Abstract

Background:

The cost of cancer care is rising and represents a stressor that has significant and lasting effects on quality of life for many patients and caregivers. Adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer are particularly vulnerable. Financial burden measures exist but have varying evidence for their validity and reliability. The goal of this systematic review is to summarize and evaluate measures of financial burden in cancer and describe their potential utility among AYAs and their caregivers.

Methods:

We searched PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, CINAHL and PsychINFO for concepts involving financial burden, cancer, and self-reported questionnaires, limiting the results to the English language. We discarded meeting abstracts, editorials, letters, and case reports. We used standard screening and evaluation procedures for selecting and coding studies, including consensus-based standards for documenting measurement properties and study quality.

Results:

We screened 7,250 abstracts and 720 full-text articles to identify relevant articles on financial burden. Of those, 86 met our inclusion criteria. Data extraction revealed 64 unique measures that assess financial burden across material, psychosocial, and behavioral domains. One measure was developed specifically for AYAs and none for their caregivers. The psychometric evidence and study qualities revealed mixed evidence of methodological rigor.

Conclusion:

Several measures assess the financial burden of cancer. They were primarily designed and evaluated in adult patient populations with little focus on AYAs or caregivers, despite their increased risk of financial burden. These findings highlight opportunities to adapt and test existing measures of financial burden for AYAs and their caregivers.

Keywords: cancer, measurement, finances, systematic review, young adult, caregivers

Precis:

Many self-report measures of financial burden in cancer exist, but very few have adequate data to support robust psychometric properties or capture material, psychosocial, and behavioral domains. A particularly salient need is to adapt and test existing measures of financial burden for AYAs and their caregivers.

Background

The cost of cancer care is rising and represents a significant stressor with lasting effects on quality of life for patients and their caregivers.1–3 Survivors of cancer are more likely to report higher out-of-pocket medical costs, work-related productivity loss, depletion of assets, and medical debt including bankruptcy than those without a cancer history.4–6 Moreover, the adverse financial impact of cancer is often shared by family caregivers (e.g., parents, partners, siblings), with 25% of caregivers reporting high levels of financial strain from decreasing financial assets, increasing out-of-pocket costs, and productivity loss in their jobs.7–9

Adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer, defined as those diagnosed with cancer from the ages of 15 to 39 years old,10 are particularly vulnerable to the financial burden of cancer care. Worldwide, there are more than 1,000,000 new diagnoses of cancer annually in AYAs.11 Inadequate insurance coverage and limited financial assets place AYAs at greater risk of financial burden compared to any other age group with cancer.12–14 The AYA population is increasingly racially and ethnically diverse. Although not well-characterized in AYA research, racial and/or ethnic disparities in financial burden are well-documented in cancer research,15, 16 suggesting that racial/ethnic AYA minority groups may have additional risk for financial burden compared to white AYA cancer survivors.

Multiple terms have been used to describe the adverse financial impact of cancer such as financial hardship, financial burden, financial toxicity, and financial distress.5, 13, 17–29 We define financial burden as the adverse impact of cancer and treatment-related costs on patients and/or their families. Consistent with current multidimensional perspectives offered in cancer survivorship research, financial burden may include material (e.g., reduction in income, medical debt), psychosocial (i.e., distress about medical costs), and behavioral domains (i.e., strategies such as forgoing medical care).30–32

Multiple measures have been developed to assess financial burden with the vast majority focusing on the material dimension and relatively less attention paid to psychosocial or behavioral dimensions.30 To advance screening and treatment of this critical problem, a synthesis and evaluation of existing measures of financial burden is needed. Therefore, our goal is to build upon existing systematic reviews30, 33 and to extend those reviews in important new directions by summarizing and evaluating the psychometric properties of financial burden measures in cancer for all patients and caregivers while describing their potential utility among AYAs and their caregivers specifically. We sought to address three key questions: (1) How is self-reported financial burden assessed from the cancer patient or caregiver perspective?; (2) What are the psychometric properties of the available financial burden measures?; and (3) Which measures show potential utility for AYAs with cancer and caregivers in particular?

Methods

Search Strategy

A reference librarian designed the literature search to identify published studies. We searched PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, CINAHL Complete (Ebsco) and PsycINFO (Ebsco), through March 20, 2019, using a combination of relevant subject headings, concepts, and text words involving financial burden, cancer, and self-reported questionnaires. Detailed strategies are available in Supplemental Table 1.

Eligibility Criteria

Eligibility criteria included (a) peer-reviewed journal articles; (b) empirical studies; (c) English language publications and measure; (d) defined cancer sample or subsample (any age, type, or phase of treatment) or their caregivers/proxies; (e) inclusion of self- or proxy-report measure(s) of the personal or family subjective financial impact for patients or their caregivers/proxies; (f) report scores for subscales/subdomains individually or in aggregate form; and (g) report psychometric evidence for the measure (i.e., some evidence of reliability or validity). Case studies, commentaries, conference abstracts, reviews, dissertations, or qualitative research unrelated to measurement development were excluded. We also excluded studies that solely focused on out-of-pocket costs. While these costs are important objective indicators of financial burden, they capture only one aspect of the material dimension and do not fully reflect the broader financial burden experienced by patients and their caregivers.

Study Selection

Covidence (v1906), a Cochrane technology platform, was used to manage study reviews and coding. Abstracts were initially screened in sets of 20 by all reviewers to determine whether they met inclusion criteria for full text review. Conflicts were discussed as a group, and we screened another set of 20 abstracts until there was good agreement among reviewers (≥80%). Subsequently, individual rater pairs screened the remaining abstracts. Full-text articles were retrieved for all potentially eligible abstracts and independently screened by rater pairs. The lead author, in consultation with the larger study team, resolved any discrepancies to determine the final set of studies included in the review.

Data Coding

Rater pairs then independently extracted data elements from all eligible full-text articles. Any discrepancies in extracted data were resolved through discussion among raters until consensus was reached. Demographic (sample size, age, % women, % racial or ethnic minorities), clinical (cancer type, stage, phase of cancer care), study characteristics (country, research design), and measure characteristics were extracted. Measure characteristics including instrument name, type (patient- or caregiver-reported), financial burden domain assessed (e.g., material, psychosocial, or behavioral), number of questions, number and type of responses, and recall period. In addition, two PhD trained psychometricians extracted data on the evidence for the reliability and validity of all measures.

Psychometric Properties & Study Quality Assessment

A subset of the identified measures of financial burden were selected for a more detailed review. The selected measures had to be multi-item scales from psychometric studies with some evidence for both their reliability and validity in patients with cancer. The psychometricians independently evaluated each instrument based on modified COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) criteria34 (Supplemental Table 2). Key COSMIN modifications included the additions of category of score interpretability and of rating level of “very good” above “adequate/sufficient”. Criteria included evidence for the instrument’s structural validity, internal consistency reliability, test-retest reliability, content validity, criterion validity, construct validity, cross-cultural validity/measurement invariance, responsiveness, and interpretability of scores. When multiple studies included the same measure, criteria ratings were based on the cumulative evidence across all relevant studies. Each criterion was graded as very good, adequate, inadequate, or not reported. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Lastly, the psychometricians reviewed each of these studies individually to evaluate the overall quality of the study, using a modified version of the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies.35 Criteria were selected based on their relevance to studies of psychometric properties and so we excluded items that only applied to cohort studies with an epidemiological focus (e.g., assessment of exposure over time). We included the study’s clarity of objective, defined population, appropriateness of participation rate, justified sample size for study objective, appropriate assessment points, well defined variables, and limited loss to follow-up. Criteria were rated as yes, no, or not reported.

Results

Study Selection

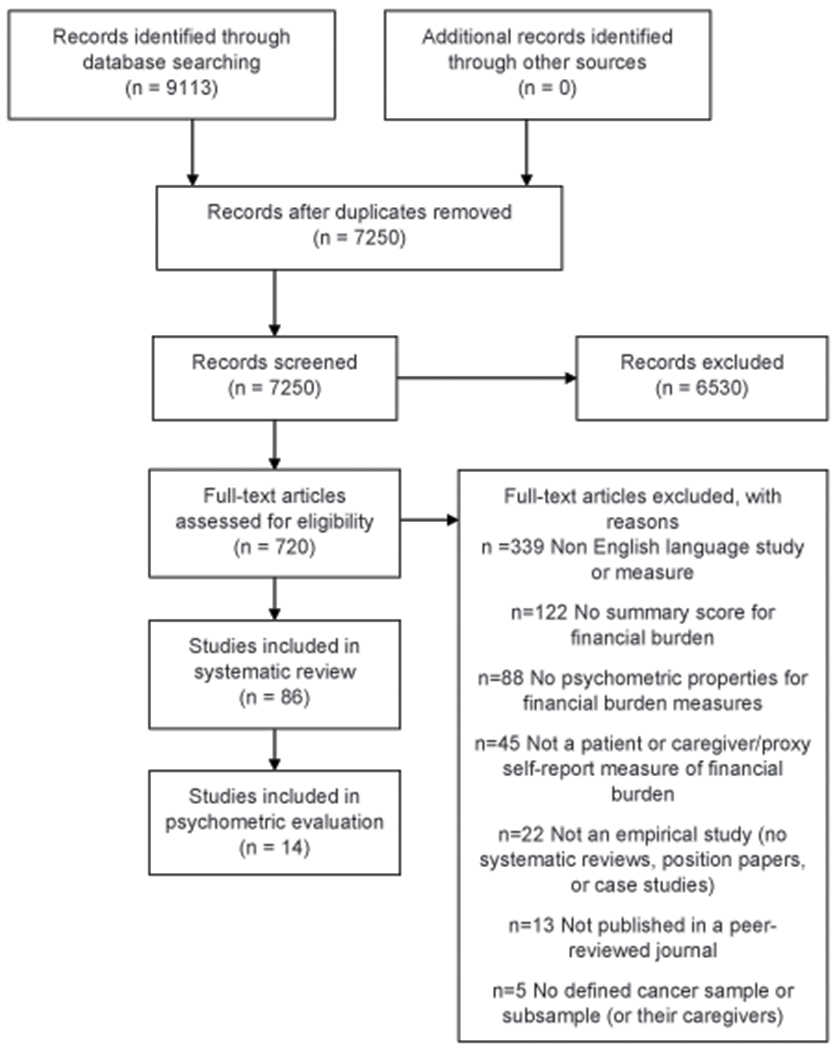

The search of the electronic databases retrieved 9,113 citations (Figure 1). After removal of duplicates, 7,250 remained and were evaluated based on title and abstract. Of these, 6,530 did not meet the inclusion criteria. 720 potentially relevant references were screened with a full text review. Of these, 86 studies met inclusion criteria and yielded summary data for reliability and/or validity of financial burden measures. Fourteen studies (comprising 10 measures) had sufficient information for further, in-depth psychometric evaluation.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Overall Description of Studies and Measure Characteristics

Eighty-six studies were included in our review, accounting for over 55,000 patients and nearly 4,000 caregivers (e.g., parent, spouse/partner, or other family member). Seventy-nine percent (68/86) were published in the last decade with 74% (50/68) of those within the last five years. The majority of studies focused on U.S. samples (80%; 69/86) and included mixed cancer types (73%; 63/86). The samples were primarily female (72% of studies included >50% female participants; 62/86). Only 15% of studies had ≥30% racial/ethnic minority representation (13/86), and only 9% of studies included a majority of AYAs in their sample (8/86; with four of those eight studies focusing on adult survivors of pediatric cancers). The vast majority of studies used a quantitative approach (97%; 83/86). Cross-sectional designs (73%; 63/86) were more than three times as common as longitudinal ones (23%; 20/86). Only a few studies used either a mixed-methods approach (2%; 2/86)36, 37 or a qualitative approach (1%; 1/86).38 Supplemental Table 3 provides study characteristics by individual project.

Overall, we identified 64 unique measures used to assess financial burden in cancer survivorship. Of these, 49 were multi-item measures and 15 were single item measures of financial burden. All measures reviewed were designed for adult self-report with 81% (52/64) patient-reported measures of financial burden and 23% (15/64) caregiver-reported measures (three measures had both caregiver and patient versions and none were proxy-reported measures). One measure was developed specifically for AYAs but focused on survivors of childhood cancer39, and no measures were designed for caregivers of AYAs. The material domain of financial burden was captured by 70% of measures (45/64), followed closely by the psychosocial (61%; 39/64) and behavioral (44%; 28/56) domains. Only twelve measures captured content from all three domains (19%; 12/64). Supplemental Table 4 provides additional details about specific financial burden items/measures for individual studies.

Psychometric Analysis and Study Quality

Ten measures (8 patient-reported; 2 caregiver-reported) from 14 studies were identified for in-depth evaluation of their psychometric properties. Across the 9 COSMIN criteria used to evaluate the psychometric qualities of the individual measures, combined ratings of “adequate” or “very good” ranged from 44% to 78% (Table 1). The Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity (COST),25, 26 Patient Roles and Responsibilities Scale,40 and Singapore Caregiver Quality of Life Scale: Financial Well-being Subscale41 all received ratings of “adequate” or “very good” across >60% of the categories. None of the patient-reported measures provided sufficient information to merit “adequate” or “very good” ratings for criterion validity, cross-cultural validity/measurement invariance, or responsiveness. Only the caregiver-reported measure, the Singapore Caregiver Quality of Life Scale: Financial Well-being Subscale, had sufficient data to receive an “adequate”/”very good” rating for cross-cultural validity/measurement invariance. Notably, the Impact of Cancer for Childhood Cancer Survivors: financial problems subscale39 was the only measure specific to AYAs, receiving ratings of “adequate” or “very good” across a majority (56%) of the COSMIN criteria. Only two measures, the Patient Roles and Responsibilities Scale40 and the Caregiver Roles and Responsibilities Scale42 included item content across all three domains of financial burden: material, psychosocial, and behavioral. The study quality was uniformly strong for each of these 14 studies (Table 2).

Table 1.

Psychometric Properties of Financial Burden Measures

| Measure Name | Structural Validity | Internal Consistency | Reliability | Construct Validity | Cross-Cultural Validity/Measurement Invariance | Criterion Validity | Responsiveness | Interpretability | Content Validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-Reported | |||||||||

| Cancer Problem-in-Living Scale38, 63 | very good | adequate | not reported | adequate | not reported | not reported | not reported | adequate | adequate |

| Chronic Cancer Experiences Questionnaire37 | adequate | adequate | not reported | adequate | not reported | not reported | not reported | adequate | very good |

| Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity25, 26 | very good | very good | adequate | very good | inadequate | not reported | not reported | adequate | very good |

| Impact of Cancer for Childhood Cancer Survivors: Financial Problems subscale39 | very good | adequate | inadequate | very good | not reported | not reported | not reported | very good | very good |

| Patient Roles and Responsibilities Scale: Financial Well-being subscale40 | very good | adequate | adequate | adequate | not reported | not reported | inadequate | adequate | very good |

| Quality of Life in Adult Cancer Survivors: Financial Problems subscale36, 54, 64 | very good | adequate | not reported | very good | not reported | not reported | not reported | adequate | very good |

| Socioeconomic Well-Being Scale: Material Capital subscale65 | very good | very good | not reported | very good | not reported | not reported | not reported | adequate | very good |

| Not reported (study-specific measure of financial burden/worry)66 | very good | adequate | not reported | adequate | not reported | not reported | not reported | very good | not reported |

| Caregiver-Reported | |||||||||

| Singapore Caregiver Quality of Life Scale: Financial Well-being subscale41 | very good | very good | adequate | very good | very good | not reported | not reported | adequate | very good |

| Caregiver Roles & Responsibilities Scale: Financial Well-being subscale42 | very good | adequate | adequate | not reported | not reported | not reported | not reported | adequate | very good |

Table 2.

Study Quality Assessment

| Measure Name | Study | Objective | Study Population | Participation Rate | Sample Size Justification | Sufficient Timeframe | Variables Defined | Loss to Follow-Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-Reported | ||||||||

| Cancer Problem-in-Living Scale: Employment/Financial Problems subscale | Baker 199938 | Yes | Yes | NR | NA | Yes | NA | Yes |

| Zhao 200963 | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | NA | Yes | NA | |

| Chronic Cancer Experiences Questionnaire: Financial Advice subscale | Harley 201937 | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | NA | Yes | NA |

| Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity | de Souza 201426 | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA |

| de Souza 2017b25 | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | |

| Impact of Cancer for Childhood Cancer Survivors: Financial Problems subscale | Zebrack 201039 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Patient Roles and Responsibilities Scale: Financial Well-being subscale | Shilling 201840 | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | NR | Yes | Yes |

| Quality of Life in Adult Cancer Survivors: Financial Problems subscale | Avis 200536 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Carver 200664 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | |

| Morrow 201454 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | NA | |

| Socioeconomic Well-Being Scale: Material Capital subscale | Head 200865 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Not reported (study-specific measure of financial burden/worry) | Veenstra 201466 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Caregiver-Reported | ||||||||

| Singapore Caregiver Quality of Life Scale: Financial Well-being Subscale | Cheung 201941 | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Caregiver Roles & Responsibilities Scale: Financial Well-being subscale | Shilling 201942 | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Note: NA= not applicable, NR=not reported

Discussion

Interest in the patient and caregiver experience of financial hardship has burgeoned in the last decade as evidenced by a doubling of the number of publications during that time. Capturing and accurately representing patient and caregiver experiences of financial burden is critical to advance research and clinical practice and to develop interventions that address the financial burden of cancer survivors and their caregivers. The current systematic review addresses an important gap in the literature by including an assessment of measures specifically for use among AYAs. Overall, we found that although many self-report measures of financial burden exist, very few have adequate data to support robust psychometrics, most do not assess all three domains of financial burden, and almost none focus on AYAs or their caregivers. Measure characteristics, including their psychometric strengths and limitations, their evidence for use among AYAs, and implications for research are discussed below.

Patient reports of financial burden accounted for 52 unique measures in our systematic review; caregiver-reports accounted for 15. Collectively, these self-report approaches included multi-item scales that yield overall financial burden scores,25, 43 multi-item scales that yield financial burden subscale scores,39, 44, 45 and single-item approaches developed de novo for individual research studies5, 46–48 or drawn from existing, population-based research studies.19, 20, 22, 49 While brief assessments are desired for reduced respondent burden, they may not capture the breadth and depth of the financial burden experience of cancer survivors and caregivers.

Conceptual models of financial burden in cancer emphasize the material, psychosocial, and behavioral domains.31 Whereas the material domain can be partially indicated by objective cost data (e.g., out-of-pocket expenditures), self-report data remain critical to describe other aspects of the material burden (e.g., reduction in household income) experienced by cancer survivors and their caregivers. Self-report data are especially relevant for the psychosocial and behavioral domains that capture how cancer survivors and their caregivers feel about financial burden (e.g., distress from the reduction in financial resources) and the purposeful effort they engage in to “make ends meet” (e.g., financial adjustments to balance household budgets) as they manage and navigate cancer survivorship. Of the measures included in our review, 19% had item content that reflected all three domains. As expected, the material dimension was the most frequently assessed domain of financial burden in this review, captured by 70% of measures. However, the psychosocial and behavioral domains were relatively well-represented, captured by 61% and 44%, respectively. The encouraging representation of psychosocial and behavioral domains may reflect the use of newer measures of financial burden (e.g., COST) and appreciation for a need to progress from an over-reliance on material aspects of financial burden to inform a more complete understanding of patient and caregiver experiences.

Only ten measures (eight patient-report and two caregiver-report) provided adequate psychometric detail to inform a rigorous evaluation of their quality among patients and caregivers with cancer. Further, only two of those measures captured all three domains of financial burden. Of the ten measures we evaluated, the majority demonstrated “adequate” to “very good” ratings across multiple psychometric criteria. In general, these measures demonstrated relative strengths in their structural validity, internal consistency reliability, test-retest reliability, construct validity, interpretability, and content validity. However, additional testing and evaluation is needed to demonstrate greater utility of these measures. First, responsiveness, criterion validity, and cross-cultural validity/measurement invariance were largely absent. The Financial Well-being subscale of the Singapore Caregiver Quality of Life Scale41 was the only measure that provided sufficiently strong support for this psychometric category. Very few of the measures were tested among sizeable subgroups of racial or ethnic minority participants, rural patients, or even AYAs who may be more likely to be uninsured or underinsured and thus at greater risk of financial burden.12–14, 50–55 Second, too few studies leveraged longitudinal designs to inform assessments of responsiveness and criterion validity. Since financial burden may fluctuate over time and across the cancer care continuum,56 longitudinal designs are needed to address the lack of responsiveness data. Longitudinal approaches can also strengthen the evidence base for criterion validity.

Lastly, only one scale was designed to assess the financial burden among AYAs. The Financial Problems subscale of the Impact of Cancer Scale is a brief assessment of the adverse impact of financial burden among post-treatment survivors.39 However, it was validated with adult survivors of childhood cancer. Other promising measures, the COST and the Patient Roles and Responsibilities Scale have had limited testing with AYA subgroups.25, 40 The lack of validated measures of financial burden among AYAs represents an important opportunity to adapt and test existing measures or to develop new measures to address this critical gap. This is important, as changing healthcare coverage among AYAs in their mid-20s as they age out of eligibility for extended coverage under their parents’ insurance through the Affordable Care Act presents additional challenges.29 Similarly, older AYAs may be at particular risk as many have mortgages and dependents with fewer financial reserves.57 Altogether, these unique factors underscore the importance of capturing the lived experiences, developmental milestones, and perspectives of AYA patients and their caregivers managing the financial burden of cancer.

No caregiver studies were specifically focused on AYAs, though a small number of studies focused on caregivers of pediatric patients with cancer.24, 55, 58–60 These were rarely older adolescents (ages 15-17) or emerging adults (ages 18-25). Assessing the financial experience of these AYA and caregiver subgroups is critical, as they face unique financial needs and challenges. The subjective experience of financial burden among older adolescents may not warrant assessment as their caregivers often maintain primary financial responsibility. In contrast, emerging adults are navigating financial autonomy and independence from their parent caregiver(s), perhaps heightening distress about the financial impact of cancer. As emerging adults may be living at home or pursuing educational goals and not financially established, their parent caregivers may assume additional and more persistent financial responsibility, compromising their own financial well-being. For emerging adults whose caregivers are a partner, significant other, or sibling, financial burden may be experienced differently by both the cancer patient and the caregiver. Assessing the caregiver perspective alone is likely sufficient for older adolescents but assessing the patient and caregiver perspective in tandem would be ideal for evaluating financial burden among emerging adults. These nuances need to be considered in research designs as well as measurement development for AYAs and their caregivers.

This study has limitations. We restricted our search to English language measures and measures tested among patients with cancer or their caregivers. Although measures developed and tested in non-English languages or among other health conditions may further inform assessment of financial burden, the cost of cancer care in the United States is rapidly rising and embedded within existing federal health policy environments.61 A majority of participants were adult women who were not AYAs and there was little racial or ethnic minority representation. Thus, the particular experiences of financial burden, including behavioral strategies for managing the costs of cancer, may not generalize to groups that are more diverse. Another limitation is we did not include measures that assessed out-of-pocket costs for patients and families. While this is a critically important aspect of financial burden in cancer, out-of-pocket costs only inform one aspect of the material subdomain. We prioritized the self-reported subjective perspective and ensured sufficient breadth by exploring material as well as psychosocial and behavioral domains of financial burden in cancer.31

Despite these limitations, this study had a number of strengths that increase the impact of this work. This is the first systematic review and psychometric evaluation of measures of financial burden for patients with cancer and their caregivers. Our review was pre-registered in PROSPERO and adhered to the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” guidelines.62 Our comprehensive search of five databases included multiple reviewer pairs, counter-balanced to minimize rater bias. All reviewers had advanced doctoral degrees and represented a diversity of training backgrounds (measurement science, clinical psychology, pediatric psychology, social welfare, health education, and public health). Data extracted from all studies focused on demographic, clinical, and measure characteristics, including reliability and validity. For measures that provided more detailed psychometric data, we conducted in-depth evaluations of the psychometric rigor and study quality using consensus standards. We identified a number of strengths and specific recommendations for next steps.

Summary and future directions

In closing, this timely project highlights the need for more research on the measurement of financial burden among AYA cancer survivors and their caregivers. We have provided a thorough and detailed description of the available measures used to assess financial burden for cancer survivors and caregivers. Some of these measures have sufficiently strong psychometric properties to merit further use and evaluation. Unfortunately, relatively little attention has been focused on financial burden among at-risk patient populations, including AYAs and their caregivers. This gap in the literature represents a crucial opportunity to adapt and test existing measures of financial burden for AYAs and their caregivers. Serial assessment could be used to better understand the impact of financial burden over time, identify who might be most at risk, and determine when they are most in need of support. Accurate assessment is a key step in ensuring that patients and families have a voice in their experience and can inform and contribute to the development, implementation, and evaluation of supportive care interventions to inform patient advocacy, better address their needs, influence health policy, and ultimately reduce the adverse impact of financial burden.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We thank our two reference librarians from Wake Forest Baptist Health, Janine Tillett, MSLS, AHIP, and Rochelle P. Kramer, MLS, for their contributions in designing search strategies. We apologize for driving them into retirement.

Funding:

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01CA218398 (PI: Salsman). Dr. McLouth was supported by R25CA122061 (PI: Avis). Dr. Nightingale was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH (UL1TR001420). This review was registered in PROSPERO 2018 CRD42018115267 and is available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018115267.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

References

- 1.Lee JA, Roehrig CS, Butto ED. Cancer care cost trends in the United States: 1998 to 2012. Cancer. 2016;122: 1078–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon N, Stemmer SM, Greenberg D, Goldstein DA. Trajectories of injectable cancer drug costs after launch in the United States. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36: 319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR. Minimizing the "financial toxicity" associated with cancer care: advancing the research agenda. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2016;108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guy GP Jr., Ekwueme DU, Yabroff KR, et al. Economic burden of cancer survivorship among adults in the United States. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31: 3749–3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patien’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18: 381–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banegas MP, Guy GP Jr., de Moor JS, et al. For Working-Age Cancer Survivors, Medical Debt And Bankruptcy Create Financial Hardships. Health Affairs. 2016;35: 54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Moor JS, Dowling EC, Ekwueme DU, et al. Employment implications of informal cancer caregiving. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2017;11: 48–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, et al. Caring for caregivers and patients: research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer. 2016;122: 1987–1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Alliance for Caregiving. Cancer caregiving in the US: an intense, episodic, and challenging care experience: National Alliance for Caregiving; Bethesda, MD, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, LIVESTRONG™ Young Adult Alliance. Closing the gap: research and care imperatives for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Available from URL: http://planning.cancer.gov/library/AYAO_PRG_Report_2006_FINAL.pdf [accessed April 6, 2008]. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bleyer A, Ferrari A, Whelan J, Barr RD. Global assessment of cancer incidence and survival in adolescents and young adults. Pediatric Blood and Cancer. 2017;64: e26497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guy GP Jr., Yabroff KR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Estimating the health and economic burden of cancer among those diagnosed as adolescents and young adults. Health Affairs. 2014;33: 1024–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kale HP, Carroll NV. Self-reported financial burden of cancer care and its effect on physical and mental health-related quality of life among US cancer survivors. Cancer. 2016;122: 283–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith AW, Parsons HM, Kent EE, et al. Unmet Support Service Needs and Health-Related Quality of Life among Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: The AYA HOPE Study. Front Oncol. 2013;3: 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jagsi R, Pottow JA, Griffith KA, et al. Long-term financial burden of breast cancer: experiences of a diverse cohort of survivors identified through population-based registries. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32: 1269–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pisu M, Kenzik KM, Oster RA, et al. Economic hardship of minority and non-minority cancer survivors 1 year after diagnosis: another long-term effect of cancer? Cancer. 2015;121: 1257–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang IC, Bhakta N, Brinkman TM, et al. Determinants and Consequences of Financial Hardship Among Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report From the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2019;111: 189–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tucker-Seeley RD, Abel GA, Uno H, Prigerson H. Financial hardship and the intensity of medical care received near death. Psycho-Oncology. 2015;24: 572–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP Jr., et al. Financial Hardship Associated With Cancer in the United States: Findings From a Population-Based Sample of Adult Cancer Survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34: 259–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng Z, Jemal A, Han X, et al. Medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chino F, Peppercorn J, Taylor DH Jr., et al. Self-reported financial burden and satisfaction with care among patients with cancer. Oncologist. 2014;19: 414–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fenn KM, Evans SB, McCorkle R, et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’ quality of life. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10: 332–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nipp RD, Kirchhoff AC, Fair D, et al. Financial Burden in Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35: 3474–3481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warner EL, Kirchhoff AC, Nam GE, Fluchel M. Original Contribution. Financial Burden of Pediatric Cancer for Patients and Their Families. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11: 12–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Wroblewski K, et al. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: The validation of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST). Cancer. 2017;123: 476–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Hlubocky FJ, et al. The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer: The COST measure. Cancer. 2014;120: 3245–3253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delgado-Guay M, Ferrer J, Rieber AG, et al. Financial Distress and Its Associations With Physical and Emotional Symptoms and Quality of Life Among Advanced Cancer Patients. Oncologist. 2015;20: 1092–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meeker CR, Wong YN, Egleston BL, et al. Distress and Financial Distress in Adults With Cancer: An Age-Based Analysis. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2017;15: 1224–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salsman JM, Bingen K, Barr RD, Freyer DR. Understanding, measuring, and addressing the financial impact of cancer on adolescents and young adults. Pediatric Blood and Cancer. 2019: e27660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR. Financial Hardships Experienced by Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2017;109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tucker-Seeley RD, Thorpe RJ Jr. Material–psychosocial–behavioral aspects of financial hardship: a conceptual model for cancer prevention. The Gerontologist. 2019;59: S88–S93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yabroff KR, Bradley C, Shih Y-CT. Understanding financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States: strategies for prevention and mitigation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2020;38: 292–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanratty B, Holland P, Jacoby A, Whitehead M. Financial stress and strain associated with terminal cancer--a review of the evidence. Palliative Medicine. 2007;21: 595–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prinsen CAC, Mokkink LB, Bouter LM, et al. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Quality of Life Research. 2018;27: 1147–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Heart Lung & Blood Institute. Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. Bethesda: National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Avis NE, Smith KW, McGraw S, Smith RG, Petronis VM, Carver CS. Assessing Quality of Life in Adult Cancer Survivors (QLACS). Quality of Life Research. 2005;14: 1007–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harley C, Pini S, Kenyon L, Daffu-O’Reilly A, Velikova G. Evaluating the experiences and support needs of people living with chronic cancer: development and initial validation of the Chronic Cancer Experiences Questionnaire (CCEQ). BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2019;9: e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baker F, Zabora J, Polland A, Wingard J. Reintegration after bone marrow transplantation. Cancer Practice. 1999;7: 190–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zebrack BJ, Donohue JE, Gurney JG, Chesler MA, Bhatia S, Landier W. Psychometric evaluation of the impact of cancer (IOC-CS) scale for young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Quality of Life Research. 2010;19: 207–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shilling V, Starkings R, Jenkins V, Cella D, Fallowfield L. Development and validation of the patient roles and responsibilities scale in cancer patients. Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 2018;27: 2923–2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheung YB, Neo SHS, Teo I, et al. Development and evaluation of a quality of life measurement scale in English and Chinese for family caregivers of patients with advanced cancers. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2019;17: 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shilling V, Starkings R, Jenkins V, Cella D, Fallowfield L. Development and validation of the caregiver roles and responsibilities scale in cancer caregivers. Quality of Life Research. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prawitz AD, Garman ET, Sorhaindo B, O’Neill B, Kim J, Drentea P. InCharge financial distress/financial well-being scale: Development, administration, and score interpretation. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning. 2006;17. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Avis NE, Ip E, Foley KL. Evaluation of the Quality of Life in Adult Cancer Survivors (QLACS) scale for long-term cancer survivors in a sample of breast cancer survivors. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2006;4: 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Given CW, Given B, Stommel M, Collins C, King S, Franklin S. The caregiver reaction assessment (CRA) for caregivers to persons with chronic physical and mental impairments. Research in Nursing and Health. 1992;15: 271–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Borstelmann NA, Rosenberg SM, Ruddy KJ, et al. Partner support and anxiety in young women with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2015;24: 1679–1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manne S, Kashy D, Albrecht T, et al. Attitudinal barriers to participation in oncology clinical trials: factor analysis and correlates of barriers. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2015;24: 28–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sharp L, Carsin AE, Timmons A. Associations between cancer-related financial stress and strain and psychological well-being among individuals living with cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22: 745–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zheng Z, Han X, Guy GP Jr., et al. Do cancer survivors change their prescription drug use for financial reasons? Findings from a nationally representative sample in the United States. Cancer. 2017;123: 1453–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Palmer NR, Geiger AM, Lu L, Case LD, Weaver KE. Impact of rural residence on forgoing healthcare after cancer because of cost. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention. 2013;22: 1668–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mandaliya H, Ansari Z, Evans T, Oldmeadow C, George M. Psychosocial Analysis of Cancer Survivors in Rural Australia: Focus on Demographics, Quality of Life and Financial Domains. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2016;17: 2459–2464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pagano IS, Gotay CC. Ethnic differential item functioning in the assessment of quality of life in cancer patients. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2005;3: 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Asare M, Peppone LJ, Roscoe JA, et al. Racial Differences in Information Needs During and After Cancer Treatment: a Nationwide, Longitudinal Survey by the University of Rochester Cancer Center National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program. Journal of Cancer Education. 2018;33: 95–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morrow PK, Broxson AC, Munsell MF, et al. Effect of age and race on quality of life in young breast cancer survivors. Clinical Breast Cancer. 2014;14: e21–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramsey LH, Graves PE, Howard Sharp KM, Seals SR, Collier AB, Karlson CW. Impact of Race and Socioeconomic Status on Psychological Outcomes in Childhood Cancer Patients and Caregivers. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chino F, Peppercorn JM, Rushing C, et al. Going for Broke: A Longitudinal Study of Patient-Reported Financial Sacrifice in Cancer Care. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14: e533–e546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Landwehr MS, Watson SE, Macpherson CF, Novak KA, Johnson RH. The cost of cancer: a retrospective analysis of the financial impact of cancer on young adults. Cancer Med. 2016;5: 863–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bona K, Dussel V, Orellana L, et al. Economic impact of advanced pediatric cancer on families. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2014;47: 594–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fladeboe K, King K, Kawamura J, et al. Featured Article: Caregiver Perceptions of Stress and Sibling Conflict During Pediatric Cancer Treatment. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2018;43: 588–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heath JA, Lintuuran RM, Rigguto G, Tokatlian N, McCarthy M. Childhood cancer: its impact and financial costs for Australian families. Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. 2006;23: 439–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yabroff KR, Zhao J, Zheng Z, Rai A, Han X. Medical Financial Hardship among Cancer Survivors in the United States: What Do We Know? What Do We Need to Know? Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention. 2018;27: 1389–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhao L, Portier K, Stein K, Baker F, Smith T. Exploratory factor analysis of the Cancer Problems in Living Scale: a report from the American Cancer Society’s Studies of Cancer Survivors. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2009;37: 676–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carver CS, Smith RG, Petronis VM, Antoni MH. Quality of life among long-term survivors of breast cancer: Different types of antecedents predict different classes of outcomes. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15: 749–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Head BA, Faul AC. Development and validation of a scale to measure socioeconomic well-being in persons with cancer. Journal of Supportive Oncology. 2008;6: 183–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Veenstra CM, Regenbogen SE, Hawley ST, et al. A composite measure of personal financial burden among patients with stage III colorectal cancer. Medical Care. 2014;52: 957–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.