Abstract

In addition to chronic infection with human papilloma virus (HPV) and exposure to environmental carcinogens, genetic and epigenetic factors act as major risk factors for head and neck cancer (HNC) development and progression. Here, we conducted a systematic review in order to assess whether DNA hypermethylated genes are predictive of high risk of developing HNC and/or impact on survival and outcomes in non-HPV/non-tobacco/non-alcohol associated HNC. We identified 85 studies covering 32,187 subjects where the relationship between DNA methylation, risk factors and survival outcomes were addressed. Changes in DNA hypermethylation were identified for 120 genes. Interactome analysis revealed enrichment in complex regulatory pathways that coordinate cell cycle progression (CCNA1, SFN, ATM, GADD45A, CDK2NA, TP53, RB1 and RASSF1). However, not all these genes showed significant statistical association with alcohol consumption, tobacco and/or HPV infection in the multivariate analysis. Genes with the most robust HNC risk association included TIMP3, DCC, DAPK, CDH1, CCNA1, MGMT, P16, MINT31, CD44, RARβ. From these candidates, we further validated CD44 at translational level in an independent cohort of 100 patients with tongue cancer followed-up beyond 10 years. CD44 expression was associated with high-risk of tumor recurrence and metastasis (P = 0.01) in HPV-cases. In summary, genes regulated by methylation play a modulatory function in HNC susceptibility and it represent a critical therapeutic target to manage patients with advanced disease.

Subject terms: Cancer, Predictive markers

Introduction

Head and neck cancer (HNC), the 6th common cancer worldwide, is characterized by high incidence of local tumor invasion and metastatic spread1,2. Despite of the advances in diagnosis and treatment modalities, high mortality rates rank HNC among the most aggressive cancers. This aggressiveness is contributed by the high loco-regional relapse seen at early stages, which is worsened by the heterogeneous nature of the disease involving a variety of histological tumor subtypes and affecting diverse anatomical sites3. Historically, the traditional risk factors for HNC include excessive tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, and infection by human papillomavirus (HPV). Additional factors have been identified to enhance individual susceptibility to HNC, in particular, genetic abnormalities impacting on cell proliferation, differentiation features, cell cycle checkpoints, angiogenesis and tumor metabolism4–8. Furthermore, deregulation of epigenetic machinery such as DNA methylation, nucleosome positioning, histone modifications and non-coding RNAs have been reported to contribute to enhanced individual susceptibility to HNC with direct influence on gene activities9.

DNA methylation is the major epigenetic alteration characterized by addition or removal of a methyl group (CH3) referred as hypermethylation of the CpG islands or global hypomethylation, respectively10. DNA hypomethylation has been associated with chromosomal instability as well as activation of proto-oncogenes, while DNA hypermethylation has been involved in repressing tumor suppressor genes and genomic instability often impacting on tumor initiation and progression9,10. The reversible nature of epigenetic aberrations has led to the promising benefit of epigenetic therapy for cancer prevention and management11. However, DNA methylation status vary according HNC subtypes, differentiation features, anatomic involvement12,13, HPV status14, smoking habits9 and geographic distribution15. Therefore, identifying crucial genes that are susceptible to DNA hypermethylation-induced gene silencing is becoming critical to tailor the utility of methylation modifiers to individual cancer types.

Here, we systematically reviewed published papers addressing epigenetic alterations, particularly DNA hypermethylation, in relation to individual susceptibility to HNC, as well as HNC progression and prognosis. We confirmed using a multivariate analysis the clinical relevance of 10 most common alterations as independent risk factors for HNC progression. Furthermore, we used a network-based analysis to prioritize putative molecular interactions and validate the candidates by protein expression in a cohort of HNC with long-term follow-up. Last, we discussed the potential of relevant FDA-approved drugs as alternative therapeutics for invasive HNC.

Materials and methods

Data search

The study followed the protocol recommended by Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (https://training.cochrane.org). In brief, we conducted this systematic literature review using online platforms: PubMed, Wiley Online Library, EMBASE, Web of Science, Scopus, and Cochrane databases between January 2008 and June 2020. The tested hypothesis was to establish the associations between epigenetic alteration and HNC risk. The search strategy focused on key words including their abbreviation, truncations, synonyms, and subsets for search, such as: “head and neck neoplasms” or “facial neoplasms” or “head and neck cancer” or “oral cancer” or “tongue cancer” or “mouth cancer” or the codes described in the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O) for Head and Neck Tumors (https://www.who.int); and “epigenetics” or “epigenomics” or “methylation” or “histone modification” or “non-coding RNA” or “ncRNA” and “risk factors” or “smoke” or "tobacco" or “alcohol” or “HPV”. Searches in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and ArrayExpress (www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress) repositories were also performed. We designed this strategy for a sensitive and broad search (Fig. 1). Additional relevant studies from the reference lists were also included in the analysis. Two librarian experts in systematic review methods hand searched the references list to find additional articles.

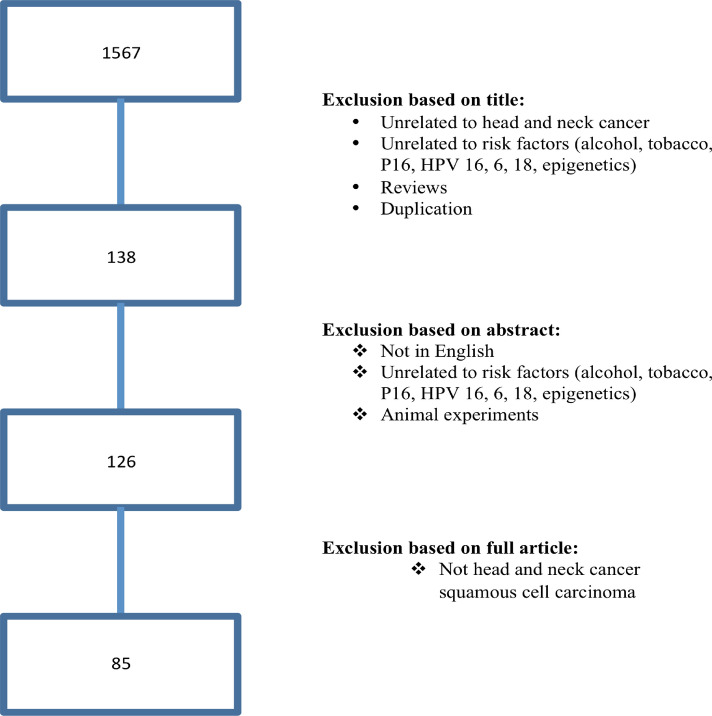

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of search and study selection process. Following the guidelines of the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology group (MOOSE), we performed a broad and sensitive search on online databases to identify the studies that examined associations between DNA methylation and HNC associated with risk factors (alcohol, tobacco and HPV infection). A systematic literature search for relevant studies up to June 2020. In this study, we considered the clinical endpoints overall survival (OS) and disease specific survival (DFS) as acceptable outcomes. The prognostic value was demonstrated using hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This study did not include non-English manuscripts, single case reports, editorial letters, and reviews of literature. It was also excluded cross-sectional studies that addressed associations with alcohol, tobacco and HPV status without specifically examining associations with epigenetic alteration. Studies using only preclinical models were also excluded. Then, the following inclusion criteria were required to be eligible in this systematic review: (1) human case–control studies; (2) clinical studies related to the DNA methylation and HNC risk factors; (3) methylation sequencing and array methods were excluded; 4) when the same research group was identified, publications were further investigated to eliminate duplications or samples overlap. The outcomes were further explored considering Hazard ratio (HR) with confidence of interval (CI) and P value < 0.05. Papers that fulfilled these criteria were processed for data extraction and the discrepancies were solved by discussion.

Data extraction and quality assessment

A standardized form adapted from Dutch Cochrane Centre (https://netherlands.cochrane.org) for epidemiological studies was used to extracted the date and its included: (a) clear definition of risk factors (alcohol, tobacco and HPV status); (b) clear definition of the molecular assay used for the measurement of epigenetic alteration (e.g. quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), methylation-specific PCR (MSP); (c) clear definition of cut-off, (d) definition of the anatomical site; e) definition of the target population (country where the study took place). To be qualified, all the criteria had to be mentioned in the manuscript; otherwise, the study was recorded and excluded from the systematic review.

In detail, data extracted from the final eligible articles include: first author, year of publication, impact factor of the journal publication, the country of origin, study design, population studied, subjects’ ethnicity, the number of cases, cancer types, source of control, epigenetic profiling, specimen, anatomic location, risk, HR and follow-up. The methodological quality and risk of bias was assessed by the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies 2 (QUADAS-2) score system.

Network and enrichment analyses

The list of epigenetic alterations, focusing on DNA hypermethylation, was submitted to GSEA to search for enriched biological processes (Gene Onology) and cellular pathways (KEGG) using FDR < 0.05 or top 50 as parameters16,17. The SIGnaling Network Open Resource 2.0 (SIGNOR 2.0), a public repository that stores almost 23,000 manually annotated causal relationships between proteins and other biologically relevant entities (chemicals, phenotypes, complexes and others) was used to construct a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network using all types of interactions and score 0.1 as parameters18.

Validation—study population

A retrospective study was performed by analyzing data from 100 patients with primary HNC diagnosed and treated at the Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Cancer at the Jewish General Hospital (McGill University) (Supplementary Table 1). The eligibility criteria included previously untreated patients with diagnosis of HNC submitted to the treatment in a single institution. This study was carried out with the approval of the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Jewish General Hospital (JGH)—McGill University, Canada (protocol#11–093) and informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies (STROBE Statement) was used to ensure appropriate methodological guidelines and regulations.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis

IHC reaction and analysis were carried out as we previously described19. In brief, the incubations with the primary antibody anti-CD44 (Dako, 1:100) diluted in PBS were made overnight at 4 °C. Positive and negative controls were included in all reactions. IHC reactions were performed in duplicates to represent different levels tissues levels in the same lesion. The second slide was 25–30 sections deeper than the first slide, resulting in a minimum of 300 µm distance between sections representing fourfold redundancy with different cell populations for each tissue. IHC scoring was blinded to the outcome and clinical aspects of the patients. Cores were scanned in 10× power field to settle on the foremost to marked area predominant in a minimum of 10% of the neoplasia. IHC reaction was considered as positive if of a clearly visible dark brown precipitation occurred. IHC analysis was semi-quantitative considering the percentage and intensity of staining as: 0 (no detectable reaction or little staining in < 10% of cells), 1 (weak but positive IHC expression in > 10% of cells) and 2 (strong positivity in > 10% of cells). The percentage of CD44 positive was calculated with an image computer analyzer (Kontron 400, Carl Zeiss, Germany)19.

Data analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using the STATA 12.0 statistical software (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) as we previously described19. The pooled parameters sensitivity, specificity, diagnostic hazard ratio (HR), and their 95% CIs were calculated to evaluate the overall diagnostic accuracy and the correlation between IHC status and HNC comparing high and low-risk patients. Statistical analysis considered the weighted effect, and the effect size was adjusted.

Results

Overview of the included studies

Following the search protocol and screening strategy, it was identified 1567 manuscripts. After exclusion of duplicates studies and manuscripts unrelated to epigenetic alteration or cancer, and reviews, 138 articles were retrieved for the title and abstract. Additional 12 studies were excluded, since they were either only abstracts or irrelevant to risk factors in HNC, leaving 126 studies for further full-text analysis (Fig. 1)19–103. Titles and abstracts retrieved through this search were screened by three of the authors (JH, OV, AB) and after a careful reading of the texts, 41 studies were removed due to the lack of information regarding survival analysis. Finally, we had 85 studies involving 32,187 subjects where the relationship between DNA hypermethylation and risk factors for HNC progression were analyzed (Table 1). QUADAS-2 evaluation analysis showed that all studies had relative elevated scores, indicating a comparatively high quality of the researchers included in this study. The median impact factor of these publications was 3.798 (range 0.652 to 9.238).

Table 1.

Hypermethylation in genes associated with risk factors in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in the 85 identified studies.

| Author | Impact factor | Type of Study | Population | Sample size | Anatomic location | Epigenetic alteration | Assay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cordeiro-Silva et al. | 1.698 | Case–Control | Brazil | 70/41 | OC | CDKN2A, SFN, EDNRB, RUNX3 | MSP |

| Sanchez-Cespedes et al. | 9.329 | Retrospective | USA | 95 | HNC | CDKN2A, MGMT, GSTP1, DAPK | MSP |

| Markowski et al. | 1.554 | Retrospective | Poland | 21 | larynx | HIC1 | qRT-PCR |

| Virani et al. | 3.362 | Retrospective | USA | 346 | HNC | CCNA1, NDN, CD1A, DCC, CDKN2A, GADD45A | MSP |

| Shintani et al. | 1.521 | Retrospective | Japan | 17 | OC | CDKN2A | MSP |

| Agnese et al. | 9.269 | Retrospective | Italy | 173 | HNC | CDKN2A | MSP |

| Kawakami et al. | 2.915 | Retrospective | Japan | 104 | OP | CDKN2A | MSP |

| Ruesga et al. | 5.992 | Prospective | Spain | 175 | OC | CDKN2A | MSP |

| Zheng et al. | 4.125 | Case–Control | USA | 208/ 245 | HNC | CDKN2A | qRT-PCR |

| Sun et al. | 3.234 | Prospective | USA | 197 | OC and OP | CDKN2A, CCNA1, DCC, TIMP3, MGMT, DAPK, MINT31 | MSP |

| Calmon et al. | 2.805 | Prospective | Brazil | 43 | HNC | CDKN2A, DAPK1, CDH1, ADAM23 | MSP |

| Langevin et al. | 5.108 | Case–Control | USA | 92/ 92 | HNC | FGDA, SERPINF1, WDR39, IL27, HYAL2, PLEKHA6 | qRT-PCR |

| Zhang et al. | 3.234 | Retrospective | Japan | 10 | OP | LCR | MSP |

| Hasegawa et al. | 5.979 | Retrospective | Israel | 80 | HNC | CDKN2A, DAPK, CDH1, RASSF1A | MSP |

| Misawa et al. | 3.081 | Retrospective | Japan | 100 | HNC | CDKN2A | MSP |

| Marsit et al. | 5.649 | Retrospective | USA | 340 | HNC | CDH1 | MSP |

| Dikshit et al. | 5.649 | Retrospective | Italy | 235 | HNC | MGMT, DAPK, CDKN2A, CDH1 | MSP |

| Farias et al. | 3.025 | Retrospective | Brazil | 75 | HNC | CDKN2A | MSP |

| Wong et al. | 5.417 | Prospective | China | 73 | HNC | P15, CDKN2A | MSP |

| Smith et al. | 5.531 | Retrospective | USA | 137 | HNC | CCNA1, MGMT, DCC, CDKN2A | MSP |

| Shaw et al. | 3.93 | Retrospective | UK | 48 | OC | CDKN2A, CYGB, CDH1, TMEFF2 | MSP |

| Wong et al. | 0.795 | Retrospective | Taiwan | 64 | OC | DAPK, MGMT | MSP |

| Dong et al. | 1.859 | Prospective | China | 30 | OC | CDKN2A | MSP |

| Prez-Sayans et al. | 1.553 | Retrospective | Spain | 68 | OC | CDKN2A | MSP |

| Tran et al. | 1.859 | Prospective | Vietnam | 36 | OC | CDKN2A, RASSF1A | MSP |

| Kaur et al. | 5.531 | Prospective | India | 92 | OC | DCC, EDNRB, CDKN2A, KIF1A | MSP |

| Virani et al. | 3.135 | Retrospective | USA | 98 | HNC | CCNA1, NDN | MSP |

| Nakagawa et al. | 3.523 | Prospective | Japan | 58 | OC | LRP1B | qRT-PCR |

| Morandi et al. | 1.252 | Retrospective | Italy | 48 | OC | GP1BB, ZAP70, KIF1A, CDKN2A, CDH1, miR137, miR375 | MSP |

| Taioli et al. | 3.362 | Retrospective | USA | 88 | OC and OP | MGMT, CDKN2A, RASSF1 | MSP |

| Parfenov et al. | 9.423 | Prospective | USA | 129 | HNC | BARX2, IRX4, SIM2 | qRT-PCR |

| Lee et al. | 7.429 | Retrospective | Taiwan | 40 | OC | BEX1, LDOC1 | MSP |

| Chang et al. | 5.649 | Prospective | China | 90 | HNC | P15 | MSP |

| Schussel et al. | 1.186 | Prospective | Brazil | 47 | OC | DACT1, DACT2 | MSP |

| Wilson et al. | 5.108 | Prospective | USA | 6 | HNC | CDH1 | MSP |

| Nayak et al. | 2.272 | Retrospective | USA | 124 | HNC | TIMP3, DAPK | MSP |

| Ogi et al. | 8.738 | Retrospective | Japan | 96 | OC | CDKN2A, P15, P14, DCC, DAPK, MINT1, MINT2, MINT27, MINT31 | qRT-PCR |

| Colacino et al. | 3.234 | Retrospective | USA | 68 | HNC | GRB7, CDH11, RUNX1T1, SYBL1, TUSC3, SPDEF, RASSF1, STAT5A, MGMT, ESR2, JAK3, HSD17B12 | MSP |

| Langevin et al. | 4.327 | Retrospective | USA | 154 | HNC | DKK1, ZCCHC14, MARCH4, ANKRD33B, SLC6A5, INPP5A, ATAD3C, PWWP2B, SAFB2, GABRA1, KCNQ1, PTHLH, ARHGEF2, CIT, SH3BP5 | qRT-PCR |

| Misawa et al. | 8.738 | Prospective | Japan | 100 | HNC | GALR1 | MSP |

| Langevin et al. | 3.607 | Retrospective | USA | 82 | OC | GABBR1 | qRT-PCR |

| Bebek et al. | 5.985 | Prospective | USA | 42 | HNC | MDR1, IL8, RARB, TGFBR2 | MSP |

| Ohta et al. | 1.262 | Prospective | Japan | 44 | OC | CDKN2A, P14ARF | MSP |

| Furniss et al. | 4.125 | Retrospective | USA | 303 | HNC | LRE1 | MSP |

| Zhao et al. | 2.301 | Retrospective | China | 41 | nasopharynx | GALC | qRT-PCR |

| Hsiung et al. | 4.125 | Case–Control | USA | 278/ 526 | OC and OP | MTHFR | MSP |

| Sinha et al. | 3.135 | Prospective | India | 38 | OC | CDKN2A | MSP |

| Khor et al. | 2.244 | Prospective | Malaysia | 20 | OC | CDKN2A, DDAH2, DUSP1 | MSP |

| O'Regan et al. | 2.769 | Prospective | Ireland | 24 | OC and OP | CDKN2A | MSP |

| Weiss et al. | 4.722 | Retrospective | Germany | 86 | HNC | TIMP3, CDH1, CDKN2A, DAPK1,TCF21, CD44, MLH1, MGMT, RASSF1, CCNA1, LARS2, CEBPA | MSP |

| Sun et al. | 8.738 | Retrospective | USA | 197 | HNC | CCNA1, MGMT, MINT31 | MSP |

| Supic et al. | 4.602 | Prospective | Serbia | 96 | OC | CDKN2A, RASSF1A, DAPK, CDH1, MGMT, hMLH1, WIF1, RUNX3 | MSP |

| Weiss et al. | 3.562 | Prospective | Germany | 74/ 41 | HNC | TCF21 | MSP |

| Ai et al. | 5.485 | Retrospective | USA | 100 | HNC | CDKN2A | MSP |

| El-Naggar et al. | 6.501 | Retrospective | USA | 46 | HNC | CDKN2A | MSP |

| González-Ramírez et al. | 3.607 | Case–Control | Mexico | 50/200 | OC | MLH1 | MSP |

| Gemenetzidis et al. | 3.234 | Prospective | UK | 75 | HNC | FOXM1 | qRT-PCR |

| Ishida et al. | 3.607 | Prospective | Japan | 49 | OC | CDKN2A, P14, RB1, P21, P27, PTEN, P73, MGMT, GSTP | MSP |

| Righini et al. | 8.738 | Prospective | France | 90 | HNC | TIMP3, CDH1, CDKN2A,MGMT, DAPK, RASSF1 | MSP |

| Subbalekha et al. | 3.607 | Case–Control | Thailand | 69/37 | OC | LINE1 | MSP |

| Dong et al. | 8.738 | Prospective | USA | 46 | OP | RASSF1A | MSP |

| Ovchinnikov et al. | 2.884 | Case–Control | Australia | 143/31 | HNC | RASSF1A, DAPK1, CDKN2A | MSP |

| Demokan et al. | 2.760 | Prospective | Turkey | 77 | HNC | CDKN2A | MSP |

| Kresty et al. | 9.329 | Retrospective | USA | 26 | OC | CDKN2A, P14 | MSP |

| Marsit et al. | 5.334 | Prospective | USA | 68 | HNC | HGF, FGF, ATP10A, NTRK3, ZAP70, GP1BB, SRC, EGF, EPHA2 | MSP |

| Mielcarek-Kuchta et al. | 2.926 | Prospective | Poland | 53 | OC and OP | CDKN2A, CDH1, ATM, FHIT, RAR | MSP |

| Steinmann et al. | 2.301 | Prospective | Germany | 54 | HNC | RASSF1A, CDKN2A, MGMT, DAPK, RARß, MLH1, CDH1, GSTP1, RASSF2, RASSF4, RASSF5, MST1, MST2, LATS1, LATS2 | MSP |

| Tan et al. | 5.569 | Prospective | France | 42 | HNC | CDKN2A, CCNA1, DCC | MSP |

| Pannone et al. | 1.718 | Prospective | Italy | 64 | OC and OP | CDKN2A | MSP |

| Kulkarni et al. | 3.607 | Prospective | India | 60 | OC | CDKN2A, DAPK, MGMT | MSP |

| Huang et al. | 2.207 | Case–Control | Taiwan | 31/40 | OC | SOX1, PAX1, ZNF582 | MSP |

| Misawa et al. | 1.736 | Prospective | Japan | 46 | HNC | COL1A2 | MSP |

| Koscielny et al. | 0.492 | Prospective | Germany | 67 | HNC | CDKN2A | MSP |

| Miracca et al. | 5.569 | Prospective | Brazil | 47 | HNC | CDKN2A | MSP |

| Rosas et al. | 9.329 | Retrospective | USA | 30 | HNC | CDKN2A, DAPK, MGMT | MSP |

| Roh et al. | 8.738 | Prospective | USA | 353 | HNC | CDKN2A, DCC, EDNRB, KIF1A | MSP |

| Supic et al. | 2.495 | Retrospective | Serbia | 76 | OC | RUNX3, W1F1 | MSP |

| Sharma et al. | 2.495 | Prospective | India | 73 | HNC | CYP1A1, CYP2A13, GSTM1 | MSP |

| Choudhury et al. | 3.234 | Retrospective | India | 116 | HNC | CDKN2A, DAPK, RASSF1, BRAC1, GSTP1, CDH1, MLH1, MINT1, MINT2, MINT31 | MSP |

| Park et al. | 4.444 | Prospective | USA | 22 | OP | LCR | MSP |

| Balderas-Loaeza et al. | 5.531 | Prospective | Mexico | 62 | OC | LCR | MSP |

| Marsit et al. | 5.531 | Retrospective | USA | 350 | HNC | SFRP1, SFRP2, SFRP4, SFRP5 | MSP |

| Ayadi et al. | 1.826 | Retrospective | Tunisia | 44 | nasopharynx | CDKN2A, DLEC1, BLU, CDH1 | MSP |

| Puri et al. | 0.933 | Retrospective | USA | 51 | HNC | MLH1, MGMT, CDKN2A | MSP |

| Gubanova et al. | 8.738 | Prospective | USA | 40 | OP | SMG1 | qRT-PCR |

MSP: methylation specific PCR; OC: oral cancer; OP: oropharyngeal cancer; HNC: head and neck cancer.

Of the 85 articles exploring DNA methylation and risk factors (including tobacco use, alcohol abuse, and HPV positivity) in HNC, 30 (35.3%) studies focused on North Americans populations followed by Japanese (n = 10; 11.8%), Brazilian (n = 5; 5.9%) and India population (n = 5; 5.9%). DNA methylation was widely analyzed by MSP of specific genes in 74 (87.1%) studies. The remaining researches used qRT-PCR as method (11 studies; 12.9%). The anatomic location in head and neck cancer was predominantly mixed (44 studies; 51.8%) followed by oral cavity (n = 27; 31.8%) and oral cavity mixed with oropharyngeal cases (n = 6; 7.1%). A total of 37 (46.5%) of the 85 articles only measured DNA methylation of a single gene (Table 1).

DNA methylation associated with cancer risk in HNC

Changes in DNA hypermethylation were identified for 120 genes (Table 1). These genes are enriched for biological processes related to cell proliferation and death, response to stimulus (including drugs), metabolism, and cellular motility and differentiation (Supplementary Table 2). Even though these genes came from different studies, the interactome analysis showed that some of these genes, such as CCNA1, SFN, ATM, GADD45A, CDKN2A, TP53, RB1 and RASSF1 are involved into common biological processes suggesting that they work together (Fig. 2). Thus, we verified the cellular pathways where the regulatory genes play critical role in the signaling networks, including p53, Wnt, MAPK and ErbB tyrosine kinase receptor signaling, as well as cytochrome P450-associated xenobiotic metabolism (Supplementary Table 3).

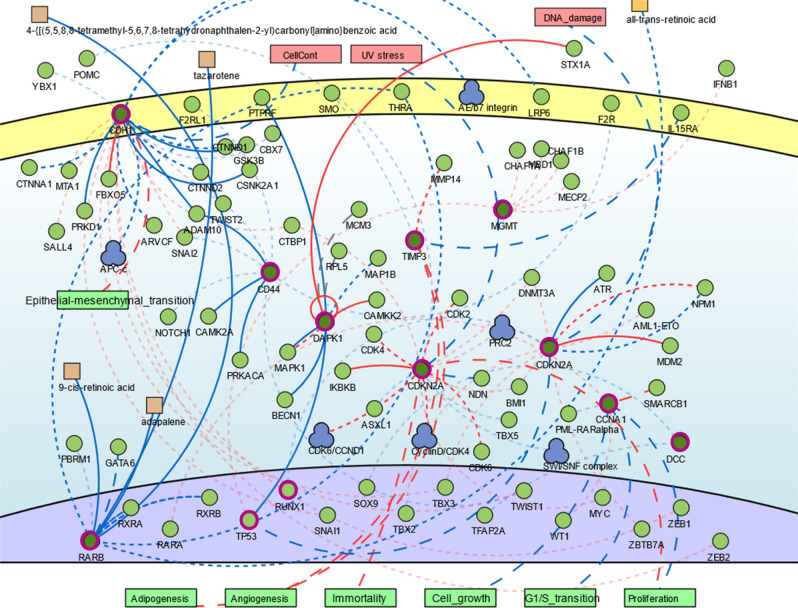

Figure 2.

Genomic network analysis showing the central role of genes related with cell cycle pathway. Genes hypermethylated (circled in pink) from different studies were involved into common biological processes suggesting that they work together. PPI analysis pointed to external stimulus, such as DNA damage, UV stress, all-trans-retinoic acid that could activate a cellular signalization to epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), adipogenesis, angiogenesis, immortality, cell growth, cell cycle and proliferation. Image done using the public repository SIGnaling Network Open Resource 2.0 (SIGNOR 2.0).

In the multivariate analysis, not all the 120 genes showed a significant correlation with alcohol, tobacco and/or HPV status. Rather, only the hypermethylation of TIMP3, DCC, DAPK1, CDH1, CCNA1, MGMT, P16 (CDKN2A), MINT, CD44, RARβ were associated with these known risk factors in progressive HNC. According to GSEA (Supplementary Table 2), five of these genes belong to four families sharing similar homology or biochemical activity: tumor suppressors (CDH1 and CDKN2A), protein kinase (DAPK1), cell differentiation markers (CDH1 and CD44) and transcriptional factor (RARβ). These ten genes were submitted to signaling network analysis revealing a protein-to-protein interaction (PPI) that pointed to external stimulus, such as DNA damage, UV stress, all-trans-retinoic acid that could activate a cellular signalization to epithelial-mesenchymal transition, adipogenesis, angiogenesis, immortality, cell growth, cell cycle (G1S transition) and proliferation (Fig. 2).

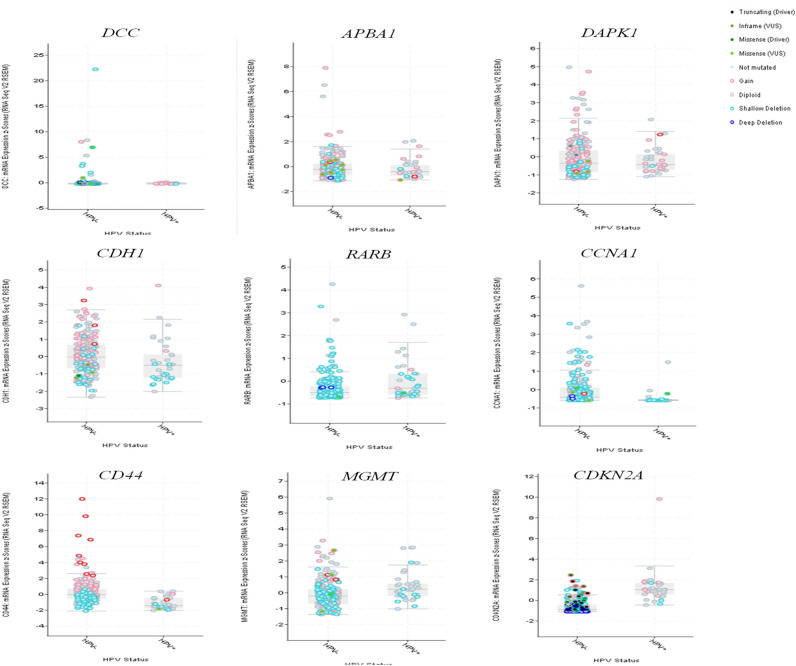

Finally, to confirm if these genes associated with risk factors (alcohol, tobacco and HPV) might have impact on patient’s survival probability, we validated them using an independent large cohort of 279 HNC patients with high-throughput information from Cancer Genome Atlas containing HM450 methylation and RNAseq data104. For these analyses, we used tools available in the cBioPortal105,106. Not all these genes were statistically associated with alcohol and tobacco in this cohort. However, regarding HPV status, CD44, CCNA1, DCC and TIMP3 were hypermethylated in the HNC HPV-negative (Fig. 3). The correlation between DNA hypermethylation and RNAseq data in this cohort confirms that DNA hypermethylation often leads to gene downregulation (Supplementary Fig. 1). There were no transcriptome data for DCC and CCNA1 in this study104. For the eight genes that had transcriptome data available in the dataset, except for APBA1, we validated the negative correlation between DNA methylation (HM450 methylation platform) and gene expression (using RNAseq data). CDH1 and CD44 gene expression were significantly expressed in the HPV-positive patients (Fig. 4A,B). The methylation status (or any other alteration) of these genes alone did not achieve statistical significance on their impact for the overall survival based on this dataset, which included a mixed of different anatomical location and heterogenous tumor stage and histological grade.

Figure 3.

Validation of the gene expression in a large cohort of 279 HNC cases from Cancer Genome Atlas containing HM450 methylation, RNAseq data as well as information regarding alcohol, tobacco, and HPV infection. CD44, CCNA1, DCC and TIMP3 were hypermethylated in the HNC HPV-negative cases. Image done using the open-access resource for interactive exploration of multidimensional cancer genomics data sets cBio Cancer Genomics Portal (http://cbioportal.org).

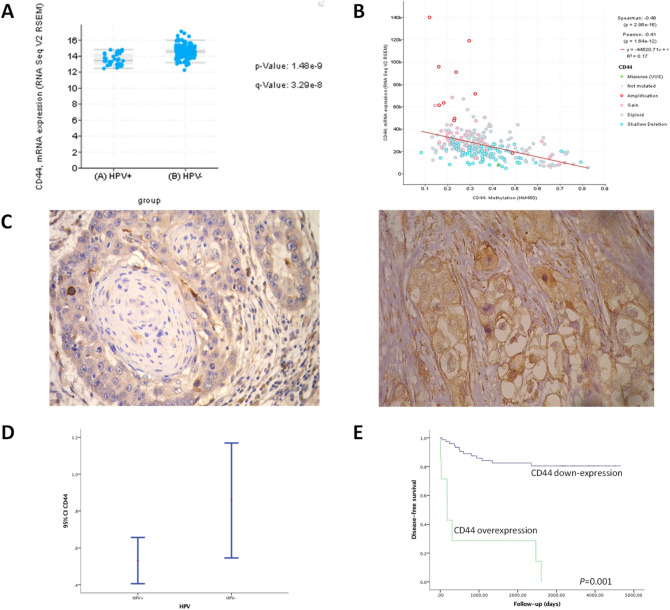

Figure 4.

(A) Transcription profile reveals CD44 is highly expressed in HPV-HNC. (B) Correlation between gene expression and epigenetic alteration. (C) Validation of the protein expression in an independent cohort of 100 HNC with long-term follow-up. Representative immunohistochemical staining for CD44 in head and neck cancer. The cytoplasmic membrane immunoreactivity for CD44 was clearly identified. Original magnification: 400×. (D) CD44 protein was differentially expressed HPV+ and HPV- HNC patients. Confidence intervals (CI 95%) show relative percentage and IHC intensity value. Y-axis represents numerical values corresponding to the percentage and intensity of expression. (E) Survival curves analysis according to the Kaplan–Meier method showing that patients with positive expression of CD44 had shorter survival rate in comparison with negative immunostaining (log-rank test, P < 0.01).

In order to analyze whether this alteration affected the translational level, we explored these two promising candidates (CD44 and CDH1) and their potential clinical impact by evaluating a cohort of 100 patients with unique tumor location at the tongue followed-up by 10 years (Fig. 4; Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Typically, HNC patients relapse within 2 years. Among our studied patients, 23 (23.0%) had recurrence, 28 (28.0%) had distant metastasis, and 50 (50.0%) died. Sixty-nine patients from 85 HNC cases presenting negative staining for CD44 protein expression, had statistically better disease-free survival probability compared with patients whose tumors overexpressed CD44 (log-rank test, P < 0.01) (Fig. 4C-E). The lower expression of CD44 might reflect the reduced number of cells with stem cell properties which explain the absence of metastasis and the better survival rates.

Prediction of the drugs to target the hypermethylated candidate genes

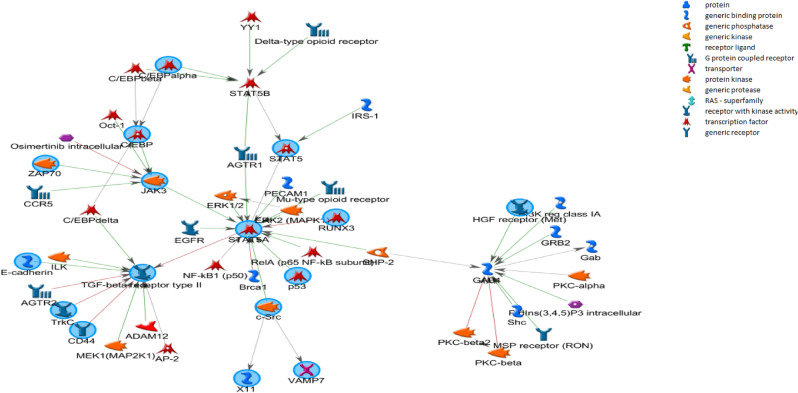

To elucidate the underlying mechanisms of the hypermethylated genes in relation to the HNC susceptibility, these 120 known genes were used as seed for network growth. We identified six core biological processes (FDR < 10–30 and Z-score > 90), which were enriched for cell cycle regulation and metabolic pathways. Finally, based on this criteria, 53 methylated genes showed strong correlation with cancer risk, then, we searched for drugs interfering with these networks. We found 71 drugs targeting 18 proteins in the six networks identified (Supplementary Table 4). Proteins targeted by the drugs include TGF-beta receptor type II (Lerdelimumab, Suramin, and Interferon beta), GAB1-RA (Primidone, Flumazenil, Oxazepam, Flurazepam, Methylphenobarbital, Clorazepate, Ganaxolone, Clomethiazole, Zaleplon, Ocinaplon, Methyprylon, Indiplon, Zolpidem, Pentobarbital and Secobarbital), JAK 3 (Tofacitinib) (Fig. 5), IL-6 (Dexamethasone, Aloperine), CCND1 (Silibinin) and SRC (Cediranib, Nintedanib, Dasatinib/BMS-354825 and Saracatinib). The complete list of potential drugs acting on proteins associated with gene hypermethylation in head and neck cancer and their functions are presented in Supplementary Table 4.

Figure 5.

Regulatory network of selected hypermethylated genes associated with risk factors in head and neck cancer. Genes regulated by methylation from independent published studies in head and neck cancer (such as GAB1, TGFB, and JAK3) belongs to similar networks known to play a fundamental role in cancer progression. These methylated genes are targeted by the drugs, including TGF-beta receptor type II (Lerdelimumab, Suramin, and Interferon beta), GAB1-RA (Primidone, Flumazenil, Oxazepam, Flurazepam, Methylphenobarbital, Clorazepate, Ganaxolone, Clomethiazole, Zaleplon, Ocinaplon, Methyprylon, Indiplon, Zolpidem, Pentobarbital and Secobarbital), JAK 3 (Tofacitinib). Graphs were extracted from Metacore, Thompson Reuters (https://portal.genego.com).

Discussion

In this systematic review we discussed and validated common genes regulated by DNA hypermethylation with fundamental role in HNC progression and metastatic competence, considering independent investigations with different HNC cohorts around the world. The clinical impact of these genes as prognostic factor is highly relevant to open-up new avenues to the therapeutic approach towards a personalized medicine. Although numerous advances in diagnosis and treatment have been achieved in the last years, 66% of HNC are still diagnosed at advanced stages (III or IV)107, 20% of the patients will develop an upper aerodigestive tract secondary tumor2,19,109 and more than 50% will died during the 5 years of follow-up due to the metastatic tumors.

The accumulation of epigenetic and genetic modifications, frequently associated with exposure to carcinogens, confer advantages to the cell in cancer division and survival, such as growth factor-independent proliferation, resistance to apoptosis, and an enhanced motility capability to migrate through the extracellular matrix (ECM) and invade adjacent tissues110. DNA methylation events is a critical tumor-specific event occurring early in tumor progression to metastasis and it can be easily detected by PCR in a manner that is minimally invasive to the patient109. Our review identified DNA methylation in 120 genes associated with high risk for developing HNC. The expression patterns of these hypermethylated genes were correlated with the risk factors and their impact for patient’s survival probability, indicating they can act as predictors in progressive HNC.

The multivariate analysis showed that numerous suppressor genes were significantly hypermethylated such as P16, TIMP3, DCC, DAPK, MINT31, RARβ, MGMT, CCNA1, CD44, and CDH1; these genes are involved in cell–cell adhesion, cell polarity and tissue morphogenesis. This gene was analyzed alone or in gene panels, however, the studies showed discordant results. In one report, P16 hypermethylation was associated with carcinogenesis of oral epithelial dysplasia and it was considered a potential biomarker for the prediction of tumor progression of mild or moderate oral dysplasia64,83. The hypermethylation of the P16 promoter gene has also been described in advanced oral cancer associated with increased risk of loco-regional recurrences66. Different degrees of P16 hypermethylation have been reported in oral cancer23,26,46,62,74,75,91,94 and in others HNC location73,93.

Interestingly, promoter hypermethylation profile of the P16, MGMT, GSTP1 and DAPK can be used as molecular biomarkers to detect recurrent tumors using liquid biopsy111. Since gene hypermethylation has been found to be a common and early event in several types of cancer, including HNC, it has emerged as a promising target for non-invasive detection strategies for tumor recurrence and metastasis. It was known that cancer cells shed their DNA into the bloodstream and that circulating free DNA (cfDNA) share molecular similarities with the primary tumor, including DNA hypermethylation. So, it has been suggested that tumor specific DNA hypermethylation in serum is useful for diagnosis and prediction prognosis112. This information is yet to be translated into useful and reliable tools for HNC in the clinical practice. Nonetheless, due to the increase of the sensitivity and the high-throughput quantitative methodologies for hypermethylation analysis, specific candidates will surely emerge by combination of different genetic and epigenetic panels to achieve accuracy in the neoplastic detection113. Over the next years, clinical trials on diagnostic and treatment approaches based on hypermethylation markers will be available for the assessment of HNC prognosis, therapeutic strategies and to predict the response to the treatment.

Researchers found significant differences in the tumorigenesis and HNC prognosis of patients with HPV-related cancer versus HPV-negative tumors and have tended to classify HPV associated malignancies as a distinct biologic entity. HPV-negative HNC is related to oral sexual behaviour, which is associated with HPV transmission114,115. Relative to HPV-negative malignancies, HPV-positive cancers are associated with a more favourable prognosis114–116. However, most patients (> 75%) with HPV-unassociated HNCs present tumors with poorer clinical outcome, do not respond to standard treatments due to a higher rate of relapses115,116. The majority of the studies included in our analysis, including HPV-positive patients, have strong association with alcohol and tobacco consumption. Previous studies suggested that although HPV-positive cancers in heavy smokers may be initiated through virus-related mutations, they go on to acquire tobacco-related mutations and become less dependent on the E6/E7 carcinogenesis mechanisms typically associated with the virus117. If epigenetic alteration can be modified by alcohol and tobacco status in HPV-positive patients, the gene silencing by hypermethylation can also be influenced by the combination of different risk factors, interfering not only in the tumor initiation process but also in the HNC progression to metastasis. A current limitation in the prognosis and therapeutic strategies of HNC is the lack of consistent methods and the use of large cohort studies to adequately address the influence of the etiologic complexity and the tumor heterogeneity (anatomical and histological) in the metastatic competence of this disease.

In this study, we firstly performed a systematic review to disclose potential candidates associated with HNC susceptibility that was confirmed by a validation in public platform from the TCGA datasets with 279 HNC cases. However, we also conducted an additional validation of the most relevant hypermethylated genes that showed statistical significance in both previous analysis by using an independent cohort with single tumor anatomical location (only tongue cancer) considering alcohol consumption, tobacco use and HPV status. After this screening, only CD44 expression showed significant clinical impact at the translational level being associated with tumor recurrence. CD44 is a well-characterized cell surface glycoprotein receptor associated with a subpopulation of resilient tumor cells with enhanced carcinogenic properties specially involved with increased cell migration. We confirmed the increased proportions of CD44 + cells correlated with poor patient’s outcome in HPV negative HNC patients. The lower expression of CD44 might reflect the reduced number of cells with stem cell properties which explain the absence of metastasis and the better survival rates. In HNC, CD44 + expression has been associated with tumor-initiating cells or cancer stem cells due to their ability to persist and self-renew following therapy. Extensive investigations in our field have been performed with a hope to find a new prognostic tool to understand the basis of molecular carcinogenesis in HNC but also to identify potential therapeutic opportunities toward personalized medicine to manage patients with advanced disease. The ability to manipulate DNA methylation status and gene function by local and systemic delivery of epigenetic drugs (methylation inhibitors [e.g., 5-azacytidine]; antisense oligonucleotides [e.g., MG98]; and small molecule DNA methylation inhibitor [RG108]) has recently gained interest as novel therapeutic approach. Here, we reported potential drugs to target the most common alteration proposed in literature related to DNA hypermethylation in progressive HNC. The list of drugs available (Supplementary Table 4) may be used to block multiple nodes in critical pathways involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, tumor growth and survival in HNC at high-risk for recurrence.

In summary, this review highlights the impact of DNA hypermethylation associated with the main risk factors for HNC and show, from independent studies, the implication of methylated genes in the regulation of critical network with fundamental role in cancer progression to metastasis, which could be used as a potential therapeutic target and long-term surveillance for patients with invasive HNC.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NCOHR, Global Affair/DFATD#249584, Brazil-Canada#249569, and RSBO#80596.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: M.A.J., M.M., and S.D.S. Acquisition of data: J.H., O.V., A.B. Analysis and interpretation of data: I.I., M.H., A.M., M.A.J., M.M., S.D.S. Drafting of the manuscript: M.A.J., M.M., S.D.S. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: J.H., O.V., A.B., I.I., M.M., M.J., A.M., M.A.J., SDS. Study supervision: S.D.S. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-89476-x.

References

- 1.Cancer Research, https://www.cancerresearchuk.org. Accessed May 2020.

- 2.Silva SD, Hier M, Mlyarek A, Kowalski LP, Alaoui-Jamali M. Recurrent oral cancer: Current and emerging therapeutic approaches. Front. Pharmacol. 2012;3:149. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canning M, Guo G, Yu M, Myint C, Groves MW, Byrd JK, Cui Y. Heterogeneity of the head and neck squamous cell carcinoma immune landscape and its impact on immunotherapy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019;7:52. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2019.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis A, Kang R, Levine A, Maghami E. The new face of head and neck cancer: The HPV epidemic. Oncology. 2015;29:616–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hashibe M, Brennan P, Chuang SC, Chuang SC, Boccia S, Castellsague X, Chen C, Curado MP, Dal Maso L, Daudt AW, Fabianova E, Fernandez L, Wünsch-Filho V, Franceschi S, Hayes RB, Herrero R, Kelsey K, Koifman S, La Vecchia C, Lazarus P, Levi F, Lence JJ, Mates D, Matos E, Menezes A, McClean MD, Muscat J, Eluf-Neto J, Olshan AF, Purdue M, Rudnai P, Schwartz SM, Smith E, Sturgis EM, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, Talamini R, Wei Q, Winn DM, Shangina O, Pilarska A, Zhang ZF, Ferro G, Berthiller J, Boffetta P. Interaction between tobacco and alcohol use and the risk of head and neck cancer: Pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2009;18:541–550. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laprise C, Madathil SA, Allison P, Abraham P, Raghavendran A, Shahul HP, ThekkePurakkal AS, Castonguay G, Coutlée F, Schlecht NF, Rousseau MC, Franco EL, Nicolau B. No role for human papillomavirus infection in oral cancers in a region in southern India. Int. J. Cancer. 2016;138:912–917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stadler ME, Patel MR, Couch ME, Hayes DN. Molecular biology of head and neck cancer: Risks and pathways. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2008;22(6):1099–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russo D, Merolla F, Varricchio S, et al. Epigenetics of oral and oropharyngeal cancers cancers [published correction appears in Biomed Rep. 2020 May;12(5):290] Biomed. Rep. 2018;9(4):275–283. doi: 10.3892/br.2018.1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma S, Kelly TK, Jones PA. Epigenetics in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31(1):27–36. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002;3(6):415–28. doi: 10.1038/nrg816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Momparler RL, Bovenzi V. DNA methylation and cancer. J. Cell Physiol. 2000;183(2):145–154. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200005)183:2<145::AID-JCP1>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dikshit RP, Gillio-Tos A, Brennan P, De Marco L, Fiano V, Martinez-Peñuela JM, Boffetta P, Merletti F. Hypermethylation, risk factors, clinical characteristics, and survival in 235 patients with laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancers. Cancer. 2007;110(8):1745–51. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azarschab P, Stembalska A, Loncar MB, Pfister M, Sasiadek MM, Blin N. Epigenetic control of E-cadherin (CDH1) by CpG methylation in metastasising laryngeal cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2003;10(2):501–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett KL, Lee W, Lamarre E, Zhang X, Seth R, Scharpf J, Hunt J, Eng C. HPV status-independent association of alcohol and tobacco exposure or prior radiation therapy with promoter methylation of FUSSEL18, EBF3, IRX1, and SEPT9, but not SLC5A8, in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Genes Chromosom. Cancer. 2010;49(4):319–326. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ayadi W, Karray-Hakim H, Khabir A, Feki L, Charfi S, Boudawara T, Ghorbel A, Daoud J, Frikha M, Busson P, Hammami A. Aberrant methylation of p16, DLEC1, BLU and E-cadherin gene promoters in nasopharyngeal carcinoma biopsies from Tunisian patients. Anticancer Res. 2008;8(4B):2161–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102(43):15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson KF, et al. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2003;34(3):267–273. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Licata L, Lo Surdo P, Iannuccelli M, et al. SIGNOR 2.0, the SIGnaling network open resource 2.0: 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;48(D1):D504–D510. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.da Silva SD, Marchi FA, Su J, Yang L, Valverde L, Hier J, Bijian K, Hier M, Mlynarek A, Kowalski LP, Alaoui-Jamali MA. Co-overexpression of TWIST1-CSF1 is a common event in metastatic oral cancer and drives biologically aggressive phenotype. Cancers. 2021;13:153. doi: 10.3390/cancers13010153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Freitas C-S, Oliveira ZF, de Podestá JR, Gouvea SA, Von Zeidler SV, Louro ID. Methylation analysis of cancer-related genes in non-neoplastic cells from patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2011;38(8):5435–5441. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-0698-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanchez-Cespedes M, Esteller M, Wu L, et al. Gene promoter hypermethylation in tumors and serum of head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2000;60(4):892–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Markowski J, Sieroń AL, Kasperczyk K, Ciupińska-Kajor M, Auguściak-Duma A, Likus W. Expression of the tumor suppressor gene hypermethylated in cancer 1 in laryngeal carcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2015;9(5):2299–2302. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Virani S, Bellile E, Bradford CR, et al. NDN and CD1A are novel prognostic methylation markers in patients with head and neck squamous carcinomas. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:825. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1806-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakahara Y, Shintani S, Mihara M, Hino S, Hamakawa H. Detection of p16 promoter methylation in the serum of oral cancer patients. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2006;35(4):362–365. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agnese V, Corsale S, Calò V, et al. Significance of P16INK4A hypermethylation gene in primary head/neck and colorectal tumors: It is a specific tissue event? Results of a 3-year GOIM (Gruppo Oncologico dell'Italia Meridionale) prospective study. Ann. Oncol. 2006;17(Suppl 7):vii137–vii141. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawakami H, Okamoto I, Terao K, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA and p16 expression in Japanese patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2013;2(6):933–941. doi: 10.1002/cam4.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruesga MT, Acha-Sagredo A, Rodríguez MJ, et al. p16(INK4a) promoter hypermethylation in oral scrapings of oral squamous cell carcinoma risk patients. Cancer Lett. 2007;250(1):140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng Y, Shen H, Sturgis EM, et al. Haplotypes of two variants in p16 (CDKN2/MTS-1/INK4a) exon 3 and risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: A case-control study [published correction appears in Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2002 Nov; 11(11):1511] Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2002;11(7):640–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun YW, Chen KM, Imamura Kawasawa Y, et al. Hypomethylated Fgf3 is a potential biomarker for early detection of oral cancer in mice treated with the tobacco carcinogen dibenzo[def, p]chrysene. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(10):e0186873. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calmon MF, Colombo J, Carvalho F, et al. Methylation profile of genes CDKN2A (p14 and p16), DAPK1, CDH1, and ADAM23 in head and neck cancer. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2007;173(1):31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langevin SM, Koestler DC, Christensen BC, et al. Peripheral blood DNA methylation profiles are indicative of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: An epigenome-wide association study. Epigenetics. 2012;7(3):291–299. doi: 10.4161/epi.7.3.19134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang C, Deng Z, Pan X, Uehara T, Suzuki M, Xie M. Effects of methylation status of CpG sites within the HPV16 long control region on HPV16-positive head and neck cancer cells. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0141245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hasegawa M, Nelson HH, Peters E, Ringstrom E, Posner M, Kelsey KT. Patterns of gene promoter methylation in squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Oncogene. 2002;21(27):4231–4236. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Misawa K, Kanazawa T, Misawa Y, et al. Frequent promoter hypermethylation of tachykinin-1 and tachykinin receptor type 1 is a potential biomarker for head and neck cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2013;139(5):879–889. doi: 10.1007/s00432-013-1393-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marsit CJ, McClean MD, Furniss CS, Kelsey KT. Epigenetic inactivation of the SFRP genes is associated with drinking, smoking and HPV in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer. 2006;119(8):1761–1766. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dikshit RP, Gillio-Tos A, Brennan P, et al. Hypermethylation, risk factors, clinical characteristics, and survival in 235 patients with laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancers. Cancer. 2007;110(8):1745–1751. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farias LC, Fraga CA, De Oliveira MV, et al. Effect of age on the association between p16CDKN2A methylation and DNMT3B polymorphism in head and neck carcinoma and patient survival. Int. J. Oncol. 2010;37(1):167–176. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong TS, Man MW, Lam AK, Wei WI, Kwong YL, Yuen AP. The study of p16 and p15 gene methylation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and their quantitative evaluation in plasma by real-time PCR. Eur. J. Cancer. 2003;39(13):1881–1887. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(03)00428-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith IM, Mydlarz WK, Mithani SK, Califano JA. DNA global hypomethylation in squamous cell head and neck cancer associated with smoking, alcohol consumption and stage. Int. J. Cancer. 2007;121(8):1724–1728. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaw R, Christensen A, Java K, et al. Intraoperative sentinel lymph node evaluation: Implications of cytokeratin 19 expression for the adoption of OSNA in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2016;23(12):4042–4048. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5337-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong TS, Man MW, Lam AK, Wei WI, Kwong YL, Yuen AP. The study of p16 and p15 gene methylation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and their quantitative evaluation in plasma by real-time PCR. Eur. J. Cancer. 2003;39(13):1881–1887. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(03)00428-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dong SM, Kim HS, Rha SH, Sidransky D. Promoter hypermethylation of multiple genes in carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Clin. Cancer Res. 2001;7(7):1982–1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pérez-Sayáns M, Suárez-Peñaranda JM, Padín-Iruegas ME, et al. The loss of p16 expression worsens the prognosis of OSCC. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2015;23(10):724–732. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tran TN, Liu Y, Takagi M, Yamaguchi A, Fujii H. Frequent promoter hypermethylation of RASSF1A and p16INK4a and infrequent allelic loss other than 9p21 in betel-associated oral carcinoma in a Vietnamese non-smoking/non-drinking female population. J. Oral. Pathol. Med. 2005;34(3):150–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2004.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaur J, Demokan S, Tripathi SC, et al. Promoter hypermethylation in Indian primary oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer. 2010;127(10):2367–2373. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Virani S, Light E, Peterson LA, et al. Stability of methylation markers in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2016;38(Suppl 1):E1325–E1331. doi: 10.1002/hed.24223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakagawa T, Matsusaka K, Misawa K, et al. Frequent promoter hypermethylation associated with human papillomavirus infection in pharyngeal cancer. Cancer Lett. 2017;407:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morandi L, Gissi D, Tarsitano A, et al. DNA methylation analysis by bisulfite next-generation sequencing for early detection of oral squamous cell carcinoma and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion from oral brushing. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2015;43(8):1494–1500. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2015.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Oliveira SR, Da Silva IC, Mariz BA, Pereira AM, De Oliveira NF. DNA methylation analysis of cancer-related genes in oral epithelial cells of healthy smokers. Arch. Oral. Biol. 2015;60(6):825–833. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2015.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taioli E, Ragin C, Wang XH, et al. Recurrence in oral and pharyngeal cancer is associated with quantitative MGMT promoter methylation. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:354. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parfenov M, Pedamallu CS, Gehlenborg N, et al. Characterization of HPV and host genome interactions in primary head and neck cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci U. S. A. 2014;111(43):15544–15549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416074111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee CH, Wong TS, Chan JY, Lu SC, Lin P, Cheng AJ, Chen YJ, Chang JS, Hsiao SH, Leu YW, Li CI, Hsiao JR, Chang JY. Epigenetic regulation of the X-linked tumour suppressors BEX1 and LDOC1 in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Pathol. 2013;230(3):298–309. doi: 10.1002/path.4173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chang HW, Ling GS, Wei WI, Yuen AP. Smoking and drinking can induce p15 methylation in the upper aerodigestive tract of healthy individuals and patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;101(1):125–132. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schussel JL, Kalinke LP, Sassi LM, et al. Expression and epigenetic regulation of DACT1 and DACT2 in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Biomark. 2015;15(1):11–17. doi: 10.3233/CBM-140436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilson GA, Lechner M, Köferle A, et al. Integrated virus-host methylome analysis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Epigenetics. 2013;8(9):953–961. doi: 10.4161/epi.25614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nayak CS, Carvalho AL, Jeronimo C, et al. Positive correlation of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-3 and death-associated protein kinase hypermethylation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(8):1376–1380. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31806865a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ogi K, Toyota M, Ohe-Toyota M, et al. Aberrant methylation of multiple genes and clinicopathological features in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2002;8(10):3164–3171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Colacino JA, Dolinoy DC, Duffy SA, et al. Comprehensive analysis of DNA methylation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma indicates differences by survival and clinicopathologic characteristics. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e54742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Langevin SM, Eliot M, Butler RA, et al. CpG island methylation profile in non-invasive oral rinse samples is predictive of oral and pharyngeal carcinoma. Clin. Epigenet. 2015;7:125. doi: 10.1186/s13148-015-0160-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Misawa K, Kanazawa T, Misawa Y, Imai A, Endo S, Hakamada K, Mineta H. Hypermethylation of collagen α2 (I) gene (COL1A2) is an independent predictor of survival in head and neck cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2011–2012;10(3–4):135–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Langevin SM, Butler RA, Eliot M, et al. Novel DNA methylation targets in oral rinse samples predict survival of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral. Oncol. 2014;50(11):1072–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bebek G, Bennett KL, Funchain P, et al. Microbiomic subprofiles and MDR1 promoter methylation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21(7):1557–1565. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ohta S, Uemura H, Matsui Y, et al. Alterations of p16 and p14ARF genes and their 9p21 locus in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. Endod. 2009;107(1):81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Furniss CS, Marsit CJ, Houseman EA, Eddy K, Kelsey KT. Line region hypomethylation is associated with lifestyle and differs by human papillomavirus status in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2008;17(4):966–971. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cao YM, Gu J, Zhang YS, et al. Aberrant hypermethylation of the HOXD10 gene in papillary thyroid cancer with BRAFV600E mutation. Oncol. Rep. 2018;39(1):338–348. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.6058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hsiung DT, Marsit CJ, Houseman EA, et al. Global DNA methylation level in whole blood as a biomarker in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2007;16(1):108–114. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sinha P, Bahadur S, Thakar A, et al. Significance of promoter hypermethylation of p16 gene for margin assessment in carcinoma tongue. Head Neck. 2009;31(11):1423–1430. doi: 10.1002/hed.21122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Khor GH, Froemming GR, Zain RB, et al. DNA methylation profiling revealed promoter hypermethylation-induced silencing of p16, DDAH2 and DUSP1 in primary oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2013;10(12):1727–1739. doi: 10.7150/ijms.6884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.O'Regan EM, Toner ME, Finn SP, et al. p16(INK4A) genetic and epigenetic profiles differ in relation to age and site in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Hum. Pathol. 2008;39(3):452–458. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weiss D, Basel T, Sachse F, Braeuninger A, Rudack C. Promoter methylation of cyclin A1 is associated with human papillomavirus 16 induced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma independently of p53 mutation. Mol. Carcinog. 2011;50(9):680–688. doi: 10.1002/mc.20798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sun W, Zaboli D, Wang H, et al. Detection of TIMP3 promoter hypermethylation in salivary rinse as an independent predictor of local recurrence-free survival in head and neck cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18(4):1082–1091. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Supic G, Kozomara R, Jovic N, Zeljic K, Magic Z. Hypermethylation of RUNX3 but not WIF1 gene and its association with stage and nodal status of tongue cancers. Oral Dis. 2011;17(8):794–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Weiss D, Stockmann C, Schrödter K, Rudack C. Protein expression and promoter methylation of the candidate biomarker TCF21 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Oncol. (Dordr). 2013;36(3):213–224. doi: 10.1007/s13402-013-0129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ai L, Stephenson KK, Ling W, et al. The p16 (CDKN2a/INK4a) tumor-suppressor gene in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: A promoter methylation and protein expression study in 100 cases. Mod. Pathol. 2003;16(9):944–950. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000085760.74313.DD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.El-Naggar AK, Lai S, Clayman G, et al. Methylation, a major mechanism of p16/CDKN2 gene inactivation in head and neck squamous carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 1997;151(6):1767–1774. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.González-Ramírez I, Ramírez-Amador V, Irigoyen-Camacho ME, et al. hMLH1 promoter methylation is an early event in oral cancer. Oral. Oncol. 2011;47(1):22–26. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gemenetzidis E, Bose A, Riaz AM, et al. FOXM1 upregulation is an early event in human squamous cell carcinoma and it is enhanced by nicotine during malignant transformation. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(3):e4849. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ishida E, Nakamura M, Ikuta M, et al. Promotor hypermethylation of p14ARF is a key alteration for progression of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral. Oncol. 2005;41(6):614–622. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Righini CA, de Fraipont F, Timsit JF, et al. Tumor-specific methylation in saliva: A promising biomarker for early detection of head and neck cancer recurrence. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007;13(4):1179–1185. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Subbalekha K, Pimkhaokham A, Pavasant P, et al. Detection of LINE-1s hypomethylation in oral rinses of oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. Oral. Oncol. 2009;45(2):184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dong SM, Sun DI, Benoit NE, Kuzmin I, Lerman MI, Sidransky D. Epigenetic inactivation of RASSF1A in head and neck cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003;9(10 Pt 1):3635–3640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ovchinnikov DA, Cooper MA, Pandit P, et al. Tumor-suppressor gene promoter hypermethylation in saliva of head and neck cancer patients. Transl. Oncol. 2012;5(5):321–326. doi: 10.1593/tlo.12232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Demokan S, Chuang A, Suoğlu Y, et al. Promoter methylation and loss of p16(INK4a) gene expression in head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2012;34(10):1470–1475. doi: 10.1002/hed.21949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kresty LA, Mallery SR, Knobloch TJ, et al. Alterations of p16(INK4a) and p14(ARF) in patients with severe oral epithelial dysplasia. Cancer Res. 2002;62(18):5295–5300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chen AA, Marsit CJ, Christensen BC, et al. Genetic variation in the vitamin C transporter, SLC23A2, modifies the risk of HPV16-associated head and neck cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(6):977–981. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Marsit CJ, Christensen BC, Houseman EA, et al. Epigenetic profiling reveals etiologically distinct patterns of DNA methylation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(3):416–422. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mielcarek-Kuchta D, Paluszczak J, Seget M, et al. Prognostic factors in oral and oropharyngeal cancer based on ultrastructural analysis and DNA methylation of the tumor and surgical margin. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(8):7441–7449. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1958-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Steinmann K, Sandner A, Schagdarsurengin U, Dammann RH. Frequent promoter hypermethylation of tumor-related genes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2009;22(6):1519–1526. doi: 10.3892/or_00000596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tan HK, Saulnier P, Auperin A, et al. Quantitative methylation analyses of resection margins predict local recurrences and disease-specific deaths in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Br. J Cancer. 2008;99(2):357–363. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pannone G, Rodolico V, Santoro A, et al. Evaluation of a combined triple method to detect causative HPV in oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas: p16 immunohistochemistry, consensus PCR HPV-DNA, and in situ hybridization. Infect. Agent Cancer. 2012;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kulkarni V, Saranath D. Concurrent hypermethylation of multiple regulatory genes in chewing tobacco associated oral squamous cell carcinomas and adjacent normal tissues. Oral. Oncol. 2004;40(2):145–153. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(03)00143-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Huang C, Zhang P, Zhang D, Weng X. The prognostic implication of slug in all tumour patients—a systematic meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2016;46(5):398–407. doi: 10.1111/eci.12608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kanazawa T, Misawa K, Misawa Y, et al. G-protein-coupled receptors: Next generation therapeutic targets in head and neck cancer? Toxins (Basel). 2015;7(8):2959–2984. doi: 10.3390/toxins7082959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Koscielny S, Dahse R, Ernst G, von Eggeling F. The prognostic relevance of p16 inactivation in head and neck cancer. ORL J. Otorhinolaryngol. Relat. Spec. 2007;69(1):30–36. doi: 10.1159/000096714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Miracca EC, Kowalski LP, Nagai MA. High prevalence of p16 genetic alterations in head and neck tumours. Br J Cancer. 1999;81(4):677–683. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rosas SL, Koch W, da Costa Carvalho MG, et al. Promoter hypermethylation patterns of p16, O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase, and death-associated protein kinase in tumors and saliva of head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2001;61(3):939–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Roh JL, Wang XV, Manola J, Sidransky D, Forastiere AA, Koch WM. Clinical correlates of promoter hypermethylation of four target genes in head and neck cancer: A cooperative group correlative study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;19(9):2528–2540. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sharma R, Panda NK, Khullar M. Hypermethylation of carcinogen metabolism genes, CYP1A1, CYP2A13 and GSTM1 genes in head and neck cancer. Oral Dis. 2010;16(7):668–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2010.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Choudhury JH, Ghosh SK. Promoter hypermethylation profiling identifies subtypes of head and neck cancer with distinct viral, environmental, genetic and survival characteristics. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0129808. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Park IS, Chang X, Loyo M, et al. Characterization of the methylation patterns in human papillomavirus type 16 viral DNA in head and neck cancers. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila) 2011;4(2):207–217. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Balderas-Loaeza A, Anaya-Saavedra G, Ramirez-Amador VA, et al. Human papillomavirus-16 DNA methylation patterns support a causal association of the virus with oral squamous cell carcinomas. Int. J. Cancer. 2007;120(10):2165–2169. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ayadi W, Karray-Hakim H, Khabir A, et al. Aberrant methylation of p16, DLEC1, BLU and E-cadherin gene promoters in nasopharyngeal carcinoma biopsies from Tunisian patients. Anticancer Res. 2008;28(4B):2161–2167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Puri SK, Si L, Fan CY, Hanna E. Aberrant promoter hypermethylation of multiple genes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2005;26(1):12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gubanova E, Issaeva N, Gokturk C, Djureinovic T, Helleday T. SMG-1 suppresses CDK2 and tumor growth by regulating both the p53 and Cdc25A signaling pathways. Cell Cycle. 2013;12(24):3770–3780. doi: 10.4161/cc.26660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Network CGA. Comprehensive genomic characterization of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Nature. 2015;517(7536):576–582. doi: 10.1038/nature14129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, Antipin Y, Reva B, Goldberg AP, Sander C, Schultz N. The cBio cancer genomics portal: An open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(5):401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, et al. 2013 Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci. Signal. 2013;6(269):11. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kowalski LP, Carvalho AL, Martins Priante AV, Magrin J. Predictive factors for distant metastasis from oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral. Oncol. 2005;41:534–541. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Stephen JK, Chen KM, Havard S, Harris G, Worsham MJ. Promoter methylation in head and neck tumor genesis. Methods Mol. Biol. (Clifton, NJ) 2012;863:187–206. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-612-8_11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Martin TA, Ye L, Sanders AJ, et al. Cancer invasion and metastasis: Molecular and cellular perspective. In Madame Curie Bioscience Database [Internet] (Landes Bioscience, Austin, TX, 2000–2013).

- 111.Sanchez-Cespedes M, Esteller M, Wu L, Nawroz-Danish H, Yoo GH, Koch WM, Jen J, Herman JG, Sidransky D. Gene promoter hypermethylation in tumors and serum of head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2000;60:892–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Avraham A, Uhlmann R, Shperber A, et al. Serum DNA methylation for monitoring response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Int. J. Cancer. 2012;131(7):E1166–E1172. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Demokan S, Dalay N. Role of DNA methylation in head and neck cancer. Clin. Epigenet. 2011;2(2):123–150. doi: 10.1007/s13148-011-0045-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29(32):4294–4301. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gillison ML, Broutian T, Pickard RK, et al. Prevalence of oral HPV infection in the United States, 2009–2010. JAMA. 2012;307(7):693–703. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363(1):24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Howard JD, Chung CH. Biology of human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal cancer. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2012;22(3):187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.