Abstract

Background

Postprandial hypoglycemia after bariatric surgery is an exigent disorder, often impacting the quality of life. Distinguishing clinically relevant hypoglycemic episodes from symptoms of other origin can be challenging. Diagnosis is demanding and often requires an extensive testing such as prolonged glucose tolerance or mixed-meal test. Therefore, we investigated whether baseline parameters of patients after gastric bypass with suspected hypoglycemia can predict the diagnosis.

Methods

We analyzed data from 35 patients after gastric bypass with suspected postprandial hypoglycemia and performed a standardized mixed-meal test. Hypoglycemia was defined by the appearance of typical symptoms, low plasma glucose, and relief of symptoms following glucose administration. Parameters that differed in patients with and without hypoglycemia during MMT were identified and evaluated for predictive precision using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) areas under the curve (AUC).

Results

Out of 35 patients, 19 (54%) developed symptomatic hypoglycemia as a result of exaggerated insulin and C-peptide release in response to the mixed-meal. Hypoglycemic patients exhibited lower glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and higher absolute and relative weight loss from pre-surgery to study date. HbA1c and absolute weight loss alone could achieve acceptable AUCs in ROC analyses (0.76 and 0.72, respectively) but a combined score of absolute weight loss divided by HbA1c (0.78) achieved the best AUC.

Conclusions

HbA1c and weight loss differed in patients with and without symptomatic hypoglycemia during mixed-meal test. These baseline parameters could be used for screening of postprandial hypoglycemia in patients after gastric bypass and may facilitate the selection of patients requiring further evaluation.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11695-021-05277-1.

Keywords: Postprandial hypoglycemia, Late-dumping, Bariatric surgery, Mixed-meal test, Complications

Introduction

Bariatric surgery is an effective treatment modality for obesity [1–3] with confirmed long-term safety and overall benefit regarding weight loss, components of the metabolic syndrome, quality of life, and survival [4–6].

Nevertheless, up to a third of postbariatric patients report symptoms of postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia [7], whereas some studies report even higher prevalence rates in standardized test settings [8, 9] and severe hypoglycemic episodes occurring in less than 12% of patients [10, 11]. However, the exact prevalence remains unknown. Affected patients may experience neuroglycopenic and vegetative symptoms with different intensity typically within 3 h after carbohydrate intake [12]. Postbariatric hypoglycemia may lead to an impairment of quality of life and to increased food intake with subsequent weight regain [13].

Known risk factors for hypoglycemia in postbariatric patients are younger age, female gender, greater postoperative loss of weight, and pre-operative high insulin sensitivity [14–16]. The diagnosis of hypoglycemia is often demanding and requires fulfillment of Whipple’s triad often established with provocation testing [13, 14, 16–18]. These cumbersome and cost-intense tests require constant observation of the patient for several hours by health care professionals. Therefore, they should ideally only be performed in patients with a high a priori chance of hypoglycemia [17]. Furthermore, the lack of a reliable and simple screening tool may partly explain underdiagnosis of hypoglycemia in postbariatric patients [12].

We, therefore, investigated whether baseline parameters of postbariatric patients can predict the occurrence of symptomatic hypoglycemia during a mixed-meal test.

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

We evaluated all data of patients after bariatric surgery who underwent mixed-meal testing because of symptoms suspicious for postprandial hypoglycemia at the Clinic for Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism of the University Hospital Basel between May 2017 and October 2019, where approximately 100 patients undergo bariatric surgery annually. Patients are regularly followed up after bariatric surgery in our center. Participating patients presented with history of hypoglycemic symptoms and were therefore screened for this condition at our institution. In some of these patients, the provocation tests were also used as screening for a clinical trial (clinicaltrials.gov NCT03200782). Patients that underwent a MMT but also had diabetes mellitus (n = 1), gastric sleeve surgery (n = 1), or nesidioblastosis (n = 1) were excluded from analyses. All patients gave written informed consent for the use of their data.

Standardized Liquid Meal Test

Following an overnight fast, patients ingested a liquid 300 ml of mixed-meal drink containing 450 kcal and 60 g of carbohydrates (Ensure® Plus). Patients had to rest in a 45° upright position for the whole test. Heart rate and blood pressure were assessed at baseline. Every 30 min bedside glucose was measured, and venous blood samples were drawn to assess glucose, insulin, and C-peptide. Occurrence of hypoglycemic symptoms was monitored by checking for typical symptoms according to the Edinburgh Hypoglycemia scale and neurocognitive questions comprising repetitive questions for date of birth, current date, serial subtraction of seven-test, repeating words, and backward spelling of words. In patients presenting with symptomatic hypoglycemia during the test, 10 g of glucose were administered intravenously or orally depending on severity of the symptoms by a physician. If symptoms persisted, glucose was given repetitively until symptoms resolved and blood glucose normalized. The test was terminated after two consecutive measurements of blood glucose rising again after the initial postprandial drop or after 210 min without any hypoglycemic symptoms.

At baseline, insulin resistance was estimated using Homeostasis Model Assessment (HOMA and HOMA2) [19]. Several additional indices for insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion using the data assessed during the MMT were estimated: Whole-body Insulin Sensitivity Index, Oral Glucose Insulin Sensitivity, Predicted M-value, Insulin Secretion Index I, and Insulin Secretion Index II [20–24].

Statistical Analyses

Primary outcome of interest was the occurrence of symptomatic hypoglycemia during a standardized MMT, defined as low plasma glucose (< 3.4 mM) concurrent with typical symptoms, which can be relieved by glucose administration (Whipple’s triad). Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS® Statistics 25.0.0.2 (IBM®, Armonk, NY, USA) and Python 3.7.4 (Python Software Foundation, DE, USA) with publicly available software packages (pandas, NumPy, Matplotlib, scikit-learn, tableOne, statsmodels, SciPy). In figures, data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean and those given in tables are presented as median with interquartile range. Groups were compared using Kruskal-Wallis test. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were calculated for all continuous variables in the dataset. Areas under the curves (AUCs) of these ROC curves were calculated to identify most predictive variables. Univariate ROC analysis was chosen over multivariate logistic regression due to (i) the sample size, which was adequately powered for an univariate ROC with an alpha of 0.05 and a beta of 0.2, but not sufficient for a multivariate linear model, and (ii) due to the easy clinical applicability of ROC due to its intrinsic advantage of providing cutoffs for the examined predictors. Univariate logistic regression was additionally performed to provide odd ratios for all continuous variables. For the creation of the score, highly co-linear variables with a Spearman rank correlation coefficient > 0.6 were excluded by removing the variable with the smaller AUC in the ROC curve. Statistical significance threshold was p < 0.05.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of Patients

Thirty-five patients were included in the analyses, 19 patients (54%) presented with hypoglycemia, whereas in 16 patients (46%), the suspicion of hypoglycemia could not be confirmed by the MMT. Baseline characteristics of both groups are depicted in Table 1. Both groups exhibited comparable age, sex distribution, and BMI. All patients had undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. At baseline, the only significant differences between the groups were HbA1c and absolute and relative weight loss as compared to the weight pre-surgery (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics for patients without symptomatic hypoglycemia and with hypoglycemia after gastric bypass surgery

| Variable | Unit | Non-hypoglycemia | Hypoglycemia | p | Missing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 16 | 19 | |||

| Age | years | 40.8 (37.5, 47.8) | 42.9 (35.4, 51.0) | 0.947 | 0 |

| Years since surgery | years | 4.5 (2.9, 6.4) | 3.9 (1.7, 5.5) | 0.175 | 0 |

| Sex (female) | 14 (87.5) | 16 (84.2) | 1.000 | 0 | |

| T2DM pre-surgery | 2 (14.3) | 2 (12.5) | 1.000 | 5 | |

| T2DM current | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 | |

| Weight pre-surgery | kg | 109.5 (103.8, 121.5) | 116.2 (107.5, 129.5) | 0.296 | 0 |

| Weight current | kg | 78.5 (69.0, 91.0) | 78.7 (68.8, 82.5) | 0.619 | 0 |

| Absolute weight loss | kg | 29.0 (25.0, 35.2) | 39.0 (31.6, 53.5) | 0.024 | 0 |

| Relative weight loss | % | 28.3 (23.1, 30.8) | 35.0 (27.7, 45.6) | 0.024 | 0 |

| BMI pre-surgery | kg/m2 | 39.4 (38.1, 42.6) | 43.4 (39.8, 45.6) | 0.132 | 0 |

| BMI current | kg/m2 | 28.3 (25.8, 31.8) | 28.2 (24.7, 30.3) | 0.436 | 0 |

| Change in BMI | kg/m2 | 10.9 (9.7, 12.8) | 14.5 (10.9, 19.5) | 0.028 | 0 |

| Relative change in BMI | % | 28.3 (23.1, 30.8) | 35.0 (27.7, 45.6) | 0.024 | 0 |

| Systolic blood pressure | mmHg | 119.0 (115.5, 131.5) | 109.0 (100.0, 117.0) | 0.060 | 10 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | mmHg | 80.0 (68.8, 82.5) | 71.0 (68.0, 81.0) | 0.462 | 10 |

| Heart rate | min−1 | 74.5 (66.0, 81.2) | 72.0 (68.0, 80.0) | 0.723 | 10 |

| Baseline glucose | mmol/l | 4.7 (4.4, 4.8) | 4.5 (4.5, 4.7) | 0.485 | 12 |

| Baseline insulin | mU/l | 5.5 (3.5, 8.5) | 6.0 (4.3, 9.6) | 0.832 | 16 |

| Baseline C-peptide | pmol/l | 609.0 (519.8, 739.5) | 693.5 (579.8, 740.0) | 0.512 | 17 |

| HbA1c | % | 5.3 (5.0, 5.7) | 4.9 (4.7, 5.2) | 0.009 | 0 |

| Hemoglobin | g/l | 133.0 (126.8, 145.5) | 126.5 (122.2, 135.8) | 0.097 | 1 |

| C-reactive protein | mg/l | 0.6 (0.4, 2.0) | 0.7 (0.3, 1.6) | 0.637 | 1 |

| Glomerular filtration rate | ml/min/1.7 | 99.0 (86.2, 112.0) | 103.5 (99.2, 111.2) | 0.333 | 1 |

| HOMA-IR | 1.2 (0.7, 1.8) | 1.3 (0.9, 2.1) | 0.401 | 4 | |

| HOMA-beta | 81.3 (53.0, 124.2) | 127.7 (84.0, 159.4) | 0.139 | 4 | |

| HOMA2-IR | 1.3 (1.2, 1.5) | 1.4 (1.1, 1.5) | 0.808 | 4 | |

| HOMA2-beta | 132.1 (110.6, 150.1) | 138.8 (123.2, 153.2) | 0.612 | 4 |

p values were calculated with Kruskal-Wallis test or Fisher’s test. HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin A1c; HOMA, Homeostasis Model Assessment; IR, insulin resistance; PBH, postbariatric hypoglycemia; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus

Glucose Metabolism During Mixed-Meal Test

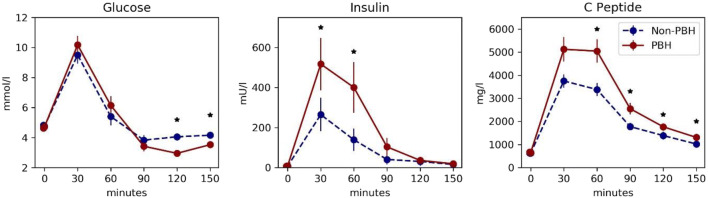

We compared plasma glucose, insulin, and C-peptide levels during the MMT (Fig. 1). Meal intake induced an exaggerated immediate stimulation in insulin and C-peptide leading to hypoglycemic levels after 120 min in patients with hypoglycemia compared to patients without hypoglycemia. Insulin resistance did not differ between groups, whereas insulin secretion assessed by HOMA-beta and insulin secretion indices was numerically increased, without reaching statistical difference (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Profiles for glucose, insulin, and C-peptide during a standardized mixed-meal test. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. n = 29–36 for each time point. *p < 0.05 with Kruskal-Wallis test. Red solid line patients with symptomatic hypoglycemia and dashed blue line patients without symptomatic hypoglycemia after gastric bypass surgery

Table 2.

Indices of insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity during mixed-meal tests

| Variable | Non-hypoglycemia | Hypoglycemia | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 12 | 18 | |

| Whole-body Insulin Sensitivity Index [22] | 103.5 (91.1, 120.6) | 72.8 (43.1, 115.6) | 0.099 |

| Oral Glucose Insulin Sensitivity [23] | 475.5 (457.4, 510.1) | 483.0 (393.1, 531.9) | 0.966 |

| Predicted M-value [24] | 2.4 (2.1, 2.4) | 2.6 (2.2, 2.7) | 0.225 |

| Insulin Secretion Index I [20] | 41.5 (35.7, 66.7) | 55.2 (40.8, 95.6) | 0.310 |

| Insulin Secretion Index II [21] | 20.5 (15.5, 31.4) | 32.3 (20.1, 48.8) | 0.189 |

p values were calculated with Kruskal-Wallis test

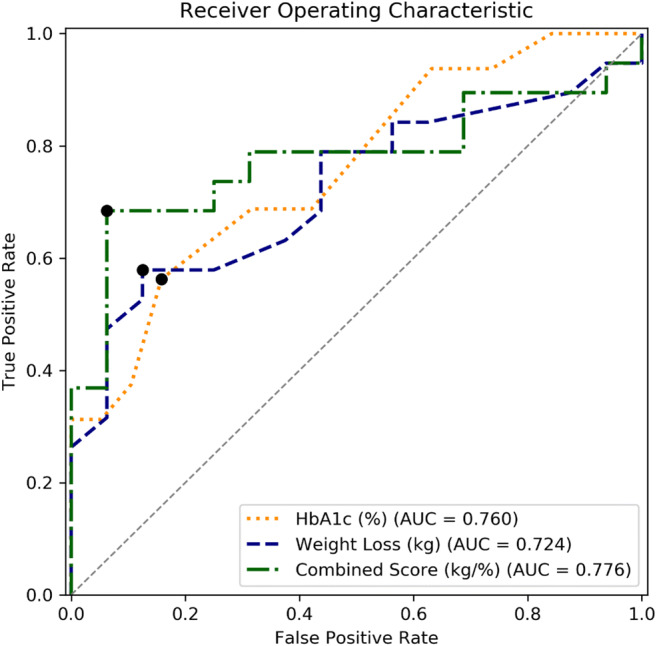

Prediction of Occurrence of Postprandial Hypoglycemia

Based on our findings from univariate group comparisons and all continuous variables’ AUCs from univariate ROC curves (Supplemental Table 1), we identified HbA1c and absolute weight loss as the most predictive parameters for occurrence of postprandial hypoglycemia in our dataset. Both variables achieved acceptable performance in ROC analyses (Fig. 2) with optimal cutoffs for HbA1c at 5.3% (sensitivity 56%, specificity 84%) and weight loss of 38.2 kg (sensitivity 58%, specificity 88%), respectively (Supplemental Table 2). However, a combined score of the two variables, calculated as the ratio of absolute weight loss (in kg) to current HbA1c (in %), achieved the highest AUC of 0.784, using 7.2 (kg/%) as a cutoff and achieving a sensitivity of 68% and a specificity of 94% at the local maximum.

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curves. Curves are plotted with local optima, defined as the maximum of the true positive rate minus the false positive rate. The HbA1c curve is displayed inversely for comparison. The combined score was calculated as the ratio of absolute postoperative weight loss (kg) by HbA1c (%)

Discussion

It is presumed that the overall prevalence of hypoglycemia in postbariatric patients is underestimated [7, 9]. One reason for this is the lack of standardized, practicable, and affordable screening tests. We demonstrate that in patients with suspected hypoglycemia, a score using HbA1c and the postoperative weight loss is able to identify patients at risk for symptomatic hypoglycemia during an MMT. We further depict baseline and in-test differences of patients with and without hypoglycemia. These observations might ease future screening for hypoglycemia in patients after gastric bypass surgery.

By performing an MMT with repeated measurement of glucose, insulin, and C-peptide, we could confirm the pathognomonic pattern of postbariatric hypoglycemia in our study cohort: in patients with hypoglycemia, insulin and C-peptide increased drastically compared to patients without hypoglycemia, whereas glucose levels lowered markedly in the hypoglycemia group. With both groups starting from similar baseline values, these data also confirm the exclusively postprandial occurrence of hyperinsulinemia in the hypoglycemia group. These findings contrast previous studies reporting insignificant differences in postprandial glucose and insulin profiles between postbariatric patients with and those without postprandial symptoms [25, 26]. One possible explanation might be the larger number of patients in our cohort.

We used different indices for an estimation of insulin secretion capacity and insulin sensitivity, which did not indicate significant differences between patients with and without hypoglycemia regarding these parameters. This contrasts findings from a recent study by Raverdy et al. that suggested beta-cell function and insulin sensitivity might differentiate patients with and without hypoglycemia [14]. This difference to our study might result from the use of an oral glucose tolerance test in their study in contrast to a mixed-meal test in ours. Interpreting this is difficult due to the fact that none of these indices have been designed for postbariatric patients, hinting towards the need for more precise tools in these patients.

The outcome of interest for this study was the occurrence of late dumping, i.e., Whipple’s triad, during a standardized MMT. This way, our study population’s hypoglycemia status is well-characterized as opposed to large cohort or register studies, which define hypoglycemia by past diagnosis. In contrast to previous studies, age, sex, and fasting glucose did not distinguish patients with and without hypoglycemia in our study [11, 16, 27]. Higher preoperative insulin sensitivity may be another risk factor but was not assessed in this cohort [11]. In our trial cohort, lower HbA1c and higher absolute weight loss clearly distinguished patients with and without PBH. Low HbA1c could be explained by multiple episodes of hypoglycemia during the months before testing; however, it has not been reported in hypoglycemia patients yet. Greater weight loss in hypoglycemia patients has been reported in previous studies [14, 15, 27, 28] and might overstrain metabolic adaptations after bariatric surgery, especially when occurring over a short period, leading to postprandial overexcretion of insulin. The mechanisms of this oversecretion appear to be multifactorial [29], and as recently discovered also mediated by interleukin 1-β [30].

At baseline, systolic blood pressure tended to be lower in patients with hypoglycemia. This might be driven by increased vagal activity or reflect lower concentrations of stress hormones preventing hypoglycemia in these patients. However, as using a single blood pressure measurement for screening is not recommendable due to possible fluctuation, we did not follow up on this in final ROC analyses.

While both HbA1c and weight loss achieved decent AUCs in the ROC analysis, combining the two into a score an even higher AUC of 0.776 was achieved. The score was calculated by dividing absolute weight loss by HbA1c. One of the major strengths of this score is its easy and wide applicability, as these parameters are usually assessed postsurgery in bariatric patients and HbA1c can be measured in most labs worldwide. By assessing medical history, hypoglycemia-related symptoms, and the score together in postbariatric patients, MMTs may be performed more targeted in the future.

Limitations

One possible limitation of this study is the use of a liquid mixed-meal test with fixed carbohydrate loads as opposed to body weight adapted loads. However, the current body weight was not predictive for the occurrence of symptomatic hypoglycemia and the median weight was similar in patients of both groups. These data do not suggest that baseline body weight had a relevant effect on the outcome of the MMT. However, the main limitation is the relatively small single center dataset, which limited the statistical analyses to be adequately performed, as well as the lack of a validation cohort. Therefore, our results and the proposed scoring system will require future studies to confirm their external validity, clinical applicability, and generalizability.

Conclusion

HbA1c, absolute, and relative postoperative weight loss differ at baseline in postbariatric patients with versus without symptomatic hypoglycemia during a standardized mixed-meal test. A proposed score of postoperative weight loss divided by HbA1c could predict the occurrence of PBH in a mixed-meal test. Future studies will provide insights into the generalizability of these results and the practicability of a wide use of our score as a screening tool in postbariatric patients.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 27 kb)

Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under the curve

- HbA1c

Glycosylated hemoglobin A1c

- MMT

Mixed-meal test

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Universität Basel (Universitätsbibliothek Basel).

Declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and local ethics research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Elric Zweck and Matthias Hepprich contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

References

- 1.Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, Formisano G, Buchwald H, Scopinaro N. Bariatric surgery worldwide 2013. Obes Surg. 2015;25(10):1822–1832. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1657-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welbourn R, Hollyman M, Kinsman R, Dixon J, Liem R, Ottosson J, Ramos A, Våge V, al-Sabah S, Brown W, Cohen R, Walton P, Himpens J. Bariatric surgery worldwide: baseline demographic description and one-year outcomes from the Fourth IFSO Global Registry Report 2018. Obes Surg. 2019;29(3):782–795. doi: 10.1007/s11695-018-3593-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng J, Gao J, Shuai X, Wang G, Tao K. The comprehensive summary of surgical versus non-surgical treatment for obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Oncotarget. 2016;7(26):39216–39230. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sjostrom L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, Torgerson J, Bouchard C, Carlsson B, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(26):2683–2693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bray GA, Frühbeck G, Ryan DH, Wilding JPH. Management of obesity. The Lancet. 2016;387(10031):1947–1956. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)00271-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen NT, Varela JE. Bariatric surgery for obesity and metabolic disorders: state of the art. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(3):160–169. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gribsholt SB, Pedersen AM, Svensson E, Thomsen RW, Richelsen B. Prevalence of self-reported symptoms after gastric bypass surgery for obesity. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(6):504–511. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.5110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazar LO, Sapojnikov S, Pines G, et al. Symptomatic and asymptomatic hypoglycemia post three different bariatric procedures: a common and severe complication. Endocr Pract. 2019; 10.4158/EP-2019-0185. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Capristo E, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, Spuntarelli V, Bellantone R, Giustacchini P, et al. Incidence of Hypoglycemia after gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy: a randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(6):2136–2146. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-01695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marsk R, Jonas E, Rasmussen F, Naslund E. Nationwide cohort study of post-gastric bypass hypoglycaemia including 5,040 patients undergoing surgery for obesity in 1986-2006 in Sweden. Diabetologia. 2010;53(11):2307–11. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1798-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee CJ, Clark JM, Schweitzer M, Magnuson T, Steele K, Koerner O, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for hypoglycemic symptoms after gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015;23(5):1079–1084. doi: 10.1002/oby.21042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patti M-E, Goldfine AB. The rollercoaster of post-bariatric hypoglycaemia. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2016;4(2):94–96. doi: 10.1016/s2213-8587(15)00460-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malik S, Mitchell JE, Steffen K, Engel S, Wiisanen R, Garcia L, et al. Recognition and management of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia after bariatric surgery. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2016;10(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raverdy V, Baud G, Pigeyre M, Verkindt H, Torres F, Preda C, Thuillier D, Gélé P, Vantyghem MC, Caiazzo R, Pattou F. Incidence and predictive factors of postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a five year longitudinal study. Ann Surg. 2016;264(5):878–885. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nielsen JB, Pedersen AM, Gribsholt SB, Svensson E, Richelsen B. Prevalence, severity, and predictors of symptoms of dumping and hypoglycemia after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(8):1562–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belligoli A, Sanna M, Serra R, Fabris R, Pra’ CD, Conci S, et al. Incidence and predictors of hypoglycemia 1 year after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2017;27(12):3179–3186. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2742-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emous M, Ubels FL, van Beek AP. Diagnostic tools for post-gastric bypass hypoglycaemia. Obes Rev. 2015;16(10):843–856. doi: 10.1111/obr.12307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scarpellini E, Arts J, Karamanolis G, Laurenius A, Siquini W, Suzuki H, et al. International consensus on the diagnosis and management of dumping syndrome. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16(8):448–66. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-0357-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(6):1487–1495. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips DI, Clark PM, Hales CN, Osmond C. Understanding oral glucose tolerance: comparison of glucose or insulin measurements during the oral glucose tolerance test with specific measurements of insulin resistance and insulin secretion. Diabet Med. 1994;11(3):286–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1994.tb00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wareham NJ, Phillips DI, Byrne CD, Hales CN. The 30 minute insulin incremental response in an oral glucose tolerance test as a measure of insulin secretion. Diabet Med. 1995;12(10):931. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1995.tb00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(9):1462–1470. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.9.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mari A, Pacini G, Murphy E, Ludvik B, Nolan JJ. A model-based method for assessing insulin sensitivity from the oral glucose tolerance test. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(3):539–548. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.3.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tura A, Chemello G, Szendroedi J, Gobl C, Faerch K, Vrbikova J, et al. Prediction of clamp-derived insulin sensitivity from the oral glucose insulin sensitivity index. Diabetologia. 2018;61(5):1135–1141. doi: 10.1007/s00125-018-4568-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim SH, Liu TC, Abbasi F, Lamendola C, Morton JM, Reaven GM, McLaughlin TL. Plasma glucose and insulin regulation is abnormal following gastric bypass surgery with or without neuroglycopenia. Obes Surg. 2009;19(11):1550–1556. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9893-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laurenius A, Werling M, Le Roux CW, Fandriks L, Olbers T. More symptoms but similar blood glucose curve after oral carbohydrate provocation in patients with a history of hypoglycemia-like symptoms compared to asymptomatic patients after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(6):1047–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brix JM, Kopp HP, Hollerl F, Schernthaner GH, Ludvik B, Schernthaner G. Frequency of hypoglycaemia after different bariatric surgical procedures. Obes Facts. 2019;12(4):397–406. doi: 10.1159/000493735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee CJ, Wood GC, Lazo M, Brown TT, Clark JM, Still C, et al. Risk of post-gastric bypass surgery hypoglycemia in nondiabetic individuals: a single center experience. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016;24(6):1342–1348. doi: 10.1002/oby.21479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salehi M, Vella A, McLaughlin T, Patti ME. Hypoglycemia after gastric bypass surgery: current concepts and controversies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(8):2815–2826. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-00528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hepprich M, Wiedemann SJ, Schelker BL, Trinh B, Starkle A, Geigges M, et al. Postprandial Hypoglycemia in patients after gastric bypass surgery is mediated by glucose-induced IL-1beta. Cell Metab. 2020;31(4):699–709. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 27 kb)