Abstract

Objective:

To develop a conceptual theory to describe how financial strain affects women with young children to inform clinical care and research.

Design:

Qualitative, grounded theory.

Setting:

Participants were recruited from the waiting area of a pediatric clinic and an office of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children embedded within the largest safety-net academic medical center in New England. Participants were interviewed privately at the medical center or in the community.

Participants:

Twenty-six English-speaking women, mostly single and African American/Black, with at least one child 5 years old or younger, were sampled until thematic saturation was met.

Methods:

We used grounded theory methodology to conduct in-depth, semistructured interviews with participants who indicated that they experienced financial strain. We analyzed the interview data using constant comparative analysis, revised the interview guide based on emerging themes, and developed a theoretical model.

Results:

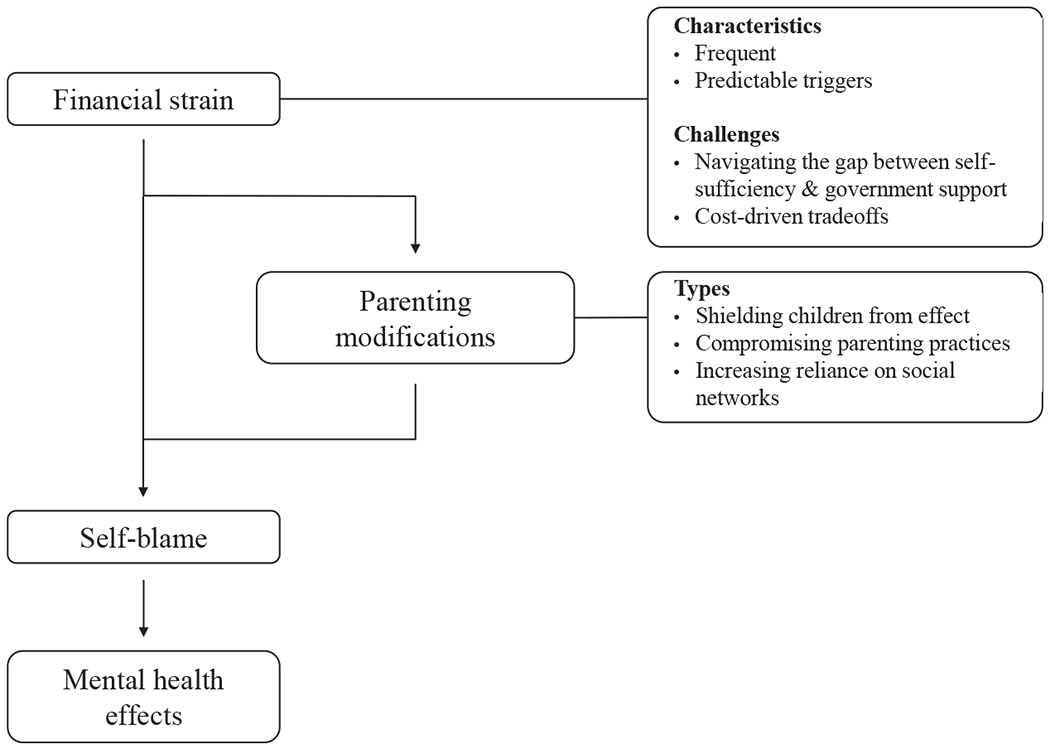

Five interrelated themes emerged and were developed into a theoretical model: Financial Strain Has Specific Characteristics and Common Triggers, Financial Strain Is Exacerbated by Inadequate Assistance and Results in Tradeoffs, Financial Strain Forces Parenting Modifications, Women Experience Self-Blame, and Women Experience Mental Health Effects.

Conclusion:

For women with young children, financial strain results in forced tradeoffs, compromised parenting practices, and self-blame, which contribute to significant mental health problems. These findings can inform woman-centered clinical practice and advocacy interventions. Women’s health care providers should identify families experiencing financial strain, provide referrals to financial services, and join advocacy efforts to advance social policies that address the structural causes of poverty, such as increased minimum wage and paid family leave.

Keywords: grounded theory, maternal health, parenting, pregnancy, safety-net providers

“Financial strain” is defined as a specific stress that arises from economic challenges, including financial insecurity, high debt, and poor credit. Whereas poverty is linked specifically to income level, financial strain is a subjective emotional state that is not linked to a specific income (Lyons et al., 2019). Financial strain has a known detrimental effect on women’s health during pregnancy independent of the effect of poverty (Frank et al., 2014; Shippee et al., 2012). Poverty is also associated with negative changes in maternal and child physical and mental health and child development (Beck et al., 2018; Wickham et al., 2017). Financial strain may uniquely affect women with young children and has implications for maternal and child health outcomes. In the United States, one in eight women lives in poverty (<100% of Federal Poverty Level), and women are 38% more likely than men to live in poverty (Damaske et al., 2017; Patrick, 2017). Pregnancy and childbirth deepen this inequity. Only 57% of women with children younger than 1 year old are in the workforce compared with 74% of those with children ages 6 to 17 years (U.S. Department of Labor, 2018). Among the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development countries, the United States ranks 17 of 22 with respect to women’s labor force participation; this low ranking has been associated with a deficit of supportive workforce and child care policies in the United States (Blau & Kahn, 2013). More than one third of single women with children live in poverty (Patrick, 2017).

Little is known about women’s conceptualizations of financial strain and its effects on women with young children.

Poverty and financial strain are associated with negative effects on maternal mental health (Dijkstra-Kersten et al., 2015; Wickham et al., 2017). For instance, researchers found that mothers with financial strain had more symptoms of depression (Lange et al., 2017), whereas researchers in other quantitative studies found that symptoms of depression were mediated by factors such as attitudes toward government assistance programs (Bergmans et al., 2018) and employment status (Bourke-Taylor et al., 2011). However, the mechanisms by which financial strain affects negative maternal mental health have not been rigorously studied (Luca et al., 2020; Simon et al., 2018). Understanding how women conceptualize financial strain and how it affects them and their families is crucial to understanding the link between financial strain and mental health and developing woman-centered interventions. Specifically, qualitative analyses of women’s conceptualizations of financial strain and its effects could complement extant quantitative research on the interaction of financial strain and mental health.

Expert women’s health councils have recently called for a focus on mental health to decrease rates of maternal morbidity and mortality (Kendig et al., 2017; Walker et al., 2019). The National Partnership for Maternal Safety has developed consensus bundles on evidence-based practices, and a recent bundle focused on addressing mental health to reduce peripartum racial and ethnic disparities (Howell et al., 2018). The bundle incudes recommendations for universal screening for depression and systematic response protocols for positive screening results, including referrals for therapy and/or medication (Howell et al., 2018). However, given the association between financial strain and mental health, an opportunity exists to examine whether clinical and policy interventions to alleviate financial strain could improve maternal mental health outcomes (Wahlbeck et al., 2017).

Midwifery, obstetrics and gynecology, family medicine, and pediatrics settings have significant potential for providers to identify and support women who struggle with financial strain. Multiple professional organizations whose members care for women and children, such as the Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric, and Neonatal Nurses (Lathrop, 2020); the American College of Nurse-Midwives (2018); the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (Sufrin et al., 2018); the American Academy of Pediatrics (2016); and the American Academy of Family Physicians (Czapp & Kovach, 2015), have called for providers to address social determinants of health during clinical care to achieve health equity in outcomes. Murray (2018) advocated for a Health in All Policies approach in nursing to include health in all social policies to buffer individuals from the effects of social determinants of health. In light of this background, we sought to develop a conceptual theory to describe how financial strain affects women with young children to inform clinical care and research.

Methods

Design

We used a grounded theory design (Birks & Mills, 2015; Glaser & Strauss, 1967) because this inductive methodology is well suited to develop a deeper understanding of the pathway by which financial strain affects women with young children in the context of poverty and low income. Grounded theory methodology starts with a broad question and allows for participants to guide the direction of the research, which is important for complex psychosocial phenomena. The institutional review board at Boston University Medical Campus reviewed and approved the study.

Setting

To recruit participants, we hung fliers in the waiting areas of a pediatric clinic and an office of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). Both of these settings are affiliated with an academic medical center that serves a predominantly low-income, racially diverse patient population in New England. When interested women contacted the study team, we screened them by phone for eligibility and initial consent. Interviews took place in person in a mutually convenient, private location in the outpatient offices or community.

Sample

We used purposive sampling (Coyne, 1997) to recruit women from July 2017 to September 2018. Women were eligible to participate if they indicated that they experienced financial strain, spoke English, and had at least one child age 5 years or younger. They were also required to use the affiliated medical center for their health care or their children’s health care. There were no other exclusion criteria. We continued recruitment until we achieved thematic saturation.

Procedures

Women were recruited via fliers in the clinic and the WIC office that asked, “Have you experienced financial stress?” The fliers stated that we were recruiting women with children from birth to 5 years old to interview about this strain, that participants would receive a $30 gift card for their time, and that the interview would take 60 to 90 minutes. The flier included the study phone number. When interested women called, the research assistant who conducted the phone screening reaffirmed that this was a study about how women with children experience financial strain and asked if they would be willing to have private interviews about financial strain in their lives. The research assistant also confirmed that the interested women were comfortable speaking English and that they had at least one child in the target age range. No income criteria were used to determine eligibility. The research assistant scheduled in-person interviews.

During the in-person interview, participants first provided written, informed consent. Next, they filled out a demographic questionnaire on a computer tablet in a secure software program and completed individual verbal interviews about their conceptualizations of financial strain, which were audiorecorded. We purposefully explored women’s conceptualizations of financial strain without providing a definition of this term, because our goal was to understand the women’s unbiased perspectives.

The research team met to review emergent themes iteratively throughout the study, in keeping with grounded theory methodology (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1990). We used constant comparative analysis to code each interview after it was transcribed. The team met every three to five interviews to determine whether the interview guide should be revised based on emerging themes. We removed questions when thematic saturation was reached (i.e., interviews yielded repetitive information for multiple participants). We added questions to explore new themes that emerged from the interviews (Coyne, 1997). Recruitment continued until thematic saturation was achieved as determined by regular review of data and triangulation meetings. Interviews were conducted by four female authors who identify as White, Latina, and Asian: L.E.M. (MD, MPH, pediatric urban health fellow), D.H. (BA, graduate student in international affairs), K.E.S., (BS, research assistant), and S.S. (undergraduate, research assistant). We include our self-identified racial/ethnic identities, training, and positions to be transparent about our lived experiences, which unavoidably influence the research process, including power dynamics with participants, despite our attention to self-reflexivity. These interviewers were trained and supervised in qualitative research methods by senior members of the research team (C.D.M. and C.J.K.).

Measures

We designed a semistructured interview guide. We used a social ecological framework to group interview questions into individual-, family-, and community-oriented sections focused on women’s conceptualization of financial strain and its effects on them, their families, and their communities and their ideas about ways to mitigate these consequences of financial strain (see Supplemental Table S1). Supplemental Table S1 represents the total of all interview questions asked and probes used in the seven different versions of the interview guide, which was iteratively revised based on emerging themes from interviews; no participant was asked all of these questions. These questions were designed to elicit participants’ perspectives and functioned as a guide rather than a checklist. We also administered a questionnaire to ask 13 demographic questions, including how participants were connected to the affiliated medical center (their own care, their child’s or children’s care), age, child’s or children’s ages and sex, number and ages of household occupants, marital status, ethnicity, race, and household income. We asked participants whether they previously used a free tax-filing service in the medical center to understand if they had used an available clinical service designed to help alleviate financial strain.

Analysis

Interviews were audiorecorded and professionally transcribed verbatim by an outside service. We verified transcriptions for accuracy by listening to the audiorecording during the first review of the transcription. We used grounded theory to allow for inductive analysis of interviews using the constant comparative approach to develop a theoretical model for the effects of financial strain on women with young children (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1990). The team included researchers with expertise in maternal-child health (L.E.M., J.I.C., H.-A.T.N., K.K., M.K.H., C.D.M., and C.J.K.), financial strain (L.E.M., M.K.H.), and prevention of depression (C.J.K.). Researchers L.E.M., J.I.C., K.E.S., and C.J.K. discussed the first five interviews to identify salient content that related to perceived financial strain and its effects on health and parenting. We used reflexivity and member reflections to ensure we conducted high-quality data analysis that incorporated and acknowledged our own biases, experiences, and conceptualizations of financial strain as we conducted the analysis (Tracy, 2010). We then used open coding and memoing to organize content and generate a codebook. Codebook development was iterative and involved defining codes and identifying illustrative quotations across the first five interviews. The codebook was imported into NVivo (Version 11); two researchers (L.E.M. and J.I.C.) coded all interviews in parallel. We conducted periodic review of coding. The team came together to review codes and discuss emergent themes every three to five interviews. Differences were resolved through consensus (L.E.M., J.I.C., and C.J.K.).

We tagged emerging themes from the coding process. During analysis, we held two triangulation meetings with experts in maternal-child health and social determinants of health (H.-A.T.N., K.K., M.K.H., C.D.M., and C.J.K.). We discussed and organized emerging categories and themes to capture key aspects of participants’ experiences with financial strain. We used axial and then selective coding and diagrams to iteratively identify themes among categories and develop a theoretical model (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Interviews continued until we achieved thematic saturation. We validated our model during three final interviews with new participants for feedback on the categories, themes, and the theoretical model. Demographic data were entered into a secured electronic database and analyzed with the use of descriptive statistics (Harris et al., 2009).

Results

Sample

We interviewed 26 participants with a mean age of 31.5 years (range, 24–41 years) and an average of two children (range, 1–5 years), including at least one child age 5 years or younger. Most (n = 19, 73%) self-identified as African American/Black, and 18 (69%) were single. Annual gross income ranged from $0 to $55,000 (median, $16,020; interquartile range, $10,469–$29,610; see Table 1). Five interrelated themes and related categories emerged (see Table 2).

Among participants, financial strain often led to forced tradeoffs, compromised parenting practices, and self-blame, which resulted in adverse mental health effects.

Table 1:

Participant Demographics (N = 26)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (range) | 31.5 (24–41) |

| Number of children, mean (range) | 2.2 (1–5) |

| Age of children, mean (range) | 6 years (7 weeks to 25 years) |

| Annual income, median (interquartile range) | $16,020 ($10,469–$29,610) |

| Race, n | |

| African American/Black | 19 |

| White | 2 |

| Asian | 1 |

| Other | 4 |

| Ethnicity, n | |

| Hispanic or Latino/a | 4 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino/a | 22 |

| Marital status, n | |

| Single (living without partner) | 18 |

| Married | 5 |

| Divorced | 1 |

| Living as a couple | 2 |

| Highest level of education completed, n | |

| Did not complete high school | 2 |

| High school graduate or high school equivalency | 9 |

| Some college or technical school | 7 |

| College degree or higher | 8 |

| Employment, n | |

| Health care (RN, CNA, lactation consultant) | 3 |

| Administrative (assistant, coordinator) | 6 |

| Teaching (substitute, crafts) | 2 |

| Sales (retail, cashier) | 4 |

| Miscellaneous (cleaner, odd jobs, food prep) | 3 |

| Student (including part-time) | 3 |

| Unemployed | 5 |

Note. CNA = certified nursing assistant; RN = registered nurse.

Table 2:

Common Themes in Participants’ Experiences of Financial Strain

| Theme | Categories |

|---|---|

| Financial Strain Has Specific Characteristics and Common Triggers | • Financial strain is frequent • Common triggers include (a) unexpected expenses, (b) loss of expected supports, and (c) predictable events such as pregnancy |

| Financial Strain Is Exacerbated by Inadequate Assistance and Results in Tradeoffs | • Inadequate resources • Self-sacrifice • Loss of resources with work |

| Financial Strain Forces Parenting Modifications | • Shielding children from financial strain; (a) attempts and (b) failures • Compromising parenting from an imagined ideal: (a) loss of presence and (b) loss of consistency • Reliance on social networks |

| Women Experience Self-Blame | • Feelings of self-responsibility • Experiencing self-blame • Feeling should be able fix the problem |

| Women Experience Mental Health Effects | • Financial strain leads to mental health effects • Self-blame exacerbates mental health problems |

Grounded Theory Model

We developed a model based on our key thematic findings that financial strain has specific characteristics and common triggers, including pregnancy; is exacerbated by inadequate assistance and resultant tradeoffs; and forces parenting modifications. The financial strain itself and the parenting modifications caused women to feel self-blame and mental health effects. We built these themes and the interactions between them into an explanatory model to describe the effects of financial strain on parenting and maternal mental health (see Figure 1). We explain the themes in greater detail in the following sections.

Figure 1.

Explanatory model: effect of financial strain on women’s parenting and mental health.

Financial Strain Has Specific Characteristics and Common Triggers

Participants described specific characteristics and triggers of financial strain in their lives, and we incorporated these into our theoretical model (see Figure 1). They described financial strain as frequent. One stated, “Every day is financially stressful.” Another elaborated:

I’m financially struggling every week, every time that I get paid. Even though I’m [at work] every single day, financially with me paying my rent, my car bill, and other bills. And now that I do have an older child that’s in college, it is even more stressful. So every week I’m just struggling to make ends meet.

Participants identified common triggers that exacerbated financial strain, including unplanned expenses. When describing a financially stressful time, one participant talked about her car breaking down; costs spiraled into the thousands, and she struggled to afford to commute to work. Loss of expected supports, such as incarceration of a partner, also precipitated financial strain. One participant explained that after her partner’s incarceration, she struggled with twice as many bills. Pregnancy was associated with financial strain, and challenges particular to pregnancy and childbirth included unpaid leave and physical and logistic difficulties encountered with working before and after the birth:

I didn’t qualify for maternity [leave], so they just gave me two months off. Eight weeks with no pay. … I’m trying to balance all my bills, and I try to work it out before by working, but my pregnancy didn’t really allow me to put in the hours.

Financial Strain Is Exacerbated by Inadequate Assistance and Results in Tradeoffs

Participants identified challenges that exacerbated financial strain, as illustrated in our theoretical model (see Figure 1). Participants faced cost-driven tradeoffs as their combined income and resources from assistance programs (e.g., Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program [SNAP], WIC, and housing subsidies) were not enough to meet their families’ basic needs:

I got the WIC. I got the food stamps now. I got the cash money for the stamps, but it’s still not enough. It’s only $119 dollars, and it’s still not enough. Nobody knows how much diapers and wipes and stuff cost. It’s crazy. I always used to tell people, “I can do this.” But this is hard.

These tradeoffs meant that participants sacrificed and even went without food to meet the needs of their children:

I barely eat, and if I do, it’s like a bowl of cereal at nighttime, and it’s just because I’m dizzy. I have to make sure they have their formula, they have their baby food, and they have clothes because they are growing like leaves … when it comes down to me, it doesn’t really matter.

Participants described the strain of losing resources from assistance programs after they increased their income when they worked more hours or received raises: “When you start making a little bit, they cut you off. So now you’re still stuck where you were before.”

Financial Strain Forces Parenting Modifications

Participants described parenting modifications that arose directly from financial strain (see Figure 1). They attempted to shield their children from being aware of financial strain, because they believed children should not worry about money. One spoke about using social services agencies at Christmas to obtain gifts and create an aura of plenty to hide her financial problems from her children. Participants wanted to protect children from a sense of deprivation but often realized their children were aware of the financial strain:

See me open a letter and find out I’ve got an overdraft. I thought I had enough. I’m talking to myself and my daughter comes out and goes, “Mommy, I got five dollars.” You know? “That’s your five dollars.” They do notice.

Participants also described that they consciously compromised their parenting practices in response to their financial strain. Some felt financial strain prevented them from engaging with their children as much as they wanted to because they were distracted or obligated to focus on their financial problems:

I was a lot more involved in the activities related to financial security during maternity leave. I felt like during that time, even though I spent plenty of time with my kid, I breastfeed so I’m always there with her, but I just feel like this took away from me the moments that I could have spent with her. I just feel like I missed out.

Participants also associated financial strain with a loss of consistency in their children’s lives with respect to discipline and routines. One spoke of her attempts to use a positive discipline system with rewards for good behavior but was unable to follow through on the rewards. Other participants described how financial strain prevented them from being the role models they aspired to be for their children; for example, one participant wished she had the resources to cook at home for her children. Finally, participants described that financial strain increased their need to rely on social networks for financial and emotional support. Many had informal systems of support within their families that provided assistance during times of financial strain.

Women Experience Self-Blame

As our model indicates, women’s self-blame arose directly from financial strain and from the parenting modifications they made because of financial strain (see Figure 1). Participants felt personally responsible for their financial problems and for their parenting modifications. They identified that decisions they made triggered financial strain:

If I just didn’t have a baby, I wouldn’t be here right now. … I don’t wanna regret my kids, I love my kids, so then it’s like, “Nope. You gotta do what you have to do because you brought them here.” That pity party doesn’t last too long.

Because of feelings of personal responsibility, participants resisted using assistance programs and blamed themselves for their inability to resolve financial problems. Some reflected on past decisions, such as childbearing, that they felt contributed to their financial problems: “I blame myself because I have all these kids.”

They also reflected on ways they hoped to parent but could not because of their financial strain and felt stressed that they did not meet these internal ideals. For example, one participant shared that she eliminated eating out once a month, the one treat she allowed the family, to deal with bills. She baked cakes at home to “make it better,” but this approach created stress for her. Finally, participants felt they should be able to create a way to escape their financial strain and blamed themselves when they could not:

I was saving to buy a car, which I actually did do a few weeks prior to having my son, but I don’t think that was a smart idea right now ‘cause I’m making payments and it’s like maybe you should cut down your… payments while you was off these two months. It’s too much right now. Maybe I didn’t plan good enough.

Women Experience Mental Health Effects

Finally, our model reflects participants’ descriptions of the effects of self-blame. They identified that self-blame led to negative mental health effects (see Figure 1). Participants endorsed significant mental health effects from the self-blame they felt that arose from their financial strain. These effects ranged from suicidality—“It stresses me out. I called the suicide hotline last night”—to anxiety and depression. Another participant described the effect of financial strain on her mental health:

It made me lose a lot of weight. I wasn’t eating that good. I ended up enrolling myself into therapy. I needed professional help, just someone to tell me that I’m not crazy the stuff that I’m going through.

Participants described that they felt at fault for their financial strain and their parenting modifications and stated that these feelings of self-blame exacerbated their mental health problems:

I get depressed kind of. … I wouldn’t go out and do things and I would kind of just hide out in my house. And I have a hard time reaching out for help when things get like that because I look at me reaching out for help as a sign of weakness and failure, so I’d rather just try and figure it out on my own. … I understand that, I can change this. … But like I felt like a failure. I felt like I was undeserving of [my kids] and their love and that I failed them and they deserved better and more. I think the stress of not being able to make sure they had everything they needed, maybe [I was] not as present as I should have been.

Discussion

In this qualitative study, we aimed to develop a theory that represents conceptualizations of financial strain among women with young children. We found financial strain often led to forced tradeoffs, compromised parenting practices, and self-blame, which ultimately resulted in adverse mental health effects. Notably, participants were acutely aware of the changes they made to their parenting because of financial strain and blamed themselves for needing to make these changes. They indicated that the experiences of financial strain and self-blame contributed to significant mental health problems that ranged from depression and anxiety to suicidality. This finding highlights financial strain as a specific, modifiable risk factor for adverse mental health that could be addressed in midwifery, obstetrics and gynecology, family medicine, and pediatrics settings. Although the relationship between financial strain and poor mental health is well described in the quantitative literature, a need exists for a deeper theoretical understanding of this relationship. Our qualitative findings illuminate the complex factors that mediate the relationship between financial strain and poor mental health, including women’s internal and external strategies for coping with financial strain. For example, women have specific ideas about how they want to parent but make conscious tradeoffs in their behavior and blame themselves for their financial strain. This finding implies that supportive, affirming interventions may be more effective than those aimed at teaching women how to parent or how to manage their finances. It also implies that helping women stabilize their finances may be therapeutic to their mental health. These findings should inform clinical practice, clinical advocacy, and policy work.

Implications

In clinical practice, a plausible implication of our theoretical model is that for women who experience the mental health effects of financial strain, financial interventions may be of clinical therapeutic value. Notably, our finding that pregnancy is a specific trigger of financial strain highlights a particularly vulnerable period during which women have frequent contact with the health care system. Thus, pregnancy-related health visits could be prime opportunities to intervene. Our findings additionally add a qualitative understanding of women’s conceptualizations of how financial strain affects their parenting. During the vulnerable pre-, peri-, and postnatal periods, clinicians could provide emotional support to minimize self-blame and acknowledge women’s ideal parenting practices and forced tradeoffs. Clinicians could use our model to think holistically about approaches to improve family functioning.

Our findings are consistent with those of previous studies in which researchers found that financial strain and poverty negatively affected women’s mental and physical health (Luca et al., 2019; Shippee et al., 2012; Wickham et al., 2017) and build on the Family Stress Model, first described by Conger and Conger (2002). In the Family Stress Model, economic hardship leads to parental distress, which leads to parental relationship problems and disrupted parenting; the ultimate outcome is child adjustment problems (Conger & Conger, 2002). This model has been validated in multiple settings with a range of child ages, health conditions, and cultural settings (Masarik & Conger, 2017).

However, this model is based on quantitative data and does not explain why parents feel distress or experience disrupted parenting. By incorporating women’s own conceptualizations, our qualitative model suggests that maternal distress arises from economic hardship and from the changes women make to their parenting. Our data also suggest that disrupted parenting is not a passive outcome that arises solely from parental distress but also from conscious choices women make to cope with economic hardship and to shield their children from it. Lange et al. (2017) similarly found that women who experienced poverty reported that they did not parent the way they wanted to; however, they did not explore women’s understanding of why they made these parenting changes or of how these parenting changes affected themselves. Our findings imply that to effectively apply the Family Stress Model, practitioners must acknowledge why parents make parenting changes and help them feel more empowered in their parenting.

Our findings underscore the extent to which women blame themselves for financial strain despite substantial systemic factors, including structural racism, that are known to exacerbate poverty and financial strain in the United States (Bailey et al., 2017; Desmond, 2016; McKernan et al., 2013; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, 2019). This context is particularly salient because most (n = 19, 73%) of our participants identified as African American/Black. Self-blame is common in individuals with mental and physical illnesses (Beverly et al., 2012; Heerink et al., 2019; Tong et al., 2015). Although not studied with respect to mental health, patients’ self-blame and perception of blame from providers with respect to physical health conditions were barriers to an effective relationship with their providers (Beverly et al., 2012; Heerink et al., 2019). Within a “first do no harm” framework, health care providers and systems must be careful to not perpetuate this self-blame sentiment that lays sole responsibility for improving life circumstances on the individual; instead, they should acknowledge the historical context of the structural racism and oppression that has led to financial strain for many families. Our findings additionally highlight pregnancy and childrearing as contributing factors to financial strain and show women’s attempts to resolve this financial strain through their parenting practices. By elevating women’s own voices and exploring their explanations of how they experience financial strain and its effects, these findings can empower clinicians to advocate for and with women and to help them reframe their experiences to avoid self-blame.

Finally, our findings have policy implications. Our participants described surviving with inadequate resources despite the combination of their income and government assistance programs. Furthermore, they felt trapped when they lost of the support from assistance programs after their incomes rose. This description reaffirms the existence of the well-described cliff effect, the abrupt point at which families are no longer eligible for government resources such as food stamps, child care subsidies, or the Earned Income Tax Credit (Albelda & Carr, 2017; Roll & East, 2014). We found that not only do women grapple with practical tradeoffs because of the cliff effect, but they also exert substantial psychological energy as they navigate these tradeoffs and modify their parenting as a result. Our findings strengthen the call to use policy interventions to improve maternal mental health outcomes (Wahlbeck et al., 2017). A powerful opportunity exists for clinicians to join more traditional policy players, such as lobbyists and think tanks. They can share patients’ powerful perspectives with policy makers to inform more equitable policies to improve family financial stability and maternal mental health.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, all participants spoke English and lived in one urban area in New England. Their experiences may not, therefore, reflect the experiences of other women with young children who experience financial strain but come from different linguistic and/or geographic backgrounds. Second, our observations are limited to interview discussions. Even though we interviewed participants until we reached thematic saturation, additional important themes may exist that our participants did not raise. Finally, financial strain is not limited to low-income women. Fifty-five percent of Americans report they experience financial strain (Pew Charitable Trusts, 2015). Although we intended to explore financial strain in settings of poverty and low income, the themes we identified, particularly those that relate to the interactions among financial strain, pregnancy, and mental health, may pertain to women in higher income brackets as well. Despite these limitations, our findings highlight important themes that may increase the effectiveness and relevance of interventions to alleviate financial strain and improve health for families.

Recommendations

Our findings illuminate the significant effect financial strain has on women with young children. Women’s health care providers may be particularly well positioned to provide additional supports to address financial strain and its mental health effects. Screening for both social needs and mental health conditions is becoming the standard of care in many medical homes. However, linking these screenings together has not been explored in practice or the literature to date. Researchers can add to the evidence base if they study whether addressing material needs could be an effective intervention for poor maternal mental health.

At the same time, the financial strain many of our participants experienced stemmed from structural problems that require social and political change. In the meantime, understanding that women experience self-blame, validating their feelings during clinical encounters, and acknowledging the systems-level obstacles they face to decrease financial strain may be a therapeutic starting point. Health care providers should simultaneously join the societal movement for stronger social policies such as an increased minimum wage, paid sick and parental leave, expansion of child care subsidies, and stronger food support programs. Their unique perspectives and patient stories could make an important difference in policy change. Hearing these stories could inspire other citizens to join the movement advocating for policy change. As Lathrop (2020) stated, “Social determinants of health stand in direct opposition to the achievement of health equity in the United States … [and] largely stem from structural racism and historical discrimination against marginalized populations” (p. 38). Future studies should evaluate the reproducibility of the explanatory model we developed and its applications to different populations.

Conclusion

Financial strain significantly affects women with young children. Women identify pregnancy as a particularly salient trigger of financial strain, struggle with tradeoffs because of insufficient resources, and modify their parenting as a result. They blame themselves for these problems and ensuing modifications, with resultant significant mental health problems. Women’s health providers should maximize supports for families and fight for stronger health and economic policies to address structural causes of poverty. Our theoretical model describes the effect of financial strain on parenting, including forced tradeoffs, compromised parenting practices, and maternal mental health, including self-blame, anxiety, and depression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Funded by the Claniel Foundation Emerging Leaders Fund and the Medical Staff Organization House Officer Development Award (Boston Children’s Hospital).

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest or relevant financial relationships.

Supplementary Material

Note: To access the supplementary material that accompanies this article, visit the online version of the Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing at http://jognn.org and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogn.2020.07.002

Contributor Information

Lucy E. Marcil, Department of Pediatrics, Boston University School of Medicine and Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA.

Jeffrey I. Campbell, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Pediatrics, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

Katie E. Silva, associate at ideas42, New York, NY

Diána Hughes, Fredrick S. Pardee School of Global Studies, Boston University, Boston, MA.

Saraf Salim, Department of Pediatrics, Boston University School of Medicine and Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA.

Hong-An T. Nguyen, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital at Montefiore and Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY.

Katherine Kissler, College of Nursing, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO.

Michael K. Hole, Department of Pediatrics, Dell Medical School, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX.

Catherine D. Michelson, Department of Pediatrics, Boston University School of Medicine and Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA.

Caroline J. Kistin, Department of Pediatrics, Boston University School of Medicine and Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA.

REFERENCES

- Albelda R, & Carr M (2017). Combining earnings with public supports: Cliff effects in Massachusetts. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/communities-and-banking/2017/winter/combining-earnings-with-public-supports-cliff-effects-in-massachusetts.aspx [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2016). Poverty and child health in the United States. Pediatrics, 137(4), e20160339. 10.1542/peds.2016-0339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Nurse Midwives. (2018). ACNM position statement: Social justice, http://www.midwife.org/acnm/files/ACNMLibraryData/UPLOADFILENAME/000000000317/PS-Social-Justice.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, & Bassett ΜT (2017). Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet, 389(10077), 1453–1463. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AR, Riley CL, Taylor SC, Brokamp C, & Kahn RS (2018). Pervasive income-based disparities in inpatient bed-day rates across conditions and subspecialties. Health Affairs, 37(4), 551–559. 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmans RS, Berger LM, Palta M, Robert SA, Ehrenthal DB, & Malecki K (2018). Participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and maternal depressive symptoms: Moderation by program perception. Social Science and Medicine, 197, 1–8. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beverly EA, Ritholz MD, Brooks KM, Hultgren BA, Lee Y, Abrahamson MJ, & Weinger K (2012). A qualitative study of perceived responsibility and self-blame in type 2 diabetes: Reflections of physicians and patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27(9), 1180–1187. 10.1007/s11606-012-2070-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birks M, & Mills J (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Blau FD, & Kahn LM (2013). Female labor supply: Why is the United States falling behind? American Economic Review, 103(3), 251–256. 10.1257/aer.103.3.251 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bourke-Taylor H, Howie L, & Law M (2011). Barriers to maternal workforce participation and relationship between paid work and health. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 55(5), 511–520. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01407.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, & Conger KJ (2002). Resilience in Midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective, longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(2), 361–373. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00361.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne IT (1997). Sampling in qualitative research. Purposeful and theoretical sampling; merging or clear boundaries? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26(3), 623–630. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997401-25-00999.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czapp P, & Kovach K (2015). Poverty and health—The family medicine perspective [Position Paper], American Academy of Family Physicians. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/policy-povertyhealth.html [Google Scholar]

- Damaske S, Bratter JL, & Freeh A (2017). Single mother families and employment, race, and poverty in changing economic times. Social Science Research, 62, 120–133. 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2016.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond M (2016). Evicted: Poverty and profit in the American city. Broadway Books. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra-Kersten SMA, Biesheuvel-Leliefeld KEM, van der Wouden JC, Penninx BWJH, & van Marwijk HWJ (2015). Associations of financial strain and income with depressive and anxiety disorders. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 69(1), 660–665. 10.1136/jech-2014-205088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank C, Davis CG, & Elgar FJ (2014). Financial strain, social capital, and perceived health during economic recession: A longitudinal survey in rural Canada. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 27(4), 422–438. 10.1080/10615806.2013.864389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, & Strauss A (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Transaction. [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heerink F, Krumeich A, Feron F, & Goga A (2019). ‘We are the advocates for the babies’—Understanding interactions between patients and health care providers during the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in South Africa: A qualitative study. Global Health Action, 12(1), Article 1630100. 10.1080/16549716.2019.1630100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell EA, Brown H, Brumley J, Bryant AS, Caughey AB, Cornell AM, … Grobman WA (2018). Reduction of peripartum racial and ethnic disparities: A conceptual framework and maternal safety consensus bundle. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 47(3), 275–289. 10.1016/j.jogn.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendig S, Keats JP, Hoffman MC, Kay LB, Miller ES, Simas TAM, … Lemieux LA (2017). Consensus bundle on maternal mental health: Perinatal depression and anxiety. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health, 62(2), 232–239. 10.1111/jmwh.12603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange BCL, Dáu ALBT, Goldblum J, Alfano J, & Smith MV (2017). A mixed methods investigation of the experience of poverty among a population of low-income parenting women. Community Mental Health Journal, 53(1), 832–841. 10.1007/s10597-017-0093-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lathrop B (2020). Moving toward health equity by addressing social determinants of health. Nursing for Women’s Health, 24(1), 36–44. 10.1016/j.nwh.2019.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luca DL, Garlow N, Staatz C, Margiotta C, & Zivin K (2019). Societal costs of untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. Mathematica. https://www.mathematica.org/our-publications-and-findings/publications/societal-costs-of-untreated-perinatal-mood-and-anxiety-disorders-in-the-united-states [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luca DL, Margiotta C, Staatz C, Garlow E, Christensen A, & Zivin K (2020). Financial toll of untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders among 2017 births in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 110(6), 888–896. https://doi-org.ezproxy.bu.edu/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons S, Arcara J, Deardorff J, & Gomez AM (2019). Financial strain and contraceptive use among women in the United States: Differential effects by age. Women’s Health Issues, 29(2), 153–160. 10.1016/j.whi.2018.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masarik AS, & Conger RD (2017). Stress and child development: A review of the Family Stress Model. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 85–90. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKernan SM, Ratcliffe C, Steuerle CE, & Zhang S (2013). Less than equal: Racial disparities in wealth accumulation. Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Murray TA (2018). Overview and summary: Addressing social determinants of health: Progress and opportunities. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 23(3). 10.3912/OJIN.Vol23No03ManOS [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. (2019). A roadmap to reducing child poverty. 10.17226/25246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick K (2017). National snapshot: Poverty among women & families, 2016. National Women’s Law Center, https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Poverty-Snapshot-Factsheet-2017.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Pew Charitable Trusts. (2015). Americans’ financial security: Perception and reality https://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2015/02/fsm-poll-results-issue-brief_artfinal_v3.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Roll S, & East J (2014). Financially vulnerable families and the child care cliff effect. Journal of Poverty, 18(2), 169–187. 10.1080/10875549.2014.896307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shippee TP, Wilkinson LR, & Ferraro KF (2012). Accumulated financial strain and women’s health over three decades. Journals of Gerontology—Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67(5), 585–594. 10.1093/geronb/gbs056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon D, Mclnerney M, & Goodell S (2018). The earned income tax credit, poverty, and health. Health Affairs. 10.1377/hpb20180817.769687 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, & Corbin J (1990). Basics of qualitative research. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Sufrin C, Davidson A, & Markenson G (2018). Importance of social determinants of health and cultural awareness in the delivery of reproductive health care. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 131(1), E43–E48. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A, Rangan GK, Ruospo M, Saglimbene V, Strippoli GFM, Palmer SC, … Craig JC (2015). A painful inheritance—Patient perspectives on living with polycystic kidney disease: Thematic synthesis of qualitative research. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, 30(5), 790–800. 10.1093/ndt/gfv010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy SJ (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851. 10.1177/1077800410383121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Labor. (2018). Mothers and families. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/wb/data/mothers-and-families [Google Scholar]

- Wahlbeck K, Cresswell-Smith J, Haaramo R, & Parkkonen J (2017). Interventions to mitigate the effects of poverty and inequality on mental health. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(5), 505–514. 10.1007/s00127-017-1370-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker KC, Arbour MW, & Wika JC (2019). Consolidation of guidelines of postpartum care recommendations to address maternal morbidity and mortality. Nursing for Women’s Health, 23(6), 508–517. 10.1016/j.nwh.2019.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham S, Whitehead M, Taylor-Robinson D, & Barr B (2017). The effect of a transition into poverty on child and maternal mental health: A longitudinal analysis of the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Lancet Public Health, 2(3), e141–e148. 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30011-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.