Abstract

Satiation has been described as a process that leads to the termination of eating and controls meal size. However, studies have shown that the termination of eating can be influenced by multiple behavioral and biological processes over the course of a meal as well as those related to the context in which the meal is consumed. To expand understanding of how individuals experience satiation during a meal, we recently developed the Reasons Individuals Stop Eating Questionnaire (RISE-Q). The development of the RISE-Q revealed five distinct factors reported to contribute to meal termination: Planned Amount, Self-Consciousness, Decreased Food Appeal, Physical Satisfaction, and Decreased Priority of Eating. Thus, we define satiation as a series of dynamic processes that emerge over the course of a meal to promote meal termination. We suggest that each of the factors identified by the RISE-Q represents a distinct process, and illustrate the contribution of each process to meal termination in the Satiation Framework. Within this framework the prominence of each process as a reason to stop eating likely depends on meal context in addition to individual variability. Therefore, we discuss contexts in which different processes may be salient as determinants of meal termination. Expanding the definition of satiation to include several dynamic processes as illustrated in the Satiation Framework will help to stimulate investigation and understanding of the complex nature of meal termination.

Keywords: Satiation, Meal Termination, RISE-Q, Energy Intake, Meal Size

1. Introduction:

Satiation has been described as “the process that leads to the termination of eating and therefore controls meal size”1. While the primary focus has been on mechanisms that signal physical fullness2,3, recent work has shown that additional influences, including hedonic decline4, consuming a planned amount5, and social contexts,6 can also promote the termination of a meal. Therefore, we propose that satiation is a series of processes, including, but not limited to, physiological mechanisms that lead to meal termination. These processes are likely to vary between meals and other eating occasions such as snacks depending on what is eaten, where, and with whom. In this review, we discuss how food characteristics and the eating environment can influence the effect of each process on meal size and eating cessation.

Meal size (energy or weight consumed) as assessed by ad libitum food intake is the primary, objective measure of satiation7. In addition, changes in self-rated fullness across a meal serve as a proxy assessment of satiation. However, these measures alone do not address the multiple processes that contribute to the termination of eating. Recently, we developed the Reasons Individuals Stop Eating Questionnaire (RISE-Q), a tool to characterize satiation. The validation of the RISE-Q identified five distinct factors that represent different reasons for meal termination: Planned Amount (e.g. having eaten a pre-determined portion); Self-Consciousness (e.g. feeling embarrassed about the amount eaten); Physical Satisfaction (e.g. experiencing fullness); Decreased Food Appeal (e.g. the food no longer tasting good); and Decreased Priority of Eating (e.g. no longer being preoccupied with eating).

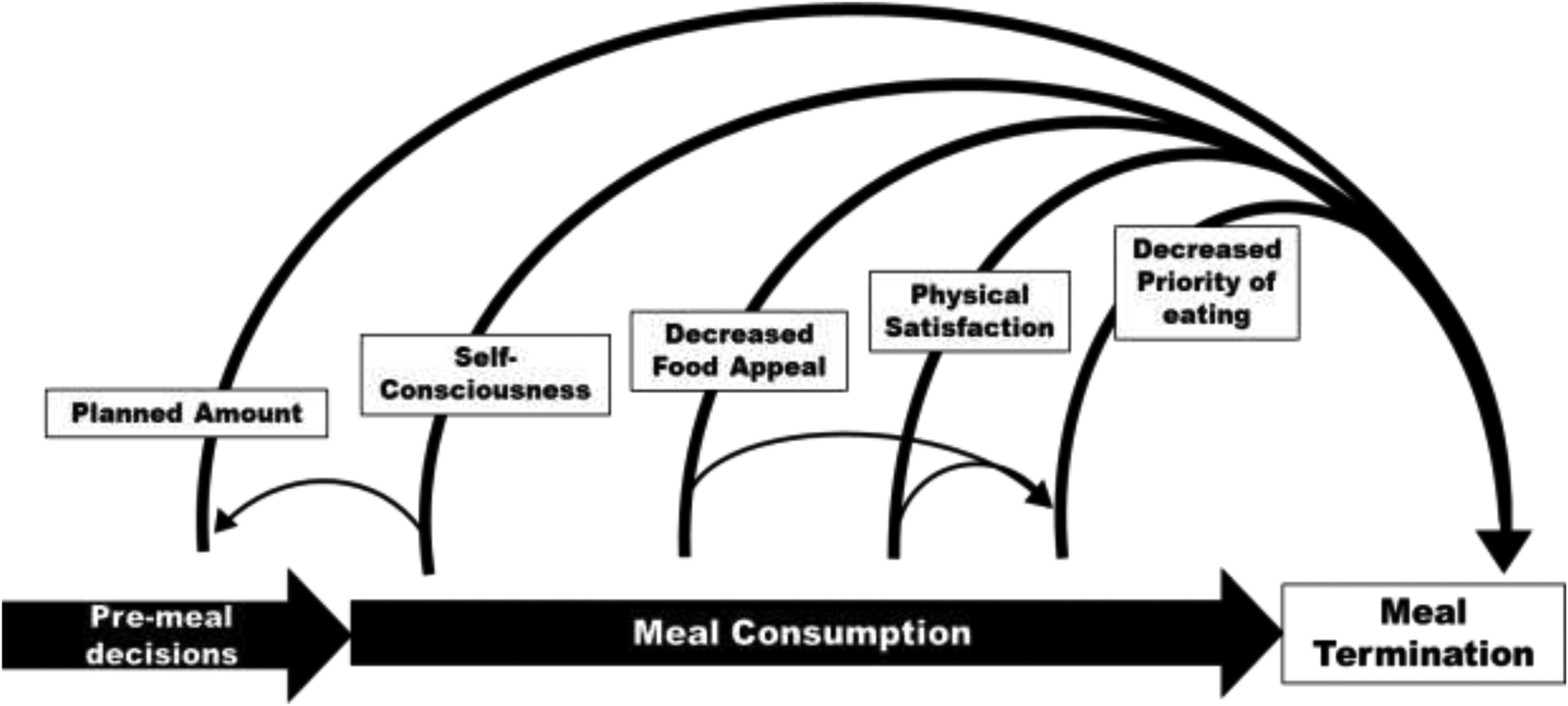

We have used the factors identified by the RISE-Q to more broadly inform our understanding of satiation, and suggest that each of the factors reflects a process involved in the termination of eating. The concept of satiation as a set of dynamic processes is illustrated by the Satiation Framework (see figure 1). Here we propose an extension of the well-known Satiety Cascade8 that presents the progression of signals contributing to inhibition of future eating (satiety). Although the Satiety Cascade includes satiation, it does not provide a framework for in-depth examination of the various processes that contribute to satiation.

Figure 1:

The Satiation Framework illustrates processes that contribute to the termination of a meal. The Framework can be used to conceptualize the complex nature of satiation, though the proposed time course of each process likely varies depending on food properties, meal context and individual characteristics.

The Satiation Framework illustrates various processes based on the factors identified by the RISE-Q that contribute to the termination of eating over the course of a meal. It is well established that decisions about what and how much to eat influence meal termination before the meal has begun (Planned Amount)9 and that social influences also affect pre-meal decisions (Self-Consciousness)6. Determining the time course of the other processes is more challenging since it requires continuous assessment as individuals eat. While past studies have measured subjective ratings such as hunger, fullness and palatability continuously during meals10–13 disrupting eating to make such measurements introduces potential issues with validity and demand characteristics. For instance, both Yeomans et al. (1997), and Griffioen-Roose et al. (2009) found that compared to uninterrupted meals, intake differed when individuals completed subjective ratings at regular intervals during the meal13,14.

The time course of each process is also likely to vary depending on food properties, meal context and individual characteristics. For instance, compared to high energy dense foods, those low in energy density provide more volume for energy and tend to be less palatable15. Volume and palatability can influence how quickly foods are consumed and oral exposure time16,17, which in turn likely affect the time course of these satiation processes18. In general, it might be expected that individuals are aware of the social context of the eating occasion from the outset, and this may influence eating behavior throughout the meal. Therefore, in the Satiation Framework we propose that the effects of Self-Consciousness are apparent early in a meal. Both the pleasantness of food (Decreased Food Appeal) and fullness (Physical Satisfaction) change over the course of the meal to promote meal termination4,19, and can in turn influence the extent to which eating is a priority. Thus, the proposed Satiation Framework illustrates the dynamic processes of satiation and how they progress towards meal termination.

Although the Satiation Framework illustrates each process in approximate order of its occurrence, it does not address the strength of the contribution of each process to meal termination. Indeed, the salience of each process likely varies between individuals and from meal to meal depending on context, properties of the food consumed, and other elements of the eating environment. In this review, we will explore the processes leading to meal termination with consideration of the circumstances that can influence the salience of each process in determining meal size.

Identifying why individuals stop eating with the RISE-Q

To develop the Reasons Individuals Stop Eating Questionnaire (RISE-Q)20 (see table 1), we searched the published literature for studies related to satiation in order to catalog different reasons that individuals might stop eating at a meal. These included stomach fullness, the food no longer tasting good, not wanting to overeat, or feeling embarrassed about the amount eaten. Based on our literature search, we created 47 items that represented the different reasons an individual might stop eating. Since context such as the type and location of meals can have an influence21, we specified that the context for the survey was a typical dinner meal at home. We asked participants to rate in that context how often each item was a reason they stopped eating. We administered the RISE-Q in an online survey to 477 individuals living in central Pennsylvania. After collecting responses, we conducted a factor analysis that revealed a reduced questionnaire consisting of 31 items that clustered into five overarching factors that drive meal termination: Planned Amount, Self-Consciousness, Decreased Food Appeal, Physical Satisfaction, and Decreased Priority of Eating.

Table 1:

The Reasons Individuals Stop Eating Questionnaire (RISE-Q)

| At a typical dinner meal eaten at home, I stop eating because… | |

|---|---|

| Decreased Food Appeal | The food no longer tastes good |

| The food is no longer appealing to me | |

| The food no longer looks good | |

| The food is no longer pleasant | |

| The food is no longer the right texture | |

| I am no longer interested in the food | |

| Only foods I don’t like are left | |

| The food no longer smells good | |

| The food is no longer the right temperature | |

| Physical Satisfaction | I no longer feel hungry |

| My stomach is full | |

| I have eaten an amount that usually satisfies me | |

| I am satisfied with the amount I have eaten | |

| The amount I have eaten matches my appetite | |

| I have eaten enough to keep me full for a while | |

| I have no desire to eat anything else | |

| Planned Amount | I have eaten the amount that I planned |

| I have eaten the amount that I served myself | |

| I have eaten a single serving | |

| I have eaten the amount I think is appropriate | |

| I have eaten the same amount that I usually eat | |

| I don’t want to overeat | |

| Self-Consciousness | I feel embarrassed about the amount I have eaten |

| I feel like I will be judged if I eat more | |

| I feel guilty about the amount I have eaten | |

| I have eaten more than others | |

| I want to eat the same amount as everyone else | |

| Priority of Eating | Eating no longer feels worth the effort |

| I have become restless | |

| I am no longer motivated to eat | |

| I am no longer thinking about food |

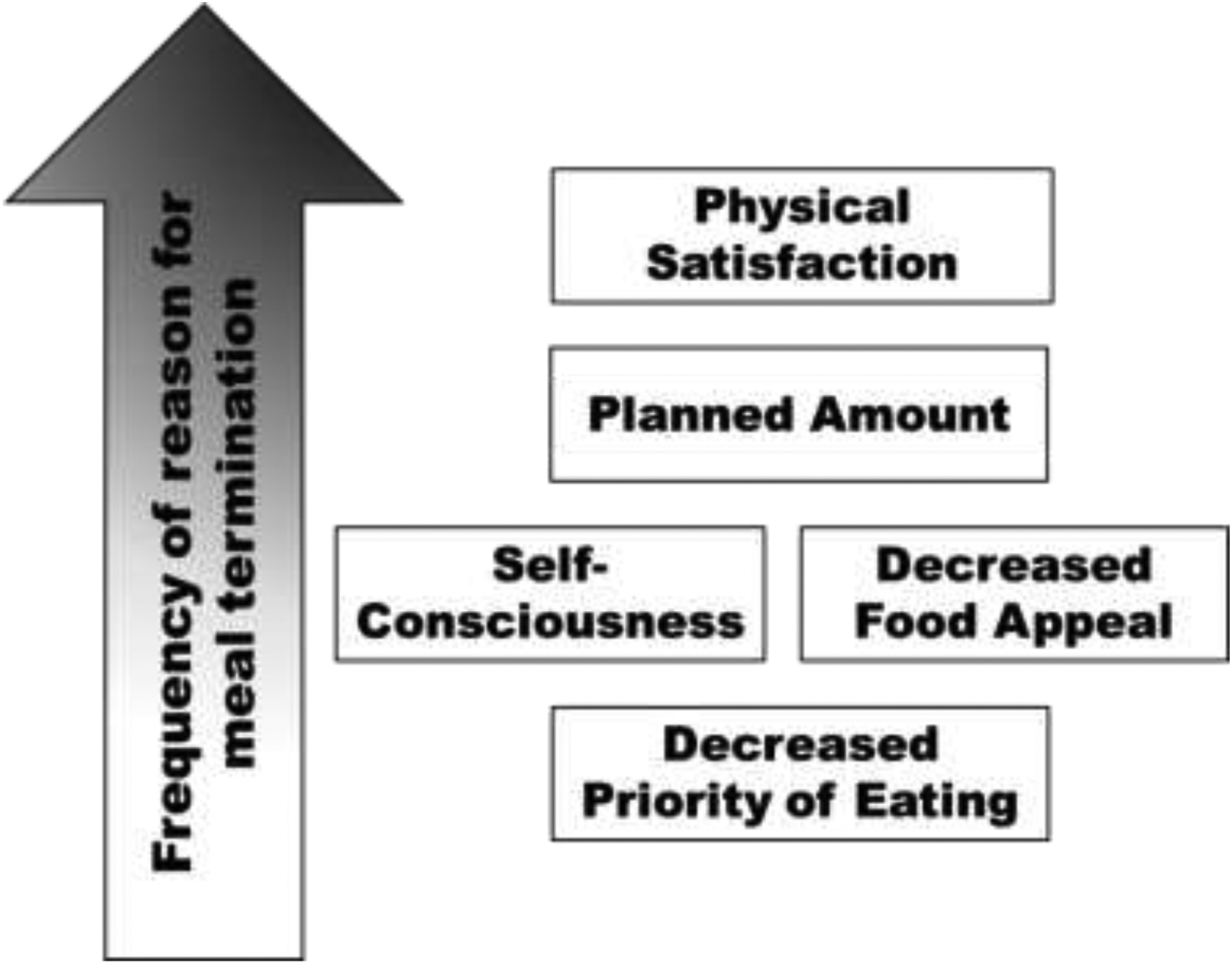

Individuals in our study reported experiencing Physical Satisfaction as the most frequent determinant of meal termination, followed by Planned Amount, Self-Consciousness and Decreased Food Appeal, and lastly Decreased Priority of Eating20 (see Figure 2). This is in line with previous studies finding that individuals reported physical fullness as a primary reason to stop eating22,23. The Satiation Framework illustrates how each of the RISE-Q factors corresponds to a process involved in satiation. We propose that the reported frequency of experiencing each RISE-Q factor could indicate the salience of its corresponding process in the context of the meal under investigation. For example, that the RISE-Q found that the factor of Physical Satisfaction was reported most often as a reason to stop eating at a dinner meal at home suggests that the process of Physical Satisfaction it is a relatively prominent driver of satiation in that context. Physical Satisfaction cannot, however, be assumed to predominantly determine meal termination under other circumstances.

Figure 2:

An illustration of how often each factor identified by the RISE-Q was reported as a reason to stop eating at a typical dinner meal at home. We found significant differences between factors such that Physical Satisfaction was reported most often, followed by Planned Amount, then Self-Consciousness and Decreased Food Appeal. Decreased Priority of Eating was reported the least often.

Reasons to stop eating are likely to vary depending on meal type (e.g. breakfast, snacks), context (e.g. home, restaurant, work cafeteria), properties of the available food (e.g. palatability, energy density, texture), and individual characteristics. Although we specified a dinner meal at home, the RISE-Q can be adapted and utilized to characterize satiation in a variety of contexts, and in broad and diverse populations. Further investigation of how each of the five processes contributes to satiation under various conditions can supplement more laborious and expensive laboratory studies that assess satiation in small populations, one or two variables at a time. Thus, the RISE-Q shows significant potential to expand understanding of satiation by assessing the extent to which each process contributes to meal termination in various contexts and populations.

2. Planned Amount

The processes leading to meal termination begin even before the first bite. Prior to the meal, when given the opportunity, individuals select the foods and amounts they plan to eat, and typically proceed to consume these portions, often in their entirety5,25,26. The RISE-Q factor of Planned Amount includes reasons to stop eating such as “I have eaten the amount that I planned”, and “I have eaten the amount that I served myself” (see table 1). At a typical dinner meal at home, we found that Planned Amount was the second most frequently reported factor driving meal termination20, indicating the process of Planned Amount was prominent in that context. This is in line with previous studies suggesting that having no food left can be a salient determinant of meal termination22,23,24, with Hardman and Rogers (2013) finding that it was the most frequently reported reason to stop eating23. Meal termination as a result of having no food left is likely to be related to Planned Amount, given the tendency of individuals to consume a planned meal in its entirety5,25,26.

The extent to which Planned Amount influences meal size depends on the properties of the available foods. When serving oneself, the amount selected and consumed varies with food palatability27, volume and energy density28, variety29, and portion size25,30, among other factors. For instance, Brunstrom and colleagues have explored the role of expectations of satiation (e.g. the extent to which a food is expected to confer fullness during eating) and satiety (e.g. the extent to which a food is expected to maintain fullness after eating) in pre-meal planning9,31. Over multiple eating occasions, individuals often learn to associate their experience of fullness with the food they have consumed32 and generally expect to reach similar levels of fullness when presented with this food, or foods with similar characteristics33. As a result, individuals might plan to consume smaller portions of foods that they anticipate will confer greater fullness9,31 such as those with thicker textures34 and larger volumes35. When individuals can serve their own foods, what and how much they eat can be influenced by properties of the foods, such as those that affect expected fullness.

Foods that are pre-portioned such as snacks and ready-to-eat meals can be perceived as an appropriate amount to consume in their entirety36. Therefore, consumption of these foods is likely largely determined by Planned Amount. Indeed, the Planned Amount factor in the RISE-Q includes statements such as “I have eaten a single serving” and “I have eaten the amount I think is appropriate”. In addition to food properties, social context plays a role in what and how much people plan to eat6,37. Although we found that Planned Amount was a prominent determinant of meal termination at a typical dinner meal at home, the role of Planned Amount would likely differ in other contexts such as restaurants where portion selection and pre-meal decisions are influenced more by others. The RISE-Q can be utilized to provide information about reasons for meal termination in a variety of contexts, including those with less opportunity for pre-meal planning.

3. Self-Consciousness

Not only is it common for individuals to plan their meal according to the people around them6,38, they may base an appropriate amount to eat on the amount other people consume39,40. The process of Self-Consciousness reflects meal termination as a result of social influences with its corresponding RISE-Q factor including reasons to stop eating such as “I want to eat the same amount as everyone else” (see table 1). Deviation from a perceived social norm such as eating more than other people can have negative emotional repercussions41. As such, Self-Consciousness also reflects meal termination resulting from negative feelings about the amount eaten, with the RISE-Q factor including stopping because “I feel embarrassed about the amount I have eaten”, and “I feel like I will be judged if I eat more”.

Much is known about social influences on eating, and it is well established that meal size is partly determined by the social context in which a meal is eaten37,42. For instance, when eating with someone who consumes a large portion, individuals eat more than when eating with someone who consumes a small portion43–47. Even in hunger states during which Physical Satisfaction might be expected to be the strongest determinant of meal termination, if individuals are in the presence of another person, they have been found to consume similar amounts to their companion48. However, this is moderated by the level of familiarity with the eating companion; individuals tend to eat more in the presence of familiar companions such as friends and family compared to strangers49,50. Thus, the influence of Self-Consciousness on meal termination is dependent on the meal’s social context.

In our initial investigation of the RISE-Q, we found that on average Self-Consciousness was only occasionally experienced as a reason to stop eating at a dinner meal at home. However, in that study, we did not specify social elements in the given context. Future adaptations of the RISE-Q could be used to explore the influence of social context on Self-Consciousness as a reason to stop eating. It is possible, for instance, that even in the same context of a dinner meal at home, specifying whether the meal is eaten alone or with other people would produce significantly different findings. Additionally, given that some meals are generally more social than others (e.g. dinner vs. lunch)51,52, the salience of Self-Consciousness as a reason to stop eating may be specific to the eating occasion.

Investigation of how social influences affect satiation is challenging, given that naturalistic contexts are difficult to replicate in a laboratory and field studies are demanding of time and resources. Both laboratory and field studies are also potentially confounded by participants’ awareness of being observed, which is likely to influence the experience of Self-Consciousness and its relation to meal size53. Thus, from a methodological standpoint, the RISE-Q would serve as a simple and practical tool to investigate the processes contributing to satiation in a variety of social contexts.

4. Decreased Food Appeal

The process of Decreased Food Appeal encompasses meal termination as a result of hedonic decline over the course of a meal, with its corresponding RISE-Q factor including reasons to stop eating such as “the food no longer tastes good” and “the food is no longer pleasant” (see table 1). The effect of hedonic decline on the termination of eating was explored in 1946 by Young, who observed that after pre-feeding rats with one food their preference for that food declined relative to other foods54, demonstrating that satiation was specific to the eaten food. In discussion of such early studies, Le Magnen coined the phrase “sensory specific satiety”55 (SSS), a term that we adopted when first demonstrating this phenomenon in humans4,56 and still use today. However, since hedonic decline promotes the termination of eating (satiation) more than the inhibition of future eating (satiety)57, we recognize that this phenomenon would more accurately be described as sensory-specific satiation. Meal termination driven by this sensory-specific response to eaten foods is captured by the process of Decreased Food Appeal.

The influence of Decreased Food Appeal on meal size can depend on the properties of the food being consumed. For instance, increasing food variety has been shown to delay the onset of sensory-specific satiety and increase food intake compared to less variety58,59. In one of our earlier studies, we found that intake of four successive courses of sandwiches varying in flavor was about one third greater than when the same flavor of sandwich was served for all four courses58. The effects of variety on sensory-specific satiety become more pronounced as variety increases and are greatest when foods differ in multiple sensory properties58. Moreover, studies using sham feeding methods have established that the mechanisms driving sensory-specific satiety occur as a result of oro-sensory exposure (the time food spends in the mouth)60,61. Therefore, the influence of Decreased Food Appeal on meal size may also be dependent on food properties that affect oro-sensory exposure, such as the volume of food consumed62.

In previous studies, Decreased Food Appeal has been less commonly reported by individuals as a reason for meal termination compared to other processes such as Physical Satisfaction22,23. In our RISE-Q study, we too found that individuals only occasionally reported it as a determinant of meal termination at dinner. However, Hetherington (1996) reported that at a test meal of cheese on crackers, reasons related to sensory-specific satiety were commonly reported to influence meal termination63. Thus, although Decreased Food Appeal may not be a primary reason to stop eating at a typical dinner meal at home, Hetherington’s (1996) findings suggest that for other eating occasions it can be more prominent. Recent evidence shows that activities that distract from eating, such as playing a computer game, diminish the role of Decreased Food Appeal64,65, further indicating that its prominence varies according to the eating environment. The RISE-Q can inform and supplement laboratory studies typically used to investigate the role of hedonic decline on meal termination by exploring the circumstances under which Decreased Food Appeal is a salient reason to stop eating.

5. Physical Satisfaction

When asked why they usually stop eating, people often state that they stopped because they were full22,23,24. Indeed, the sensation of fullness is familiar to most people, at least in the modern food environment, and is a salient signal for eating to stop. The process of Physical Satisfaction reflects meal termination resulting from reaching a satisfactory level of fullness. The Physical Satisfaction factor of the RISE-Q includes reasons to stop eating such as “I no longer feel hungry”, “my stomach is full”, and “the amount I have eaten matches my appetite” (see table 1). Controlled studies find that physical fullness is consistently reported to be the primary reason individuals give for why they stop eating22,23,24. We too found that the Physical Satisfaction factor of the RISE-Q was the most frequently reported reason to stop eating at a typical dinner meal at home20. However, as we have discussed, other processes contributing to satiation can have more prominence than Physical Satisfaction in certain situations. Self-Consciousness, for instance, can promote meal termination even more than Physical Satisfaction in social contexts48.

Physical satisfaction is promoted by biological responses to consumption, the details of which are beyond the scope of this review but which have been well documented in the literature66–68. As we eat, oro-sensory and gastric mechanisms are activated depending on factors such as how much time food spends in the mouth, the degree of gastric distention, and the rate of gastric emptying69–73. These processes can vary depending on what and how much we eat, such that foods with different nutrient profiles74, textures75,76, volumes77, energy densities15,78, and other properties can influence when individuals begin to feel full, how full they feel, and meal size18,69,79. Subjectively, people report that they experience hunger as aching and growling in the abdominal area, with some reports of dizziness and headaches80. Physical satisfaction is likely due in part to the reversal of these unpleasant sensations and this promotes the termination of eating.

Many studies, the RISE-Q included, have found that individuals report Physical Satisfaction as a salient reason for meal termination20,22,23. It is possible, however, that these reports are subject to misattribution. Individuals are not always aware of why they stopped eating, and there has been some suggestion that there is an explicit “disconnect between people’s beliefs about what influences their behavior and what actually influences their behavior”81. A common belief is that states of hunger and fullness dictate the amount we eat. Therefore, when individuals stop eating, they may assume that they did so as a result of fullness, despite other processes having a greater influence on satiation. The erroneous attribution of meal termination to assumed physical fullness may be attenuated when individuals are asked to consider the other processes that contribute to eating cessation. Broad consideration of the various processes contributing to satiation is aided by the RISE-Q, which provides 31 reasons to stop eating representing each of the five satiation processes. While providing a large number of potential responses may increase the likelihood of response bias, prompting reflection on various reasons to stop eating may allow the detection of processes contributing to meal termination that individuals would not have otherwise reported.

6. Decreased Priority of Eating

Eating is a motivated behavior that we engage in to obtain reward (e.g. pleasure, absence of hunger) so long as it is sufficiently rewarding to overcome associated expense (e.g. physical and cognitive effort, discomfort from fullness, time, and cost). With respect to satiation, when motivation to eat decreases, such as when the reward value of food decreases or the expense increases, individuals will stop eating82. The process of Decreased Priority of Eating reflects this decline in motivation to eat, with its corresponding RISE-Q factor including reasons to stop eating such as “I am no longer motivated to eat” and “eating no longer feels worth the effort” (see table 1).

As illustrated in the Satiation Framework (Figure 1), Decreased Priority of Eating is related to both Physical Satisfaction and Decreased Food Appeal. People lose motivation to eat when they reach fullness or when food is no longer hedonically rewarding83. Thus, elements of the food environment that promote Physical Satisfaction or Decreased Food Appeal are likely also to contribute to Decreased Priority of Eating. Research using the reinforcing value of food paradigm has explored meal termination as a result of Decreased Priority of Eating. This paradigm evaluates willingness to expend effort to obtain a reward such as food and has been described as an “index of motivation to eat”84. Higher food reinforcement has been related to greater energy intake85, and foods that are more reinforcing, such as those that are highly palatable86, may influence meal size by delaying the decline in motivation to eat.

Research investigating the relative reinforcing value of food further suggests that satiation is influenced not only by motivation to eat, but specifically motivation to eat rather than do something else87,88. For instance, some individuals might stop eating so that they can instead engage in video games or attend a social event. This is not necessarily because the food is not reinforcing, but because it is less reinforcing than an alternative. Here context plays a role in determining the influence of Decreased Priority of Eating on meal size. In our initial development of the RISE-Q, we included items pertaining to contextual factors that could promote meal termination. For example, the initial 47-item questionnaire included reasons to stop eating such as not having time to eat more, and stopping when something else demands attention. Although these reasons did not reach statistical cutoffs for inclusion in the final questionnaire, they present relevant examples of contextual distractions that can influence Decreased Priority of Eating. The numerous situation-specific influences on Decreased Priority of Eating are difficult to capture in laboratory studies. Thus, the RISE-Q can be utilized to help explore the prevalence of Decreased Priority of Eating in contexts where it is likely to contribute to satiation, such as when individuals have limited time or eat meals concurrently with distractions.

7. Conclusions

Although much is known about factors that influence satiation, fundamental questions remain, including those related to context and individual variability. In this review, we propose the Satiation Framework which illustrates processes based on factors identified by the RISE-Q that contribute to the termination of eating over the course of a meal. The prominence of each process as a determinant of meal termination varies from meal to meal depending on who is eating as well as where, when, and what they are eating. The assessment of the contribution of these various processes should not rely entirely on controlled laboratory studies, not only because of limited ecological validity and demand characteristics, but also due to time and cost restraints. The Reasons Individuals Stop Eating Questionnaire (RISE-Q) provides a validated and easily administered instrument to assess individuals’ experience of the processes driving meal termination in a variety of situations.

Although the RISE-Q has potential utility for understanding satiation, limitations of the questionnaire should be noted. As with all self-report measures, the RISE-Q is subject to demand characteristics and other response biases. We have discussed in this review that individuals are not always aware of why they stopped eating81 and some factors may be easier to recognize than others. Indeed, subjective reports of sensations such as fullness do not always concur with objective measures79. Establishing the degree of discordance between perceptions of why individuals stop eating and objective drivers of meal termination will be beneficial. Investigation of how the RISE-Q factors are associated with intake and related measures such as eating rate will help to further validate the RISE-Q and provide insight into the nature of satiation.

The Satiation Framework we have proposed begins to explore how satiation processes are related. The salience of each process at a given eating occasion may influence the salience of other processes. For example, at meals in which Physical Satisfaction is a strong determinant of meal termination, Planned Amount or Self-Consciousness may contribute less. The processes of Decreased Food Appeal, Physical Satisfaction, and Decreased Priority of Eating in particular are likely to be highly related and may work together to drive eating cessation. Future research should explore the relationships between the various processes and how they influence meal termination to improve understanding of the determinants of food intake.

In our initial exploration of the RISE-Q, we specified the context of a typical dinner meal at home. Future adaptations of the questionnaire should explore other variables such as the social setting and the properties of the available food in order to assess the drivers of meal termination in various contexts. Development and validation of a shorter version of the questionnaire could provide a tool that can be used in obesity treatment and behavioral weight loss interventions to help understand why patients overeat. Furthermore, satiation can vary between individuals depending on characteristics such as food insecurity, interoceptive awareness, and dietary restraint. For instance, individuals with high interoceptive awareness might be expected to stop eating primarily as a result of Physical Satisfaction, while individuals who have high dietary restraint may terminate eating as a result of consuming a Planned Amount or Self-Consciousness. The RISE-Q along with other standard instruments such as the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire89 can aid future investigations of differences in satiation depending on individual characteristics. Expanding the definition of satiation to include several dynamic processes as illustrated in the Satiation Framework will help to stimulate investigation and understanding of the complex nature of meal termination.

Highlights:

The Reasons Individuals Stop Eating Questionnaire (RISE-Q) characterizes satiation

The RISE-Q identified factors that represent processes that contribute to satiation

The Satiation Framework depicts various processes leading to meal termination

The salience of these processes depends on context and food properties

The Satiation Framework will aid understanding of the nature of meal termination

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant R01-DK082580 to BJR), and the Ruth L. Pike Nutritional Sciences Graduate Fellowship (to PMC). The sponsors had no role in any aspects of the original research described in this review nor in the interpretation of data or conclusions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Blundell J, de Graaf C, Hulshof T, et al. Appetite control: Methodological aspects of the evaluation of foods. Obes Rev Off J Int Assoc Study Obes. 2010;11(3):251–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-89X.2010.00714.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hopkins M, Blundell J, Halford J, King N, Finlayson G. The Regulation of Food Intake in Humans. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al. , eds. Endotext. MDText.com, Inc.; 2000. Accessed March 17, 2021. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK278931/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benelam B. Satiation, satiety and their effects on eating behaviour. Nutr Bull. 2009;34(2):126–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-3010.2009.01753.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rolls B, Rolls E, Rowe E, Sweeney K. Sensory specific satiety in man. Physiol Behav. 1981;27(1):137–142. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(81)90310-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fay SH, Ferriday D, Hinton EC, Shakeshaft NG, Rogers PJ, Brunstrom JM. What determines real-world meal size? Evidence for pre-meal planning. Appetite. 2011;56(2):284–289. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgs S. Social norms and their influence on eating behaviours. Appetite. 2015;86:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forde CG. Measuring Satiation and Satiety. In: Ares G, Varela P, eds. Methods in Consumer Research. Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition. Woodhead Publishing; 2018:151–182. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-101743-2.00007-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellisle F, Blundell JE. Satiation, Satiety: Concepts and Organisation of Behaviour. In: Blundell JE, Bellisle F, eds. Satiation, Satiety and the Control of Food Intake. Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition. Woodhead Publishing; 2013:3–11. doi: 10.1533/9780857098719.1.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunstrom JM. Mind over platter: pre-meal planning and the control of meal size in humans. Int J Obes. 2014;38(1):S9–S12. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hinton EC, Leary SD, Comlek L, Rogers PJ, Hamilton-Shield JP. How full am I? The effect of rating fullness during eating on food intake, eating speed and relationship with satiety responsiveness. Appetite. 2021;157:104998. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.104998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sysko R, Devlin MJ, Walsh BT, Zimmerli E, Kissileff HR. Satiety and test meal intake among women with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(6):554–561. doi: 10.1002/eat.20384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samuels F, Zimmerli EJ, Devlin MJ, Kissileff HR, Walsh BT. The development of hunger and fullness during a laboratory meal in patients with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42(2):125–129. doi: 10.1002/eat.20585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeomans MR, Gray RW, Mitchell CJ, True S. Independent effects of palatability and within-meal pauses on intake and appetite ratings in human volunteers. Appetite. 1997;29(1):61–76. doi: 10.1006/appe.1997.0092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffioen-Roose S, Mars M, Finlayson G, Blundell JE, de Graaf C. Satiation due to equally palatable sweet and savory meals does not differ in normal weight young adults. J Nutr. 2009;139(11):2093–2098. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.110924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rolls BJ. The relationship between dietary energy density and energy intake. Physiol Behav. 2009;97(5):609–615. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wijlens AGM, Erkner A, Alexander E, Mars M, Smeets PAM, Graaf C de. Effects of oral and gastric stimulation on appetite and energy intake. Obesity. 2012;20(11):2226–2232. doi: 10.1038/oby.2012.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeomans MR. Palatability and the micro-structure of feeding in humans: the Appetizer Effect. Appetite. 1996;27(2):119–133. doi: 10.1006/appe.1996.0040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bolhuis DP, Lakemond CMM, de Wijk RA, Luning PA, de Graaf C. Both longer oral sensory exposure to and higher intensity of saltiness decrease ad libitum food intake in healthy normal-weight men. J Nutr. 2011;141(12):2242–2248. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.143867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill AJ, Magson LD, Blundell JE. Hunger and palatability: Tracking ratings of subjective experience before, during and after the consumption of preferred and less preferred food. Appetite. 1984;5(4):361–371. doi: 10.1016/S0195-6663(84)80008-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cunningham PM, Roe LS, Hayes JE, Hetherington MM, Keller KL, Rolls BJ. Development and validation of the Reasons Individuals Stop Eating Questionnaire (RISE-Q): A novel measure to characterize satiation. Appetite. 2021; 161:105127. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meiselman HL. The Role of Context in Food Choice, Food Acceptance and Food Consumption. In: Shepherd R, Raats M, eds. The Psychology of Food Choice. Frontiers in Nutritional Science Issue 3. CABI; 2006. doi: 10.1079/9780851990323.0179 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mook DG, Votaw MC. How important is hedonism? Reasons given by college students for ending a meal. Appetite. 1992;18(1):69–75. doi: 10.1016/0195-6663(92)90211-N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hardman CA, Rogers PJ. “The food is all gone”. Reasons given by university students for ending a meal. A replication and new data. Appetite. 2013;71:477. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.06.031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tuomisto T, Tuomisto M, Hetherington M, Lappalainen R. Reasons for initiation and cessation of eating in obese men and women and the affective consequences of eating in everyday situations. Appetite. 1998;30(2):211–222. doi: 10.1006/appe.1997.0142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robinson E, te Raa W, Hardman CA. Portion size and intended consumption. Evidence for a pre-consumption portion size effect in males? Appetite. 2015;91:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hinton EC, Brunstrom JM, Fay SH, et al. Using photography in ‘The Restaurant of the Future’. A useful way to assess portion selection and plate cleaning? Appetite. 2013;63:31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brunstrom JM, Shakeshaft NG. Measuring affective (liking) and non-affective (expected satiety) determinants of portion size and food reward. Appetite. 2009;52(1):108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunstrom JM, Shakeshaft NG, Scott-Samuel NE. Measuring ‘expected satiety’ in a range of common foods using a method of constant stimuli. Appetite. 2008;51(3):604–614. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilkinson LL, Hinton EC, Fay SH, Rogers PJ, Brunstrom JM. The ‘variety effect’ is anticipated in meal planning. Appetite. 2013;60:175–179. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cahayadi J, Geng X, Mirosa M, Peng M. Expectancy versus experience – Comparing Portion-Size-Effect during pre-meal planning and actual intake. Appetite. 2019;135:108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2019.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brunstrom JM. The control of meal size in human subjects: a role for expected satiety, expected satiation and premeal planning. Proc Nutr Soc. 2011;70(2):155–161. doi: 10.1017/S002966511000491X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brunstrom JM. The role of learning in expected satiety and decisions about portion size. Appetite. 2008;51(2):356. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.04.047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCrickerd K, Lensing N, Yeomans MR. The impact of food and beverage characteristics on expectations of satiation, satiety and thirst. Food Qual Prefer. 2015;44:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2015.04.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hogenkamp PS, Stafleu A, Mars M, Brunstrom JM, de Graaf C. Texture, not flavor, determines expected satiation of dairy products. Appetite. 2011;57(3):635–641. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brunstrom JM, Collingwood J, Rogers PJ. Perceived volume, expected satiation, and the energy content of self-selected meals. Appetite. 2010;55(1):25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geier AB, Rozin P, Doros G. Unit Bias: A new heuristic that helps explain the effect of portion size on food Intake. Psychol Sci. 2006;17(6):521–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01738.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higgs S, Ruddock H. Social Influences on Eating. In: Handbook of Eating and Drinking. Springer; 2020:277–291. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herman CP. The social facilitation of eating. A review. Appetite. 2015;86:61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herman CP, Roth DA, Polivy J. Effects of the presence of others on food intake: A normative interpretation. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(6):873–886. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herman CP, Koenig-Nobert S, Peterson JB, Polivy J. Matching effects on eating: Do individual differences make a difference? Appetite. 2005;45(2):108–109. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2005.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baumeister RF. The Self. In: Advanced Social Psychology: The State of the Science. Oxford University Press; 2010:139–175. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Herman CP. The social facilitation of eating or the facilitation of social eating? J Eat Disord. 2017;5(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s40337-017-0146-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Polivy J, Herman CP, Younger JC, Erskine B. Effects of a model on eating behavior: The induction of a restrained eating style1. J Pers. 1979;47(1):100–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1979.tb00617.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenthal B, Marx RD. Modeling influences on the eating behavior of successful and unsuccessful dieters and untreated normal weight individuals. Addict Behav. 1979;4(3):215–221. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(79)90030-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenthal B, McSweeney FK. Modeling influences on eating behavior. Addict Behav. 1979;4(3):205–214. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(79)90029-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Conger JC, Conger AJ, Costanzo PR, Wright KL, Matter JA. The effect of social cues on the eating behavior of obese and normal subjects. J Pers. 1980;48(2):258–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1980.tb00832.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nisbett RE, Storms MD. Cognitive and Social Determinants of Food Intake. In: Nisbett RE eds. Thought and Feeling: Cognitive Alteration of Feeling States. Routledge; 2017. doi: 10.4324/9781315135656-19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goldman SJ, Herman CP, Polivy J. Is the effect of a social model on eating attenuated by hunger? Appetite. 1991;17(2):129–140. doi: 10.1016/0195-6663(91)90068-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clendenen VI, Herman CP, Polivy J. Social facilitation of eating among friends and strangers. Appetite. 1994;23(1):1–13. doi: 10.1006/appe.1994.1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Castro JM. Family and friends produce greater social facilitation of food intake than other companions. Physiol Behav. 1994;56(3):445–455. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90286-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dunbar RIM. Breaking bread: The functions of social eating. Adapt Hum Behav Physiol. 2017;3(3):198–211. doi: 10.1007/s40750-017-0061-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cruwys T, Bevelander KE, Hermans RCJ. Social modeling of eating: a review of when and why social influence affects food intake and choice. Appetite. 2015;86:3–18. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.08.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robinson E, Kersbergen I, Brunstrom JM, Field M. I’m watching you. Awareness that food consumption is being monitored is a demand characteristic in eating-behaviour experiments. Appetite. 2014;83:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Young P. Studies of food preference, appetite and dietary habit: VI. habit, palatability and the diet as factors regulating the selection of food by the rat. J Comp Psychol. 1946;39:139–176. doi: 10.1037/h0060087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Le Magnen J. Habits and Food Intake. In: Charles F, eds. Handbook of Physiology. Alimentary Canal, Vol 1. American Physiological Society; 1967:11–30. 10.1113/expphysiol.1969.sp002010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rolls BJ. Sensory-specific satiety. Nutr Rev. 1986;44(3):93–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1986.tb07593.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hetherington M, Rolls BJ, Burley VJ. The time course of sensory-specific satiety. Appetite. 1989;12(1):57–68. doi: 10.1016/0195-6663(89)90068-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rolls BJ, Rowe EA, Rolls ET, Kingston B, Megson A, Gunary R. Variety in a meal enhances food intake in man. Physiol Behav. 1981;26(2):215–221. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(81)90014-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brondel L, Romer M, Van Wymelbeke V, et al. Variety enhances food intake in humans: Role of sensory-specific satiety. Physiol Behav. 2009;97(1):44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nolan LJ, Hetherington MM. The effects of sham feeding-induced sensory specific satiation and food variety on subsequent food intake in humans. Appetite. 2009;52(3):720–725. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smeets AJPG, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Oral exposure and sensory-specific satiety. Physiol Behav. 2006;89(2):281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bell EA, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. Sensory-specific satiety is affected more by volume than by energy content of a liquid food. Physiol Behav. 2003;78(4):593–600. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(03)00055-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hetherington MM. Sensory-specific satiety and its importance in meal termination. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1996;20(1):113–117. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(95)00048-J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brunstrom JM, Mitchell GL. Effects of distraction on the development of satiety. Br J Nutr. 2006;96(4):761–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rogers PJ, Drumgoole FDY, Quinlan E, Thompson Y. An analysis of sensory-specific satiation: Food liking, food wanting, and the effects of distraction. Learn Motiv. 2021;73:101688. doi: 10.1016/j.lmot.2020.101688 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moran T, Ladenheim EE. Physiologic and neural controls of eating. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2016; 45(4): 581–599. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2016.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Camilleri M. Peripheral mechanisms in appetite regulation. Gastroenterology. 2015; 148(6): 1219–1233. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Woods SC. The control of food intake: Behavioral versus molecular perspectives. Cell Metab. 2009;9(6):489–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Woods SC. Gastrointestinal Satiety Signals I. An overview of gastrointestinal signals that influence food intake. Am J Physiol-Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286(1):G7–G13. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00448.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cummings DE, Overduin J. Gastrointestinal regulation of food intake. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(1):13–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI30227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cecil JE, Francis J, Read NW. Relative contributions of intestinal, gastric, oro-sensory Influences and information to changes in appetite induced by the same liquid meal. Appetite. 1998;31(3):377–390. doi: 10.1006/appe.1998.0177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.French SJ, Cecil JE. Oral, gastric and intestinal influences on human feeding. Physiol Behav. 2001;74(4):729–734. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(01)00617-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lasschuijt M, Mars M, de Graaf C, Smeets PAM. How oro-sensory exposure and eating rate affect satiation and associated endocrine responses—a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;111(6):1137–1149. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ritter RC. Gastrointestinal mechanisms of satiation for food. Physiol Behav. 2004;81(2):249–273. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Collins PJ, Horowitz M, Maddox A, Myers JC, Chatterton BE. Effects of increasing solid component size of a mixed solid/liquid meal on solid and liquid gastric emptying. Am J Physiol-Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1996;271(4):G549–G554. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.271.4.G549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ziessman HA, Chander A, Clarke JO, Ramos AL, Wahl R. The added diagnostic value of liquid gastric emptying compared with solid emptying alone. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(5):726–731. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.059790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Powley TL, Phillips RJ. Gastric satiation is volumetric, intestinal satiation is nutritive. Physiol Behav. 2004;82(1):69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.04.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hunt JN, Smith JL, Jiang CL. Effect of meal volume and energy density on the gastric emptying of carbohydrates. Gastroenterology. 1985;89(6):1326–1330. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90650-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Camps G, Mars M, de Graaf C, Smeets PA. Empty calories and phantom fullness: a randomized trial studying the relative effects of energy density and viscosity on gastric emptying determined by MRI and satiety. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104(1):73–80. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.129064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Friedman MI, Ulrich P, Mattes RD. A figurative measure of subjective hunger sensations. Appetite. 1999;32(3):395–404. doi: 10.1006/appe.1999.0230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Herman CP, Polivy J, Pliner P, Vartanian LR. Awareness of Social Cues. In: Herman CP, Polivy J, Pliner P, Vartanian LR, eds. Social Influences on Eating. Springer International Publishing; 2019:201–213. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-28817-4_12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Geiselman PJ. Control of food intake: A physiologically complex, motivated behavioral system. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1996;25(4):815–829. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8529(05)70356-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rogers PJ, Hardman CA. Food reward. What it is and how to measure it. Appetite. 2015;90:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.02.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Temple JL, Legierski CM, Giacomelli AM, Salvy S-J, Epstein LH. Overweight children find food more reinforcing and consume more energy than do nonoverweight children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(5):1121–1127. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Epstein LH, Temple JL, Neaderhiser BJ, Salis RJ, Erbe RW, Leddy JJ. Food reinforcement, the dopamine D2 receptor genotype, and energy intake in obese and nonobese humans. Behav Neurosci. 2007;121(5):877–886. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.5.877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Epstein LH, Leddy JJ. Food reinforcement. Appetite. 2006;46(1):22–25. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2005.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Epstein LH, Salvy SJ, Carr KA, Dearing KK, Bickel WK. Food reinforcement, delay discounting and obesity. Physiol Behav. 2010;100(5):438–445. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.04.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Carr KA, Epstein LH. Choice is relative: Reinforcing value of food and activity in obesity treatment. Am Psychol. 2020;75(2):139–151. doi: 10.1037/amp0000521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29(1):71–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90010-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]