ABSTRACT

Emergency evacuation during a disaster may have serious health implications in vulnerable populations. After the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant (FDNPP) in March 2011, the Japanese central government immediately issued an evacuation order for residents living near the plant. There is limited information on the process of evacuation from medical institutions within the evacuation zone and the challenges faced. This study collected and analyzed publicly available resources related to the Futaba Kosei Hospital, located 3.9 km northwest of the FDNPP, and reviewed the hospital’s evacuation procedures. On the day of the accident at the FDNPP, 136 patients were admitted in the aforementioned hospital. The hospital’s director received information about the situation at the FDNPP from the local disaster task force and requested the immediate evacuation of all patients. Consequently, four patients, including those with an end-stage condition, died during the evacuation. Early intervention by external organizations, such as the Japan Self-Defense Forces, helped the hospital to complete the evacuation without facing major issues. However, despite such an efficient evacuation, the death of four patients suggests that a significant burden is placed on vulnerable people during emergency hospital evacuations. Those with compromised health experience a heavy burden during a nuclear disaster. It is necessary for hospitals located close to a nuclear power plant to develop a more detailed evacuation plan by determining the methods of communication with external organizations that could provide support during evacuation to minimize the burden on vulnerable patients.

Keywords: nuclear power plants, Japan, Fukushima nuclear accident, disasters, emergency services hospitals

INTRODUCTION

It is of the utmost importance for healthcare providers to protect the health of vulnerable patients. People with compromised health include older adults, those living with disabilities, and inpatients [1, 2]. Such people are considered vulnerable because they lack the ability to protect themselves and to independently maintain access to healthcare during emergency situations, including natural disasters [1, 3, 4]. Given such a background and considering the fact that vulnerable populations are likely to lose access to healthcare during emergency situations, it is essential for hospitals to set up necessary evacuation and care plans for such individuals in normal times.

Vulnerable populations are more likely to experience health problems during an emergency evacuation, which is required in the case of a natural disaster and other similar situations [5–7]. A recent study found that the mortality rate increased in residents evacuated from an aged care facility in a hurricane-prone area compared with that in those who were not evacuated [8–10]. When an extraordinary event or circumstance such as a natural disaster or a man-made incident occurs, all people, including vulnerable people, may need to evacuate. Since the number of natural disasters has been increasing worldwide, it is important to examine the impact of forced evacuation on the health of vulnerable populations. Understanding the impact of forced evacuation may help minimize the harm caused to vulnerable populations.

On 11 March 2011, the Great East Japan Earthquake (GEJE) and subsequent tsunami caused an accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant (FDNPP). An evacuation order was issued on the same day for residents living within a 3-km radius of the FDNPP. In the following days, the scope of the order was extended to those living within a 20-km radius of the plant. Members of communities around the plant were forced to evacuate the area [11]. Some vulnerable people, such as older individuals in nursing homes, those with disabilities and hospitalized patients within the evacuation zones, were among the residents who were forced to evacuate [12]. The Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) provided secondary emergency assistance for hospitals outside the evacuation zone (within 20–30 km of the FDNPP) in transporting patients, and no deaths were reported during transportation; however, there were shortages of human and material resources both inside and outside the hospitals [13, 14]. Records suggest an increase in the mortality rate in aged care facilities located within a 20–30 km zone of the FDNPP, which was attributable to the unexpected and sudden evacuation due to the accident at the FDNPP [15–18]. Compared with the evacuation procedures used in medical institutions outside the 20-km zone, more urgent and stringent evacuation procedures were implemented in those within the zone [19, 20]. However, to date, limited academic reports are available on how inpatients were evacuated from medical institutions in areas that were in the scope of the emergency evacuation order, as well as the difficulties faced during such an evacuation.

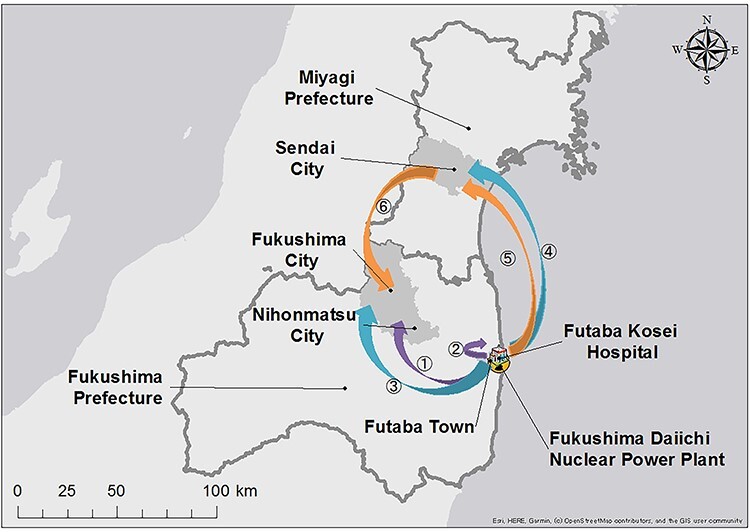

This study aimed to evaluate the process of emergency evacuation at Futaba Kosei Hospital, located within 5 km of the FDNPP (Fig. 1), with the aim of proposing measures to minimize potential risks in future cases of forced evacuation.

Fig. 1.

Location of municipalities during the evacuation process from Futaba Kosei Hospital. The geographical relationships between the FDNPP and Sendai, Nihonmatsu, Fukushima cities and Futaba Town are depicted. The arrows with numbers show the transportation methods, evacuation routes and evacuation destination. Purple arrows indicate transportation by land on 12 March 2011. Blue arrows indicate transportation by helicopter provided by the JSDF on 12 March 2011. Orange arrows indicate transportation by helicopter provided by the JSDF on 13 March 2011. The details of each arrow are as follows: arrow 1, 53 ambulatory patients and 90 employees evacuated to Nihonmatsu City via Kawamata Village; arrow 2, 35 patients (not accompanied by staff) evacuated using a truck provided by the JSDF to an unknown destination (possibly an aged care facility in Namie Town?); arrow 3, 21 patients and 21 hospital employees evacuated to Nihonmatsu City by the JSDF helicopter; arrow 4, 12 patients and 25 hospital employees evacuated to Sendai City by the JSDF helicopter on 12 March; arrow 5, 7 patients and 9 hospital employees evacuated to Sendai City by the JSDF helicopter on 13 March; arrow 6, a combination of patients and employees evacuated in arrows 4 and 5 headed from Sendai City to Nihonmatsu City by the JSDF helicopter on 13 March.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

STUDY SETTING AND PATIENTS

In Japan, before the FDNPP accident, the area within a 10-km radius of a nuclear power plant was designated as an emergency planning zone wherein disaster prevention measures were to be focused in the event of a nuclear power plant accident [21]. However, after the FDNPP accident, evacuation orders were issued regardless of this administrative zoning setup. Following the FDNPP accident, the Nuclear Regulation Authority of Japan designated the area within 5 km of a plant as a precautionary action zone and the area within 5–30 km of a plant as an urgent protective action planning zone.

In response to the FDNPP accident, the Japanese government revisited the nuclear disaster medical system and greatly revised the Nuclear Emergency Response Guideline since 2015 [22]. After the revision of this guideline, Nuclear Emergency Core Hospitals are hospitals located mainly in prefectures with nuclear facilities and provide treatment to individuals who are exposed to radiation, while Advanced Radiation Emergency Medical Support Centers are designated to support dose assessment and medical treatment for patients with serious radiation exposure. Additionally, Nuclear Emergency Medical Support Centers and Nuclear Emergency Medical Assistance Teams are designated to provide information/medical care during a nuclear disaster nationwide. These support centers also provide basic training services on nuclear disasters in other medical institutions.

There were seven hospitals in the area within a 20-km radius of the FDNPP, for which evacuation orders were issued immediately after the FDNPP accident, and the patients in all seven hospitals were forced to evacuate.

Futaba Kosei Hospital in Futaba Town, Futaba District, Fukushima Prefecture, Japan, is located 3.9 km northwest of the FDNPP. On 11 March 2011, when the GEJE occurred [23], the hospital had 260 beds and 225 employees (Fig. 1), including 10 full-time physicians. A total of 136 psychiatric and internal medicine patients were admitted in the hospital when the FDNPP accident occurred [23]. Since Futaba Kosei Hospital planned to merge its function with Fukushima Prefectural Ono Hospital, which was also located within a 5-km radius of the FDNPP in late March 2011, these two hospitals had reduced inpatient census at the time of the accident.

The FDNPP was extremely damaged from the tsunami, which occurred following the earthquake. On 11 March 2011, at 9:23 p.m., the Japanese central government issued an evacuation order for areas within a 3-km radius of the FDNPP. Thereafter, the area within a 10-km radius of the FDNPP was designated as an evacuation zone by government orders at 5:44 a.m. on 12 March 2011. Emergency hospital evacuation in Futaba Kosei Hospital commenced under the supervision of the hospital’s director following this order. On 12 March 2011, at 6:25 p.m., the evacuation order was extended to areas within a 20-km radius of the FDNPP.

STUDY DESIGN AND DATA COLLECTION

This study involved a retrospective review of the hospital’s evacuation process. This was performed using a house magazine published by the organization governing Futaba Kosei Hospital, which contained testimonies from hospital officials and other details of the evacuation process. This house magazine, consisting of two parts (total: 187 pages), provided detailed information regarding initial turmoil and confusion, the evacuation process and results.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Minamisoma Municipal General Hospital (approval number: 2–07) and Fukushima Medical University (approval number: 2019–269). The approval authority waived the requirement for obtaining written informed consent from study participants because the data that were analyzed were publicly available. Additionally, officials from Futaba Kosei Hospital approved the publication of this study.

RESULTS

PROCESS OF DECISION-MAKING FOR EVACUATION AND INITIAL EVACUATION

On 11 March 2011, at 2:46 p.m., an earthquake with a magnitude of 9.0 struck Japan. An intensity of upper 6 on the Japanese scale of 7 was recorded in Futaba Town, where the Futaba Kosei Hospital was located. Subsequently, a tsunami affected a region ~700 m from the hospital, leaving the hospital unharmed. Although many structures collapsed due to the earthquake, the hospital building was not damaged. The hospital’s power supply was undisrupted, and gas and water supply were recovered after implementing emergency measures. Oxygen and suction devices were still functioning. On the day of the earthquake, the hospital accepted 56 emergency patients who had sustained injuries related to the earthquake and tsunami. The hospital continued to provide healthcare.

On 12 March 2011, at ~6:40 a.m., two police officers in personal protective equipment accompanied by members of the JSDF visited the hospital. The officers requested the director of the hospital to initiate evacuation of the building, including the evacuation of patients. No clear reasons for evacuation were provided at that time. However, subsequent media coverage revealed that residents living within 10 km of the FDNPP had been ordered to evacuate. Taking these facts into account, the director decided to initiate the evacuation of a number of the hospitalized patients to reduce the patient census. At that time, the hospital accommodated 136 inpatients and 150 employees.

At ~8:30 a.m. on 12 March 2011, the evacuation of patients who could move independently was initiated. Six patients were discharged upon voluntary request. A total of 53 patients who could walk independently and 90 employees were evacuated using buses, and another 35 patients (not accompanied by staff) were evacuated using a truck provided by the JSDF. A woman who gave birth by cesarean section directly after the earthquake was transported via ambulance to Fukushima Medical University Hospital in Fukushima City with her newborn baby (Fig. 1). Since no updates were available on the situation at the FDNPP during the initial evacuation, the hospital’s director had difficulty in deciding whether patients with a severe condition should be evacuated or not. However, at ~2:00 p.m. on 12 March 2011, the director received a phone call from an old friend who was part of the Fukushima Disaster Task Force and was informed that the situation at the FDNPP was extremely serious. Therefore, the director decided to evacuate the remaining patients and staff members in the hospital building.

EVACUATING PATIENTS WITH A SERIOUS CONDITION

A total of 40 patients with a serious condition and 56 hospital employees remained in the hospital building after the initial evacuation. In the afternoon of 12 March 2011, after the director decided to conduct another evacuation procedure, the evacuation of all the remaining people was started. No patient evacuation plans were developed for a nuclear accident; however, the hospital staff exerted great efforts and worked together hand-in-hand to safely evacuate the remaining patients. Helicopters from the JSDF were used to transport the remaining people from the hospital to the Fukushima Gender Equality Centre in Nihonmatsu City (Fig. 1). A helipad was set up in the town. The hospital staff helped each other in transporting patients, using a truck provided by the JSDF, to the school grounds of Futaba High School, which was located 2 km away from the hospital. At 3:36 p.m., while patient transport was ongoing, a hydrogen explosion occurred at the FDNPP. At that time, 1 patient and 2 hospital employees were evacuated by police officers in a police car.

The JSDF helicopters (two large and five medium) arrived after 6:00 p.m. The people in the hospital were transported in groups (patients, physicians, other medical staff members and administration staff members), and each group boarded the helicopter one at a time. The decision for a grouped evacuation was made by the hospital staff on the spot. Twenty-one patients and 21 hospital employees boarded the first helicopter and headed to Nihonmatsu City. Several community members and residents of aged care facilities noticed the helicopters and requested to be evacuated as well; hence, they also boarded the helicopter and were evacuated. A total of 12 patients and 25 hospital employees boarded the second helicopter. The helicopter was redirected to the Kasuminome Air Field in Sendai City, Miyagi Prefecture, due to insufficient fuel and poor night-time visibility (Fig. 1). The deployed rescue helicopters could no longer be used to transport the remaining people. Therefore, 7 patients and 9 hospital employees were left at Futaba High School. Without adequate medical equipment, the remaining staff continued to provide all possible care to the remaining patients overnight. In the morning of March 13, the patients and hospital employees were finally transported to the Kasuminome Air Field and thereafter, those who were left at the Kasuminome Air Field were transported to Nihonmatsu City by helicopters provided by the JSDF.

POST-EVACUATION SITUATION

Emergency evacuation was carried out in a chaotic manner. Since patients were evacuated separately, the hospital staff temporarily lost track of certain patients. However, the locations and situations of all patients were confirmed on 16 March 2011. The medical staff who accompanied patients helped each other in arranging the destinations of hospital transfer for the patients. Many hospitals in the Tohoku region, including those in Fukushima Prefecture, were affected by the disaster. In such a situation, hospitals in Fukushima Prefecture not only accepted patients from Futaba Kosei Hospital but also those from other hospitals in the evacuation zone. Therefore, it was extremely difficult to arrange hospital transfers. However, through the personal network of physicians of Futaba Kosei Hospital, patients who required hospitalization were accepted by other hospitals within several days.

The evacuation commenced on 12 March 2011. On the same day, 2 patients with end-stage cancer and 1 with a serious condition died. On 13 March 2011, a patient with severe heart failure died. A total of 5 patients (3.7%), including those mentioned above, died within a week of evacuation. According to a survey conducted by Futaba Kosei Hospital, 9 patients (6.6%) died within 1 month of evacuation and 17 (12.5%) died within 3 months of evacuation [23].

DISCUSSION

This study reported the decision-making process for the evacuation of patients as well as the evacuation procedures implemented at Futaba Kosei Hospital, located within 5 km of the FDNPP. The authors express their sincere appreciation to the employees who spared no effort in conducting the evacuation during this extremely difficult and unprecedented emergency. The evacuation of all patients was successfully completed within 24 h of commencement. Despite the difficulty in communicating with the Disaster Task Force, they coordinated with the JSDF for transportation assistance, which contributed to the evacuation and enabled the medical staff to accompany the patients. Nevertheless, 4 patients died during the evacuation. This result suggests that inpatients experience a heavy burden, both physically and mentally, during an evacuation.

The method of emergency hospital evacuation conducted in Futaba Kosei Hospital was a reasonable one and followed the basic approach of hospital evacuation during a nuclear emergency; this could only have been accomplished incidentally as a result of full efforts by the hospital staff. After the nuclear accident at Three Mile Island (TMI), four hospitals within a 20-mile radius from the nuclear power plant evacuated their inpatients, although the severely ill patients were retained in the risk zone [24, 25]. The basic hospital response of inpatient evacuation was divided into five categories based on the hospital’s organizational response during the TMI accident: census reduction, staffing, administrative response, emergency/critical care services, and hospital evacuation and transportation [24]. In terms of this categorization, Futaba Kosei Hospital first evacuated ambulatory inpatients (census reduction), distributed well-assigned staff for necessary care of the severely ill patients (staffing) and gained necessary information from the local disaster task force (administrative response). Since the evacuation of severely ill patients was not implemented during the TMI accident, there was limited practice on the evacuation of severely ill patients during a nuclear emergency before the FDNPP accident. Therefore, the method used to evacuate severely ill patients in Futaba Kosei Hospital, such as evacuation by groups comprising patients, physicians, and other medical staff, and the support provided by the JSDF may be one of the best possible solutions.

With regard to the evacuation of patients from Futaba Kosei Hospital, early intervention by external organizations, such as the JSDF, is particularly notable and may have led to the efficient evacuation of all hospital inpatients. It is likely that communication between the hospital and the Fukushima Disaster Task Force, from the early stage of evacuation, led to an early intervention by the JSDF. In addition, the Disaster Medical Assistance Team and the Japanese Red Cross Society, which were supposed to support emergency activities in disaster-affected areas immediately after a traditional disaster, contributed to the care of patients transported from hospitals within the 20-km radius from the FDNPP after hospital evacuations in temporary evacuation sites, despite not being able to carry out emergency hospital evacuation withins the 20-km radius from the FDNPP due to insufficient information about radiation contamination at that time. Meanwhile, the nearby Futaba Hospital, which was in a similar situation, failed to collaborate with external organizations, resulting in the deaths of many patients. To minimize the burden on inpatients when a nuclear disaster occurs, it is necessary for hospitals in disaster-prone areas to develop a specific method of communication (ideally more than one) beforehand for establishing close communication with organizations that would take the lead during such evacuations.

The physical and mental burden on patients forced to evacuate urgently from the hospital can be enormous. In the area surrounding the FNDPP immediately after the accident, the radiation levels increased markedly, the inflow of materials was cut off, and no one knew the detailed situation at the FDNPP. As a result, the hospitals near the FDNPP had almost no plan for a major nuclear emergency and might have had no other option but to evacuate. Indeed, the efficient evacuation from Futaba Kosei Hospital was miraculously achieved because measures such as early intervention by the JSDF and an innovative evacuation approach were adopted by the hospital management (patients and hospital staff from different professions were assigned groups). However, four hospital inpatients lost their lives during the evacuation despite such an efficient response. Moreover, 12.5% of hospital inpatients died within 3 months of evacuation [23]. If an accident occurs at a nuclear power plant, evacuation from medical institutions located in close proximity to the plant is inevitable. However, in hindsight, the radiation dose following the FDNPP accident did not reach a level that would cause immediate harm to health in most parts of the evacuation zone. In these areas, people might have been safe as long as they stayed inside the building, and the mortality risk from evacuation may have significantly exceeded that from radiation exposure. In fact, at Futaba Hospital, 39 (11.6%) of 338 inpatients died during the emergency evacuation. The efficient evacuation achieved by Futaba Kosei Hospital may have been coincidental. It cannot be guaranteed that hospitals would be able to evacuate patients and staff with similar efficiency if another disaster similar to the FDNPP accident were to occur. Hence, further discussion is needed on the methods of evacuation from medical institutions in the case of a nuclear accident, as medical institutions accommodate many people with compromised health.

In the case of a nuclear accident, it is difficult to secure places for transferring patients who require immediate hospitalization after removal from the evacuation zone. In the case of the FDNPP accident, potential patient transfer destinations had not been considered before the accident occurred. Consequently, although the evacuation of patients from many hospitals was required in disaster-affected areas during the FDNPP accident, hospitals in other areas of the Fukushima Prefecture did not have sufficient capacity to accept these patients as those hospitals were also affected by the earthquake. From this experience, we can learn that signing patient acceptance agreements with neighboring hospitals in the same area may not be effective in the case of a nuclear disaster. This is because not only hospitals in close proximity to the site of the accident but also those in surrounding areas may need to urgently evacuate patients depending on the severity of the accident. In preparation for a nuclear accident, securing evacuation sites in areas that are sufficiently distant from the nuclear plant may be effective.

Lastly, it should also be discussed as to whether the decision to urgently evacuate from hospitals within a 5-km zone of the nuclear power plant, including Futaba Kosei Hospital, was necessary. Within several days following the accident at the FDNPP, all residents living within the 20-km zone of the plant, including those in hospitals and care facilities, evacuated the zone. In other words, all medical facilities within the zone were abandoned in <72 h after the occurrence of the earthquake and tsunami, which is a commonly adopted time limit for rescue operations. The local healthcare system in this area is yet to fully recover from the nuclear power plant accident that occurred 9 years ago. This finding suggests that the decision to evacuate had a significant negative impact on the local healthcare system of Futaba District, where the FDNPP is located. Considerable resources are needed to rebuild the healthcare system in a significantly disrupted disaster-affected area. Further discussion is required on the extent to which the healthcare system needs to be maintained in a disaster-affected area in the case of a nuclear accident, although this extent would depend on the magnitude of the nuclear accident.

It is necessary to determine the kind of preparations and measures that should be implemented in medical institutions located near a nuclear power plant in normal times in order to prepare for an emergency evacuation. The 2009 Fukushima Prefecture Disaster Prevention Plan: Nuclear Accidents, which was issued prior to the FDNPP accident, set forth procedures for evacuation from medical institutions: ‘The managers of medical institutions such as hospitals and clinics shall instruct their employees to help patients evacuate from the building in accordance with the organization’s system, which shall be based on the fire defense plan. If necessary, support should be sought from other institutions, such as hospitals and clinics, for evacuating patients. When helping patients evacuate, evacuation equipment that is appropriate for the condition of the patient should be used. Evacuation shelters must be hospitals or equivalent facilities that are equipped with medical and rescue equipment.’ [26] Notwithstanding this plan, no detailed rules reflecting the specific situation of a local community were formulated. Therefore, the hospitals located in the affected areas experienced great confusion during the FDNPP accident because the scope of the disaster management plan did not include major nuclear emergencies or complex disasters nor the responsibilities of staff in hospitals located in the affected area during patient evacuation. In Japan, in response to the FDNPP accident, the Nuclear Emergency Response Guideline has been revised since 2015 to enhance training and support specific to nuclear emergencies. Although drills under the assumption of a nuclear disaster are being carried out across the country, implementing a safe mass evacuation and transportation in a disaster-affected area immediately after a nuclear emergency remains a challenge. In order to develop effective evacuation plans for hospitals in cases of nuclear accidents, a more multi-faceted, systematic and deeper discussion is needed.

This is one of the few studies that provides a description of the evacuation process of a hospital located within the 5-km zone from the FDNPP. However, this study has a number of limitations. First, it is not clear whether evacuation per se was the direct cause of death in patients who died during and after evacuation. Second, we were unable to access the information that would have shown what kind of scheme was used when an external organization such as the JSDF intervened in the evacuation of Futaba Kosei Hospital, although the hospital had been communicating with the Fukushima Disaster Task Force from the early stage of evacuation. To address these limitations, further research is needed to evaluate the evacuation procedure implemented by various hospitals in the most affected areas during the FDNPP accident.

In conclusion, Futaba Kosei Hospital received support from the JSDF at an early stage of the disaster and completed the temporary evacuation of 136 inpatients within ~24 h of the commencement of evacuation. Through a personal network of physicians, the hospital also secured patient transfer destinations following the evacuation. Although people at the hospital had no other option but to evacuate, the hospital managed to complete the evacuation relatively successfully. However, four patients died during the evacuation. To implement evacuation procedures more efficiently and safely, it may be useful for hospitals to develop an evacuation plan, including the methods of using external resources and the destination of evacuation, in normal times.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

A.O. received financial support from Medical Network Systems, Inc. for purposes unrelated to this work. The authors declare no competing interests with regard to this work.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Radiation Safety Research Promotion Fund on the risk–benefit of protective actions during nuclear emergencies organized by the Nuclear Regulation Authority, Japan.

SUPPLEMENT FUNDING

This supplement has been funded by the Program of the Network-type Joint Usage/Research Center for Radiation Disaster Medical Science of Hiroshima University, Nagasaki University, and Fukushima Medical University.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the staff of Futaba Kosei Hospital, the staff of all the transport facilities for patient care, and the transport personnel involved in the emergency evacuation. The authors also thank Mr Masatsugu Tanaki of Minamisoma Municipal General Hospital for providing technical support. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for providing English language editing assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1. Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 2005;365:1099–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Waisel DB. Vulnerable populations in healthcare. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2013;26:186–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization , Environmental health in emergencies, Vulnerable groups. http: //www.who.int/environmental_health_emergencies/vulnerable_groups/en/ (June 8 2020, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bethel JW, Foreman AN, Burke SC. Disaster preparedness among medically vulnerable populations. Am J Prev Med 2011;40:139–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aldrich N, Benson WF. Disaster preparedness and the chronic disease needs of vulnerable older adults. Prev Chronic Dis 2008;5:A27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cherniack EP. The impact of natural disasters on the elderly. Am J Disaster Med 2008;3:133–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Icenogle M, Eastburn S, Arrieta M. Katrina’s legacy: Processes for patient disaster preparation have improved but important gaps remain. Am J Med Sci 2016;352:455–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brown LM, Dosa DM, Thomas K et al. The effects of evacuation on nursing home residents with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2012;27:406–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dosa DM, Grossman N, Wetle T et al. To evacuate or not to evacuate: Lessons learned from Louisiana nursing home administrators following hurricanes Katrina and Rita. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2007;8:142–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thomas KS, Dosa D, Hyer K et al. Effect of forced transitions on the most functionally impaired nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:1895–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Irisawa A. The 2011 great East Japan earthquake: A report of a regional hospital in Fukushima prefecture coping with the Fukushima nuclear disaster. Dig Endosc 2012;24:3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sawano T, Nishikawa Y, Ozaki A et al. Premature death associated with long-term evacuation among a vulnerable population after the Fukushima nuclear disaster: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e16162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kodama Y, Oikawa T, Hayashi K et al. Impact of natural disaster combined with nuclear power plant accidents on local medical services: A case study of Minamisoma municipal general hospital after the great East Japan earthquake. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2014;8:471–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Okumura T, Tokuno S. Case study of medical evacuation before and after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident in the great East Japan earthquake. Disaster Mil Med 2015;1:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nomura S, Blangiardo M, Tsubokura M et al. Post-nuclear disaster evacuation and survival amongst elderly people in Fukushima: A comparative analysis between evacuees and non-evacuees. Prev Med 2016;82:77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nomura S, Gilmour S, Tsubokura M et al. Mortality risk amongst nursing home residents evacuated after the Fukushima nuclear accident: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One 2013;8:e60192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Murakami M, Ono K, Tsubokura M et al. Was the risk from nursing-home evacuation after the Fukushima accident higher than the radiation risk? PLoS One 2015;10:e0137906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yasumura S, Goto A, Yamazaki S et al. Excess mortality among relocated institutionalized elderly after the Fukushima nuclear disaster. Public Health 2013;127:186–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tanigawa K, Hosoi Y, Terasawa S et al. Lessons learned from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident; the initial 5 days medical activities after the accident. JJAAM 2011;22:782–91. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ohtsuru A, Tanigawa K, Kumagai A et al. Nuclear disasters and health: Lessons learned, challenges, and proposals. Lancet 2015;386:489–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. International Atomic Energy Agency . The Fukushima Daiichi Accident. Technical Volume 3/5. In: Emergency Preparedness and Response. Vienna: International Atomic Energy Agency, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tsujiguchi T. The transition of nuclear disaster medical system in Japan; the change after Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident and the activities of Hirosaki University. Biomed J Sci & Tech Res 2018;8:6470–2. [Google Scholar]

- 23. JA Fukushima Kouseiren Records of the Great East Japan Earthquake and the Nuclear Power Plant Accident . “Futaba, Kashima, and the Future”. Keiichi Morita (ed.). In Japanese: Fukushima Agricultural Cooperatives, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maxwell C. Hospital organizational response to the nuclear accident at three Mile Island: Implications for future-oriented disaster planning. Am J Public Health 1982;72:275–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smith JS Jr, Fisher JH. Three Mile Island. The silent disaster JAMA 1981;245:1656–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fukushima Prefecture Disaster Prevention Plan . Nuclear Accidents (amended in FY 2009). Fukushima: Fukushima Prefecture, 2009, (In Japanese). [Google Scholar]