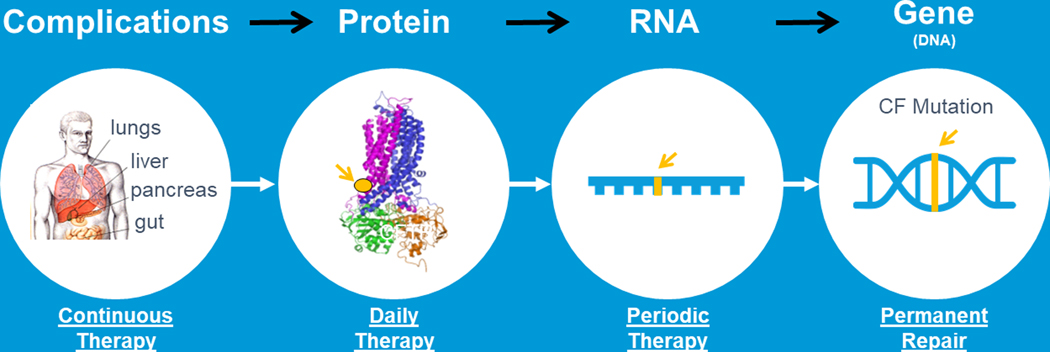

2019 will be remembered as a landmark year for the Cystic Fibrosis (CF) community because it marks the year when effective modulator therapy became available for most CF patients[1–3]. effective modulator therapy has the potential to change the trajectory of patients’ health and long-term outcomes. These therapies optimize the function of the patients’ endogenous mutant Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR), which results in return of CFTR channel function [1,2,4–6]. Although the combination of high throughput screening of small molecule libraries and medicinal chemistry have resulted in amazing new effective modulator therapies for many, it is unlikely that this approach will provide a game changing therapy for all. In part because the response to even the most promising modulator therapy is variable and an area of active investigation. Also, there are about 10% of patients with CF who don’t produce a mutant protein to modulate, potentiate or optimize and for these patients such therapies are unlikely to be of significant benefit. Efforts to develop small molecule therapy to promote protein production in patients with nonsense mutations such as PTC124 has proved to be far more challenging than predicted [7]. There is a need to develop new therapeutic approaches that can work for this patient population. These new therapies will be genetic-based therapies that include ribonucleic acid (RNA) therapies, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) therapies and gene editing technologies. Each approach will result in functional CFTR expression in CF affected cells. Ideally, these approaches would require less frequent dosing than effective modulators, which are given daily. For instance, RNA based treatments could be given periodically. Ultimately, treatment with certain gene-altering treatments could be given once in a lifetime and lead to a permanent cure (Figure 1). In this review which is based on Plenary 1 from the North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference in 2019 which is based on Plenary 1 from the North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference in 2019 we will examine the potential of RNA therapies, gene transfer therapies and gene editing therapies for the treatment of CF[8–13], as well as the challenges that will need to be faced as we harness the power of these emerging therapies towards a one-time cure.

FIGURE 1.

A lifelong Cure for all CF patients. For the complications of CF we have developed many CF therapies that are delivered multiple times a day; newly developed highly effective modulators provide once to twice daily therapies that improve CFTR function; emerging RNA therapies would be delivered periodically instead of daily; gene transfer and /or gene editing approaches would provide permanent repair if delivered to self‐renewing cells. (Adapted from Plenary 1 of NACFC 2019). CF, cystic fibrosis; CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

RNA

When considering RNA as a therapeutic agent we need to consider a variety of RNA molecules. RNA is a single stranded nucleic acid that is composed of nucleotide bases that are connected with a ribose phosphate backbone it is essential for many cell functions as including controlling gene expression, protein synthesis and the transfer of amino acids. There are many RNA types, however only some of these molecules are under investigation for their therapeutic potential in CF. They include messenger RNA (mRNA), transfer RNA (tRNA) and smaller RNA molecules called oligonucleotides. Certain RNA approaches are likely to benefit distinct subsets of CF patients. For instance, engineered transfer RNAs are likely to be beneficial to those patients with nonsense mutations. In contrast, mRNA therapy will likely benefit all patients with CF, so it is mutation agnostic. Antisense oligonucleotides have the potential to help those with a variety of mutations including splicing mutations.

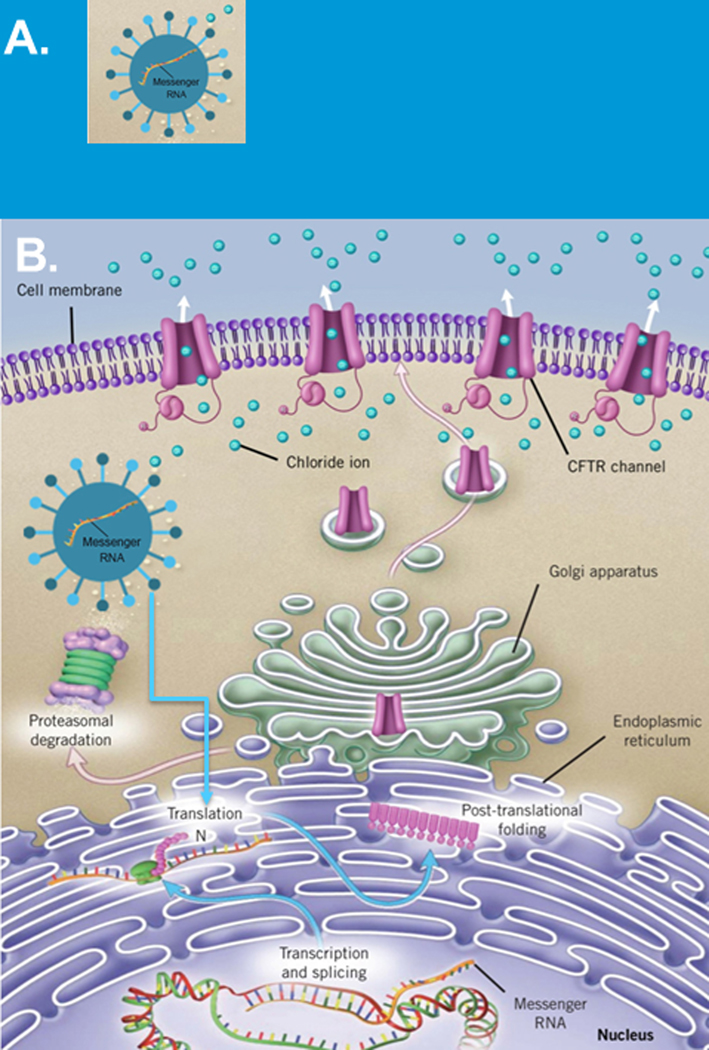

First, we will examine the potential of mRNA as a therapeutic (figure 2). mRNA is the blueprint for making proteins, like CFTR. Normally mRNA is transcribed from DNA in the nucleus before is leaves the nucleus traveling to the endoplasmic reticulum, the protein synthesizing machinery in the cell, where the ribosome will translate the mRNA into a protein. Subsequently, the protein moves through the Golgi apparatus where final protein modifications occur before the protein moves to its destination, which for CFTR is, the cell membrane.

FIGURE 2.

mRNA approaches for cystic fibrosis. A, mRNA encapsulated in a specialized delivery vehicle to protect it from degradation and facilitate delivery B, Schematic showing mRNA once delivered has a complex journey before CFTR protein is delivered to the cell surface (adapted from Plenary 1 of NACFC 2019). CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; mRNA, messenger RNA

To restore CFTR function by delivering mRNA, mRNA will need to be delivered to critical cell types. Delivery will be difficult for multiple reasons including the size of the molecule and therefore requires unique delivery systems that will be able to protect and facilitate its delivery (Figure 2A) [11,14]. Once mRNA is delivered, it will need to be able to be recognized by the protein assembly apparatus in the cell so that the blueprint, mRNA, will be properly deciphered resulting in full length CFTR proteins which traffic to the cell surface (Figure 2B). Clearly, this is a complex process with multiple check points and choke points that must be overcome.

Today there are clinical trials investigating the potential of mRNA in many diseases including CF. One such trial is the RESTORE-CF trial, (NCT03375047) which is examining a specialized nanoparticle carrier for mRNA, that is composed of lipids. The investigational drug, MRT5005, is aerosolized and inhaled into the lung. Changes in lung function, that is changes in FEV1 will be assessed as an outcome measure. The results from this study may provide proof of principle that mRNA may be a viable emerging therapy for CF.

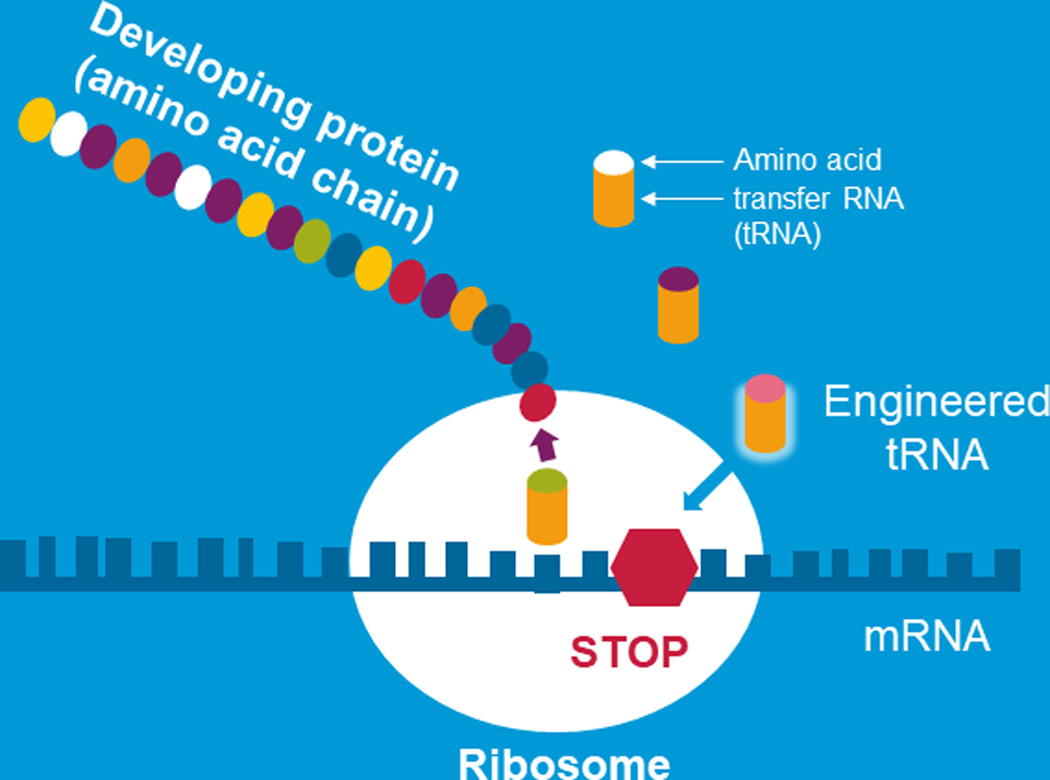

Another RNA approach that could be implemented to overcome nonsense mutations is engineered transfer RNAs. Engineered transfer RNAs are designed to introduce an amino acid to an elongating peptide in place of allowing a stop codon to lead to termination of protein production [15]. tRNAs are small RNA molecules that play a pivotal role in protein production. Figure 3 graphically shows mRNA as it is being decoded by the ribosome and the message is being translated into a developing protein. This happens with the help of tRNAs which are specialized RNAs that couple with the mRNA and ferry the amino acids the building blocks of proteins to the ribosome to allow for the elongation of the peptide. tRNAS bring the amino acids to the ribosome which builds the protein. When there is a nonsense mutation, a premature stop codon, in the mRNA there is no transfer RNA with an amino acid to add to the developing protein and protein production stops. However, engineered tRNAs recode the termination codon by adding an amino acid building block and the peptide continues to be made. In work from several investigators including the Lueck lab this approach has been successful at promoting read through stop codons in CF airway epithelial cells that were treated in culture leading to full length CFTR protein [15].

FIGURE 3.

Engineered transfer RNAs to overcome premature stop mutations. Schema models how engineered transfer RNAs (adapted from Plenary 1 of NACFC 2019)

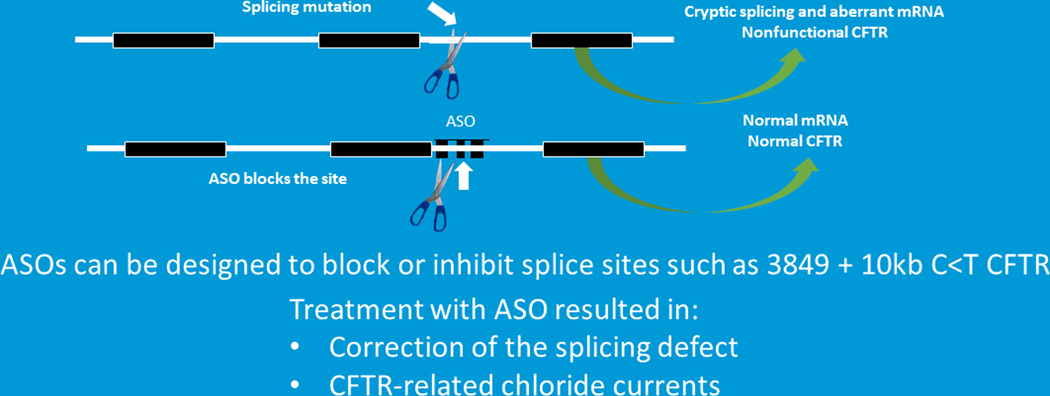

In addition to the above-mentioned RNA approaches there is also antisense RNA oligonucleotide therapy. Antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) are small pieces of single strand RNA that are designed to either block/interfere with mRNA production; or enable mRNA degradation or enhance mRNA production [12]. Although there have been over 40 clinical trials exploring the clinical potential of antisense oligonucleotides only 4 medications have received Federal Drug Administration (FDA) approval. None of the FDA approved drugs are for CF [8,12]. This serves a reminder of how difficult it is to move a promising agent across the therapeutic finish line. So how might ASOs be used in CF? There are several mutation classes that might benefit from ASOs including splice site mutations [8,16,17]. Splice site mutations, such as 3489C>G + 10KB, introduce a cryptic site that leads to splicing and an aberrant mRNA and nonfunctional protein (Figure 4). Investigational teams are developing ASOs to block the cryptic splice site so that normal mRNA is produced and full length CFTR protein is produced and functional. Dr Kerem and colleagues developed specialized ASOs for the 3849C>G +10KB mutation. When airway epithelial were treated with these ASOs CFTR is correctly spliced and normal protein is produced. In addition, CFTR function is restored to normal.

FIGURE 4.

RNA therapies. Antisense oligonucleotides can be used in a variety of mutations (Adapted from Plenary 1 of NACFC 2019). CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

So, to summarize there are a few RNA approaches that have potential as therapeutics in CF. Many of these RNA approaches are being developed into potential therapeutics for CF. However, there are challenges that will need to be overcome before these approaches will be viable treatments. The challenges include but are not limited to efficient delivery of the therapeutic agent to all critical tissues; ensuring there is RNA stability so that there is some longevity to the treatment; and understanding and limiting the potential for off target effects and toxicity of the reagents [12].

Gene therapy/ Gene editing

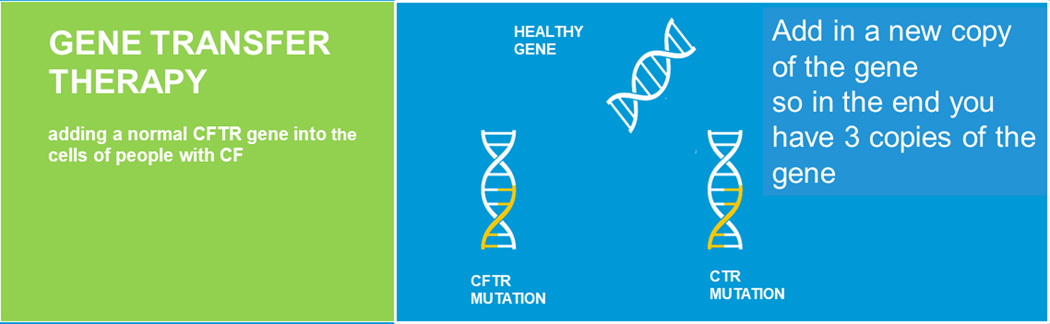

Additional nucleic acid approaches are gene transfer therapy, where a healthy copy of the gene is introduced into cells (Figure 5) and gene editing where instead of providing cells with an additional copy of the CFTR gene, the endogenous CFTR is repaired (Figure 6) [8,9]. For gene repair to happen the endogenous mutation needs to be corrected. There are a variety of gene editing tools that can be employed to accomplish this correction.

FIGURE 5.

Gene transfer therapy (adapted from Plenary 1 of NACFC 2019). CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

FIGURE 6.

Gene editing therapy (adapted from Plenary 1 of NACFC 2019). CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

Gene therapy is not a new idea for the CF community. The concept was introduced during a Plenary session at the 1989 North American Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Conference by James Wilson, MD PhD. who discussed the potential use of adenoviral vectors to deliver the newly identified CFTR gene to the airways of patients with CF. Subsequently, there were major research programs that developed potential gene therapy vectors and multiple clinical trials were undertaken to deliver CFTR to airway cells, but these attempts did not lead to significant consistent clinical efficacy, even though there may have been some level of correction [18–26]. However, these studies and the research efforts have taught us an enormous amount and has moved the field forward.

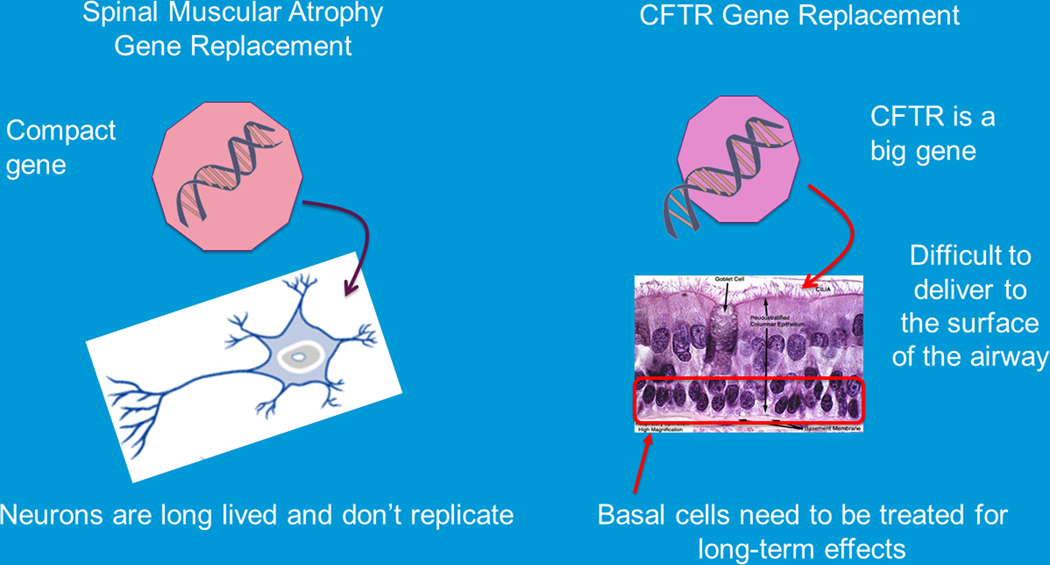

Today, gene therapy which fits into a larger regenerative medicine umbrella where there are over 1000 Phase1 studies and over 500 phase 2 studies and almost 100 phase 3 studies underway. The FDA has approved gene therapeutic agents for a number of diseases including certain cancers[27,28], thalassemia [29–31], inherited blindness[32,33], as well as spinal muscular atrophy type 1 (SMA)[34]. SMA is a devastating disease in which most children die from complications of their neurodegenerative disease by their second birthday, but now with effective gene therapy, patients are living ventilator-free for far longer than ever imagined [34–36]. In all these cases where gene therapy has moved to the therapeutic arena researchers have been able to optimize the delivery of the gene therapy vector. Of note in many of these successes the gene therapy vector only needed to be delivered to a single cell type or a limited body area which can be contrasted to the needs of a subject with CF (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

Challenges for gene transfer or gene editing in cystic fibrosis. Challenges include the size of the gene which impedes (adapt proper packaging into a delivery system; delivery to airway cells is difficult; delivery to progenitor/basal cells; multiple tissues that need to be targeted (adapted from Plenary 1 of NACFC 2019 and the CFF Community Research forum). CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

The last large gene therapy clinical trial for CF was conducted by the United Kingdom (UK) consortium and competed in 2014[13,37–39]. This study introduced a non-viral vector delivered to the airway repeatedly over a year’s time. The results showed that the therapy was very safe well tolerated but the efficacy was very modest which was likely related to inefficient delivery of the gene therapy particles to the needed cells. So, similar to RNA therapies for gene transfer therapies delivery is our biggest challenge and has been the major focus of research efforts. Developing high efficiency vectors that can improve deliver the CFTR gene to the necessary cells is of utmost importance. Vectors or delivery systems can be derived from viruses, such as adeno associated virus (AAV) or lentiviruses or they can be made from lipids and polymers. Regarding viral vectors investigators are not just relying on nature to develop a perfect virus instead they are working on designing the best virus capsid they can. Steines and colleagues at the University of Iowa have developed designer vectors that have much higher affinity for the airway cells that we need to correct in CF [40]. They developed a library of all the proteins in the viral capsid and by putting them together in multiple variations and then delivering them to a pig they were able identify the viral capsid that worked the best at delivering cargo to airway cells. The same approach can be used to identify the best delivery system to target any tissue. A similar strategy was developed with lipid and polymer-based vectors as reported by Dahlmans and colleagues [41,42]. They have developed an approach that is designed identifying the best particles for systemic delivery thus targeting all the tissues affected in CF. There are several major CF gene therapy programs that are using these, state of the art, approaches to identify and design optimal vectors for high efficiency delivery so that gene therapy can move forward for cystic fibrosis.

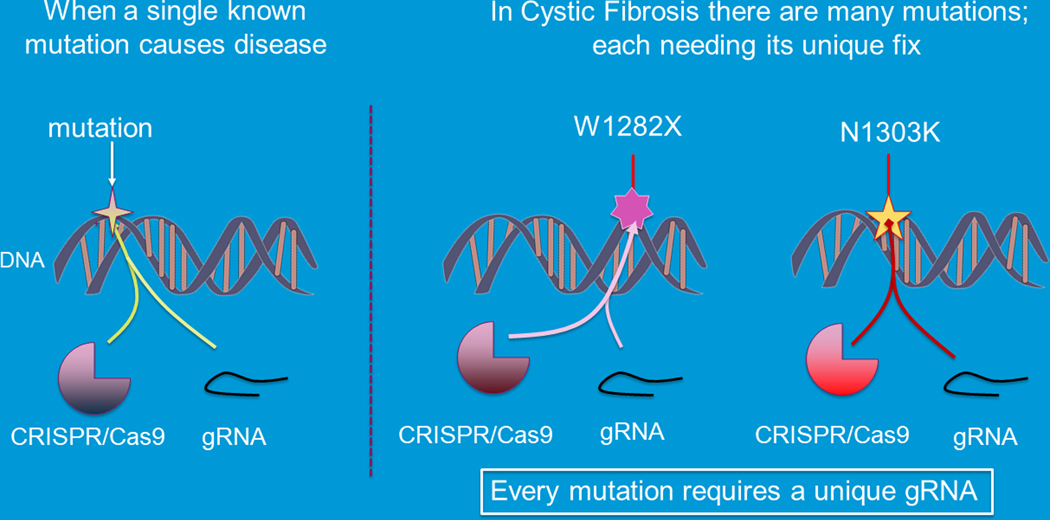

Next, we will review the many gene editing technologies available to edit or alter a patient’s gene to correct the sequence mutation. There are several -clinical trials exploring the potential of these therapies for treatment of a variety of human diseases including cancer, sickle cell disease and retinal diseases. Many gene editing approaches have been used to correct CFTR mutations including clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR/Cas)[43], zinc finger nucleases (ZFN) [44–48], transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENS)[49] and triplex forming peptide nucleic acid (PNA)/DNA [50,51]. All the gene editing work in CF is in the preclinical realm [52]. CF will have unique challenges with CFTR gene that lead to disease. Each mutation will need its unique editing tools to repair the error in the gene (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8.

Challenges for gene editing in CF. Multiple mutations (Adapted from Plenary 1 of NACFC 2019 and the CFF Community Research forum). CF, cystic fibrosis; gRNA, genomic RNA

Zinc finger nucleases have been used to correct airway epithelial cells. Crane and colleagues showed ZFN could correct CFTR and restore CFTR function in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)[48]. CRISPR/Cas9 has been used to correct CFTR and restore function in intestinal organoids from CF patients [43]. In these experiments, cells were obtained from patients via rectal biopsy and then the cells grown and expanded in culture where they formed small replica of the intestine called organoids. Investigators introduced CRISPR/Cas9 editing tools to the organoids to correct the CFTR mutation and then compared CFTR activity in the treated organoids compared to the untreated organoids using a swelling assay. They were able to observe significant CFTR function in the treated organoids demonstrating they could correct CFTR.

Lastly, the triplex forming PNA/DNA approach relies on designing small peptide nucleic acids which are nucleic acids that are like DNA but have a peptide backbone instead of a sugar backbone [51,53,54]. PNAs can be designed so that will bind to DNA near a mutation that you want to correct. When this PNA is delivered to a cell with a donor DNA, the cell’s endogenous repair systems get alerted that the PNA has bound to the DNA and distorts the DNA helix, which triggers endogenous repair systems to be activated thus allowing for recombination and correction of the mutation. PNA/DNA delivered to cells via nanoparticles to CF airway epithelial cells can restore CFTR function in CF cells with the W1282X mutation, the G542X mutation, as well as the F508del mutation [51,53,54]. PNA/DNA nanoparticles can be delivered in vivo by inhalation or systemically in mouse models of CF [53]. When the particles are delivered topically we can see changes in respiratory tract. When they are delivered systemically we can see changes in both the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts.

Cell Based Therapies

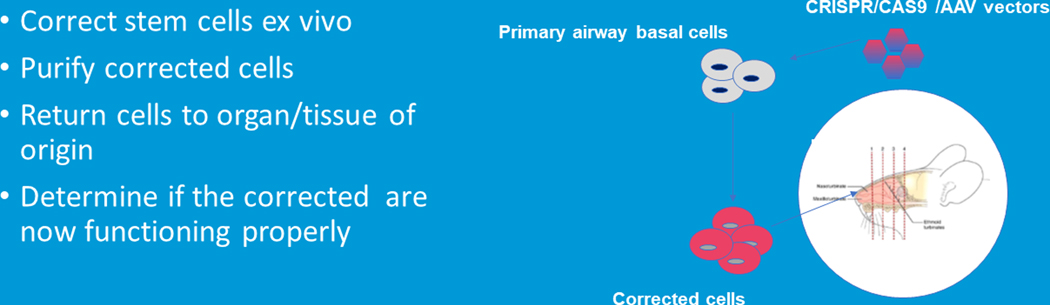

Cell based therapies correct a gene defect ex-vivo and then corrected cells are returned to the patient. This approach has been a very effective cancer therapy such as CAR T therapy [27,28], and for epidermolysis bullosa, a rare skin disease[55–57]. But will this work in CF? To be a viable option for the CF community, CF affected cells would need to be corrected using one of the new gene editing or gene transfer technologies in the laboratory. Subsequently, the corrected cells would be delivered to the appropriate organ of interest where they would need to function properly [58–60]. We do have an example that this is possible. The proof of principal comes from investigators at Stanford University who have taken primary CF airway basal cells and treated them with Cas9 delivered by AAV vectors to correct the gene defect (Figure 9). Then, purified corrected basal cells were put into the sinus cavity of a rat to see if they could grow into proper sinus cells, which they did. Although these are preliminary data they are encouraging and demonstrate the promise and potential of cell-based therapy[61].

FIGURE 9.

Cell based therapies: proof of principle (Adapted from Plenary 1 of NACFC 2019)

Summary and challenges:

There are many novel genetic approaches that get to the heart of the CF problem, overcoming a defective gene and there have been many advances in the nucleic acid therapeutic field that make these approaches much more feasible as potential treatments. But, there are many challenges that we will need to overcome before any of these approaches will become available in the clinical realm including but not limited to identifying which organs need to be targeted to yield the most robust effect with the least amount of potential harm; identifying which cells will need to be targeted in each organ; we will need to understand what a success treatment looks like, what are the most reliable biomarkers to track, and what are the safety signals we need to follow to ensure we do not cause harm and how do we design clinical trials given the small number of subjects that may be available for these ground breaking studies. Another challenge to consider is that unlike the clinical development of many other therapeutics gene therapy and gene editing will require that we move clinical trials ahead without data on healthy adult control cohorts, instead phase 1 studies will require CF subjects. In addition, for the approaches that are mutation agonist we will need to consider which patients should be included in the initial studies; should we include all patients even if there is effective modulator therapy for subjects or do we include only those with no current therapeutic options. Clearly, if we’re going to be successful, we have some significant challenges to tackle and we will need to do this as the collaborative community we have always been.

References

- 1.Middleton PG, Mall MA, Drevinek P, Lands LC, McKone EF, Polineni D, Ramsey BW, Taylor-Cousar JL, Tullis E, Vermeulen F, et al. : Elexacaftor-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor for Cystic Fibrosis with a Single Phe508del Allele. N Engl J Med 2019, 381:1809–1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keating D, Marigowda G, Burr L, Daines C, Mall MA, McKone EF, Ramsey BW, Rowe SM, Sass LA, Tullis E, et al. : VX-445-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis and One or Two Phe508del Alleles. N Engl J Med 2018, 379:1612–1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heijerman HGM, McKone EF, Downey DG, Van Braeckel E, Rowe SM, Tullis E, Mall MA, Welter JJ, Ramsey BW, McKee CM, et al. : Efficacy and safety of the elexacaftor plus tezacaftor plus ivacaftor combination regimen in people with cystic fibrosis homozygous for the F508del mutation: a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019, 394:1940–1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison MJ, Murphy DM, Plant BJ: Ivacaftor in a G551D homozygote with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2013, 369:1280–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies JC, Moskowitz SM, Brown C, Horsley A, Mall MA, McKone EF, Plant BJ, Prais D, Ramsey BW, Taylor-Cousar JL, et al. : VX-659-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis and One or Two Phe508del Alleles. N Engl J Med 2018, 379:1599–1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowe SM, Daines C, Ringshausen FC, Kerem E, Wilson J, Tullis E, Nair N, Simard C, Han L, Ingenito EP, et al. : Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor in Residual-Function Heterozygotes with Cystic Fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2017, 377:2024–2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerem E, Konstan MW, De Boeck K, Accurso FJ, Sermet-Gaudelus I, Wilschanski M, Elborn JS, Melotti P, Bronsveld I, Fajac I, et al. : Ataluren for the treatment of nonsense-mutation cystic fibrosis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med 2014, 2:539–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christopher Boyd A, Guo S, Huang L, Kerem B, Oren YS, Walker AJ, Hart SL: New approaches to genetic therapies for cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2020, 19 Suppl 1:S54–S59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hodges CA, Conlon RA: Delivering on the promise of gene editing for cystic fibrosis. Genes Dis 2019, 6:97–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mention K, Santos L, Harrison PT: Gene and Base Editing as a Therapeutic Option for Cystic Fibrosis-Learning from Other Diseases. Genes (Basel) 2019, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pranke I, Golec A, Hinzpeter A, Edelman A, Sermet-Gaudelus I: Emerging Therapeutic Approaches for Cystic Fibrosis. From Gene Editing to Personalized Medicine. Front Pharmacol 2019, 10:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sasaki S, Guo S: Nucleic Acid Therapies for Cystic Fibrosis. Nucleic Acid Ther 2018, 28:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griesenbach U, Davies JC, Alton E: Cystic fibrosis gene therapy: a mutation-independent treatment. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2016, 22:602–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson E, MacDonald KD, Slaughter K, McKinney M, Patel S, Sun C, Sahay G: Lipid Nanoparticle-Delivered Chemically Modified mRNA Restores Chloride Secretion in Cystic Fibrosis. Mol Ther 2018, 26:2034–2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lueck JD, Yoon JS, Perales-Puchalt A, Mackey AL, Infield DT, Behlke MA, Pope MR, Weiner DB, Skach WR, McCray PB Jr., et al. : Engineered transfer RNAs for suppression of premature termination codons. Nat Commun 2019, 10:822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oren YS, Pranke IM, Kerem B, Sermet-Gaudelus I: The suppression of premature termination codons and the repair of splicing mutations in CFTR. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2017, 34:125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiba-Falek O, Kerem E, Shoshani T, Aviram M, Augarten A, Bentur L, Tal A, Tullis E, Rahat A, Kerem B: The molecular basis of disease variability among cystic fibrosis patients carrying the 3849+10 kb C-->T mutation. Genomics 1998, 53:276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moss RB, Milla C, Colombo J, Accurso F, Zeitlin PL, Clancy JP, Spencer LT, Pilewski J, Waltz DA, Dorkin HL, et al. : Repeated aerosolized AAV-CFTR for treatment of cystic fibrosis: a randomized placebo-controlled phase 2B trial. Hum Gene Ther 2007, 18:726–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grubb BR, Pickles RJ, Ye H, Yankaskas JR, Vick RN, Engelhardt JF, Wilson JM, Johnson LG, Boucher RC: Inefficient gene transfer by adenovirus vector to cystic fibrosis airway epithelia of mice and humans. Nature 1994, 371:802–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boucher RC, Knowles MR, Johnson LG, Olsen JC, Pickles R, Wilson JM, Engelhardt J, Yang Y, Grossman M: Gene therapy for cystic fibrosis using E1-deleted adenovirus: a phase I trial in the nasal cavity. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Hum Gene Ther 1994, 5:615–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher KJ, Choi H, Burda J, Chen SJ, Wilson JM: Recombinant adenovirus deleted of all viral genes for gene therapy of cystic fibrosis. Virology 1996, 217:11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engelhardt JF, Simon RH, Yang Y, Zepeda M, Weber-Pendleton S, Doranz B, Grossman M, Wilson JM: Adenovirus-mediated transfer of the CFTR gene to lung of nonhuman primates: biological efficacy study. Hum Gene Ther 1993, 4:759–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zabner J, Couture LA, Gregory RJ, Graham SM, Smith AE, Welsh MJ: Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer transiently corrects the chloride transport defect in nasal epithelia of patients with cystic fibrosis. Cell 1993, 75:207–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welsh MJ, Smith AE, Zabner J, Rich DP, Graham SM, Gregory RJ, Pratt BM, Moscicki RA: Cystic fibrosis gene therapy using an adenovirus vector: in vivo safety and efficacy in nasal epithelium. Hum Gene Ther 1994, 5:209–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagner JA, Nepomuceno IB, Messner AH, Moran ML, Batson EP, Dimiceli S, Brown BW, Desch JK, Norbash AM, Conrad CK, et al. : A phase II, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of tgAAVCF using maxillary sinus delivery in patients with cystic fibrosis with antrostomies. Hum Gene Ther 2002, 13:1349–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagner JA, Moran ML, Messner AH, Daifuku R, Conrad CK, Reynolds T, Guggino WB, Moss RB, Carter BJ, Wine JJ, et al. : A phase I/II study of tgAAV-CF for the treatment of chronic sinusitis in patients with cystic fibrosis. Hum Gene Ther 1998, 9:889–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang X, Wang GX, Zhou JF: CAR T Cell Therapy for Hematological Malignancies. Curr Med Sci 2019, 39:874–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gourd E: CAR T-cell cocktail therapy for B-cell malignancies. Lancet Oncol 2019, 20:e669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karponi G, Zogas N: Gene Therapy For Beta-Thalassemia: Updated Perspectives. Appl Clin Genet 2019, 12:167–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrison C: First gene therapy for beta-thalassemia approved. Nat Biotechnol 2019, 37:1102–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stower H: Gene therapy for beta thalassemia. Nat Med 2018, 24:1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bennett J: Gene therapy for color blindness. N Engl J Med 2009, 361:2483–2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bennett J, Wellman J, Marshall KA, McCague S, Ashtari M, DiStefano-Pappas J, Elci OU, Chung DC, Sun J, Wright JF, et al. : Safety and durability of effect of contralateral-eye administration of AAV2 gene therapy in patients with childhood-onset blindness caused by RPE65 mutations: a follow-on phase 1 trial. Lancet 2016, 388:661–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mendell JR, Al-Zaidy S, Shell R, Arnold WD, Rodino-Klapac LR, Prior TW, Lowes L, Alfano L, Berry K, Church K, et al. : Single-Dose Gene-Replacement Therapy for Spinal Muscular Atrophy. N Engl J Med 2017, 377:1713–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheridan C: Gene therapy rescues newborns with spinal muscular atrophy. Nat Biotechnol 2018, 36:669–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nizzardo M, Simone C, Rizzo F, Salani S, Dametti S, Rinchetti P, Del Bo R, Foust K, Kaspar BK, Bresolin N, et al. : Gene therapy rescues disease phenotype in a spinal muscular atrophy with respiratory distress type 1 (SMARD1) mouse model. Sci Adv 2015, 1:e1500078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alton EW, Boyd AC, Cheng SH, Cunningham S, Davies JC, Gill DR, Griesenbach U, Higgins T, Hyde SC, Innes JA, et al. : A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase IIB clinical trial of repeated application of gene therapy in patients with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2013, 68:1075–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alton E, Armstrong DK, Ashby D, Bayfield KJ, Bilton D, Bloomfield EV, Boyd AC, Brand J, Buchan R, Calcedo R, et al. : Repeated nebulisation of non-viral CFTR gene therapy in patients with cystic fibrosis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b trial. Lancet Respir Med 2015, 3:684–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alton EW, Boyd AC, Porteous DJ, Davies G, Davies JC, Griesenbach U, Higgins TE, Gill DR, Hyde SC, Innes JA, et al. : A Phase I/IIa Safety and Efficacy Study of Nebulized Liposome-mediated Gene Therapy for Cystic Fibrosis Supports a Multidose Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015, 192:1389–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steines B, Dickey DD, Bergen J, Excoffon KJ, Weinstein JR, Li X, Yan Z, Abou Alaiwa MH, Shah VS, Bouzek DC, et al. : CFTR gene transfer with AAV improves early cystic fibrosis pig phenotypes. JCI Insight 2016, 1:e88728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lokugamage MP, Sago CD, Dahlman JE: Testing thousands of nanoparticles in vivo using DNA barcodes. Curr Opin Biomed Eng 2018, 7:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lokugamage MP, Sago CD, Gan Z, Krupczak BR, Dahlman JE: Constrained Nanoparticles Deliver siRNA and sgRNA to T Cells In Vivo without Targeting Ligands. Adv Mater 2019, 31:e1902251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwank G, Koo BK, Sasselli V, Dekkers JF, Heo I, Demircan T, Sasaki N, Boymans S, Cuppen E, van der Ent CK, et al. : Functional repair of CFTR by CRISPR/Cas9 in intestinal stem cell organoids of cystic fibrosis patients. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 13:653–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bednarski C, Tomczak K, Vom Hovel B, Weber WM, Cathomen T: Targeted Integration of a Super-Exon into the CFTR Locus Leads to Functional Correction of a Cystic Fibrosis Cell Line Model. PLoS One 2016, 11:e0161072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee CM, Flynn R, Hollywood JA, Scallan MF, Harrison PT: Correction of the DeltaF508 Mutation in the Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator Gene by Zinc-Finger Nuclease Homology-Directed Repair. Biores Open Access 2012, 1:99–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suzuki S, Crane AM, Anirudhan V, Barilla C, Matthias N, Randell SH, Rab A, Sorscher EJ, Kerschner JL, Yin S, et al. : Highly Efficient Gene Editing of Cystic Fibrosis Patient-Derived Airway Basal Cells Results in Functional CFTR Correction. Mol Ther 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramalingam S, London V, Kandavelou K, Cebotaru L, Guggino W, Civin C, Chandrasegaran S: Generation and genetic engineering of human induced pluripotent stem cells using designed zinc finger nucleases. Stem Cells Dev 2013, 22:595–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crane AM, Kramer P, Bui JH, Chung WJ, Li XS, Gonzalez-Garay ML, Hawkins F, Liao W, Mora D, Choi S, et al. : Targeted correction and restored function of the CFTR gene in cystic fibrosis induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Reports 2015, 4:569–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xia E, Zhang Y, Cao H, Li J, Duan R, Hu J: TALEN-Mediated Gene Targeting for Cystic Fibrosis-Gene Therapy. Genes (Basel) 2019, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Economos NG, Oyaghire S, Quijano E, Ricciardi AS, Saltzman WM, Glazer PM: Peptide Nucleic Acids and Gene Editing: Perspectives on Structure and Repair. Molecules 2020, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McNeer NA, Anandalingam K, Fields RJ, Caputo C, Kopic S, Gupta A, Quijano E, Polikoff L, Kong Y, Bahal R, et al. : Nanoparticles that deliver triplex-forming peptide nucleic acid molecules correct F508del CFTR in airway epithelium. Nat Commun 2015, 6:6952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marson FAL, Bertuzzo CS, Ribeiro JD: Personalized or Precision Medicine? The Example of Cystic Fibrosis. Front Pharmacol 2017, 8:390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oyaghire SN, Quijano E, Piotrowski-Daspit AS, Saltzman WM, Glazer PM: Poly(Lactic-co-Glycolic Acid) Nanoparticle Delivery of Peptide Nucleic Acids In Vivo. Methods Mol Biol 2020, 2105:261–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ricciardi AS, Quijano E, Putman R, Saltzman WM, Glazer PM: Peptide Nucleic Acids as a Tool for Site-Specific Gene Editing. Molecules 2018, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eichstadt S, Barriga M, Ponakala A, Teng C, Nguyen NT, Siprashvili Z, Nazaroff J, Gorell ES, Chiou AS, Taylor L, et al. : Phase 1/2a clinical trial of gene-corrected autologous cell therapy for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. JCI Insight 2019, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lwin SM, Syed F, Di WL, Kadiyirire T, Liu L, Guy A, Petrova A, Abdul-Wahab A, Reid F, Phillips R, et al. : Safety and early efficacy outcomes for lentiviral fibroblast gene therapy in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. JCI Insight 2019, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marinkovich MP, Tang JY: Gene Therapy for Epidermolysis Bullosa. J Invest Dermatol 2019, 139:1221–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee RE, Miller SM, Mascenik TM, Lewis CA, Dang H, Boggs ZH, Tarran R, Randell SH: Assessing Human Airway Epithelial Progenitor Cells for Cystic Fibrosis Cell Therapy. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berical A, Lee RE, Randell SH, Hawkins F: Challenges Facing Airway Epithelial Cell-Based Therapy for Cystic Fibrosis. Front Pharmacol 2019, 10:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang SX, Green MD, de Carvalho AT, Mumau M, Chen YW, D’Souza SL, Snoeck HW: The in vitro generation of lung and airway progenitor cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Protoc 2015, 10:413–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vaidyanathan S, Salahudeen AA, Sellers ZM, Bravo DT, Choi SS, Batish A, Le W, Baik R, de la OS, Kaushik MP, et al. : High-Efficiency, Selection-free Gene Repair in Airway Stem Cells from Cystic Fibrosis Patients Rescues CFTR Function in Differentiated Epithelia . Cell Stem Cell 2020, 26:161–171 e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]