ABSTRACT

The Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station (NPS) accident, which occurred in March 2011, is having long-term effects on children. About 3 years after the accident, we identified three patterns of peer relationship problems and four patterns of emotional symptoms using group-based trajectory modeling. As a result, we reported that different factors might be related to very severe trajectories of peer relationship problems and emotional symptoms. In this study, we used five waves of data from fiscal year (FY) 2011 to FY2015 from the Mental Health and Lifestyle Survey, a detailed survey of the Fukushima Health Management Survey started in FY2011. We analyzed 7013 residents within the government-designated evacuation zone (aged 6–12 years old as of 11 March 2011) with responses to all items of psychological distress in at least one wave from FY2011 and FY2015. We planned this study to describe the trajectories of peer relationship problems and emotional symptoms in children and to examine potential risks and protective factors over the 5 years following the NPS accident. We identified four patterns of peer relationship problems and five patterns of emotional symptoms using latent class growth analysis. For peer relationship problems, male sex, experiencing the NPS explosion and lack of exercise habits were associated with the severe trajectory group. For emotional symptoms, experiencing the NPS explosion, experiencing the tsunami disaster and lack of exercise habits were associated with the severe trajectory group. Exercise habits are very important for the mental health of evacuees after a nuclear disaster.

Keywords: nuclear power station accident, child and adolescent psychiatry, Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire, trajectory analysis, exercise habits

INTRODUCTION

Peer relationships and emotional symptoms are important factors for mental health in adolescents. A meta-analysis linking parent–child and peer relationship quality to empathy in adolescence indicated that adolescents with higher-quality peer relationships tend to show more concern for and understanding of others’ emotions than adolescents with lower-quality relationships [1]. Increases in the quality of peer relationships were strongly associated with declines in post-traumatic stress (PTS) symptoms [2]. Lai et al. also reported that social support from parents, teachers and peers showed a statistically significant effect on PTS symptoms after a natural disaster [3].

Epidemiological analysis in Danish people showed that female sex, low occupational social class, single parent family, exposure to bullying and a high prevalence of bullying at school are all associated with emotional symptoms [4]. After a natural disaster, children showed abnormal ranges on the Emotional Symptoms subscale of the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [5].

The Great East Japan Earthquake (GEJE) and subsequent nuclear accident at Tokyo Electric Power Company’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station (NPS), which occurred in 2011, have caused longitudinal effects on the lives of residents of Fukushima Prefecture, including children. Usami et al. reported that the traumatic symptoms of children improved 20 months after the disaster [6], but that the rates of children with difficulties remained high even 30 months after the disaster [7]. Fujiwara et al. reported that one in four children still had behavior problems, including internalizing and externalizing problems, even 2 years after the GEJE [8].

A recent systematic review showed that mental health problems seemed to be more severe in residents of Fukushima than in those in other affected areas [9]. We previously described the longitudinal trajectories of peer relationship problems and emotional symptoms over the 35 months following the NPS accident, and examined the potential risks and protective factors [10]. In our previous study, we identified three patterns of peer relationship problems and four patterns of emotional symptoms using group-based trajectory modeling. For peer relationship problems, male sex, experiencing the NPS explosion and insufficient physical activity were associated with a very severe trajectory. In contrast, for emotional symptoms, female sex, experiencing the tsunami and NPS explosion, out-of-prefecture evacuation and insufficient physical activity were associated with a very severe trajectory. In addition, our previous study showed that those with low exercise habits were also at high risk of pediatric mental health problems [11]. Different factors might be related to very severe trajectories of peer relationship problems and emotional symptoms. Our previous analysis was for the first 3 years after the earthquake. Therefore, in the present study, we conducted an additional trial trajectory analysis over the 5 years following the earthquake and confirmed changes in the tendencies of peer relationship problems and emotional symptoms. A previous study clarified that hyperactivity/inattention symptom decreases with growth [12]. Therefore, these items were not included in the present study, which aimed to track and study the effects after a disaster over time. We instead paid particular attention to the mental health of children after the earthquake using the SDQ peer relationship problems subscale (SDQ-peer) and the emotional symptoms subscale (SDQ-emotional), and also included environmental factors after the nuclear accident.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

STUDY POPULATION

The Mental Health and Lifestyle Survey was implemented as part of the Fukushima Health Management Survey. This survey aims to monitor the mental health status of evacuees of the NPS accident [13]. This study was designed as a cohort study at five time points. The target population was 11 791 children born after 2 April 1998 and before 1 April 2004 who were elementary school students (i.e. in the first to the sixth grade) on 11 March 2011, and living in one of the 13 target municipalities of the Mental Health and Lifestyle Survey. The target zone included Hirono, Naraha, Tomioka, Kawauchi, Okuma, Futaba, Namie, Katsurao, Iitate, Minamisoma, Tamura, Kawamata and hot-spot (places associated with high levels of radiation) areas in Date. The fiscal year (FY) in Japan begins on 1 April and ends on 31 March. The assessments in FY2011 to FY2015 were each held in January of the subsequent year. These assessments were conducted by mail, 10, 22, 35, 47 and 59 months after the disaster. Caregivers of the children completed the questionnaire. All study participants (i.e. parents of the target children) gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. Reminders were sent once to the parents for each assessment. The number of individuals who responded at least once to any of the five assessments was 7013. Outcome response rates for peer relationship problems (n = 6982) were 88% in 2011, 55% in 2012, 47% in 2013, 33% in 2014 and 31% in 2015. Outcome response rates for emotional symptoms (n = 6981) were 88% in 2011, 55% in 2012, 47% in 2013, 33% in 2014 and 32% in 2015. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Fukushima Medical University (No. 1316, No. 2148).

ASSESSMENTS

Disaster experience was categorized as experiencing the tsunami and experiencing the explosion at the NPS. Experiencing the NPS explosion was defined as the parents hearing sounds of the NPS explosion. Emotional symptoms and peer relationship problems were assessed using 10 items of the SDQ [14–16]. The SDQ is a 25-item questionnaire used to identify psychopathological problems in children. Each item is scored 0, 1 or 2, and each subscale score ranges from 0 to 10. The Japanese version of the SDQ has shown adequate internal consistency (α = 0.81) [17, 18] and convergent validity [18]. As it may reflect the mental health problems of children after the disaster, we used SDQ-peer and SDQ-emotional for this study [1–5]. The same factors affecting peer relationships and emotional symptoms were selected from our previous study [10]. Exercise habits were evaluated with the question, ‘How frequently does your child exercise, excluding physical education class for elementary and middle school children?’ There were four response options: almost every day; 2–4 times a week; once a week; and seldom or never. Questions about sociodemographic characteristics and disaster-related variables were also included.

DATA ANALYSIS

Trajectory analysis allows for classification of items into several patterns to analyze changes over time. Therefore, trajectory analysis was conducted to examine patterns in the trajectories of peer relationship problems and emotional symptoms. The estimated mean trajectories of SDQ-peer and SDQ-emotional were examined by applying latent class growth analysis (LCGA) to the total score of SDQ for each year from FY2011 to FY2015. Trajectories were determined based on lower scores represent better fitting. Missing data were handled as missing by full information maximum likelihood estimation.

The distributions of both SDQ-peer and SDQ-emotional showed a strong positive skew and the scores were concentrated at zero. Therefore, we selected a zero-excess Poisson distribution for LCGA. As a result, peer relationship problems comprised four classes and emotional symptoms comprised five classes. A small class number was defined as a severe trajectory. Therefore, subjects with a class number of 1 were defined as the severe trajectory group, and those with a class number >1 were defined as the not severe trajectory group. After defining the trajectory, sex, age, disaster experience, place of residence and exercise habits were investigated exploratively. We conducted multinomial logistic regression analysis to examine which class was likely to belong to each factor. We used Mplus version 8 [19] to conduct LCGA, the nnet package [20] in R [21] to conduct multinomial logistic regression, and all other descriptive analyses were conducted on R base functions.

RESULTS

SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS AND DISASTER-RELATED VARIABLES

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the study subjects. The subjects were 7013 children who had responded to the Mental Health and Lifestyle Survey at least once from FY2011 to FY2015 and were 6–12 years old at the time of the earthquake. This is about 1300 fewer subjects than our previous report from FY2011 to FY2013 [10]. Among the children analyzed, 11.5% had experienced the tsunami and 38.8% had experienced the NPS explosion. In total 29.9% of the children were living outside of Fukushima Prefecture in 2011. The ratio of subjects with disaster experience was similar to our previous report [10].

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study subjects

| Sex | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Male | 3603 (51.4) |

| Female | 3410 (48.6) |

| Age (years) | |

| 6 | 1372 (19.6) |

| 7 | 1369 (19.5) |

| 8 | 1396 (19.9) |

| 9 | 1452 (20.7) |

| 10 | 1424 (20.3) |

| Disaster experience | |

| Tsunami | 719 (11.5) |

| NPS explosion | 2434 (38.8) |

| Missing data | 745 |

| Place of residence in 2011 | |

| Fukushima Prefecture | 4364 (70.1) |

| Outside of Fukushima Prefecture | 1863 (29.9) |

| Missing data | 786 |

| Exercise habits in 2011 | |

| Almost every day | 210 (4.2) |

| 2–4 times a week | 1024 (20.3) |

| Once a week | 857 (17.0) |

| Seldom or never | 2965 (58.6) |

| Missing data | 1957 |

TRAJECTORIES OF EMOTIONAL PEER RELATIONSHIP PROBLEMS AND EMOTIONAL SYMPTOMS

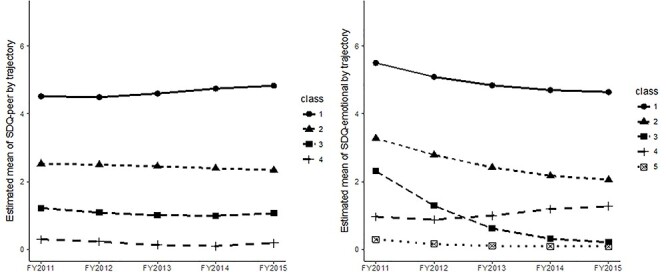

Figure 1 shows the estimated mean trajectories of SDQ-peer relationship problems and SDQ-emotional symptoms based on LCGA. A class number of 1 was defined as very severe; the larger the number the less severe the problem. Comparing goodness-of-fit for models with different numbers of trajectories of peer relationship problems over time, a four-trajectory model was found to have the best fit. Comparing goodness-of-fit for models with different numbers of trajectories of emotional symptoms over time, a five-trajectory model was found to have the best fit.

Fig. 1.

Estimated mean trajectories for SDQ-peer (left) and SDQ-emotional (right) based on LCGA.

From FY2011 to FY2015, the trajectories of all classes of estimated mean SDQ-peer relationship problems followed a parallel line. On the other hand, SDQ-emotional problems showed a decreasing trend in classes 1–3, which had high scores after the earthquake. These trends were similar to those in our previous report [10]. To check for response bias, the SDQ-peer relationship problems score and SDQ-emotional symptoms score of the FY2011 survey were compared between the group that responded at least once after FY2012 and the group that did not respond at all. The results showed no difference in SDQ scores between the groups in either SDQ-peer relationship problems (responded at least once = 2.16, no response = 2.10 (t-test, P = 0.20)) or SDQ-emotional problems (responded at least once = 2.60, no response =2.61 (t-test, P = 0.90)).

DISTRIBUTIONS OF SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC VARIABLES OF PEER RELATIONSHIP PROBLEMS AND EMOTIONAL SYMPTOMS

Tables 2 and 3 show the distributions of sociodemographic variables of peer relationship problems and emotional symptoms latent class based on LCGA. The sociodemographic characteristics of sex, exercise habits and experiencing the NPS explosion showed significant differences in trajectory groups for peer relationship problems (Table 2). On the other hand, place of residence, exercise habits, experiencing the tsunami and experiencing the NPS explosion showed significant differences in trajectory groups only for emotional symptoms (Table 3).

Table 2.

Distributions of sociodemographic variables by latent class of peer relationship problems based on LCGA.

| Estimated latent class: peer relationship problems | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | P | |

| 639 (9.2) | 3232 (46.3) | 2787 (39.9) | 323 (4.6) | ||

| Age at time of disaster (years) | 0.568 | ||||

| 6 | 118 (18.5) | 659 (20.4) | 529 (19.0) | 60 (18.6) | |

| 7 | 126 (19.7) | 625 (19.3) | 548 (19.7) | 63 (19.5) | |

| 8 | 110 (17.2) | 651 (20.1) | 553 (19.8) | 76 (23.5) | |

| 9 | 143 (22.4) | 651 (20.1) | 585 (21.0) | 66 (20.4) | |

| 10 | 142 (22.2) | 646 (20.0) | 572 (20.5) | 58 (18.0) | |

| Place of residence in 2011 | |||||

| Outside of Fukushima Prefecture | 166 (29.7) | 811 (28.6) | 773 (30.8) | 106 (34.8) | 0.081 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 253 (39.6) | 1598 (49.4) | 1391 (49.9) | 154 (47.7) | <0.001 |

| Exercise habits | <0.001 | ||||

| Almost every day | 12 (2.6) | 81 (3.6) | 105 (5.1) | 12 (4.8) | |

| 2–4 times a week | 70 (15.0) | 405 (17.8) | 482 (23.6) | 65 (25.9) | |

| Once a week | 78 (16.7) | 358 (15.7) | 367 (18.0) | 51 (20.3) | |

| Seldom or never | 306 (65.7) | 1437 (63.0) | 1086 (53.2) | 123 (49.0) | |

| Disaster experience | |||||

| Tsunami | 67 (11.9) | 322 (11.3) | 292 (11.6) | 33 (10.8) | 0.956 |

| NPS explosion (%) | 251 (44.4) | 1126 (39.5) | 945 (37.5) | 101 (33.1) | 0.003 |

Table 3.

Distribution of sociodemographic variables by latent class of emotional symptoms based on LCGA.

| Estimated latent class: emotional symptoms | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | P | |

| 1115 (16.0) | 2607 (37.3) | 465 (6.7) | 1398 (20.0) | 1397 (20.0) | ||

| Age at time of disaster (years) | 0.10 | |||||

| 6 | 222 (19.9) | 526 (20.2) | 90 (19.4) | 289 (20.7) | 237 (17.0) | |

| 7 | 237 (21.3) | 512 (19.6) | 102 (21.9) | 253 (18.1) | 258 (18.5) | |

| 8 | 225 (20.2) | 510 (19.6) | 97 (20.9) | 267 (19.1) | 290 (20.8) | |

| 9 | 227 (20.4) | 529 (20.3) | 99 (21.3) | 282 (20.2) | 309 (22.1) | |

| 10 | 204 (18.3) | 530 (20.3) | 77 (16.6) | 307 (22.0) | 303 (21.7) | |

| Place of residence in 2011 | ||||||

| Outside of Fukushima Prefecture | 334 (33.8) | 715 (30.7) | 124 (28.0) | 355 (27.9) | 327 (27.9) | 0.01 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 575 (51.6) | 1293 (49.6) | 219 (47.1) | 657 (47.0) | 653 (46.7) | 0.068 |

| Exercise habits | <0.001 | |||||

| Almost every day | 23 (2.9) | 61 (3.2) | 13 (3.6) | 53 (5.2) | 59 (6.1) | |

| 2–4 times a week | 120 (15.1) | 382 (20.2) | 68 (18.7) | 216 (21.3) | 236 (24.3) | |

| Once a week | 117 (14.7) | 327 (17.3) | 61 (16.8) | 177 (17.4) | 173 (17.8) | |

| Seldom or never | 535 (67.3) | 1125 (59.4) | 221 (60.9) | 569 (56.1) | 504 (51.9) | |

| Disaster experience | ||||||

| Tsunami | 132 (13.3) | 288 (12.3) | 55 (12.4) | 136 (10.6) | 105 (8.9) | 0.007 |

| NPS explosion | 465 (46.9) | 927 (39.5) | 171 (38.4) | 473 (37.0) | 393 (33.1) | <0.001 |

MULTINOMIAL LOGISTIC REGRESSION ANALYSIS

To explore which class was more likely to belong to each factor, multinomial logistic regression analysis was performed for each of peer relationship problems and emotional symptoms using class 4 as a reference (Table 4). Notable results were shown in bolt font. For class 1 vs 4 (5 for emotional symptoms), subjects who had experienced the NPS explosion (peer relationship problems: odds ratio [OR] 1.695 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.219–2.357); emotional symptoms: OR 1.710 (95%CI: 1.404–2.084)) and had a lack of exercise (peer relationship problems: OR 2.054 (95%CI: 1.498–2.815), emotional symptoms: OR 1.875 (95%CI: 1.540–2.283)) were more likely to have peer relationship problems and emotional symptoms. Males were more likely to have peer relationship problems (OR 0.713 (95%CI: 0.522–0.975)). Those who had experienced the tsunami were more likely to have emotional symptoms (OR 1.494 (95%CI: 1.101–2.026)). For class 2 vs 4 (5 for emotional symptoms), subjects who had experienced the NPS explosion (peer relationship problems: OR 1.425 (95%CI: 1.072–1.894); emotional symptoms: 1.281 (95%CI: 1.086–1.512)) and had a lack of exercise (peer relationship problems: OR 1.761 (95%CI: 1.353–2.292); emotional symptoms: OR 1.349 (95%CI: 1.153–1.578)) were also more likely to have peer relationship problems and emotional symptoms. Subjects living outside of Fukushima Prefecture were less likely to have peer relationship problems (OR 0.751 (95%CI: 0.567–0.997)). Those who had experienced the tsunami were more likely to have emotional symptoms (OR 1.368 (95%CI: 1.050–1.783)). For class 3 vs 4 (5 for emotional symptoms), those who had experienced the tsunami (OR 1.570 (95%CI: 1.075–2.295)) and had a lack of exercise (OR 1.435 (95%CI: 1.121–1.837)) were more likely to have emotional symptoms.

Table 4.

Multinomial logistic regression (class 4 as reference)

| Class | Predictor | OR (95%CI) for peer relationship problems | OR (95%CI) for emotional symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 vs 4 (5 for emotional symptoms) | |||

| Female | 0.713 (0.522–0.975) | 1.157 (0.956–1.401) | |

| Age at time of disaster <10 years | 0.708 (0.490–1.022) | 1.132 (0.905–1.415) | |

| Experiencing the tsunami disaster | 1.132 (0.683–1.875) | 1.494 (1.101–2.026) | |

| Experiencing the NPS explosion | 1.695 (1.219–2.357) | 1.710 (1.404–2.084) | |

| Place of residence in 2011 | |||

| Outside of Fukushima Prefecture | 0.781 (0.559–1.093) | 1.213 (0.984–1.494) | |

| Lack of exercise | 2.054 (1.498–2.815) | 1.875 (1.540–2.283) | |

| Class 2 vs 4 (5 for emotional symptoms) | |||

| Female | 1.055 (0.811–1.374) | 1.059 (0.906–1.238) | |

| Age at time of disaster <10 years | 0.800 (0.581–1.100) | 0.995 (0.831–1.190) | |

| Experiencing the tsunami disaster | 1.102 (0.711–1.709) | 1.368 (1.050–1.783) | |

| Experiencing the NPS explosion | 1.425 (1.072–1.894) | 1.281 (1.086–1.512) | |

| Place of residence in 2011 | |||

| Outside of Fukushima Prefecture | 0.751 (0.567–0.997) | 1.111 (0.933–1.322) | |

| Lack of exercise | 1.761 (1.353–2.292) | 1.349 (1.153–1.578) | |

| Class 3 vs 4 (5 for emotional symptoms) | |||

| Female | 1.054 (0.809–1.373) | 0.958 (0.751–1.222) | |

| Age at time of disaster <10 years | 0.825 (0.599–1.136) | 1.320 (0.982–1.774) | |

| Experiencing the tsunami | 1.130 (0.728–1.755) | 1.570 (1.075–2.295) | |

| Experiencing the NPS explosion | 1.315 (0.988–1.750) | 1.206 (0.934–1.556) | |

| Place of residence in 2011 | |||

| Outside of Fukushima Prefecture | 0.853 (0.643–1.131) | 0.945 (0.718–1.243) | |

| Lack of exercise | 1.182 (0.908–1.540) | 1.435 (1.121–1.837) | |

| Class 4 vs 5 | |||

| Female | 1.001 (0.838–1.195) | ||

| Age at time of disaster <10 years | - | 0.856 (0.701–1.046) | |

| Experiencing the tsunami disaster | - | 1.180 (0.871–1.598) | |

| Experiencing the NPS explosion | - | 1.131 (0.937–1.365) | |

| Place of residence in 2011 | |||

| Outside of Fukushima Prefecture | - | 0.995 (0.815–1.215) | |

| Lack of exercise | - | 1.188 (0.994–1.419) | |

DISCUSSION

We conducted this study to describe the trajectories of peer relationship problems and emotional symptoms in children and to examine the potential risks and protective factors over the 5 years following the NPS accident as an extension of our previous 3-year trajectory study [10]. The number of subjects was reduced by ~1300. However, the rate of children’s disaster experience was similar to our previous report [10].

We identified four patterns of peer relationship problems and five patterns of emotional symptoms, using LCGA. From FY2011 to FY2015, the trajectories of all classes of estimated mean SDQ-peer relationship problems followed parallel lines despite our previous study showing a slight decrease in the very severe trajectory group between 2011 and 2012 assessments [10]. This may indicate that the number of trajectories increased from three to four and that we cannot be optimistic about the course of peer relationship problems. Following the same tendency as the previous report [10], this study score remained higher than the mean score for peer problems based on parent ratings of the Japanese normative population sample (1.44–1.52) [18]. Peer relationship problems may remain severe psychological problems in the children in our study. Because there is a possibility that peer relationship problems may reflect a preference for solitude and could be associated with adjustment difficulties, it is necessary to monitor these children carefully in the future [22, 23]. On the other hand, SDQ-emotional problems showed a decreasing trend in classes 1–3, which was 60% of the target subjects. These trends were similar to our previous report [10], with a decreasing trajectory suggesting that the emotional symptoms of the target subjects are improving. The mean trajectories of SDQ-emotional problems showed a conversion of classes 3 and 4 (Figure 1). As more children in class 3 experienced the tsunami but not the NPP explosion (Table 4), it could be said that experiencing the tsunami may have caused a deterioration in their mental status even several years after the disaster.

According to the distributions of sociodemographic variables of SDQ-peer relationship problems and SDQ-emotional symptoms latent class based on LCGA, we found that exercise habits and experiencing the NPS explosion showed significant differences in trajectory groups for both peer relationship problems and emotional symptoms. This result was consistent with our previous report showing that exercise habits were the most important factor for maintaining children’s mental health after the disaster [11]. In addition, the proportion of males with a severe trajectory for peer relationship problems was higher than that of females. This tendency is in line with normative data collected among school-aged children in several countries [18, 24, 25].

For SDQ-peer relationship problems in the third and fifth year surveys, using logistic analysis, the most severe trajectories were related to being male, experiencing the NPS explosion and lack of exercise [10]. For SDQ-emotional symptoms, the most severe trajectories in the third year survey were related to being female, experiencing the tsunami, experiencing the NPS explosion, out-of-prefecture residence and lack of exercise; however, in the fifth year survey, these were experiencing the tsunami, experiencing the NPS explosion and lack of exercise [10]. Multinomial logistic regression analysis showed that children who seldom or never exercised in 2011 and experienced the NPS explosion and tsunami were more likely to have peer relationship problems and emotional symptoms. Actually experiencing the NPS explosion and tsunami may have caused both peer relationship problems and emotional symptoms. Although we lacked information on the children’s Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptoms in this survey, it was necessary to consider the possibility that those symptoms were due to PTSD. McDermott et al. reported that SDQ demonstrated different individual risk from PTSD symptoms after a wildfire [5]. Usami et al. also found that SDQ scores and PTSD symptoms showed a significantly low correlation after the GEJE [26]. Therefore, it was speculated that PTSD symptoms were not associated with the present study results.

As in our previous study, low exercise habits were also a high risk for mental health problems [11]. Buchanan and Keats reported that exercise is one of the most useful coping strategies after trauma and disaster events [27]. Carter et al. reported that regular exercise could improve the health status of children [28]. Cao et al. reported that vigorous physical activity was a protective factor for mental illness in adolescents [29]. However, as shown in Table 1, only 4.2% of the study subjects exercised almost every day, whereas 17% exercised once a week and 58.6% exercised very little. Therefore, it is necessary to inform evacuees early that exercise habits are important for the mental health of children based on information acquired after the Fukushima NPS accident.

As for the limitations of this study, the questionnaire was completed by caregivers, which may be less reliable than face-to-face interviews. Several question items in the SDQ used in the present study were slightly different between the first survey year and other years because a revised version of the SDQ was introduced. However, there were no changes to the SDQ-peer relationship problems and SDQ-emotional symptoms subscales. Therefore, we did not think that further analysis regarding other subscales could be conducted in the same manner. It has been demonstrated that among the SDQ subscales, the peer problems subscale has lower internal consistency values for both parent and teacher ratings than other subscales [30]. In this study, age-related factors could not be analyzed due to the small number of subjects. The response rate of the Mental Health and Lifestyle Survey may be decreasing year by year. In particular, the response rate dropped from ~60% in FY2011 to ~30% in FY2015 [31]. It may be hard to say that the subjects analyzed are representative of all children after the NPS accident.

In this study, we described the trajectories of peer relationship problems and emotional symptoms in children and examined potential risks and protective factors over the 5 years following the NPS accident. We found that exercise habits and experiencing the NPS disaster were significantly different between trajectory groups for both peer relationship problems and emotional symptoms. Because experiencing the tsunami disaster and NPS explosion may cause serious problems with peer relationships and emotional symptoms in children, we need to care for victims carefully. More importantly, those with a lack of exercise were at high risk of mental health problems after the disaster. Therefore, it is necessary to inform evacuees that exercise habits are important for the mental health of children after a disaster. It will be necessary to conduct further research in the future to confirm the results.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank all the members of the Fukushima Health Management Survey, especially the mental health group members, for their data collection and suggestions. The findings and conclusions of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the Fukushima Prefectural Government.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the national ‘Health Fund for Children and Adults Affected by the Nuclear Incident’.

SUPPLEMENT FUNDING

This supplement has been funded by the Program of the Network-type Joint Usage/Research Center for Radiation Disaster Medical Science of Hiroshima University, Nagasaki University, and Fukushima Medical University.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Boele S, Van der Graaff J, Wied M et al. Linking parent-child and peer relationship quality to empathy in adolescence: A multilevel meta-analysis. J Youth Adolesc 2019;48:1033–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mishra AA, Christ SL, Schwab-Reese LM et al. Post-traumatic stress symptom development as a function of changing witnessing in-home violence and changing peer relationship quality: Evaluating protective effects of peer relationship quality. Child Abuse Negl 2018;81:332–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lai BS, Osborne MC, Piscitello J et al. The relationship between social support and posttraumatic stress symptoms among youth exposed to a natural disaster. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2018;9:1450042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meilstrup C, Ersbøll AK, Nielsen L et al. Emotional symptoms among adolescents: Epidemiological analysis of individual-classroom- and school-level factors. Eur J Public Health 2015;25:644–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McDermott BM, Lee EM, Judd M et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and general psychopathology in children and adolescents following a wildfire disaster. Can J Psychiatry 2005;50:137–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Usami M, Iwadare Y, Watanabe K et al. Analysis of changes in traumatic symptoms and daily life activity of children affected by the 2011 Japan earthquake and tsunami over time. PLoS One 2014;9:e88885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Usami M, Iwadare Y, Watanabe K et al. Prosocial behaviors during school activities among child survivors after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan: A retrospective observational study. PLoS One 2014;9:e113709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fujiwara T, Yagi J, Homma H et al. Great East Japan earthquake follow-up for children study team. Clinically significant behavior problems among young children 2 years after the great East Japan earthquake. PLoS One 2014;9:e109342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ando S, Kuwabara H, Araki T et al. Mental health problems in a community after the great East Japan earthquake in 2011: A systematic review. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2017;25:15–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Oe M, Maeda M, Ohira T et al. Trajectories of emotional symptoms and peer relationship problems in children after nuclear disaster: Evidence from the Fukushima health management survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:1.pii:E82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Itagaki S, Harigane M, Maeda M et al. Exercise habits are important for the mental health of children in Fukushima after the Fukushima daiichi disaster: The Fukushima health management survey. Asia Pac J Public Health 2017;29:171S–81S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV. Age-dependent decline of symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Impact of remission definition and symptom type. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:816–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yasumura S, Hosoya M, Yamashita S et al. Fukushima health management survey group. Study protocol for the Fukushima health management survey. J Epidemiol 2012;22:375–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goodman R. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1997;38:581–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goodman R. The extended version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire as a guide to child psychiatric caseness and consequent burden. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1999;40:791–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goodman R, Meltzer H, Bailey V. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998;7:125–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Matsuishi T, Nagano M, Araki Y et al. Scale properties of the Japanese version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ): A study of infant and school children in community samples. Brain Dev 2008;30:410–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moriwaki A, Kamio Y. Normative data and psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire among Japanese school-aged children. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2014; 8: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide, Eighth edn. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén, 2017. https://www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/MplusUserGuideVer_8.pdf (28 August 2020, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 20. Venables WN, Ripley BD. Modern Applied Statistics with S, Fourth edn. New York: Springer, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21. R Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2019; https://www.R-project.org/. (28 August 2020, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 22. Caci H, Morin AJ. Investigation of a bifactor model of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015;10:1291–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang JM, Rubin KH, Laursen B et al. Preference-for-solitude and adjustment difficulties in early and late adolescence. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2013;42:834–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tobia V, Marzocchi GM. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire-parents for Italian school-aged children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2017;49:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Koskelainen M. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire among finnish school-aged children and adolescents. Turku, Finland: Painosalama Oy, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Usami M, Iwadate Y, Kodaira M et al. Did parents and teachers struggle with child survivors 20 months after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan? A retrospective observational study. PLoS One 2014;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Buchanan M, Keats P. Coping with traumatic stress in journalism: A critical ethnographic study. Int J Psychol 2011;46:127–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Carter T, Callaghan P, Khalil E et al. The effectiveness of a preferred intensity exercise programme on the mental health outcomes of young people with depression: A sequential mixed methods evaluation. BMC Public Health 2012;12:187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cao H, Qian Q, Weng T. Screen time, physical activity and mental health among urban adolescents in China. Prev Med 2011;53:316–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stone LL, Otten R, Engels RC et al. Psychometric properties of the parent and teacher versions of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire for 4- to 12-year-olds: A review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2010;13:254–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fukushima Medical University . The Mental health and lifestyle survey results report 2015. Fukushima, Japan: Fukushima Prefectural Govement, 2019; https://www.pref.fukushima.lg.jp/uploaded/attachment/335170.pdf (in Japanese) (28 August 2020, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]