Abstract

Family caregivers play an integral role in supporting patient self-management, yet how they perform this role is unclear. We conducted a qualitative metasynthesis of family caregivers’ processes to support patient self-management of chronic, life-limiting illness and factors affecting their support. Methods included a systematic literature search, quality appraisal of articles, data abstraction, and data synthesis to produce novel themes. Thirty articles met inclusion criteria, representing 935 international family caregivers aged 18 to 89 years caring for patients with various health conditions. Three themes characterized family caregivers’ processes to support patient self-management: “Focusing on the Patient’s Illness Needs,” “Activating Resources to Support Oneself as the Family Caregiver,” and “Supporting a Patient Living with a Chronic, Life-Limiting Illness.” Factors affecting family caregivers’ support included Personal Characteristics, Health Status, Resources, Environmental Characteristics, and the Health Care System. The family caregiver role in supporting patient self-management is multidimensional, encompassing three processes of care and influenced by multiple factors.

Keywords: self-management, family caregiver, life-limiting, chronic illness, metasynthesis, qualitative

Self-management is defined as patients’ daily activities to manage symptoms, treatments, lifestyle changes, and the psychosocial, cultural, and spiritual consequences of illness (Richard & Shea, 2011). Use of optimal self-management strategies can help maximize quality of life (Barlow et al., 2002). Per a 2012 metasynthesis (Schulman-Green et al., 2012), patient self-management activities cluster into three main processes, Focusing on Illness Needs, Activating Resources, and Living with a Chronic Illness, each of which includes tasks and skills that facilitate patient self-management. Examples of tasks and skills are learning about the health condition and treatment options, communicating effectively with clinicians, managing emotions, developing self-efficacy, and using health care resources appropriately (Schulman-Green et al., 2012). Per a 2016 metasynthesis (Schulman-Green et al., 2016), factors affecting patients’ self-management include the patient’s personal and lifestyle characteristics, health status, and resources, as well as environmental characteristics and the health care system.

When family members are integrally involved in patients’ processes to manage illness, “self-management” is more accurately referred to as “self- and family management,” reflecting that patients manage their illness with daily assistance from family caregivers and underscoring the dyadic nature of illness management (Grey et al., 2006). This relationship was depicted in the original Self- and Family Management Framework, which illustrates self- and family management as a means of influencing health status, individual and family outcomes, and environmental context (Grey et al., 2006). The original Self- and Family Management Framework, which was refined based on the above-mentioned metasyntheses of patient processes and factors affecting self-management (Schulman-Green et al., 2012, 2016), recognized family caregivers’ involvement in patient self-management (Grey et al., 2006); however, there has been no parallel synthesis and integration of research reflecting family caregivers’ involvement. The processes family caregivers perform to support patient self-management represent a distinct but understudied component of the framework.

Family caregivers’ support of patients with chronic, life-limiting illness includes difficult, life-altering, and often long-term tasks. Caring for these patients may include management of multiple health domains, such as physical and psychological symptom management, discussions of advance care planning, as well as social and financial support (Institute of Medicine, 2015). Contemporary reviews have identified effective interventions to support family involvement in the care and management of patients living with chronic illness (Corry et al., 2015; Whitehead et al., 2018); however, these reviews have not focused on family caregivers of patients managing conditions that are chronic and life-limiting, a population that poses specific caregiving challenges and needs.

Our purpose was to synthesize qualitative data on family caregivers’ processes to support patient self-management of chronic, life-limiting illness and factors affecting their support. Findings will inform future work to enhance the Self- and Family Management Framework by integrating newly identified family caregiver support roles so the Framework more specifically reflects dyadic collaboration. The Framework will then be of greater use in identifying targets for intervention that enhance self- and family management and quality of life for patients with chronic, life-limiting illness and their family caregivers.

Method

This study was a qualitative metasynthesis, an interpretive integration of qualitative findings from primary research reports (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2007), reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009; Shamseer et al., 2015; see Supplemental File 1). The metasynthesis consisted of four sequential steps: a systematic literature search, quality appraisal of identified articles, data abstraction, and interpretive synthesis of data within and across studies to produce novel themes. Although this work did not involve human participants, we conducted this metasynthesis as part of a larger project which had Institutional Review Board approval from Yale University and Duke University.

Search Methods

A medical librarian (J.B.) performed a comprehensive search of MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Embase, CINAHL, and Academic Search Premier. To identify appropriate search terms, the librarian conducted a Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) analysis of articles on family caregiving provided by team members. Relevant controlled vocabulary terms and synonymous free text words and phrases captured the concepts of caregiver, self-management, chronic illness, and life-limiting illness. Four authors (S.L.F., J.N.D.-O., D.S.-G., and R.W.) reviewed the first 100 articles derived from the first round of search results to refine search criteria and inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria were articles written in English and containing family caregiver reports of their processes to support self-management among adult patients (≥18 years old) with chronic, life-limiting illness. The title or abstract had to include the term “self-management” or “self-care.” We defined family caregivers as family members or friends who provide care to a patient with a chronic, life-limiting illness. Studies that included single or multiple family caregivers were included. We defined chronic, life-limiting illness as an illness that is advanced and/or appropriate for palliative care. This definition included single or multiple chronic conditions that contribute to declining function and a poor prognosis for full recovery (Coalition to Transform Advanced Care, 2015). Studies reporting family caregiver, patient, and/or clinician data were included if each data set was distinct. Qualitative results of mixed methods studies were included when qualitative and quantitative data could be distinguished. Excluded studies were those that focused on family caregivers caring for patients with mental illness, substance abuse, and disabilities unrelated to a chronic, life-limiting illness. We also excluded metasyntheses, literature reviews, theory-based works, secondary analyses of data, evaluations of self-management interventions, nondata-based works, and dissertations.

Search Outcome

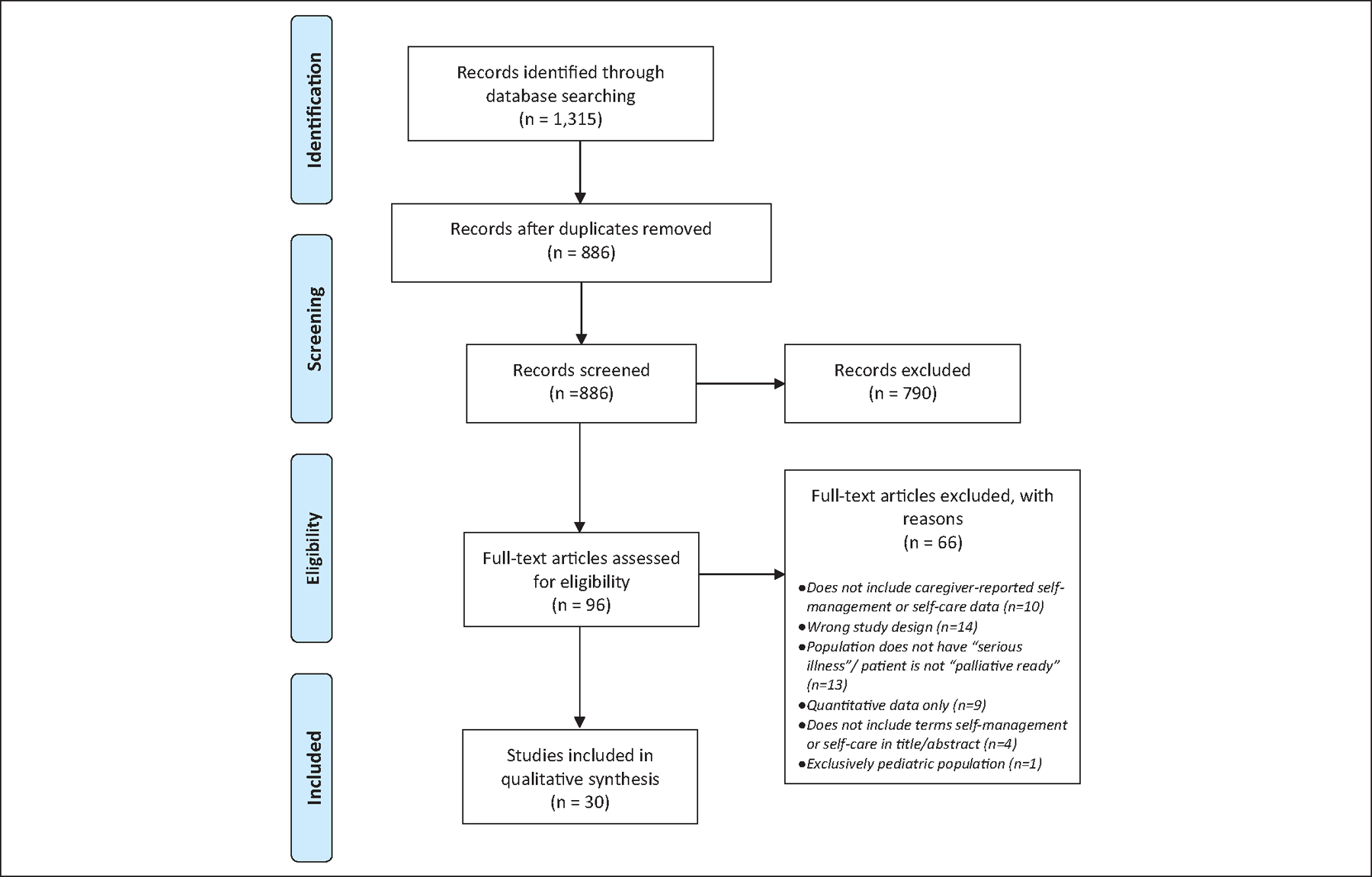

The systematic review process is depicted in the PRISMA diagram (Figure 1). Once the articles meeting inclusion criteria from all databases were identified, we used Covidence systematic review software (Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org) to further screen articles in two phases: (a) title/abstract and (b) full text. Study authors worked in teams of three to review articles: two primary reviewers and one to resolve review discrepancies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Source. Moher et al. (2009).

Note. For more information, visit http://www.prisma-statement.org.

The initial search yielded 1,315 references. After removing duplicates, 886 articles were subject to initial review and uploaded into Covidence. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 96 articles were eligible for full-text screening, of which 66 were excluded. This resulted in a final sample of 30 articles (Table 1). Reasons for exclusion included no caregiver-reported self-management or self-care data (n = 10), study design (e.g., metasyntheses, literature reviews, theory-based works; n =14), study population without a chronic, life-limiting illness/not palliative-ready (n = 13), quantitative data only (n = 9), no “self-management” or “self-care” in the title or abstract (n = 4), or exclusively pediatric population (n = 1).

Table 1.

Metasynthesis of Processes of and Factors Affecting Family Caregivers’ Support of Patient Self-Management: Included Articles (n = 30).

| Article Number | Author | Year | Title | Country | Qualitative approach/method | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Applebaum et al. | 2015 | Meaning-centered psychotherapy for cancer caregivers (MCP-C): Rationale and overview | USA | Case study | To demonstrate the experiences of providing care to patients with cancer and how it varies through case study demonstration and how interventions that specifically target meaning-making among informal cancer caregivers serve as a protective role against poor psychosocial outcomes. |

| 2 | Baer & Hanson | 2000 | Families’ perception of the added value of hospice in the nursing home | USA | Mailed survey with three open-ended questions | To determine if family members perceive that hospice improved the care of dying nursing home residents during the last 3 months of life. |

| 3 | Cameron et al. | 2015 | Carers’ views on patient self-care in chronic heart failure | Australia | Qualitative interview study | To examine carers’ views on chronic heart failure patient self-care to identify factors that facilitated, or hindered, patient engagement in chronic heart failure self-care. |

| 4 | Fex et al. | 2011 | Living with an adult family member using advanced medical technology at home | Sweden | Phenomenology | To gain a deeper understanding of the meaning of living with an adult family member using advanced medical technology at home. |

| 5 | Fujinami et al. | 2012 | Quality of life of caregivers and challenges faced in caring for patients with lung cancer | USA | Case study | To describe the current science regarding quality of life of family caregivers of patients with lung cancer. |

| 6 | Golla et al. | 2015 | Unmet needs of caregivers of severely affected multiple sclerosis patients: A qualitative study | Germany | Focus group/interview study | To gain insight into the subjectively unmet needs of caregivers of severely affected multiple sclerosis patients in Germany. |

| 7 | Gysels & Higginson | 2009 | Caring for a person in advanced illness and suffering from breathlessness at home: Threats and resources | UK | Grounded theory | To investigate the caring experience of carers for patients with an advanced progressive illness who suffer from breathlessness. |

| 8 | Holden et al. | 2015 | The patient work system: An analysis of self-care performance barriers among elderly heart failure patients and their informal caregivers. | USA | Mixed methods | To use a human factors systems model to understand the nature and prevalence of barriers to self-care performance by elderly heart failure patients and their informal caregivers. |

| 9 | Johnston et al. | 2012 | Self-care and end of life care—patients’ and carers’ experience a qualitative study utilising serial triangulated interviews. | UK | Framework analysis | To understand patient and carer experiences of advanced cancer at end of life. |

| 10 | Kanter et al. | 2014 | Together and apart: Providing psychosocial support for patients and families living with brain tumors. | Canada | Mixed analysis approach | To identify characteristics of brain tumor patient and caregiver group participants in relation to attendance frequency, and to compare and contrast themes discussed. |

| 11 | Keesing & Rosenwax | 2011 | Is occupation missing from occupational therapy in palliative care? | Australia | Grounded theory | To explore the daily experiences and occupational needs of people at the end of life and their primary carers. |

| 12 | Kutner et al. | 2009 | Support needs of informal hospice caregivers: A qualitative study | USA | Grounded theory | To understand the needs of informal hospice caregivers to inform the feasibility, structure, and content of a telephone-based counseling intervention. |

| 13 | Lilly et al. | 2011 | Can we move beyond burden and burnout to support the health and wellness of family caregivers to persons with dementia? Evidence from British Columbia, Canada | Canada | Qualitative descriptive | To investigate the health and wellness support needs and resources of family caregivers to persons with dementia and how health policy decisions and practices play out in influencing these needs and resources and to apply these findings to a critical discussion of the current health policy and practice environments to identify strategies for enhancing support for caregivers in ways that move beyond the foci on burden and burnout. |

| 14 | Lo et al. | 2016 | The perspectives of patients on health-care for co-morbid diabetes and chronic kidney disease: A qualitative study | Australia | Qualitative descriptive | To explore the perspectives of patients and their carers on the factors influencing health care of those with comorbid diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD) and to gain a broad range of ideas and perspectives concerning the management of diabetes and CKD by patients and carers and to allow emergence and discussion of key issues and perspectives. |

| 15 | Lockie et al. | 2010 | Experiences of rural family caregivers who assist with commuting for palliative care | Canada | Qualitative descriptive | To examine the experiences of family palliative caregivers who commute from rural and remote locales with a family member receiving advanced cancer care and to broaden knowledge about the demands of family caregiving in that context. |

| 16 | Martinez-Marcos & De la Cuesta-Benjumea | 2014 | Women’s self-management of chronic illnesses in the context of caregiving: A grounded theory study | Spain | Grounded theory | To uncover women caregivers’ management of their chronic illnesses while taking care of a dependent relative. |

| 17 | Mason et al. | 2016 | “My body’s falling apart.” Understanding the experiences of patients with advanced multimorbidity to improve care: Serial interviews with patients and carers. | UK | Qualitative interview study | To understand the experiences and perceptions of people with advanced multimorbidity to inform improvements in palliative and end-of-life care. |

| 18 | Masters et al. | 2013 | Programmes to support chronic disease self-management: Should we be concerned about the impact on spouses? | Australia | Mixed methods | To examine the impact of a chronic disease self-management support intervention on spouses, by investigating the levels of spousal strain for spouses of older adults with multiple chronic conditions. |

| 19 | Morales-Asencio et al. | 2014 | Living with chronicity and complexity: Lessons for redesigning case management from patients’ life stories—A qualitative study | Spain | Qualitative study based on life stories and interviews | To examine patients’ life stories to gain a better understanding of chronic disease experiences, both of patients and of their family caregivers, in relation to health services and the mechanisms developed to cope with the disease, so that new keys to model case management for patients with complex chronic diseases can be identified. |

| 20 | Nguyen et al. | 2017 | Barriers to technology use among older heart failure individuals in managing their symptoms after hospital discharge | Canada | Qualitative descriptive | To describe the experiences of older individuals with heart failure and their informal caregivers in their use of technology for heart failure self-care. |

| 21 | Pappa et al. | 2017 | Self-management program participation and social support in Parkinson’s Disease: Mixed methods evaluation | USA | Qualitative descriptive | To understand if the Stanford Chronic Disease Self-Management Program increases perceived social support for individuals with Parkinson’s disease and their caregivers. |

| 22 | Perzynski et al. | 2017 | Barriers and facilitators to epilepsy self-management for patients with physical and psychological co-morbidity | USA | Qualitative interview study | To identify and explore the range of factors that can impede or promote successful epilepsy self-management, to inform future epilepsy self-management interventions for persons who have epilepsy complicated by comorbid mental health conditions and serious medical events. |

| 23 | Retrum et al. | 2013 | Patient and caregiver congruence: The importance of dyads in heart failure care | USA | Qualitative secondary analysis | To examine for congruence between heart failure patients and their caregivers on the ways in which patient–caregiver dyads talk about how they manage the challenges of living with heart failure. |

| 24 | Rolley et al. | 2011 | The caregiving role following percutaneous coronary intervention | Australia | Focus group study | To describe the experience of caregivers of individuals who have had a percutaneous coronary intervention. |

| 25 | Savage et al. | 2015 | The experiences and needs of family carers of people with diabetes at the end of life | Australia | Qualitative interview study | To collect information from family carers of people with diabetes requiring palliative care about their views and experiences of managing a family member’s diabetes at the end of life. |

| 26 | Sussman et al. | 2016 | Family members’ or friends’ involvement in self-care for patients with depressive symptoms and comorbid chronic conditions | Canada | Qualitative interview study | To describe perceptions of the involvement of family and friends in self-care in patients with depressive symptoms and comorbid chronic conditions. |

| 27 | Wang et al. | 2012 | Patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease feel safe when treated at home: A qualitative study | Norway | Qualitative interview study | To explore chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients’ experiences of an early discharge hospital at home treatment program. |

| 28 | Ward et al. | 2011 | With good intentions: Complexity in unsolicited informal support for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. A qualitative study | Australia | Qualitative interview study informed by thematic analysis | To uncover the ways in which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with chronic illness experience informal unsolicited support from peers and family members. |

| 29 | Williams et al. | 2013 | Hope against hope: Exploring the hopes and challenges of rural female caregivers of persons with advanced cancer | Canada | Narrative analysis of journal entries | To describe the experience of rural female caregivers caring for a family member with advanced cancer, and to describe what fosters their hope. |

| 30 | Wingham et al. | 2015 | Needs of caregivers in heart failure management: A qualitative study | UK | Qualitative study informed by thematic analysis | To identify the needs of caregivers supporting a person with heart failure and to inform the development of a caregiver resource to be used as part of a home-based self-management program. |

Article publication years ranged from 2000 to 2017. Articles (n = 30) represented an international sample of 935 family caregivers from eight countries, including the United States (27%), Australia (23%), Canada (20%), the United Kingdom (13%), Spain (7%), Germany (3%), Norway (3%), and Sweden (3%). The average caregiver sample size was 31; however, two large studies (n = 238; n = 292; Baer & Hanson, 2000; Kanter et al., 2014) skewed these results, which when excluded brought the average sample size to 15.

Family caregivers ranged in age from 18 to 89 years and represented individual family caregivers of patients with advanced cancers (20% including lung, central nervous system, colorectal, breast, hematological, prostate, gynecological, melanoma, and esophageal), heart disease (20%), progressive neurological disease (10% including dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis), diabetes (7%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (3%), and other, chronic, life-limiting conditions (40%).

Quality Appraisal

Review teams evaluated each article for quality using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP; Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2014), bringing quality-related concerns to the team for discussion. Among included articles, most studies were of moderate to good quality (Table 2), with some articles lacking detail on study design or analytic approach.

Table 2.

CASP Quality Appraisal Findings for Metasynthesis (n = 30 Articles).

| CASP criteria | Yes | Cannot tell | No |

|---|---|---|---|

| Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | 29 | 1 | 0 |

| Is the qualitative methodology appropriate? | 26 | 3 | 1 |

| Was the research design appropriate to the aims of the research? | 26 | 2 | 2 |

| Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | 19 | 6 | 5 |

| Were the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | 27 | 2 | 1 |

| Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | 9 | 6 | 15 |

| Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | 24 | 4 | 2 |

| Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | 23 | 3 | 4 |

| Is there a clear statement of findings? | 27 | 2 | 1 |

| Is the research valuable? | 27 | 0 | 3 |

Note. CASP = Critical Appraisal Skills Programme.

Data Abstraction

We created a data extraction form that included study design and sample characteristics, and coding categories on self-management processes, facilitators, and barriers. Following review of all articles in the sample, four coders developed the initial coding scheme (S.L.F., J.N.D.-O., D.S.-G., R.W.) with the categories of Learning Needs, Emotions, Activating Resources, Advocating for the Patient, Performing Health Care Tasks, Facilitators/Barriers, and Other. Team members then independently extracted verbatim all data in each article related to these categories, including reported themes, subthemes, and participant quotes. Any disagreements that could not be resolved in teams were brought to the whole team for discussion. We created a data display matrix to capture all data from all included articles.

Data Synthesis

Coders (S.L.F., J.N.D.-O., D.S.-G., R.W., V.J.E.L., Y.H., A.W., T.W.) independently and then jointly reviewed the extracted data in all categories, adjusting data coded in each category if necessary. Coders then synthesized similar codes into themes. All authors reviewed and discussed coding decisions until reaching consensus on final themes.

The final themes describing family caregivers’ processes to support patient self-management were “Focusing on the Patient’s Illness Needs,” “Activating Resources to Support Oneself as the Family Caregiver,” and “Supporting a Patient Living with a Chronic, Life-Limiting Illness,” which included several subprocesses discussed below. We identified specific tasks (i.e., the essential work to support patient self-management) and skills (i.e., specific, measurable abilities needed to complete tasks) associated with each process (Samson & Siam, 2008). We also created a taxonomy to capture factors that emerged as affecting family caregivers’ processes in support of patient self-management, including Personal Characteristics, Health Status, Resources, Environmental Characteristics, and Health Care System.

Results

Family Caregivers’ Processes to Support Patient Self-Management

We report family caregivers’ processes to support patient self-management in Table 3. These include Focusing on the Patient’s Illness Needs, Activating Resources to Support Oneself as the Family Caregiver, and Supporting a Patient Living with a Chronic, Life-Limiting Illness.

Table 3.

Family Caregivers’ Processes to Support Patient Self-Management.

Focusing on the Patient’s Illness Needs.

The process of “Focusing on the Patient’s Illness Needs” encompasses the tasks and skills that enabled family caregivers to learn about and support patients’ self-management of their illness. As part of this process, family caregivers learned about the patient’s health condition and associated caregiving tasks and skills, activated health care resources for the patient, and provided support to the patient in various ways. More specifically, learning about the health condition included acquiring information (Fujinami et al., 2012; Pappa et al., 2017; Retrum et al., 2013; Savage et al., 2015) and learning the caregiving skills that caregivers could be called upon to perform, such as managing medications (Cameron et al., 2015; Gysels & Higginson, 2009; Holden et al., 2015; Kanter et al., 2014; Mason et al., 2016; Wingham et al., 2015) and supporting activities of daily living (Cameron et al., 2015; Johnston et al., 2012; Keesing & Rosenwax, 2011; Kutner et al., 2009; Masters et al., 2013; Morales-Asencio et al., 2014; Ward et al., 2011; Wingham et al., 2015). Performing health care tasks safely, skillfully, and confidently was a widely reported skill (Fex et al., 2011; Fujinami et al., 2012; Golla et al., 2015; Nguyen et al., 2017; Savage et al., 2015; Ward et al., 2011; Wingham et al., 2015).

In several articles, the task of learning to manage fluctuations in the patient’s illness was specified, with the related skills of managing symptoms (Golla et al., 2015; Gysels & Higginson, 2009; Holden et al., 2015; Kanter et al., 2014; Lo et al., 2016; Lockie et al., 2010; Mason et al., 2016) and acute exacerbations (Fex et al., 2011; Gysels & Higginson, 2009; Johnston et al., 2012; Masters et al., 2013; Wingham et al., 2015), and planning in the presence of uncertainty (Fex et al., 2011; Golla et al., 2015; Gysels & Higginson, 2009; Johnston et al., 2012; Mason et al., 2016). The uncertain timing and nature of acute exacerbations were reported to be disconcerting for family caregivers. A family caregiver of a patient with heart failure shared her feelings about the unpredictability of the patient experiencing breathlessness: “I’d like somebody to tell me when it’s gonna happen. It’s like living with a pressure cooker or a time bomb.” (Gysels & Higginson, 2009, p. 155). The process of family caregivers’ skill development in managing acute exacerbations was also reported in another study: “Carers described care in cases of acute exacerbations as a learning process. After the first incidents, they knew better what to expect and what was appropriate from the advice they had received from professionals” (Gysels & Higginson, 2009, p. 159).

The process of activating health care resources for the patient included identifying health care resources that supported patient care, such as obtaining information and support from health care professionals (Fex et al., 2011; Fujinami et al., 2012; Kutner et al., 2009; Lilly et al., 2011; Lo et al., 2016; Lockie et al., 2010; Morales-Asencio et al., 2014; Nguyen et al., 2017; Rolley et al., 2011; Wingham et al., 2015) with clear communication (Lockie et al., 2010), adapting the home environment, including acquiring assistive devices (Fex et al., 2011; Fujinami et al., 2012; Golla et al., 2015; Gysels & Higginson, 2009; Masters et al., 2013), using a home health aide or sitter (Holden et al., 2015; Keesing & Rosenwax, 2011; Lo et al., 2016; Mason et al., 2016; Wingham et al., 2015), and accessing transportation services (Fujinami et al., 2012; Golla et al., 2015; Lo et al., 2016).

Article authors reported various dimensions of the process of how caregivers supported patients. These included supporting the patient’s physical and emotional health (e.g., encouraging physical activity, being optimistic), being an advocate for the patient (e.g., serving as a patient proxy), and providing practical support in the form of everyday tasks (e.g., maintaining the household). Keesing and Rosenwax (2011) summarized the range of support:

Most carers were thrust into the caring role with little preparation and were required to carry out a variety of tasks for the person they cared for, including physical assistance for self-care, transport, care of the home, medication management, financial and emotional support. (p. 333)

Family caregivers’ engagement in the process of “Focusing on the Patient’s Illness Needs” varied depending on the patient’s willingness and ability to engage in self-management. Likewise, the family caregiver–patient self-management partnership varied according to the patient’s health condition, symptom burden, the type of care patients were receiving (e.g., curative, end-of-life), their associated needs, family values and resources, and family caregiver’s health and ability to support patient self-management. Thus, “Focusing on the Patient’s Illness Needs” reflects many types of self-management partnerships wherein the family caregiver performed a function for or on behalf of the patient (e.g., making an appointment) or with the patient in varying degrees ranging from equally shared responsibility (e.g., split household responsibilities) to the family caregiver providing only minimal support (e.g., providing a reminder to check blood sugar).

Activating Resources to Support Oneself as the Family Caregiver.

The process of “Activating Resources to Support Oneself as the Family Caregiver” refers to the activation of a range of resources that assist the family caregiver in sustaining and optimizing their role in supporting patient self-management. Resources reflected psychosocial (Applebaum et al., 2015; Fex et al., 2011; Gysels & Higginson, 2009; Holden et al., 2015; Keesing & Rosenwax, 2011; Lilly et al., 2011; Lo et al., 2016; Lockie et al., 2010; Martinez-Marcos & De la Cuesta-Benjumea, 2014; Masters et al., 2013; Morales-Asencio et al., 2014; Pappa et al., 2017; Perzynski et al., 2017; Rolley et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2013; Wingham et al., 2015) and spiritual (Williams et al., 2013; Wingham et al., 2015) domains. Examples of tasks and skills related to activating resources include seeking emotional support from other family caregivers, praying, and using respite care. Family caregivers varied in the nature and extent to which they activated resources depending on their and the patient’s fluctuating needs over time. Activation of resources was described as critical to enable family caregivers to sustain themselves in the caregiving role, and multiple modes were often used. As exemplified by Williams and colleagues (2013),

Participants employed multiple self-care strategies to cope through some of the challenges and emotions of the caregiving experience. These included physical outlets, such as eating well, doing yoga, and running. Many participants kept busy in order to cope, and socialized with friends and family, such as going to dinner or for coffee. Some sought professional support such as counseling and set goals for themselves. (p. 6)

Supporting a Patient Living with a Chronic, Life-Limiting Illness.

The process of “Supporting a Patient Living with a Chronic, Life-Limiting Illness” comprised tasks and skills in the areas of managing one’s own emotions, managing one’s own physical health, adjusting to being a family caregiver, and making meaning of being a family caregiver. Managing one’s own emotions required that family caregivers address a wide range of feelings that included anxiety, burn out, and uncertainty among nearly 40 distinct negative emotions reported, reflecting high emotional burden. Applebaum and colleagues (2015) reported an example of the interaction of emotional and physical issues for family caregivers, illustrating the overlap of the tasks of managing one’s own emotions and one’s own physical health:

[the family caregiver] was experiencing chronic worry about her husband and her future. This worry interfered with her sleep and ability to concentrate, and was associated with somatic symptoms, such as nausea and muscle tension. She also reported at times feeling hopeless about the future and fearful of living life without her husband, and abandoned by her daughters for not being present and helping to care for him. (p. 7)

Family caregivers also reported positive emotions associated with the family caregiver role, though with less frequency. Positive emotions included feeling privileged, devotion, love, gratitude (Kutner et al., 2009; Perzynski et al., 2017; Sussman et al., 2016; Williams et al., 2013), as well as acceptance and making the best of the situation (Gysels & Higginson, 2009; Lockie et al., 2010; Morales-Asencio et al., 2014; Sussman et al., 2016; Williams et al., 2013).

Adjusting to being a family caregiver required getting used to a new role or adjusting to being a family caregiver in a way that was different from previous caregiving experience (i.e., different patient, different health care condition, different tasks/skills). Adjustment required setting expectations appropriately and planning and managing one’s time to be a family caregiver. Acknowledging the patient’s prognosis was described as a challenging task of living with a patient with a, chronic, life-limiting illness due to its implications for the patient and for the nature, length, and burden of caregiving.

For meaning-making, family caregivers reflected on what caregiving meant to them personally, the challenges, the benefits, and the opportunities for growth. The tasks of meaning-making identified by family caregivers included identifying positive aspects of caregiving (e.g., exploring and expressing emotions such as love and gratitude) and personal growth (e.g., developing confidence).

Factors Affecting Family Caregivers’ Support of Patient Self-Management

We present the taxonomy of factors affecting family caregivers’ support of patient self-management in Table 4. Categories include Personal Characteristics, Health Status, Resources, Environmental Characteristics, and the Health Care System. We conceptualized factors as potential facilitators or barriers to family caregivers’ support of patient self-management.

Table 4.

Factors Affecting Family Caregivers’ Support of Patient Self-Management.

| Category | Subcategory | Codes |

|---|---|---|

| Personal Characteristics | Caregiver | • Knowledge of treatment options (Wingham et al., 2015) |

| Patient | • Patient empowerment and engagement in self-management (Lo et al., 2016) | |

| Health Status | Caregiver | • Caregiver health and coping (Gysels & Higginson, 2009; Martinez-Marcos & De la Cuesta-Benjumea, 2014; Mason et al., 2016) |

| Patient | • Patient health and coping (Cameron et al., 2015; Lo et al., 2016; Rolley et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2013) | |

| Resources | Financial | • Socioeconomic status (Lockie et al., 2010; Morales-Asencio et al., 2014) |

| • Access to assistive devices (Gysels & Higginson, 2009) | ||

| Environmental Characteristics | Home Community | • Quality of family relationships (Cameron et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2013) |

| • Public awareness of health condition (Lo et al., 2016; Perzynski et al., 2017) | ||

| • Stigma (Gysels & Higginson, 2009; Pappa et al., 2017; Perzynski et al., 2017) | ||

| • Community characteristics and support (Pappa et al., 2017; Perzynski et al., 2017; Retrum et al., 2013; Williams et al., 2013) | ||

| Health Care System | Access | • Access to care (Cameron et al., 2015; Lo et al., 2016; Mason et al., 2016; Morales-Asencio et al., 2014; Perzynski et al., 2017) |

| Navigating system/Continuity of care | • Coordination/consistency of health care professionals (Lilly et al., 2011; Lo et al., 2016; Mason et al., 2016; Morales-Asencio et al., 2014; Wingham et al., 2015) | |

| Relationship with provider | • Quality of communication with health care professionals (Lo et al., 2016; Keesing & Rosenwax, 2011; Wingham et al., 2015) |

Personal Characteristics.

Personal characteristics that affected family caregivers’ ability to support patient self-management related to both family caregiver and patient characteristics. Knowledge of treatment options enabled family caregivers to contribute to decision-making (Wingham et al., 2015). Patient characteristics of empowerment and engagement in self-management were reported as important, affecting family caregivers’ support of patients (Lo et al., 2016).

Health Status.

Health status factors that affected family cargivers included both their own and the patient’s health. Family caregivers’ physical health frequently affected their ability to perform the role (Gysels & Higginson, 2009; Mason et al., 2016). A family caregiver of a patient with COPD was told regarding managing her husband’s oxygen: “‘[You] can’t be running around … because you’re not a young woman yourself’, which I’m not.” (Gysels & Higginson, 2009, pp. 155–6). Family caregiver emotions, such as feeling disheartened or discouraged, could lessen illness management (Martinez-Marcos & De la Cuesta-Benjumea, 2014).

The patient’s physical and emotional health also affected family caregivers’ ability to sustain the caregiver role (Cameron et al., 2015; Lo et al., 2016; Williams et al., 2013). A cancer family caregiver said, “I am having more difficulty now than I have had over the past few months. My mood depends on how my partner is doing. I am tired. I need a break.” (Williams et al., 2013, p. 7). Patients’ recovery time affected family caregivers where a prolonged recovery time adversely affected mood and negatively affected the family caregiver–patient relationship (Rolley et al., 2011)

Financial Resources.

Financial resources affected family caregivers’ support of patient self-management (Gysels & Higginson, 2009; Lockie et al., 2010; Morales-Asencio et al., 2014). Low socioeconomic status contributed to family caregiver stress: “It’s a lot more stress, you know, because … I’m on unemployment leave, so my income isn’t high, and when you’re paying sixty bucks in gas to go out, it gets pricey” (Lockie et al., 2010, p. 80). Socioeconomic determinants also placed individuals in “an unfavorable position to apply material, cognitive, and support resources to cope with the disease” (Morales-Asencio et al., 2014, p. 124). Access to oxygen or assistive devices like a wheelchair affected family caregivers’ ability to take patients out of the home (Gysels & Higginson, 2009).

Environmental Characteristics.

Environmental characteristics that affected family caregivers were related to the home and the community. At home, family relationships affected family caregiver support of patient self-management. Specifically, family caregivers felt their relationship with the patient affected the patient’s uptake of self-care (Cameron et al., 2015) and their own hope (Williams et al., 2013).

In the community, public awareness of a health condition affected family caregivers’ ability to support patient self-management due to associated levels of stigma, social support, and resources (Lo et al., 2016; Perzynski et al., 2017). Stigma related to the patient’s appearance or diagnosis was cited as affecting family caregivers’ ability to venture from home (Gysels & Higginson, 2009), to deal with social issues related to the health condition (Pappa et al., 2017), and also affected the availability of social support (Perzynski et al., 2017).

Social support could facilitate family caregivers’ support of patient self-management through peer learning experiences and a feeling of belonging (Pappa et al., 2017). A Parkinson’s disease family caregiver remarked, “You get with these people and you sit down and everyone is frank … they tell you what the problems are and how they’ve dealt with them, or in some cases, how they haven’t dealt with them” (Pappa et al., 2017, p. 91). Lack of social support was reported as a barrier that could lead to social isolation (Perzynski et al., 2017).

Health Care system.

Factors related to the health care system included access to care, navigating the health care system and continuity of care, and relationships with providers. Access to care was reported in the form of waiting room times and free parking (Lo et al., 2016), availability of public transportation (Perzynski et al., 2017), the level of physical demands required to attend clinics (Mason et al., 2016), and availability of clinical support (Wang et al., 2012), particularly telephone advisory services (Cameron et al., 2015; Morales-Asencio et al., 2014).

Continuity of care was described in terms of both consistency of health care professionals (Mason et al., 2016; Morales-Asencio et al., 2014) and coordination of care (Lo et al., 2016). A diabetes/chronic kidney disease family caregiver said the following:

There is no consistency in terms of seeing the same doctor all the time. So many changes, so many different doctors … each of them is very considerate but clearly clueless about the uniqueness of the patients. (Mason et al., 2016, p. 61)

A shared medical record was reported as a means of improving communication and coordination of care, especially between primary and tertiary health care professionals (Lo et al., 2016). Decreasing the need for multiple appointments and the potential of conflicting appointment times was also cited as helpful to family caregivers (Lo et al., 2016).

Family caregivers’ relationship with providers was reported in terms of the inclusion and quality of family caregiver–provider communication. Some family caregivers described poor communication as “disempowering” and frustrating (Keesing & Rosenwax, 2011). A family caregiver reported, “Well, I just think it’s a disgrace to the system because they didn’t listen or talk to me properly, they didn’t respect Jane’s wishes properly” (p. 333). Inclusion of family caregivers in health care communication facilitated their support of patient self-management by ensuring that family caregivers can both provide and receive important information about the patient. Decentralizing services to community clinics was reported as helpful by improving access to care through decreased travel time, improved parking, greater use of home visits and transportation services, reducing waiting times, and greater choice of appointment times (Lo et al., 2016).

Discussion

For this metasynthesis, our aim was to synthesize the data on family caregivers’ processes to support patient self-management during chronic, life-limiting illness and factors affecting their support. Findings indicate that the family caregiver role is multidimensional, with numerous tasks and skills required to support patient self-management as well as the health of the family caregiver. These findings are consistent with population-based reports that detail the various activities and tasks performed by family caregivers (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2017; National Alliance for Caregiving, 2015). In a 2015 U.S. survey of 1,248 family caregivers, an estimated 43.5 million adult caregivers provided an average of 24 hours of weekly assistance with activities of daily living, monitoring patient health conditions to adjust care, and advocating and communicating with health professionals and services on behalf of patients (National Alliance for Caregiving, 2015).

Across studies, family caregivers’ reports suggest an overlap or tension between supporting patients’ self-management and managing on the patients’ behalf. Family caregivers reported needing to manage for the patient rather than with them if the patient was unwilling or unable to perform health care tasks themselves. For example, managing medications was an often-reported skill; however, a family caregiver filling the patient’s pill box versus handing the pill to the patient with a glass of water delineates supporting patient self-management from patient self-management.

Although patients are the central actors in self-management with family caregivers in a supportive role, the degree or nature of support the family caregiver is called upon to provide may be affected by changes in the patient’s health, positive or negative, as well as the nature of the patient–family caregiver relationship (harmony, distance, etc.). It is reasonable to expect that a family caregiver would increasingly act on the patients’ behalf in the presence of progressive disease. While perhaps not a goal for all dyads, achieving and sustaining a balanced, collaborative patient–family caregiver relationship in managing chronic, life-limiting illness may be challenging, given ever-changing dynamics.

A second cross-cutting finding was the tension between family caregivers’ support of the patient and the need to manage their own health condition(s). This tension is revealed in the identification of processes wherein family caregivers support patients (Focusing on the Patients’ Illness Needs) and support themselves in the family caregiver role (Activating Resources to Support Oneself as the Family Caregiver, Supporting a Patient Living with a Chronic, Life-Limiting Illness). Family caregivers reported difficulty in managing these processes concurrently and described a high emotional burden as a result.

Family caregivers must take care of themselves to be able to take care of patients; however, family caregivers’ health may likewise be poor, to the extent that in one clinician’s office they may be the family caregiver, but in another they may be the patient, and the patient and family caregiver roles are reversed. These tensions illustrate the complexity of the patient–family caregiver dyad relationship and reveal what is essentially three intertwined components: patient self-management, caregiver self-management, and patient-family management.

Family members expressed considerable emotional distress due to the caregiving role, including depression, burnout, emotional exhaustion, and resentment. Greater attention to the assessment and health care of family caregivers’ emotional status is critical to improving health outcomes for family caregivers and patients. A novel aspect of the study’s findings is the potential impact of family caregivers’ ability to manage their own emotions on patients’ self-management practices. Study findings suggest that negative family caregiver emotions, such as feeling disheartened or discouraged, could lessen illness management (Martinez-Marcos & De la Cuesta-Benjumea, 2014), whereas positive emotions such as acceptance and making the best of the situation (Gysels & Higginson, 2009; Lockie et al., 2010; Morales-Asencio et al., 2014; Sussman et al., 2016; Williams et al., 2013) were sustaining. Patients’ perception of the emotional burden they place on their family members has been shown to correlate with their own mood and preferences for care (Etkind et al., 2018). Thus, due to the symbiotic nature of the patient–family caregiver relationship, more positive emotions and better management of negative emotions among family caregivers can support patient self-management. Research is needed to further understand the relationship between the emotional regulation of family caregivers, patients’ self-management practices, behaviors, and preferences, and family caregivers’ health.

State of the Qualitative Literature on Family Caregiver Support of Patient Self-Management

While it is possible that we did not capture all relevant articles for this metasynthesis, we can make some observations about the state of the literature on family caregiver support of patient self-management. This literature is emerging, as evidenced by our not achieving “saturation” for all processes and factors. Several factors were identified in only a few of the included articles, which we believe reflects the state of the literature rather than that these factors are unimportant. In addition, across studies, it was not feasible to examine the influence of care setting, country, or type of illness on family caregivers’ support of patients’ self-management due to the relatively small sample size. Continued qualitative research and a review of the quantitative literature would be useful to more fully describe family caregiver processes, facilitators, and barriers to self-management.

We noted significant gaps in the reporting of family caregiver samples. A main shortcoming of several studies was providing incomplete or no description of family caregiver samples. Data were often missing on key participant characteristics, including the relationship of family caregivers to patients (e.g., spouse, child) and other demographic information, such as race and ethnicity. When family caregiver data were provided, it was often presented in a way that limited comparisons for review purposes (e.g., no means and ranges). More complete sample descriptions would help to elucidate and indicate applicability of findings to other caregiver populations. In addition, although family caregiver data were often missing or sparse, authors consistently reported patient demographics, whether to describe patients for whom family caregivers were providing care or to describe a patient sample included in the same study. This discrepancy in sample description makes family caregivers seem ancillary or secondary, despite being the focus of the study. This finding reflects dynamics in the clinical setting where the patient is usually, and appropriately, the focus of care; however, while family caregivers usually function in a supportive role, we believe they warrant independent consideration rather than solely through the lens of the patient.

Authors of the articles included in this metasynthesis themselves reported some limitations to their work (see CASP criteria, Table 2). One was difficulty accessing family caregivers, which resulted in complex recruitment protocols as well as a lack of participant diversity, particularly in sex, age, demographic region (mostly urban), ethnicity, and relationship to the patient (mostly spouses). Recall bias and bias due to the patient’s presence during the interview were also reported. We highlight these limitations as opportunities to enhance the methodological rigor of caregiver studies in the future.

Contribution and Recommendations for Future Directions

This metasynthesis enhances our understanding of how family caregivers support patient self-management in several ways. First, findings detail processes in which family caregivers engage to support patient self-management, as well as factors affecting support. Both processes and factors have previously been described from the patient perspective only (Schulman-Green et al., 2012, 2016). While this area of inquiry is emerging, this metasynthesis yielded an initial taxonomy of factors affecting family caregivers’ support of patient self-management. Future research in this area will enable continued elaboration of processes and factors related to family caregivers’ support of patient self-management. Second, our findings reveal two key tensions experienced by family caregivers: balancing a patient’s needs with their own health needs, and supporting patient self-management versus managing on the patient’s behalf. Negotiating these tensions should be prioritized as part of support for family caregivers. Third, although it has been recognized that family caregivers experience emotional distress (Feast et al., 2016; Ochoa et al., 2019), our findings reveal the very wide range of emotions experienced by family caregivers and the impact of emotions on self-management support.

While we have elucidated processes and factors related to family caregiver support of patient self-management, there remain many pertinent understudied areas. For example, future research might include the experience of supporting patient self-management by one versus multiple family caregivers, racial and ethnic differences in family caregiver support of patient self-management, the relationship between family self-management support and spirituality/faith, and the use of digital health and health tracking in family caregiver support of patient self-management. Work and financial strain (i.e., financial toxicity) consequent to serious illness has gained attention ( Garland et al., 2019) and should likewise be explored in relation to family support of self-management.

Implications for Practice

Clinicians have an integral role in assisting family caregivers to support patient self-management. Clinicians should assess the needs of family caregivers regarding their responsibilities and roles in decision-making, their caregiving preferences, their mental health and occupational needs, as well as the impact of caregiving on their quality of life (International Family Nursing Association, 2015, 2017). Referral to mental health professionals may be necessary to improve stress, coping, and caregiving capacity. Case management, holistic management by health professionals and specialists, and government involvement in support of caregiving may enable family caregivers to mentally and emotionally self-regulate and to cope with the patient’s illness in service of helping the patient to self-manage.

Implications for Family Caregiver Interventions

Study findings support three guiding principles for family caregiver intervention development. Most central is the necessity of including family caregiver–specific elements in multicomponent interventions aimed at optimizing patient self-management. Second, given the varying needs and circumstances of individual family caregivers over time (Schulz et al., 2017), a family caregiver intervention will likely need an initial comprehensive assessment with one to three skills selected for targeted enhancement. Such an approach was recently recommended in a National Academy of Medicine (formerly Institute of Medicine) report on U.S. family caregiving (Institute of Medicine, 2015) and has been described in the family caregiver intervention development literature (Dionne-Odom et al., 2018). Third, as shown in Table 4, family caregiver elements might be characterized as social-, system-, and environmental-level factors, suggesting that interventions targeting individual- and/or dyad-level behaviors and practices may not be sufficient by themselves to improve self-management of patients with chronic, life-limiting illness. Interventions may need to include not only multicomponent interventions but also multilevel interventions that target patient and family caregiver factors at the individual, dyad, and system levels (Paskett et al., 2016).

Implications for Self- and Family Management Theory

Findings of this metasynthesis will advance the Self- and Family Management Framework (Grey et al., 2015) by more fully describing the multitude of tasks and skills required of family caregivers in supporting patient self-management. These findings, when compared with the findings of the patient metasyntheses (Schulman-Green et al., 2012, 2016), are complementary and reflective of key self-management processes and factors affecting self-management from two different perspectives. Specification of tasks and skills for both patients and family caregivers assists in identification of targets for assessment and intervention development to enhance patients’ and family caregivers’ self-management, health, and quality of life.

Conclusion

Through this qualitative metasynthesis, we identified three themes characterizing family caregivers’ processes to support patient self-management, including “Focusing on the Patient’s Illness Needs,” “Activating Resources to Support Oneself as the Family Caregiver,” and “Supporting a Patient Living with a Chronic, Life-Limiting Illness.” A taxonomy describing factors affecting family caregivers’ support also emerged and included the areas of Personal Characteristics, Health Status, Resources, Environmental Characteristics, and the Health Care System. Across chronic, life-limiting illnesses, family caregivers’ support of patient self-management is complex, encompassing numerous tasks and skills for each process of care and influenced by multiple factors and dynamics. While additional research is necessary to specify findings, our synthesis contributes to the understanding of what family caregivers do to support patient self-management during life-limiting illnesses requiring long-term management, as well as what can help or hinder their activities in this demanding role. Assessment and interventions to support and sustain family caregivers as they assist with patient self-management during chronic, life-limiting illness are needed.

Supplementary Material

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was supported by the Palliative Care Research Cooperative Group funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research, U24NR014637. Dr. Dionne-Odom receives support from the National Institute of Nursing Research (R00NR015903) and the National Cancer Institute (R01CA229197). This publication was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations through the National Clinician Scholars Program. This publication was made possible by CTSA Grant Number TL1 TR001864 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH.

Biographies

Author Biographies

Dena Schulman-Green, PhD, is an associate professor at the New York University Rory Meyers College of Nursing in New York, NY, USA. Her program of research focuses on the timely integration of palliative care into self- and family management of cancer and other serious, chronic illnesses, with the ultimate goal of increasing understanding and use of palliative care as a catalyst to productive self- and family management. She develops and tests interventions in partnership with patients, family caregivers, and health care providers that are designed to enable effective, collaborative, and culturally relevant self- and family management. Recent publications include “Integrating Cancer Family Caregivers Into Palliative Oncology Care Using the Self- and Family Management Framework” in Seminars in Oncology Nursing (2018, with D. Schulman-Green & S. L. Feder), “Supporting Self-Management in Palliative Care Throughout the Cancer Care Trajectory” in Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care (2018, with D. Schulman-Green, A. Brody, S. Gilbertson-White, R. Whittemore & R. McCorkle), and “A Revised Self- and Family Management Framework” in Nursing Outlook (2015, with M. Grey, D. Schulman-Green, K. Knafl, & N. Reynolds).

Shelli L. Feder, PhD, APRN, ACHPN, is an assistant professor at the Yale School of Nursing in West Haven, CT, USA, and an applied, organizational, health services researcher. Her program of research focuses on examining and implementing models of palliative care delivery within large and complex health care systems with a focus on Vterans and patients with cardiopulmonary conditions. Recent publications include “Perspective of Patients in Identifying Their Values-Based Priorities” in Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (2019, with S. Feder et al.), “Validation of the ICD-9 Diagnostic Code for Palliative Care in Patients Hospitalized With Heart Failure Within the Veterans Health Administration” in American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care (2018, with S. L. Feder et al.), and “‘They Need to Have an Understanding of Why They’re Coming Here and What the Outcomes Might Be’. Clinician Perspectives on Goals of Care for Patients Discharged From Hospitals to Skilled Nursing Facilities” in Journal of Pain and Symptom Management (2017, with S. L. Feder, M. Campbell Britton, & S. I. Chaudhry)

J. Nicholas Dionne-Odom, PhD, APRN, ACHPN, is an assistant professor in the School of Nursing at the University of Alabama at Birmingham in Birmingham, AL, USA. His program of research focuses on the development, testing, and implementation of early palliative care coaching interventions to support family caregivers of persons with newly diagnosed serious illnesses, particularly advanced cancer and heart failure. He is also interested in optimizing the role families play in supporting patient decision-making during serious illness and at end of life. Recent publications include “Effects of a Telehealth Early Palliative Care Intervention for Family Caregivers of Persons With Advanced Heart Failure: The ENABLE CHF-PC Randomized Clinical Trial” in JAMA Network Open (2020, with J. N. Dionne-Odom et al.), and “Benefits of Early Versus Later Palliative Care to Informal Family Caregivers of Persons With Advanced Cancer: Outcomes From the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial” in Journal of Clinical Oncology (2015, with J. Dionne-Odom et al.).

Janene Batten, MLS, is the nursing librarian at the Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library, Yale University. As the librarian for the Yale School of Nursing, and liaison to the Yale New Haven Hospital nurses, she has extensive experience teaching evidence-based research principles. She also works with nursing faculty, graduate and doctoral students, assisting them with all aspects of their research. She has authored publications that promote the inclusion of librarians as partners in clinical practice and developing research, and, as an expert searcher, is a coauthor on a number of systematic reviews. She is faculty in the annual 3-day Institute Supporting Clinical Care: An Institute in Evidence-based Practice for Medical Librarians, held in both Denver, CO, and in Australia. Recent publications include “Librarians as Methodological Peer Reviewers for Systematic Reviews: Results of a Survey” in Research Integrity and Peer Review (2019, H. K. Grossetta Nardini et al.), “Agreement Between Actigraphic and Polysomnographic Measures of Sleep in Adults With and Without Chronic Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis” in Sleep Medicine Reviews (2019, with S. Conley et al.), and “Sexual Minority Men and the Experience of Undergoing Treatment for Prostate Cancer: An Integrative Review” in European Journal of Cancer Care (2019, with M. Moore, J. Batten, & M. Lazenby)

Victoria Jane En Long, MPH, is a second-year medical student at Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore. She completed her MPH in social and behavioral science at Yale School of Public Health, focusing on caregiving and palliative care in the global health setting. As a medical student, she continues to be engaged in palliative care research in the hospital setting, alongside receiving her clinical education.

Yolanda Harris, PhD, PNP, CRNP-AC, MSCN is an assistant professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, School of Nursing in Birmingham, AL, USA. She has been involved in several multi-site research studies focusing on the care of children living with pediatric onset multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating disorders of the central nervous system. Her current research is investigating the cognitive effects of MS on children in comparison to adults with MS and healthy controls. Her current research interests include quality of life and health disparities that affect families of individuals with multiple sclerosis and disease. Her recent researches are published in Multiple Sclerosis Journal, Journal of Child Neurology, Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, and Annuals of Clinical and Translatioal Neurology.

Abigail Wilpers, PhD, WHNP-BC, is a postdoctoral research associate at the Yale School of Medicine, and a Fetal Therapy Nurse at the Fetal Care Center of Yale New Haven Hospital. As a clinician and researcher, Dr. Wilpers strives to provide and improve person & family-centered care for women and families following fetal diagnosis during pregnancy. She is particularly focused intrauterine surgery to treat fetal anomalies, and perinatal palliative care. Her recent reseraches are published in Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, and Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing.

Tiffany Wong, RN, MS, is an instructor in the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College, NH, USA. She has a broad research training and experience, ranging from epidemiology to neuroimaging in the study of human brain function in different pathological conditions. Her clinical work is in the management of acute cerebrovascular accidents and recovery from secondary neurologic dysfunction. It is her firm belief that improving function and comfort is the foundation of patient care. Her diverse research interest has lately expanded to include in learning about approaches to palliative care intervention in chronic illness. Recent publications include “Impaired Social Processing in Autism and Its Reflections in Memory: A Deeper View of Encoding and Retrieval Processes” in Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2014, with R. S. Brezis, T. Galili, T. Wong, & J. I. Piggot), and “Brain Dysfunction During Facial Discrimination in Schizophrenia: Selective Association to Affect Decoding” in Psychiatry Research (2011, with J. Quintana et al.)

Robin Whittemore, PhD, APRN, FAAN, is a professor, at Yale School of Nursing in West Haven, CT, USA. Her research has focused on the development and evaluation of interventions to promote self-management and psychosocial adjustment in Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes. Her work has also focused on reducing health disparities in Type 2 diabetes and the use of technology to support diabetes self-management. Recent publications include “An eHealth Program for Parents of Adolescents With T1DM Improves Parenting Stress: A Randomized Control Trial” in Diabetes Educator (2020, with R. Whittemore et al.), “Challenges to Diabetes Self-Management for Adults With Type 2 Diabetes in Low-Resource Settings in Mexico City: A Qualitative Descriptive Study” in International Journal for Equity in Health (2019, with R. Whittemore et al.), and “The Experience of Partners of Adults With Type 1 Diabetes: An Integrative Review” in Current Diabetes Reports (2018, with R. Whittemore, R. Delvy, & M. M. McCarthy).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Applebaum AJ, Kulikowski JR, & Breitbart W (2015). Meaning-centered psychotherapy for cancer caregivers (MCP-C): Rationale and overview. Palliative and Supportive Care, 13(6), 1631–1641. 10.1007/978-3-319-41397-6_12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer WM, & Hanson LC (2000). Families’ perception of the added value of hospice in the nursing home. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48(8), 879–882. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb06883.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, Turner A, & Hainsworth J (2002). Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: A review. Patient Education and Counseling, 48(2), 177–187. 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00032-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron J, Rhodes KL, Ski CF, & Thompson DR (2015). Carers’ views on patient self-care in chronic heart failure. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(1–2), 144–152. 10.1111/jocn.13124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coalition to Transform Advanced Care. (2015). Advanced care project report. https://www.thectac.org/key-initiatives/advanced-care-project/

- Corry M, While A, Neenan K, & Smith V (2015). A systematic review of systematic reviews on interventions for caregivers of people with chronic conditions. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(4), 718–734. 10.1111/jan.12523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2014). CASP checklists. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- Dionne-Odom JN, Taylor R, Rocque G, Chambless C, Ramsey T, Azuero A, Ikankova N, Martin MY, & Bakitas MA (2018). Adapting an early palliative care intervention to family caregivers of persons with advanced cancer in the rural deep south: A qualitative formative evaluation. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 55(6), 1519–1530. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkind SN, Bone AE, Lovell N, Higginson IJ, & Murtagh FEM (2018). Influences on care preferences of older people with advanced illness: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66(5), 1031–1039. 10.1111/jgs [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feast A, Moniz-Cook E, Stoner C, Charlesworth G, & Orrell M (2016). A systematic review of the relationship between behavioral and psychological symptoms (BPSD) and caregiver well-being. International Psychogeriatrics, 28(11), 1761–1774. 10.1017/S1041610216000922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fex A, Flensner G, Ek A-C, & Söderhamn O (2011). Living with an adult family member using advanced medical technology at home. Nursing Inquiry, 18(4), 336–347. 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2011.00535.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujinami R, Otis-green S, Klein L, Sidhu R, & Ferrell B (2012). Quality of life of family caregivers and challenges faced in caring for patients with lung cancer. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 16(6), E210–E220. 10.1188/12.CJON.E210-E220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland A, Jeon S-H, Stepner M, Rotermann M, Fransoo R, Wunsch H, Scales DC, Iwashyna TJ, & Sanmartin C (2019). Effects of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular health events on work and earnings: A population-based retrospective cohort study. CMAJ, 191(1), E3–E10. 10.1503/cmaj.181238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golla H, Mammeas S, Galushko M, Pfaff H, & Voltz R (2015). Unmet needs of caregivers of severely affected multiple sclerosis patients: A qualitative study. Palliative and Supportive Care, 13(6), 1685–1693. 10.1017/S1478951515000607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grey M, Knafl K, & McCorkle R (2006). A framework for the study of self- and family management of chronic conditions. Nursing Outlook, 54(5), 278–286. 10.1016/j.outlook.2006.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grey M, Schulman-Green D, Knafl K, & Reynolds NR (2015). A revised self- and family management framework. Nursing Outlook, 63(2), 162–170. 10.1016/j.outlook.2014.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gysels MH, & Higginson IJ (2009). Caring for a person in advanced illness and suffering from breathlessness at home: Threats and resources. Palliative and Supportive Care, 7(2), 153–162. 10.1017/S1478951509000200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden RJ, Schubert CC, & Mickelson RS (2015). The patient work system: An analysis of self-care performance barriers among elderly heart failure patients and their informal caregivers. Applied Ergonomics, 47, 133–150. 10.1016/j.apergo.2014.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (2015). Families caring for an aging American. https://www.johnahartford.org/images/uploads/reports/Family_Caregiving_Report_National_Academy_of_Medicine_IOM.pdf

- International Family Nursing Association. (2015). IFNA Position Statement on Generalist Competencies for Family Nursing Practice. https://internationalfamilynursing.org/2015/07/31/ifna-position-statement-on-generalist-competencies-for-family-nursing-practice/

- International Family Nursing Association (IFNA). (2017). IFNA Position Statement on Advanced Practice Competencies for Family Nursing. https://internationalfamilynursing.org/2017/05/19/advanced-practice-competencies/

- Johnston BM, Milligan S, Foster C, & Kearney N (2012). Self-care and end of life care — patients’ and carers’ experience a qualitative study utilising serial triangulated interviews. Supportive Care in Cancer, 20(8), 1619–1627. 10.1007/s00520-011-1252-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2017). Serious illness in late life: The public’s views and experiences. https://www.kff.org/other/report/serious-illness-in-late-life-the-publics-views-and-experiences/

- Kanter C, Agostino NMD, Daniels M, Stone A, & Edelstein K (2014). Together and apart : Providing psychosocial support for patients and families living with brain tumors. Supportive Care in Cancer, 22(1), 43–52. 10.1007/s00520-013-1933-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keesing S, & Rosenwax L (2011). Is occupation missing from occupational therapy in palliative care? Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 58(5), 329–336. 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2011.00958.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutner JS, Kilbourn KM, Costernaro A, Lee CA, Nowels C, Vancura JL, Anderson D, & Keech TE (2009). Support needs of informal hospice caregivers: A qualitative study. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 12(12), 1337–1342. 10.1089/jpm.2009.0178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilly MB, Robinson CA, Holtzman S, & Bottorff JL (2011). Can we move beyond burden and burnout to support the health and wellness of family caregivers to persons with dementia? Evidence from British Columbia, Canada. Health & Social Care in the Community, 20(1), 103–112. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.01025.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo C, Ilic D, Teede H, Cass A, Fulcher G, Gallagher M, Kerr PG, Murphy K, Polkinghorne K, Russell G, Usherwood T, Walker R, & Zoungas S (2016). The perspectives of patients on health-care for co-morbid diabetes and chronic kidney disease: A qualitative study. PLOS ONE, 11(1), Article e0146615. 10.1371/journal.pone.0146615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockie SJ, Bottorff JL, Robinson CA, & Pesut B (2010). Experiences of rural family caregivers who assist with commuting for palliative care. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 42(1), 74–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Marcos M, & De la Cuesta-Benjumea C (2014). Women’s self-management of chronic illnesses in the context of caregiving: A grounded theory study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24(11–12), 1557–1566. 10.1111/jocn.12746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason B, Nanton V, Epiphaniou E, Murray SA, Donaldson A, Shipman C, Daveson BA, Harding R, Higginson IJ, Munday D, Barclay S, Dale J, Kendall M, Worth A, & Boyd K (2016). “My body’s falling apart.” Understanding the experiences of patients with advanced multimorbidity to improve care: Serial interviews with patients and carers. BMJ Supportive and Palliative Care, 6(1), 60–65. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters S, Oliver-Baxter J, Barton C, Summers M, Howard S, Roeger L, & Reed R (2013). Programmes to support chronic disease self-management: Should we be concerned about the impact on spouses? Health & Social Care in the Community, 21(3), 315–326. 10.1111/hsc.12020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman A, & the PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Asencio JM, Martin-Santos FJ, Kaknani S, Morilla-Herrera JC, Cuevas Fernández-Gallego M, García-Mayor S, León-Campos Á, & Morales-Gil IM (2014). Living with chronicity and complexity: Lessons for redesigning case management from patients’ life stories—A qualitative study. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 22(1), 122–132. 10.1111/jep.12300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiving. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S. 2015. https://www.caregiving.org/caregiving2015/

- Nguyen L, Keshavjee K, Archer N, Patterson C, Gwadry-Sridhar F, & Demers C (2017). Barriers to technology use among older heart failure individuals in managing their symptoms after hospital discharge. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 105, 136–142. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa CY, Buchanan Lunsford N, & Lee Smith J (2019). Impact of informal cancer caregiving across the cancer experience: A systematic literature review of quality of life. Palliative & Supportive Care, 18(2), 220–240. 10.1017/S1478951519000622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappa K, Doty T, Taff SD, Kniepmann K, & Foster ER (2017). Self-management program participation and social support in Parkinson’s disease: Mixed methods evaluation. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics, 35(2), 81–98. 10.1080/02703181.2017.1288673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paskett E, Thompson B, Ammerman AS, Ortega AN, Marsteller J, & Richardson D (2016). Multilevel interventions to address health disparities show promise in improving population health. Health Affairs, 35(8), 1429–1434. 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perzynski AT, Ramsey RK, Colón-Zimmermann K, Cage J, Welter E, & Sajatovic M (2017). Barriers and facilitators to epilepsy self-management for patients with physical and psychological co-morbidity. Chronic Illness, 13(3), 188–203. 10.1177/1742395316674540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retrum JH, Nowels CT, & Bekelman DB (2013). Patient and caregiver congruence: The importance of dyads in heart failure care. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 28(2), 129–136. 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3182435f27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard AA, & Shea K (2011). Delineation of self-care and associated concepts. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 43(3), 255–264. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2011.01404.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]