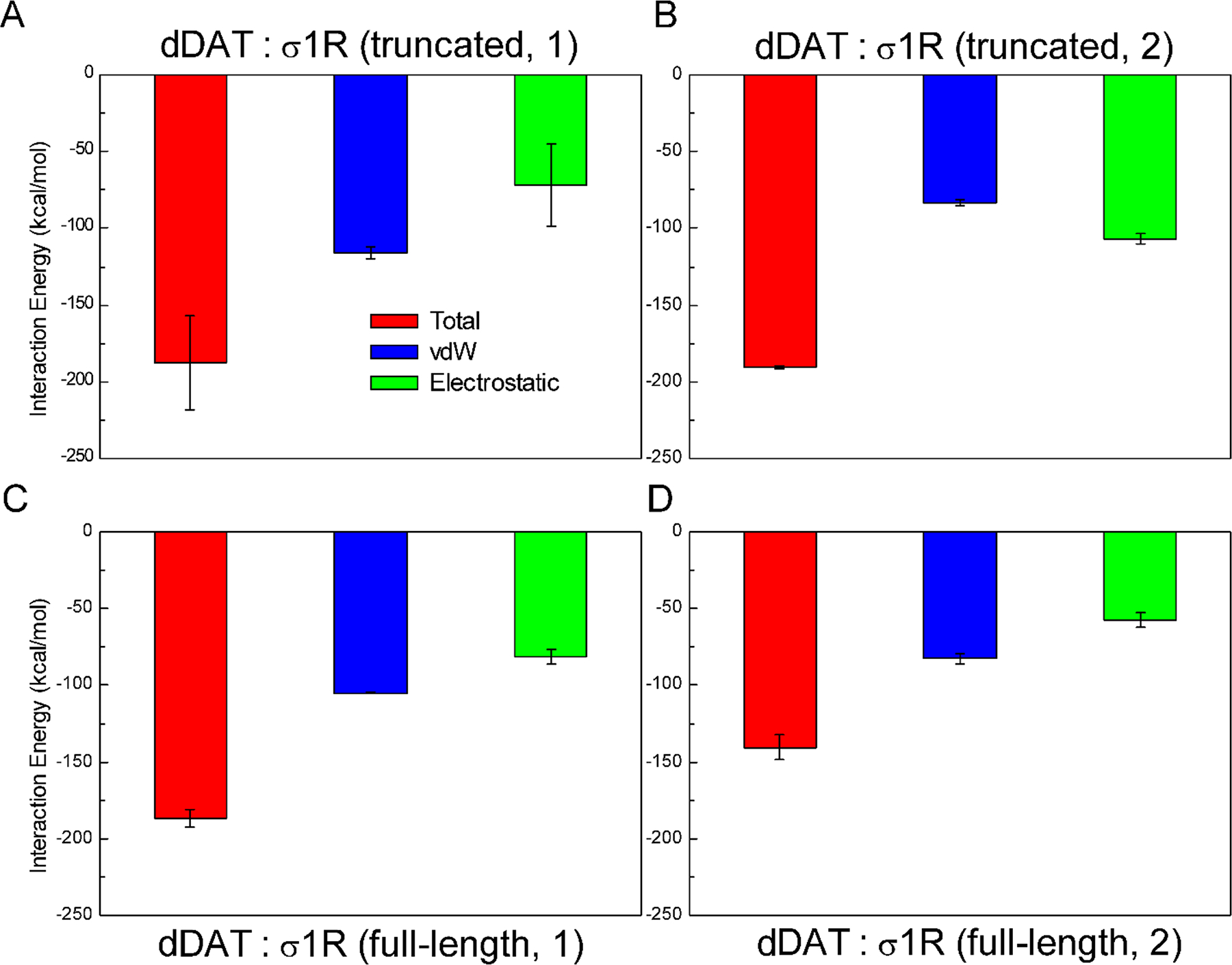

Two preferred dDAT-σ1R binding interfaces were identified by protein-protein docking analysis (Figure 3). The truncated σ1R consisting of residues 1–102 was used to perform the protein-protein docking because (1) it has fewer steric restraints to probe more potential binding interfaces on DAT; and (2) experimental results showed that this truncation exhibited stronger interactions with human DAT than the full-length σ1R (Hong et al., 2017). The present study predicted that σ1R could associate with dDAT through interactions with either the transmembrane helix α12 or α5 (Figure 3), and such helix-helix interactions involved both hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions (Figure 4). The calculated interaction energies between the truncated σ1R and dDAT showed that these two associations display comparably strong interactions (Figure 4A and 4B). When σ1R associated with the helix α12 of dDAT, the van der Waals interactions were more prominent than the electrostatic interactions, whereas in the association of σ1R with the helix α5 of dDAT, the electrostatic interactions were more pronounced than the van der Waals interactions. This finding suggested that dDAT may use different and independent interfaces to recognize and bind σ1R.

FIGURE 3.

Representative binding conformations of dDAT with the truncated σ1R (residues 1–102) (A, B), and the full-length σ1R (C, D). The structure of σ1R is shown in red, and the molecule of METH in the binding pocket is shown in blue. The bound Na+ and Cl− ions in dDAT are shown in yellow and cyan, respectively. The phosphate atoms of the lipid heads are shown as orange spheres to indicate the boundary of the membrane.

FIGURE 4.

Interaction energies calculated for the association of dDAT with the truncated σ1R (A, B), and the full-length σ1R (C, D). (truncated, 1) corresponds to the truncated σ1R bound to the helix α12 of dDAT (Figure 3A); (truncated, 2) corresponds to the truncated σ1R bound to the helix α5 of dDAT (Figure 3B); (full-length, 1) corresponds to the full-length σ1R bound to the helix α12 of dDAT (Figure 3C); and (full-length, 2) corresponds to the full-length σ1R bound to the helix α5 of dDAT (Figure 3D).

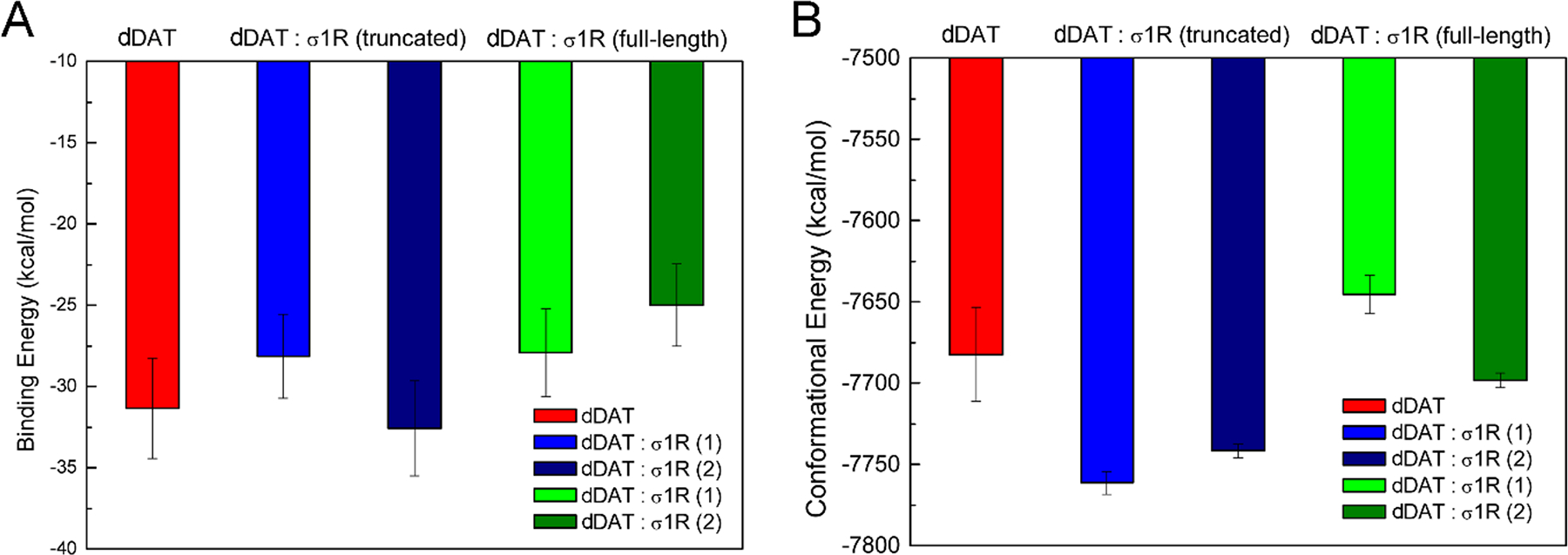

These two types of helix-helix interactions consistently stabilized the conformations of dDAT bound to METH (Figure 5), indicating that both binding interfaces appeared favorable for association of σ1R. Furthermore, these two different protein-protein interactions differently changed the binding affinity of METH to dDAT (Figure 5). The interactions of σ1R with helix α12 caused an increase (10%) in the binding energy of METH to dDAT, and therefore a reduced binding affinity; whereas the interactions with helix α5 led to a slightly (4%) lower binding energy of METH to dDAT. Taken together, the present results indicated that the truncated σ1R could bind to chemically different interfaces of dDAT through specific helix-helix interactions.

FIGURE 5.

The binding energy (A) and conformational energy (B) calculated for the binding of METH to dDAT in different systems. σ1R(1) corresponds to σ1R bound to the helix α12 of dDAT (Figure 3A and 3C); and σ1R(2) corresponds to σ1R bound to the helix α5 of dDAT (Figure 3B and 3D).

3.3. Interactions of dDAT with σ1R attenuated the binding affinity of METH to dDAT.

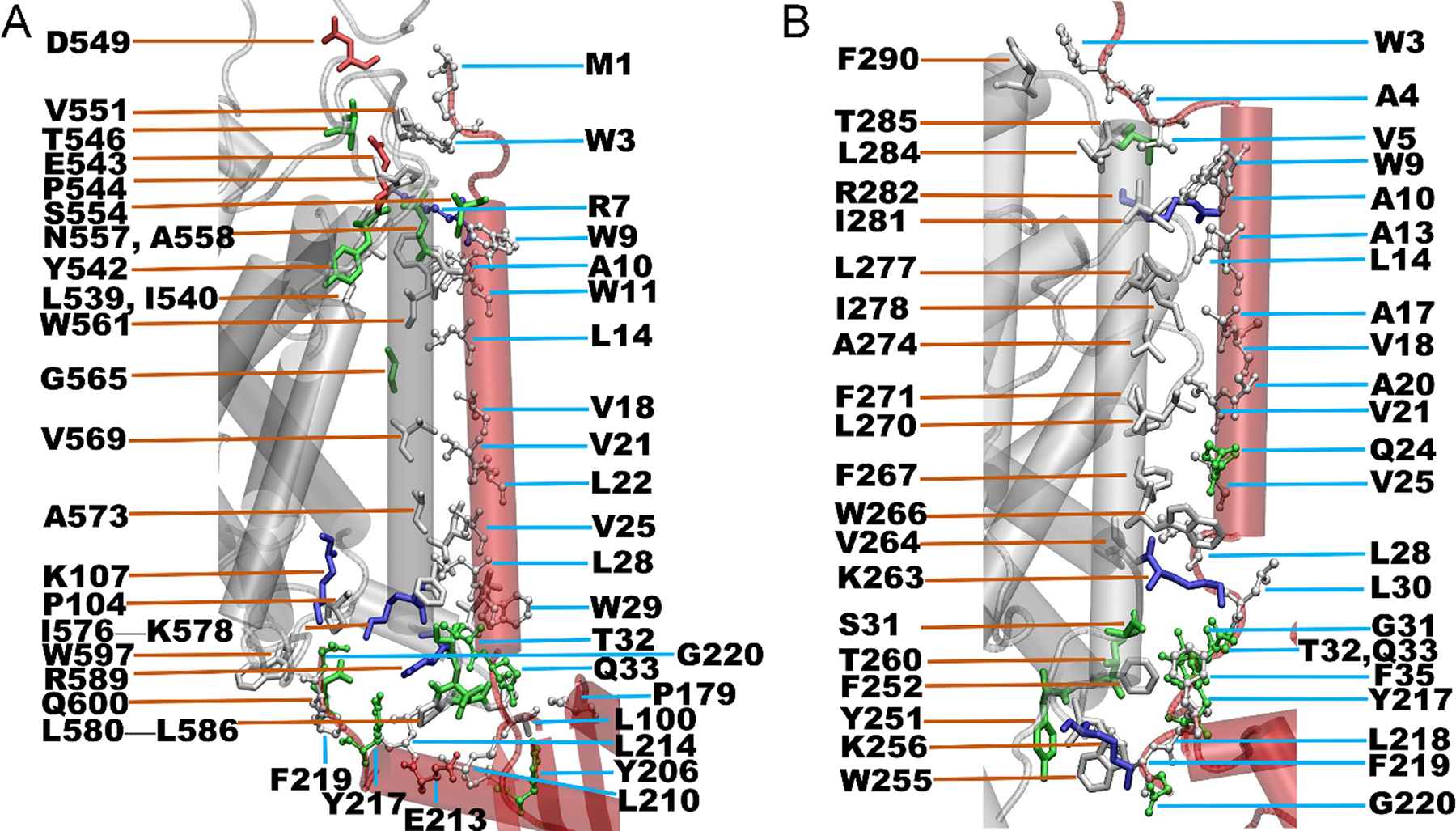

Based on the complexes of dDAT bound to the truncated σ1R, we constructed two complexes of dDAT in complex with the full-length σ1R, with the transmembrane helix of σ1R interacting with dDAT and the ligand-binding domain on the cytosolic side (Figure 3). After 500-ns simulations, in addition to the helix-helix interactions as observed in the systems of dDAT bound the truncated σ1R (Figure S6), the helix α12 of dDAT also interacted with residues on α4 and α5 of σ1R, including residues Pro179 on α4, and Tyr206, Ala207, Leu210, Glu213, Leu214, Tyr217 and Phe219 on α5 (Figure 6). Similarly, for the association of σ1R with the helix α5 of dDAT, interacting residues on α5 of σ1R (Tyr217, Leu218, Phe219 and Gly220) were also found (Figure 6). The involvement of helices α4 and α5 of σ1R in the interactions with dDAT seems expected as they are proximal to the membrane in the absence of a binding partner (Figure 3A).

FIGURE 6.

Helix-helix interactions between dDAT and the full-length σ1R. (A) Interactions of σ1R with the helix α12 of dDAT; and (B) Interactions of σ1R with the helix α5 of dDAT. The interacting parts of σ1R and dDAT are shown in red and white cartoon, respectively. Residues are colored based on their types: blue for basic, red for acidic, green for polar, and white for nonpolar residues. Two residues are considered in contact if a pair of (any) atoms belonging to two residues is closer than 3.0 Å, and only residues with a contact frequency > 50% over the last-50 ns MD simulations are shown.

To further identify the key interacting residues that could contribute to the association of σ1R and the full-length dDAT, we summarized the details of interactions between residues of σ1R and dDAT in Tables S1 and S2. It appeared that hydrophobic interactions were the primary driving force for the association of σ1R with dDAT. For instance, if σ1R bound to the α12 of dDAT (Figure 6A and Table S1), the involved hydrophobic residues included Leu539, Ile540, Pro544, Val551, Trp561, Val569, Ile576, Phe577, Leu580, Pro583, Leu586, and Trp597 in the α12 of dDAT, and Trp3, Trp9, Trp11, Leu14, Val18, Val21, Leu22, Val25, Trp29, Leu100, Pro179, Leu210, Leu214, and Phe219 in the σ1R. In particular, residues Trp561, Phe577, Pro583, and Leu586 of α12 interacted with at least three different residues of σ1R. And residues Trp9, Val25, Trp29, and Leu214 of σ1R were also found to interact with at least three different residues of dDAT. These residues might be the key residues for the association of σ1R with the α12 of dDAT. In addition, the electrostatic interactions between Glu543 of α12 and Arg7 of σ1R could also contribute to the binding of σ1R to dDAT. Similarly, if σ1R bound to the α5 of dDAT (Figure 6B and Table S2), five hydrophobic residues including Phe252, Phe267, Ile278, Ile281, and Leu284, and one charged residue Lys263 of the α5 of dDAT were found to interact with more than two different residues of σ1R. And four hydrophobic residues including Val5, Leu14, Leu28, and Phe219, and one polar residue Gln24 of σ1R were found to interact with three or more different residues of dDAT. Although there were common residues of σ1R identified on the binding surfaces (Figure 6), the difference in the interaction strength with the α12 or α5 of dDAT could lead to different binding affinities of helix-helix interactions.

Interestingly, compared to the interactions between dDAT and the truncated σ1R, the interaction strength was comparable for the interactions between the helix α12 of dDAT and the full-length σ1R (Figure 4C). The predicted binding energy was 13.24 kcal/mol (absolute value, Table 1) when associating the truncated σ1R with the helix α12 of dDAT; but a weaker binding affinity (11.15 kcal/mol) was predicted when associating the full-length σ1R. Of importance, the binding of the σ1R reduced the binding affinity of METH to dDAT (Figure 5). When interacting with the helix α12 of dDAT, an 11% decrease in the binding affinity was found, comparable to the binding of the truncated σ1R to helix α12 of dDAT. Hence, the present results imply that the binding of the full-length σ1R to dDAT lowered the binding affinity of METH to dDAT. On the other hand, the interactions with the helix α12 of dDAT slightly increased the binding affinity (4%) of METH to σ1R (Figure S7). Relative to the METH-bound dDAT, the interactions of the full-length σ1R with the helix α12 of dDAT destabilized the conformations of dDAT (~37 kcal/mol) (Figure 5). The changes in the conformational energies were of about the same magnitude of the fluctuations of the total conformational energies, suggesting that no significant conformational alterations of dDAT might be required for the association of σ1R. Also, relative to the METH-bound σ1R, the interactions with the helix α12 of dDAT led to comparably stable conformations of σ1R (Figure S7).

Table 1.

The binding affinity (absolute value) predicted using the contact-based method.

| System | ICs charged/charged |

ICs charged/apolar |

ICs polar/polar |

ICs polar/apolar |

%NIS apolar |

%NIS charged |

ΔG (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAT:σ1R (truncated, 1) |

1 | 8 | 13 | 37 | 34.14 | 22.17 | 13.24 |

| DAT:σ1R (truncated, 2) |

5 | 4 | 13 | 32 | 34.39 | 17.50 | 12.69 |

| DAT:σ1R (full-length, 1) |

1 | 16 | 17 | 25 | 33.67 | 18.37 | 11.15 |

| DAT:σ1R (full-length, 2) |

0 | 6 | 14 | 22 | 33.70 | 21.82 | 9.48 |

Note:

(1) (truncated, 1) denotes the truncated σ1R that binds to the helix α12 of dDAT; (truncated, 2) denotes the truncated σ1R that binds to the helix α5 of dDAT; (full-length, 1) denotes the full-length σ1R that binds to the helix α12 of dDAT; and (full-length, 2) denotes the full-length σ1R that binds to the helix α5 of dDAT.

(2) The inter-residue contacts were calculated using the last-50 ns trajectory of each simulation, and only contact frequency >50% was taken into account. The distance cut-off 5.5 Å was used to define a contact.

For the binding of σ1R with the helix α5 of dDAT, a decrease of 12% in the interaction energy was observed for the interactions between dDAT and the full-length σ1R when compared with the truncated σ1R (Figure 4D). Similarly, the predicted binding affinity for the association of dDAT with the truncated σ1R (12.69 kcal/mol) is lower than the association with the full-length σ1R (9.48 kcal/mol), suggesting that the association of dDAT with the full-length σ1R appeared weaker than the association with the truncated σ1R. The binding of σ1R to the helix α5 of dDAT resulted in more reduction (20%) in the binding affinity of METH to dDAT, further implying that the reduction in the binding affinity of METH to dDAT seemed independent of the binding interfaces between dDAT and σ1R. The association of these two proteins led to opposite effects on the binding affinity of METH to σ1R. A little decrease in the binding affinity (5%) of METH to σ1R was found when interacting with the helix α5 of dDAT (Figure S7). The interactions of the full-length σ1R with the helix α5 of dDAT slightly stabilized the conformations of dDAT (~16 kcal/mol) (Figure 5), but less stable conformations of σ1R were observed (Figure S7). Further examination of the structural changes of σ1R identified the disruption of the hydrogen bonds between the highly conserved Glu102 and backbone residue Val36 (Figure S8). These hydrogen bonds were well or largely maintained for the conformations of σ1R bound to METH or the complex in which σ1R bound to the helix α12 of dDAT (Figure S8). Previous study suggested that E102Q may destroy such favorable hydrogen-bond interactions and consequently destabilize σ1R (Schmidt et al., 2016). A recent study also implied that E22 mutants (E22Q and E22A) had little impact on the ligand-binding domain but disrupted the interactions between E102 and the loop connecting the N-terminal transmembrane helix and C-terminal domain, and may destabilize σ1R oligomers (Abramyan et al., 2020). The present results suggest that the interactions of σ1R with the helix α5 of dDAT could induce σ1R destabilization through the same molecular mechanism by perturbing the connection between the transmembrane and cytosolic domains (Figure S8).

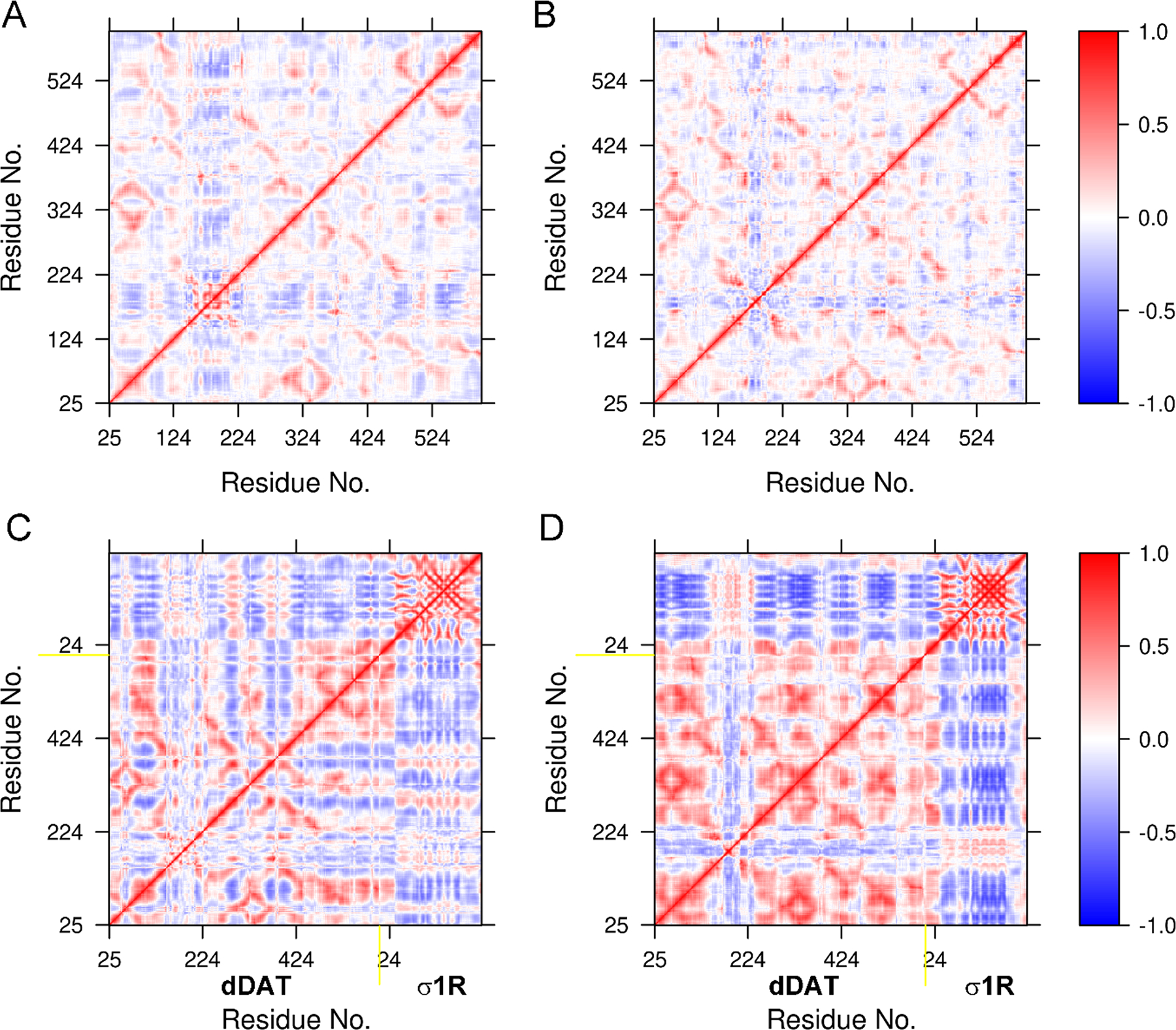

Figure 7 showed the DCCMs of dDAT bound to the truncated σ1R (Figure 7A, B), as well as the full-length σ1R (Figure 7C, D). The high similarity in the DCCMs of dDAT bound to the truncated σ1R using different helices indicated that interactions with the truncated σ1R could influence the dynamics of dDAT in the same way. However, more anti-correlations were found for the extracellular loop including residues 160–200 when dDAT bound to the truncated σ1R with the helix α12 (Figure 7A), suggesting more flexibility induced by such interactions. In contrast, the apparent difference in the DCCMs of dDAT bound to the full-length σ1R showed that the influence of association of dDAT with σ1R on the dynamics of individual binding partner was dependent on the interacting interfaces. More positive correlations were detected for the conformations of dDAT bound to σ1R through its helix α5, compared to the interactions with the helix α12 (Figure 7C, D). Also, from the DCCM of dDAT bound to σ1R through its helix α5 (Figure 7D), more anti-correlations were detected for the dynamics of σ1R, suggesting distinct effects of the association of dDAT on the conformational dynamics of σ1R. The RMSIP values were further calculated to quantitatively measure the overlap of the correlated motions between two conformational assembles. A RMSIP value of 0 suggests no correlation between two subspaces and a value of 1 implies identical subspaces (full correlation). A value between 0.5 to 0.7 is considered fairly to excellently correlated subspaces (David & Jacobs, 2011). The calculated RMSIP values between any two σ1R systems varied between 0.58 and 0.68 (Table S3), indicating notable similarity in the conformational spaces sampled by σ1R bound to different ligands or associated with dDAT. In addition, a fairly correlated conformational motions (RMSIP = 0.53) were found between dDAT in complex with σ1R using either helix α12 or α5, suggesting more distinct effects of the association of σ1R on the conformational dynamics of dDAT.

FIGURE 7.

Dynamic cross-correlation maps (DCCMs) constructed for dDAT bound to the truncated σ1R (A, B), and the full-length σ1R (C, D). The DCCMs for the truncated σ1R are not shown in A and B.

4. DISCUSSION

The psychostimulant METH can bind to both DAT and σ1R. The binding of METH to DAT disrupts DA transport by DAT and enhances the synaptic concentration of DA consequently (Goodwin et al., 2009). Based on our simulation studies, METH was predicted to have a higher binding affinity to dDAT compared to COC and DA (Figure S9). The binding of METH to σ1R could lead to locomotor stimulatory effects, highlighting the important role of σ1R in mediating the actions of a number of psychomotor stimulants such as METH (E. C. Nguyen, McCracken, Liu, Pouw, & Matsumoto, 2005; Sambo et al., 2018). The present work showed that METH displayed a lower binding affinity to σ1R compared to COC and classical agonist and antagonist. The finding that the antagonist haloperidol (GMJ) had a much higher binding affinity to σ1R explained why many σ1R antagonists can attenuate METH-induced effects, although the underlying molecular mechanism on the neuroprotective effects of σ1R antagonists remains to be elucidated (Kaushal, Seminerio, Robson, McCurdy, & Matsumoto, 2013; Kaushal et al., 2011; Matsumoto et al., 2008; E. C. Nguyen et al., 2005). Because the crystal structures of σ1R in complex with different ligands were trimers (Schmidt et al., 2018; Schmidt et al., 2016), to confirm the relative binding affinity of ligands to σ1R, the trimeric σ1R in complex with different ligands (METH, GM4, GMJ, and COC) were also simulated using the same simulation protocols. The relative binding affinity of these four ligands with respect to σ1R did not change (Figure S10), suggesting that the binding strength of these ligand was independent of the σ1R state. The experimental evidence that upon activation σ1R can interact with DAT and mediate multiple COC- or METH-stimulated effects (Hong et al., 2017; Sambo et al., 2017) provides clues to the investigation of the binding pattern between the two transmembrane targets of METH, which involves protein-ligand interactions, protein-protein interactions, and the coupling of both interactions.

The present results are in agreement with the experimental finding that chemically dissimilar ligands occupy different positions in the ligand-binding pocket of σ1R (Schmidt et al., 2018; Schmidt et al., 2016). We showed that the binding environment of METH was more similar to the agonist COC, but COC interacted with more hydrophobic residues (Figure 2). These diverse ligand binding modes inevitably resulted in distinct dynamics of σ1R as characterized by their DCCMs (Figure S11) and conformational stabilities (Figure 1). And any subtle conformational changes could alter the oligomer interface of σ1R, either stabilizing (antagonists) or destabilizing (agonists) the formation of σ1R oligomers. The crystal structures of σ1R bound to a diversity of ligands showed a homotrimeric assembly with the trimerization interface packed by the ligand-binding domains (Schmidt et al., 2018; Schmidt et al., 2016). However, σ1R oligomers larger than trimers were also identified experimentally (Hong et al., 2017), indicating alternative oligomer interfaces that are functionally relevant. For instance, the σ1R assembly formed by the transmembrane helix-helix interactions was proposed in a recent study (Abramyan et al., 2020). The present study suggests that the binding of a specific ligand could trigger different dynamics of σ1R, and consequently affect the formation of σ1R oligomers.

Base on the protein-protein docking protocols and the required orientation of σ1R with respect to the membrane and solution, two binding modes in which the transmembrane helix of σ1R interacts with either the helix α12 or α5 of dDAT were identified. The calculated interaction energy (Figure 4) and the predicted binding affinity (Table 1) consistently suggested that these two associations exhibited comparable binding strength. We found that the binding of the truncated σ1R to dDAT stabilized the conformations of dDAT in complex with METH, but slightly changed the binding affinity of METH to dDAT (Figure 5). The calculated interaction energy (Figure 4) and the predicted binding affinity (Table 1) indicated that the interactions of σ1R with the helix α5 of dDAT reduced the binding affinity between the two proteins more notably. Both association patterns attenuated the binding affinity of METH to dDAT (Figure 5) but exhibited opposite effects on the binding of METH to σ1R (Figure S7). And the interactions of σ1R with the helix α5 of dDAT significantly destabilized the conformations of σ1R (Figure S7), probably due to the disruption of the hydrogen-bond interactions between Glu102 and Val36 (Figure S8). This finding implied that the binding of σ1R to the helix α5 of dDAT may induce large conformational change for σ1R but could still retain dDAT in the outward-open state (Figure S12). The predicted binding affinities (absolute values) were 11.15 kcal/mol and 9.48 kcal/mol, respectively, corresponding to the binding affinities of various protein-protein associations with crystal structures available (Vangone & Bonvin, 2015). For instance, the leukemia inhibitory factor in complex with gp130 (PDB ID: 1PVH) showed a comparable binding affinity of 9.5 kcal/mol (Boulanger, Bankovich, Kortemme, Baker, & Garcia, 2003) with one of our models. Based on these findings, we propose that σ1R could associate with dDAT through different interactions with either the helix α12 or α5 of dDAT, and mitigate the binding affinity of METH to dDAT to different levels, in line with the experiment data showing that interactions of σ1R with DAT decreased METH-induced stimulatory effects (Sambo et al., 2017). In addition, the transmembrane helix α12 seems also involved in the dimerization interface of dopamine and leucine transporters (Krishnamurthy & Gouaux, 2012; Xu & Chen, 2020), suggesting that the helix α12 of DAT might be a conserved binding site responsible for protein-protein interactions.

The experimental finding suggested that the truncated σ1R displayed a higher binding strength to human DAT (hDAT) than the full-length σ1R (Hong et al., 2017). The sequence identity between dDAT and hDAT is about 52% (Figure S13), and because no crystal structure of hDAT is available to date, the crystal structures of dDAT in complex with diverse substrates provide ideal templates to construct the structures of hDAT, human serotonin transporter, and norepinephrine transporter using homology modeling approaches. These structural models have been applied to investigate the binding mechanism of the drugs for the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (P. Wang, Fu, et al., 2017; P. Wang, Zhang, et al., 2017), and the drugs for the treatment of depression and other behavioral disorders (Xue et al., 2020; Xue et al., 2018). These studies suggested a quite similar central ligand binding pocket between dDAT and hDAT. Because METH and COC bind to the same binding pocket of dDAT, it seems reasonable to assume that METH and COC may share the same binding mechanism between dDAT and hDAT. For hDAT, F154A mutant was found to lower the binding affinity of COC (Lin & Uhl, 2002), and the corresponding F122A in dDAT was also suggested to allosterically decrease the binding affinity of COC in our recent studies, suggesting that the mutation effect on the binding of COC could be the same between dDAT and hDAT (Xu & Chen, 2020). Moreover, the NSS proteins share a conserved fold, but their sequence identity varies significantly (Cheng & Bahar, 2019). For instance, the bacterial leucine transporter (LeuT) shows only about 23% sequence identity to hDAT, but a general alternating access mechanism was proposed for the NSS to transport substrate between the extracellular and intracellular sides of the membrane by switching the transporter conformation between the outward-open and inward-open state (Forrest et al., 2008). This general mechanism for the substrate transporting implied that concerted domain motions in DAT seemed more important than the specific pair residue interactions in regulating the binding and release of DAT substrates. Therefore, the present results could also have implications for the interactions between hDAT and σ1R, implying that hDAT could associate with σ1R in a similar manner as dDAT did. Taken together, our study provides detailed molecular insights into the interactions between DAT and σ1R, and how these interactions mediate the binding of METH to DAT and to σ1R as well. Our results highlight the distinct roles of transmembrane helices α12 and α5 of DAT in the association of σ1R, suggesting new functionally relevant sites for regulating METH-induced physiological effects.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the support from the NIH (grant #GM121275), and the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC) at The University of Texas at Austin for providing HPC resources that have contributed to the research results reported within this paper.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- Abraham MJ, Murtola T, Schulz R, Páll S, Smith JC, Hess B, & Lindahl E (2015). Gromacs: High Performance Molecular Simulations through Multi-Level Parallelism from Laptops to Supercomputers. SoftwareX, 1–2, 19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.softx.2015.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abramyan AM, Yano H, Xu M, Liu L, Naing S, Fant AD, & Shi L (2020). The Glu102 Mutation Disrupts Higher-Order Oligomerization of the Sigma 1 Receptor. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal, 18, 199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2019.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amadei A, Ceruso MA, & Di Nola A (1999). On the Convergence of the Conformational Coordinates Basis Set Obtained by the Essential Dynamics Analysis of Proteins’ Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Genetics, 36, 419–424. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, van Gunsteren WF, DiNola A, & Haak JR (1984). Molecular Dynamics with Coupling to an External Bath. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 81, 3684–3690. doi: 10.1063/1.448118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen HJC, van der Spoel D, & van Drunen R (1995). Gromacs: A Message-Passing Parallel Molecular Dynamics Implementation. Computer Physics Communications, 91, 43–56. doi: 10.1016/0010-4655(95)00042-e [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berfield JL, Wang LC, & Reith MEA (1999). Which Form of Dopamine Is the Substrate for the Human Dopamine Transporter: The Cationic or the Uncharged Species? Journal of Biological Chemistry, 274, 4876–4882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger MJ, Bankovich AJ, Kortemme T, Baker D, & Garcia KC (2003). Convergent Mechanisms for Recognition of Divergent Cytokines by the Shared Signaling Receptor Gp130. Molecular Cell, 12, 577–589. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00365-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks BR, Brooks CL, Mackerell AD, Nilsson L, Petrella RJ, Roux B, … Karplus M (2009). Charmm: The Biomolecular Simulation Program. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 30, 1545–1614. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchetti C, Pyle E, & Byrne B (2019). Transporter Oligomerisation: Roles in Structure and Function. Biochemical Society Transactions, 47, 433–440. doi: 10.1042/bst20180316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng MH, & Bahar I (2019). Monoamine Transporters: Structure, Intrinsic Dynamics and Allosteric Regulation. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 26, 545–556. doi: 10.1038/s41594-019-0253-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darden T, York D, & Pedersen L (1993). Particle Mesh Ewald: An N⋅Log(N) Method for Ewald Sums in Large Systems. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 98, 10089–10092. doi: 10.1063/1.464397 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- David CC, & Jacobs DJ (2011). Characterizing Protein Motions from Structure. Journal of Molecular Graphics and Modelling, 31, 41–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2011.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen J, Jørgensen TN, & Gether U (2010). Regulation of Dopamine Transporter Function by Protein-Protein Interactions: New Discoveries and Methodological Challenges. Journal of Neurochemistry, 113, 27–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06599.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feig M, Onufriev A, Lee MS, Im W, Case DA, & Brooks CL (2004). Performance Comparison of Generalized Born and Poisson Methods in the Calculation of Electrostatic Solvation Energies for Protein Structures. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 25, 265–284. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest LR, Zhang YW, Jacobs MT, Gesmonde J, Xie L, Honig BH, & Rudnick G (2008). Mechanism for Alternating Access in Neurotransmitter Transporters. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105, 10338–10343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804659105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin JS, Larson GA, Swant J, Sen N, Javitch JA, Zahniser NR, … Khoshbouei H (2009). Amphetamine and Methamphetamine Differentially Affect Dopamine Transportersin Vitroandin Vivo. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 284, 2978–2989. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805298200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BJ, Rodrigues APC, ElSawy KM, McCammon JA, & Caves LSD (2006). Bio3d: An R Package for the Comparative Analysis of Protein Structures. Bioinformatics, 22, 2695–2696. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gromek KA, Suchy FP, Meddaugh HR, Wrobel RL, LaPointe LM, Chu UB, … Fox BG (2014). The Oligomeric States of the Purified Sigma-1 Receptor Are Stabilized by Ligands. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 289, 20333–20344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.537993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong WC, Yano H, Hiranita T, Chin FT, McCurdy CR, Su T-P, … Katz JL (2017). The Sigma-1 Receptor Modulates Dopamine Transporter Conformation and Cocaine Binding and May Thereby Potentiate Cocaine Self-Administration in Rats. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 292, 11250–11261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.774075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover WG (1985). Canonical Dynamics: Equilibrium Phase-Space Distributions. Physical Review A, 31, 1695–1697. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevA.31.1695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Rauscher S, Nawrocki G, Ran T, Feig M, de Groot BL, … MacKerell AD (2016). Charmm36m: An Improved Force Field for Folded and Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. Nature Methods, 14, 71–73. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo S, Kim T, Iyer VG, & Im W (2008). Charmm-Gui: A Web-Based Graphical User Interface for Charmm. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 29, 1859–1865. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph D, Pidathala S, Mallela AK, & Penmatsa A (2019). Structure and Gating Dynamics of Na+/Cl– Coupled Neurotransmitter Transporters. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 6, 80. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2019.00080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal N, & Matsumoto R, R. (2011). Role of Sigma Receptors in Methamphetamine-Induced Neurotoxicity. Current Neuropharmacology, 9, 54–57. doi: 10.2174/157015911795016930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal N, Seminerio MJ, Robson MJ, McCurdy CR, & Matsumoto RR (2013). Pharmacological Evaluation of Sn79, a Sigma (Σ) Receptor Ligand, against Methamphetamine-Induced Neurotoxicity in Vivo. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 23, 960–971. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal N, Seminerio MJ, Shaikh J, Medina MA, Mesangeau C, Wilson LL, … Matsumoto RR (2011). Cm156, a High Affinity Sigma Ligand, Attenuates the Stimulant and Neurotoxic Effects of Methamphetamine in Mice. Neuropharmacology, 61, 992–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.06.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klauda JB, Venable RM, Freites JA, O’Connor JW, Tobias DJ, Mondragon-Ramirez C, … Pastor RW (2010). Update of the Charmm All-Atom Additive Force Field for Lipids: Validation on Six Lipid Types. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 114, 7830–7843. doi: 10.1021/jp101759q [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollman P (1993). Free Energy Calculations: Applications to Chemical and Biochemical Phenomena. Chemical Reviews, 93, 2395–2417. doi: 10.1021/cr00023a004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kollman PA, Massova I, Reyes C, Kuhn B, Huo S, Chong L, … Cheatham TE (2000). Calculating Structures and Free Energies of Complex Molecules: Combining Molecular Mechanics and Continuum Models. Accounts of Chemical Research, 33, 889–897. doi: 10.1021/ar000033j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy H, & Gouaux E (2012). X-Ray Structures of Leut in Substrate-Free Outward-Open and Apo Inward-Open States. Nature, 481, 469–474. doi: 10.1038/nature10737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari R, Kumar R, & Lynn A (2014). g_mmpbsa—a Gromacs Tool for High-Throughput Mm-Pbsa Calculations. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 54, 1951–1962. doi: 10.1021/ci500020m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutzner C, Páll S, Fechner M, Esztermann A, Groot BL, & Grubmüller H (2019). More Bang for Your Buck: Improved Use of Gpu Nodes for Gromacs 2018. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 40, 2418–2431. doi: 10.1002/jcc.26011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Cheng X, Swails JM, Yeom MS, Eastman PK, Lemkul JA, … Im W (2015). Charmm-Gui Input Generator for Namd, Gromacs, Amber, Openmm, and Charmm/Openmm Simulations Using the Charmm36 Additive Force Field. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 12, 405–413. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MS, Salsbury FR, & Brooks CL (2002). Novel Generalized Born Methods. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 116, 10606–10614. doi: 10.1063/1.1480013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leviel V (2011). Dopamine Release Mediated by the Dopamine Transporter, Facts and Consequences. Journal of Neurochemistry, 118, 475–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07335.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z, & Uhl GR (2002). Dopamine Transporter Mutants with Cocaine Resistance and Normal Dopamine Uptake Provide Targets for Cocaine Antagonism. Molecular Pharmacology, 61, 885–891. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.4.885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomize MA, Pogozheva ID, Joo H, Mosberg HI, & Lomize AL (2012). Opm Database and Ppm Web Server: Resources for Positioning of Proteins in Membranes. Nucleic Acids Research, 40(D1), D370–D376. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto RR, Nguyen L, Kaushal N, & Robson MJ (2014). Sigma (σ) Receptors as Potential Therapeutic Targets to Mitigate Psychostimulant Effects. Advances in Pharmacology, 69, 323–386. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-420118-7.00009-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto RR, Shaikh J, Wilson LL, Vedam S, & Coop A (2008). Attenuation of Methamphetamine-Induced Effects through the Antagonism of Sigma (σ) Receptors: Evidence from in Vivo and in Vitro Studies. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 18, 871–881. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra AK, Mavlyutov T, Singh DR, Biener G, Yang J, Oliver Julie A., … Raicu V (2015). The Sigma-1 Receptors Are Present in Monomeric and Oligomeric Forms in Living Cells in the Presence and Absence of Ligands. Biochemical Journal, 466, 263–271. doi: 10.1042/bj20141321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS, & Olson AJ (2009). Autodock4 and Autodocktools4: Automated Docking with Selective Receptor Flexibility. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 30, 2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen EC, McCracken KA, Liu Y, Pouw B, & Matsumoto RR (2005). Involvement of Sigma (Σ) Receptors in the Acute Actions of Methamphetamine: Receptor Binding and Behavioral Studies. Neuropharmacology, 49, 638–645. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L, Kaushal N, Robson MJ, & Matsumoto RR (2014). Sigma Receptors as Potential Therapeutic Targets for Neuroprotection. European Journal of Pharmacology, 743, 42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.09.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L, Lucke-Wold BP, Mookerjee SA, Cavendish JZ, Robson MJ, Scandinaro AL, & Matsumoto RR (2015). Role of Sigma-1 Receptors in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences, 127, 17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2014.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen AK, Möller IR, Wang Y, Rasmussen SGF, Lindorff-Larsen K, Rand KD, & Loland CJ (2019). Substrate-Induced Conformational Dynamics of the Dopamine Transporter. Nature Communications, 10, 2714. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10449-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosé S (1984). A Unified Formulation of the Constant Temperature Molecular Dynamics Methods. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 81, 511–519. doi: 10.1063/1.447334 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parrinello M, & Rahman A (1980). Crystal Structure and Pair Potentials: A Molecular-Dynamics Study. Physical Review Letters, 45, 1196–1199. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.45.1196 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parrinello M, & Rahman A (1981). Polymorphic Transitions in Single Crystals: A New Molecular Dynamics Method. Journal of Applied Physics, 52, 7182–7190. doi: 10.1063/1.328693 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y, Dong H, & Welsh WJ (2018). Comprehensive 3d-Qsar Model Predicts Binding Affinity of Structurally Diverse Sigma 1 Receptor Ligands. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 59, 486–497. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.8b00521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossino G, Orellana I, Caballero J, Schepmann D, Wünsch B, Rui M, … Vergara-Jaque A (2019). New Insights into the Opening of the Occluded Ligand-Binding Pocket of Sigma1 Receptor: Binding of a Novel Bivalent Rc-33 Derivative. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 60, 756–765. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambo DO, Lebowitz JJ, & Khoshbouei H (2018). The Sigma-1 Receptor as a Regulator of Dopamine Neurotransmission: A Potential Therapeutic Target for Methamphetamine Addiction. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 186, 152–167. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambo DO, Lin M, Owens A, Lebowitz JJ, Richardson B, Jagnarine DA, … Khoshbouei H (2017). The Sigma-1 Receptor Modulates Methamphetamine Dysregulation of Dopamine Neurotransmission. Nature Communications, 8. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02087-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt HR, Betz RM, Dror RO, & Kruse AC (2018). Structural Basis for σ1 Receptor Ligand Recognition. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 25, 981–987. doi: 10.1038/s41594-018-0137-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt HR, Zheng S, Gurpinar E, Koehl A, Manglik A, & Kruse AC (2016). Crystal Structure of the Human Σ1 Receptor. Nature, 532, 527–530. doi: 10.1038/nature17391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey J, Glen KA, Wolfe S, & Kuhar MJ (1988). Cocaine Binding at σ Receptors. European Journal of Pharmacology, 149, 171–174. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90058-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitte HH (2004). Sodium-Dependent Neurotransmitter Transporters: Oligomerization as a Determinant of Transporter Function and Trafficking. Molecular Interventions, 4, 38–47. doi: 10.1124/mi.4.1.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skjærven L, Yao X-Q, Scarabelli G, & Grant BJ (2014). Integrating Protein Structural Dynamics and Evolutionary Analysis with Bio3d. BMC Bioinformatics, 15, 399. doi: 10.1186/s12859-014-0399-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia MA, Lever JR, Lever SZ, Will MJ, Park ES, & Miller DK (2019). Sigma-1 Receptor Ligand Pd144418 and Sigma-2 Receptor Ligand Yun-252 Attenuate the Stimulant Effects of Methamphetamine in Mice. Psychopharmacology, 236, 3147–3158. doi: 10.1007/s00213-019-05268-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tovchigrechko A, & Vakser IA (2005). Development and Testing of an Automated Approach to Protein Docking. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics, 60, 296–301. doi: 10.1002/prot.20573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tovchigrechko A, & Vakser IA (2006). Gramm-X Public Web Server for Protein-Protein Docking. Nucleic Acids Research, 34(Web Server), W310–W314. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vangone A, & Bonvin AMJJ (2015). Contacts-Based Prediction of Binding Affinity in Protein–Protein Complexes. eLife, 4, e07454. doi: 10.7554/eLife.07454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanommeslaeghe K, Hatcher E, Acharya C, Kundu S, Zhong S, Shim J, … Mackerell AD (2009). Charmm General Force Field: A Force Field for Drug-Like Molecules Compatible with the Charmm All-Atom Additive Biological Force Fields. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 31, 671–690. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan RA, & Foster JD (2013). Mechanisms of Dopamine Transporter Regulation in Normal and Disease States. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 34, 489–496. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Chang L, Wang G-J, Fowler JS, Franceschi D, Sedler M, … Logan J (2001). Loss of Dopamine Transporters in Methamphetamine Abusers Recovers with Protracted Abstinence. The Journal of Neuroscience, 21, 9414–9418. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.21-23-09414.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Cieplak P, & Kollman PA (2000). How Well Does a Restrained Electrostatic Potential (Resp) Model Perform in Calculating Conformational Energies of Organic and Biological Molecules? Journal of Computational Chemistry, 21, 1049–1074. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang KH, Penmatsa A, & Gouaux E (2015). Neurotransmitter and Psychostimulant Recognition by the Dopamine Transporter. Nature, 521, 322–327. doi: 10.1038/nature14431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Fu T, Zhang X, Yang F, Zheng G, Xue W, … Zhu F (2017). Differentiating Physicochemical Properties between Ndris and Snris Clinically Important for the Treatment of Adhd. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects, 1861, 2766–2777. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2017.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Zhang X, Fu T, Li S, Li B, Xue W, … Zhu F (2017). Differentiating Physicochemical Properties between Addictive and Nonaddictive Adhd Drugs Revealed by Molecular Dynamics Simulation Studies. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 8, 1416–1428. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb B, & Sali A (2016). Comparative Protein Structure Modeling Using Modeller. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics, 54, 5.6.1–5.6.37. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, & Chen LY (2020). Identification of a New Allosteric Binding Site for Cocaine in Dopamine Transporter. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 60, 3958–3968. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue W, Fu T, Zheng G, Tu G, Zhang Y, Yang F, … Zhu F (2020). Recent Advances and Challenges of the Drugs Acting on Monoamine Transporters. Current Medicinal Chemistry, 27, 3830–3876. doi: 10.2174/0929867325666181009123218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue W, Wang P, Tu G, Yang F, Zheng G, Li X, … Zhu F (2018). Computational Identification of the Binding Mechanism of a Triple Reuptake Inhibitor Amitifadine for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 20, 6606–6616. doi: 10.1039/c7cp07869b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano H, Bonifazi A, Xu M, Guthrie DA, Schneck SN, Abramyan AM, … Shi L (2018). Pharmacological Profiling of Sigma 1 Receptor Ligands by Novel Receptor Homomer Assays. Neuropharmacology, 133, 264–275. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.01.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen J, Antonio T, Cheng S-Y, Ali S, Jones KT, & Reith MEA (2015). Dopamine Transporter Oligomerization: Impact of Combining Protomers with Differential Cocaine Analog Binding Affinities. Journal of Neurochemistry, 133, 167–173. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.