Abstract

Objective

To determine whether primary trabeculectomy or primary medical treatment produces better outcomes in term of quality of life, clinical effectiveness, and safety in patients presenting with advanced glaucoma.

Design

Pragmatic multicentre randomised controlled trial.

Setting

27 secondary care glaucoma departments in the UK.

Participants

453 adults presenting with newly diagnosed advanced open angle glaucoma in at least one eye (Hodapp classification) between 3 June 2014 and 31 May 2017.

Interventions

Mitomycin C augmented trabeculectomy (n=227) and escalating medical management with intraocular pressure reducing drops (n=226)

Main outcome measures

Primary outcome: vision specific quality of life measured with Visual Function Questionnaire-25 (VFQ-25) at 24 months. Secondary outcomes: general health status, glaucoma related quality of life, clinical effectiveness (intraocular pressure, visual field, visual acuity), and safety.

Results

At 24 months, the mean VFQ-25 scores in the trabeculectomy and medical arms were 85.4 (SD 13.8) and 84.5 (16.3), respectively (mean difference 1.06, 95% confidence interval −1.32 to 3.43; P=0.38). Mean intraocular pressure was 12.4 (SD 4.7) mm Hg for trabeculectomy and 15.1 (4.8) mm Hg for medical management (mean difference −2.8 (−3.8 to −1.7) mm Hg; P<0.001). Adverse events occurred in 88 (39%) patients in the trabeculectomy arm and 100 (44%) in the medical management arm (relative risk 0.88, 95% confidence interval 0.66 to 1.17; P=0.37). Serious side effects were rare.

Conclusion

Primary trabeculectomy had similar quality of life and safety outcomes and achieved a lower intraocular pressure compared with primary medication.

Trial registration

Health Technology Assessment (NIHR-HTA) Programme (project number: 12/35/38). ISRCTN registry: ISRCTN56878850.

Introduction

Glaucoma is a chronic progressive eye disease with substantial and detrimental effects on many aspects of daily living.1 It is the second most common cause of irreversible blindness in the UK, North America, and Europe.2 3 The number of patients with glaucoma is predicted to increase substantially as the result of an ageing population.4

Open angle glaucoma initially affects the peripheral vision. Severe visual field loss occurs in people with advanced open angle glaucoma, which encroaches on central vision and eventually reduces visual acuity. Severe restriction of the visual field reduces quality of life and increases the risk of falls and fractures.1 People with advanced open angle glaucoma in both eyes, even with good visual acuity, may be eligible for certification as severely sight impaired.

The primary risk factor for blindness due to glaucoma is advanced vision loss at presentation.5 In the UK, guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) suggest that patients presenting with advanced disease should be offered trabeculectomy as a primary intervention but cite poor evidence to support this recommendation.6 This guidance is generally not followed owing to concerns about potential sight threatening surgical complications and lack of evidence supporting primary surgery. Most patients are treated medically with escalating topical drug therapy,7 only undergoing trabeculectomy if medical management is not successful. In North America, no specific guidance exists for treatment of patients with advanced glaucoma at diagnosis.8 9 In Europe, guidance suggests that glaucoma surgery (trabeculectomy) can be offered.10 In the UK, 10-39% of patients with glaucoma present with advanced disease in at least one eye,11 12 with late presentation being associated with socioeconomic deprivation.11 13 14 The management of advanced glaucoma is associated with significant costs for healthcare systems.15

Effective treatment can control the disease, prevent further sight loss, and so prevent blindness. Reducing intraocular pressure is the only proven effective treatment for glaucoma.16 17 Better control of intraocular pressure at the initial stage following diagnosis reduces the risk of further progression.18

In a Cochrane systematic review comparing primary medical treatment and surgical treatment for open angle glaucoma, the authors concluded that trabeculectomy lowers intraocular pressure more than drugs do but also that previous trials excluded patients with advanced disease and did not reflect current medical and surgical practice.19 They identified comparison of current medical options and modern trabeculectomy in people with advanced open angle glaucoma as a research priority.19 The Public Health Outcomes Framework for England 2013-16 has also made reducing the number of people living with preventable sight loss a priority,20 and identifying the most effective treatment for glaucoma is a priority of the James Lind Alliance (https://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/priority-setting-partnerships/sight-loss-and-vision/top-10-priorities/glaucoma-top-10.htm).

We carried out a multicentre randomised controlled trial comparing primary medical management against primary trabeculectomy for people presenting with previously untreated advanced open angle glaucoma.

Methods

Trial design

The Treatment of Advanced Glaucoma Study (TAGS) was a pragmatic, multicentre, randomised unblinded controlled trial conducted in 27 centres in the UK. The trial design and baseline characteristics are available elsewhere.21 22 The trial protocol is available in supplementary appendix 1. The study was conducted in accordance with good clinical practice guidelines and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. An independent data and safety monitoring committee appraised adverse events and reported to an independent trial steering committee (supplementary appendix 2).

Participants

We recruited adults with newly diagnosed advanced glaucoma, defined according to the extent of visual field loss (Hodapp-Parrish-Anderson classification),23 in one or both eyes. The principal inclusion criterion was diagnosis of open angle glaucoma (including pigment dispersion glaucoma, pseudoexfoliative glaucoma, and normal tension glaucoma). We excluded patients who were unable to undergo incisional surgery or had a high risk of trabeculectomy failure. Supplementary table A provides a complete list of inclusion and exclusion criteria. All participants provided written informed consent before participation.

Randomisation and masking

We randomly assigned participants (1:1) to trabeculectomy or medical management, using a minimisation algorithm based on centre and bilaterality of disease. The unit of randomisation was the participant (not the eye). For participants in whom both eyes were eligible, we selected an index eye on the basis of less severe disease according to the mean deviation value of the visual field, but both eyes would receive the same allocated treatment. Randomisation used a remote web based application located at the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials (CHaRT; University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, UK). All participants were started on medical treatment at the time of diagnosis. After randomisation, participants allocated to trabeculectomy were placed on the surgical waiting list and continued medical treatment to lower their intraocular pressure until trabeculectomy was undertaken. We anticipated that surgery would occur within three months of randomisation.

Surgeons and participants could not be masked to the allocated procedure because of the nature of the interventions. Masking of intraocular pressure measurement was achieved through a two observer method.21 Visual field assessment was done by an independent reading centre masked to treatment allocation.

Trial interventions

We defined standard trabeculectomy as the fashioning of a “guarded fistula.” The surgeon created a small hole into the anterior chamber of the eye, covered by a flap of partial thickness sclera allowing aqueous humour to filter into the subconjunctival space. The exposure time and concentration of mitomycin C was left to the discretion of the operating surgeon and decided for each case. The operation could be performed under either local or general anaesthesia. Each operating surgeon was a fellowship trained glaucoma specialist who had done at least 30 augmented trabeculectomies. All potential surgeons completed a surgical technique questionnaire to ensure that the recognised standard trabeculectomy procedures were followed.24 25 The chief investigator reviewed and signed off these questionnaires. If trabeculectomy surgery failed to control intraocular pressure adequately, medical management was started to further lower the intraocular pressure.

Participants randomised to medical treatment underwent an escalating medical management regimen and were treated with a variety of licensed glaucoma drugs (eye drops) in accordance with NICE guidelines.6 Escalation of medical management was based on the judgment of the treating clinician. If drops failed to control intraocular pressure adequately, oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitors could be used. If control of intraocular pressure was deemed inadequate on maximum medical therapy, augmented trabeculectomy was offered. Guidance for target intraocular pressure setting was provided by the Canadian Glaucoma Society Target IOP workshop algorithm,26 which suggests an intraocular pressure of below 15 mm Hg for patients with advanced glaucoma. However, this was not proscriptive, and, in keeping with the pragmatic nature of the trial, the patient’s clinician determined the target intraocular pressure in each case.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was health related quality of life measured using the Visual Function Questionnaire-25 (VFQ-25) at 24 months.27 Secondary outcomes included patient reported outcomes: the EuroQol Group’s 5 dimension 5-level health status questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L),28 the Health Utility Index-mark 3 (HUI-3),29 the Glaucoma Utility Index (GUI),30 and the patient’s experience. For VFQ-25, the range of values is from 0 for the lowest visual quality of life to 100 for the highest visual quality of life. For the EQ-5D and HUI-3, a score of 0 is a state equivalent to death and 1 is full health. For the GUI, 0 is the worst state in terms of the effects of glaucoma and the side effects of treatments and 1 is the best possible state. The secondary clinical effectiveness outcomes were intraocular pressure, logarithm of mean angle of resolution (logMAR) visual acuity, visual field mean deviation measured with the Humphrey Visual Field Analyzer, need for cataract surgery, pass/fail of the visual standards for driving (based on the Esterman visual field), eligibility for sight impairment certification, and the safety of interventions. Adverse events were recorded by the local investigators and obtained through follow-up questionnaires completed by participants. We considered events related to participating in the trial or related to glaucoma to be adverse events. Supplementary table B lists the study outcomes and collection times. All ocular outcomes (visual acuity, visual field mean deviation, intraocular pressure, medications, need for cataract surgery) and ocular safety events are reported for the index eye.

Statistical analysis

We needed outcome data on 190 participants in each group for 90% power at a two sided 5% significance level to detect a difference in means of 0.33 of a standard deviation. This translated to a 6 point difference on the VFQ-25, assuming a common standard deviation of 18 points.31 We planned to randomise 440 patients to allow for a 13.5% (59/440) attrition rate. The study followed a pre-specified statistical analysis plan (supplementary appendix 3). Our analysis was based on the intention to treat (that is, analyse as randomised) principle. Statistical significance was at the two sided 5% level with corresponding confidence intervals derived. We used mean (SD) for continuous data and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables to summarise baseline and follow-up data. To analyse our primary outcome, we used a heteroscedastic partially nested repeated measures mixed effects linear model,32 correcting for baseline VFQ-25 and bilateral disease severity and including a random effect for surgeon by using restricted maximum likelihood. For missing baseline data, the centre specific mean was imputed. To estimate the treatment effect for adherence to allocated treatment, we used both per protocol analysis and complier average causal effect methods using instrumental variable regression.33 We analysed continuous secondary outcomes by using the same modelling approach. Intraocular pressure, logMAR visual acuity, and visual field mean deviation were analysed for the index eye. For GUI, we updated the scoring algorithm to reflect the characteristics of trial participants by using a discrete choice experiment administered as part of the TAGS study. For the patient’s experience, we used a repeated measure mixed effects Poisson model adjusting for bilateral disease and including a random effect for surgeon. For need for cataract surgery, visual standards for driving, and overall safety, we used a Poisson model adjusting for bilateral disease and including a random effect for surgeon to estimate relative risk. For adverse events and serious adverse events, we used a Poisson model adjusting for bilateral disease. For certification as sight impaired, we used Fisher’s exact test to compare groups. All estimates are presented with 95% confidence intervals. For the primary outcome, we did pre-specified subgroup analysis on variables shown in supplementary figure A, using a stricter level of statistical significance (two sided 1% significance level) and 99% confidence intervals. We used Stata version 16 software for all analyses.

Patient and public participation

We conducted a patient focus group exercise to inform willingness of patients to participate in the trial and to identify potential barriers to participation, the results of which we used to inform study design.34 Two lay members were involved in study oversight, one a glaucoma patient and the second a member of a glaucoma charity. One was a member of the Trial Steering Committee and the other a member of the Project Management Group. The lay members reviewed and approved all patient facing material for the trial, including the discrete choice experiment, before it was distributed to participants.

Results

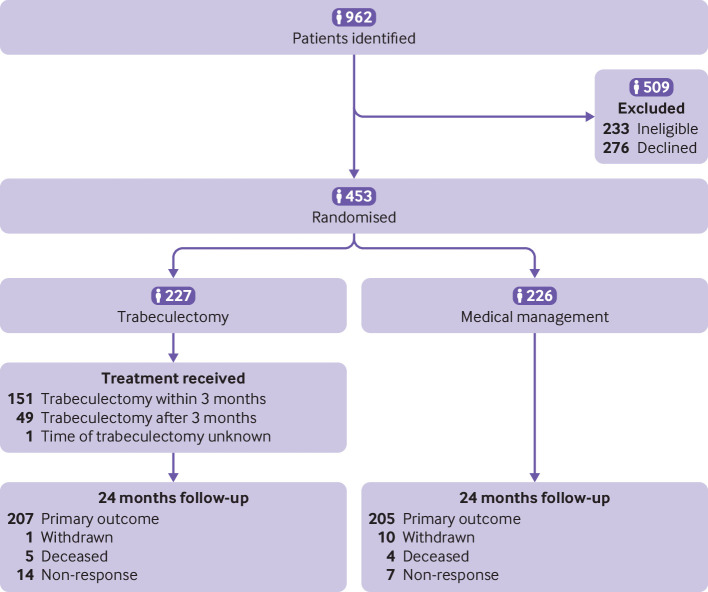

Between 3 June 2014 and 31 May 2017, 453 participants from 27 hospitals were allocated to either trabeculectomy (n=227) or medical management (n=226) (fig 1). In the trabeculectomy arm, 201/227 (89%) participants received trabeculectomy on their index eye. For the remaining 26 participants, four had surgery in their non-index eye, 16 declined surgery, two died before surgery, and four had yet to receive surgery. All participants in the medical management group received their allocated treatment, and 39/226 (17%) went on to receive trabeculectomy within two years.

Fig 1.

Trial consort diagram

For those recruited to the study, the mean age of participants was 67.6 (SD 12.3) years and 303/453 (67%) participants were male. For those who were eligible but declined to participate in the trial (n=276), the mean age was slightly higher at 69.6 (12.8) years (P=0.04) and 165 (60%) were male (P=0.17). The study arms were balanced at baseline (table 1). The mean VFQ-25 scores were 87.1 (SD 13.6) and 87.1 (13.4) in the trabeculectomy and medical management arms, respectively. Forty four participants in each arm had advanced glaucoma in both eyes.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Trabeculectomy (n=227) | Medical management (n=226) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age, years | 67 (12.2) | 68 (12.4) |

| Male sex | 156 (69) | 147 (65) |

| Ethnicity: | ||

| White | 182 (80) | 191 (85) |

| Afro-Caribbean | 32 (14) | 27 (12) |

| Asian—India/Pakistan/Bangladesh | 8 (4) | 4 (2) |

| Asian—Oriental | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Mixed heritage | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) |

| Other | 3 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) |

| Advanced glaucoma in both eyes | 44 (19) | 44 (19) |

| Glaucoma in both eyes | 178 (78) | 169 (75) |

| Eligible to be registered as sight impaired: | ||

| No | 214 (94) | 212 (94) |

| Sight impaired | 10 (4) | 12 (5) |

| Severely sight impaired | 3 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Glaucoma diagnosis: | ||

| Primary OAG (including NTG) | 219 (96) | 220 (97) |

| Pigment dispersion syndrome | 5 (2) | 4 (2) |

| Psuedoexfoliation syndrome | 3 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Diamox* | 6 (3) | 2 (1) |

| Family history of glaucoma: | ||

| Yes | 63 (28) | 79 (35) |

| No | 152 (67) | 131 (58) |

| Missing | 12 (5) | 16 (7) |

| Median (IQR) No of times visited optician in previous 10 years | 5 (2-6); n=214 | 5 (3-8); n=209 |

| Index of multiple deprivation: | ||

| 1st fifth (most deprived) | 54 (24) | 52 (23) |

| 2nd fifth | 30 (13) | 37 (16) |

| 3rd fifth | 45 (20) | 43 (19) |

| 4th fifth | 50 (22) | 43 (19) |

| 5th fifth (least deprived) | 47 (21) | 49 (22) |

| Missing | 1 (<1) | 2 (1) |

| Mean (SD) VFQ-25 score | 87.1 (13.6); n=226 | 87.1 (13.4); n=224 |

| Mean (SD) VFQ-25 subscale scores: | ||

| Near activities | 84.2 (18.5); n=225 | 84.4 (16.9); n=224 |

| Distance activities | 88.5 (16.1); n=226 | 89.7 (14.4); n=224 |

| Dependency | 94.0 (17.3); n=226 | 94.9 (15.7); n=222 |

| Driving | 85.9 (26.7); n=171 | 84.8 (26.2); n=158 |

| General health | 63.6 (23.4); n=225 | 60.9 (22.6); n=223 |

| Role difficulties | 87.1 (19.8); n=226 | 87.4 (20.8); n=222 |

| Mental health | 81.1 (21.2); n=226 | 81.8 (19.9); n=224 |

| General vision | 74.9 (14.5); n=223 | 72.8 (14.2); n=223 |

| Social function | 95.2 (11.9); n=225 | 94.9 (12.1); n=224 |

| Colour vision | 96.9 (10.9); n=223 | 96.6 (11.1); n=222 |

| Peripheral vision | 86.6 (20.8); n=224 | 87.2 (20.2); n=224 |

| Ocular pain | 84.7 (19.0); n=225 | 83.9 (17.2); n=224 |

| Mean (SD) EQ-5D-5L score | 0.844 (0.185); n=222 | 0.837 (0.176); n=222 |

| Mean (SD) HUI-3 score | 0.814 (0.202); n=214 | 0.809 (0.208); n=214 |

| Mean (SD) GUI score | 0.884 (0.131); n=219 | 0.863 (0.130); n=222 |

| Participant’s experience (glaucoma getting worse): | ||

| Yes | 95 (42) | 76 (34) |

| No | 113 (50) | 133 (59) |

| Missing | 19 (8) | 17 (8) |

| Visual standards for driving: | ||

| Pass | 187 (82) | 196 (87) |

| Fail | 27 (12) | 21 (9) |

| Missing | 13 (6) | 9 (4) |

| Mean (SD) VFMD for better eye, dB | −5.48 (6.37) | −5.49 (5.91); n=224 |

| Mean (SD) VFMD for worse eye, dB | −15.53 (6.88) | −15.89 (6.57) |

| Mean (SD) VFMD for non-index eye, dB | −6.1 (7.7) | −6.1 (7.1) |

| Baseline characteristics for index eye only | ||

| Lens status: | ||

| Phakic | 212 (93) | 209 (92) |

| Pseudophakic | 15 (7) | 17 (8) |

| Mean (SD) central corneal thickness, µm | 539.4 (35.7); n=226 | 541.4 (35.7); n=223 |

| Glaucoma drops: | ||

| Prostaglandin analogue | 186 (82) | 182 (81) |

| β blocker | 52 (23) | 52 (23) |

| Carbonic anhydrase inhibitor | 45 (20) | 33 (15) |

| α agonist | 7 (3) | 4 (2) |

| Diamox* | 6 (3) | 2 (1) |

| Ocular comorbidity | 50 (22) | 50 (22) |

| Ocular comorbidity details†: | ||

| Age related macular degeneration | 6 (12) | 4 (8) |

| Cataract | 42 (84) | 42 (84) |

| Vascular occlusion | 2 (4) | 1 (2) |

| Diabetic retinopathy | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Other | 9 (18) | 6 (12) |

| Mean (SD) VFMD, dB | −14.91 (6.36) | −15.26 (6.34) |

| Mean (SD) logMAR visual acuity | 0.15 (0.25) | 0.17 (0.26); n=223 |

| Mean (SD) intraocular pressure, mm Hg: | ||

| Diagnosis | 26.9 (9.1); n=226 | 25.9 (8.4); n=223 |

| Baseline | 19.4 (6.2); n=222 | 19.0 (5.7); n=221 |

EQ-5D-5L=EuroQol Group’s 5 dimension 5-level health status questionnaire; GUI=Glaucoma Utility Index; HUI-3=Health Utility Index-mark 3; IQR=interquartile range; logMAR=logarithm of mean angle of resolution; NTG=normal tension glaucoma; OAG=open angle glaucoma; VFMD=visual field mean deviation; VFQ-25=National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (25 items).

For VFQ-25, values range from 0 for lowest visual quality of life to 100 for highest visual quality of life. For EQ-5D and HUI-3, score of 0 is state equivalent to death and 1 is full health. For GUI, 0 is worst state in terms of effects of glaucoma and side effects of treatments and 1 is best possible state.

Taken orally.

Participants can have more than one.

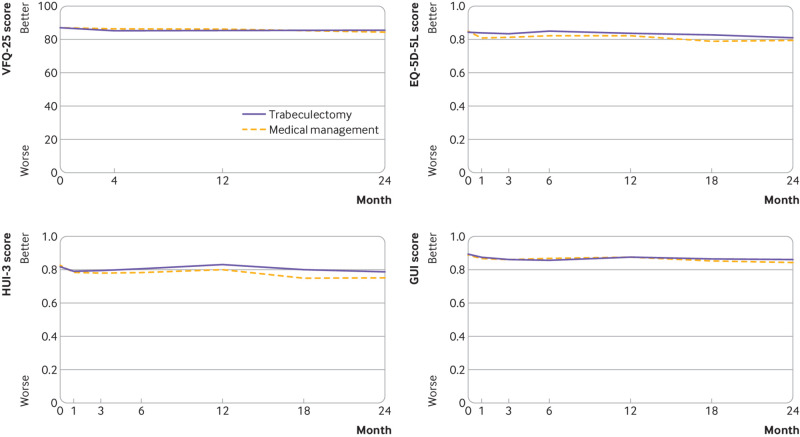

At 24 months, the mean VFQ-25 scores were 85.4 (13.8) and 84.5 (16.3) in the trabeculectomy and medical management arms, respectively. The mean difference was 1.06 (95% confidence interval −1.32 to 3.43; P=0.38) (table 2). The per protocol and complier average causal effect estimates for VFQ-25 were similar. We also found no evidence of any differences between the pre-specified subgroups (supplementary figure A) or for EQ-5D-5L, HUI-3, and GUI at 24 months (table 2; fig 2).

Table 2.

Primary and secondary outcomes. Values are mean (SD) unless stated otherwise

| Outcomes | Trabeculectomy (n=227) | Medical management (n=226) | Mean difference* (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VFQ-25: | ||||

| Baseline | 87.1 (13.6); n=226 | 87.1 (13.4); n=224 | - | - |

| 4 months | 85.1 (14.9); n=212 | 86.5 (13.6); n=216 | −1.24 (−3.58 to 1.11) | 0.30 |

| 12 months | 85.4 (14.3); n=214 | 86.3 (13.1); n=209 | −0.64 (−3.00 to 1.72) | 0.60 |

| 24 months | 85.4 (13.8); n=207 | 84.5 (16.3); n=205 | 1.06 (−1.32 to 3.43) | 0.383 |

| EQ-5D-5L: | ||||

| Baseline | 0.844 (0.185); n=222 | 0.837 (0.176); n=222 | - | - |

| 1 month | 0.838 (0.185); n=194 | 0.808 (0.203); n=203 | 0.025 (−0.012 to 0.062) | 0.19 |

| 3 months | 0.836 (0.167); n=186 | 0.814 (0.195); n=179 | 0.015 (−0.024 to 0.053) | 0.46 |

| 6 months | 0.850 (0.184); n=186 | 0.822 (0.204); n=195 | 0.016 (−0.021 to 0.054) | 0.39 |

| 12 months | 0.837 (0.177); n=211 | 0.823 (0.164); n=209 | 0.014 (−0.022 to 0.051) | 0.44 |

| 18 months | 0.828 (0.185); n=181 | 0.791 (0.219); n=184 | 0.023 (−0.016 to 0.061) | 0.24 |

| 24 months | 0.810 (0.179); n=206 | 0.796 (0.191); n=203 | 0.016 (−0.021 to 0.053) | 0.41 |

| HUI-3: | ||||

| Baseline | 0.814 (0.202); n=214 | 0.809 (0.208); n=214 | - | - |

| 1 month | 0.791 (0.232); n=184 | 0.786 (0.230); n=193 | −0.000 (−0.043 to 0.043) | 1.00 |

| 3 months | 0.796 (0.223); n=180 | 0.779 (0.222); n=179 | 0.007 (−0.036 to 0.051) | 0.74 |

| 6 months | 0.805 (0.216); n=180 | 0.782 (0.224); n=182 | 0.020 (−0.024 to 0.063) | 0.38 |

| 12 months | 0.829 (0.193); n=204 | 0.798 (0.199); n=196 | 0.024 (−0.018 to 0.066) | 0.26 |

| 18 months | 0.802 (0.212); n=169 | 0.749 (0.258); n=174 | 0.022 (−0.022 to 0.066) | 0.32 |

| 24 months | 0.786 (0.227); n=198 | 0.751 (0.246); n=193 | 0.036 (−0.006 to 0.078) | 0.09 |

| GUI: | ||||

| Baseline | 0.884 (0.131); n=219 | 0.863 (0.130); n=222 | - | - |

| 1 month | 0.862 (0.138); n=194 | 0.853 (0.156); n=205 | −0.000 (−0.028 to 0.028) | 0.98 |

| 3 months | 0.849 (0.130); n=187 | 0.844 (0.156); n=190 | −0.008 (−0.036 to 0.021) | 0.59 |

| 6 months | 0.839 (0.159); n=186 | 0.853 (0.135); n=191 | −0.024 (−0.052 to 0.005) | 0.11 |

| 12 months | 0.857 (0.139); n=209 | 0.860 (0.143); n=204 | −0.012 (−0.039 to 0.016) | 0.40 |

| 18 months | 0.851 (0.144); n=181 | 0.832 (0.157); n=184 | 0.003 (−0.026 to 0.032) | 0.83 |

| 24 months | 0.849 (0.152); n=205 | 0.830 (0.184); n=202 | 0.011 (−0.017 to 0.039) | 0.43 |

| Patient’s experience (glaucoma getting worse)—No (%): | ||||

| Baseline | 95/208 (46) | 76/209 (36) | - | - |

| 1 month | 60/188 (32) | 50/201 (25) | 1.19 (0.79 to 1.80) | 0.39 |

| 3 months | 37/182 (20) | 40/185 (22) | 0.88 (0.55 to 1.41) | 0.59 |

| 6 months | 30/182 (16) | 40/149 (20) | 0.74 (0.45 to 1.21) | 0.23 |

| 12 months | 38/207 (18) | 57/199 (29) | 0.59 (0.38 to 0.91) | 0.02 |

| 18 months | 40/180 (22) | 38/181 (21) | 0.99 (0.62 to 1.59) | 0.98 |

| 24 months | 44/196 (22) | 57/194 (29) | 0.70 (0.46 to 1.07) | 0.10 |

| Intraocular pressure, mm Hg†: | ||||

| Baseline | 19.4 (6.15); n=222 | 19.05 (5.73); n=221 | - | - |

| 4 months | 12.4 (5.73); n=217 | 16.40 (4.12); n=220 | −4.11 (−5.18 to −3.05) | <0.001 |

| 12 months | 11.9 (4.48); n=215 | 16.12 (4.54); n=209 | −4.25 (−5.33 to −3.18) | <0.001 |

| 24 months | 12.4 (4.71); n=206 | 15.07 (4.80); n=202 | −2.75 (−3.84 to −1.66) | <0.001 |

| LogMAR visual acuity†: | ||||

| Baseline | 0.15 (0.25); n=227 | 0.17 (0.26); n=223 | - | - |

| 4 months | 0.25 (0.31); n=210 | 0.16 (0.24); n=217 | 0.10 (0.05 to 0.14) | <0.001 |

| 12 months | 0.18 (0.23); n=212 | 0.16 (0.26); n=209 | 0.03 (−0.02 to 0.08) | 0.20 |

| 24 months | 0.21 (0.28); n=199 | 0.16 (0.26); n=201 | 0.07 (0.02 to 0.11) | 0.006 |

| Visual fields mean deviation, dB†: | ||||

| Baseline | −14.91 (6.36); n=227 | −15.26 (6.34); n=226 | - | - |

| 4 months | −14.35 (6.78); n=211 | −14.84 (6.52); n=217 | −0.05 (−0.79 to 0.70) | 0.907 |

| 12 months | −14.76 (6.92); n=214 | −14.95 (6.53); n=209 | 0.03 (−0.72 to 0.78) | 0.94 |

| 24 months | −15.15 (6.63); n=202 | −15.42 (6.39); n=200 | 0.18 (−0.58 to 0.94) | 0.65 |

| Need for cataract surgery—No (%) | 28/222 (13) | 27/221 (12) | 0.98 (0.50 to 1.95) | 0.96 |

| Visual standards for driving (pass/no defects)—No (%): | ||||

| Baseline | 187/214 (87) | 196/217 (90) | - | - |

| 24 months | 167/187 (89) | 168/188 (89) | 1.01 (0.81 to 1.25) | 0.95 |

| Registered as sight impaired at 24 months—No (%): | ||||

| No | 182/186 (98) | 184/184 (100) | - | 0.12 |

| Sight impaired | 4/186 (2) | 0/184 (0) | - | - |

EQ-5D-5L=EuroQol Group’s 5 dimension 5-level health status questionnaire; GUI=Glaucoma Utility Index; HUI-3=Health Utility Index-mark 3; logMAR; logarithm of mean angle of resolution; VFQ-25=National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (25 items); VFMD=visual field mean deviation.

For VFQ-25, values range from 0 for lowest visual quality of life to 100 for highest visual quality of life. For EQ-5D and HUI-3, score of 0 is state equivalent to death and 1 is full health. For GUI, 0 is worst state in terms of effects of glaucoma and side effects of treatments and 1 is best possible state.

Mean difference for continuous variables and risk ratios for dichotomous variables.

Index eye only.

Fig 2.

Mean National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (25 items) (VFQ-25), EuroQol Group’s 5 dimension 5-level health status questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L), Health Utility Index-mark 3 (HUI-3), and Glaucoma Utility Index (GUI) scores. For VFQ-25, range of values is from 0 for lowest visual quality of life to 100 for highest visual quality of life. For EQ-5D and HUI-3, score of 0 is state equivalent to death and 1 is full health. For GUI, 0 is worst state in terms of effects of glaucoma and side effects of treatments and 1 is best possible state

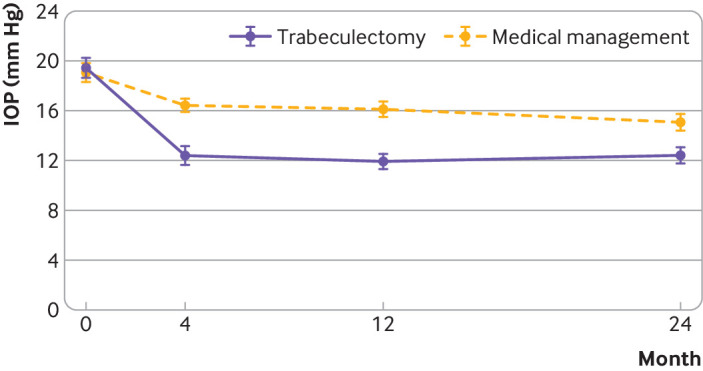

The mean intraocular pressure at 24 months was 12.4 (SD 4.7) mm Hg for the trabeculectomy arm and 15.1 (4.8) mm Hg for the medical management arm (mean difference −2.75 (95% confidence interval −3.84 to −1.66) mm Hg; P<0.001) (table 2; fig 3). The logMAR visual acuity was higher (worse) in the trabeculectomy arm (mean difference 0.07, 0.02 to 0.11; P=0.006) (table 2). We found no evidence of a difference in visual field mean deviation at 24 months (mean difference 0.18 (−0.58 to 0.94) dB; P=0.65) or other secondary outcomes (table 2).

Fig 3.

Mean (95% CI) intraocular pressure (IOP) for index eye by group over time

In total, 88/227 (39%) participants in the trabeculectomy arm and 100/226 (44%) in the medical management arm had a safety event during the 24 month follow-up (relative risk 0.88, 95% confidence interval 0.66 to 1.17; P=0.37) (table 3). Twelve (5%) of 227 participants in the trabeculectomy arm and 8/226 (4%) in the medical management arm had a serious adverse event (relative risk 1.50, 0.62 to 3.66; P=0.38). Eighty four (38%) of 222 participants in the trabeculectomy arm and 93/221 (42%) in the medical management arm had an adverse event (relative risk 0.90, 0.67 to 1.21; P=0.48). Nine deaths occurred, all unrelated to the trial. Two participants developed endophthalmitis, one in each arm of the study, and three lost more than 10 letters of logMAR visual acuity, all in the trabeculectomy group, two owing to progressive glaucoma and one owing to central serous retinopathy.

Table 3.

Safety events (index eye where ocular). Values are numbers (percentages)

| Events | Trabeculectomy (n=227) | Medical management (n=226) |

|---|---|---|

| No of participants with safety event | 88 (39) | 100 (44) |

| Serious adverse events | ||

| No of participants | 12/226 (5) | 8/226 (4) |

| No of events | 13 | 8 |

| Details: | ||

| Death | 5 | 4 |

| Life threatening | 0 | 1 |

| Hospital admission | 3 | 4 |

| Significant disability | 2 | 0 |

| Important condition | 3 | 1 |

| Expected event | 3 | 2 |

| Classification: | ||

| General medical (death) | 2 | 4 |

| Unclassified (death) | 3 | 0 |

| General medical | 2 | 3 |

| Related to glaucoma surgery | 3 | 1 |

| General ophthalmology | 1 | 0 |

| Non-glaucoma vision loss | 1 | 0 |

| Glaucoma progression despite treatment | 1 | 0 |

| Adverse events | ||

| No of participants | 84/222 (38) | 93/221 (42) |

| No of events | 139 | 155 |

| Details: | ||

| Drop related* | 18 | 83 |

| Ocular surface related† | 29 | 37 |

| Non-specific‡ | 19 | 17 |

| Early bleb leak | 12 | 3 |

| Hypotony (<6 mm Hg) requiring intervention | 11 | 3 |

| Choroidal effusion | 9 | 2 |

| Shallow anterior chamber | 7 | 2 |

| Ptosis | 5 | 1 |

| Hyphema | 4 | 0 |

| Late bleb leak | 4 | 0 |

| Potential adverse event related to surgery | 3 | 1 |

| Cataract | 1 | 2 |

| Conjunctival buttonhole | 3 | 0 |

| Corneal epithelial defect | 3 | 0 |

| Glaucoma progression | 1 | 2 |

| Irreversible loss of ≥10 ETDRS letters§ | 3 | 0 |

| Blebitis | 2 | 0 |

| Suprachoroidal haemorrhage | 2 | 0 |

| Endophthalmitis§—endogenous | 1 | 0 |

| Endophthalmitis§—bleb related | 0 | 1 |

| Persistent uveitis | 1 | 0 |

| Macular oedema | 0 | 1 |

| Non-specific unrelated uveitis | 1 | 0 |

ETDRS=Early Diabetic Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study.

Includes drop allergy, drop intolerance, periorbital skin pigmentation, taste disturbance.

Includes dry eye, blepharitis, meibomitis, corneal epitheliopathy, conjunctivitis, itchy eye, watering eyes.

Non-specific blurred vision, retinal vascular occlusion, vitreomacular traction, chalazion, subconjunctival haemorrhage.

Also recorded as a serious adverse event.

The need for additional interventions was greater in the trabeculectomy arm. All glaucoma surgery related serious adverse events (flat anterior chamber, ocular perforation during anaesthesia, diplopia, and bleb related endophthalmitis) needed further surgical intervention. Of the adverse events reported, 27 patients needed a further intervention to manage them, 24 in the trabeculectomy arm and three in the medical management arm. At 24 months, fewer participants were receiving topical drugs (53/211; 25%) in the trabeculectomy arm than in the medical management arm (163/208; 78%) (supplementary table C).

Discussion

At 24 months, we found no difference between treatment arms in the primary outcome, VFQ-25 score, which is an established method of assessing glaucoma related quality of life.35 36 This was also the case for other vision related and health related quality of life outcomes. Compared with baseline, surgery was more effective in lowering intraocular pressure at all time points measured, and the trabeculectomy arm required far fewer topical medications for control of intraocular pressure. Adverse events were similar between arms.

Comparison with other studies

For patients, maintaining their quality of life and independence is the most important outcome from their glaucoma management.37 38 Both eyes contribute to vision related quality of life, so this reflects the true visual experience of patients and reports the visual outcomes they achieve. The use of a patient reported outcome measure as the primary outcome reflects this importance and is consistent with the use of health related quality of life outcomes as primary outcomes in two previous recently published NIHR funded randomised controlled trials—Effectiveness in Angle Closure Glaucoma of Lens Extraction Study (EAGLE)39 and the Lasers in Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension Trial (LiGHT).40

We observed a clear reduction in intraocular pressure in both study arms for the duration of the study from similar baseline pressures. This was greater in the trabeculectomy arm, where we saw a reduction to 12.4 (SD 5.7) mm Hg at four months, and it remained at around 12 mm Hg for the remainder of the study. For the duration of the study, a 3-4 mm Hg additional reduction in intraocular pressure was achieved in the trabeculectomy arm. This is a clinically important difference likely to result in better preservation of visual field over a patient’s lifetime. A sustained reduction in intraocular pressure is recognised to be the most effective method of preventing further visual field loss in glaucoma.17 18 41

At 24 months, the modest deterioration in visual acuity is potentially due to the development of early cataract in the trabeculectomy arm42 43; although this was statistically significant, it may not be clinically significant as it corresponds to a reduction of only 2.5 letters of logMAR visual acuity,44 and quality of life and requirement for cataract surgery were very similar in both arms at 24 months. We found no substantive difference between arms for the other main measure of visual function and disease progression, the visual field test.

A major concern for clinicians was the perceived “high risk” of complications associated with trabeculectomy.7 The overall frequency of adverse events was broadly similar between the treatment arms. Two specific concerns of clinicians related to trabeculectomy were risk of blindness from bleb related endophthalmitis and risk of unexplained visual loss (“wipe-out”) immediately after surgery. No unexplained loss of vision occurred immediately after surgery, indicating no occurrence of wipe-out. The perceived risk of wipe-out is not supported by current evidence. Two patients developed endophthalmitis, one in each arm. One occurred in a participant originally allocated to the medical management arm who subsequently had a trabeculectomy for uncontrolled intraocular pressure. The other was an endogenous endophthalmitis related to a diabetic foot ulcer in a patient allocated to the trabeculectomy arm. Both were treated with intravitreal antibiotics and had good visual recovery.

All serious adverse events related to glaucoma surgery (flat anterior chamber, ocular perforation during anaesthesia, diplopia, and bleb related endophthalmitis) required further surgical intervention. Of the adverse events reported, 27 patients needed further intervention to manage them, 24 in the trabeculectomy arm and three in the medical management arm. All adverse events were managed successfully and no patients had any permanent vision loss associated with these adverse events. However, both clinicians and patients must be aware of the possibility of additional interventions being needed if the patient has trabeculectomy.

Strengths and limitations of study

We adopted a pragmatic approach to replicate current clinical practice in the management of advanced glaucoma as closely as possible. The inclusion of multiple centres and multiple surgeons undertaking standard trabeculectomy, along with the use of available topical medications, ensured that this study was representative of the current standard of care.6 8 9 10 Both of the interventions used in TAGS are used routinely worldwide to lower intraocular pressure.6 8 9 10 Potential participants in TAGS were excluded if they were deemed to be at high risk of trabeculectomy failure, as alternative surgical interventions are considered superior in these situations45; this is consistent with standard care in the UK. Large sample size, low attrition rate, involvement of multiple centres, the randomisation process, and masking for clinical assessments for intraocular pressure and visual fields minimised potential risk of bias.

Limitations include the fact that treatments and patient reported outcome measures could not be masked from participants or clinicians. Although the design of the trial was pragmatic, completion of questionnaires would not be part of standard care. This may have affected participants’ feeling of wellbeing either in a negative way owing to the burden of completion or in a positive way owing to the perception that they were being well cared for. However, no evidence exists of either a positive or negative effect. Rates of return and completion of questionnaires did not differ between study arms. In this study, most participants were white, which reflects the population of the UK; this may, however, limit the generalisability of our findings to non-white populations.

Conclusions

In conclusion, TAGS showed no difference in quality of life between treatment arms. Surgery was safe and achieved a sustained greater reduction in intraocular pressure compared with primary medication. This study provides the first direct evidence of the outcomes of interventions for patients presenting with advanced glaucoma. These results will inform clinicians and patients in making treatment choices.

What is already known on this topic

Advanced glaucoma at presentation is the biggest risk factor for lifetime blindness

Medical and surgical treatments for glaucoma are commonly used and effective at lowering intraocular pressure

Clinicians are reluctant to undertake primary surgery because of concerns about surgical complications and lack of evidence

What this study adds

Quality of life after intervention was equivalent between the treatments (trabeculectomy and medical treatment) for the period of the study

Trabeculectomy produced greater lowering of intraocular pressure than did medical treatment, and this was sustained

Severe vision loss as a consequence of trabeculectomy surgery did not occur

Acknowledgments

TAGS Study Group: Anthony King, Pavi Agrawal, Richard Stead; David C Broadway; Nick Strouthidis, Shenton Chew, Chelvin Sng, Marta Toth, Gus Gazzard, Ahmed Elkarmouty, Eleni Nikita, Giacinto Triolo, Soledad Aguilar-Munoa; Saurabh Goyal, Sheng Lim; Velota Sung, Imran Masood; Nicholas Wride, Amanjeet Sandhu, Elizabeth Hill; John Sparrow, Fiona Grey; Rupert Bourne, Gnanapragasam Nithyanandarajah, Catherine Willshire; Philip Bloom, Faisal Ahmed, Franesca Cordeiro, Laura Crawley, Eduardo Normando, Sally Ameen, Joanna Tryfinopoulou, Alistair Porteous, Gurjeet Jutley, Dimitrios Bessinis; James Kirwan, Shahiba Begum, Anastasios Sepetis, Edward Rule, Richard Thornton; Andrew McNaught, Nitin Anand; Anil Negi, Obaid Kousha; Marta Hovan; Roshini Sanders; Pankaj Kumar Agarwal, Andrew Tatham; Leon Au, Eleni Nikita, Cecelia Fenerty, Tanya Karaconji, Brett Drury, Duya Penmol; Ejaz Ansari, Albina Dardzhikova, Reza Moosavi, Richard Imonikhe, Prodromos Kontovourikis, Luke Membrey, Goncalo Almeida; James Tildsley; Augusto Azuara-Blanco, Angela Knox, Simon Rankin, Sara Wilson; Avinash Prabhu, Subhanjan Mukherji; Amit Datta, Alisdair Fern; Joanna Liput; Tim Manners, Josh Pilling; Clare Stemp, Karen Martin, Tracey Nixon; Caroline Cobb; Alan Rotchford, Sikander Sidiki; Atul Bansal, Obaid Kousha; Graham Auger, Mary Freeman.

Sponsor representative: Pauline Hyman-Taylor (from February 2019), Natalie McGregor (March 2015 to February 2019), Audrey Athlan (from July 2014 to March 2015), Joanne Thornhill (from 2013 to July 2014). Patient and public involvement representative: Rick Walsh, Russel Young. CHaRT Trial Office: Mark Forrest (from 2015), Gladys McPherson (until 2015). CHaRT Trial Office data coordinator: Pauline Garden. Health economists: Eoin Maloney (until 2015), Mehdi Javanbakht (until June 2019).

All participants in the trial, staff, and members of the TAGS Investigator Group responsible for recruitment in the clinical centres were as follows: Princess Alexandra Eye Pavilion, Edinburgh, NHS Lothian: Margaret McDonald, Margaret Frost, Angela James, June McGhie, Doreen Stewart, Laura Hughes; University Hospital, Coventry, University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust: Jeanette Allison, Margaret Dixon, Marie McCauley, Linzi Randle, Nigel Edwards, Kamaljeet Heer, Amritpal Chaggar, Vishal Thakrar, Suzanna Randen; St Thomas' Hospital, Guy's and St Thomas's NHS Foundation Trust: Stephanie Jones, Alba De Antonio, Andrew Ho, Elizabeth Galvis, Eme Chan, Jennifer Lee, Andrew Amon, Isabelle Chow; Hinchingbrooke Hospital, North West Anglia NHS Foundation Trust: Paula Turnbull, Jane Kean, Aarti Bahirat, Ivailo Zhekov, Chelsea Turnbull, Debra Jones, Aaron Woods, Linda Molloy; Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust: Mini David, Nicola Moss, Tomaz Jazwiecki, Maureen McMahon, Kim Green, Fawne Gibb, Lisa Haines, Rashedul Hoque, Jacqueline Denham, Madhu Mamman; Harrogate and District NHS Foundation Trust: Gillian Ranson, Debbie Wiggins, Caroline Clarke; The Royal Derby Hospital, Derby Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust: Sue Melbourne, Charlotte Downes, Ryan Humphries, Gill Widdowson, Lynsey Havill, John Sharp, Abbie Singleton, Tracy Brear, Howard Fairey, Aariana Sohal, Dorothy Gibson, Mona Mohamed; Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast Health and Social Care Trust: Rebecca Denham, Louise Scullion, Georgina Sterrett, Deirdre Burns, Lesley Doyle, Graham Young, Paul Wright, Vittorio Silvestri, Nuala Jane Lavery, Jonathan Keenan, Katie Graham; Norwich and Norfolk University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust: Heidi Cate, Sally Edmunds, Corinne Haynes, Karen Le Grys, Naomi Waller, Patricia Young; Manchester University, NHS Foundation Trust: Ian Venables; Kate Barugh, Monika Cien, Raisa Platt, Katie McGuiness, Stephanie Clarke, Daniel Todd, Patrick Gunn, Rosalind Creer, Leanne Richards, Catherine Park, Fatima Ahmed, Thomas Hamper, Deepali Bindal, Harriet Ndu-Melekwe, Martyn Russell, Tanya Karaconji, Brett Drury, Divya Permol; Bristol Eye Hospital, University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust: Beth Thorne, Emma Lamb, Ifan Jones, Jack Beange, Eleanor Hiscott, Jess Toole, Leila Cox, Julie Cloake, Clemence Rouquette, Gemma Bizley, Fran Paget, Carrie White, Gemma Brimson, Danielle Lee, Helen Talbot, Claire Buckland, Inderjit Chatha, Katherine Smith, Ketan Kapoor, Sebastian Howard; Sunderland Eye infirmary, City Hospitals Sunderland NHS Foundation Trust: Steve Dodds, Lauren Bell, Wenwei Woo, Jaswant Sandhu, Santy Nocon, Amanjeet Sandhu, Oliver Baylis, Ibrahim Masri, Karim El-Assal, Gemma Sloanes, Elizabeth Hill, David Lunt, Michelle Young, Shweta Singh, Sinead Connolly; Gloucestershire Eye Unit, Cheltenham General Hospital, Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust: Adrian Blazey, Anthony Burke, Frances Reilly; Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust: Helen Pokora, Maria Edwards, Martin Rhodes, Tom Evans, Jonathan Drury, Emily Henry; Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust: Patrick Cox, Lauren Tarr, Rebecca Nicol, Jade Higman, Zoe Bull, Laura Anderson, Renee Cammack, Jessica Kearsley, Athanasia Koumoukeli, Olivia Hay, Salina Saddiqui, Angela Skinner, Imran Jawaid, Alan Kastner, Amie Manjang, Francesco Stringa, Kostas Giannouladis; Queen Margaret Hospital, Dunfermline, NHS Fife: Karen Gray, Paul Allcoat, Julie Aitken, Ruth Robertson, Julie Donaldson, Sheila Hanlon; Warrington and Halton Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust: Mark Halliwell, Lynne Connell, Kerry Bunworth; Maidstone Hospital, Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust: Ruby Einosas, Susan Lord, Laura Reid, Stephanie Tidey, Audrey Perkins, Narkirst Bahra, Lynne Holmes, Sue Crockford, Karen O'Brien, Sara Harrison; Gartnavel General Hospital, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde: Aileen Campbell, Vicky Paterson, Geraldine Campbell, Fiona Mcintosh; Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust: Sophie Connor, Alexa King, Anar Shaikh, Dominic Carrington, Charles Amoah, Emerson Tingco, Jennette Elayba, Charlene Formento, Priya Dabasia, Soraya Al-Samarie, Kanom Bibi, Roel Cabellon, Christie Garcelales, Joel Real, Louis Wenigha, Martha Simango, Nafaz Illiyas, Elaina Reid, Paul Foster, Matt Kinsella, Edmore Ncube, Christine Fernandez, Hannah Williams, Evripidis Sykakis, Evangelia Gkaragkani, Roxanne Crosby-Nwaobi, Kirsty Chartier, Catherine Grigg, Panayiotis Panayiotou, Gaboitsiwe Maphango, Qin Neville, Anthony Khawaja, Karine Girard-Claudon, Nathan Kerr, Aberami Chandrakumar, Sash.Y Jeetun, Hamida Begum, Hannah Hounslow, Jasmeet Bahra, Hilary Swann, Katy Barnard, Gareth Davey, Cristina Citu, Ramona Berinde, Layla Juma, Jenny Elliot, Hayley Thomas, Tran Toan Dang, Shabneez Laulloo, Lucia Gonzalez, Minara Begum, Supeetha David, Hari Jayaram, Niraapha Sivakumaran, Tina Reetun, Sapna Shah, Diana Dabrickaite, Yusrah Shweikh, Priyansha Sheel, Ashish Mashru; Birmingham and Midland Eye Centre, Sandwell and West Birmingham Hospitals NHS Trust: Zain Juma, Richard Stead, Sue Southworth, Katie Atterbury, Esther Poole, Monica Hutton, Xicoli Chan, Patrick Chiam, Zoe Pilsworth, Risna Haq, Zahira Maqsood, Suaad Alasow, Melisa Fenton; Hairmyres Hospital, East Kilbride, NHS Lanarkshire: Anne McMurdo, Lesley Quigley, Elizabeth Shearer, Janice Simmons, Anne Moore, Karen Murray; Ninewells Hospital, Dundee, NHS Tayside: Heather Loftus, Michelle Robertson; York Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust: Srilakshmi Gollapothu, Alison Grice-Holt, Gillian Ranson, Gary Lamont, Sara Stringer, Carol Sarginson, Christine O'Dwyer, Joanne Wincup; James Paget University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust: Emma Stimpson, Lucy Hutchins, Tracy Duval, Lesley Parsons, Paula Head, Stephanie Cotton, Katie Riches, Amy Thanawalla, Katherine Mackintosh, Ellis Hinchley, Mya So; Imperial College Ophthalmology Research Group (ICORG), Western Eye Hospital, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust: Altaf Mamoojee, Zena Rodrigues, Eduardo Normando, Serge Miodragovic, Seham Jeylani, Paolo Bonetti, Jessica Bonetti; Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust: Carole Atkins, Clair Rea, Priyanka Divakar, Nicola Bennett, Sarita Jacob, Deepti Raina, Joseph Coombs, Farah Jabin.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Web appendix: Supplementary appendix 1 (TAGS protocol)

Web appendix: Supplementary appendix 2 (trial oversight)

Web appendix: Supplementary appendix 3 (statistical analysis plan)

Web appendix: Supplementary tables and figures

Contributors: AKing, JB, AA-B, JS, KB, DFG-H, JN, LV, and GM designed the study. AKing and GF managed the study with support, input, and oversight from JB, JH, AA-B, JS, KB, DFG-H, AM, JN, LV, and GM. JH, AKernohan, TH, and HS analysed the data, which were interpreted by all other authors. AKing wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which was reviewed, modified, and approved by all other authors. All the authors vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data reported and for the fidelity of the study to the protocol. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. AKing is the guarantor.

Funding: The project was funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Programme (project number 12/35/38). The Health Services Research Unit is funded by the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates. The funders had no role in considering the study design or in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the article for publication. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: support from the NIHR-HTA programme for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

The lead author affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: The dissemination plans include a final report to the NIHR-HTA programme (following peer review and editorial comments, the report is to be published as part of the NIHR Journal Series in Health Technology Assessment); working with NIHR-HTA to use its dissemination channels; presentation at the Royal College of Ophthalmologists Annual Congress, the largest UK meeting for ophthalmologists, and other national and international ophthalmological meetings; publications in open access peer reviewed journals; publications in popular practitioner journals (eg, Eye News, Health Services Journal); and work with Glaucoma UK, a glaucoma patients’ organisation, to communicate the findings to glaucoma patients through its website and social media communications. We have informed NICE of our results. The sponsor (Nottingham University Hospital) and Clinical Trials Unit (Aberdeen) will disseminate the results through their social media outlets (@ResearchNuh; @hsru_aberdeen). These will be further disseminated by the co-applicants’ social media outlets.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: TAGS Study Group, Anthony King, Pavi Agrawal, Richard Stead, David C Broadway, Nick Strouthidis, Shenton Chew, Chelvin Sng, Marta Toth, Gus Gazzard, Ahmed Elkarmouty, Eleni Nikita, Giacinto Triolo, Soledad Aguilar-Munoa, Saurabh Goyal, Sheng Lim, Velota Sung, Imran Masood, Nicholas Wride, Amanjeet Sandhu, Elizabeth Hill, John Sparrow, Fiona Grey, Rupert Bourne, Gnanapragasam Nithyanandarajah, Catherine Willshire, Philip Bloom, Faisal Ahmed, Franesca Cordeiro, Laura Crawley, Eduardo Normando, Sally Ameen, Joanna Tryfinopoulou, Alistair Porteous, Gurjeet Jutley, Dimitrios Bessinis, James Kirwan, Shahiba Begum, Anastasios Sepetis, Edward Rule, Richard Thornton, Andrew McNaught, Nitin Anand, Anil Negi, Obaid Kousha, Marta Hovan, Roshini Sanders, Pankaj Kumar Agarwal, Andrew Tatham, Leon Au, Cecelia Fenerty, Tanya Karaconji, Brett Drury, Duya Penmol, Ejaz Ansari, Albina Dardzhikova, Reza Moosavi, Richard Imonikhe, Prodromos Kontovourikis, Luke Membrey, Goncalo Almeida, James Tildsley, Augusto Azuara-Blanco, Angela Knox, Simon Rankin, Sara Wilson, Avinash Prabhu, Subhanjan Mukherji, Amit Datta, Alisdair Fern, Joanna Liput, Tim Manners, Josh Pilling, Clare Stemp, Karen Martin, Tracey Nixon, Caroline Cobb, Alan Rotchford, Sikander Sidiki, Atul Bansal, Obaid Kousha, Graham Auger, and Mary Freeman

Ethics statements

Ethical approval

Ethical approval: The trial protocol (supplementary appendix 1) was approved by the East Midlands – Derby Research Ethics Committee (reference number 13/EM/0395).

Data availability statement

Data sharing: Data will be available beginning 24 months and ending five years after publication of this paper. Data will be available for researchers who provide a methodologically sound scientific proposal, which has been approved by an ethics committee. Proof of the latter should be provided. Analyses should achieve the aims reported in the approved proposal. Requests for data sharing should be made to the corresponding author at anthony.king@nottingham.ac.uk.

References

- 1. Sotimehin AE, Ramulu PY. Measuring Disability in Glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2018;27:939-49. 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Flaxman SR, Bourne RRA, Resnikoff S, et al. Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study . Global causes of blindness and distance vision impairment 1990-2020: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e1221-34. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30393-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Quartilho A, Simkiss P, Zekite A, Xing W, Wormald R, Bunce C. Leading causes of certifiable visual loss in England and Wales during the year ending 31 March 2013. Eye (Lond) 2016;30:602-7. 10.1038/eye.2015.288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Royal College of Ophthalmologists. The Way Forward – Glaucoma. 2015. https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/RCOphth-The-Way-Forward-Glaucoma-300117.pdf.

- 5. Mokhles P, Schouten JS, Beckers HJ, Azuara-Blanco A, Tuulonen A, Webers CA. A Systematic Review of End-of-Life Visual Impairment in Open-Angle Glaucoma: An Epidemiological Autopsy. J Glaucoma 2016;25:623-8. 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institute of Health Care and Excellence. Glaucoma: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline [NG81]. 2017. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng81. [PubMed]

- 7. Stead R, Azuara-Blanco A, King AJ. Attitudes of consultant ophthalmologists in the UK to initial management of glaucoma patients presenting with severe visual field loss: a national survey. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2011;39:858-64. 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2011.02574.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Academy of Ophthalmology. Primary Open Angle Glaucoma: Preferred Practice Patterns. 2015. https://www.aaojournal.org/action/showPdf?pii=S0161-6420%2815%2901276-2.

- 9. Canadian Ophthalmological Society Glaucoma Clinical Practice Guideline Expert Committee . Canadian Ophthalmological Society evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for the management of glaucoma in the adult eye. Can J Ophthalmol 2009;44(Suppl 1):S7-93. 10.3129/i09.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. European Glaucoma Society . Terminology and Guidelines for Glaucoma. 4th ed. PubliComm, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ng WS, Agarwal PK, Sidiki S, McKay L, Townend J, Azuara-Blanco A. The effect of socio-economic deprivation on severity of glaucoma at presentation. Br J Ophthalmol 2010;94:85-7. 10.1136/bjo.2008.153312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boodhna T, Crabb DP. Disease severity in newly diagnosed glaucoma patients with visual field loss: trends from more than a decade of data. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2015;35:225-30. 10.1111/opo.12187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sukumar S, Spencer F, Fenerty C, Harper R, Henson D. The influence of socioeconomic and clinical factors upon the presenting visual field status of patients with glaucoma. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:1038-44. 10.1038/eye.2008.245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fraser S, Bunce C, Wormald R, Brunner E. Deprivation and late presentation of glaucoma: case-control study. BMJ 2001;322:639-43. 10.1136/bmj.322.7287.639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fiscella RG, Lee J, Davis EJ, Walt J. Cost of illness of glaucoma: a critical and systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics 2009;27:189-98. 10.2165/00019053-200927030-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Maier PC, Funk J, Schwarzer G, Antes G, Falck-Ytter YT. Treatment of ocular hypertension and open angle glaucoma: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2005;331:134. 10.1136/bmj.38506.594977.E0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Garway-Heath DF, Crabb DP, Bunce C, et al. Latanoprost for open-angle glaucoma (UKGTS): a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2015;385:1295-304. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62111-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. The AGIS Investigators . The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 7. The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration. Am J Ophthalmol 2000;130:429-40. 10.1016/S0002-9394(00)00538-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burr J, Azuara-Blanco A, Avenell A, Tuulonen A. Medical versus surgical interventions for open angle glaucoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(9):CD004399. 10.1002/14651858.CD004399.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Department of Health . Healthy Lives, Healthy People: Improving outcomes and supporting transparency. Department of Health, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21. King AJ, Fernie G, Azuara-Blanco A, et al. Treatment of Advanced Glaucoma Study: a multicentre randomised controlled trial comparing primary medical treatment with primary trabeculectomy for people with newly diagnosed advanced glaucoma-study protocol. Br J Ophthalmol 2018;102:922-8. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-310902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. King AJ, Hudson J, Fernie G, et al. TAGS Research Group . Baseline Characteristics of Participants in the Treatment of Advanced Glaucoma Study: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Ophthalmol 2020;213:186-94. 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hodapp E, Parrish RK, Anderson DR. Clinical decision in glaucoma. Mosby, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ergina PL, Cook JA, Blazeby JM, et al. Balliol Collaboration . Challenges in evaluating surgical innovation. Lancet 2009;374:1097-104. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61086-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McCulloch P, Altman DG, Campbell WB, et al. Balliol Collaboration . No surgical innovation without evaluation: the IDEAL recommendations. Lancet 2009;374:1105-12. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61116-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Damji KF, Behki R, Wang L, Target IOP Workshop participants . Canadian perspectives in glaucoma management: setting target intraocular pressure range. Can J Ophthalmol 2003;38:189-97. 10.1016/S0008-4182(03)80060-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mangione CM, Lee PP, Gutierrez PR, Spritzer K, Berry S, Hays RD, National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire Field Test Investigators . Development of the 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire. Arch Ophthalmol 2001;119:1050-8. 10.1001/archopht.119.7.1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011;20:1727-36. 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Furlong WJ, Feeny DH, Torrance GW, Barr RD. The Health Utilities Index (HUI) system for assessing health-related quality of life in clinical studies. Ann Med 2001;33:375-84. 10.3109/07853890109002092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burr JM, Kilonzo M, Vale L, Ryan M. Developing a preference-based Glaucoma Utility Index using a discrete choice experiment. Optom Vis Sci 2007;84:797-808. 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181339f30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Prior M, Ramsay CR, Burr JM, et al. Theoretical and empirical dimensions of the Aberdeen Glaucoma Questionnaire: a cross sectional survey and principal component analysis. BMC Ophthalmol 2013;13:72. 10.1186/1471-2415-13-72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Candlish J, Teare MD, Dimairo M, Flight L, Mandefield L, Walters SJ. Appropriate statistical methods for analysing partially nested randomised controlled trials with continuous outcomes: a simulation study. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18:105. 10.1186/s12874-018-0559-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Emsley R, Dunn G, White IR. Mediation and moderation of treatment effects in randomised controlled trials of complex interventions. Stat Methods Med Res 2010;19:237-70. 10.1177/0962280209105014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Leighton P, Lonsdale AJ, Tildsley J, King AJ. The willingness of patients presenting with advanced glaucoma to participate in a trial comparing primary medical vs primary surgical treatment. Eye (Lond) 2012;26:300-6. 10.1038/eye.2011.279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McKean-Cowdin R, Varma R, Wu J, Hays RD, Azen SP, Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Group . Severity of visual field loss and health-related quality of life. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;143:1013-23. 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McKean-Cowdin R, Wang Y, Wu J, Azen SP, Varma R, Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Group . Impact of visual field loss on health-related quality of life in glaucoma: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology 2008;115:941-948.e1. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.08.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bhargava JS, Patel B, Foss AJ, Avery AJ, King AJ. Views of glaucoma patients on aspects of their treatment: an assessment of patient preference by conjoint analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006;47:2885-8. 10.1167/iovs.05-1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kulkarni BB, Leighton P, King AJ. Exploring patients’ expectations and preferences of glaucoma surgery outcomes to facilitate healthcare delivery and inform future glaucoma research. Br J Ophthalmol 2019;103:1850-5. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-313401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Azuara-Blanco A, Burr J, Ramsay C, et al. EAGLE study group . Effectiveness of early lens extraction for the treatment of primary angle-closure glaucoma (EAGLE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016;388:1389-97. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30956-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gazzard G, Konstantakopoulou E, Garway-Heath D, et al. LiGHT Trial Study Group . Selective laser trabeculoplasty versus eye drops for first-line treatment of ocular hypertension and glaucoma (LiGHT): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2019;393:1505-16. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32213-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Heijl A, Leske MC, Bengtsson B, Hyman L, Bengtsson B, Hussein M, Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial Group . Reduction of intraocular pressure and glaucoma progression: results from the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120:1268-79. 10.1001/archopht.120.10.1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Patel HY, Danesh-Meyer HV. Incidence and management of cataract after glaucoma surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2013;24:15-20. 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32835ab55f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lichter PR, Musch DC, Gillespie BW, et al. CIGTS Study Group . Interim clinical outcomes in the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study comparing initial treatment randomized to medications or surgery. Ophthalmology 2001;108:1943-53. 10.1016/S0161-6420(01)00873-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gillespie BW, Musch DC, Niziol LM, Janz NK. Estimating minimally important differences for two vision-specific quality of life measures. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014;55:4206-12. 10.1167/iovs.13-13683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gedde SJ, Schiffman JC, Feuer WJ, Herndon LW, Brandt JD, Budenz DL, Tube versus Trabeculectomy Study Group . Treatment outcomes in the Tube Versus Trabeculectomy (TVT) study after five years of follow-up. Am J Ophthalmol 2012;153:789-803.e2. 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.10.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: Supplementary appendix 1 (TAGS protocol)

Web appendix: Supplementary appendix 2 (trial oversight)

Web appendix: Supplementary appendix 3 (statistical analysis plan)

Web appendix: Supplementary tables and figures

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing: Data will be available beginning 24 months and ending five years after publication of this paper. Data will be available for researchers who provide a methodologically sound scientific proposal, which has been approved by an ethics committee. Proof of the latter should be provided. Analyses should achieve the aims reported in the approved proposal. Requests for data sharing should be made to the corresponding author at anthony.king@nottingham.ac.uk.