Abstract

Infrared nano-spectroscopy based on scattering-type scanning near-field optical microscopy (s-SNOM) is commonly employed to probe the vibrational fingerprints of materials at the nanometer length scale. However, due to the elongated and axisymmetric tip shank, s-SNOM is less sensitive to the in-plane sample anisotropy in general. In this article, we report an easy-to-implement method to probe the in-plane dielectric responses of materials with the assistance of a metallic disk micro-antenna. As a proof-of-concept demonstration, we investigate here the in-plane phonon responses of two prototypical samples, i.e. in (100) sapphire and x-cut lithium niobate (LiNbO3). In particular, the sapphire in-plane vibrations between 350 cm−1 to 800 cm−1 that correspond to LO phonon modes along the crystal b- and c-axis are determined with a spatial resolution of < λ/10, without needing any fitting parameters. In LiNbO3, we identify the in-plane orientation of its optical axis via the phonon modes, demonstrating that our method can be applied without prior knowledge of the crystal orientation. Our method can be elegantly adapted to retrieve the in-plane anisotropic response of a broad range of materials, i.e. subwavelength microcrystals, van-der-Waals materials, or topological insulators.

Subject terms: Nanoscience and technology, Infrared spectroscopy, Optics and photonics, Infrared spectroscopy

s-SNOM is a powerful tool, but it is less sensitive to in-plane variations. Here the authors present a method to improve this with a metallic microdisk antenna, which they demonstrate by probing in-plane phonon responses.

Introduction

Scattering-type scanning near-field microscopy (s-SNOM) has emerged as a capable optical characterization tool1,2 and been widely used for probing nanoscale quantum phenomena3–9. In the recent decade, s-SNOM has demonstrated phase-resolved nano-spectroscopy at extreme sub-wavelength scales10–12, which has been applied for the identification of local vibrational fingerprints of various materials13–18, quantitative determinations of the local carrier density in semiconductors19–22, and investigations of surface polariton dispersions23–26. Light sources suitable for s-SNOM include broadband femtosecond lasers27,28, tunable gaseous or quantum cascade lasers29, thermal radiation sources30–32, free-electron lasers33–35, and synchrotron light36,37. Since its introduction, s-SNOM has been demonstrated to be less sensitive to the in-plane sample anisotropic response. This is primarily because the axisymmetric and elongated geometry of the atomic force microscope (AFM) tip shank leads to larger out-of-plane polarizability38,39. In uniaxial materials, the contributions from in-plane and out-of-plane components are described by several models40–42. Dielectric constants along these directions can be extracted with the help of waveguide modes43 or dispersive substrate44. Meanwhile, the near-field contrast arising from in-plane anisotropy has been predicted to be small for standard s-SNOM measurements45. This shortcoming not only impedes the nanoscale investigation of in-plane sample responses but also limits the anisotropic sensitivity of the near-field technique, making it, in certain cases, less desirable compared to its far-field counterparts such as ellipsometry. Enhanced in-plane near-field contrast has been realized with the second harmonic generation induced by a tilted tip46, or by probing at the proximity of strong phonon resonance frequencies34,47–51. However, these methods either require alteration of the conventional s-SNOM setup, or prior knowledge of the materials (phonon frequencies, non-zero second-order optical susceptibility, etc.), which implies difficulties for investigating new materials at a broad spectral range.

On the other hand, optical antennas are widely used in photonic devices52. An antenna can convert propagating light into the spatially confined evanescent field with specific in-plane momentum or polarization53. Optical antenna resonances have been extensively studied using s-SNOM54–56. Moreover, the concept of antenna-enhanced spectroscopy has existed for years57–60. It has also been demonstrated that antennas can enhance the contrast and sensitivity of near-field nano-spectroscopy via locally boosting the field intensity61–63. However, using antennas to selectively enhance the directional (in-plane) response of s-SNOM has not been theoretically nor experimentally demonstrated. Because of the in-plane dipolar geometry of most optical antennas, it primarily couples to the in-plane permittivity of the substrate, complementary to the typical measurement scheme of s-SNOM.

In this work, we demonstrate an easy-to-implement method for nano-spectroscopy with enhanced in-plane sensitivity, especially in-plane phonon responses, by making use of an off-resonant plasmonic disk antenna. The antenna functions as a messenger that converts the in-plane substrate dielectric response to an out-of-plane field intensity and phase contrast, which can be readily measured by s-SNOM nano-spectroscopy.

Results

Experimental schematic

As a proof-of-concept demonstration, we use s-SNOM to investigate the anisotropic in-plane phonon responses of sapphire (α-Al2O3), an extensively used substrate material for thin-film growth. This is achieved by measuring the angle-dependent plasmonic responses of a micro-sized gold disk antenna on the sapphire substrate. The shape of the antenna is chosen such that the structure remains invariant under sample rotation, which eliminates variances induced by geometric factors. The plasmon in the confined metal structure displays strong (“bright spot”) and weak (“dark spot”) field confinement at the tip–sample interface, which originates from the tip–disk interaction that captures the relative phase difference between the dipole moments of the tip and the disk64–67 (see the section “Discussion” and Supplementary Note 3 for further details). Comparing the spectra of the “bright spot” to the “dark spot” provides insight into the in-plane dielectric properties of the substrate. The advantage is that our method can, without any model fitting, determine the orientation-dependent transverse optical (TO) and longitudinal optical (LO) phonon frequencies of the substrate with a spectral accuracy down to 10 and 3 cm−1, limited by noise and spectral resolution, respectively. The downside of our method is that it requires fabricating antennas on the sample surface and sacrifices the highest achievable spatial resolution of conventional broadband s-SNOM, typically ~20 nm. In the mid-IR frequency range (8–25 μm), the spatial resolution of our method is determined by the diameter of the disk, which is demonstrated down to 1 μm in this work.

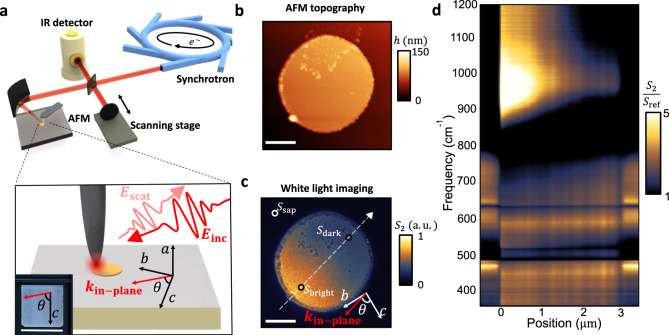

The top panel of Fig. 1a depicts the nano-spectroscopy (nano-FTIR) experimental setup in which synchrotron broadband light (Advanced Light Source at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Beamline 2.4) is coupled into a commercial s-SNOM system (Neaspec NeaSNOM) consisting of an asymmetric Michelson interferometer and an AFM. In one arm of the interferometer, the synchrotron light is focused on the apex of an AFM tip, which vibrates at its mechanical resonance frequency Ω and modulates the near-field interaction. The other arm of the interferometer consists of a moving mirror that alters the pathlength difference between the two optical paths. Demodulating the detected interference signal at higher harmonics of the tip vibration frequency (nΩ with n ≥ 2) suppresses the undesired far-field background and results in a local near-field response with a spatial resolution of ~20 nm, similar to the tip apex radius. Fourier transformation of the demodulated signal provides both amplitude and phase sensitivity due to the asymmetric Michelson interferometer setup.

Fig. 1. Experimental setup and bright–dark near-field contrast in gold disk on (100) sapphire.

a Schematics for the s-SNOM nano-spectroscopy setup and sample crystal orientation. Inset at bottom shows the photo of the sapphire wafer. The c-axis is identified by corner-cuts. The scale bar is 10 mm. b AFM topography image of the disk antenna on (100) sapphire. c The corresponding white light near-field image. kin-plane denotes the in-plane component of the incident light wavevector. Scale bars are 1 µm in both b and c. d Hyperspectral image normalized to a separate gold reference obtained by scanning the tip across the disk (indicated by the white dashed arrow in c) while collecting a spectrum at each pixel. Here A gaussian filter of small width is imposed on the hyperspectral image for reducing noise and better display without creating distortion.

Sapphire is known to exhibit strong uniaxial anisotropy in the infrared (IR) spectral range where the permittivity along the crystal c-axis is distinct from that along a- or b-axis ()68. We select (100) (m-cut) sapphire crystal as our proof-of-principle sample. A gold disk antenna of 3 μm diameter and 60 nm thickness is fabricated on the surface using standard e-beam lithography methods. The crystal orientation is schematically shown in the bottom panel of Fig. 1a. The oblique incidence of the p-polarized light leads to an in-plane wavevector component kin-plane. The angle between kin-plane and the crystal c-axis is labeled as θ, which can be gradually varied in our experiments by rotating the sample. The AFM topography of the disk antenna is shown in Fig. 1b and the spectrally integrated (“white light”) near-field amplitude image is shown in Fig. 1c. For mid-IR frequency regime, demodulation at the second harmonic 2Ω (S2) is usually sufficient to suppress the far-field background. Therefore, without specification, the near-field spectra in the rest of the article are demodulated at the second harmonic.

Bright-dark near-field contrast in micro disk antenna

The position-dependent signal intensity in the near-field image is due to the plasmonic response of the antenna and its interaction with the substrate and the tip63–65,69,70. As will be shown later, at each crystal orientation (different θ) we collect near-field amplitude and phase spectra at three important locations circled in Fig. 1c, labeled as , , , , and , , respectively. These spots are chosen because they best represent the properties of the plasmonic disk and its sapphire substrate. Near-field spectra on a separate bulk gold sample are also collected for reference and are denoted as and . In Fig. 1d we show the hyperspectral image () at to illustrate the position-dependent spectral response on and off the gold disk ( depicts the position of the tip). The spectra are obtained by a line scan parallel to from the bright side to the dark side as indicated by the white dashed arrow in Fig. 1c. The positions “0” and “3” μm mark the physical boundaries of the disk. Noticeably, the spectra on sapphire show multiple strong resonances due to the IR-active phonons below ~800 cm−1, as will be discussed in detail later. On the gold disk, unique signatures linked to the sapphire phonons are observed below ~700 cm−1. Above ~850 cm−1, a strong resonance can be observed and attributed to the geometric resonance of the disk, which occurs when the disk size matches roughly one-quarter of the wavelength. From Fig. 1d, we find that the “bright” and “dark” are relative terms specific to the frequencies. The assignment of “bright” and “dark” in the “white light” image shown in Fig. 1c is predominated by the geometric resonance of the gold disk at above ~850 cm−1.

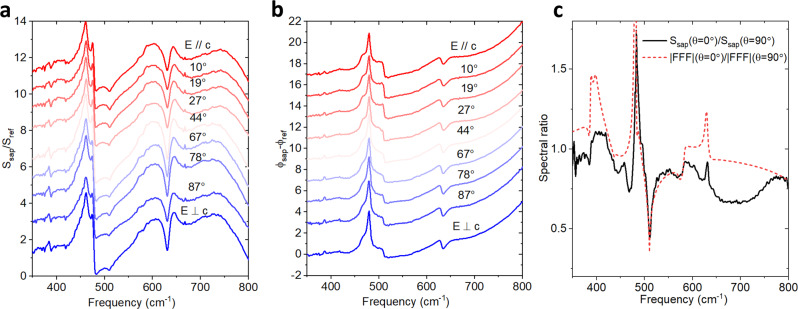

Low sensitivity to in-plane anisotropy from the bare sapphire substrate

We first verify that the intrinsic near-field signal in a conventional s-SNOM configuration is less sensitive to the sample’s in-plane anisotropy. Figure 2a and b show -dependent spectra on bare sapphire, with and at different angles from () to (), where denotes the in-plane component of the electric field in the incident light. The incident light is p-polarized and thus the in-plane component of the electric field aligns to . Our experimental accuracy of is estimated to be . Clearly, at different values, the changes are subtle, and the most prominent features are not directly related to the phonon frequencies. Moreover, since the spectra are taken on bare sapphire and then normalized to a separate gold reference sample, the multiplicative far-field factor (FFF) originating from secondary surface reflections is expected to modify the observed spectral response29,71. This -dependent FFF is approximately , where is the p-polarized Fresnel reflection coefficient. Figure 2c plots and . The qualitative consistency shows that the slight difference observed in the -dependent is largely due to the FFF instead of the intrinsic near-field response (see Supplementary Note 1 for further details).

Fig. 2. Sample orientation dependent near-field spectra on bare sapphire.

a and b θ-dependent spectra of Ssap/Sref and ϕsap−ϕref. Spectral feature (out-of-plane modes) changes at different angles are subtle. The spectra in a and b are vertically shifted for better display. c The ratio of Ssap between θ = 0° and 90° (black curve) plotted along with the ratio of FFF (far-field factor) at θ = 0° and 90° (red dashed curve).

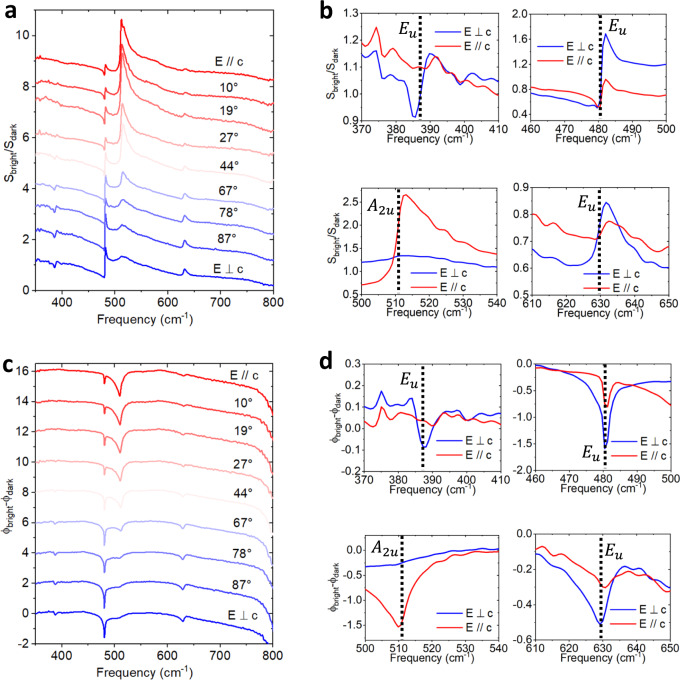

Amplitude ratio and phase difference in micro-disk antenna on sapphire

Figure 3a shows the amplitude ratio at different angles. In contrast to Fig. 2a, distinctive spectral contrast changes are observed: peaks at ~390, ~480, and ~630 cm−1 start to emerge as the in-plane electric field gradually aligns with the b-axis, while the peak at ~510 cm−1 diminishes. and are spectra taken at opposite ends of the antenna, which are ~2.5 μm apart. Such a distance is small compared to the free space wavelength (12.5–28.6 μm in this work). Thus, the FFF of two spectra can be regarded as the same, since the areas illuminated by incident light overlap almost completely in two measurements. The ratio of the spectra cancels the FFF and yields authentic near-field response. The significant peak formation/disappearance is a clear indicator of the anisotropic in-plane dielectric response, as will be detailed later. In Fig. 3b we plot the zoom-in views of at and . Interestingly, all of the spectral peaks are associated with the LO phonon frequencies of sapphire68, which are indicated by the vertical black dashed lines. More specifically, phonons (a- and b-axis phonons) can be observed when and phonons (c-axis phonons) manifest when . Notice that there is some mixture of modes that we attribute to the imperfection of alignment angle and the out-of-plane (a-axis) contribution of the substrate.

Fig. 3. Anisotropic bright–dark contrast in a 3 μm Au disk antenna on sapphire.

a -dependent spectra of . Spectral peaks emerge and disappear as rotates from to . b A zoom-in comparison of at (red) and (blue) at different frequency ranges without vertical shift. c -dependent spectra of . d A zoom-in comparison of at and at different frequency ranges without vertical shift. The black dashed lines in b and d indicate the LO phonon frequencies68. For phonons (), and . For phonons (), . The spectra in a and c are vertically shifted for better display.

Compared to the amplitude spectra, the phase spectra are even more intriguing. Significant phase contrast between different angles can be observed in Fig. 3c. In a zoom-in view (Fig. 3d), we find that the dips of are almost perfectly coincident with the LO phonon frequencies within a ±1 cm−1 range. This makes the phase contrast an even better indicator for the phonon frequencies than the peaks in the amplitude spectra, as will be explained later in the article and in Supplementary Note 2. Importantly, the phase contrast is also clearly observable on a 1 μm disk, ~20 times smaller than the wavelength (see Supplementary Note 8). However, we note that the signal-noise-ratios of spectra taken on smaller disks are worse than those on larger disks, due to weaker bright–dark contrast (see Supplementary Note 5) and weaker overall signals on smaller disks72.

Discussion

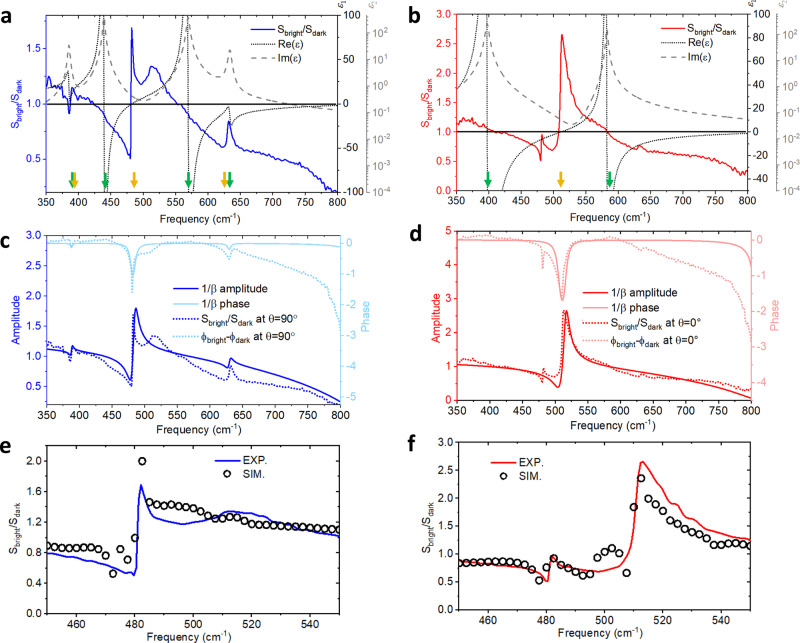

Next, we discuss the spectral features in the -dependent spectra. It is instructive to plot at () together with the b-axis (c-axis) sapphire permittivity , as shown in Fig. 4a and b). The permittivity of sapphire can be calculated by the conventional Lorentz oscillator function, which is commonly written in partial fraction decomposition form to explicitly indicate LO and TO phonon frequencies as

| 1 |

where and are the ith TO and LO phonon frequencies. and are the corresponding damping coefficients. is the high-frequency dielectric constant (parameters adapted from ref. 68). Three straightforward and important observations of the links between the spectra and the sapphire permittivity can be found: (1) the peaks in exhibit Fano-like line shape and correspond to (near LO phonon frequencies); (2) When is large (near TO phonon frequencies), 1; 3) Generally speaking when and when .

Fig. 4. Analytical modeling and simulations.

a at plotted along with the sapphire b-axis permittivity. b at plotted along with the sapphire c-axis permittivity. The green and yellow arrows in a and b indicate the and , respectively. c, d amplitudes and phases of calculated with b-axis permittivity and c-axis permittivity together with experimental data. e and f simulated spectra plotted with experimental data for and , respectively.

The observations can be understood intuitively by a straightforward antenna analysis73. When an antenna is placed at the interface of two homogenous media (i.e. air and sapphire), its response is altered by the dielectric environment. In particular, when the substrate’s permittivity is close to zero (epsilon-near-zero or ENZ), highly resonant behavior is triggered, despite the dimension and geometry of the antenna itself70,74. This resonance therefore emerges near LO phonon frequencies (marked by yellow arrows in Fig. 4a and b) and leads to strong local electric field enhancement. The high contrast between the “bright” and “dark” regions of this resonating mode can be picked up by near-field measurements. Near the TO phonon frequencies (marked by green arrows in Fig. 4a and b), the permittivity – especially the imaginary part – is large (also known as the epsilon-near-pole or ENP) and the antenna response is strongly suppressed. Therefore, at ENP, the antenna shows a spatially homogenous near-field signal, where or .

For a semi-quantitative understanding, we treat the disk-sapphire system quasi-statically and find out that contrast agrees well with the effective in-plane polarizability of the metal disk. Under static electric field , the resulting disk dipole moment is , where is the bare in-plane polarizability of the disk, is the image dipole moment, is the quasi-static reflection coefficient, is the substrate in-plane permittivity, and is the distance of the induced dipole above the substrate surface75, which is in the same order as antenna thickness. As a result, . Since scales with the volume of the disk, which is much larger than , . In Fig. 4c and d, we plot the amplitudes and phases of and , respectively. Note that to better match the experimental peak width and height, the damping rates for the LO phonon at 510.9 cm−1 and LO phonon at 481.7 cm−1 are artificially broadened from 1.1 and 1.9 cm−1 to 8.8 and 7.6 cm−1, respectively in the calculated permittivity. This broadening is justified due to the limited spectral resolution (3.3 cm−1) of the instrument and the extra damping caused by the tip–sample interaction76,77. The line shapes of both the amplitude and phase strongly resemble the experimental spectra. Particularly, the phase of peaks when , making the phase a good indicator for LO phonon frequencies (see Supplementary Note 2 for further details). The discrepancy in phase at high frequencies is due to the intrinsic geometric resonance of the disk above 850 cm−1, where the disk is similar to a quarter-wavelength antenna. This effect is not accounted for in the model.

The reason we resolve a bright–dark near-field contrast that tracks the effective disk polarizability is due to the tip–disk interaction. The tip effectively resolves the charge density distribution at the two ends of the disk67 via the relative phase difference between the dipole moments of the tip and the disk. This can be proven with numerical simulations (see Supplementary Note 3 for details) following the recently proposed simulation scheme with realistic tip modeling and signal demodulation78. To capture the major features while saving computational power, we carry out 2D FEM simulations, where a 3-μm-long antenna is placed on a sapphire substrate. The AFM tip is modeled as a truncated triangle with 20 μm height, 5 μm top radius, and 25 nm bottom radius, and the light excitation is modeled as a plane wave incident at a 60° angle with respect to the surface normal, as in the experimental setup. The permittivity tensor of sapphire used above is also applied in the simulation. In Fig. 4e and f the experimental spectra and the simulated spectra are plotted together, highlighting consistencies between them. The simulations are restricted to a 450–550 cm−1 window due to time and computational power constraints, emphasizing the Eu LO phonon at 481.7 cm−1 and the A2u LO phonon at 510.9 cm−1. Nonetheless, the phonon signatures within that window are clearly reproduced. We note that without including the tip in the simulation, a correct spectral shape cannot be obtained (see Supplementary Fig. 2 for details).

To further demonstrate the broad applicability of our method, we applied our methodology also to an x-cut lithium niobate (LiNbO3) sample and determined its c-axis orientation. LiNbO3 has wide applications in electro-optics79, nonlinear optics80, fiber-optics81, and quantum information82,83. Like sapphire, LiNbO3 exhibits uniaxial anisotropy where the permittivity along the crystal c-axis is distinctively different as compared to the a- or b-axis84. The single-crystalline wafer is double-sided polished and has a size of 10 mm × 10 mm with a 1 mm thickness. The c-axis lies in the sample plane and is oriented parallel to one of the square edges. Since there are no corner cuts that would allow us to clearly assign the c-axis to one of the in-plane directions, [see the inset of Fig. 5a] this sample constitutes an excellent test to explore the full potential and benefits of the Au-disk method here. We hence fabricated 60 nm-thick gold disks of various sizes onto that x-cut LiNbO3 sample surface and measured the bright/dark ratio with the incident electric field being oriented parallel to each side once, using the same method as for the sapphire case above. The method helped us determine the c-axis orientation.

Fig. 5. Anisotropic bright–dark contrast in Au disks with various diameters on LiNbO3.

a, b at two orthogonal sample orientations for gold disks on LiNbO3, respectively. The green arrows in a and b indicate the along b- and c-axes, respectively. The diameters of the disks are 1 μm, 3 μm, and 5 μm. is plotted in a. with is plotted in b. Inset of a shows a photo of the LiNbO3 wafer. Note there are no corner cuts to help identify the c-axis. The electric field is set to be parallel to the edges of the LiNbO3. The scale bar is 10 mm. c, d for the same disks under the same sample orientation with a and b, respectively. Yellow arrows in c and d indicate the along b- and c-axes, respectively. and phases are shown in solid curves in c and d, respectively.

Figure 5a–d show the amplitude ratio and phase difference of gold disks with diameters of 1, 3, and 5 μm on LiNbO3 with two orthogonal sample orientations. Anisotropy is observed for all disk sizes. We can infer the phonon frequencies of LiNbO3 along the two crystal orientations and hence determine its correct c-axis orientation by comparing to the literature84. The small peak between 400 and 450 cm−1 in Fig. 5a and the relative depths for dips centered at 418 and 450 cm−1 in Fig. 5c are well captured by the amplitude and phase of , respectively. For all disks, are close to 1 at , marked by green arrows in Fig. 5a. The dips of coincide with , as indicated by yellow arrows in Fig. 5c. These similarities with sapphire results show the repeatability and robustness of our method. For the case of E//c, with is applied to incorporate the out-of-plane (a-axis) contribution34. Due to higher intrinsic phonon damping of LiNbO3 than sapphire, the out-of plane contribution is more prominent, and the fitting quality is slightly worse. The change of contrast on different gold disk diameters can be attributed to finite-size effects of the disk, which may include finite in-plane scattering momentum and overlap of detected region. A detailed discussion will come in a future work.

In conclusion, the plasmonic disk antenna displays a modified resonance behavior due to the in-plane permittivity of the substrate. The antenna serves as a converter that transmits the in-plane interaction of the disk and substrate to the out-of-plane localized electric field. This is especially useful for identifying an epsilon-near-zero region, where a sharp resonance feature of the antenna can be clearly identified in real space. Therefore, LO phonon frequencies can be identified through nano-spectroscopy as a distinctive phase contrast. The methodology is particularly suitable for thick (e.g. > 10 μm) anisotropic crystals with moderate phonon resonance damping and wide separation between LO and TO phonons. Anisotropy can be easily identified by rotating the crystal axis of the sample, which is not obvious with a tip-on-bare-sample scheme. Our work is a firm step towards obtaining the full anisotropic dielectric tensor at the nanoscale. However, one important obstacle seems to lie in the fact that the electromagnetic damping by the tip or the disk cannot be quantified appropriately at this stage, which certainly calls for future investigation.

With an improved understanding and engineering of the antenna structures, we foresee interesting future studies on the anisotropic in-plane responses of a broad range of materials, especially samples with subwavelength size such as topological microcrystals. Metallic structures of different shapes and sizes can also be explored for significantly enhancing the technique sensitivity by utilizing the intrinsic geometric resonances of the antenna. Plasmonic materials or chiral molecules beyond metallic antennas could also be used to yield a finer spatial resolution or sensitivity of the photon chirality. For example, a gateable graphene disk or dipolar molecules can probably further improve the spatial resolution to about 100 nm, which is on the order of the wavelength of graphene plasmons85.

Methods

Sample preparation

Both m-cut (100) sapphire and x-cut LiNbO3 substrates are purchased from MTI Corp. The sapphire is 1-side-polished with 0.5 mm thickness, and the LiNbO3 is 2-side-polished with 1 mm thickness. Gold disks are fabricated on the polished surface by electron-beam lithography (EBL).

Nano-FTIR

Nano-FTIR is performed with a commercial scattering-type near-field microscope (Neaspec GmbH, Germany) located at beamline 2.4, Advanced Light Source (ALS), Berkeley, USA. ALS provides broadband IR radiation of high illuminance. The AFM was operated in tapping mode with ~65 nm oscillation amplitude, with cantilever resonance frequency at ~250 kHz. The Cu:Ge detector is sensitive to low-frequency IR signal down to ~330 cm−1.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Xiangdong Guo for the helpful discussions. This work is partially supported by the RISE2 node of NASA’s Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute under NASA Cooperative Agreement 80NSSC19MO2015. X.Z.C, M.K.Liu, and D.N.Basov acknowledge support from the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, National Quantum Information Science Research Centers, Co-design Center for Quantum Advantage (C2QA) under contract number DE-SC0012704. This research used resources of the Advanced Light Source, a DOE Office of Science User Facility under contract no. DE-AC02-05CH11231. Sample preparation was supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division, of the US Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05-CH11231, within the sp2-Bonded Materials Program (KC2207). Z.Y. acknowledges partial support from the ALS Doctoral Fellowship in Residence Program. L.W., L.M.E., and S.C.K. acknowledge funding by the BMBF under Grant Nos. 05K16ODA and 05K19ODB, as well as by the Würzburg-Dresden Cluster of Excellence on Complexity and Topology in Quantum Matter (ct.qmat) and by the TU Dresden graduate academy.

Author contributions

M.K.L. supervised the research and designed the experiments. W.S., Z.W., and A.Z. prepared the sample. Z.Y., S.G.C., H.A.B., and M.C.M conducted the IR experiments. X.C., S.X., Z.Z., F.L., A.S.M., M.T., W.Z., and X.C. performed the numerical simulations. Z.Y., X.C., L.W., Y.S., A.S.M., G.L.C., D.N.B., L.M.E., S.C.K., and M.K.L. performed the analytical modeling. M.K.L., Z.Y., X.C., L.W., and S.X. wrote the paper. All authors discussed and commented on the manuscript.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Gregory Wurtz and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Ziheng Yao, Xinzhong Chen.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-22844-3.

References

- 1.Hillenbrand R, Keilmann F. Complex optical constants on a subwavelength scale. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000;85:3029–3032. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.3029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keilmann F, Hillenbrand R. Near-field microscopy by elastic light scattering from a tip. Philos. Trans. A. 2004;362:787–805. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2003.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLeod AS, et al. Multi-messenger nanoprobes of hidden magnetism in a strained manganite. Nat. Mater. 2020;19:397–404. doi: 10.1038/s41563-019-0533-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sunku SS, et al. Photonic crystals for nano-light in moiré graphene superlattices. Science. 2018;362:1153–1156. doi: 10.1126/science.aau5144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Metzger B, et al. Purcell-enhanced spontaneous emission of molecular vibrations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019;123:153001. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.123.153001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen X, et al. Moiré engineering of electronic phenomena in correlated oxides. Nat. Phys. 2020;16:631–635. doi: 10.1038/s41567-020-0865-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dolado I, et al. Nanoscale guiding of infrared light with hyperbolic volume and surface polaritons in van der Waals material ribbons. Adv. Mater. 2020;32:1906530. doi: 10.1002/adma.201906530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mooshammer F, et al. Nanoscale near-field tomography of surface states on (Bi0.5Sb0.5)2Te3. Nano Lett. 2018;18:7515–7523. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b03008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taboada-Gutiérrez J, et al. Broad spectral tuning of ultra-low-loss polaritons in a van der Waals crystal by intercalation. Nat. Mater. 2020;19:964–968. doi: 10.1038/s41563-020-0665-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen X, et al. Modern scattering‐type scanning near‐field optical microscopy for advanced material research. Adv. Mater. 2019;31:1804774. doi: 10.1002/adma.201804774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bechtel HA, Muller EA, Olmon RL, Martin MC, Raschke MB. Ultrabroadband infrared nanospectroscopic imaging. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:7191–7196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400502111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khatib O, Bechtel HA, Martin MC, Raschke MB, Carr GL. Far infrared synchrotron near-field nanoimaging and nanospectroscopy. ACS Photonics. 2018;5:2773–2779. doi: 10.1021/acsphotonics.8b00565. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freitas RO, et al. Infrared nanospectroscopy at the LNLS: current status and ongoing developments. Synchrotron Radiat. News. 2017;30:24–30. doi: 10.1080/08940886.2017.1338420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muller EA, Pollard B, Bechtel HA, van Blerkom P, Raschke MB. Infrared vibrational nanocrystallography and nanoimaging. Sci. Adv. 2016;2:e1601006. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1601006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pollard B, Maia FCB, Raschke MB, Freitas RO. Infrared vibrational nanospectroscopy by self-referenced interferometry. Nano Lett. 2016;16:55–61. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dominguez G, et al. Nanoscale infrared spectroscopy as a non-destructive probe of extraterrestrial samples. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5445. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen X, et al. Ultrabroadband infrared near-field spectroscopy and imaging of local resonators in percolative gold films. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B. 2019;36:3315. doi: 10.1364/JOSAB.36.003315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisele M, et al. Ultrafast multi-terahertz nano-spectroscopy with sub-cycle temporal resolution. Nat. Photonics. 2014;8:841–845. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2014.225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacob R, et al. Quantitative determination of the charge carrier concentration of ion implanted silicon by IR-near-field spectroscopy. Opt. Express. 2010;18:26206–26213. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.026206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aghamiri NA, et al. Hyperspectral time-domain terahertz nano-imaging. Opt. Express. 2019;27:24231. doi: 10.1364/OE.27.024231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.von Ribbeck H-G, et al. Spectroscopic THz near-field microscope. Opt. Express. 2008;16:3430–3438. doi: 10.1364/OE.16.003430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jung L, et al. Quantification of carrier density gradients along axially doped silicon nanowires using infrared nanoscopy. ACS Photonics. 2019;6:1744–1754. doi: 10.1021/acsphotonics.9b00466. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dai S, et al. Tunable phonon polaritons in atomically thin van der Waals crystals of boron nitride. Science. 2014;343:1125–1129. doi: 10.1126/science.1246833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feres FH, et al. Dipole modelling for a robust description of subdiffractional polariton waves. Nanoscale. 2019;11:21218–21226. doi: 10.1039/C9NR07387F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi Z, et al. Amplitude- and phase-resolved nanospectral imaging of phonon polaritons in hexagonal boron nitride. ACS Photonics. 2015;2:790–796. doi: 10.1021/acsphotonics.5b00007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao Z, et al. Nanoimaging and nanospectroscopy of polaritons with time resolved s-SNOM. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2019;8:1901042. doi: 10.1002/adom.201901042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amarie S, Keilmann F. Broadband-infrared assessment of phonon resonance in scattering-type near-field microscopy. Phys. Rev. B - Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2011;83:045404. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.83.045404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huth F, et al. Nano-FTIR absorption spectroscopy of molecular fingerprints at 20 nm spatial resolution. Nano Lett. 2012;12:3973–3978. doi: 10.1021/nl301159v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang LM, et al. Near-field spectroscopy of silicon dioxide thin films. Phys. Rev. B. 2012;85:075419. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.85.075419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huth F, Schnell M, Wittborn J, Ocelic N, Hillenbrand R. Infrared-spectroscopic nanoimaging with a thermal source. Nat. Mater. 2011;10:352–356. doi: 10.1038/nmat3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Callahan BT, et al. Broadband infrared vibrational nano-spectroscopy using thermal blackbody radiation. Opt. Express. 2015;23:32063. doi: 10.1364/OE.23.032063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagner M, et al. Ultrabroadband nanospectroscopy with a laser-driven plasma source. ACS Photonics. 2018;5:1467–1475. doi: 10.1021/acsphotonics.7b01484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cricenti A, et al. Free-electron-laser near-field nanospectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1998;73:151–153. doi: 10.1063/1.121739. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kehr SC, et al. Anisotropy contrast in phonon-enhanced apertureless near-field microscopy using a free-electron laser. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;100:256403. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.256403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Oliveira TVAG, et al. Nanoscale-confined terahertz polaritons in a van der Waals Crystal. Adv. Mater. 2021;33:2005777. doi: 10.1002/adma.202005777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hermann P, et al. Near-field imaging and nano-Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy using broadband synchrotron radiation. Opt. Express. 2013;21:2913–2919. doi: 10.1364/OE.21.002913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freitas RO, et al. Low-aberration beamline optics for synchrotron infrared nanospectroscopy. Opt. Express. 2018;26:11238. doi: 10.1364/OE.26.011238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim D-S, Kim ZH. Role of in-plane polarizability of the tip in scattering near-field microscopy of a plasmonic nanoparticle. Opt. Express. 2012;20:8689. doi: 10.1364/OE.20.008689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schnell M, Garcia-Etxarri A, Alkorta J, Aizpurua J, Hillenbrand R. Phase-resolved mapping of the near-field vector and polarization state in nanoscale antenna gaps. Nano Lett. 2010;10:3524–3528. doi: 10.1021/nl101693a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cvitkovic A, Ocelic N, Hillenbrand R. Analytical model for quantitative prediction of material contrasts in scattering-type near-field optical microscopy. Opt. Express. 2007;15:8550. doi: 10.1364/OE.15.008550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang B-Y, Zhang LM, Castro Neto AH, Basov DN, Fogler MM. Generalized spectral method for near-field optical microscopy. J. Appl. Phys. 2016;119:054305. doi: 10.1063/1.4941343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McLeod AS, et al. Model for quantitative tip-enhanced spectroscopy and the extraction of nanoscale-resolved optical constants. Phys. Rev. B. 2014;90:085136. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.90.085136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu, D., Yang, X., Li, C. et al. Probing optical anisotropy of nanometer-thin van der waals microcrystals by near-field imaging. Nat. Commun.8, 1471 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Ruta FL, Sternbach AJ, Dieng AB, McLeod AS, Basov DN. Quantitative nanoinfrared spectroscopy of anisotropic van der Waals materials. Nano Lett. 2020;20:7933–7940. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c02671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schneider SC, Grafström S, Eng LM. Scattering near-field optical microscopy of optically anisotropic systems. Phys. Rev. B. 2005;71:115418. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.71.115418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park KD, Raschke MB. Polarization control with plasmonic antenna tips: a universal approach to optical nanocrystallography and vector-field imaging. Nano Lett. 2018;18:2912–2917. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b00108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schneider S, et al. Impact of optical in-plane anisotropy on near-field phonon polariton spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007;90:10–13. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wehmeier L, et al. Polarization-dependent near-field phonon nanoscopy of oxides: SrTiO3, LiNbO3, and PbZr0.2Ti0.8O3. Phys. Rev. B. 2019;100:47–52. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.100.035444. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wehmeier L, et al. Phonon-induced near-field resonances in multiferroic BiFeO3 thin films at infrared and THz wavelengths. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2020;116:071103. doi: 10.1063/1.5133116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Döring J, et al. Low-temperature nanospectroscopy of the structural ferroelectric phases in single-crystalline barium titanate. Nanoscale. 2018;10:18074–18079. doi: 10.1039/C8NR04081H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aminpour H, Eng LM, Kehr SC. Spatially confined vector fields at material-induced resonances in near-field-coupled systems. Opt. Express. 2020;28:32316. doi: 10.1364/OE.402893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bharadwaj P, Deutsch B, Novotny L. Optical antennas. Adv. Opt. Photonics. 2009;1:438–483. doi: 10.1364/AOP.1.000438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Novotny L, van Hulst N. Antennas for light. Nat. Photonics. 2011;5:83–90. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2010.237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schnell M, et al. Real-space mapping of the chiral near-field distributions in spiral antennas and planar metasurfaces. Nano Lett. 2016;16:663–670. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b04416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grefe SE, et al. Near-field spatial mapping of strongly interacting multiple plasmonic infrared antennas. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013;15:18944. doi: 10.1039/c3cp53104j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Olmon RL, Krenz PM, Jones AC, Boreman GD, Raschke MB. Near-field imaging of optical antenna modes in the mid-infrared. Opt. Express. 2008;16:20295. doi: 10.1364/OE.16.020295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abb M, Wang Y, Papasimakis N, de Groot CH, Muskens OL. Surface-enhanced infrared spectroscopy using metal oxide plasmonic antenna arrays. Nano Lett. 2014;14:346–352. doi: 10.1021/nl404115g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aksu S, Cetin AE, Adato R, Altug H. Plasmonically enhanced vibrational biospectroscopy using low-cost infrared antenna arrays by nanostencil lithography. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2013;1:798–803. doi: 10.1002/adom.201300133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schumacher, T., Kratzer, K., Molnar, D. et al. Nanoantenna-enhanced ultrafast nonlinear spectroscopy of a single gold nanoparticle. Nat. Commun. 2, 333 (2011).

- 60.Xu H, Bjerneld EJ, Käll M, Börjesson L. Spectroscopy of single hemoglobin molecules by surface enhanced Raman scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999;83:4357–4360. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.4357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mattis Hoffmann J, Hauer B, Taubner T. Antenna-enhanced infrared near-field nanospectroscopy of a polymer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012;101:193105. doi: 10.1063/1.4766178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Luan Y, McDermott L, Hu F, Fei Z. Tip- and plasmon-enhanced infrared nanoscopy for ultrasensitive molecular characterizations. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2020;13:034020. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevApplied.13.034020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Muller EA, et al. Nanoimaging and control of molecular vibrations through electromagnetically induced scattering reaching the strong coupling regime. ACS Photonics. 2018;5:3594–3600. doi: 10.1021/acsphotonics.8b00425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.García-Etxarri A, Romero I, García de Abajo FJ, Hillenbrand R, Aizpurua J. Influence of the tip in near-field imaging of nanoparticle plasmonic modes: Weak and strong coupling regimes. Phys. Rev. B. 2009;79:125439. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.79.125439. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen X, et al. Rigorous numerical modeling of scattering-type scanning near-field optical microscopy and spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017;111:223110. doi: 10.1063/1.5008663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Walla F, et al. Near-field observation of guided-mode resonances on a metasurface via dielectric nanosphere excitation. ACS Photonics. 2018;5:4238–4243. doi: 10.1021/acsphotonics.8b00900. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chui ST, et al. Photo-induced charge density distribution in metal surfaces and its extraction with apertureless near-field optics. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2019;31:24LT01. doi: 10.1088/1361-648X/ab0fb3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schubert M, Tiwald TE, Herzinger CM. Infrared dielectric anisotropy and phonon modes of sapphire. Phys. Rev. B. 2000;61:8187–8201. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.61.8187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chui ST, Chen X, Liu M, Lin Z, Zi J. Scattering of electromagnetic waves from a cone with conformal mapping: application to scanning near-field optical microscope. Phys. Rev. B. 2018;97:081406. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.97.081406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim J, et al. Role of epsilon-near-zero substrates in the optical response of plasmonic antennas. Optica. 2016;3:339. doi: 10.1364/OPTICA.3.000339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Autore M, Mester L, Goikoetxea M, Hillenbrand R. Substrate matters: surface-polariton enhanced infrared nanospectroscopy of molecular vibrations. Nano Lett. 2019;19:8066–8073. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b03257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen X, et al. THz near-field imaging of extreme subwavelength metal structures. ACS Photonics. 2020;7:687–694. doi: 10.1021/acsphotonics.9b01534. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Agio, M. & Alù, A. Optical Antennas. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy Vol. 58 (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

- 74.Schulz SA, et al. Optical response of dipole antennas on an epsilon-near-zero substrate. Phys. Rev. A. 2016;93:063846. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevA.93.063846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Knoll B, Keilmann F. Enhanced dielectric contrast in scattering-type scanning near-field optical microscopy. Opt. Commun. 2000;182:321–328. doi: 10.1016/S0030-4018(00)00826-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schmidt P, et al. Nano-imaging of intersubband transitions in van der Waals quantum wells. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018;13:1035–1041. doi: 10.1038/s41565-018-0233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang, H., Wang, L., Jakob, D. S. & Xu, X. G. Tomographic and multimodal scattering-type scanning near-field optical microscopy with peak force tapping mode. Nat. Commun. 9, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Mooshammer F, et al. Quantifying nanoscale electromagnetic fields in near-field microscopy by Fourier demodulation analysis. ACS Photonics. 2020;7:344–351. doi: 10.1021/acsphotonics.9b01533. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Guarino A, Poberaj G, Rezzonico D, Degl’Innocenti R, Günter P. Electro-optically tunable microring resonators in lithium niobate. Nat. Photonics. 2007;1:407–410. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2007.93. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Broderick NGR, Ross GW, Offerhaus HL, Richardson DJ, Hanna DC. Hexagonally poled lithium niobate: a two-dimensional nonlinear photonic crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000;84:4345–4348. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.4345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wooten EL, et al. Review of lithium niobate modulators for fiber-optic communications systems. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2000;6:69–82. doi: 10.1109/2944.826874. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jin H, et al. On-chip generation and manipulation of entangled photons based on reconfigurable lithium-niobate waveguide circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014;113:103601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.103601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Förtsch M, et al. A versatile source of single photons for quantum information processing. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1–5. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Barker AS, Loudon R. Dielectric properties and optical phonons in LiNbO3. Phys. Rev. 1967;158:433–445. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.158.433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fei Z, et al. Gate-tuning of graphene plasmons revealed by infrared nano-imaging. Nature. 2012;487:82–85. doi: 10.1038/nature11253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.