Abstract

This study is aimed at exploring undergraduate students’ abilities to recognize anxiety disorder and depression symptoms, and their literacy of mental first-aid supports for these problems. Using a mixed-method, cross-sectional design, data were collected from 724 undergraduate students in Hanoi. This used a questionnaire on literacy of anxiety disorder and depression, adapted from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health Literacy and Stigma. The prevalence of the respondents who could identify anxiety disorder and depression symptoms were 25.9% and 42.3%, respectively. Literacy of mental first-aid supports focused on: listening to the person in an understanding way, encouraging the person to be more active, seeking professional help, make appointment with the general doctor.

Keywords: anxiety disorder, depression, mental health literacy, Vietnam, young people

Introduction

Mental disorders account for 13% of the global burden of disease, and its prevalence appears to be increasing (WHO, 2012). The results from the Burden of Disease and Healthy Aging study in 2019 showed that mental disorders in Vietnam represented 4.93% of total DALYs (Disability Adjusted Life Year) (Khuê and Hương, 2019). In Vietnam, the prevalence of general mental health problems among young people, a group which includes university students, ranges from 25% to 60% (Ăng et al., 2011; Huyền and Quỳnh, 2011).

The term “mental health literacy” (MHL) was first used to describe “knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders which aid their recognition, management, or prevention” (Jorm et al., 1997). This definition emphasizes the role of recognition of mental disorders, and help-seeking for management and prevention. Studies showed that many young people have poor MHL (Cotton et al., 2006; Kelly et al., 2006; Loureiro et al., 2013; Melas et al., 2013; Reavley and Jorm, 2011). Recognition of social anxiety disorder is quite low, even in the developed countries like in the UK (19%) (Furnham et al., 2014), Australia (3%–16%) (Jorm, 2011; Jorm et al., 2007; Reavley and Jorm, 2011), and in the United States (28%) (Olsson and Kennedy, 2010). Recognition of depression seemed higher (42%) (Olsson and Kennedy, 2010) and higher still among medical student population (Liu, 2019; Sayarifard et al., 2015). However, in Asian country such as Sri Lanka, only 17.4% of 4617 respondents were able to recognize depression (Amarasuriya et al., 2015).

In Vietnam, a study carried out in 2015 among university students showed that 61.7% public health students and 38.3% sociology students were able to recognize anxiety disorder (Nguyen Thai and Nguyen, 2018). The percentage of students that could label depression correctly was 69% for public health, and 31% for sociology (Nguyen Thai and Nguyen, 2018). Hương and Minh (2017) examined 559 third year students studying technical, economic, social sciences, or health science majors and 29.7% of them were able to accurately define some mental disorders terms such as social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and majyor depression (Hương and Minh, 2017). As mental health problems often arise at young age, such studies are needed to improve the effectiveness of potential mental health interventions for young people (WHO, 2013). In order to have more evidence for intervention, this paper aims to investigate how university students who perform well MHL are able to recognize anxiety disorder and depression, and how they came to know about first-aid activities to support people with anxiety disorder and depression.

Methods

Settings, study design, and sampling

This was a cross-sectional, mixed-methodology (quantitative and qualitative) study, conducted in the Faculty of Sociology at two universities: University of Social Sciences and Humanities (USSH) and Academy of Journalism and Communication (AJC). The survey was carried out between September 2017 and May 2018.

Cluster sampling from years 1 and 4 was used because it was convenient. Students were chosen by cluster; each class was one cluster, and there were four classes. The total sample was 724 students. Four group discussions (two in USSH and two in AJC) were also carried out with 32 respondents.

Research instruments

The structured questionnaire consisted of two parts: the MHL of anxiety disorder and depression, and socio-demographic information. Literacy of anxiety disorder and depression were assessed using a questionnaire adapted from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health Literacy and Stigma (Jorm, 2011). The survey started with two vignettes: one of a 20-year-old female student showing signs of anxiety disorder and the other of a 20-year-old male student, who was exhibiting symptoms of depression. Questions focused on recognition of the problem and knowledge of first-aid support. This MHL instrument has been used in many studies in different countries and had been validated (Reavley et al., 2014). Permission to use the MHL questionnaire was granted by A.F. Jorm and his team. The questionnaire was translated into Vietnamese. To test the structural validity of the questionnaire, it was piloted with 10 students to ensure that the questions were clearly written and that they produced appropriate answers. Additionally, the questionnaire was reviewed by two mental health experts in Hanoi, first one from the National Institute of Mental Health and the other one from the Psychiatric Faculty, Hanoi Medical University. Feedback was used to modify the vignettes and improve some structural and content validity issues with some items in the questionnaire.

To assess recognition of the problem from the two vignettes, the question: “In your opinion, what is going on with the person?” was asked. The response format was multiple choice with names of some mental health problems. The correct answers to the two vignettes were “anxiety disorder” and “depression.”

To assess knowledge of first-aid to support, the respondent was asked to imagine that they knew the person in the vignette and the following actions were listed:

Listen to her/his problem in an understanding way

Talk to her/him firmly about getting her/his act together

Suggest her/him seeking professional help

Make an appointment for her/him to see a GP

Rally friends to cheer her/him up

Keep her/him busy to keep her/his mind of the problems

Encourage her/him to become more physically active

Ignoring her/him until she/he gets over it

For each action, the respondent was asked to categorize each of the options as:

Helpful

Harmful

Neither

Don’t know

Data collection, analysis, and ethical considerations

Data were collected in classrooms. Each student was given a questionnaire which additionally contained a study information sheet and a consent form. They were asked to read the study information sheet, sign the consent form if they agreed to participate in the study, and then answered the questionnaire. Before collecting the data, the students were informed that they either could stay inside to complete the questionnaire or go outside if choosing not to participate in the survey. At the time the completed questionnaire was collected, it was clearly stated again that participation in the survey was voluntary. This information was also included on the consent form. 100% of students presented at the data collection stage agreed to answer the questionnaire. After the survey was administered in each university, the questionnaires were checked for completeness. The response rate was 98% (724/736) and all of 724 completed questionnaires were included in the analysis. The statistical software package Stata 14 was used for statistical analyzes. Frequencies of multiple variables were calculated, and Chi squared tests were conducted to test for statistical differences between the two groups of students (by university and by correct recognition of the problems). Group discussions were transcripted and analyzed by themes, no software was used.

The protocol of this study was approved by the Scientific and Ethical Committee in Biomedical Research, Hanoi University of Public Health under Decision No. 366/2017/YTCC-HD3.

Results

Among 724 questionnaires included in the analysis, 446 (61.6%) were students from USSH and 278 (38.4%) were from AJC. Table 1 shows that the majority of respondents were female (81.6%). Most of them were living with a roommate/housemate (45.3%) or with family (35.2%). 7.7% were living by themselves.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents (n = 724).

| No. | USSH n (%) | AJC n (%) | Total n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gender | |||

| Male | 82 (18.6) | 50 (18.2) | 132 (18.4) | |

| Female | 395 (81.4) | 225 (81.8) | 620 (81.6) | |

| 2 | Living with | |||

| Alone | 38 (8.6) | 17 (6.2) | 55 (7.7) | |

| Family | 146 (33.1) | 106 (38.5) | 252 (35.2) | |

| Relatives | 22 (5.0) | 17 (6.2) | 39 (5.4) | |

| Roommates/housemates | 206 (46.7 | 118 (42.9) | 324 (45.3) | |

| Partners | 7 (1.6) | 4 (1.5) | 11 (1.5) | |

| Acquaintances | 9 (2.0) | 10 (3.6) | 19 (2.7) | |

| Others | 13 (2.9) | 3 (1.1) | 16 (2.2) | |

Recognition of anxiety disorder and depression

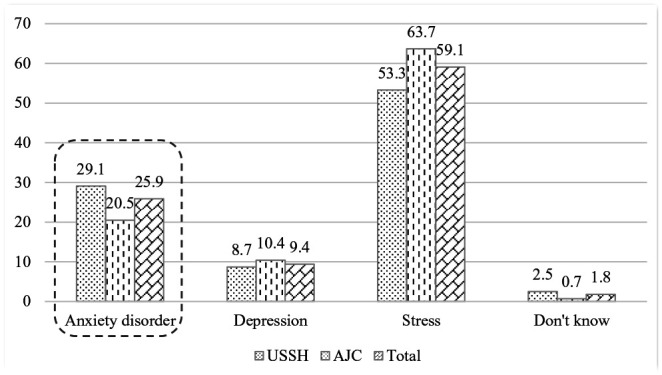

The percentage of students who correctly identified anxiety disorder was 25.9%, 29.1% were USSH students and 20.5% were from AJC (Figure 1). There was no significant difference between the two groups (χ2 = 15.8; p = 0.07). With the symptoms in anxiety disorder vignette, nearly 60% of the respondents (USSH: 53.3%; AJC: 63.7%) incorrectly identified this as stress.

Figure 1.

Identification of anxiety disorder (n = 724).

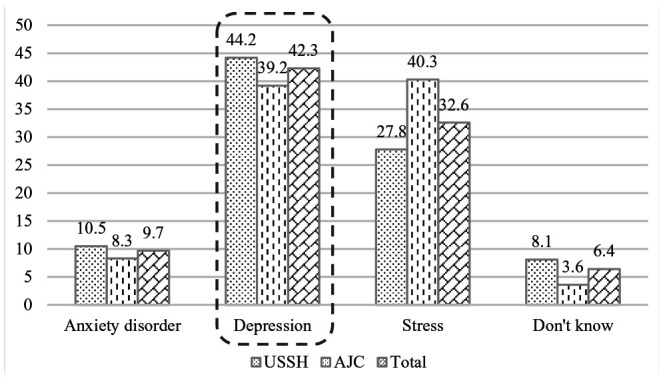

Figure 2 shows the percentage of students in two universities who could identify depression (42.3%) and the result was higher than that of anxiety disorder (USSH: 44.2%; AJC: 39.2%). This result was statistically different (χ2 = 31.2; p = 0.001). In addition to depression, 32.6% of the respondents called it stress.

Figure 2.

Identification of depression (n = 724).

To assess knowledge of mental first-aid to support for anxiety disorder and depression, a list of actions was provided (see Table 2). The four actions rated as most “helpful” for anxiety disorder were:

Table 2.

Percentage of the respondents rated first-aid to support as “helpful” for the two problems.

| Recognized the problem-Group 1 (n = 187) % (95% CI) | Failed to recognize the problem-Group 2 (n = 537) % (95% CI) | Total (n = 724) % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety disorder | |||

| 1. Listen to her problem in an understanding way | 96.7 (92.9–98.5) | 96.4 (94.5–97.7) | 96.5 |

| 2. Encourage her to be more physically active | 79.6 (73.2–84.8) | 79.7 (76.0–82.9) | 79.6 |

| 3. Suggest her seek professional help | 75.4 (68.6–81.0) | 78.8 (75.0–82.3) | 77.1 |

| 4. Make an appointment for her to see the GP | 65.5 (55.3–69.2) | 70.7 (66.7–74.4) | 68.1 |

| 5. Rally friends to cheer her up | 47.5 (40.4–54.8) | 48.9 (44.7–53.2) | 48.2 |

| 6. Keep her busy to keep her mind of the problems | 10.6 (6.9–16.0) | 10.6 (8.2–13.5) | 10.6 |

| 7. Talk to her firmly about getting her act together | 9.0 (5.7–14.1) | 8.9 (6.7–11.6) | 8.9 |

| 8. Ignoring her until she gets over it | 3.2 (1.4–7.0) | 4.4 (3.0–6.5) | 3.8 |

| Depression | |||

| 9. Listen to his problem in an understanding way | 96.2 (92.3–98.2) | 95.9 (93.8–97.2) | 96.0 |

| 10. Encourage him to be more physically active | 82.3 (76.1–87.2) | 86.0 (82.8–88.7) | 84.1 |

| 11. Suggest him seek professional help | 82.3 (76.1–87.2) | 78.7 (75.0–82.0) | 80.5 |

| 12. Make an appointment for him to see the GP** | 76.4 (69.7–82.0) | 75.4 (71.5–78.8) | 75.9 |

| 13. Rally friends to cheer him up | 64.1 (56.9–70.7) | 60.3 (56.1–64.4) | 62.2 |

| 14. Keep him busy to keep his mind of the problems | 10.1 (6.5–15.4) | 15.0 (12.2–18.3) | 12.5 |

| 15. Talk to him firmly about getting his act together* | 10.6 (6.9–16.0) | 15.4 (12.6–18.7) | 13.0 |

| 16. Ignoring him until he gets over it* | 3.2 (1.4–7.0) | 6.8 (5.0–9.3) | 5.0 |

p < 0.05. **p < 0.01.

Listen to her problem in an understanding way (96.5%)

Encourage her to be more physically active (79.6%)

Suggest her seek professional help (77.1%)

Make an appointment for her to see the GP (68.1%)

Two first-aid actions listed a “harmful” by the respondents were:

Talk to her firmly about getting her act together (8.9%)

Ignoring her until she gets over it (3.8%)

However, only a small number of respondents in two groups still chose these actions as being helpful (p > 0.05).

For depression, highest rated “helpful” first-aid support actions chosen by two groups were the same as for anxiety disorder; however, the percentages were different:

Listen to his problem in an understanding way (96%)

Encourage him to be more physically active (84.1%)

Suggest him seek professional help (80.5%)

Make an appointment for him to see the GP (75.9%)

Group 1 chose make an appointment for him to see the GP as being a helpful action with higher percentage than group 2 (χ2 = 16.1; p < 0.01). Group 2 identified two harmful first-aid support actions: talk to him firmly about getting his act together and ignoring him until he gets over it with higher percentage than group 1 (χ2 = 9.6; p < 0.05 andχ2 = 10.1; p < 0.05).

During group discussions, respondents were quite opened to discussing what they knew about mental health problems, including anxiety disorder and depression.

“None of them tells us that they are in trouble. I realize they are not as usual, sit alone, no talk with friends, I come and talk to them. At first, she said nothing wrong, but I kept talking then she began to tell about what made her worried. Study, extra work for money so her parents don’t have to send her money. . . Many other things” (FGD1-USSH)

“I read some writings on Beautiful Mind Viet Nam so I know these two problems. I read them to see how I can help myself or my friends. People with depression left alone are easy to kill themselves, aren’t they?” (FGD1-AJC)

“If you ask me whether I can do anything if my friends have symptoms like you said, honestly I don’t. They don’t want to talk with me. I ask but they refuse to talk, what can I do? But I think I will call their parents because parents need to know how their children do at the university, do they have any difficulties. I don’t think they can overcome their problems if we leave them alone. I don’t know exactly what I should do, but I think I have to something to help” (FGD2-USSH)

Discussion

Being able to identify mental health problems is one of the most important elements to assess knowledge of mental health and can facilitate help-seeking (Wright et al., 2007). The percentage of young Vietnamese people in this study could identify anxiety disorder at higher rate (25.9%) than in UK (Furnham et al., 2014), and Australia (Jorm, 2011; Jorm et al., 2007; Reavley and Jorm, 2011), but at a lower rate than in the US (Olsson and Kennedy, 2010). Recognition of depression among our respondents was 42.3%, at a higher rate than in Iran, Sri Lanka and Vietnam (Amarasuriya et al., 2015; Hương and Minh, 2017; Nguyen Thai and Nguyen, 2018; Sayarifard et al., 2015) and at the same rate as general young people in the US (Olsson and Kennedy, 2010), but at a lower rate than nursing students (Liu, 2019). Our result also showed a majority of respondents incorrectly identified anxiety disorder vignette as “stress” (59.1%); meanwhile the percentage of respondents who incorrectly identified depression vignette as “stress” was only 32.6%. This result shows that young people in general, and Vietnamese students in particular, need to be provided with knowledge of anxiety disorder and depression symptoms, with more focus put on anxiety disorder. This was understandable because recently depression was mentioned on some social network like Facebook, Zing, etc., where young people often spent time surfing for information, including depression.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) anxiety disorder and depression are common mental disorders in many countries (WHO, 2017b). Depression can lead to suicide (National Institute of Mental Health, 2018; WHO, 2017a, 2018). Correct identification of the problems could assist individuals in help-seeking behaviors and give them a better chance of early treatment (Liu, 2019). The percentage of respondents, who could recognize anxiety disorder and depression, in this study was low; however, a majority of them identified these two problems were among common mental disorders—stress (94.3% and 84.6%). Only 1.8% of them could not recognize anxiety disorder vignette as mental disorder and for depression vignette, this percentage was 6.4%.

Even though the percentage of correct identification of anxiety disorder and depression in this study were low; most of the respondents were willing to offer help these two problems (91.2% for anxiety disorder; 90.7% for depression). This result is consistent with that reported by Reavley et al. (2012). This finding indicates that young people are willingness to help those with anxiety disorder and depression, whether or not they can correctly recognize the specific problems. Moreover, if young people have their MHL improved, they have more confidence in supporting others as indicated in FGD. This result is also mentioned in the work of Kelly et al. (2007).

In terms of knowledge about mental first-aid support, among the suggested possible actions that participants could hypothetically take to support people with anxiety disorder and depression, the option of listening to the person who needs help was chosen by a large percentage of respondents (96.5% for anxiety disorder; 96% for depression). This action is consistent with mental health first aid guidelines published by Kelly et al. (2011). In 2017, WHO’s message for the World Health Day was “Depression—Let’s talk” (WHO, 2017a). This means listening and talking are considered helpful first-aid to support depression as well as anxiety disorder (Mạng lưới Hiểu biết về SKTT của Việt Nam, 2019). Encourage the person to be physically active was another first-aid support chosen by the respondents. They believed if sufferers from mental illness are encouraged to participate in some physical activities, they could be helped to overcome their negative emotions, although it might only bring temporary results. In this study, only 3.2% respondents who recognized depression, and 6.8% of those who did not recognize depression, chose to ignore the person until he gets over the problem (p < 0.05). This percentage was low; however, it reflects the fact that some Vietnamese young people have erroneous or inaccurate knowledge of mental health first-aid to support people suffering from mental issues. Therefore, interventions to improve MHL should focus on the message that depression people should not be left alone. The WHO has confirmed that anxiety disorder and depression, especially depression, is best combated when it is detected early and when patients receive early treatment, which often prevent people with depression from taking their lives (WHO, 2018).

Conclusions

The percentage of the respondents who could recognize anxiety disorder and depression in this study was 25.9% and 42.3%. There was a worrying high number of the respondents who identified these two problems were stress. The most commonly rated-as-helpful actions for mental first-aid for both problems were: listen to the problem in an understanding way, encourage the person to be more physically active, suggest the person seek professional help, make an appointment for the person to see the GP. There was a small percentage of the respondents chose to ignore the person until he/she gets over the problem as first-aid support. Incorrect mental first-aid could be very damaging, so even a low percentage of very poor MHL could be dangerous. Our findings suggest a need to improve MHL of anxiety disorder and depression, especially in detection/identification and how to provide support, for Vietnamese undergraduate students. Although mental health problems have become an increasing problem across all socio-demographic groups in Vietnam, there are currently not enough interventions to educate the public about them. Mental health has never been considered high priority in Vietnam. Further studies should focus on MHL of other mental disorders among different social groups. Furthermore, mental health education should be disseminated among young people by implementing interventions with different approaches.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Nguyen Thai Quynh-Chi  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3112-8707

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3112-8707

References

- Amarasuriya SD, Jorm AF, Reavley NJ. (2015) Quantifying and predicting depression literacy of undergraduates: A cross sectional study in Sri Lanka. BMC Psychiatry 15(1): 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ăng TN, Dũng ĐV, Quỳnh HHN. (2011) Tỷ lệ rối nhiễu tâm trí và các yếu tố liên quan của sinh viên khoa Y tế công cộng Đại học Y Dược TP. Hồ Chí Minh năm 2010. Tạp chí Y học TP. Hồ Chí Minh 15: 6. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton SM, Wright A, Harris MG, et al. (2006) Influence of gender on mental health literacy in young Australians. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 40(9): 790–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnham A, Annis J, Cleridou K. (2014) Gender differences in the mental health literacy of young people. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health 26(2): 283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hương LTT, Minh ĐH. (2017) Tình trạng sức khỏe tâm thần và hiểu biết về sức khỏe tâm thần của sinh viên tại Hà Nội. Kỷ yếu hội thảo quốc tế Tâm lý học khu vực Đông Nam Á lần thứ nhất “Hạnh phúc con người và phát triển bền vững”. Hà Nội: Nhà xuất bản Đại học Quốc gia Hà Nội, p.10. [Google Scholar]

- Huyền LT, Quỳnh HHN. (2011) Tình trạng stress của sinh viên Y tế công cộng Đại học Y Dược thành phố Hồ Chí Minh và một số yếu tố liên quan năm 2010. Tạp chí Y học TP. Hồ Chí Minh 15: 6. [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF. (2011) National Survey of Mental Health Literacy and Stigma. Commonwealth of Australia, Melbourne: University of Melbourne. [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, et al. (1997) “Mental health literacy”: A survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. The Medical Journal of Australia 166(4): 182–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Wright A, Morgan AJ. (2007) Beliefs about appropriate first aid for young people with mental disorders: Findings from an Australian national survey of youth and parents. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 1(1): 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly CM, Jorm AF, Rodgers B. (2006) Adolescents’ responses to peers with depression or conduct disorder. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 40(1): 63–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly CM, Jorm AF, Wright A. (2007) Improving mental health literacy as a strategy to facilitate early intervention for mental disorders. The Medical Journal of Australia 187(S7): 26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly CM, Mithen JM, Fischer JA, et al. (2011) Youth mental health first aid: A description of the program and an initial evaluation. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 5(1): 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khuê LN, Hương NT. (2019) Gánh nặng bệnh tật và tuổi thọ khỏe mạnh: Khái niệm, phương pháp và kết quả của Việt Nam giai đoạn 2008–2017. Nhà xuất bản Y học. [Google Scholar]

- Liu W. (2019) Recognition of, and beliefs about, causes of mental disorders: A cross-sectional study of US and Chinese undergraduate nursing students. Nursing and Health Sciences 21(1): 28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro LM, Jorm AF, Mendes AC, et al. (2013) Mental health literacy about depression: A survey of Portuguese youth. BMC Psychiatry 13(1): 129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mạng lưới Hiểu biết về SKTT của Việt Nam (2019) Tổng quan về rối loạn lo âu. Available at: http://vnmentalhealth.edu.vn/cac-roi-loan-lo-au?fbclid=IwAR38Y_1JArOGFyRSbBaQDPSCGSprnLH7ZycDLD_dKPs6RvCKULV8ENTFJoo (accessed 25 August 2019).

- Melas PA, Tartani E, Forsner T, et al. (2013) Mental health literacy about depression and schizophrenia among adolescents in Sweden. European Psychiatry 28(7): 404–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health (2018) What is depression? Available at: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/depression/index.shtml (accessed 14 July 2019).

- Nguyen Thai QC, Nguyen TH. (2018) Mental health literacy: Knowledge of depression among undergraduate students in Hanoi, Vietnam. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 12(1): 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson DP, Kennedy MG. (2010) Mental health literacy among young people in a small US town: Recognition of disorders and hypothetical helping responses. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 4(4): 291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reavley NJ, Jorm AF. (2011) Young people’s recognition of mental disorders and beliefs about treatment and outcome: Findings from an Australian national survey. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 45(10): 890–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reavley NJ, McCann TV, Jorm AF. (2012) Mental health literacy in higher education students. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 6(1): 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reavley NJ, Morgan AJ, Jorm AF. (2014) Development of scales to assess mental health literacy relating to recognition of and interventions for depression, anxiety disorders and schizophrenia/psychosis. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 48(1): 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayarifard A, Ghadirian L, Mohit A, et al. (2015) Assessing mental health literacy: What medical sciences students’ know about depression. Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran 29: 161. eCollection 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2012) Make a difference in the lives of people with mental disorders. Available at: http://www.who.int/mental_health/mental_health_flyer_2012.pdf?ua=1 (accessed 13 May 2019).

- WHO (2013) 10 facts on mental health. Available at: http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/mental_health_facts/en/? (accessed 13 May 2019).

- WHO (2017. a) Depression. Available at: http://www.who.int/topics/depression/en/ (accessed 13 May 2019).

- WHO (2017. b) Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization, p.24. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2018) Depression: Key facts. Available at: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed 21 June 2018).

- Wright A, Jorm AF, Harris MG, et al. (2007) What’s in a name? Is accurate recognition and labelling of mental disorders by young people associated with better help-seeking and treatment preferences? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 42(3): 244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]